In his post, Eric argued that Moore’s Swamp Thing is feminist, both because it presents Abby as a strong, heroic figure and because it critiques Swamp Thing’s own abusive use of patriarchal power.

I agree with Eric that power and gender are both important themes in the Swamp Thing series. I’m less certain that Moore always manages to be especially thoughtful about them, though. It seems to me, on the contrary, that in the marriage between Moore and his tropes, it’s as often the green, lumpy pulp that wears the jeans in the relationship as it is the feminism.

Having brutally murdered that innocent metaphor…I thought I’d look back at the same issues I discussed in my first post — the two-part story in which Swamp Thing goes to Rann.

This story is built around doubled couples: Swamp Thing, in exile from earth and Abby, is mirrored by Adam Strange, who is in a constant vacillating exile from Rann and his wife, Alanna. In both of these pairings, the male/female roles are apportioned in familiar manner. Swamp Thing and Adam are the seekers, questing across space, engaging in feats of daring-do, in order to return to hearth and home embodied by Abby/Alanna. Female means stability and civilization; male means adventure and rough virility. Moore is careful to tell us that the people of Rann are hairless, and that they see Adam as a kind of atavistic hairy monster. Alanna, then, is a (literally) smooth, perfect, (literal) princess in a tower; a fairy tale dream — just as Abby is referred to as a “Hans Anderson princess” at the very end of Moore’s run on the series.

Moore, moreover, links his males questing nobly for the womb explicitly to phalluses and sperm. There’s one sequence where Swamp Thing gets transformed into a bulbous member spouting suggestive liquid…and look at that caption.

“Her cries like a panther’s” indeed.

Of course, that same page we’ve got Adam with that ridiculous headgear holding his smoking gun at crotch level. After that, it’s almost (ahem) anti-climactic when Swampy uses his powers to refertilize Rann…or when we learn that Adam has been brought to Rann because the “fierce vitality” of his sperm is needed to impregnate Alanna on a world where all the men are apparently sterile.

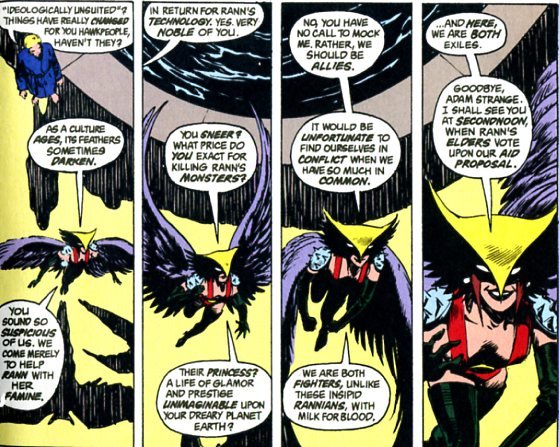

The person talking all up in Adam’s fierce virility is not his wife, but rather Keela Roo, a Thanagarian hawk warrior. Keela Roo is a very different kind of feminine. Instead of waiting at home in a castle, she sallies forth in spikes and skin and fetish boots. She wears a big flamboyant headress that stands in stark contrast to her male-subordinates unadorned helmet. She is, in short, a dominatrix and a castrating bitch; vital, animal, sexy, and unhealthily virile. Here, for example, she goes after Swampy by inserting her big phallic weapon into his split and oozing orifice.

As is generally the case in these pulp narratives, the dark queen is scary, but she’s also attractive — not least because she actually has a personality. Abby doesn’t exist (in these issues) except as a name and a desire. Alanna never speaks in English, and though her Rannian dialect isn’t entirely opaque,and though we do get to see her desire for Adam, keeping her voice from the reader effectively makes her seem distant, exotic, mysterious, soft-spoken, and unattainable. The princess in the tower again.

Keela Roo, on the other hand, has a universal translator thingee — she wants you to know what she thinks. Language is something she has mastered, and she uses it seductively. Several scenes between her and Adam have a not-very-subliminal sexual subtext. Here she is wearing that preposterous outfit while Adam talks to her in his bathrobe:

And this next sequence is a brazen come on (with Adam in a bathrobe again. Doesn’t he ever get dressed?)

That “aid proposal” seems very like a euphemism for another kind of proposal, especially as we’re getting a shot down her cleavage.

Keela Roo tells Adam, “We are both fighters,” and she’s right of course. The problem is that she’s the wrong kind of fighter. She’s a twisted fighter, a perverted fighter — in short, a cross-dressing, feminine kind of fighter, when the right kind of fighter is a male fighter.

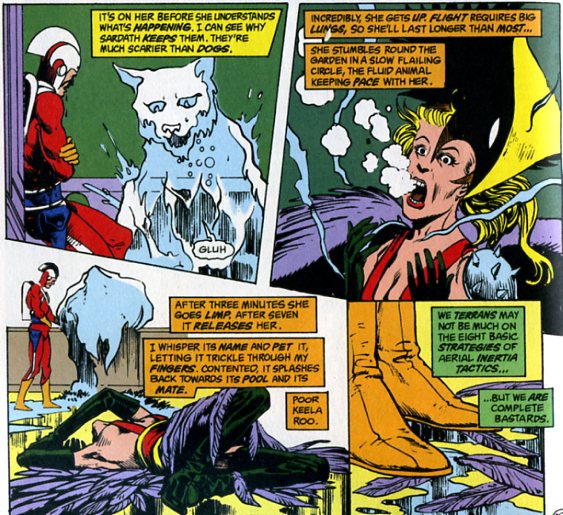

Thus, poetic justice demands that Keela Roo be killed, not in equal combat, but by domesticity itself. In battle, she manages to kick Adam Strange’s ass, but he fools her by leading her to his home, where his household guardian water creatures disposes of her. She is, then, not merely defeated, but humiliated — her fetish mask is torn from her, stripping her faux masculinity and leaving her as just a woman after all.

In the final twist of the knife, the creature who disposes of her is itself feminine (taking the form of a cat); a liquid female personification of hearth and home, which makes short work of that other woman Adam has been dallying with so that he and Alanna can be reunited again.

The point here isn’t that Moore is an irredeemable sexist, or even that this story’s handling of gender is particularly offensive. Rather, the point is that Moore, here and elsewhere, is using tried and true genre ideas (male quests; adventure vs. home.) And his main means for dealing with those concerns are received pulp tropes or DC comics ideas. Alanna is a princess not because Alan Moore made her one, but because some old DC writer steeped in Edgar Rice Burroughs and Flash Gordon made her one; the hawk woman is dressed like that because some pulp dc writer steeped in pulp cheesecake figured why the hell not.

Moore takes these ideas and runs with them…but though he runs pretty far, he doesn’t necessarily run to a different planet. In space opera, good women are beautiful paragons who sit at home being good and nurturing; bad women are aggressive and dominant and get killed off despite (or because of) their appeal. And that’s the way it is in Moore’s space opera as well.

Eric argues that at the end of the series, Moore undermines standard pulp narratives about revenge, domestic bliss and male power. But to me at least, reading back through some of these stories, Moore’s use of pulp in Swamp Thing seems less like undermining and more like assiduously and inventively cultivating.

__________________

You can read the whole Swamp Thing roundtable here.

Jog’s massive concluding Swamp Thing blowout post will be up tomorrow.

I never said he “always” manages to be thoughtful about them… He is thoughtful about them…and that thoughtfulness becomes important from time to time in the series. Sometimes he tries to say something deep about them and fails (as in the werewolf issue–as I say)–and sometimes, he doesn’t seem to be paying as close attention.

I would say that feminism is usually part of his project–but that there are different kinds of feminism and they don’t always get along. His “second wave” feminism–appreciation of, and celebration of, stereotypically feminine “values,” may lead to a lot of stereotyping (as you note here). He’s a self-conscious valuer of “feminine” principles—but this means defining some kind of “essential” version of gender, which is less comfortable for both first wave and third wave feminist thinkers. It can also come across as somewhat condescending coming from a man. Balloon-breasted castrating hawk ladies are not the high point of the series in terms of its representation of gender. I’m not sure it means Moore isn’t being “thoughtful” necessarily though– Strange’s idiotic blasting away at Swampy is clearly a critique of “typically masculine” behavior–The problem here is often in how the “typically” bleeds a bit too much into the “stereotypically.”

The immensely overwritten, but still kind of fascinating, “loving the alien” issue is more self-conscious in its manipulation of overly familiar tropes. There, the “mother” is machine, not Earth, is rapist, not potential victim–and Swampy (the man) has to take the stereotypically feminine position as rape victim–as “nature” being tilled by industry. It’s all a bit on the obvious side, I guess–except for its reversal of genders–“she” becomes the machine-like industrial rapist, and “he” becomes the “earthy” mother figure–even though neither of them, strictly speaking, is gendered at all (at least not in any traditional human way)–since one is a swamp monster, without functioning reproductive parts–and the other is a planet/machine.

Swampy himself vacillates between being a “feminine” “mother earth” figure–and a masculine foil to Abby.

Can’t believe you sucked me back into this.

His shift to more “third wave” ideals in Lost Girls and Black Dossier contrasts with the kind of second wave thinking in most of the Swamp series.

“Strange’s idiotic blasting away at Swampy is clearly a critique of “typically masculine” behavior”

This is the disagreement. That scene is a standard-issue mistaken-identity super-hero fight scene. It doesn’t have bad repercussions — Swampy doesn’t die and Adam doesn’t end up altering his behavior in any noticeable way afterwards.

In fact, to me it doesn’t seem like a critique of pulp masculinity, but like a celebration of it. Adam’s defeat of Swampy is righteously bad-ass — decapitating him, strapping a rocket-launcher on him, and shooting him into the ether is both smart and viscerally effective. Moreover, the overheated interior monologue has Adam very sensuously imagining sex with Alanna — the connection between sexual success and manly combat skills couldn’t be much clearer. I guess you could say that the Rannians ridiculing Adam for his apeness at the end is a kind of critique — but it’s pretty clear that they’re close-minded lame-asses, and unvirile to boot as we later learn. At most, the way the whole thing is over the top seems like gently affectionate parody.

Along those lines…why are the gender roles here second-wave, and not just, you know, traditional pulp gender roles? Moore doesn’t promote “feminine” virtues — Adam wins by being a better fighter (more of a bastard, as he says) than the hawk woman; Alanna doesn’t get to talk much and is treated more or less as a prize of war, men do manly things, women do womenly things, and when they don’t they get killed.

I mean, I think you’re right that Moore is interested in feminism, and works it into his stories in various ways. But, at least in Swamp Thing, I think he’s way *more* interested in genre and pulp, and when genre and pulp collide with feminism, he tends to go with the genre.

Seeing a “critique” of Swamp Thing’s revenge, for example, requires you to (a) interpolate a criticism of ST that nobody in the comic actually voices, and (b) ignore the fact that, again, the revenge is really extremely clever, vicious, and generally loads of fun. If Moore wanted you to feel sorry for the guys who get killed and show their humanity, he could have done that — but instead he shows them being sexually deviant, selfish, shallow, and generally contemptible. He’s not doing a “critique” of patriarchy. He’s doing a revenge narrative, and having a blast with it.

The space-rape story does interesting things with gender, I agree…though I’m not really sure how you get a feminist message out of it exactly. It’s still working with the guy-as-questing-sperm motif from the Adam Strange stories, mostly — and with female as castrating, bitch who has to die for her sexual aggression, for that matter. It’s a pretty entertaining take on those motifs, just as the hawk woman in the Adam Strange two parter is a great character in a lot of ways. But actual critique of gender roles? Working actively and effectively against the pulp tropes he’s been handed? I just don’t see it.

The mistaken identity thing makes it pretty clear how stupid Strange is being–He blasts away without thinking. It is a typical trope of superhero stories–but given Moore’s usual attitude toward superhero tropes (to deconstruct them, not just use them blindly), it seems clear to me that there’s some criticism involved of the tropes–and therefore of the acts. The look of smug satisfaction on Strange’s face as he “kills” (or thinks he kills) the hero of the book clearly shows him to be a dope (both for unthinkingly killing a fellow superhero and Earthling–and for thinking he has actually killed him, which the reader certainly knows is not the case). The Rannians treatment of Strange reflects poorly on them, for sure–but when he acts like an unthinking ape, it also reflects poorly on him. He sees himself as a “monster killer” with no sense of the fact that “monsters” are what he/we make of them–not inherently evil. The fact that its Swampy that he thinks this about indicates Strange’s complicity. All of which is to say that the book does use typical tropes of the genre–but puts a twist on them. Typical superhero “mistaken identity” battles have no killing, have no interior monologue where one hero thinks of the other as a “monster,” etc. They also usually have no intentional commentary on gender and power. Since all of these things are part of the series at large, when they come up in these issues, they invite some interrogation.

“Second wave” in the sense that the series works not just to portray women as domestic earth-mother types–but to “value” that type–often over-and-against typically masculine values.

You’re the one who pointed out that Keela Roo is killed by the “domestic” btw. It is strange that kills Keel Roo–but it’s also a certain kind of femininity (something you pointed uto)

As for the revenge thing. It’s true that Moore will always aim for an entertaining badass presentation–and it’s true that making revenge seem “cool” can work against any kind of critique of power, violence, etc. At the same time, Watchmen is clearly aiming at a critique of power, but makes Rorschach seem the most cool and badass dude around. Sometimes Moore’s politics and his use of pulp tropes (or even just his basic dedication to make his characters complicated and interesting) can conflict with each other. I don’t deny that (in fact, I highlight it elsewhere–in a mysteriously vanished internet article)–but that doesn’t mean that the politics aren’t there–and often/usually intentionally so. Moore often said that his intention with Rorschach was always to have people NOT identify with him and find him cool–but rather to find him disturbing and disgusting–all as part of a critique of his fascist value system. Just because this often backfired with Moore’s readership doesn’t mean the critique isn’t there….

The alien story, I suggest, has some “third wave” feminist elements–which basically means a confusing of, or critique of the notion of gender entirely (and is basically inconsistent with second wave notions). By reversing typical gender roles in potentially un-gendered characters, Moore screws around with conventional notions of what sex/gender is, potentially destabilizing the male/female division. I haven’t re-read that one in a long time (I think I skipped it last time through)…and I’m not sure I would even make a strong case that it quite does what I suggest in this paragraph. I’d have to read it again…but I’m also not sure I’d call the machine/alien thing a “bitch”–or even “castrating”… She rapes Swampy–which might be seen as “castrating” from a power p-o-v, but she hardly has the attitude (or the outfit) of Keela Roo. She’s a kind of “benevolent power” figure, I think (as opposed to a bitchy power figure)–She hardly conceives of herself as doing anything wrong–or anything out of her nature–She “loves” Swampy. In fact, one could see this as a mirror of the Dennis/Liz relationship too–A power exerted out of “love” without cognizance of its damaging effects. Am I sure that this story, the Dennis/Liz story, and the final Abby/Swampy pairing are meant to be mirrors of each other. Not sure–but once you start seeing the pattern (and it keeps turning up) it seems less likely to me that it’s some kind of cosmic accident.

I just don’t think the only choices are “intentional feminist critique” and “cosmic accident.” There are things you can do with pulp tropes that aren’t necessarily critiques (like celebrating them, for example.)

Strange kills swamp thing and then gets to run off and sleep with the girl…and then uses the same skills/methods he used to kill Swampy to save the day later on. If Moore intended a critique of masculine pulp tropes, I would say he thoroughly fucked up (as it were.)

Promoting feminine domesticity really is not particularly second wave, is what I’m saying. Second wave hates domesticity, bless its black heart.

I guess you could see the anti-nuclear war message as being validated by the domestic victory of the water creatures — but since the problems are basically solved through violence and the brutal death of one’s enemy, that comes off as being fairly dumb, I think.

You can bte Octavia Butler or Ursula K. Le Guin, for example, wouldn’t present the alternative to violence as being more/different/better violence.

I wouldn’t call myself an expert on feminism–but I don’t think there was anything particularly black about the second wave. In fact, black feminism tended to split with those who saw themselves as plain old (white) “feminists” at that point I think. Defining the various “waves” is a tricky thing anyway.

There is something problematic/condescending about a man promoting some kind of positive “earth mother”/domesticity as a critique of patriarchy…but I do think that Moore does so–by critiquing masculine power, violence, and hierarchy (as Woolf does in something like 3 Guineas) and trying to find an alternative rooted in stereotypically “female” values.

The notion that the solution to violence is more/different/better violence is obviously pretty dumb–but while that may seem to be the “answer” at the end of these Strange stories, I think the entirety of the Swamp stories suggest otherwise (and Moore often suggests otherwise)–There’s the “love not war” message in Lost Girls, of course–but there’s also the critique of super heroics and super powers in Watchmen (and the fairly explicit critique of using violence to solve violence in the Ozymandias case), the death and withdrawal of V for a “kinder, gentler” Evey in V, the “let’s make friends” Tom Strong stories (who almost always solves his problems with his enemies by making nice-nice), etc. One can argue that Moore was just kind of screwing around for fun in Swamp Thing, with the power/gender stuff only turning up by accident or inconsistently. I don’t think this it’s an accident–but there is some unevenness. Sometimes, as in the Strange story, the results are ambiguous–or problematic–I wouldn’t deny that… I would point out that I don’t even remember the anti-nuclear bits of these stories. I could reread them to make some sort of case, I guess–but I won’t. I would point out that the entirety of issue #50–the big American Gothic blowout–worked as a deflating of expectations of violence. Swampy “reasons” with the big black thumb, rather than trying to fight with it—the model is negotiation, not power struggle (and he uses plant/ecological metaphors to put across notions of interdependence as opposed to hierarchy). This whole issue was kind of a dud–but it does indicate Moore’s effort to get a certain kind of politics across even in those issues.

Strange is painted as a dope when he blows up Swampy. Part of that is his belief that violence solves problems. The fight with Keela Roo is more self-defense and is, perhaps, more excusable on those grounds.

On a basic level though, superhero comics are built on fights and violence. These tropes do play against any comprehensive anti-violence message since you can’t have superhero comics without fights. Moore’s turn away from superheroes (brief though it was) had something to do with his discomfort with genre tropes. “Discomfort” politically and philosophically, anyway–since he’s obviously very comfortable manipulating them.

Not “black” as in “african-american” — black as in dour, cynical, and mean-spirited. Second wave is pretty mean and bleak compared to third wave — much more about criticizing than about making a happy new world. I like that about it.