You Higashino, 2009, Media Blasters

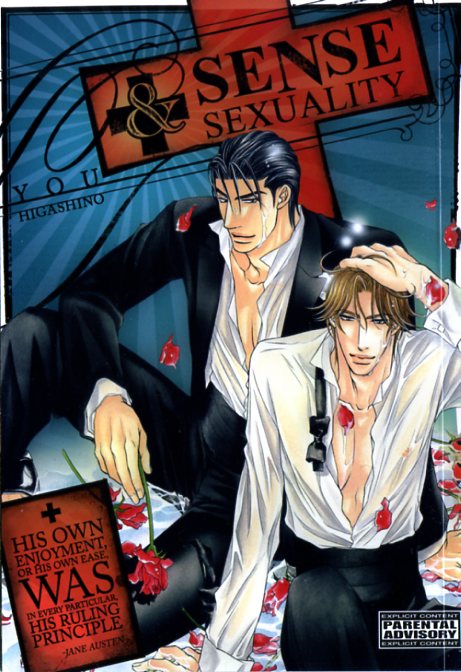

This manga was always going to be one of those things for me. Like when you’d really like a dense, perfectly moist brownie, but you go and get a bag of M&Ms from the snack machine instead. The experience isn’t without its redeeming features, but it isn’t the platonic chocolate experience whose reflection you once glimpsed against the wall of the cave in the flickering light of the bonfire. I was iffy about the plot description and a little less than iffy about the art. The cover design is quite good, and I’m pleased to see a bit of a trend toward actual design on these things, rather than just a big image of the characters embracing against a spray of flowers or whatever. They don’t have to look like 1970s romance novels. (Not that there’s anything wrong with that, but it’s nice to have options.) But I digress – as usual.

The plot synopsis advertises this as a Taisho era love story (and I originally typed “ploy synopsis,” which is a pretty insightful typo). The Taisho era was from 1912-1926, and I understand “Taisho jidai” means “the period of great righteousness,” which is an amusing setup for a decadent bit of porn. (I mean decadent in the Victorian/Edwardian aristocratic sense, as does Higashino. We’re not talking about cults of Cthulu. Although I’d love to read that. Oh my god.) The Taisho era was known for its liberalism, following the Mieji era, and this is also part of the joke – my knowledge of Japanese history is sadly fuzzy and lacking in details and context, but I’m almost certain that the liberalism of the day did not extend to a completely blasé attitude about same-sex cavorting. Please correct me if I’m wrong.

Higashino does, by the way, throw in an inexplicable (and clumsy) nod to historical accuracy by having one of our wealthy cad protagonists assaulted by communists. To which I said, huh. Communism was a big deal in Taisho Japan (and elsewhere). The Japanese communist party was founded in the early 20s in response to the Bolshevik victory in Russia a few years before, and there was high-profile violence. The police came down hard on the movement and had pretty much stamped it out at the end of the decade. Unlike the farmer and the cowman, communists and fabulously wealthy robber barons can’t really be friends. But throwing it into the middle of this mindless post-Edwardian romance just feels muddled. It’s a convenient plot device, certainly, and of course one must thrust one’s characters into each other’s arms in some way or other. But it felt heavy-handed, especially since the historical accuracy is otherwise, shall we say, uncertain. (And, oh dear, I feel another disclaimer is in order; I have nothing against historical inaccuracy, either. I’m all for it, in fact. It amuses me. What I’m commenting on here is the mix – juxtaposition is everything.)

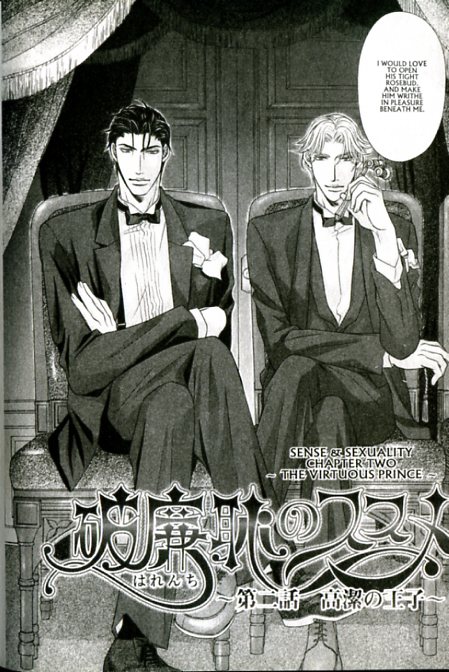

In the notes at the end of the manga, Higashino explains that the whole point of the manga was to draw dandies in the clothes of the time. That’s as good a reason as any, and better than some. And she does convey an aura of Oscar Wilde-ish world weariness and spoiled, bored dissolution and self-indulgence. So, full marks for that. The first stories of the book show a series of bets our two main characters make about who will be the first to seduce some sweet young thing. (The protagonists are named Masatsugu and Kuniomi, but we will refer to them as the blond and the brunet – or, ultimately, uke and seme, which should surprise no one. I have a hell of a time keeping track of some Japanese names because I am lame and undisciplined, and Masatsugu and Kuniomi flat-out refuse to stay in my brain for even a moment.) These are somewhat amusing and occasionally kind of charming. One of my favorite moments is when the blond looks out the window of his carriage at his next victim and says, “A school uniform, eh? It’s so stoic. It’s arousing.” At the beginning of another story/bet, he looks out from his box seat at the opera and says, “I would love to open his tight rosebud. And make him writhe with pleasure beneath me.” That’s funny stuff.

Also, there is actual nudity (instead of whited-out absences of genitalia or those bizarre half-there rods of light), and it is drawn reasonably well. After a series of these bets, the brunet confesses his constant and abiding love for the blonde and calls off any further bets. The blond is conflicted (which is to say, he does not say no to sex but is uncertain about the eternal love portion of the equation), but after the brunet is wounded by communists in an alley (“Your wealth was created by the suffering of the people! You’re going to pay!”), the blond starts to realize that he too has Serious Feelings. And they (literally) sail off into the sunset. It’s nice. It amused me and made me smile.

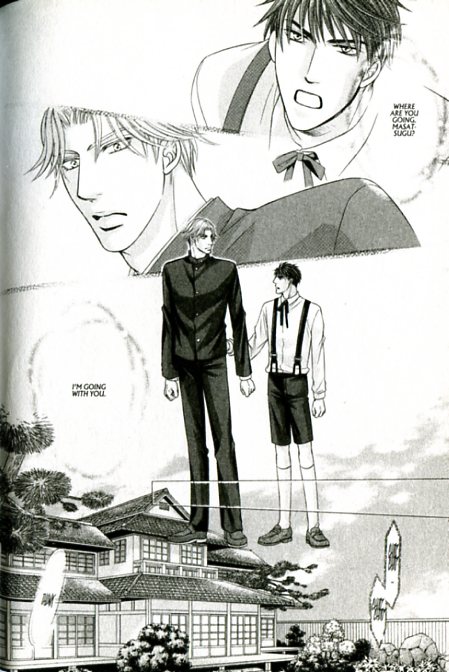

I do have an artistic bone to pick. The drawing is OK, overall, but there are a couple of clunkers that just made me stare in dismay. I mean, look at this:

What the hell? Seriously, what the hell? This is an abomination. (Maybe I should rethink my earlier enthusiasm for Elder God yaoi.) And while I’m flapping my hands in horror, I’ll note that there is the occasional blip in the sex scenes, too. Toward the end, brunet says to blond, “I’ll make love to you countless times, over and over… Until you smell like me from within.” To which I say – well, I don’t know what to say. Other than dear God, no.

These unfortunate malfunctions are the exception rather than the rule. They don’t ruin the reading experience, but they do leave a bad taste in your mouth. It’s the sort of thing I expected, though. I decided not to buy this title several times before I finally gave in, a victim to my completely irrational impulses. “It isn’t going to be that great, and you already have several thousand books in your to-read piles,” I said to myself. “But – but – but – post-Edwardian dandies! And I like the cover,” I whined back to myself. “You like all kinds of things. Things you’ve already purchased. Read one of those – this one isn’t going to be special.” “But – cover! Suits!” “Oh, for Christ’s sake, just go ahead and buy the damned thing, them.” “!!!!!! Cover! Suits!” Sigh. Sad, but true. I am a shallow magpie of a woman. So I bought it on July 18, according to Amazon’s handy feature that sometimes (but not always) keeps me from buying multiple copies of bright and shiny titles. Now that I have finally gotten around to reading it (which shows the level of anticipation I’d built up), I’m happy enough with it. I could like it more, but I could also like it a lot less. (I had a similar experience with Higashino’s Gay’s Anatomy, now that I think of it, except that I didn’t actually buy that one. It just came down to not really having a hospital fetish and also, inexplicably, not really liking characters in glasses.) (I assure you that Kinukitty has no such biases in real life.) (Thus endeth the pointless parenthetical comments and also, coincidentally, the post.)

Japan’s historical attitude toward male same-sex romance was more complex than you’d think. If you want to learn more, this book is an excellent place to start.

You know, Dirk, that is quite a coincidence, because that book is actually near the top of one of my to-read piles. I’ll move it closer to the front of the line.

Pingback: Fred Schodt, e-manga, and a movable feast « MangaBlog

If I recall correctly, Higashino is one of the few authors of mainstream yaoi who is openly male. Yaoi by men has sort of a bad reputation as explicit but not so solid on the story front, and I must say Higashino isn’t helping that stereotype.

And by the Taisho era Japan’s moralists were trying to stamp out the lingering traces of the shud? tradition. There were certainly still places where the well-informed gent could go to meet nice young men, but this book definitely overplays the general acceptability of such things.

Oh, that’s interesting, JRB, and thanks for the information. I shouldn’t just assume because yes, there certainly are men creating yaoi. It can be difficult to find out about them, though!