I’ve decided to reprint an old review of The Times of Botchan to tie in with the recent release of the fourth volume in the series. The article was written about two years ago and was first published in truncated form in The Comics Journal. Those seeking further guidance on whether or not to buy these books should read the reviews I’ve listed below.

The central figure which unites the 10 volumes (five volumes in Japan and Asia) that make up The Times of Botchan is Natsume Soseki, one of Japan’s greatest writers. The series may be viewed as a history of the closing years of the Meiji era, a biography of various literary and political figures which emerged during those times, and a meditation on the impact of that period on the Japanese psyche.

The series as a whole was awarded the Osamu Tezuka Culture Awards Grand Prize in 1998.

Further reading:

Katherine Dacey’s review (2010). I am inclined to agree with many of the faults enumerated by Dacey, in particular the unwieldy writing and the uneven quality of the first two volumes.

Joey Manley on the first volume and translation issues (from 2006). A somewhat messy rant but he brings up valid issues concerning the distancing elements in the narrative. He also takes down Leo Tolstoy and Boris Pasternak at one point.

Derik Badman’s review (2006) of Volumes 1 and 2. Badman is a much more patient reader than Manley. He describes the general tone of these books and provides a nice summary of the various plot points.

Matthias Wivel’s review (2003) of the earlier volumes in the series (in Danish).

***

A Review of The Times of Botchan (Part 1)

by Jiro Taniguchi and Natsuo Sekikawa

Toptron Ltd. /Fanfare (B&W, Softcover)

Vol. 1: 144 pp., $19.99 ISBN: 9788496427013

Vol. 2: 128 pp., $19.99, ISBN: 9788496427099

Vol. 3: 156 pp., $19.99, ISBN: 9788496427129

Vol. 4: 144 pp., $19.99 ISBN: 9788496427136

(1) Introduction

The Times of Botchan is a historical manga concerning the end of the Meiji era in Japan. The manga begins in the early twentieth century and uses as its fulcrum and lens, the life of Natsume Soseki.

The heart of the series is neatly stated in the second chapter of the first volume and bears putting down in whole:

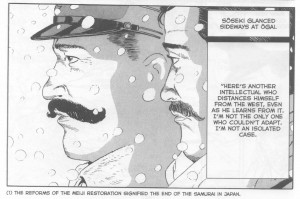

“The roots of Soseki’s illness were the same as those of the malaise of the Japanese who had awoken for the first time to consciousness about their own national identity within a modern social order and of the dilemma faced by the intellectuals, who had no choice but to learn from the West even though they hated it.”

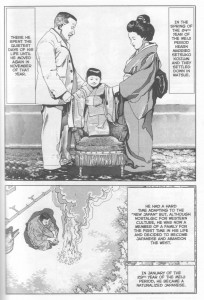

Natsume Soseki (pen-name of Natsume Kinnosuke; 1867-1916) is generally recognized as Japan’s foremost modern novelist. In the manga and to a certain extent even in present day Japan, he is the embodiment and voice of the spiritual conflicts that emerged during the Meiji period.

During his lifetime, Soseki was one of the most respected authorities on English literature in Japan. He brought the modern Japanese novel to fruition through his study of Austen, Dickens, Sterne and Swift. Yet, as the introduction to Aiko Ito and Graeme Wilson’s translation of I Am a Cat indicates, he appears to have been largely unimpressed by Western enlightenment; “throughout his career, he remained essentially and uncompromisingly Japanese.” His two years in London were wretched and his views of the English twisted by anemic social contacts. In My Individualism, Soseki writes, “To tell the truth, I do not like England very much, but in spite of this, I must allow it one thing, reluctantly: probably, in no other part of the world, are the people both as free and as policed.”

As is made clear by authors of the manga, this ambivalence was not solely restricted to Soseki. The third and fourth volumes of The Times of Botchan are essentially about the other great literary voice of the Meiji era, Mori Ogai (1862 — 1922). In his story, we find a conflict between the individuality so prized by the West and the sense of duty and honor that was fast being encroached upon in Japanese life during that period.

These volumes also take in the intertwining life of Shimei Futabatei (1864 — 1909), the author of what has been described as Japan’s first, albeit incomplete, modern novel, Ukigumo (The Drifting Cloud). His other great distinction was as a translator of Turgenev. In her commentary on Ukigumo, Marleigh Ryan quotes Futabatei as he reflects on his formative years:

“I had as my ideal in those days the word “honesty.” I wanted to live a life free of shame before Heaven or man. This concept of honesty had been nurtured in me by Russian literature, but an even greater influence was the Confucian education I had received. … The oriental Confucian influence and the Russian literary or Western philosophic influence became bound up together. To these were added an interest in socialism. From these various influences my moral philosophy was formed.”

This statement stands in contrast to Futabatei’s views on unbridled Westernization. In the opening pages of Ukigumo, for example, he describes a thoroughly frivolous and spoilt girl called, Osei, who is under the tutelage of the “loathsome” headmistress of a finishing school:

“Things went from bad to worse after she started studying English at school. She switched from a Japanese under-robe to an undershirt and adopted a Western style hairdo, strangled herself with a scarf and donned eyeglasses which ruined her perfect vision. Her self-approved transformation was perfectly ridiculous.”

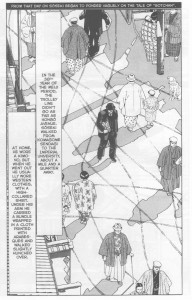

In the first volume of the manga, Sekikawa and Taniguchi provide us with some instances of this tension between tradition and modernization. Soseki is first seen potting around his house in a traditional Japanese housecoat and then clothed in Western dress as he navigates the streets of Tokyo. At one point, he is found formulating a scene for his novel Botchan in which the protagonist both physically and intellectually humiliates a European. He then suffers a bout of crippling dyspepsia when he discovers that his job as a lecturer in Tokyo Imperial University has been acquired at the expense of a noble foreigner (the irony here being that Soseki is destined to die of a stomach hemorrhage in 14 years time).

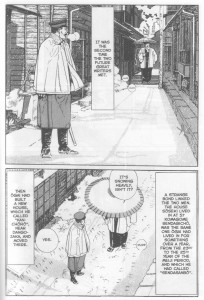

The foreigner in question was Lafcadio Hearn, the Irish-Greek writer and translator who became a naturalized Japanese citizen. He is best known in the West through Masaki Kobayashi’s film, Kwaidan, which is an adaptation of four supernatural tales from his collection of the same name. Of Hearn, Roger Pulvers in an article for The Japan Times writes:

“Even today, Hearn is considered in this country the foreigner who understood the Japanese in the most profound way. … Name a field of study of traditional art or life and Lafcadio Hearn was intrigued by it, swept away by it. He is the founding father of the school of Japanese uniqueness, the fountain that provides the spiritual and aesthetic nourishment … that Japanese people require to convince themselves that they are more than the sum of their borrowed and mechanically transformed parts.”

But Hearn was interested in the “Old” Japan, one which officials (including those at his university) were eager to put aside. This realization would come to haunt him in his later years and Pulvers quotes him as writing, “I felt as never before how utterly dead Old Japan is and how ugly New Japan is becoming. I thought, how useless to write about things which have ceased to exist.” Hearn died in 1904. Eight years later, the death of the Meiji Emperor would prompt what was perhaps the most famous act in response to this sense of passage and change.

In 1912, shortly after the death of the emperor, General Nogi Maresuke committed seppuku, ostensibly in expiation for his military mistakes and specifically for having lost his regimental banner in Kyushu during the Satsuma rebellion over 30 years earlier. His death would leave its mark on the writings of both Soseki and Mori Ogai. In Soseki’s most influential work, Kokoro, we find what may be his own thoughts in the words of one of the protagonists called, Sensei:

“I felt as though the spirit of the Meiji era had begun with the Emperor, and had ended with him. I was overcome with the feeling that I and the others, who had been brought up in that era, were now left behind to live as anachronisms.”

In his introduction to the novel, Edwin McClellan writes that, “Soseki was too modern in his outlook to be fully in sympathy with the general; and so is Sensei … however, he could not help feeling that he was in some way a part of the world that had produced General Nogi”.

(2) The Times of Botchan Vol. 3 & 4

Nogi’s death had an even greater impact on Mori Ogai, and it is this sense of nobility and responsibility that informs the third and fourth volumes of The Times of Botchan (even if the events depicted within occur a number of years before the death of the general).

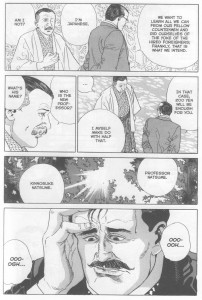

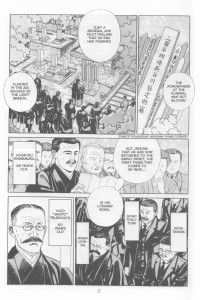

At the start of these interconnected volumes, it is 1909 and Shimei Futabatei is dead. In five years, the Meiji emperor will also have passed on and, in seven, Soseki will collapse from a stomach hemorrhage. Futabatei’s funeral is attended by some of the most famous writers and thinkers of the time, among them Soseki, Ogai and Ishikawa Takuboku, the three writers whose lives are most developed upon in these series of manga.

As with the first two volumes, this section of The Times of Botchan is also about the creation of literature. The cover description tells us that the book focuses on the relationship between Ogai and Elise Weigert, the inspiration for Ogai’s story, “Maihime” (“The Dancing Girl”), but it is also the story of Futabatei and Ukigumo.

“Maihime” was written in 1890 and has been noted for bringing “a new dimension to the literary expression of personal emotions in Japanese literature.” The story is narrated by the protagonist, Toyotaro Ota, who is the top student in his university and a civil servant of three years. He is sent to Germany to “study matters connected with [his] particular section.” At first he finds himself reading law but soon turns to the arts and history, much to the displeasure of his superiors. The opening pages of the story allow us to look deep into his soul. From Richard Bowring’s translation:

“Some three years passed. … I had studied willingly. … But all that time I had been a mere passive, mechanical being with no real awareness of myself. … I realized that I would be happy neither as a high-flying politician nor as a lawyer. … I felt like the leaves of the silk-tree which shrink and shy away when they are touched. … Ever since my youth I had followed the advice of my elders and kept to the path of learning and obedience. If I had succeeded, it was not through being courageous.”

Toyotaro’s first meeting with Elise differs little from Ogai’s own encounter in the manga. She is a dancer whose father has just died. As she is penniless, she has asked for aid with the funeral expenses from her employer who has sought to take advantage of her. Toyotaro promises to help her and produces his watch for her to pawn. Their feelings for each other deepen and soon turn to those of love. His superior is irked by his diversions and tells his “legation to abolish [his] post and terminate [his] employment.”

Toyotaro improves himself through journalistic activities and soon becomes a skilled translator. The arrival of a prominent Japanese minister in Berlin leads to an opportunity to redeem himself but he is urged “to give her up” by a friend and assistant to the minister called, Aizawa. Upon hearing this advice, Toyotaro is struck by severe misgivings: “When he mapped out my future like this. I felt like a man adrift who spies a mountain in the distance. But the mountain was still covered in cloud …”

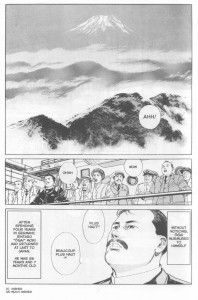

This passage from “Maihime” may be compared with Sekikawa and Taniguchi’s depiction of Ogai’s vision of Mount Fuji early in Vol. 3. To be precise, there are two visions of note at the start of the third volume. The first is that of Elise Weigert, the German dancer who Ogai has promised to marry following his four years of study in Germany — a symbol for Western self-sufficiency and exuberance. The second (the one that applies here) is that of Mount Fuji, a symbol for Japan, first glimpsed upon Ogai’s return from Germany in 1888.

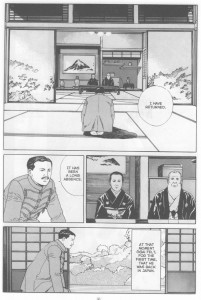

Upon the exhortation of the ship’s captain to look “higher, look much higher up,” Ogai does so only to see the peak of Mount Fuji appearing through the clouds. This image of Fuji is repeated again in a brush painting that hangs behinds his emotionless parents during his first audience with them since his return. To emphasize his point, Sekikawa narrates:

“At that moment Ogai felt for the first time, that he was back in Japan. In the country, individualism was not regarded as a personal virtue, the “family” had to be considered.”

Toward the close of “Maihime,” Elise becomes ill and discovers that she is pregnant just as Toyotaro is asked to travel to Russia to work as an interpreter. His duties “suddenly [lift him] from the mundane and [drop him] above the clouds into the Russian court.” Elise writes a loving and beseeching letter to Toyotaro and he encounters yet another crisis of confidence amidst his own joy:

“Was my passion cooling? … I thought I had discovered my true nature, and I swore never to be used as a machine again. But perhaps it was merely the pride of a bird that had been given momentary freedom to flap its wings and yet still had its legs bound. There was no way I could loose the bonds. The rope had first been in the hands of my department head, and now, alas it was in the hands of the count.”

Toyotaro, wracked with guilt, falls ill, and Elise learns of his betrayal indirectly from Aizawa even as she nurses him. She goes mad and becomes a “living corpse.” At the end of the story, Toyotaro leaves for Japan with the minister, leaving behind some money to pay for the birth of his child.

There are other links between Ogai and his protagonist not mentioned above: as with the story, the real Elise only learns of Ogai’s betrayal indirectly through his friends; the ornithological metaphor that Toyotaro uses in “Maihime” correlates with Ogai’s use of a captive bird to describe the conflict between dreams and reality in the manga. These connections are weaved into a tangle of fictions juxtaposed for effect. There are also some significant differences between Ogai’s experiences as depicted in the manga and the prose story: the Elise of the manga never becomes pregnant and her exact fate remains unknown.

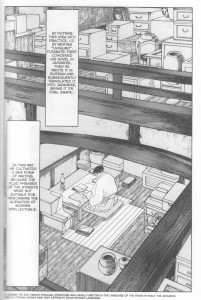

By way of short interludes interspersed between this story, we see the birth of Futabatei’s novel, Ukigumo, and the difficulties that caused its curtailment. Futabatei would later be the first to translate “Maihime” into Russian but in these early days of struggle, we see Futabatei hard at work on the upper level of a storehouse behind his father’s house. His mother, who considers his novels nothing more than storybooks, makes disparaging remarks about his chosen vocation. Ogai compares Futabatei’s mother to the calculating, shrew like aunt in Ukigumo, but Futabatei is more understanding.

Sekikawa and Taniguchi are engaged in the recreation of the world in which this famous literary work was created. On the streets of Tokyo, we see the dispossessed members of the samurai class who are the main characters of Ukigumo. As Marleigh Ryan informs us:

“By 1868 samurai were often reduced to extreme poverty. … Whether rich or poor, however, in theory at least they shared a common ethical and moral code. This has as its basic tenets a belief in loyalty to one’s family and superiors … devotion to propriety and restraint in social behavior.”

Ukigumo has as its central character a man by the name of Bunzo who lives with his aunt Omasa and cousin Osei. As related by Futabatei, “[Bunzo’s] father had served in the old feudal government receiving a stipend under it.” This feudal order had collapsed with the establishment of the Meiji era. At the beginning of the novel, Bunzo loses his job. He has also fallen in love with Osei, but his current situation puts an end to any dreams he may have had of an early marriage. He watches on helplessly as his smooth-talking, sycophantic colleague Noboru, who is also of samurai stock, inserts himself into the household with the blessings of his aunt and proceeds to seduce Osei. Of Bunzo, Ryan writes, “His are the traditional Confucian values. … It is impossible for him to yield to the fashions of his time, and, as a consequence, he is crushed by the age.”

The events of Ukigumo become a topic in Ogai’s long conversation with Futabatei toward the close of Vol. 4 in which he establishes why he cannot marry Elise. In his opinion, a life without restraints or respect for authority will leave the Japanese, in times to come, with a bitter aftertaste. In so concluding, he compares himself to Noburo who “burns with desire to rise socially” but “[holds] on to the hope that Noboru Honda has self-control and a conscience” and “will not rob Bunzo Utsumi of his fiancee Osei.” Ogai does not identify with Bunzo’s inaction and indecisiveness (the real Ogai labeled Bunzo both “anemic” and “neurotic” in an essay written many years later); rather, he has sympathy with his values and sadness.

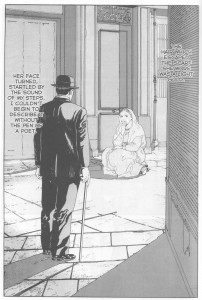

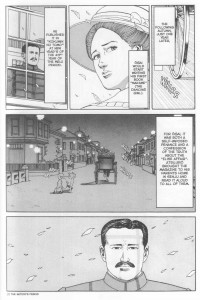

As with “Maihime” and Ukigumo, the manga reflects the triumph, hollow as it may seem to some, of giri (duty) over ninjo (emotion). By the time Elise and Ogai meet at the manga’s conclusion, their decisions have already been determined by force of circumstance. She has already booked a ticket on a steamer leaving Japan and he has already rejected the possibility of love. In Vol. 4, we see Elise’s presumably fictional adventures with a pair of lovers and assorted underworld characters. The lengths to which the young man is willing to go to free his lover from a life of sexual slavery is clearly to be contrasted with Ogai’s Old World hesitancy and reserve. Elise compares Ogai unfavorably to the uninhibited, self-sacrificing lovers she has been helping. Her experiences have shown her a Japan capable of forceful and spontaneous passions, but he can speak only of his obligations to the greater entities of family and country.

In the final pages of the fourth volume, Elise says that she can accept his reasons for abandoning her but not his lack of honesty with his emotions. In the manga, Ogai has no real answer for this. “Maihime,” on the other hand, contains a damning self-description by Toyotaro:

“If I did not take this chance, I might lose not only my homeland but also the very means by which I might retrieve my good name. I was suddenly struck by the thought that I might die in this sea of humanity, in this vast European capital. I showed my lack of moral fiber and agreed to go. It was shameless.”

Sekikawa and Taniguchi provide no hints as to which character has made the superior choice, for their struggle is merely a reflection of the conversations and debates that began in the Meiji era and preoccupy Japan to a lesser extent today.

Shimei Futabatei died in May 1909. On July 1, 1909, Ogai’s book Vita Sexualis (a thinly veiled account, in part, of his own sexual life) would be published in the literary magazine, Subaru. The issue would be banned by the authorities on July 28 and Ogai officially reprimanded by the vice-minister of war in August. Ogai and Elise’s conversation in The Times of Botchan is a counterpoint to that more fervent text, a marker on the road to the creation of a famous story and a literary master.

(Continued in Part 2 tomorrow)

This is one of those where the lack of background knowledge makes it difficult to parse the review, much less the manga. From what I’m able to glean, though, it sounds somewhat like Remains of the Day thematically in terms of the issues of repression/love/duty. Could Ishiguro have been influenced by this, or vice versa? The timings close…both late 80s….

It’s a bit like Remains of the Day but only in a superficial sense since the manga is concerned about much broader issues and the literary and artistic climate of the times. You’re right about the manga and the review – it’s mainly for those who have already read the comics and want to know a bit more about what they’ve read.

Pingback: Jiro Taniguchi Manga Moveable Feast Begins! » Manga Worth Reading