The growing affluence of the mainland Chinese has led to a steady growth in both the quantity and quality of reprints of classic Chinese comics. These comics have been available sporadically over the years but mostly in abridged and unlicensed versions. Even up to 10 years ago, the quality of these reprints were poor with images possibly 2-3 generations removed from the originals.

It is only in recent years that more expensive “collector’s editions” preserving the original format of the comics (i.e. a single image per page in rectangular booklets) have emerged.

The 2005 collector’s edition of Dream of the Red Chamber from the Shanghai Fine Arts Publishing House (SFAPH) is a case in point. The comics (lianhuanhua) from the SFAPH represent the high point of the adaptors art in China. Originating from the middle of the twentieth century their influence on all future adaptations of the four great novels of classical Chinese literature is inestimable.

As for the novel itself, a synopsis of this complex book can be found here and the full text is available here. The central story of Cao Xueqin’s tale concerns the tragic love affair between the two main protagonists, Lin Daiyu and Jia Baoyu, but the novel also charts the decline of an aristocratic family as viewed through the lens of a large cast of characters.

Perhaps the greatest difficulty faced by the adapters would have been condensing this lengthy novel into no more than 18 small booklets (one of which is pictured above). The Romance of the Three Kingdoms (which is of comparable length and apparently one of Mao Zedong’s favorite books) was given considerably more space in the form of some 60 booklets.

The narrative of Cao’s novel weaves and folds back on itself as it charts the progress of various secondary characters as they intersect with the members of the Rongguo household. At various points, the reader is made to feel the steady progression of time through the course of a day as relations are met, meals taken and courtesies exchanged. Hsia Chi Tsing calls this “the art of diurnal realism, the technique of advancing the novel with seemingly inconsequential accounts of day-to-day events…”, a technique which, Hsia suggests, Cao learnt from The Golden Lotus (or Jing Ping Mei; a famous work of classical Chinese literature known for its graphic sexuality).

This is a technique which is seldom used in comics if only because of the nature of the medium: its labour intensiveness, the spatial constraints it has had to contend with through much of its history and the intolerance of the market to such ventures.

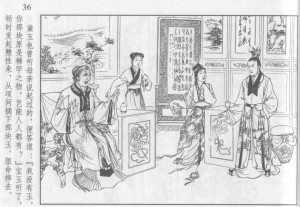

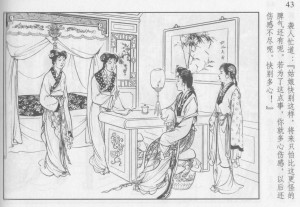

We find some aspects of this technique in the third chapter of Dream of the Red Chamber which follows the female protagonist, Lin Daiyu, over the course of a day through her introduction to various members of the Rongguo household. The pacing here is slow and deliberate with careful attention paid to the setting and decorum of the proceedings as well as the physical characteristics and personalities of Daiyu’s extended family.

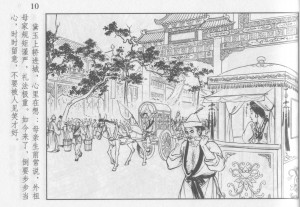

A truncated excerpt follows which begins with Daiyu’s arrival in the capital following her mother’s death. The English translation (with some alterations) is taken from the rather poor Canfonian edition of the comic:

[On the way to the capital, Daiyu thought, “Mother often said to me that grandmother-in-law is very strict. There are stringent family rules and etiquettes. Now that I am here I should be constantly on my guard and watch out in order not to be ridiculed.]

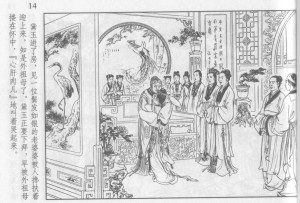

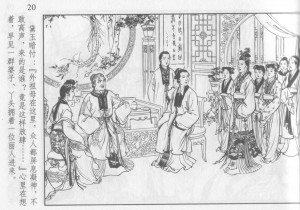

[When Daiyu entered the chamber she saw two maids holding a silver-haired old lady walking up to her. Daiyu knew she was her grandmother. As she was prepared to go on her knees to kowtow, her grandmother held her in her arms saying, “Dear heart! Flesh of my child!” and sobbed.]

A few moments later, Daiyu encounters her cousin, Xifeng for the first time: [Daiyu thought, “When grandmother is here all hold their breath, look attentive and remain silent. Who can this be? What rudeness.” As she was thinking, several old women and maids were seen accompanying a beautiful lady entering the chamber.]

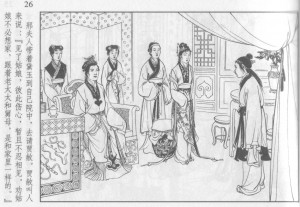

Daiyu meets the rest of the extended household. On this occasion she is brought by her aunt to meet her first uncle. From the novel: After a while the servant came back to report, “The master says he hasn’t been feeling too well the last few days, and meeting the young lady would only upset them both. He isn’t up to it for the time being. Miss Lin musn’t mope or be homesick here but feel at home with the old lady and her aunts…”

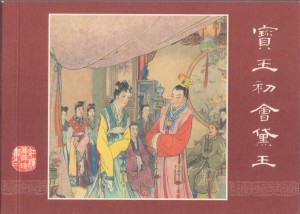

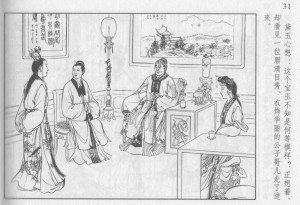

Daiyu meets Baoyu for the first time: [Daiyu mused, “What does Baoyu look like?” As she was thinking, a handsome well-dressed youngster was seen entering the room.]

[Daiyu replied, “I studied for one year. I know only a few characters.” Baoyu continued, “What’s your name, please?” Daiyu told him her name. Baoyu smiled and said to her, “Your eyebrows look half knit. “Pinpin” would be a most appropriate name for you.]

The conversation moves on to the piece of jade Baoyu was born with. [Daiyu once heard her late mother talk about this. She replied, “I don’t have any jade. Your jade is rare and precious. How could everybody have one like this?” On hearing this, Baoyu got into a rage. He took the jade from his neck and threw it hard on to the floor.]

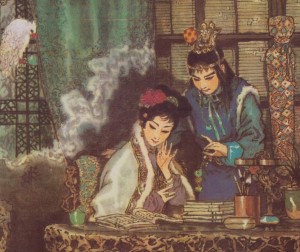

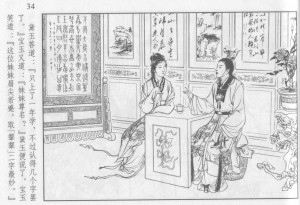

Daiyu discusses the day’s events with her maid later that night. [Xiren said, “Don’t be like that, Miss! In future, you will have to bear with his worst tempers. If you feel sad over this trifle, you’ll never have a moment’s peace. Don’t be so sensitive.”]

The comic adaptation irons out the twist and turns which make the novel so fascinating to the reader. It also excises a number of passages which serve to introduce the various members of the Rongguo household. The artist for this particular chapter of the adaptation rarely presents us with close-ups, preferring to observe the characters at a distance; respecting the rhythms of the original while paying careful attention to the dress of the characters, their facial expressions and surroundings – the delicate features of Daiyu, the attire and headdress of her lover, Baoyu, and the opulence of the Rongguo household.

It is an approach which is so different from the contemporaneous adaptation of The Romance of the Three Kingdoms, with its dramatic and shifting perspectives, that it suggests some sort of conscious choice on the part of the adapters. Everything which makes The Romance of the Three Kingdoms so readily adaptable – the colorful characters, the famous duels, the grand manoeuvres and strategies – are missing from Cao’s novel. It is a work which is perfectly suited to its original form.

Cao’s novel, with its languid pacing and extended conversations, is quite simply a comic adapter’s nightmare. One can easily see why cartoonist who seek to communicate extended periods of silent observation or mannered and largely uneventful (though not meaningless) dialogue often choose to enliven their works with more formal devices (Chris Ware’s Building Stories and Seth’s George Sprott being two notable North American examples from the last two years).

The SFAPH’s adaptation of Dream of the Red Chamber is also notable for leaving out the crucial first chapter in the novel where a Buddhist monk and Taoist priest come across a sentient stone discarded by the goddess Nü Wa following her repairs to the sky. This prologue not only explains the origins of the jade in Baoyu’s possession but also a number of the underlying themes of the novel. It is the very reason why Dream of the Red Chamber was once known as The Tale of the Stone. The SFAPH’s adaptation of The Romance of the Three Kingdoms is also notable for its omission of various supernatural interludes. A reader may be excused for suspecting an underlying agenda with respect to such decisions, especially in the light of the series’ preoccupation with fidelity and accuracy.

These flaws notwithstanding, this adaptation of Dream of the Red Chamber probably fulfills it primary purpose as a tool for the edification of the young or poorly educated. In assessing its overall vision and artistry, however, this comic series remains the poor cousin of the rest of the SFAPH’s adaptations of classical Chinese literature.

Pingback: Mostly reviews today « MangaBlog

I’m surprised as well by how many of the adaptations and simplifications leave out that prologue. I ran into the problem as a student trying to make sense of the book, since I’d started with an abridged version.

When we did our own annotated version (check it out: http://popupchinese.com/lessons/short-stories/dream-of-the-red-chamber) we left it in since it’s so critical to an understanding of the book.

I wonder if the reason for the decision was not in part that even native Chinese speakers find the original challenging these days. So maybe the decision was made to broaden the market appeal of the abridged version.

Pingback: A Classic Novel in Comic Form - Gamer Guide to Kung Fu