The following essay is by Bert Stabler, an art critic and sometime contributor to HU (when I can browbeat him into it!) Bert’s own blog is here. His website is here.

_______________________

Carolee Schneeman’s “Meat Joy,” performed at The Plagiarism Festival on February 6, 1988 @ Artist Television Access, San Francisco, CA.

Girl Germs: Nature as Abjection in Early Feminist Performance Art

Bert Stabler

Immediately after confessing her “ambivalence” about the politics implied in her re-staging of Carolee Schneemann’s classic 1975 performance “Interior Scroll” (in which Schneemann read aloud from an unrolling script contained in her vagina), Gretchen Holmes goes on to summarize her recent review of Tina Takemoto’s alternately ironic and therapeutic work at SFMOMA thusly: “Takemoto simultaneously engages feminism’s politics and its steaks, and this dual presence argues for the importance of both. “ A more fortuitous typo could not be imagined. Possibly Schneemann’s second most well-known work was the more lavish 1964 performance “Meat Joy,” in which several mostly nude performers cavorted with raw fish and chicken meat, as well as sausage, paint, clear plastic, scraps of paper, and various other items. Schneemann’s use of inert objects alongside exposed flesh in “happening”-style improvisations was established in the 1962 piece “Eye Body”, in which she covered herself in grease, chalk, and plastic, and performed in a “loft environment, built of large panels of interlocked, rhythmic color units, broken mirrors and glass, lights, motorized umbrellas.” This dynamically grotesque and erotic theatricality, typical of Schneemann’s assertion of gendered embodiment, was conceived of in direct confrontation to the uninhabited female bodies in high- middle- and lowbrow art, film, and publishing.

Carolee Schneemann, from the performance “Eye Body.”

Pioneering “feminist body art” is widely recognized as Schneemann’s artistic legacy, which has now been handed down through the gruesome sculptures of Kiki Smith, Cindy Sherman’s grotesque theatrical self-portraits, and Patty Chang’s identity-themed actions. But in a way different from these artists, Schneemann, as well as other early performance artists, seemed to take on language itself, not as a weapon but as a target. Much of Schneemnann’s contribution to art may seem to many viewers both now and in the past as simply some sort of empowering avant-garde appropriation of pornography—from her 1965 erotic mixed-media film “Fuses,” to her 1981-88 “Infinity Kisses” photo series, in which she makes out with her cat. The ritual aspects of what Schneemann repeatedly referred to as “shamanic” gestures have been largely smoothed over in the process of her institutional canonization. But despite the anti-essentialist language games of postmodernity, the connection between ecstasy, flesh, faith, and sickness is not hard to see. Indeed, Genesis offers the first female rebel, and a vision of punishment not for nakedness but for shame in nakedness. Connections between femininity, sacrifice, animals, and blood continue throughout the Bible, with the Gospels of Mark and Luke narrating the healing of a man possessed by a legion of demons, dispersed by Jesus into a herd of pigs, followed immediately by that of a woman who had bled ceaselessly for twelve years, and the resurrection from the dead of a young girl. While Schneemann’s attitude toward Christianity is hardly congenial, that hardly mitigates the importance, within a Western religious paradigm, of staking out a religious space within fine art in a way that few others have, in performance art or otherwise.

The influence of Antonin Artaud’s “Theater of Cruelty” runs throughout Schneemann’s work but also throughout the history of “edgy” performance, from Allan Kaprow’s Happenings to Joseph Beuy’s “social sculptures,” through the ecstatic bloody festivals of the Viennese Actionists, to G.G. Allin, the Survival Research Laboratory, and the good old Blue Man Group. But by unabashedly casting herself not only as a feminist but as a “shaman” (not of the crystal-healing variety, mind you), Schneemann marked as both spiritual and political a practice of staged self-destruction and resurrection that illuminated a particularly female psychic crisis that was no mere reflection of or supplement to the Oedipal scene. Ana Mendieta smearing blood on the wall or immolating her own excavated silhouette, Marina Abramovic enduring the experiences of staring into an industrial fan until passing out, carving a pentagram into her flesh, having a strung arrow pointed at her chest for twelve hours—these melodramatic but thoroughly sincere acts differed in important ways from the Duchampian hijinks of their male performance counterparts like Vito Acconci and Chris Burden (or today, William Pope L or Santiago Serra), the esoteric shrines of Beuys or of Paul Thek, or the brutal austerity of object makers like Richard Serra or Carl Andre (the latter acquitted of Mendieta’s 1985 murder).

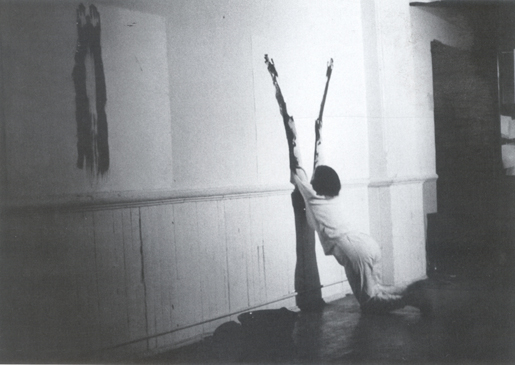

Ana Mendieta from the 1982 performance “Body Tracks (Rastros Corporales).”

The bluntness and savagery of Schneemann, Mendieta, and early Abramovic even distinguishes them from the more unambiguously positive performance gestures of Suzanne Lacy, Yoko Ono, or Annie Sprinkle, or the open-ended, research oriented, socially-engaged art of recent years, from artists like Paul Chan, Rikrit Taravanija, Trevor Paglen, and Walead Beshty, or groups like the Center for Land Use Interpretation, Futurefarmers, or Temporary Services.

Indeed, there has been quite a bit of utopian imagining since the millennium, both within and outside the art world, now that the memories of revolutionary massacre, even viewed from afar, are at least a generation removed for most young people. It’s a commendable project, since maybe the greatest thing the art world can offer, and the real world cannot, is a vista of endless possibility within grasp, a horizon brought near by the omnipotence of fantasy. Ideas can be brought forth and realized with few negative consequences– except for perhaps the debilitating psychic effects of narcissism and solipsism, as well as the general alienation and transgression fatigue engendered by the ceaseless breaching of propriety. Nonetheless, spreading blood on the wall or rolling in meat are probably incapable of losing their impact—they are as clear and democratic as a mystical gesture can be. The pre-linguistic vulgarity of early feminist performance is what, in some way, makes it some of the most successful work of the last 100 years.

Every phase of the last century has seemed to singularly exemplify one of the aspects that has made the modern period such a rich antiquity for contemporary art to plunder. The twenties had the technologically sublime and abject, the thirties had apocalyptic populist authenticity, the forties had spastic mystical authenticity. After the alleged end of modernity, the zeitgeists marched onward. The eighties had self-aware commerce, the nineties had identity pastiche, and the oughts had virtual communities. And In between the classical and the decadent, the seventies simply offered charismatic brutality. There was Idi Amin, Pol Pot, Pinochet, Jim Jones, Henry Kissinger—but, more to the point, there was the rise of pulp horror cinema, a vivid and vicious ethos crystallized in films like “I Spit on Your Grave, “The Last House on the Left,” “Lipstick,” and other films of the “rape revenge” genre, which made the castration of patriarchy explicitly public. Similarly, the theme of homicide was certainly a presence in religiously-inflected performance. In “Revolution in Poetic Language, “ Julia Kristeva says, “Opposite religion or alongside it, ‘art’ takes on murder and moves through it… Crossing that boundary is precisely what constitutes ‘art.’…(I)t is as if death becomes interiorized by the subject of such a practice(.)” The ideological weight of such aggressive feral gestures as those of Schneemann and the artists she influenced was momentous, and seems no less epic from here. Going forward, it is worth remembering how political art was temporarily not confined to the linguistic and cerebral, and eroticized pantheistic death-worship was for a moment neither ironic or gleeful, but deadly and political.

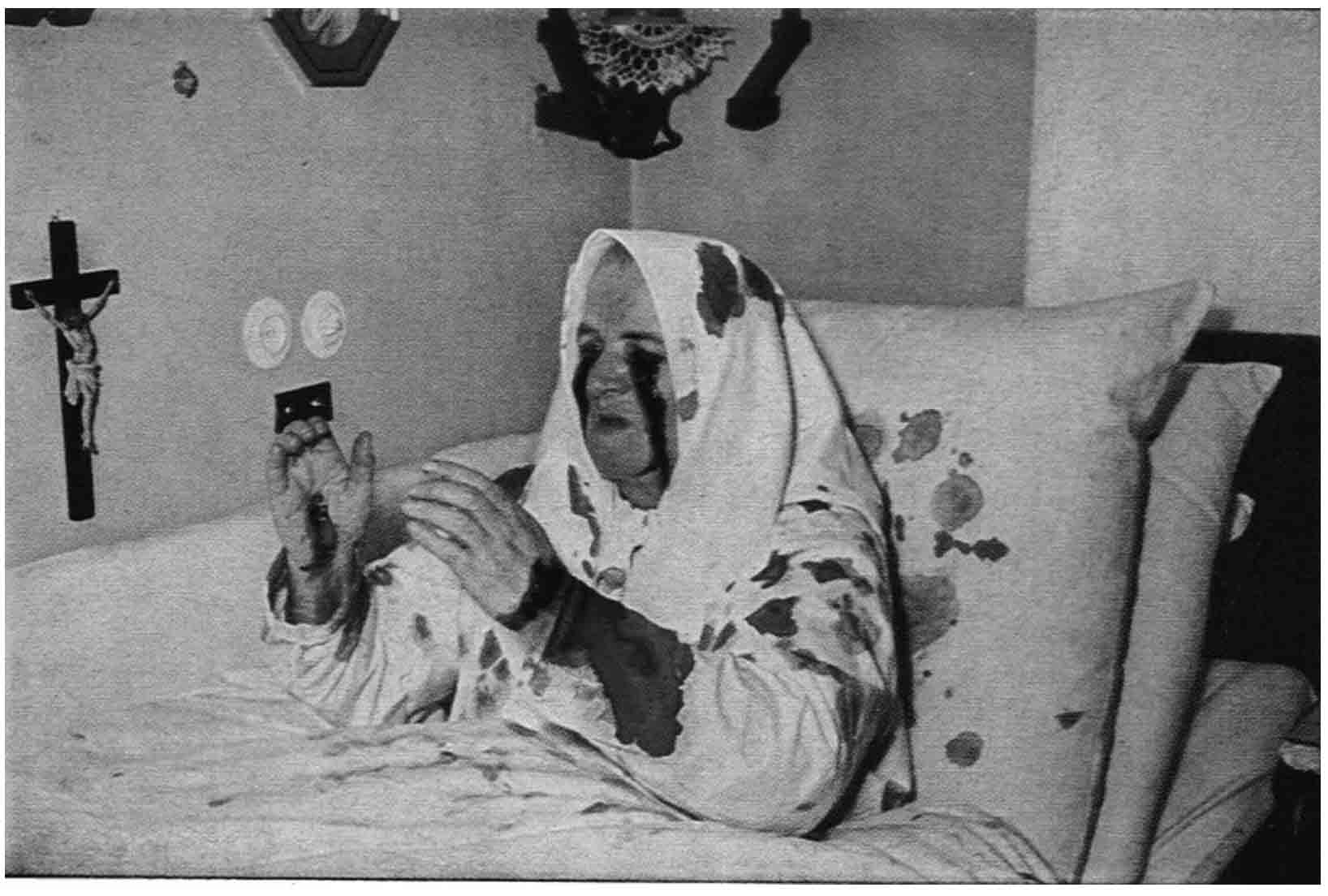

Therese Neumann, a Catholic mystic stigmatic who was threatened and intimidated by the Nazis, and reportedly ingested nothing but the communion wafer, once a day, from 1922 until her death in 1962.

It’s interesting; that video (which I added, not Bert) seems somewhat ironic and gleeful; at least the audience seems pretty cheerful. I wonder if Schneeman’s original performance was more deadly, as Bert suggests in the last sentence.

This also seems to connect to Caro’s essay on Anke Feuchtenberger, at least somewhat. Intense experiences of gendered embodiment — though the ones here seem less explicitly linked to sex than in Feuchtenberger’s work maybe….

I’m dying to watch this but I am unfortunately getting Internet at my parents’ using my cell phone as a modem, which makes this a no-streaming zone.

If anybody has an email-able version of the vid, or knows where I can download it, please send it to me?

Bert, so much to talk about…cool.

Here’s a bit:

I’d put it as “the anti-essentialist postmodern games of language,” rather, especially in this context, where the point is the body, which unlike consciousness has an unmediated access to the Real. I don’t think that makes any difference in your point except that I think it’s not a “despite” but an “as illuminated by.”

Also this:

Have you thought about Oedipus at Colonus in this light? I was struck by the bleeding eyes of the mystic, the power Oedipus finds in his blindness and the way it is the impetus for Antigone’s ate…the key Oedipal scene here isn’t the Freudian one, but stabbing out his eyes. And it is explicitly both spiritual and political.

I’m not really sure where I’m going with that…

Does Freud do anything with the stabbing out of the eyes? Isn’t it related to castration and the primal scene?

I think with postmodernity, Bert is contrasting other performance art traditions, and especially maybe more contemporary art that points to ritual with maybe a more ironic bent.

This does make me think though of some black metal, particularly Blood of the Black Owl, a band I talked to Bert about recently. That’s not female though; more like male spirit journeys which always makes me think of Robert Bly which is not good at all.

Blood of the Black Owl doesn’t have the same sense of debasement exactly, though; they and bands like Drudkh are about gathering power from ritualized folk sources, rather than emphasizing bodily vulnerability in the way this seems to….

Yeah, he probably does read the stabbing as a response to the primal scene, Noah; that seems right. But I think the intended classical interpretation is more satisfying: blinding as “poetic justice” for the “blindness” that kept him from recognizing his mother and father. At Colonus of course he’s already blind, and the context is “spiritual and political”: supplication to the Eumenides and the political wrangling of Oedipus’ sons.

Maybe I’m trying to get at the idea that this physicality isn’t debasement in the religious or classical contexts. Instead it’s what made the mystics so scary in the middle ages…they way their physical suffering provided an ecstatic proximity to Christ, unmediated by the male- and linguistic-dominated priesthood.

I don’t think I’m disagreeing with Bert.

Grrr, stuck. Need video.

Hey, thanks! Not too much time now, but do you guys have thoughts about Antigone? Maybe it’s Melanie Klein who talks about it… I don’t remember. But yeah, the female moral compass outside of the law… is it Kirkegaard who says that mourning the dead is the essential moral act? Anyway, that’s just one thing I wanted to talk about but didn’t, along with the undifferentiated womb, and primal being..

I like your idea about the mystics with direct access to Christ, Caro — but were they considered scary (or just scary) in the middle ages? They were pretty into their saints back then, I think, both male and female, weren’t they?

Similarly, I think the Antigone comparison may be overly binary in some ways. That is, in the play, I think there’s a pretty strong contrast between the law (male) and blood bonds tied to bodies (female). Whereas, I think in the Christian context (shamelessly stealing from Niebuhr) the contrast between law and love is more complicated. Specifically, Niebuhr says that love is both the fulfillment of the law and a scandal in the face of the law. So from that perspective, mortifying the body to become like Christ can be seen as repudiating the law (as Antigone does) but also as fulfilling it — being more Creon than Creon. In gender terms, I think that maybe also gets at the way that Christ is always a feminized figure (disempowered, penetrated, associated with love, etc.) so that, in Christianity, the ultimate law can actually be seen as female (which I think is a logical conclusion, though probably heterodox in some ways.)

I think this fits pretty easily into a feminist context for performance art like this — the female body is presented as a repudiation to male authority, but also perhaps as a purified, ideal authority. I do wonder if it really works as well in terms of generalized pagan ritual as it does in a Christian context though. It may just be my atheist prejudice, but, for instance, in the video, the drumming to indicate weighty ritual and primal oomph — I find that kind of cliched (and maybe even somewhat unfortunate in its appropriation of denuded Indian/African/what have you sources). Also, the purified authority side of the dynamic doesn’t seem as worked out/clarified as it does in a Christian context — we’re a good bit more on Antigone’s side than Creon’s with Scheemann, whereas the balance seems a lot more difficult to tip one way or the other with Therese Neumann who is explicitly mortifying her body in the context of, and in some ways in honor of, the earthly church, as well as an unearthly God.

Excellent. Here are a couple things– the church is significantly better off as a non-state actor, the separation of church and state benefitting the church just as much as the state probably. Render unto Caesar, etc. So Therese Neumann can stand as a figure of defiance to the Nazis (Christianity could have used more of those), just as Christ is always a figure of passive defiance, as is Antigone, in that she’s attending to private bodily-spiritual affairs, not acting aggressively against the state but resisting the state’s aggression (MLK/Gandhi-style).

I still haven’t watched that video– the whole issue of reperforming performance art pieces is something I touched on with that Gretchen Holmes article (and I have written about Mark Tribe’s reperformance, and a big 1968 rally reperformance in Chicago in 2008), but the colonialist implications of white people drumming naked in body paint is clear. But it’s also unavoidable– modernity is bound up with colonialism. It doesn’t devalidate Carolee Schneemann (especially in a reperformance) any more than it devalidates Elvis.

I’m working with the idea that the body lines up with soft boundaries, pre-language stuff which is always a contingent post-language non-body recapitulation of something lost and an attempt to name something unimaginable, a space for God that includes law but is not identical with it.

It does devalidate Elvis though; he takes tons of shit for it from various quarters (Public Enemy most famously.) I mean, I love Elvis, but Chuck D isn’t completely out of bounds either.

Also…there’s an argument to be made that the culture Elvis was appropriating was in fact his culture. Poor white and poor black culture is pretty mixed — and the culture he was taking was specific. I think the generalized borrowing of an idea of atavistic authenticity is different.

I don’t know; I don’t need to make a big deal out of it. But saying modernity is bound up in colonialism (or vice versa) seems a little too easy. Sometimes art confronts or deals with its colonialist implications in interesting or thoughtful ways, sometimes it doesn’t. To me this doesn’t really seem to, whatever its other virtues. (Though again, this might well be different in the original performance — hard to know what they changed or how.)

Colonialism is evil. There seems no clearer statement of evil in how the modern state functions, from Rome to now.

Individual appropriation of cultural forms is not unrelated, but (to borrow from another discussion with you, Noah) if we’re not going to assign moral superiority to the oppressed, who must constantly appropriate the culture of their oppressor, I think there has to be some space for the oppressor to appropriate from the oppressed. For me to feign solidarity with the black struggle by sneering at Led Zeppelin is morally irrelevant.

Sure, the essentialist shamanic thing has problems. But Carolee Schneemann was hardly the first white artist to use motifs of pre-modern cultures in modern art, and I think she did something much more interesting with it than she’s often given credit for (by folks who dismiss her work, and feminist performance generally) for being all shamanic and essentialist.

Okay. So what do you think she is doing by appropriating fairly undifferentiated cultural tropes? It seems to me like she’s interested in other issues (around gender and bodies) and is using quasi-Indian drumming as a marker for primitive/spiritual. That seems both cliched and problematic to me. Do you feel she’s not doing that? Or what are you claiming she’d doing in reference to the cultures she’s appropriating?

Elvis is kind of complicated, in that he was working in a segregated milieu, and so appropriating black forms (which were also to some extent his cultural forms) was at least in part, and taken as the time as, an integrationist move. I don’t think he was really fighting the power exactly, but there was something there which was taken as scandalous and politically relevant at the time. I don’t see anything happening with Schneeman’s appropriation which is similarly double-edged…but I could be missing it.

I don’t need you to acknowledge that, if Schneemann and the Judson Church folks used hand drums, that there were no problematic primitivist connotations. But I see problems with that kind of narrow reading as a primary way of processing art. What if they used electronic drums? What if they deliberately did not syncopate? Would that make it okay?

In a culture deprived of any kind of invisible centering principle, you end up with lots of different ways of resisting the march of futuristic progress. One way is primitivism, and I think it can be iluminating as well as possibly somewhat boneheaded.

It would make it really different if they used electronic drums and didn’t syncopate, sure. But they didn’t do that because if they did they wouldn’t get the requisite primal oomph. Right? The whole point of doing it the way they did is to reference a stereotypical view of these cultures as atavistic and authentic.

This is why Led Zeppelin seems, to me, less irritating than, say Eric Clapton. Zeppelin uses the blues as a blueprint, and they’re getting something from that obviously, but they also take it somewhere else, where the primary point really stops being “I am cool like these primitive American black people.” (Instead it’s “I’m cool like these Vikings,” for example.)

I like lots of art that makes use of primitivism, from Elvis to Led Zeppelin. But this iteration does seem boneheaded to me, in a seriously boneheaded way that makes it difficult for me to get past it. It’s doing something that can often be a problem with feminism, which is appropriating minority experiences, repurposing them as female experiences, and not acknowledging the resultant power dynamics. (At least, I don’t see it acknowledging the power dynamics. I can be convinced that it is if you’ve got an argument.) I appreciate the positive things you point out about it too, as I tried to say above, but given the history of specifically this sort of thing, I just have trouble getting entirely on board.

The other thing I kind of wanted to talk about was taste– which I think is a lot of the issue. Led Zeppelin and Elvis avoid being racist, to many people, based on how good their music is– even though they appropriate specifc songs by specific black artists.

On the other hand, rolling around naked in paint with fish is probably not a specific act belonging to a specific conquered people. I think the complete vulva-pounding grotesqueness of early feminist performance would be celebrated if it was phallic.

Again, yes it’s primitivist, but so is jazz and Picasso. The taste issue works in a pretty interesting way politically, I think.

I like the grotesqueness! It’s really grotesque; that’s the thing I like about it. Other things I’m not so sure of.

Picasso gets all sorts of shit for his appropriation of primitiveness too — as he should. Are you thinking of white musicians playing jazz in particular? It’s weird to think of that as appropriation in some ways, since jazz was such an integrated music from very early on.

An interesting person to throw in the mix is Wanda Jackson, who is obviously a lot like Elvis…except that she actually integrated her band, which was a big deal for a country artist in the early 60s.

The thing about appropriation is that specificity is your friend, often. Covering a particular song is referencing a particular song — the less specific generalized appropriation of a stereotypic atavism seems like maybe more of a problem. At least potentially. To me.

The other thing with taste is you get into the “I am progressive; I like Dynasty; therefore Dynasty is progressive” argument. I mean, I love Led Zeppelin, and I’m willing to argue that they did interesting things with their appropriation…but, of course, they also failed to give proper credit often. If someone said they weren’t going to listen to them for that reason, I don’t really know that I have an especially strong response.

I guess what I’m saying is that execution isn’t everything. Dynasty is probably really not progressive no matter what. Carolee Schneemann did something with art, specifically with the new form of Happenings, that no other artist was doing. There were comparable artists around, as I said in the article, but doing something that was so patently disturbing, especially as a woman, made fine art a lot more meaningful to many people, I think, and women in particular, without losing a shred of aggression.

But yes, just as with Elvis and Led Zeppelin and Joseph Beuys and whoever, lots of people don’t like the way in which the work is transgressive. Using a vague stereotype (which I’m not even sure I concede she did– I need to watch more video) is regrettable. It’s more regrettable, however, that art doesn’t offer a lot of perfectly simple and clear, yet thoroughly pretty mind-blowing events like Schneemann’s.

Well, I will stop hectoring you about it! I’m curious about Caro’s take; hopefully she’ll pop up again at some point….

Caro is both behind on reading about this and handicapped due to not being able to view the video. So I don’t think I’m coherent yet on this topic.

I’m in agreement on the Claptop v. Zeppelin issue, and I noticed this:

It struck me first as very wrong, because I immediately thought of tiki-in-the-atomic-era. Then it struck me again as very right: the way a stiff drink in a tiki mug really mitigates anxiety about Bikini Atoll.

Are we agreed on the reading that says the appropriation of primitivism here was meant to accrue the authenticity of anthropological primitivism to the feminist point (what Noah referred to as “reference a stereotypical view of these cultures as atavistic and authentic”)?

I ask that because my expectation was more that primitivism in feminist performance art from the ’60s-’70s would be meant to call into question the traditional discourse of “feminine primitivism” — a la Gauguin, maybe Josephine Baker, Clan of the Cave Bear, even things like Barbarella – this idea that women are more basic creatures than men, with more immediate access to the essential aspects of human experience and emotion.

I really need to see the piece before I can do more than make the suggestion, grumble.

The soft boundaries stuff is very Irigaray-an, although not so much as a pre-language thing. I’m a little hesitant about that as it does head toward Cave Bear territory. I think I’d like it though, nuanced away from the temporality of pre- and post-linguistic and more toward the mystical idea of something that circumvents language and the Symbolic order. I’m not sure it will end up somewhere meaningfully different though: I’m just a structuralist who was traumatized by too much Jean Auel as a child.

Noah, can you unpack this?

I’m lost in “scary (or just scary).”

They were sometimes considered heretics, but not always. Does that answer the question? You’re right that it’s not cut-and-dried. Maybe “threatening and in need of being contained within the conventional church hierarchy” would have been better than “scary.”

Reading this again it sort of implies that I think ’60s-’70s feminism was systematically critical of feminine primitivism. I don’t know whether that’s the case or not. I should have mentioned things like any random movie featuring Raquel Welch in an animal-skin bikini. Cinefantastique has this great Gallery of Prehistoric Pulchritude.

I’m critical of it (despite kind of liking those movies) and I think of it as fairly popular and mainstream. I also think of Jean Auel as trying (and failing, IMO) to rehabilitate it, so I was sort of assuming that the previous stuff was more opposed. But it’s possible that Auel is the last and most popular in a stream of feminists “queering” the Neanderthal sexpot…

I guess my assumption about middle ages feminine saints is that there was both an attraction and a repulsion in the middle ages and presumably later. I know that the relatively recent saint bernadette for example was fairly venerated for her suffering. There definitely was a place for saints doing fairly crazy stuff outside of the church hierarchy in the middle ages and being respected both popularly and to some extent by the hierarchy itself. I’m not sure how many of those saints/religious free actors were women, or what effect that had on the dynamic. But the medieval church definitely had a place for this kind of fanaticism, I think, such that simply saying, “suffering like christ was an affront to the church hierarchy” I think misses something important about the dynamic.. (Or that’s my impression from old medieval history classes.)

I haven’t seen any of the clan of the cave bear stuff. I don’t think Schneeman is ironically commenting on that, is my impression. Bert seems to be arguing fairly strenuously taht, irony wasn’t really where this kind of feminist performance art was coming from.

The video also manages to really not be very prurient, despite the obvious sexual connotations; it’s too viscerally disgusting — though I suppose with this, as with all things, mileage may vary.

I was thinking more about Bert’s argument re: race and taste, and posted a bit on it’s relation to Tintin here. I think the idea that you can like something despite, or maybe next to, some dicey political content is right, and it is interesting how aesthetic reactions can affect how or to what extent those dicey political bits seem to matter.

I hadn’t been checking, I’m so glad there’s buzz. First of all, let us celebrate “queering the Neanderthal sexpot.” I am clanging a large earthen bell for that statement.

Saint Theresa’s Interior Castle is perhaps the most stunning mystical vulvic manifesto/a of all time. “The soul is like a fountain built near its source and the water of life flows into it, not through an aqueduct, but directly from its spring.” And when the faculties of the soul are allowed to “sleep,” one may be temporarily possessed completely by God. Her daughters may visit the Mansions as often as desired, without permission from their superiors.

There’s no explicit irony involved in a cryptic description of erotic spiritual jouissance in the context of a highly regulated liturgical edifice. It is implied irony, but without any air-quotes. It is atavistic, but it completely melts the technology used to quarantine it.

Riot Grrl was atavistic too, imagining pre-pubescent sexuality as hermetically female. Even (or especially) Shulamith Firestone. The dream of hermetically female post-patriarchal techno-reproduction is explicitly founded on an imaginary pre-patriarchal order. There is something conservative there, to be sure, but also transcendent.

E.M. Cioran, “Tears of the Saints,” along with Bataille’s “Erotism,” are two non-feminist tracts that helped me become enamored of the intentionality behind feminist performance. The Clan of the Cave Bear/Barbarella thing is a connection that makes complete sense, and its empowerment value may be dubious, but then again there’s Betty Davis. http://mymajicdc.com/files/2009/11/betty_davis.jpg

I hadn’t seen the 1988 video until now, and I’m inclined to disavow it. I can’t watch Youtube at work (at least not without effort) and I just watched it. It seems pretty loose as a recreation.

I know I brought this up and I should be the expert, but, apologizing for that not being the case, I am going to object to the historical accuracy of the details of this video (which Noah asked me if he could embed without me seeing it and I said sure), since, even though I can’t find a video with sound of the 1964 Meat Joy, it had a lot more performers, paint and other props, no fur on the loincloths– I would still say it’s primitivist, but I think there’s quite a bit of daylight between that performance and this SF one (at the height of the AIDS crisis).

That’s interesting; more performers would definitely make it different in various ways…too bad I couldn’t find any records of Scheenman’s own performances. They may well be out there; I just didn’t manage it in the time I had….

Oh, no sweat. And I should have found out the primary Biblical injunction to enact performance art in public- it’s the Book of Ezekiel. God tells Ezekiel to lie on his left side for days on end in public to expiate the sins of his people, o make a little diorama of Jerusalem, to eat a certain amount of rice every day, cooked over a fire of human excrement. Amazing.