Asterios Polyp takes an impeccable sense of visual design and layer upon layer of sophisticated allusion to tell a clichéd, tedious, poorly imagined, ruthlessly uninsightful story. It’s like listening to a musically brilliant opera with the book taken directly from a TV movie of the week, or (to take an analogy perhaps closer to my heart) listening to classic Slayer perform a John Updike novel. You can’t but be impressed by the technical skill and control…but it’s hard not to feel that, skill and control notwithstanding, a person who could expend such time, energy, and passion on such vapid idiocy must be, on some level, a fool.

Of course, with a book this intricate and complicated, it’s always possible that the person who doesn’t get it is the fool. I know what I’m supposed to do with this book; I’m supposed to start googling all the names that have flagrant double-meanings; I’m supposed to read and reread looking for connections, following up secret paths. How is the theme of doubling worked through the book? How do the different styles link to different moods and themes? Why does the guy who pokes out Asterios’ eyes at the end seem to recognize him? When exactly did Asterios give up smoking and what does it mean?

I figured out a few of these answers despite myself — but, man, overall, I so don’t care. And I don’t care because, with all the twists and turns and clever games and beautiful drawings, this is, at bottom, a character study, and Mazzucchelli’s characters are all as tediously second-hand and tired as his designs are inventive and new. Asterios Polyp, the character, walks out of the massive towering edifice of literary fiction via rote Hollywoodization, and he’s as utterly devoid of interest as he was the first thousand times I saw him. Hey, look, it’s a Successful Professor Whose Intellectualism Has Disconnected Him From Life. And there’s his younger, also brilliant, but more tentative wife — and…wait! He’s driving her away through his callous self-absorption! Didn’t see that coming. And now he’s undertaking a spiritual journey which involves interacting with common people and/or ethnic minorities! And, look, he learns his lesson and spiritual renewal is his — and happy, happy love! Yay! The end. And if I want to see it all happen again, I can just rent The World According to Garp.

I don’t know. Here are a couple of moments of emblematic shittiness.

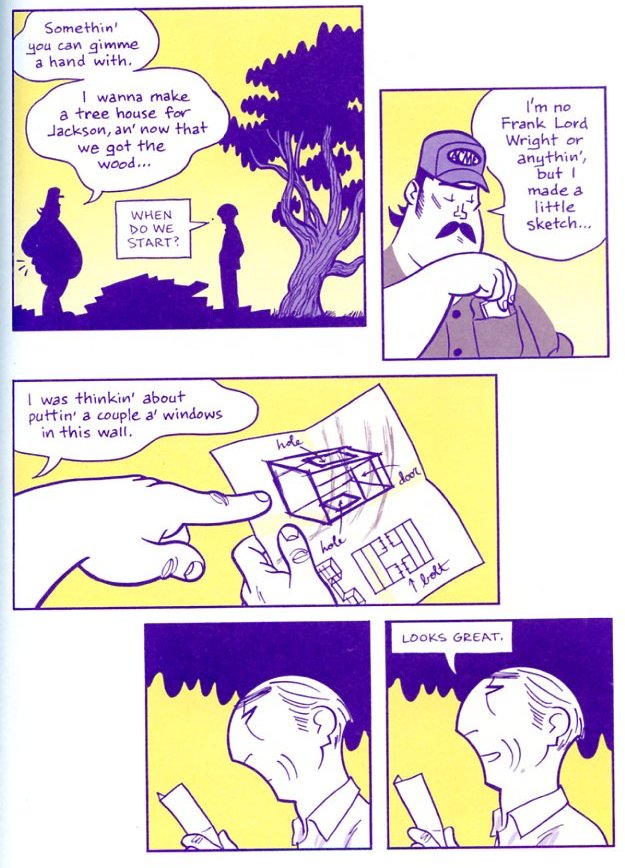

That’s our hero, Asterios Polyp, the great snobbish architect who has never built a house, committing himself to help his working-class boss and landlord build a rickety little treehouse for said boss’ adorable son. Can you savor the gentle irony? Do you feel the tear in your eye? Can you hear the inspirational music from various Kevin Costner vehicles welling up to play over the heartwarming montage?

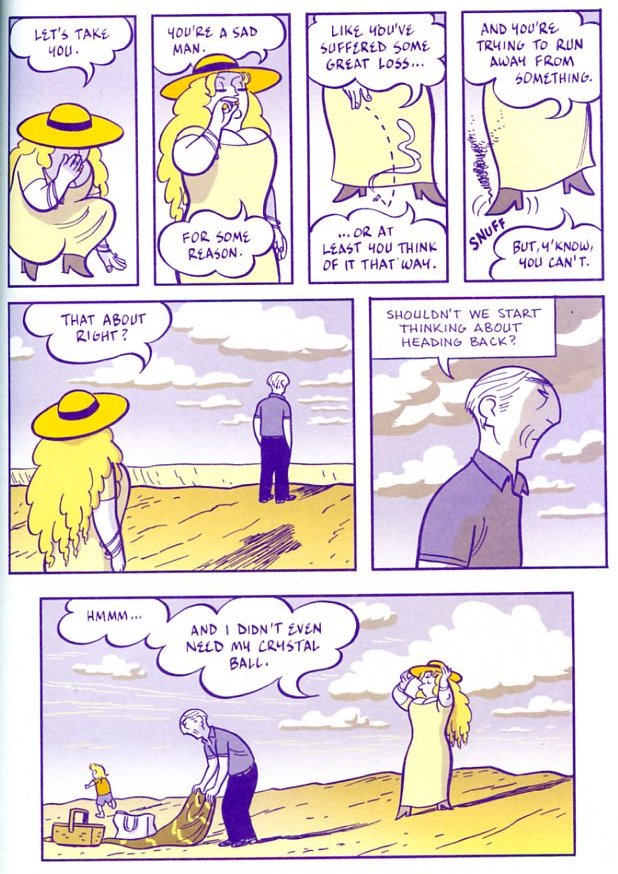

Here’s the boss’ wife, who is into new age nonsense (which we shouldn’t just reject as nonsense because we’ve already been informed that too much rationality is bad bad bad) looking deep into Asterios’ soul and seeing the wounded longing therein. It’s like his heart is just like that giant hole in the ground they looked at a few pages ago, which is a big ironic irony, because Asterios’ heart isn’t a hole at all. How could it be when he got it spackled over with moments of trenchant revelation borrowed from every half-assed rom-com script of the past quarter century?

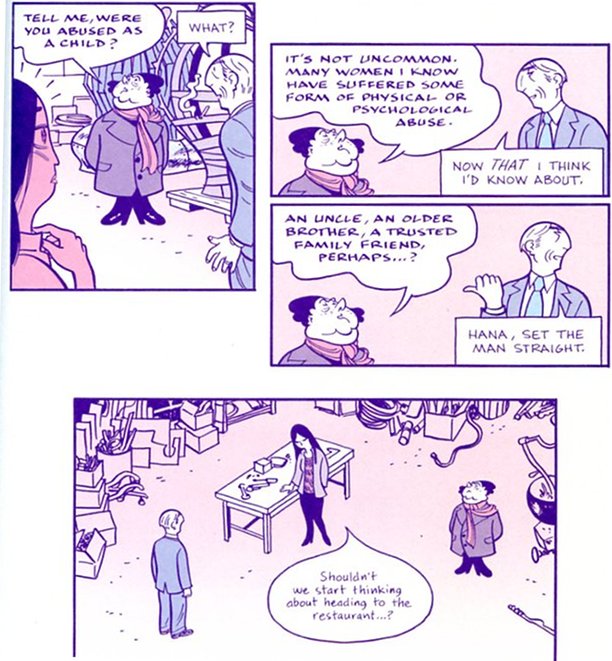

Look! His wife is the victim of sexual abuse! That adds emotional depth, doesn’t it! Hey, this book is really about something, damn it!

Matthias Wivel suggests that the story appears “reductive” because Mazzucchelli leaves out most of the connections; we don’t learn more about Hana and Asterios’ relationship because the point is that we’re to fill it in ourselves — figuring out the spaces in the architectual plan for ourselves. It’s a generous reading, and may well be what Mazzucchelli had in mind. The problem is that the plot and characters he’s given us — the frame in which we are to perceive the spaces — have little of genius, or even elegance. Instead, what he has erected is made out of shoddy, second-hand, thoroughly pissed upon fragments of mediocre pop culture detritus. Which is to say, the problem I have with Asterios Polyp is not, alas, that Mazzucchelli doesn’t give me enough. He gives me plenty.

__________________

This is the first post in a roundtable on Asterios Polyp. Derik Badman will weigh in tomorrow,(He’s now done so) and we’ll have various other Utilitarians and guests posting through next Monday.

Update: You can read the whole roundtable so far here.

So I take it your weren’t the one who picked this book as the roundtable topic?

I think Suat suggested it first, actually. I was on board, though! I saw a lot of people recommend it, so I was interested to see what I thought.

Well I mostly agree with you about the characters and story. But, as we’ll see tomorrow, there are plenty of other things in the book that hold my attention and interest.

I suspect Derik and I will be on the same page with this one. Noah, I agree with you on the overall shallowness of the characters and situations, but aren’t you interested in the formal innovations at all? And shouldn’t those weighty formal innovations carry some additional sway in a book whose protagonist is a formally-innovative architect who has an uneasy relationship with functionality? It seems like a pretty direct line to me. That being said, the ending (such as it is) feels like an inexplicable cop-out.

Hey Sean. I actually like the art as art quite a bit; the book is lovely to look at, and I got a lot more enjoyment out of this than I do out of Dan Clowes or even (recently) Chris Ware. If I have to have stupid, boring comics, I would prefer that they were stupid, boring comics with brilliant art.

On the other hand…a lot of the formal innovations seem like gimmickry to me. The form-and-function dichotomy around architecture for example — yes it’s clever, yes I get it. I can admire the cleverness, and cleverness is certainly better than nothing. But the content is so rote and frankly so dumb that the formal shenanigans never take hold for me; all the creativity has been lavished on the formal games, and none on actually thinking about what is being said. (For example, yes, there’s a tricky relationship between form and function. But most of what comes out of that dichotomy is simply a fairly simplistic moral (you should be more engaged with life!) which is actually (and I don’t think intentionally) undercut by the hollowness of the actual content on display.))

It’s just really difficult for me to be engaged with a work where (a) the content is presented as having weight, and (b) the content is so thoroughly stupid.

If Mazzucchelli actually had something to say, or if he just went all out pulp and presented the content as clearly fluffy or unimportant, I’d be much more on board. But he very clearly sets up the story as something we’re supposed to take seriously…and I can’t do that. As a result I can look at the formal beauty and appreciate it, but as soon as I start to read it starts to look like a gilded palace erected to do honor to a turd.

I don’t know…as an example, in the final scene of reconciliation between Asterios and Hana, Mazzucchelli has their speech bubbles intertwine. The intertwined speech bubbles are lovely from a design perspective, and it’s obviously thematically relevant. But it also, to me, seems over-obvious and over-determined. Form follows content, but the content is banal (they still love each other!) and that ends up making the form look glib.

Noah, you bring up Hollywood in your review and it got me thinking that your problems with Asterios Polyp are the exact same problems I had with James Cameron’s Avatar: the brilliant design work and special effects work couldn’t make up for a story was really, really stupid.

That being said, I liked Asterios Polyp a whole lot. I have the sense that Mazzucchelli isn’t so much interested in telling a story as providing a primer on how comics can be innovative in using illustration to express moods and ideas. I was having such a good time taking in the images, I never got worked up over the fact that the ideas and characters may not have been all that original.

I did get excited about a future where other creators with better stories adapt the techniques shown off in this book. So many comics today are very literal, relying on text to express concepts when the art falls short. I’ve become enamored with the idea of Concrete getting the Asterios Polyp treatment

It’s certainly exciting to think about Mazzucchelli collaborating with someone who actually had a story to tell, or someone else using these techniques for good. Will it happen though? I guess we’ll have to wait and see…

My friend and fellow cartoonist Carl Nelson (http://blog.carlnelsoncomics.com/) is the one that pushed APolyp on me in the first place, and he hyped it to me as a sort of test-drive of some of the principles and theories set out in some of the later chapters in Understanding Comics. When I brought it back to him and complained about the story, and the ending in particular, there was a break down in the conversation because of these two different ways of approaching a text. I suppose part of the problem is that, like the medium of movies, comics have had very few unqualified masterpieces.

With movies it seems fairly straight forward why this is the case- the tremendous expense that is required to work in the medium, and the enormous amount of skilled staff that need to be in place to make everything come together. I suppose the corollary problems with comics would be the general perception of the public of the worth of the medium, the potential audience for other media competing for artists and writers, and the amount of different skills a successful cartoonist must master in order to even be competent in her chosen field.

The infamous Comics Journal top 100 list is a great example of all the compromises involved in analyzing work from the past of North American comics, anyway. How many of those comics could be considered unqualified masterpieces, and how many of them are interesting works either formally or in their content, that could be mined for use by artists in the future?

I would say I enjoyed Asterios Polyp, even though I agree with Noah’s criticisms of it for the most part.

To me Asterios Polyp reads like one of those “sunny day at the beach” page turners. Yeah, it has some neat formal tricks. Yeah, it a few neat things about art and whatnot. But I just look at them and say “interesting point” and then quickly move on. The book just zips along because of Mazzuchelli’s breezy, spacious layouts and storytelling. Granted, the story really is pretty much typical male middle-aged navel gazing (which reminded me of the film Synedoche, New York, which I actually hated unlike Polyp)

I realize that Noah is reacting to the self-important posturing of Asterios Polyp, and I can’t deny that it’s there and it looms large. But I honestly didn’t dwell on that aspect of Polyp.

There has been a trend of late wherein many popular alt-comic artists have begun to openly dissect the form they’re working in, even placing formal innovation over thematic or story content. Many younger artists, like Dash Shaw, have jumped onto the “self-conscious COMIXXX” bandwagon as well. I guess inevitably it had to happen. I’m not against explorations of form…after all, I’m looking forward to the Bushmiller Nancy reprints, with its barrage of calculated brain-dead jokes and mathematically precise compositions. Still, it’ll be interesting to see where this trend goes.

Part of me feels that by keeping their emphasis strictly on talking about COMICS, they are able to remain within a safe bubble where they don’t have to reveal anything particular about themselves or what their opinions on issues outside of comics are. So instead of using comics as a vehicle for their thoughts and ideas about the world around them (and possibly opening themselves up to personal criticism) they can stay within their bubble of talking strictly about the medium they’re working within, and just take the impersonal potshots we throw at them about their vanilla-flavoured stories.

I have to say I’m a little surprised that everyone seems to more or less be conceding my point re: content. I’m curious if anyone in the roundtable is going to defend the story as a story…

Magic Rednecks are the new Magic Negroes.

Dirk: That’s too funny.

Sean: A good point in re compromised classics. I can easily name tons of unqualified great novels (ones that I think are great and have no qualms about it), but I can’t easily get even close with comics. There’s always the “well the story is great, but look at the crappy art” or “formally, a work of genius, but oh the story is so stupid.” Exceptions, off teht op of my head (and glancing over at the shelves of comics)… Jaime Hernandez’s neverending Locas series, swaths of John Porcellino’s work… hmm… well, that’s a game for another time…

Dirk, if only it were new. Magic rednecks have a long and stupid pedigree, I’m pretty sure.

Derik, I think Peanuts is pretty solid.

As I believe I’ve mentioned before, it’s problematic to seperate “story” and “art”, or form and content. In AP, the form is completely integral to what the work is about. I won’t spend too much time here arguing the point, but merely point to my essay on the book, which Noah kindly linked in his piece. I’m not crazy about AP, but I believe calling Mazzucchelli a “fool” and the content “thoroughly stupid” is grossly reductive.

“It’s certainly exciting to think about Mazzucchelli collaborating with someone who actually had a story to tell, or someone else using these techniques for good. Will it happen though? I guess we’ll have to wait and see…”

Already happened. The result, Paul Karasik’s and his adaptation of Auster’s City of Glass is quite marvelous. Oh, and Batman: Year One ain’t bad either…

Noah said-

>I think Peanuts is pretty solid.

Peanuts is the perfect example of the compromised masterpiece, both because of its excellence and all the back-bending required for a sensible person to read it.

Imagine some theoretical potential reader of Peanuts that has never been exposed to the comic before, and is additionally unfamiliar with the prescribed limitations of the daily newspaper script. Besides the obvious problem of “what volume/era of Peanuts do I read first?” there’s a whole series of potential problems that an intelligent reader would have to overlook, that we all do so because of our familiarity with the compromises and capitulations that have attended our medium from the beginning.

Questions upon first reading “Peanuts” (once someone has come along and explained to me which volumes of “Peanuts” are actually considered “Peanuts”, in their estimation, anyway)-

1. When the hell does this take place? How come the characters make all these contemporary references to different time periods?

2. Why do some people get older, and once they’ve hit that point they all stay the same age forever? Why don’t they seem to remember events from year to year?

3. When they do manage to remember recent events, how come they have to repeat key information every few panels?

4. When is something of lasting consequence, some type of long-term plot or arc ever going to occur? Isn’t there an ending to this damned thing? Maybe they’re all in purgatory or something, awaiting their final judgement…

Now, obviously, I see all the worthwhile things in Peanuts, and several of the Complete P volumes adorn my bookshelf. But how can any genuine masterpiece of any medium have so many attendant qualifications?

Sean, I really have to disagree. Peanuts is incredibly accessible — really, even kids can pick it up and get it instantly. Many individual strips are among the greatest art ever created, in any medium, I firmly believe. Schulz wrote beautiful, bizarre koans. Did the strip vary in quality over time? Sure. But as a whole it’s an amazing artistic achievement. I don’t think it needs to be apologized for on any level.

To just respond to your first point — a specific place, time, or setting simply hasn’t been a requisite for any type of art since modernism at least. This goes to most of your other points too. You could level almost all of them against Beckett’s work for example. There’s just no reason any of that needs to matter at all in evaluating a work’s quality.

Matthias, I also think separating form and content is really problematic. That’s why I can’t take Asterios Polyp seriously — and why I can’t help but think it’s kind of dumb.

BUT! I’ll look forward to having you explain at greater length why I am rash and misguided!

Noah-

I agree with all the positive things you’ve said about Peanuts, including its immediate accessibility. I guess I should have amended that to “all the back-bending required to read it as a coherent narrative.” Seeing various volumes as collections of haiku is very sensible. The comparison to Beckett isn’t very apt for me, though, because of all the references to the real world, all the things that pin it down to very specific times and places. And, of course, over the long term, looking at many many many strips, in the format it is now presented, those references smear over time, making the setting for these haiku, such as it is, some type of meta-time that doesn’t fit the specificity of the drawing or the cultural references.

Anyway, equally silly to my argument might be the silliness of having collections of haiku appear on the same “best of” lists as short story collections, anthologies and more long-form narrative fiction. Maybe the real problem with the comics canon, such as it is, is the sparseness of it means that works of radically different forms and intents compete with each other directly for critical recognition all in the same venues. It’s the equivalent of analyzing who the best painter is- Bosch, Hokusai or Schnabel.

I also want to hear Matthias’ explanation of why Noah is rash and misguided! But in the meanwhile…

Matthias, I’m trying to unpack your objection to the “form/content” business because it comes up a lot: I don’t interpret the phrase “separating art from story” to mean the same thing as “separating form from content” — which is how I read that “or form from content” phrase at the end of your first sentence.

Here is an axiom, stated for clarity: story and art each have both form and content; story and art each participate in generating both narrative and metanarrative meaning.

I took Noah’s point to be that the sophistication of the narrative wasn’t as high as the sophistication of the metanarrative, and that this imbalance made the work overall weaker. I didn’t take this to be a distinction among form/content/art/story since all four contribute narratively and metanarratively.

I can’t tell whether you’re saying that it’s sufficient for the metanarrative to be complex and that the narrative doesn’t matter, or whether you’re saying that the narrative is more complex than Noah is acknowledging.

Hope that’s not too convoluted to parse…

Huh. I’m not sure if I was saying that or not, Caro. But the point that story and art both have form and content seems like a really worthwhile one.

I think I was definitely drawing a line (as it were) between the art (which is marvelous) and the writing (which really is not at all.)

I would say that in general the form/content one is actually something I see as a problem in AP as well. That is, the art generally has narrative/thematic points to make (many of which Derik will talk about tomorrow I think.) A lot of those points seem fairly simplistic to me. The intertwining speech bubbles I mentioned above, for example; the form is lovely, the content of that choice is banal.

What are you thinking of as metanarrative exactly, Caro? Maybe defining terms would help somewhat.

I will say, in reference to Matthias’ essay, that there’s some point to be made that the limits of the books emotional range are supposed to be tied to the formal intensity — that is, Asterios is obsessed with form and emotionally hollow, and you could say, well, Asterios is like that, the book is like that, the form and the content go together. The problem, for me, is that (a) the idea that perfect form is distancing and chilly is cliched and simplistic; and (b) using an academic to attach that point to is cliched and simplistic to the point of stupidity. The form and content fit together, but what that fit adds up to (the metanarrative?) is little more sophisticated than, say, the portrayal of academics on the television show Bones. It’s maybe even less sophisticated in some ways, since Bones at least switches the gender polarities and occasionally marginally complicates the idea of academic-detached-from-emotions.

So yeah, when I see a book this technically accomplished which is nonetheless in important ways less sophisticated in its examination of its central themes than a mid-level TV cop drama — it’s hard to know what to do with that except throw up your hands.

For an actual great work of art that deals with the core issues in Asterios Polyp, I think I’d go for Pygmalion. LIke AP, there’s a contrast between the man of genius representing reason and method and a woman representing feeling and connection. Shaw does a much better job of complicating that binary though, I think. Both Henry and Eliza have lessons to learn — or possibly not, it sort of depends. They definitely both get to be the protagonists, though, and to be struggling to assimilate each other’s positions and ideas, whereas Polyp really just gives us AP’s perspective, and Hanna functions more or less entirely as his object lesson/goal/reward. Matthias might say that this is a function of the modernist limiting of perspective — but the perspective we get is a rote, boring one we’ve seen hundreds of times before. Whatever its formal justification, I don’t see it as aesthetically effective.

Metanarrative’s not a great word for what I mean ’cause it’s got those Lyotardian overtones…I guess I mean metafictional narrative? In this case at least…

The distinction I’m trying to get at is between an “on the surface” narrative — story, plot, characterization, simple metaphor, all that stuff — and the “meta-narrative” that you can construct in formally sophisticated books from “reading” the formal elements of the work (not intended to imply any particular strategy for reading that form.)

I mean it in a very broad sense — meta-narrative doesn’t have to be metafictional, although I think this one is — my point would hold as well for something like a traditional allegory: the story of Christian’s journey to the Celestial City in Pilgrim’s Progress is narrative, and the allegorical meaning of that journey as the well-lived Christian life is a “meta-narrative.”

I’m quite sympathetic to the idea that it’s ok for a book to be all meta-narrative and not much narrative: Godard’s Alphaville is my favorite movie and I think it’s a decent example of that. But the surface narrative of A-Polyp isn’t quite that open. Hence my question to Matthias: whether he thinks there’s more to the surface narrative than you do, or whether he just thinks it doesn’t matter that there isn’t.

I wasn’t nearly so bothered by the examples brought up so far as by the rock singer/musician who’s devoted to Maoist principles and babbling about liberating the working class. I’m like, what? Does any twenty-something walk around America these days spouting Communist dogma? Pretty ridiculous.

Thanks, Caro, for calling me on that distinction. Of course, the story/art dichotomy that comes up so often in discussions of comics can’t be equated directly with form/content, but it seems to me often to be what people are talking about when they say “the art is lovely, but the story sucks”.

As for AP, my point is that the ‘surface narrative’ has more going for it than is immediately noticeable, and that it achieves this negatively, by leaving out stuff one might expect to see there.

I agree with Noah that the book is limited by its protagonist, although while he might be clichéed were he rendered in prose, the paper architecture by which we know him is quite beautiful and compelling.

Caro, you should click through the link to Matthias’ essay if you haven’t already; he explains what he’s talking about in greater detail there.

Noah: I’m with you on Peanuts (those are in a different room, so they didn’t jump out at me on the shelf).

Sean: I think your feelings of the lack of a coherent narrative in Peanuts, is more about trying to make it something it is not. Like applying the standards of a novel to something that is clearly not.

I really do enjoy the anticipation of reading your take on things. However, to often I walk away thinking I am the intellectual equivalent of a Banana Slug (the best mascot by the way). In the case of Asterios Polyp “of course, with a book this intricate and complicated, it’s always possible that the person who doesn’t get it is the fool.” And I got it, or at least I thought I did before reading this. Yeah ME.

Oh dear. Well, if it’s any comfort, lots of people think I don’t know what I’m talking about at all, about anything. No reason to doubt yourself when so many feel you should be doubting me instead!

Wow, this is one of the times I actually agree with Noah–except that I didn’t care for the art that much either. (Maybe Noah actually likes it, but “the story sucks though the art is wonderful” seems to be one of those things people say who, because of the team-comics spirit, are embarrassed to say they found the book a letdown all around.)

Mathias–it strikes me that the *real* separation of form and content is performed by those people who (begrudgingly, perhaps) admit the shortcomings of the story, but claim it still is a masterpiece because “you cannot separate form and content,” and then go on to argue that the form is so great that it redeems the content. I guess I’m just tired of hearing this argument on behalf of all the near-(intended)-masterpieces of the comics medium; sorry, if one part of the edifice is weak, the entire building crumbles. If the foundations are not sound, you cannot rescue it by saying “the building is of a piece, and just look at the beautiful use of the orders and the magnificent scrollwork.”

Caro–I think the distinction you’re trying to go for is closer to syuzhet and fabula (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fabula_and_sujet).

No; I really liked the art. Some of the loveliest design work I’ve seen in Western comics, I think.

I’m pleased to have been accused of being on Team Comix though. I think that’s the first time I’ve ever had that particular charge levelled at me.

Ooh, maybe my metaphor ran away from me. Let me try again: If the foundations are not sound, you cannot rescue the building by saying, ” but just look at all the top-notch, innovative engineering on the upper floors.” The building will still crumble.

And, by the way, it’s not that I hated the art itself, I just found it rather uninteresting and the formal displays empty in the absence of a story to prop them up. I probably wouldn’t have minded it if the story had been better. I see all the point that people like Derik or Domingos have raised in favor of the book, but they seem like just tokens, shibboleths on which we focus in lieu of (or to make up for) having a real aesthetic experience.

Noah–a) there was no “accusation,” and b) I would usually not imagine that was your motivation; I was just pointing out the similarity. I said, “maybe” you really like the artwork. I guess you do. Ah, letdowns after letdowns!

“a Successful Professor Whose Intellectualism Has Disconnected Him From Life. … now he’s undertaking a spiritual journey … common people and/or ethnic minorities! … And if I want to see it all happen again, I can just rent The World According to Garp.”

Why Garp? It wasn’t anything like this Polyp book you describe. Also, I liked it.

“… moments of trenchant revelation borrowed from every half-assed rom-com script of the past quarter century?”

Maybe Polyp’s mother died when he was a kid.