1. Love

I remember, if somewhat hazily, the day my mother bought me my first art book. It was late morning after Sunday School in the early 80s and the location was the large basement outlet of a local book retailer which specialized in Chinese language books. The book cost her 50 Singapore dollars which would have been the equivalent of just over USD$30 at the time. I have no idea what prompted this indulgence since, till this day, she has little interest in art of that nature.

The tome in question was Pierre Gassier and Juliet Wilson’s The Life and Complete Works of Francisco Goya, and I was about 12. This was the first catalogue raisonné I ever owned and one of the few that I have read from cover to cover.

The ridiculously romantic ideas it conjured up in my mind proved quite deadly. I emerged from my first artist monograph with the wholly innocent and idealistic expectation that the artist was ever changing and ever learning; at one with the material, social and spiritual aspects of painting; and able to shift effortlessly between the needs of commerce and art. While I recognize these notions as so much foolishness today, I haven’t completely discarded all this childish baggage which still hangs about my neck like a millstone or some unkillable gene.

I’m still searching for that sense of astonishment when I first glanced at a plate from The Disasters of War or one of the Black Paintings, a sensation so strong that it could not even be matched by physically being in their presence 20 years later in the halls of the Prado. I’ve rediscovered that excitement at various points in my life: reading Gene Wolfe’s The Book of the New Sun; seeing my first film by Tarkovsky; being mesmerized by Mahler’s Second Symphony; and watching my first live opera (Berlioz’s The Trojans).

The comics which I read from day to day and from year to year almost never reach that far into my soul — the price one has to pay for being fully engaged and respectful of an artform which is still very much in its adolescence if not infancy. And because I still spend time every so often writing about comics, I do sometimes envy writers who can take a comic so fully to heart and translate this rapture into words; that long sought for and intangible flood of raw emotions imposing themselves on the mind as to create a moment of mute and incomprehensible admiration. These feelings, I suspect, derive primarily from instinct and are the product of experience rather than any formal education (though this necessarily ameliorates any such passions).

I will never be able to experience that same epiphany as Tim Krieder in his review of Al Columbia’s Pim and Francie or Chris Ware in his introduction to Jeffrey Moriarity’s Jack Survives. It is altogether likely that I would remain stubbornly ignorant and insensitive even if if Kreider or Ware sat down beside me and pointed out precisely what they enjoyed about these comics, blind to the treasures before me. Yet what I appreciate about such articles is how they reach very specifically and wholeheartedly into areas which are indefinable and untestable. They are not so much about conveying the writer’s intellectual engagement (though there is some of that) but some deep emotional connection, a moment of profound, unfiltered ecstasy.

One might say that what I’m looking for is akin to that first flush of romantic love, that head over heels feeling which is often deemed facile but which is altogether precious; a transformative phase which can evolve into something more sustainable, committed, and deep. Now it may be that the emotions experienced in the latter phase may be privileged over the former in most societies. Certainly as many fruitful and long lasting relationships have blossomed from a slow burning affection as from more phosphorescent flashes. It must be said though that I, like most people, would prefer to experience both these emotions in encountering a life partner. It is only with the passage of years that we would be able to ascertain if we had attained that latter stage and its accompanying emotions.

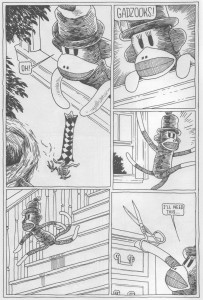

2. The Monkey (Sock Monkey Vol. 3 No. 2. )

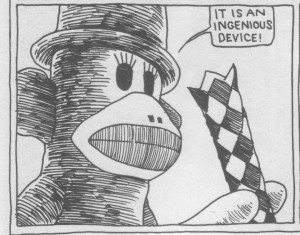

The Chinese handcuff or finger-trap is a tubular construct which entraps a person’s finger upon elongation of its stems. It is a toy of American origin, as is the Sock Monkey of Tony Millionaire’s tale.

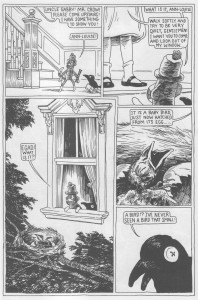

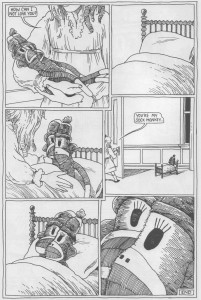

The monkey’s owner is a girl named Anne-Louise and on page 3 of Millionaire’s short story she advises the monkey and his companion that she has something very interesting for them to look at upstairs.

It turns out to be a baby bird, just born and perhaps blind, clearly visible from the second storey window of the large Victorian house the toys reside in.

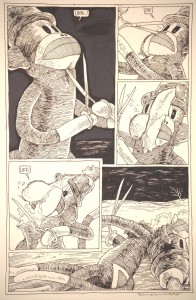

The toys are strictly advised not to touch the baby bird but the monkey decides that the distance afforded by the aforementioned device will circumvent any censure. He deploys it to disastrous effect, and the bird is rudely plucked from its place of sanctuary.

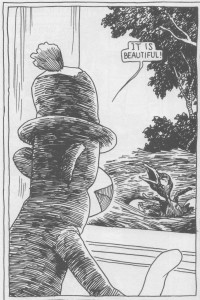

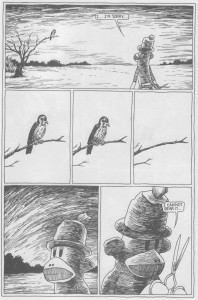

When the monkey races down to assess the condition of his new friend, his first reaction is that of utter silence.

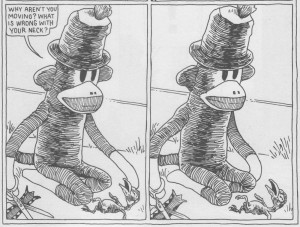

The monkey’s face is mysterious in its lack of expression, his sense of despair captured by his sudden diminution and isolation on the page where once he filled each inhabited panel.

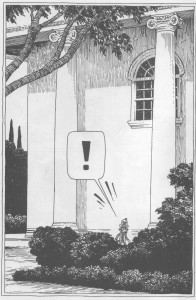

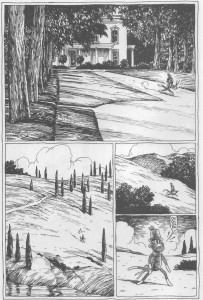

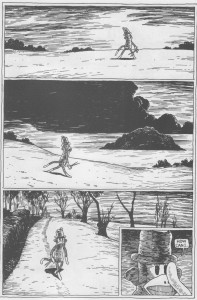

We see his tiny figure in an increasingly bleak landscape of dark clouds, withering trees and cypress; always moving towards the right edge of each panel, as if the artist was having trouble keeping up with his escape.

He comes to rest slowly and despondently in a wasteland far removed from the comforts of Anne-Louise’s bedroom. There is the stuttering apology to a mute and anonymous bird that may or may not be the dead bird’s mother; an unanswered plea for some ill-defined forgiveness…

…a futile act of carnage [1]…

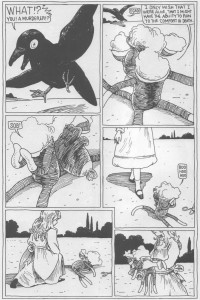

…and then a strange lament which is so at odds with everything we have come to expect from the animate toys of fairy tales and children’s books.

The final two pages are beautiful in their simplicity and absolute conviction.

The monkey’s external appearance mirrors his torment and emotional disfigurement. He finds it impossible that anyone should love a murderer, an object which is “undead, unalive, a souless monster”. His owner’s answer is unambiguous in its certainty: “How can I not love you? You’re my sock monkey…”

This short story has a spiritual depth of feeling which seems out of place in Millionaire’s oeuvre. Yet the markers abound: there’s the Jacob’s ladder produced by the crow on the second page which was once a source of amusement for the monkey; a passage to the upper reaches of his known universe; and then a hint at sacred communion in Anne-Louise’s upstairs bedroom. The baby bird is a creation which is both beautiful and good; the monkey’s final acceptance nothing to do with his moral worth but love and repentance. I do believe the artist is an atheist (so was Tarkvosky in his early years by some accounts), which makes this story that much more remarkable and this interpretation, in all likelihood, specious.

Many will find this tale shallow, inconsequential or sentimental but it captivated me the first time I read it. Perhaps it appealed to my sense of childhood anguish. I’ve never wanted to read it again, not because of any lassitude but the firm knowledge that these nascent feelings could never be reproduced. Nor have I cared to write about it up till now, presumably out of some fear that the process would diminish its capacity to enchant. In that, at least, I was wrong.

***

Notes

[1] Richard von Busack identifies this with Johnny Gruelle’s Raggedy Ann stories.

Such a lovely piece, Suat.

The Christian interpretation seems fair enough — that kind of imagery touches Christians and atheists alike. It also seems fairly clearly about parenthood though, both in the sock monkeys guilt and in his owner’s love. it does seem very much in the tradition of children’s stories and fables in that too.

The language is beautiful too as you say. I’ve never really read any Tony Millionaire; I may have to get some now.

No need to be so afraid of reading it again, Suat, that is actually a beautiful story that fully stands up to re-reading, or re-viewing (and I’m saying this as one who lives with the original art for one of its pages right above my bed, so I see it every single day). Just because the medium is in its infancy does not mean that every work made in it is too–but of course you know that. I don’t think it’s out of place in Millionaire’s oeuvre either, it just fully foregrounds the poetic melancholy that can often be felt underneath many of his other stories. In the same vein, I would also recommend his “album” (it looks just like a European BD album), “Uncle Gabby.”

Thanks, Noah. I’ll agree with all of that. The concept of “parenthood” is probably part of the Christian make-up, as can be seen in the parable of the prodigal son (from Rembrandt to Solaris).

Hi, Andrei. I’ll check out the “Uncle Gabby” album. You might be right about the “poetic melancholy” in his later works. I was thinking of Millionaire’s online persona and the general thrust of some Maakies strips which while humorously depressive (?), don’t quite have the same quiet, meditative quality. Which page do you own? My wife had some misgivings about putting up the page I own (the one where the monkey commits suicide). I didn’t in the end.

I have the one right between “how can I…” and “I… I’m sorry.”

I’d say that Maakies and Sock Monkey are two completely different sides of Millie’s persona. I was relating that “poetic melancholy” specifically to Sock Monkey (though you can find glimpses of it in Maakies, if you know where to look).

Thanks for sharing that, Suat.

Pingback: Super Doomed Planet » Blog Archive » Links to Things