My first contact with the work of Ariel Schrag occurred almost ten years ago following the release of Potential from Slave Labor Graphics. My renewed interest in her work stems from my host’s, Noah Berlatsky’s, enthusiasm for her comics which he considers among the best produced this past decade.

Noah is probably Schrag’s most articulate apologists and I was especially interested in hearing his views on her work before I found a review he did for The Chicago Reader which neatly summarizes his affection for the book (it might be wise to read Noah’s review before continuing with this response to that piece of criticism):

” Written while Schrag was still an adolescent, Potential seems pitched more toward her peer group than the New York Times editorial board. It doesn’t have the purple rhetorical flourishes of Fun Home or the pomo magical realist tics of Maus. Its focus is the non-highbrow subject of teen-girl angst.”

The opening lines of Noah’s review encapsulate his disaffection for much of contemporary comics and fiction. It’s an aesthetic which favors a certain rawness, verisimilitude and directness over any form of perceived artifice. I don’t see this division as being particularly useful since I’ve found value in the comics produced by both schools.

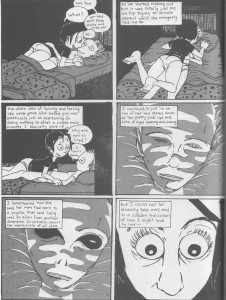

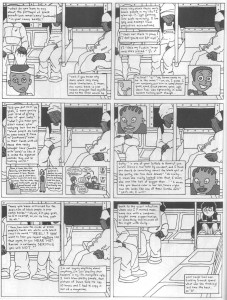

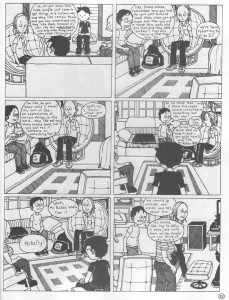

Schrag’s Potential contains journal-like reminiscences conveyed through her instinctive cartooning skills. The effect here is not unlike sitting in a room with the authoress herself. The plot in summary is simple: Ariel goes to high school, “discovers” that she is a lesbian, meets other girls and has occasional sex and alcohol.

The simplicity of the plot in itself is no hindrance to the creation of meaningful art. Rather, in the face of such a modest scenario, the reader expects to find pleasure in the details of the protagonist’s experiences and her emotional journey.

There are a few instances of success in this regard. The casual revelation over the course of a few pages that a bisexual girl with strong lesbian tendencies would want to have sex with a boy in order not to be considered a virgin is certainly unusual in gay and lesbian-themed comics, as is the sequence where Schrag looks down on Sally envisioning her as an alien. (Noah addresses a number of these issues in his almost Bonapartian analysis of Likewise)

Yet these moments of revelatory depth are infrequent and I often found myself faced with a broad swathe of unfiltered and largely undigested memories – a function of the diaristic roots of this comic.

One of the risks associated with adopting a certain naiveté in presentation is that it exposes the underlying content. A story may be “real” but this does not prevent it from being boring. Potential conforms to all the stereotypes we have come to expect from comics autobiography since the explosion of this form during the early 90s: it is periodically narcissistic and has much to tell us about sexual intercourse and masturbation.

Potential assembles various tepid high points in a high schooler’s life which are so banal (and I mean this in word all its fullness for I found little here which was emotionally moving or disturbing) in their disclosure that I literally had difficulty concentrating on the comic from panel to panel. Noah would say in Schrag’s defense that this betrays a lack of interest on my (or other like- minded reader’s) part in the life and thoughts of teenage girls. I would suggest rather that it betrays a lack of interest in the life of just any teenage girl. In the same way that not all autobiographies are worth reading, not every teenage journal is worthy of our attention or approbation.

The jumbled narrative of Schrag’s Potential has much to do with the messiness of life and resolves towards the closing pages of the book. Its authenticity lies in its complete formlessness, the primary structure here being that of linear time. Noah explains it thus in his review:

“Potential‘s open structure can make it seem unserious and unfocused, and, indeed, its opening pages aren’t especially emotionally fraught. It starts off as semi-comic teen melodrama…Schrag’s drawing skills have improved by leaps and bounds since her first comic, Awkward, but her figures remain fairly crude, and her layouts are messy. Still, she uses what she’s got, shifting her style to fit the emotional content.”

“Though there’s clearly a lot to be freaked out about, Schrag manages to present it with remarkable, almost clinical balance. She doesn’t use a nostalgic narrative voice to frame the events (like Bechdel’s in Fun Home), so she avoids the kinds of judgment and self-pity that often define memoir.”

Where Berlatsky sees sublime confusion, I see only a poorly edited journal. I much prefer the artist who prunes and refines a piece to one who rattles on however authentically. Quite simply put, these are comics which contain little in the way of beauty of form or language.

Contrary to Noah’s suggestions in his review, the semblance of a pure, unadulterated narrative are not the inviolable keys to success in the area of autobiography. Far better to acknowledge that all autobiography is adulterated because of their singular points of view. The judgements in Schrag’s comics are made more surreptitiously through the actions of the author and protagonist. And there are judgements aplenty in Potential as well as self-pity if only because these feelings form the fabric of our lives; they are inescapable.

Noah states at the start of his review that:

“…the things that make comics memoirs attractive to the literary establishment are the very things that make me itch. The self-conscious embrace of a weighty theme (mass slaughter, Iranian theocracy, what have you), the self-conscious distancing of writer-as-writer from writer-as-actor, the self-conscious and pervasive nostalgia—it all seems unbearably smug and earnest and plodding.” [bolds mine]

For those who have somehow managed to avoid reading Noah’s Chicago Reader review, I should add here that he is probably referring to Art Spiegelman’s Maus and Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis in this excerpt.

Schrag’s comics do contain “weighty” and time honored themes but ones so well mined that entry level perceptions and craft (and this is really all we get in Potential) no longer hold much sway in most readers’ minds. For all its artificiality and severity, Jafar Panahi’s The Circle remains more pressing and moving than anything in Schrag’s comics. The same may equally be said of Forugh Farrokhzad’s The House is Black. Both of these films may be set in the somewhat “alien” worlds of pre-revolutionary and theocratic Iran but their strengths emanate from uncommon revelation and perspicacious depictions of human suffering, injustice and resilience.

Those acts of “distancing” (to use Noah’s phrase, though not solely limited to the terms he expresses in his review) allow for that exquisite and stimulating act of communication across all nationalities and age groups. Those elements of gentle artifice can turn that which is solitary and prosaic into something more relevant and immediate.

The blunt stream of consciousness writing which emerges in parts of Likewise (which is itself punctuated by some literary self-criticism and self-conscious remarks to the reader) appear to be tiny footsteps in this direction. They suggest a writer who is still learning her craft if only gradually.

Rob Clough has the following to say about these new explorations:

“There are so many conflicting artistic agendas in this book that one almost needs a scorecard. Part of this is due to the way Schrag was cycling through her influences so quickly. She started reading James Joyce’s ULYSSES as a senior and suddenly her work took on the time-fractured, stream-of-consciousness nature of Joyce’s fiction. At the same time, LIKEWISE has a decidedly postmodern bent, with Schrag pulling away from the narrative to make metatextual comments.”

Yet the efforts here are clumsy and poorly placed amidst the naturalistic framework of Schrag’s main narrative. It is one thing to wear your influences on your sleeve, quite another to assimilate them seamlessly into your work. While Noah may find Bechdel unbearably nostalgic and “purple” in Fun Home, there can be little doubt that she was far more successful at lining her comic with Proustian mechanics than Schrag was with Joyce.

In his recent review for The Hooded Utilitarian, Noah castigates Kristian Williams for his patronizing attitude towards Schrag in his review for Verbicide:

“But the recognition, on the one hand, of the successful fusing of form and content, the refusal to figure out why you find that fusion alienating, and the conclusion that the alienation has something to do with the fact that a high school girl has gotten too big for her britches — to me that all seems profoundly condescending. Williams would rather dismiss the book altogether than treat a high-school girl as a potential equal — someone who could, and in fact did, write a book that is too highbrow for his tastes.”

I disagree with Williams on Likewise vis-a-vis Potential (the former book is clearly superior) but this comment smacks of a bit of critical superciliousness. While Williams does fail to give heed to any possibility of narrative coherence in Likewise (at least in this review), his comments also work at a more elementary level as evidenced by the first two sentences of the following excerpt:

“The writing is similarly uneven, marred by long stretches of unstructured, unedited stream-of-conscious tediousness. This is bad enough at the level of a sentence, much less a chapter. But the overall narrative strategy of the book seems to have been assembled according to the same plan. The story starts at the beginning of senior year, and it ends just after graduation, but in between it becomes completely unmoored from linear time. It shifts backward and forward within the year, and back to previous years, and between narrative levels, and it does this so frequently, and so arbitrarily, that it becomes exceedingly difficult to place the events with any certainty in their proper sequence. Without time, causation and character development become impossibilities as well.”

Those two sentences suggest rather impatience with a poor regurgitation of techniques originating nearly a century ago. These qualitative judgments may be subjective to a certain extent but they are far from condescending. Noah see these sequences as essentially parodic but I also sense a more earnest attempt at experimenting with modernist techniques in sequential art. If Williams does not mention the various narrative forms in Likewise (the varied lettering and lines as well as the use of “computers” and “recordings” to tell the story), it may be that they do not seem quite so inspired to him in the light of current developments in contemporary comics.

Schrag is certainly apprised of what I’ll call here the sheer “lucidity” of the comics form (see her interview with Noah at Bitch Media). Techniques which may seem bewildering in other visual forms become almost obvious if reproduced in comics. Schrag suggests that this rests on the ability of pictures to “ground” the reader (a simplification since there are other attendant implications). This remains a double-edged sword and once led Leo John de Frietas to remark to Dave McKean (and once could easily disagree here) that comics are “just not subtle enough” to make “certain explorations of life.”

Over the past few decades, some artists have adhered splendidly to simplicity of form while others have been in a continual search for that creative frisson found at the other extreme of comics narrative. The latter group includes artist like Richard McGuire (“Here”), Seth, Chris Ware and Gilbert Hernandez (probably the cartoonist who has used sudden and unannounced shifts in time and space with the most abandon in contemporary comics). Schrag herself freely admits to taking a bit of inspiration from Spigelman’s Maus, in particular the comic within a comic found therein. Beyond the stimulating mechanics, however, lies the question of whether the work at hand coheres (both emotionally and intellectually) and begins to speak to something far deeper; whether its moves beyond a mere tickling of the synapses into our souls.

In many ways, much of the charm of Schrag’s work bears some relation to a sequence from page 25 of Likewise, a long sequence (self-mocking in tone) on the subject of having “It”:

“Ok, so you know some people just seem to get things in a certain way and they like certain things and you can understand why they like them, because it’s just like this understanding and only some things and some people like, recognize it…like those shoes remember how you told me you just kind of liked them when you got them but then you put in those thin laces and you realized they were perfect? That was realizing that they had It.”

Many of the arguments in favor of Potential rely on this “It” factor; that joy of recognition, that intangible spark of attraction.

Even highly individual works have the capacity to appeal to certain sections of society. Potential speaks distinctly and eloquently to the milieu being depicted within its pages as well as those who feel that almost inexplicable “connection”. Works like these make little effort to draw in readers beyond their narrow confines. This is both one of their deepest strengths and greatest weaknesses.

For those left unmoved by Schrag’s narrative, the text remains of passing interest as personal history, social anthropology and as evidence of the growth of a young writer on her way to better things. Time will tell but I have my doubts if this will be a work which most will look back with reverence and affection in the coming decades.

ADDENDA:

While Noah’s review of Potential for The Chicago Reader may have disappointed me as a piece of critical advocacy, his latest analysis of Likewise is exactly what I wanted from this roundtable. It grasps the text with both hands and makes speculative leaps which are a mix of the plausible to wildly subjective (like his description of Schrag’s charcoal drawing of “Joyce’s penis” as perhaps the most beautiful image in the book). I still consider Schrag a far better writer than she is an artist but this full blooded obsession with penises, creativity, gender identity and envy is absolutely Noah’s fiefdom in the small country that is comics criticism.

_____________

Update by Noah: My response to Suat’s post is here.

The entire Likewise Roundtable is here.

I will shortly post a response explaining why you are wrong about everything, Suat….but I did want to clarify one thing from your addenda. It’s true that the characterization of the charcoal penis as the loveliest image in the book is wildly subjective…but it’s not necessarily my subjective. I was trying (and completely failing) to note that it fits into an accomplished fine-art paradigm in a way that most of the other work in the book does not. I think this was clearer in an earlier draft…but oh well.

My personal favorite drawings are probably the sketchiest ones — which have a somewhat different fine art cred.

Pingback: Am I a Condescending Sexist Jerk? also: comics reviews and porn (February 2010) « Kristian Williams