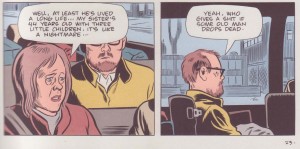

Synopsis with significant spoilers. “Wilson is a big-hearted slob, a lonesome bachelor, a devoted father and husband, an idiot, a sociopath, a delusional blowhard, a delicate flower.” His misanthropic existence is filled with misdirected rage and a search for meaning and connection. His closest companion is his pet dog, Pepper, but his father’s death prompts him to leave her in a quest to find his ex-wife, Pippi, and his daughter, Claire. He finds them both with the aid of a private investigator but this fleeting happiness ends when he is imprisoned for kidnapping his daughter. When he is finally released after a period of 6 years, he discovers that his dog has died. His ex-wife is already dead by her own hand. His one time dog-sitter, Shelley, becomes his only consistent companion. Wilson is briefly reunited with his daughter and discovers that he has a grandson. The connection is short-lived and she will only communicate with him through the distance afforded by an internet connection. The closing page shows him at an uncertain rest while contemplating the fall of raindrops on his window.

Wilson stares out at us from the cover of his book. His eyes are dead in their sockets and enclosed by thick spectacle frames. His shirt is packed into a pair of ill-fitting pants; his cranium over-sized in relation to the rest of his body; his creator’s birth date etched into the pavement slab behind him.

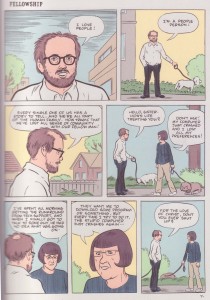

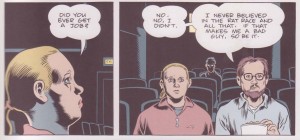

His disjointed urban misanthropy is vintage Clowes made simple and unrelenting, while the structure of his hate recalls the Sunday funnies as filtered through the hands of “Charles Schulz, Mort Walker and E.C. Segar” (Paul Gravett). These choices allow Dan Clowes to acknowledge the foundations of his episodic comic, his first work to be released without prior serialization. Each page represents a single moment of conjunction in Wilson’s life, moments which he almost unfailingly renounces and denigrates. The segmented nature of Wilson encourages us to view the character’s metamorphosis like cuttings from a long running strip: gags are developed upon and refined; the protagonist’s intransigence only partially amenable to change; his epiphany on the final page as strange and enigmatic as the musings of a cartoonist on his final job.

Much has been made of the varying styles Clowes employs throughout Wilson. Sean T. Collins doesn’t feel that “the kaleidoscopic array of styles in which Daniel Clowes drew Wilson says much of anything”, this itself being the “gag”. Jog proposes that it is a “a simulacrum, in that the way us readers see him is broken up page by page so that he’s “as if” spotted by a somewhat different (biased, interested) observer, even in scenes where no observers are actually present.” Ken Parille advises his readers that “the styles of Wilson represent a refusal to participate in the lie of certainty and consistency — in place of such assurance Wilson substitutes a series of beautifully executed styles that give us an honest, and therefore incomplete, portrait of a compelling character.” Tom Spurgeon believes that “the author intends it as commentary on just how difficult it is to “know” a character or more generally get at truth through art.” The latter three commentators would appear to be circling the same essential point, a point which is distilled in Spurgeon’s simplification. What this amounts to in reality is a more diffuse and instinctive approach to the selection of style; a technique which allows Clowes to elaborate on temporal and interpersonal connectedness (one of the main themes of Wilson) as well as the shifting of perceptions.

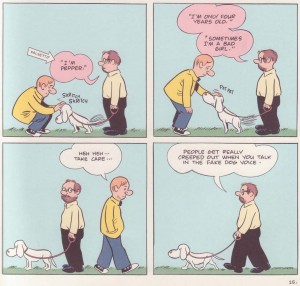

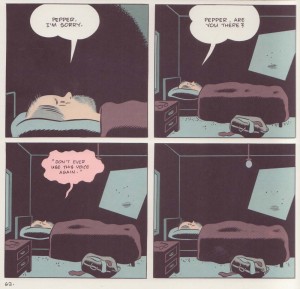

Color unites and amplifies in Wilson. There are the pink balloons which enclose Wilson’s fake dog voice (page 15 and 62)…

… a voice he uses to creep people out and which comes back to haunt him when he ponders the death of his pet later in the book. These moments are clearly meant to be both darkly humorous and ironic in all their displaced meaning.

In another instance, brownish hues (page 14) foreshadow a scene where Wilson sets out to deliver a box of dog shit to his relatives.

Reality, in all its color and detail, can also be a deceptive mask. The jovial and realistically drawn character on the first page (realized with a full palette) who then lets loose with a stinging request to “shut up” in the final panel informs us that surface and substance often have little to do with each other.

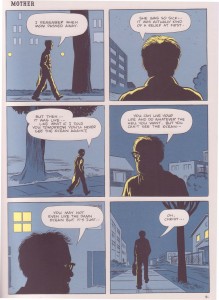

The darkly drawn and silhouetted scenes of Wilson reminiscing about his mother’s death (page 9) drive past exterior appearances into the shadowy depths of his soul.

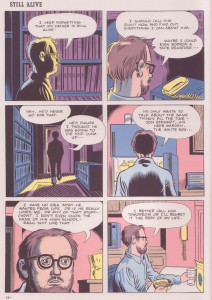

This technique is repeated on page 16 of Wilson where the protagonist traverses the dark corridors of his library while contemplating a call to his father.

The sequence proceeds through the bright light of correct decision before coming to a definitive end in his father’s death (page 19 and 26).

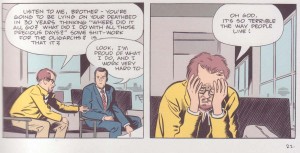

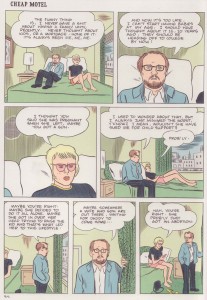

These pages will serve as well as any to show how Clowes connects his narrative through formal mechanisms. Each moment in which Wilson confronts his father’s (and his own) mortality is laid out in the primary style seen on the very first page of this book. This includes his unconscious desperation when he talks up a traveler at the airport (page 21)…

….as well as his indignant confession to some strangers on an airport shuttle (page 23).

This stream of stylistic consistency is only interrupted by two moments of unbridled fatuousness (an encounter on an airplane and another with his father’s nurse) where his despondency is temporarily alleviated.

There are other instances where style is used as a linking device across the leaves of this short book. Page 17 (“Fat Chicks”) has Wilson eyeing a slightly rotund, blonde female while sitting at a cafe.

The page is inscribed in a style which is reiterated (less the cross hatching on Wilson’s nose) on page 36 where he is seen having a nightcap with Pippi, his blonde ex-wife, for the first time in 16 years.

The normal looking individuals who inhabit the more realistically drawn page which follows (page 37) militates against the sense of body dysmorphia found in the earlier passages.

Wilson is possessed by fantasies about Pippi. His encounter with a blonde prostitute (page 33) is a moment of self-deception as is his habitual insistence that his wife once indulged in illegal pharmaceuticals (a point she vehemently rejects).

The thin, blonde working girl becomes a substitute for some longed for interaction and is met on the opposite page (page 34; drawn in a similar style so as invite comparison) by the reality of a slightly overweight and depressive waitress, the ceiling lamps acting as stray and enigmatic thought bubbles. Of course, such illusions have a habit of taking on a life of their own in Wilson. When confronted, Pippi never actually denies a life on the streets and is later found to have a strange mark of ownership on her back. She later dies from a drug overdose in sympathy with Wilson’s earlier accusations.

Paul Gravett has pointed to the symbolic use of water in Wilson but its presence bears repeating as well as elaboration. Characters can be found communicating over cups of coffee, copious amounts of tears and various large bodies of water throughout Clowes’ book. Of particular note are the structural similarities of 3 pages. Page 12 has Wilson staring out at the ocean, an activity which his parents used to engage in for hours when he was a kid. The seaside is vibrantly colored, his solitude interrupted only by some graffiti scrawled on the walls of the pier.

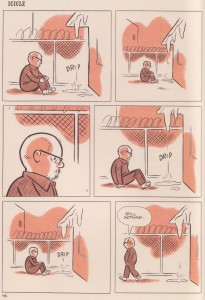

The prison yard on page 58 is spare and of single pigmentation, a counterpoint to his zen-like meditation on the slow drip of a melting icicle . There are six panels here and they represent the six long and empty years Wilson spends in prison.

The final page of Clowes’ work brings muted hues and, perhaps, some unhindered contemplation and enlightenment. The colors recall those used in the earlier scene in prison, with water in the form of rainfall, seen and heard against a firmly shut window.

The key to Clowes’ hydrophilic conundrum can be found in Wilson’s words (on page 12), the gravity of which are defused by a curt kiss-off line:

“Mom and dad used to sit for hours staring out at the lake when I was a kid. I didn’t really get what they were looking at, but it seemed to give them some kind of spiritual replenishment. I guess maybe they were trying to connect with something bigger, something vast and everlasting…Or maybe it’s more complicated than that. Maybe it’s something about the chemical make-up of water, or the connectedness of all things…I feel like if I sit here long enough, it will come to me. I feel like I’m on the verge of a profound personal breakthrough.” (emphasis mine)

The words bring to mind an earlier scene in which Wilson compares the loss of his mother to never being able to see the ocean again. His mistake lies in misconstruing the virtues of companionship for those of a colorless liquid.

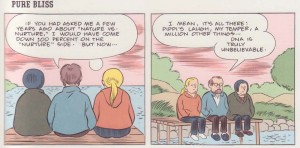

The scene on page 51 (titled “Pure Bliss”) is a re-enactment of his parents’ inclinations cut short by the revelation that Wilson’s daughter has been taken against her will (hence her weeping fit on page 44).

It suggests that any metaphysical comprehension on Wilson’s part is illusory; a kind of spiritual mumbo jumbo and a subset of his self-delusion which may in fact be all that is concrete in his life.

Each turn of a page brings meaning to previously obscure imagery. It is only upon seeing Wilson in prison that we realize that a bright light in the penultimate panel of page 53 signifies the arrival of the police.

Only upon further reflection do we see the empty swimming pool on pg 52 (the more truthful absence of water) as a sign of things to come.

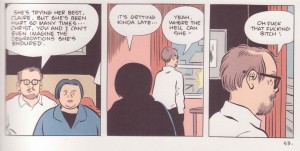

Wilson is released from prison only to discover that the only living thing which he cared for unreservedly (his dog, Pepper) has since passed away. Pepper is his surrogate child and the dog’s sitter, Shelley, a kind of surrogate wife. His grandson (revealed by his daughter in the closing pages of the comic) is a new life which brings new hope for kinship. Even the nameless stranger who barely tolerates him while tapping on his laptop (on page 11, 65 and 76) closes his screen to look at him for the first time in years.

Before it all ends, there’s a loud summation of everything that has gone on before, a cacophonous foreboding of what is to come on the final page of Wilson:

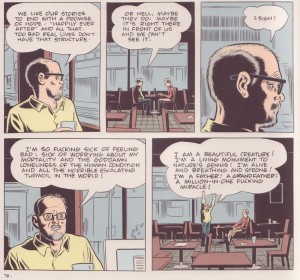

“We like our stories to end with a promise of hope. “Happily ever after” and all that. Too bad real lives don’t have that structure. Or hell, maybe they do. Maybe it’s right there in front of us and we can’t see it. I’m so fucking sick of feeling bad; sick of worrying about my mortality and the goddamn loneliness of the human condition…”

Wilson’s cry of freedom which closes this page (“I am a beautiful creature!…A million-in-one fucking miracle!”) ….

…is lodged in the space normally reserved for the punch line and maybe that’s all there is to it, a moment of incautious and ludicrous hope. It is left to the reader to decide whether Wilson’s final moment with us is an act of God on the part of the author or merely an act of desperation; a futile desire to see meaning where there is none.

***

Further Reading:

(1) A discussion of Wilson at The Comics Journal message board

(2) A symposium on Wilson at The Savage Critics. Probably the most extensive discussion of Wilson available online at this point in time. Coming up for debate are issues concerning reader identification, the dichotomy between family and friends, and the effectiveness of the characterization, stylization and denouement.

I’ve avoided any value judgments in the above review but have more sympathy (for somewhat different reasons) with the cautious or plainly negative views expressed by Jared Gardner, Jog and Douglas Wolk, than those opined by Sean T. Collins, Paul Gravett, Brad Mackay, Ken Parille, Tom Spurgeon, Tucker Stone and Glen Weldon (who are generally enthusiastic).

Wilson is skillful in means but lacks something in its substance, perceptions and emotional resonance. The book may be best appreciated as a kind of cultivated entertainment, humorous in parts but one which is largely empty beneath its bag of tricks.

As is made clear in the article above, I don’t completely agree with Wolk when he says that the stylistic changes are simply a “display of mastery on Clowes’ part rather than particularly like an additional layer of meaning added to specific scenes” but there is a germ of truth in his suggestion that “all the stylistic choices Clowes makes here are within a distinct, limited range of visual style.” This may be a purposeful decision and not one limited by his skills as an artist.

It is easy to see Tucker Stone’s point when he writes that his “immediate response to [Wilson was] that [he] thought that Clowes was commenting on other comics, on his contemporaries.” Of these, Ivan Brunetti is more violent and self-lacerating, Adrian Tomine more grounded in certain kind of reality, Chris Ware more frequently emotionally satisfying and clever as a formalist. Even the younger Clowes seems more sophisticated in his rancor. Clowes’ qualities as a writer and cartoonist (more literary, less poetic) are ill-suited to the pared down comedy of Wilson, a deficit which throws Schulz’s achievements on Peanuts into sharp relief. Tucker is kinder in his final assessment suggesting that much of the comic consists of Clowes’ gentle ribbing or referencing of his contemporaries. He does not, however, work up enough fire to submit that Wilson is a full on satire and an attack on the sub-genre as a whole, mainly because there is nothing in Wilson which suggests as such.

(3) An interview with Dan Clowes at The Star.com

“But the idea of actually committing to doing an entire book, and the thought of how long I knew that would take me, that was a hurdle to get over. But once I got going it went much more quickly and pleasantly than I’d feared. I see no reason at this point anymore to do things in the serial format. It just doesn’t make sense anymore, the way the world works these days.”

“He’s certainly written from within, but he’s not at all like me in most ways. I’m not the kind of person who can come up to a person and sit at a table and start talking. Wilson is completely uncensored. He has no self-regulating mechanism. He is like a walking id who does not filter himself to make himself more palatable.”

(4) An interview with Dan Clowes at The Boston Phoenix

“QN: Why the six-panel format? Was it a challenge, each page requiring a punch line?

I’d just finished reading the biography of Charles Schulz. And there’s a quote from Schulz saying, “A professional cartoonist can take five minutes and cobble together a completely workable idea for a comic strip, where nobody would even notice that it took him five minutes. That’s what it means to be a professional.” So I sat down with my sketchbook, and I just started doodling comic strips about this guy I’d never thought of a minute before that — who turned out to be Wilson. I tried to do it sort of like a Peanuts strip, where they had a certain rhythm and a punch line.”

(5) An interview at the DCist

“When I actually sat down to write it, I tried to devise a master style that would work for the entire book and I kept veering between doing really cartoon-y styles and then going to a much more realistic style, and trying out all these different methods. And as I was doing that I realized that that was the only way to do the entire book. There was no one style that made sense for this book. It would have to be this kind of mosaic approach where you’re seeing kind of different facets of this guy on different days, and kind of separating each strip into its own different universe that’s not necessarily related to the others in sequence.” (emphasis mine)

This looks really indescribably horrible. The alt comics mafia’s apparently unquenchable desire to turn Charles Schulz into a boring zombie automaton spitting out reams of generic literary fiction — why? What did he ever do to them?

Thanks for the Peanuts strip, though. Nice to be reminded that even with Clowes’ 50,000 styles of pure genius, I’d still much rather look at the bricks in Charles Schulz’s wall.

“This looks really indescribably horrible.”

Yeah, it’s pretty bad, but mainly because it’s so dull.

No doubt about it. If you didn’t like Clowes before, this book certainly won’t change your mind. It’s one of his weakest books. Plotwise, somewhat derivative and almost ripe for a quirky movie adaptation. On the other hand, as noted above, the majority of critics out there seem to like it. If there was a metacritc score for comics, “Wilson” would probably get something like 60-70%. I would, however, like to read someone make a good case for its excellence as a story.

Clowes is pretty untouchable though; I think people give him a lot of benefit of the doubt. (Charles excepted!) I mean, Wilson clearly doesn’t suck as bad as shadow of no towers, and a lot of people were willing to give that a pass. Once you reach a certain level, you get a fair bit of leeway.

Which is to say — if he’s getting 60-70%, that’s pretty shitty, actually. I doubt he could get much lower than that without doing something really apocalyptically bad.

I don’t think Clowes is that untouchable. At least, he’s not as highly venerated as Spiegelman. On the other hand, there’s definitely a sense of expectation whenever a new book arrives from one of the old guard. I see it as a marker of how comics readers have been “trained” to expect great things from the alternative cartoonists who made their bones during the late 80s and early 90s; the group of guys/gals who helped in the initial pull away from superheroes during the 80s boom. Jared Gardner’s review is most honest about addressing this. In many ways, consumers have learned to make do with less when it comes to comics. Our expectations would be ameliorated if reader’s viewed “Wilson” more as an interlude in Clowes’ career, a half-formed sketchbook idea which became a book (Seth’s Wimbledon Green was better in that sense). The publicity drive doesn’t seem to allow for this though.

Ah, well, it happens everywhere, not just comics….

I don’t want to read too much into it, and I’m sure Ken Parille honestly liked the book, but the fact that he (to my mind, the most thoughtful Clowes critic out there) concerns himself almost exclusively with the varied style of the book (hardly anything new in the artist’s oeuvre) suggests that the book ain’t saying much. Bottom-line for me: the book was supposed to be funny, but wasn’t. The misanthropy was aenh, the humor was so-so, and the social commentary was by rote. I’ve seen it all before, done much better/more radically (e.g., Brunetti). I guess he was gong for sympathetic misanthropy, but I couldn’t help but think how much better Miike’s Visitor Q is in just about every way at covering similar themes. Clowes is pushing the envelope when he needs freight shipping.

Hmm, Ken Parille does tend to favor close readings of narrative and technique as opposed to content on his blog. That just seems to be the agenda he’s set for his writing on Blog Flume. I don’t think it’s particular to “Wilson”.

Still, almost no arguments with your “bottom-line”. I’ll have to reread some of Clowes older work to be absolutely certain but “Wilson” seems too much like a stripped down retread of his usual schtick. “Visitor Q” (or Miike in general) seems too far to one extreme for Clowes to even consider.

I have read nothing in the many reviews and discussions to make me want to buy this.

And thank you Suat for satisfying my interest in the formalistic aspect of the book (the stylistic variaion), which was the one thing that might have still gotten me to buy the book.

Happy to be of service. The stylistic variation is probably it’s main selling point and if that doesn’t float your boat… I’m the kind of person who would probably get the next Clowes book sight unseen despite my experience with “Wilson”.

“Ken Parille does tend to favor close readings of narrative and technique as opposed to content on his blog.”

You’re correct. I wasn’t thinking about that.

” On the other hand, as noted above, the majority of critics out there seem to like it. If there was a metacritc score for comics, “Wilson” would probably get something like 60-70%. I would, however, like to read someone make a good case for its excellence as a story.”

I guess it depends where you go looking for reviews. From the day it came out–heck, the week before it officially came out–many of the hardcore comic sites were pretty much already killing it.

I noticed a big difference between the reviews of the “hardcore” comic fans, which were largely negative, and the “mainstream” media (newspapers, magazines, etc,.), which were mostly positive.

Really? Which hardcore sites are you talking about? I must have missed them in my initial trawl. Some of the people who did like “Wilson” might be said to be among the most prominent and knowledgeable alternative comics critics around: Sean T. Collins, Paul Gravett, Ken Parille, Tom Spurgeon, Tucker Stone.

Huh, that’s a big list of supporters.

Suat, there are the ones you listed them in your review: JOG, Jared Gardner and Douglas Wolk, although they are negative towards WILSON to varying degrees. And the Comics Journal message board thread you linked to is nearly 80% negative fan reaction. The Savage Critics roundtable discussion has also apparently invited more negative fan criticism than positive.

And although not very evident online, I have not come across one female comics fan who has really liked it, and I talked to a number of fans this weekend at TCAF in Toronto when Clowes was up here. Maybe that has warped my impression of the overall reaction to the book (which, as you say, has probably been mostly positive), but I’ve pretty much been hearing non-stop about how disappointing it has been for them. Of course, then I would open up a weekend review of WILSON in the Toronto Star and National Post and read about how great it is, but it jives dramatically from the first hand reactions I’ve received.

Here’s another positive review from a non-comics source….

Thanks for the clarification, llj. Interesting anecdotal evidence re: female fan reaction.

Don’t know what to make of that Splice Today review, Noah. I can’t tell if the writer was happy or unhappy with the book, which is unusual for a mainstream source. I would say more “meh” than “positive”. The fact that he calls “Like A Velvet Glove Cast in Iron” “peerless” suggests that we might have to take everything that follows with a pinch of salt.

Yeah; I probably shouldn’t have bohtered to link, but there it was…sorry about that!

Doesn’t Tom Spurgeon’s review make a case for the excellence of the story?

It’s too early for me to say for sure (I’ve only lived with the book for a week), but I think this is as strong as Ice Haven or David Boring. It’s more straightforward than those books, at least in terms of the plot and the storytelling choices, but I think Wilson is a more complicated character than anyone in those stories. As much as I like Ice Haven and David Boring, the characters feel like takes on literary types, whereas Wilson feels more fully drawn from life. I’d say that the strength of the story is in the strategic way it reveals this character to us. You get a picture of the gap between Wilson’s intellectualized idea of how we should live in the world and his (lack of) actual capacity to pull that off. Wilson’s ideology acts as a set of blinders: he thinks Big Thoughts, but he’s blind to the big picture of how people connect with one another and how the way we go about making and maintaining those connections have consequences. (That comes across in Clowes’ storytelling choices, too: the way Clowes leaves important details off page mirrors the way that Wilson tries ot shut out the stuff that doesn’t fit into his worldview.)

(Not that you mention it directly, but because it came up in some of the linked reviews: I’d add that I don’t think Wilson is much like Larry David’s stuff at all. David’s comedy is about the difficulty of navigating unwritten social rules in an era where the “old” traditions of civility are (a) constantly undermined and (b) being replaced by stuff like PC, self-help culture, etc.)

Jon, thanks for letting us know why the book worked for you. This part is especially useful and rarely mentioned:

“That comes across in Clowes’ storytelling choices, too: the way Clowes leaves important details off page mirrors the way that Wilson tries to shut out the stuff that doesn’t fit into his worldview.”

I haven’t read Ice Haven or David Boring since they were first released but, if memory serves, the main character in those books are less grounded in reality (as are both those stories as a whole).

As for Tom’s review, you may be right. At least, he explains why he likes the book and how it connects with him personally. This from his review:

“…Wilson’s desire to engage and find some place for himself became affecting in a way I never would have guessed reading ten of those early punchlines in a row. Clowes is careful not to let his character find unearned change, and our hero is letting loose with fanciful nonsense almost up to the final one-pager. But when Wilson says things like “Christ, it’s unbelievable how you go from feeling young to old in a few short years” it’s hard not to agree with him, and maybe even connect to something that’s also true of ourselves.”

That element of identification (implied or plainly stated) has cropped in a few of the reviews online. A bit more subjective than most opinions but at least I understand the tipping point in his assessment of Wilson. Readers who find the book interesting would better convey their feelings by elaborating very specifically on what they find so interesting in his character arc.

I’ve read it now and must say that I think you’re selling it a bit short, Suat. Initially, I also thought it might be one of his weakest books, but I’m not so sure now, having thought some more about it. The Wilson character is probably Clowes’ most complex so far and, as Tom notes, he shows a very mature willingness to engage with issues of growing old and death, whence comes the slight banality of certain passages, but also, ultimately, the story’s resonance.

I’m not sure, I think I shall read it again and let it percolate a little.

Ng, are you sure that Wilson’s daughter was taken against her will? That never occurred to me. The scene in the car seemed to imply that she wanted to leave her adopted parents. Obviously, it would have been kidnapping either way.

“adoptive parents”

Jack: I think it’s possible that she went along willingly at first before being prevented from leaving. Hence all the crying on page 44 (she seems miserable in that scene not happy). After that, maybe a bit of Stockholm syndrome. There are enough spaces in the narrative to allow for that. But I understand what you’re getting at. It’s possible that she went along willingly throughout. Both scenarios are possible even with the punchline on page 51, and his daughter and ex-wife pointing the finger at him when encountered by the Feds.

Matthias: Off hand, I would say that Enid from Ghost World is more interesting than Wilson (Noah would vomit if he read this). But I see what you, Jon and Tom are getting at – the idea of taking on a life from middle age to senescence and all the minute changes that entails. In a way, Wilson seems more “real” than a lot of Clowes’ recent characters, a lot of whom inhabit more imaginary landscapes. I may change my mind in years to come but at the moment, the developments and insights in Wilson seem banal, superficial and inauthentic thus creating barriers to my emotional connection with the work. For example, Tom talks about how “Clowes is careful not to let his character find unearned change”, but the abbreviated nature of the comic (its length and structure) works against this. There’s not enough space or detail in Wilson for the reader to feel this change.

“Noah would vomit if he read this”

Not at all. I don’t think Enid is the least interesting of all possible characters. David Boring is less interesting, as just one example.

Yeah, I guess either way is possible. I just thought she was crying because two creepy people popped up and claimed to be her real parents. Sorry I called you “Ng” by mistake.

No problem. It’s really my own fault for willfully putting my surname in front on an American site.

Ng, two things. First, you misread the scenes with his daughter. Of course she’s crying in misery. Seeing her real parents for the first time would be a traumatic event for any adopted child. But they didn’t forcefully kidnap her. That’s so far out of whack with Wilson’s character that I frankly find myself questioning the rest of your review. Second, “a period of 6 years”? Come on, man. If you’re gonna be a writer you can’t put blunders like that in print.

Not trying to be a jerk, but there’s such a dearth of smart reviewing in comics.

Terry, you’re welcome to be as much of a jerk as you like and you should definitely question critically any review which pretends to analyze a work of art.

However, as to your first point, I’d say your closure of possibilities does a disservice to “Wilson” as a whole. The spaces in the narrative are an invitation by the author to interpret; for the reader to insert himself into the narrative and decide for himself. At a very basic level, Clowes’ comic questions how much we can know about any person in real life. The delayed revelation and ambiguity which the Sunday strip format allows is a large part of the comic’s attraction.

In the scene in question (“Panda Express”), we are clearly meant to assume that Wilson and Pippi gently confront their daughter (Claire) with her true parentage at which time they retire to a cafe to have a drink. Claire doesn’t say a word throughout and is seen crying over the course of the six panels. What follows is a natural segue to the scene in the park where she is seen to be quite calm but still totally silent.

What Clowes doesn’t tell us is how Wilson confronts his daughter. Does he have proof? Does he bully her into believing? Does he trick her into the cafe before impressing the truth on her by means of his glowing personality? Or is she merely a gullible young child? The choice is the reader’s to make.

As to your second point, I presume you’re not suggesting that the period of time Wilson spends in prison isn’t 6 years since the chapter titled “Good Behavior” has the following lines by Wilson: “I’ve been out of the loop for six years…” and “Six years of hard time with the lowest scum imaginable!” Or maybe it just doesn’t sound like good English to you? I’ll admit it’s not poetic in the least but it seems quite understandable from my perspective.

is it okay that i used some of the pictures here in my review? (http://iamasadcunt.blogspot.com/2011/03/review-wilson-by-daniel-clowes.html)

i enjoyed this review by the way

Derek, we don’t own the pictures. They’re copyright Clowes, usable in reviews by fair use.

Wilson was pretty godawful— but since it only takes about an hour to read…and it was free from the library… I can’t complain too heavily (what follows is complaint). To me, it reads largely as a pastiche of Ivan Brunetti…and that’s not exactly a compliment. The varying artistic styles invite close examination and interpretation, but I don’t think it really rewards deep thought. It’s hard to get past the all-but-non-existent story, the sad lack of character development, etc. I’m sure if I re-read it ad infinitum, I might find some depth there, but it definitely doesn’t invite me to do so. Wilson is such a jerk in so many situations that the glimpses of his “humanity” that we get hardly seem to balance the ledger in any way…. And the crime and punishment Wilson commits and undergoes just struck me as so out of character and so willfully incongruent (and to little purpose) that it was hard to care even a little. The “gag strip” structure seems to be a foolish choice if there is little to no humor…as the subversion of said structure only strikes a reader for a page or two—Then it just becomes monotonous. Life just isn’t this humorless and miserable—Other than that, it was a wonderful read.

Even the supposed moments of “depth psychology,” linked to water images just strike me as a complete cliche. I mean, Freud associated water imagery with the mother (the idea of the “Oceanic”)–so Wilson links his need to see his mother with his need to see the ocean? Just seems like a transparent transcription of somebody else’s ideas, with little or no creativity involved. Maybe Clowes isn’t into Freud and has no idea about these ideas…but I’m not sure if that makes matters better or worse. It just seems SO obvious and heavyhanded that it may be a parody–but it’s not funny enough to actually work as a parody either.

Clowes knows his Freud.

I don’t think the thing with the water was about his mother. I think you should read my review I linked, I don’t think you would like it at all but I would be interested in your response. Also are you the actual DJ from “Eric B and Rakim”? Mad props if you are.

I would definitely like it less if Clowes meant for us to bring Freudian interpretation (womb-birth-mother) into the game. So in this instance, I’m “against interpretation” if only to give the author the benefit of the doubt.

Isn’t his wife a psychoanalyst? Anyway, Wilson only gets lamer with distance.

Much as I love “Paid in Full”–I can’t lay claim to that identity. I have an Eric B and Rakim trading card that a student gave me though…