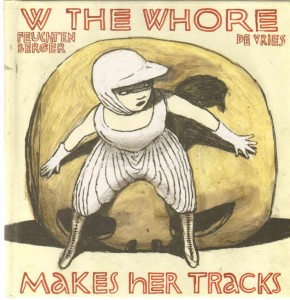

Over in the comments to Erica’s introductory post, Robert Stanley Martin commented that the art of Amanda Vahamaki’s The Bun Field (the subject of the last Fish without Bicycles) doesn’t appeal to him. I’ve heard similar things recently from male friends about both Vahamaki and Anke Feuchtenberger, specifically W the Whore Makes Her Tracks. Although Feuchtenberger’s drawings are sharper than Vahamaki’s with much more contrast, they’re aesthetically related (maybe someone with more art knowledge can give me some vocabulary here), and there’s indeed something about this aesthetic that doesn’t appeal to a number of men I know. Not all the men of my acquaintance – the book was recommended to me by a man. But women seem to like it more. It’s not a scientific sample, but it’s good enough to trigger a blog post.

In the same comment, Robert also called out an objection to French Feminism, specifically Hélène Cixous, who is perhaps best known for coining the term écriture féminine – used by all the French Feminists to describe a kind of richly metaphorical, non-linear writing that “inscribes the female body,” playing off the Pythagorean table of opposites and trying to embody the elements associated conventionally in the West with the female half of the table.

| Male | Female |

| Odd | Even |

| One | Many |

| Right | Left |

| Straight | Crooked |

| Activity | Passivity |

| Solid | Fluid |

| Light | Darkness |

| Square | Oblong |

In prose, this project often results in writing that is nearly impossible to parse; the (intentionally) less-than-comprehensible Marine Lover of Friedrich Nietzsche by Luce Irigaray (whom Robert also has issues with) is the definitive case in point.

Feuchtenberger’s work, in contrast, strikes me as far more successfully accomplishing Cixous’ ambitions for “women’s writing”:

“A world of searching, the elaboration of a knowledge on the basis of a systematic experimentation with the bodily functions, a passionate and precise interrogation of her erotogeneity.”

Her work “inscribes the body” with a crystalline clarity that the prose experiments never quite master.

Given that, and the apparent frequency with which men dislike this style of art, does the reaction against the aesthetic imply that it alone constitutes something like an “écriture féminine” for comics, something that is inherently, if unconsciously, challenging to male readers and empowering for women? It’s not impossible, especially if you’re very Freudian, but I don’t think so: The shadowy, filtered aesthetic gives a surreal quality that makes room for Cixous’ metaphorical, non-linear écriture féminine, but the aesthetic in itself isn’t sufficient to make that happen. Although it’s common to see this type of aesthetic deployed in the service of metaphorical or non-linear graphic narratives — narratives which are always, somewhat condescendingly, called “dreamlike” — the aesthetic doesn’t mandate any particular content, and I’m hesitant to gender a visual style independent of what it represents.

I find Feuchtenberger’s book remarkably more “feminine” than Vahamaki’s, but the gendered perspective is not in the aesthetic so much as in the imagery. I would not describe The Bun Field in Cixous’ terms, whereas they seem precisely appropriate for W the Whore Makes Her Tracks, despite the surface similarities in aesthetics (and with no implication of intent). Whereas Vahamaki’s text deals with the experience and perception of older children of both genders (a topic often interesting to women but not exclusively so), the subject matter of W the Whore Makes Her Tracks is explicitly sexed: the perspective not (only) of a woman’s mind but of the female’s body.

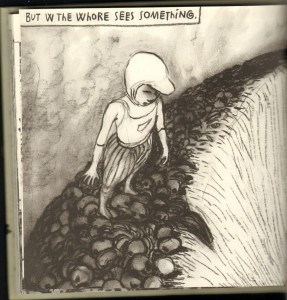

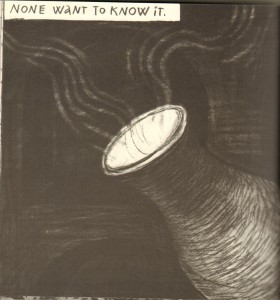

There is something very much interior about this style of art, something dark and fluid and in keeping with the right side of Pythagoras’s table. It certainly makes sense aesthetically for Feuchtenberger’s narrative. The perspective is intimate – no wide angle here – and the light is dim. The landscape is clearly imagined rather than seen; it does not yield readily to the creation of a “mental map”, except metaphorically. It is immensely difficult to orient yourself in space and impossible to orient yourself in time, except very slightly in terms of relative time internally to the narrative (such as it is.) The use of one panel per page rather than a grid enhances this sense that the story’s movement through time is less important than the visual metaphor of the landscape. The narrative is almost entirely metaphorical, and the overall effect is, again, either of the surrealist mindscape or the imagined Other-world.

But these elements are only obliquely “feminine,” and insufficient to account for any immediate aesthetic reaction against this kind of drawing. It seems wrong to say that men have an unconscious reaction against metaphorical, dreamy, non-linear stories. (One of the men who objected said, “It’s not that I don’t like it really. It’s that it looks like it’s going to be a lot of work.”)

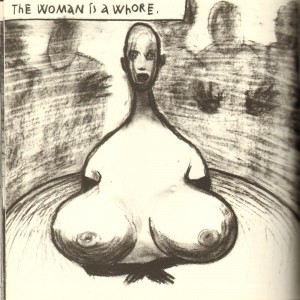

Although the aesthetic itself is not gendered, it would surely be difficult for a man — at least a heteronormatively gendered man — to “recognize” the imagery in the book as true to his experience, especially the more metaphorical imagery:

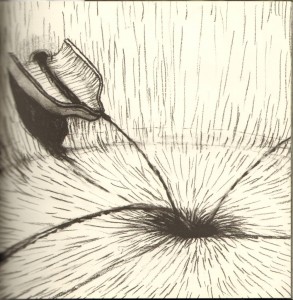

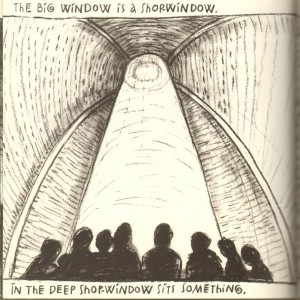

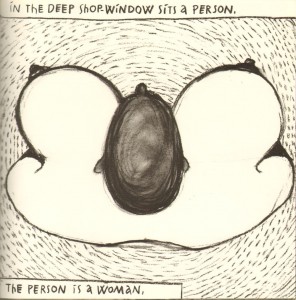

Feuchtenberger creates the contours of her landscape out of fragments of the female body during the sex act – but unlike most representations, the perspective imagines sex from the interior of the woman’s body:

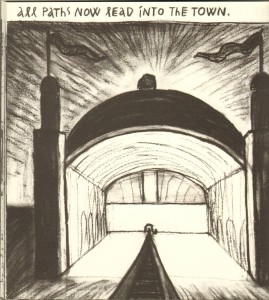

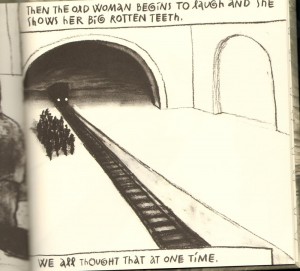

Of course, men can certainly “parse” the imagery – all the typical Freudian visual metaphors for sex make appearances in the book: tunnels and trains, phallic-shaped anythings, orchid-like flowers…they’re all there, and they still mean the same thing.

These images are semiotically packed: as stand-alone panels their signification is already varied. The last image for example is simultaneously (most representationally) the view of a woman from above, a view of sex from inside the woman, and a view of birth from outside. It also carries narrative significance for the book’s foregrounded conceit about sexual objectification and the marked-ness of the female gender.

But that turned-around perspective resonates more with a woman’s experience of her body…

…than with a woman’s visual image of her body, whether from the mirror, photographs, or a sexual gaze.

So what can we conclude from this? Despite this sexual subject matter, the book is not erotic. Bart Beaty comments, in a discussion of Feuchtenberg’s earlier “W the Whore” in TCJ 233, that “even in her nakedness none of the images are particularly sexualized.” Although I don’t have the earlier book to compare, the statement is true for this book as well, even though W the Whore (the character) is not naked very much in this volume.

But why is it that these evocative sexual images don’t have an erotic effect?Of course, they’re not intended to have an erotic effect, because that would undermine the critique of objectification. But what is it about them that interferes? Beaty’s observation puts into perspective not only how much our ideas about what counts as “erotic” are shaped by artistic (aesthetic/dramatic) representations of sex, but how conditioned we are to perceive even our own sexuality from the external perspective of most of those representations: “sexualized imagery” generally is based on something you can see during sex, not on things that you feel. Watching sex on TV or seeing sexually provocative images in a comic or illustrated book doesn’t replicate the experience of sex, it replicates the experience of voyeurism. This is – or at least has the potential to be – an immensely objectifying construct for both men and women, making sex less of an experience and more of a performance. To no small extent, the immense anxiety over body image that many women suffer is connected to this distorted, externalized perspective — as Feuchtenberger’s narrative explicitly points out.

Beaty describes Feuchtenberg as “exploring the outer margins of the comics form with seemingly no interest in making concessions” and “casting the very project of comics storytelling into doubt,” but I think this is too narrow a vantage point to accurately discern what makes this work so distinct an artistic achievement. The conventions of comics storytelling are no more called into question than the conventions of films and books for how to represent stories of women’s erotic experience. Comics form is part of the same broader culture of representation, and it is illuminating to shift the emphasis away from limited questions of form to questions about the extent to which gendered – in this case, sexed – erotic experience informs and shapes perception in general.

It’s a bit of a truism that women find erotic fiction much more arousing than erotic images, and Feuchtenberger’s perspective throws some light on why this is: representing the “inside out” experience of feminine sexuality is, on the surface, much more difficult in art than it is in words. Prose is appealing – and representational art vastly limited – for capturing interior experience: mind, imagination, sensation. In prose, you can just describe the experience, whereas the visual artist has to find a way to bring non-visual sensation to mind through visual means. Resonating with Cixous’ challenge to women writers, Feuchtenberger’s images make clear that French Feminism is profoundly physical but not in the least bit scopophilic. (The French Feminist emphasis on physicality has resulted in charges of essentialism by a great many Anglo-American feminists, including Susan Gubar, whom Robert also didn’t much like). When Feuchtenberger does represent scopophilia it is very distorting:

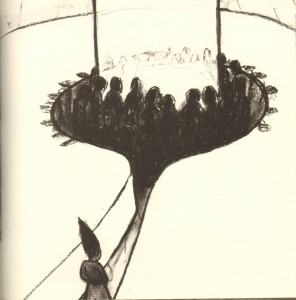

or creepy, represented by a crowd of anonymous watchers (also visible in images 5 and 6 below). The watchers represent that “experience of voyeurism” discussed above, and stand symbolically in the narrative’s interior space for the ways women internalize the perspective of these collective, objectifying voyeurs.

To parse the literal strain of the narrative, recognizing the distorting effects of this scopophilia is “freeing” for W the Whore, but ultimately futile.

Despite this rather despairing narrative thread emphasizing the futility of écriture féminine, Feuchtenberger’s text in conversation with Cixous’ is “freeing”: it allows us to see the effects of a cluster of binaries between text and image, voyeur and participant, inside and outside, seeing and feeling, male and female. W the Whore Makes Her Tracks illuminates the cultural insistence that “the body” is what we see from the outside rather than what we imagine and experience from the inside, and it turns that insistence “inside out.”

The conventions of illustration and representational art insist that we think of Feuchtenberger’s vantage point as “metaphorical” and “dreamlike.” And yet, Feuchtenberger’s most significant achievement in the book is very direct: the reminder that there is no reason why what we find erotic should be based on the perspective of the voyeur, and that there is so much more to the body than what that voyeur can see. Although I think it definitely matters that this book was written by a woman, it seems like that insight applies equally well for men.

You made me look up scopophilia, damn it.

I just called Lili Carre’s The Lagoon dreamlike, which certainly wasn’t meant to be condescending. It seems like thinking of interiority as dream makes a fair bit of sense…and I wonder if doing that is necessarily dismissing it. Freud (who’s a big deal for French feminist theory) thought dreams were more important than waking — or truer in some sense.

I also think it’s kind of funny to say that the French feminists are “accused” of essentialism. They’re essentialist, aren’t they? Again, it’s not clear to me that that’s a bad thing always (the opposite is relativism, more or less, which obviously can be its own insult.)

I guess in light of this I wonder about exactly what you’re after in this series. Saying that it matters that this book was written by a woman seems to come down, more or less, to the fact that it fairly clearly is interested in and addresses women’s issues. Which is reasonable enough — but you also seem to be dancing back and forth around the idea of there being some formal component of women’s art which makes that art specifically feminine (in this case, interiority and the refusal of the voyeuristic gaze.)

The thing about that is…what do you do with, for example, the most clearly female-created/centered/focused art/literature/whatever, which certainly aren’t especially interior, dreamlike, or non-scopophilac. I’m thinking of romance novels, women’s magazines and yaoi, to name just three genres that come to mind more or less instantly. Or the women interested in those things victims of false consciousness? Are they using male modes of art making rather than female ones?

I guess the point is the interiority you’re talking about seems like as much an aesthetic tradition as a particularly female one; it’s surrealism, more or less. And it just seems like it’s visual stance is as much about that high art tradition as it is about something that’s particularly distinct to women’s view of the world.

Which isn’t to say she doesn’t have smart things to say about gender, and it makes sense to point out that those things are tied to her experience as a woman. But…there’s a certain amount of evidence that women like voyeurism too, and that the way they try to turn the tables in women’s genre literature is not by flipping inside out, but by pushing guys aside and becoming voyeurs themselves.

What an excellent piece of writing about Feuchtenberger…sometimes I think of her as ‘the only cartoonist that matters.’ Thanks for this.

Thank you, Austin! I’m immensely glad you liked it. We completely agree on her significance: I could have written four times as much as I did and still not exhausted everything there is to say about this book. It’s absolutely extraordinary.

I’m putting this squarely at the top of my list for the best comic I’ve ever read, leaps and bounds over anything else. And I’m considering putting it at the top of my list of best fiction I’ve ever read, period.

Noah, I think my objection is more to the overuse of “dreamlike.” It’s not that nothing is ever legitimately dreamlike; it’s that so many times you see the term used to mean “too metaphorical to figure out what it means on a light reading.” I haven’t read your Lille Carre piece yet (I will! It’s been that kind of week…) but I’m entirely confident you didn’t do that. My objection is to when the term is used as a way of avoiding the effort to grapple with the semiotics of things whose meaning is not on the surface. That’s what I find condescending: “oh, you couldn’t possibly be saying something that I just don’t get; you’re just being dreamy.”

But I think even in Freud it has to do with unconscious experience, and — although the French feminists absolutely deal with the unconscious — I don’t think this book is about the unconscious. It’s too concerned with physicality, perception and conscious self-image. In this case I think conceptualizing it as a dreamscape is missing the most incisive — and feminist — intervention it makes into the gendering of Western culture.

I think I agree with what you’re saying about interiority and the aesthetic tradition: that’s the contrast I was trying to get at (and maybe failing?) in the distinction between the aesthetics and the imagery. I agree you can’t pin the gender on the look and feel. But I think that you can pin it on the imagery.

The French Feminists are pretty hard-core Lacanian and I feel confident they would call female-oriented genre fiction “phantasy.” Phantasy’s not exactly false consciousness – it’s a truth of the Symbolic. But it’s not as basic, I guess, as fundamental fantasty and I don’t think they’d call genre fiction fundamental. It’s too socially determined and fundamental fantasies mark the moment of inauguration into the Symbolic, before the culture’s had a lot of time to act on the psyche.

That’s also what’s behind my saying they’re “accused of essentialism”: the critique generally comes from social constructivist feminists who just want them to pay more attention to the Symbolic and the ways in which biological sex doesn’t match up with psychological gender, or just the ways psychological gender plays with culture. Yet, they’re just more concerned with what attention to the biology of women — as lived experience and as a metaphor — can offer to art and to our understanding of feminine psychology in normatively gendered women.

I wouldn’t call that essentialist: it’s just interested in a different aspect of gender from the one that Anglo-American feminists privilege. It certainly seems to me that it’s meant as a criticism and a willful misunderstanding of their project, but if you want to queer the word “essentialist” to be a good thing, I’m totally ok with that too…

I also think they would say that Surrealist interiority is gendered male — at least, I’d say, that you shouldn’t assume that all representations of interiority that are similar aesthetically are similar semiotically. But maybe we disagree on this: I don’t find the interiority here to be all that similar to the Surrealists’, actually: it’s, again, much too conscious. It’s not abstract interiority — as in the psyche/life of the mind. It’s concrete materiality from the perspective of inside the body.

Well, concrete materiality from the perspective of inside the body…made into a metaphor for the abstract interiority.

What I was trying to say is that the imagery is more concrete than that of the surrealists, which is legitimately “about” the psyche and dreams…there’s an extra step here. A BRILLIANT extra step…

Very interesting piece, Caro! Feminine, masculine or both, I know I love Feuchtenberger’s work more than just about anything being produced in comics today.

I think, perhaps, that your use of Cixous’ binaries limits the interpretation of Feuchtenberger’s images — yes, they deal with interior life, but rather than attempting precisely to describe particular emotional states, as one might in prose, it does what this kind of art has always done — it creates a suggestive field of emotional resonance, encouraging you to go your own way.

As for the comparison with Vahamäki, I actually think the younger artist briefly studied with Feuchtenberger, although I can’t seem to verify that at the moment (anyone?). In any case, her style and approach, like those of so many of her contemporaries, is heavily indebted to Feuchtenberger.

Well, I’ve read neither as much Lacan as you, nor as much of the French feminists your talking about, nor any Feuchtenberger…so I think I’d probably better bow out here….

It should definitely be taken as a limited interpretation, Matthias: it’s just one strand of meaning that’s going on in a book that’s got dozens of strands of meaning.

But I want to emphasize the same thing to you that I did to Noah: in my interpretation, the images are not dealing with “interior” life or emotional states. They are just as “visual” and just as physical as any traditional artistic representation of sex.

This book doesn’t just represent the emotions associated with sexual objectification or the psychic constructs of identity that result from it: it does, literally, represent the sex act as if someone were watching it happen from inside a woman’s body. The difference is that she posits a physical “interior” eye and represent the familiar physical act from that perspective. That eye has to do with the imaginary body: the one you feel yourself inhabiting but can’t actually ever see for yourself except in a mirror or a photograph, and she builds a gorgeous metaphor on that.

Those are not representations of emotions or interior life: they’re representations of physical sex. They’re metaphorized, yes. But they are also literal (or whatever the art word for “not metaphorical” is.)

That’s why I think it matches up so well with Cixous, with her emphasis on the way a woman’s “erotogeneity” completely disrupts the normative field of subjectivity (in representation, at least).

Although I think there’s definitely a “suggestive field of emotional resonance,” that phrase doesn’t capture anywhere close to how really bleepin’ brilliant this book is, because it misses the extent to which this is also a representation of exterior life and physical experience.

Lots of artists, Vahamaki included, pull off emotional resonance. But getting the ecriture feminine right, actually inscribing the feminine body without falling prey to the scopic drive, is, as far as I know, absolutely and completely unique to Feuchtenberger. It remains experimental in prose after decades of experiments; it is fully realized here. I’m not kidding when I say she has succeeded where everybody else has failed!

I swapped a sentence there if anybody was reading that last comment: cut and paste error.

Noah, you hold your own just fine on this stuff.

I’d like to do an expanded version of this once I get a copy of the first book, and your comment is very helpful for sorting out what pieces of the explication are lacking…the word “interiority” is clearly confusing matters, and both you and Matthias (I think) missed, or at least undervalued, how important it is to this article that the sex imagery be literal/physical as well as metaphorical.

Well, all right, if you’re going to encourage me…

It seems weird to talk about any artistic representation as “literal”. I guess what you’re saying is that it’s an effort to represent sex in a particular way, which may be stylized (since all representation is stylized) but isn’t symbolic. That is, it’s inside the body rather than inside the mind.

Which does get at some of the problems American feminists have with French feminists, I guess; the idea that women are more associated with the body, or more in their body, seems to cede the mind to men in a way that doesn’t seem ideal, at least from some feminist perspectives.

It comes down to a basic strategic divide; is the thing to do with a hierarchy to opt out (which tend to mean in practice staying on the bottom) or to insist on being allowed access to the top (which results in “new boss same as the old boss.”) Though it’s also possible to hope to export a different way of seeing — which is reasonable enough, especially when you’re talking about art rather than political action per se.

“Phantasy’s not exactly false consciousness – it’s a truth of the Symbolic. But it’s not as basic, I guess, as fundamental fantasty and I don’t think they’d call genre fiction fundamental. It’s too socially determined and fundamental fantasies mark the moment of inauguration into the Symbolic, before the culture’s had a lot of time to act on the psyche.”

I’m pretty skeptical that what is happening in Feuchtenberger is less socially determined than female genre fiction. Girls are into romance really early on; the appeal of something like yaoi across national boundaries suggests there’s something there that resonates fairly widely. And the arguments about women=body, or even “women prefer verbal over visual” — those don’t seem less socially determined than any other male/female binary (which is to say, it’s impossible to figure out how socially determined they are beyond a very general “at least somewhat.”)

Just because it’s socially determined doesn’t mean it’s not worthwhile, of course.

I agree the word “literal” is weird. I guess I’m trying to point out that it’s representational? This only really works if you start by seeing it as representation in exactly the same way that a porn film in representation: here are images of genitals engaged in sex.

Then one thing is changed: instead of the “gaze” starting from the eye of the voyeur, it starts from this posited “interior” eye, so that the fully representational depiction of the physical act of sex immediately becomes a metaphor, because that interior “eye” is the “mind’s eye”. What’s at stake in the representation is body awareness rather than body appearance: the mind being aware of the body. There’s a baseline physicality to that, but the baseline is very quickly “distorted by scopophilia.”

The baseline, though, is inescapably sexed for most people. So theorizing that baseline is “theory at the point of difference.” Although I wouldn’t say Feuchtenberger’s work is not socially determined, I would say that Feuchtenberger has chosen as her subject the “point of difference” before the culture begins to act.

Perhaps where I part company with the French Feminists is that I think that “ecriture masculine” really doesn’t exist yet either: I agree it’s reductive to map binaries like abstract/concrete and mind/body onto male/female, and when they argue that the writing we’re used to is masculine that’s essentially what they’re doing.

But there aren’t a lot of satisfying ways of representing body awareness by either gender without just depicting what the body looks like to someone else and what the world looks like to the person inside the body. It’s hard to depict in any representational form what the mental sense of one’s own body is and how that affects one’s identity — but who doesn’t accept that body image is a huge part of identity, for men and women?

I think it’s very important for feminism to theorize body image in a way that pays less attention to “what other people see when they look at you.”

There’s a sense in which the French Feminists allow us to re-imagine gender power dynamics by reminding us of the “essential” baseline for gender, the materiality before all the social and cultural baggage gets layered on, so that we become more aware of how that social and cultural baggage actually gets layered on. I was actually a little surprised when Robert lumped them in as “man-hating feminists” because I’ve always felt they advocated deconstructing the power dynamics from the ground (the inescapable difference) up, without advancing any idea that one or the other gender has to be “on top” at any particular time — or the idea that there’s any necessary or uncomplicated map between body awareness and gender identity.

It’s definitely a gender theory that starts from an absolute difference, but I don’t think the concept of ecriture feminine only allows for the feminine. I think you could try to write the masculine body in the same way: male body awareness is, in fact, no more scopic than female body awareness, and this problem that you can’t actually see your own body is true for both genders. Those are the elements of ecriture feminine that interest me the most, rather than the more overtly policial ones: the idea that books like Marine Lover are somehow going to solve problems like sex trafficking or honor killing is ridiculous…

I wonder in some ways how different what you have Feuchtenberger doing is from what porn does actually is, though. Linda Williams makes a quite convincing case that pornography is obsessed with discovering, or uncovering, something essential about women — something which I think could be described as the interior experience of women’s bodies. In that sense, the question being asked — what is the experience of women’s bodies form the inside (with the obvious double entendre) maybe hasn’t changed so much.

Williams points out too that the desire to discover interiority is often more important than, or precludes, eroticism — which also maps onto your points about Feuchtenberger’s interior experience of the body not mapping as erotic.

Commercial interlude: A lot of people in the U.S. picked up Feuchtenberger’s books when they were brought over and listed in Diamond by Bries over 10 years back. Sometimes with English translations or translation inserts. She appeared at an SPX/ICAF conference with Martin Tom Dieck around that time as well. Have no idea who handles these books (in translation) nowadays.

Of no importance to people like Matthias but useful for people who can only handle English. She appears in one of the Actus anthologies in English as well. “Das Haus” was quite a lovely book if I remember correctly but that one isn’t available in English.

Feuchtenberger art on sale at Adam Baumgold.

Wow, I had no idea this was so hard to find. Caro, where’d you get this? And in English no less?

And there’s this article on Feuchtenberger with links at Domingos’ website as well.

I bought it from Austin! (Sparkplug table @ SPX)

I take it Suat’s comment means I’m going to have the devil of a time finding the first volume, eh?

Not really. The first volume appears to be published by Bries so it should be easy to order from Ria Schulpen who runs the place. She used to carry a lot Feuchtenberger’s German albums as well but I don’t see them on her website. A really good comics shop might carry her stuff as well. Maybe Austin knows more.

She’s not a one note artist so you’ll probably find a lot of the back catalog quite worthwhile.

Noah:

I think if you take my argument in isolation you can make a case that it’s similar to what Williams identifies (my dissertation director studied with her, btw, so there’s a direct lineage for you).

But Matthias rightly pointed out that this stuff is only a fragment of what’s going on in the book; you get so many many more levels and strands operating in Feuchtenberger than you do in most things we stick with the label “porn,” and that makes a huge difference in the meaning you end up with in the end.

That said, I don’t think the desire to “discover something essential” that’s at work in porn is at work here, because the difference between experiencing the body of the Other and experiencing the body of the self is a pretty significant difference: one is colonizing and the other native. But that raises the interesting question of what male readers are supposed to get out of this encounter with the “inscribed female body.”

I mean, I don’t need female body awareness explained to me or illustrated for me in order to understand it: I have loads of personal experience. For me it’s immensely joyful to see it represented at all, and just breathtaking that it’s done so beautifully. It doesn’t satisfy a curiosity; it’s just…well, it’s like reading in your native language after spending years in a foreign country.

I generally have a very hard time identifying with things that “women” say are “women’s experience” — the things that “women’s genres” are supposed to appeal to — because they never map to my experience. But this felt very incontrovertably female to me. It didn’t feel less socially constructed than genre fiction, but it did feel less culturally constrained.

Maybe I’d just rather be validated than empowered and most women’s fiction that isn’t completely normative feels like empowerment fantasy. And empowerment narratives always ring very false to me, very “phantastic” — whether they are intended for men or women.

(Or maybe it’s just “high art” enough that it’s in a position of power over those constraints.)

My guess — maybe Matthias knows this for real? — Feuchtenberger strikes me as having started from Surrealism (like Williams) but rather than critiquing the limitations of the vantage point through irony or something, like you so often get from feminist work, she just “turned it inside out.” It’s just astonishingly sophisticated and really satisfying. Austin got it just right: she matters.

But back to your point as I have wandered off into panegyric again: I guess I’d say that this understanding of ecriture feminine is a different mechanism from porn, but absolutely the same turf as what Williams calls “body genre.” Feuchtenberger twists the phenomenon Williams identifies around in a really unique way, but it’s the same general turf. I’m completely comfortable with the idea that this essay belongs in the same basket as Williams’ work…I’ll gladly claim her as my intellectual grandmother!

Suat: I’m going to buy the entire back catalog even if I have to buy the German editions and make my German-speaking friends translate. (Scrolling through mental rolodex…)

Dylan Williams of Sparkplug bought a bunch of copies of her work from Bries and was distributing those copies until they ran out.

I bought some of those copies from him when I was working at Forbidden Planet…for a while, FP had a pretty complete run of her work.

Still, for an artist of her strength, i think its crazy that in this so-called golden age of comics reprints and translations, her work is still hard to find for most American audiences.

Caroline: ‘der palast’ is one of her stronger works if you can track it down.

Thanks for clarifying, Caro — I think your interpretation is a compelling one and agree wholly that Anke’s art has a strong physicality to it, but to me it works as kind of an embodied awareness, rather than the more representational or scopophiliac impulse I first thought you were describing.

Having grown up in East Berlin, Anke started out not so much with surrealism, but rather feminist poster art, in the period just after the Fall of the Wall. She also did stage design for theater. But she clearly works in the tradition of surrealism as well.

There are three books in the “Hure H” cycle, the most recent of which is “Die Hure H wirft den Handschuh”, which is perhaps the most unheimliche of the lot! (And not yet translated into English). Please note that they are made in collaboration with the feminist writer Katrin de Vries and somewhat more literally articulates these themes of female sexuality than does Anke’s other work.

You can buy several of Anke’s books fairly easily through Amazon.de, or directly from her publisher Reprodukt.

“Das Haus” is also amazing — vertical comic strips as word/picture poetry, originally printed in Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung — and “Wenn mein Hund stirbt, mach ich mir eine Jacke”, which consists of a suite of related illustrations (no text), is just beautiful. “Somnambule”, a collection of shorter, and again, strangely related, strips (mostly without text), is an early masterpiece. “Die kleine Dame” is also great.

Great piece, Caro! I’m thinking that the reason some men don’t like this is precisely because it is visually sexual, without being meant as eroticism. Like Georgia O’Keefe’s flowers, which always seemed to make the men in the room a little pale. When overtly sexual imagery is taken out of the context of sexual stimulation, some people respond by calling it “ART” and some find it easier to dismiss it, since it no longer fits a neat box with a tidy label in their head.

Cheers,

Erica

I sent a link to Ms. Feuchtenberger and she was kind enough to reply. Presented with some editing:

“Thank you very much for that link. It made me very happy to read this, because it is rare, that someone is so occupied with my work…as far as I know. Thank you. The third book of W the Whore is now in translation by Mark Nevins, but I haven`t heard anything from Ria Schulpen from Bries for years….so there will be no English version of the last book. One thing, what came into my mind, when I read the article, was: my original drawings are mostly bought by men, my publishers are men and my gallerists are men. This means a lot for me, because all they help my work a lot to be known….and they like it! What do you think? (because, as I understand, Caro said , that mostly men seem not to like the drawings….)”

Her comments notwithstanding, the fact that there is no publisher waiting in the wings for an English version of part 3 of W the Whore only slightly lessens its chances of appearing at some point in time. Mark Nevins is a long time comics enthusiast who has had a hand in translating a number of European comics.

We might hear something from Caro once she returns from her holiday.

One more thing, Anke would like to make clear that “Katrin de Vries is the author. She invented the name W THE WHORE and wrote different pieces of prose with the character that is the literary archetype for our three books (which we did together).”

Thank you so much, Suat: I’m just starting to dig back into this and will have more, but I wanted to comment that I did have some trouble with whether/how to reference Katrin de Vries’ contributions when I was writing this, and it’s tricky because there’s so much territory that’s between the drawings and the words. Who “authored” the concepts in the imagery?

I thought about just using “Feuchtenberger/de Vries” throughout, because I’m sure there was meaningful collaboration, but then I didn’t want to take credit away from Feuchtenberger that she deserved since I really was paying more attention to the drawings than the words. I’d be thrilled to revise for accuracy if you have any advice to offer here.

Do you know — have the de Vries prose pieces on the character been translated (or, I guess, even published)?

Thanks again: I can’t tell you how marvelous it is to come back and see these comments.

Just ordered a copy of this, looking forward to it. Thanks for bringing it to my attention, Caroline.

My pleasure, Derik! It’s such a phenomenal book. I really need to get the rest of her work and revisit this post…

everybody should get as many of Anke’s books books as possible. she’s an amazing artist/storyteller. (what matthias wivel said) but this article is SO depressing. come ON.

Well, it made Ms. Feuchtenberger happy according to the comments. So perhaps mileage varies?

Mileage definitely varies with regards to what anybody finds depressing. (For example, I would never say AF was an “amazing storyteller” because that would be damning with faint praise if I said it — anything that focuses on story really depresses me.) I’d expect this piece generally to be both too academic and too French-feminist for any reader not interested in that sort of thing, though.

One of the things that’s so wonderful about the book’s achievement, to me, is how readily it allows for both this type of intricate feminist reading as well as many others — keeping all sorts of readings fully in play without making them work against each other. The plenitude of pleasures is one of the things that makes it feel so richly feminist to me.

It has an extraordinary atmosphere, for example, and that is rewarding even when it’s read straight (although I don’t think “straight” was de Vries’ intent, at least.) I thought a bit about whether to revise this to mention de Vries more back at the time, and decided to just be more diligent going forward — it’s really impossible to tell which bits come from de Vries and which from AF, but I’m not sure it matters — the art and “narrative” are so seamlessly integrated.

It’s brilliant work that should be getting much more attention than it gets from critics and readers, no doubt.

“anything that focuses on story really depresses me”

Good lord…anything?! Any narrative depresses you?

Do you have a reason? I mean, is there some sort of rationale as to why narrative is inherently depressing? Or is it just a more amorphous personal preference?

Lack of ambition?

I actually meant any piece of criticism that focuses on story depresses me. Art that focuses on story just kind of bores me, and yeah, if I spend too much time with art that’s primarily narrative I do get really depressed. It takes a little time for boredom to turn to depression, but it will. But no, not INHERENTLY depressing, by any means.

Remember that quote I put up from Francoise Mouly a few threads back (maybe forward from this thread) that Matthias said, lol, depressed him? I’m drawn to that again here. She was talking about “human” stories and said that:

That’s how I feel about most narratives, in fiction, film, comics, period — “oh, this is like that one; I’ve been here before”. Eddie Campbell has a blog post somewhere where he compliments some book by saying that it told him something he didn’t already know, which doesn’t happen very often. Somewhere along the line Pound’s “make it new” got turned into “keep it real,” to the great detriment of Art.

Contemporary artists tend to traffic in the kinds of insights that are very insightful and interesting when you’re in your teens and haven’t read a lot of books or in your 20s and haven’t seen a lot of life and much less insightful and interesting when you’ve read 20,000 books and lived for several decades. It gets back, I suppose, to that enrichment issue.

Comics artists are maybe much better at doing unexpected things visually. I gather that’s their priority, generally.

Mouly goes on to say that she’s more “drawn to things that are taking the basic components somewhere else and it’s true that is the attraction to books that deal with the structure of the work directly more than with the decoration of it,” and I agree with that too.

So it’s a non-amorphous personal preference, I guess?

So if Mouly believes that, why does she put such tediously predictable crap on the covers of the New Yorker?

Sorry; couldn’t resist.

Anyway, you’re point is not amorphous at all; makes perfect sense. There’s always a pull in art between keeping faith and innovating. I don’t really think it’s true that we’ve gotten much more obsessed with one end of that divide than the other — Pound and Hitchcock were contemporaries, weren’t they? And Hitchcock certainly was up for some conventional narratives in his day….

I think the appeal of narrative and pulp is definitely repetition and decoration; it’s variations on a theme rather than creating a new structure from scratch. But…I know you can appreciate that in some venues. Those Italian soundtracks you’re into (me too!) — they’re all rip offs and rejiggerings, ersatz elaborated copies of jazz and pop, not Schoenberg or Xenakis (maybe Morricone is an exception.) But that doesn’t mean they suck (I mean, some of them aren’t so good, but it depends.)

Not to try to argue you out of disliking narrative. Everybody loves narrative (including me); it’s nice to know someone’s immune. But I do think liking narrative is perfectly aesthetically valid (though, of course, lots of narratives are boring or uninteresting.)

Ha ha. I’m actually curious about whether she’d say the same thing now — that interview’s from 1982, so the points of reference have shifted. She may feel like the stuff we have now is perfect and that this sentiment is completely outdated — who knows? But it certainly resonates with me.

And I can appreciate the variations on a theme in comics — I very much enjoyed that Moore Swamp Thing. I find narrative most tedious in film, actually, because I can’t speed it up. (I can always read faster if I’m bored, but I lack the technology to watch the film in fast forward.)

But I think if you’re gonna call something “art comics” you need the more ambitious standard. As an artist, as a critic — and I think Feuchtenberger and de Vries in this comic aim for an extremely high standard. I recognize that I get a different, more meaningful, pleasure from unconventional art than I do from the repetition of genre and conventional narrative. Repetition is the fattening cholesterol-laden comfort food that makes me slovenly and slow if I eat a lot of it, so I’ve come to value the innovative, freshly prepared meals more…and Feuchtenberger really is one of the most nourishing.

It’s worth pointing out that we might be putting meaning into our commenter’s words since my emphasizing elements other than story might not be what depressed her. But it’s the only clue we have…

I was reminded, though, thinking about the Mouly interview, of this comment about literature appealing to adult audiences, and just the low threshhold of what many comics critics and readers and even cartoonists think comics are supposed to or even capable of achieving.

When I wrote this post I was very much inside the book (no pun intended), completely immersed in the pleasure of Feuchtenberger’s really masterful imagining (image-ing) of these themes of feminist embodiment, and I think in retrospect that I didn’t praise her directly enough for the sheer ambition of this book. I’ve said it elsewhere (in the conversation with Franklin Einspruch, but I can’t put my fingers on it) that Feuchtenberger in this book makes a contribution to the poststructuralist psychoanalytic feminist conversation by rendering the concepts in images: French feminism is so concerned with the material, tactile, visual, that the intrinsic abstraction of prose can be distorting to its purpose. I don’t think I made it clear in the post how essential the contribution of this book is to that conversation.

I agree with reneefrench that it’s amazing art, and I find it compelling storytelling — but there are lots of comics that have amazing art and compelling storytelling. But there are not a lot of comics that even contribute to, let alone transform, the landscape of a philosophical idea. Especially not of a philosophical idea that has nothing explicitly to do with comics. There are comics that push on and challenge the comics form (and I value those too, and this comic does that as well) — but comics that actually speak back to and challenge and add to contemporary thought? And to do that inside of such amazing art and compelling storytelling? An achievement of that scope and ambition is so very rare. This comic just radiates the potential that the comics form has to be the most transformative and essential medium of our historical moment. I sincerely hope nobody finds THAT depressing!

Do you think that Mouly has the freedom to put everything she likes on the cover of _The New Yorker_?

You’re asking Noah, right? I would guess she has lots of decision-making authority — and a great many factors to consider beyond her personal taste. But I know nothing of how the NY works…

I’d still be curious to know how her opinion has evolved, though. I think she is brilliant and fascinating!

Yeah; I have no idea what Mouly can or can’t do. I’d presume that she has some say since she’s nominally in charge. If you want to blame all the aesthetic lapses on her corporate overlords, that’s fine I suppose….

Not exactly a defense, Noah, but is there another periodical that regularly has better covers than the New Yorker? When I’m looking at the culture/politics section at newsstands and bookstores, it tends to stand out.

Sure. Try Vogue Italy. Or Zinc. I much prefer good fashion magazine covers in general to the winkingly smug “good design” crap that ends up on the New Yorker.

This, for example, kicks ass.

Artforum’s not bad either. I like this.

Blaming corporate overlords is great. It’s one of my favorite sports, but, in this case, there’s also the weight of tradition. A certain look that’s the magazine’s trademark.

Fun fact: Françoise Mouly worked for years at Marvel Comics as a colorist.

Face Front, True Believers!

sorry i wasn’t clear about why i found it depressing.

anke herself said, “One thing, what came into my mind, when I read the article, was: my original drawings are mostly bought by men, my publishers are men and my gallerists are men. This means a lot for me, because all they help my work a lot to be known….and they like it!”

i don’t know, i find statements like this depressing: “Although the aesthetic itself is not gendered, it would surely be difficult for a man — at least a heteronormatively gendered man — to “recognize” the imagery in the book as true to his experience, especially the more metaphorical imagery.

this suggestion that she’s making feminine art that men can’t “get” depresses me. it’s not true.

also, tunnels, trains and phallic shaped things are way fun to draw. sometimes a cigar…

That Artforum cover has more to do with Hirst than anybody at the magazine surely. Bjork as a flower, fair enough.

Somebody decided to put it on the cover. They get credit for that.

The text is actually great too, contrasted with the image. Works as a cartoon, I think.

Well, I definitely prefer the average New Yorker cover to that stuff.

You’re benighted!

Hm. Are you talking about the Artforum cover (in comment 45) Noah? I feel pretty sure there wasn’t much question that For the Love of God was the ONLY piece they could have put on the cover of that issue of Artforum. Didn’t that issue come out right in the heat of the debate about whether Hirst had really sold the damn thing or was faking it? I’ll have to check the timeline but it was right around the same time — it was surely the thing anybody would think of first when the issue said they were going to talk about “art and its markets.” I’d say it’s a pretty obvious choice — but probably a necessary one from a marketing standpoint.

I mean, it’s cool. But it’s not exactly DARING.

But fashion, yes — W magazine has had some great covers and even more interesting long-form interior spreads. I’m thinking of two particularly interesting ones — one with Julianne Moore from 2004 called “The Actress” that was photographed in part by Michael Gondry, and another with men in high heels (I think it’s one of the first covers Steven Klein did for them but I’m out of town and don’t have my copies handy so I can’t fill in the details). The Moore spread was 42 pages long in W’s large format — really unusual art choice.

But I kind of agree with Domingos that the New Yorker’s limited in a way that fashion mags aren’t. I also think Ms Mouly probably has the business of comics in mind as well, no? In the sense of giving cartoonists who might interest the NY audience as much publicity as possible, pushing the NY audience’s interest in cartoons toward an interest in comics, whatever the aesthetic?

Renee — I think maybe you’re misreading the statement you quote from me — although it’s obviously entirely my fault it’s not clear.

I wasn’t trying to say that “she’s making feminine art men can’t get;” that’s what I meant when I qualified that “the aesthetic is not gendered.”

What I meant by the statement you quote was something along the lines of as saying that men, when encountering representations of pregnancy, don’t have the same bodily memory through which to interpret the representation as women who’ve been pregnant: heteronormative men don’t (generally) experience sex as “being-penetrated”, and W the Whore is a book that turns the conventional images of sex-as-penetration on their heads, showing them from the vantage point of she-who-is-penetrated (being penetrated –> the penetrated being). But not just from the woman’s vantage point, from the vantage point inside her body, as experienced rather than seen, or, here, as seen by an inner eye/I.

To me, that’s an exceptionally powerful representation of (straight female) sexed sexual embodiment. I find it extraordinarily beautiful and compelling — almost entirely because it represents that sexed embodiment and does not erase the differences in sexed perspective or make everything about what is “seen”. Thinking of the imagery she puts to such meaningful metaphorical and political effect just as something “way fun to draw” would completely ruin the pleasure of the book for me (and, I think, would also erase the contributions of the feminist writer Katrin de Vries, which is an error I also made and am therefore very conscious of), so I’m very resistant to that. Although, certainly, if my reading ruins the pleasure of the book for you please absolutely set it aside and ignore it!

Anglo-American feminists have been getting worked up about and depressed over the French-feminist (psychoanalytic poststructuralist) understanding of sexed embodiment for decades — they think it’s essentialist because they’re materialist and this way of thinking about gender is so profoundly Lacanian — so it wouldn’t surprise me a bit if even with the clarification the interpretation is still depressing, if you’re coming from that different place. But I personally find the Lacanian branch of feminism so beautiful and celebratory and full of joy (jouissance!) that it was very meaningful to me to put this book in conversation with those writers.

I do think it’s interesting that I’ve had, entirely anecdotally, so many men of my acquaintance express resistance to this broad category of aesthetic (in the case of both Feuchtenberger and Vahamaki, specifically). I tried to make it clear by the various caveats and by pointing out that the book was recommended to me by a man, that my experience makes for an interesting data point, not the foundation of an interpretation. I’m also fascinated by the recent experience of someone saying that AF’s work is “not comics” but rather illustration.

In general I think the ways in which resistance to less-familiar aesthetics take shape is fascinating — but I also think that bringing it up here really derailed this piece, not just for you, and I do appreciate that feedback. I do plan to write more on this topic and I’ll do my best to avoid this confusion next time!

I don’t think I was claiming “daring”. Just better than the New Yorker. It’s a pretty low bar (at least from my perspective.) (And I didn’t know the piece! It’s pretty though.)

Being limited in a way fashion mags aren’t would explain why the New Yorker’s not as good, but wouldn’t really change the fact of the not as goodness. Same looking to promote the work of particular cartoonists. There are cartoonists she could put on there who would be great…but they wouldn’t be dry and smug enough, presumably.

But I’ve derailed everything, as is my wont. I hope you’re going to reply to Renee’s second comment…..

I did! (See comment 49.) (The Crying of Comment 49?)

I can’t defend the New Yorker’s art directory goodness against arty fashion magazines. Steven Klein versus Chris Ware just isn’t a fair fight.

But Francoise Mouly still rocks.

(Oh, and google the Hirst piece if you haven’t yet — the story is fascinating!)