This essay ran in a somewhat different form in the Chicago Reader a couple years ago. I thought I’d reprint the original version along with some more pictures here.

_______________

Ever since the breakaway success of Neil Gaiman’s Sandman in the 80s, there’s been an indigenous niche for graphic fiction about brooding guys, languid girls, melodrama, the morbidly cute, and the cutely morbid. Titles like Gloom Cookie, Courtney Crumrin and the Night Things, and anything by Jhonen Vasquez exist in a parallel, twilight world, where super-heroes withered away from anemia and the American comics industry never decided to outsource all of its female genre fiction to Japan.

Chicagoan Lilli Carré’s debut graphic novel, Lagoon, isn’t genre fiction itself — it’s an art comic. But it’s aware of, and interested in, gothic fantasy to a degree unusual among alternative comics creators not named Dame Darcy. Indeed, Lagoonfunctions as a kind of meta-goth; an elliptical love letter to the genre and to its place in the adolescence of many young girls. The frontispiece drawing captures the affection and the distance — in a circular frame, Zoey, the tween protagonist, sits beside a lake passing flowers to a black, leaf-plastered, faceless humanoid thing. Flowers and tendrils frame the image, suggesting the overripe opulence of goth or art nouveau. But Carrés blocky linework is surprisingly sparse and even crude; it looks like something a precocious, motor-control-challenged Beardsley might have drawn when he was 6. The black monster is cute, creepy and mysterious in a very goth way, but the scene also has a sparse, modernist poignancy which is very different from tactile Victorian melodrama. Beauty is sketched out rather than embraced; the space between the girl’s hands and the monster’s is also the distance between desire and reticence, opening on a nostalgia which suffuses either the coming contact or its absence.

In fact, to the extent that Lagoon has a plot, it centers precisely around the deferral of the moment when the girl and the monster actually meet. The monster, or creature lives in an (ahem) black lagoon and sings. The girl’s family, and indeed, the whole town, is enraptured with the song; they go out to the lagoon to hear the music and dream and sometimes drown. Of all the characters in the book, only Zoey herself never, quite, sees the creature. When she goes to the lagoon, the black singing shape she finds turns out to be, not the creature, but her sleep-walking grandfather, waist deep in water. She sees the fire the creature sets in the woodpile, but not the monster itself; when she looks under her bed for monsters, it’s the wrong time and the wrong bed.

That’s because the creature doesn’t hide under Zoey’s bed, but under that of her parents. After the girl goes to sleep, her mom and dad have sex and then fall asleep. In the middle of the night, mom wakes up, opens the window, and lets the creature in. When the husband stirs, the creature slides beneath the bed, one rubbery, phallic limb poking out suggestively from under the frame.

Goth is always suffused with sexuality, of course. But what’s most creepy about this scene is not its gothic trappings — the woman in the dark, the vampiric monster at the window — but it’s mundanity. Zoey’s mother treats the creature with a banal casualness. She lights a cigarette (her husband doesn’t know she smokes) and offers to share it, then off-handedly mentions Zoey as if the monster knows her daughter well. The juxtaposition of small talk and amphibious interloper is funny, but it’s also unsettling. Vampire creepy is one thing; watching-your-mother conduct-an affair-while your-dad -sleeps-in-the -same-room creepy is something else.

Or maybe the two things aren’t so different after all. The solid blacks and blocky grotesquerie of Lagoon strongly recall Charles Burns’ Black Hole, a story in which adulthood is equated with monstrosity. In Lagoon, too, sexual maturity and horror are linked. But that link is mediated by a third term — a metaphor, a song. To be an adult is not to be a monster, but to follow one; not to be a horror, but to dream of one. Zoey, the child, is the one character in the book who doesn’t like (or who at least says she doesn’t like) the creature’s tune. Aesthetic response is sexual response; fantasy is for grown-up. Perhaps that’s why, when Zoey asks him to tell her a fairytale, Zoe’s dad is so thoroughly embarrassed —and Zoey simply falls asleep.

But if adult’s dream, the content of that dream is childhood. Sitting in the bog, listening to the creature sing, one of the townspeople comments that “A little sweetness can make you forget everything you want to forget for a little while.” But then he goes on not to forget, but to remember an incident from his boyhood. When first Zoey’s mom and then her dad sinks into the lagoon in pursuit of the creature, Carré draws a breathtaking sequence — bubbles floating through blackness, underwater fronds waving, and Zoe’s mother’s hair floating underwater. The beauty of the images and the dreamlike, wordless drift downward through the water, to the bottom, and finally to a completely black page, suggest sex, and death, and a return to the floating twilight of the womb. If the song is an initiation, it seems to lead as much backwards as forwards.

Where exactly it does lead in terms of the narrative is very difficult to say. After they sink, Zoey’s mother and father disappear from the story; we never find out what happened to them, if anything. Zoe may have dreamed the whole thing, or not. Her grandfather, though, is still there; he lies down with her and they go to sleep and a year passes. Then he cuts her hair, which, she notes with some exasperation, makes her look younger — as young as she looked a year ago, a couple of pages before.

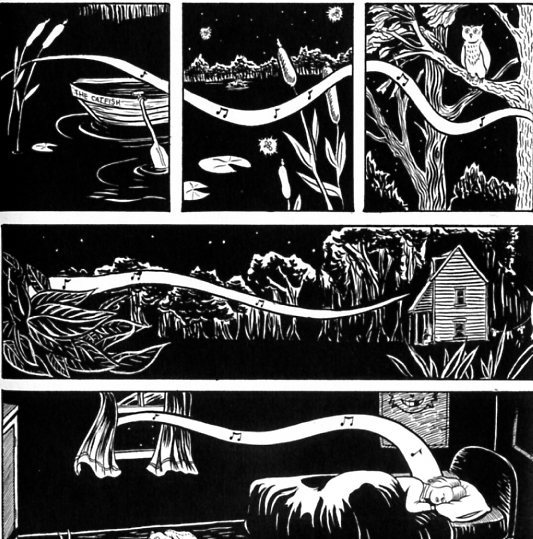

Carré binds these slippages in sequence and reality together by sound – or at least its visual representation. The click of a metronome, the squalling of cats, grandfather’s finger tapping, and most of all the creature’s song, all float through windows and across panel borders in fluid, looping ribbons, knotting together page and space and time. Childhood and adulthood are both bound or drowned in a single voice, each watching the other through a surface of dark water. Lagoon isn’t so much a coming of age as a coming and going. The girl dreams of the creature she will never see; the mother drifts downward towards a childhood that is gone. Where they meet, is, perhaps, in gothic fantasy: a girl dreams she’s a woman dreaming she’s a girl, and wakes not knowing which is which, or where the monster is.

Where was the fucking ending? GAAAAAHHHHHpiss me off!

If you don’t have an ending, at least say you don’t have an ending!

???? What are you talking about Mark. The last sentence is above the picture.

It seemed like a fairly full stop to me — what else were you looking for?

Oh, not you. The Lagoon. Every time I think about it it makes me mad again.

That’s so funny…I thought the end was lovely.

It’s not trying to be a prose narrative at all, is maybe your problem. It’s like getting angry at Rilke for not providing narrative closure. The Lagoon’s a dream, not a story.

I hated it more than anything, ever. It WAS a narrative up ’till the end – an extremely clear and fairly detailed one. You can’t do 78 pages of narrative and then decide to be a dream for two pages.

It befuddles me that you feel that there was a clear story there. I very much read it as a poem/dream from beginning to end. But mileage will differ, I suppose….

I can kinda see that – But I definitely saw a relationship-based narrative component to the book, even if you consider all the “monster” parts a dream.

It’s definitely using narrative; the time jumps for example require some sense of narrative to make them effective. But I think using narrative, or having a narrative component, is different than actually being a narrative that requires or suggests the kind of closure or ending you seem to have wanted from the book….

I like endings. I am pro-endings. I saw it more as Graphic Fiction than an art comic.

But I guess I liked everything else. The visuals of music as this inter-panular pervasive force were cool.