This pertains to the quotation which you provide from Crumb in which he states that he:

“…went back and checked against the text and it’s not in there. And they claim to be honoring the word of God, and that the Bible is a sacred text… the most significant thing is actually illustrating everything that’s in there. That’s the most significant contribution I made. It brings everything out.”

Or as you elaborate in your own words:

“Crumb’s work explores and attempts to reconstruct the cultural life of Genesis as a literary, historical, and spiritual work on its own terms…..The original audiences for these tales had an understanding and shared context that we have lost. Crumb subjected the text to a rigorously close reading and made a solid attempt to visualize the largely conjectural cultural setting (laying out his methods, which I haven’t heard anyone challenge, in the introduction.) His adaptation must be regarded as an experiment, in painting a full picture from a collection of hints, and such totality cannot have the exactness of scholarship.”

And later:

“If you adhere to the view that theology is critical for a true engagement with the text, then Crumb’s scene-and-character-sensitive construction of a credible world from Scripture alone- with the help of modern Biblical criticism- more on that later) clings to the letter in a crude, childish, even insolent way…..What’s dangerous about treating any depth in Genesis as if it lies in the theological edifice of later times is that, if the critic isn’t up front about the values he’s bringing to bear, it can sound very much as if he’s saying that a treatment that fails to engage with that edifice isn’t engaging with it on levels we commonly understand literature to have.”

The “unfortunate” circumstance with which we are faced here is that Genesis is a religious book. As such, it is incontestable that the finest minds who have worked on Genesis though the ages have been of a religious disposition. If we are to understand Genesis on both a superficial and deeper level, the issues presented by these individuals must be grappled with and developed upon or rejected to better effect.

Further, what we find in these statements is a needless conflation of theology with scholarship which must be rejected unless by “theology” one means archaeology, the application of linguistic skills and the study of textural information. As I’ve said in my original article, I’m not demanding any form of spiritual engagement from Crumb even if this severely restricts his options as an artist.

Knowledge in our present age is rarely built from the ground up but on “the shoulder of giants”. I would suggest that the study of literature in its highest form always engages with the “edifice” of earlier times. That this edifice was mainly constructed by scholars with a religious bent might make it painful for the atheist to traverse, but it is possible to divorce oneself from these theological overtones; there is much modern scholarship which is undertaken from a perspective which is secular, non-traditional and disinterested

Scholarship steps in where context is lost to bring forth the text. It would be impossible to “reconstruct” Genesis on “its own terms” unless one fully understood what those terms are. Far better to suggest that Crumb’s Genesis was built largely on the author’s own modern sensibilities as filtered through a smattering of research; that is, largely on his own terms. This brings him closer to your point: that he was able to “bring out subtle parallels, irony, and humor difficult for the modern reader to grasp” and that he had a…

“…deep involvement with the identity and journey of the characters. He had to create likenesses for them and live deeply in their stories to make their journeys credible, etching each face and detail in monkish isolation.”

This is in fact where Crumb’s comic succeeds best. The Book of Genesis is a secular construction based in reality (at least, as far as the text allows). Crumb’s skill as a draftsman does not elude me nor does his talent for depicting human physiognomy. I have already remarked on his proficiency with adaptation as well as his attention to detail in my original article though, perhaps, not as forcefully as you would have liked. Alex Buchet and Ken Parille have elaborated on this fleshing out of events in their own remarks; this skillful placement of characters into a stained world of the ordinary. You add to this by advising us of the “staggering wealth of quotidian detail”, “the moral stamp on each face in the headshots” which “give the genealogies a weight that is hard to analyze but ridiculous to deny.”

To which must be appended the question of whether this is a satisfactory alternative to the wealth of ideas on the text which have come down to us through the centuries. The answer in your case and, perhaps, in most readers’ minds would be “yes”. For those who wish to see comics moving beyond the act of drawing and simple adaptation into a full intellectual and philosophical engagement with the text, the answer can only be in the negative. Matthias Wivel tells us that “art is art, not theory (or theology)”, but should art not be based on superior ideas as well, especially when these ideas are so thoroughly engrained in the text?

The act of approaching and envisioning Genesis as literature is time tested and well trodden. As you put it:

“…Crumb’s adaptation is thoroughly in the letter. But the lack of effort to unify Genesis with later tradition hardly means that his handling has no moral, psychological, intellectual, or spiritual- in other words, literary- interest. It is strange that an alert, sensitive, and rigorously faithful adaptation is being treated as if it must lose all the “subtext and power” of the original, and be devoid of any deeper engagement.” and later, “A literary endeavor can often teasingly resemble a religious one, because so many of the ways we relate to literature are descended from religion.”

As children and adults through the ages will attest, Genesis read purely as a story has a power all its own. It is at this level that many religious Jews and Christians engage with Genesis; sieving through the psychological and ethical depths of the figures who populate the text. But what you see as “subtext” is merely the first layer of a work which has inspired authors for centuries.

It is perhaps telling that you find a straight reading more engaging than one further illuminated by interpretation. To read Genesis as only story and narrative is acceptable but not praiseworthy. The same might be said of finding one’s own path through the text while ignoring all other avenues of engagement. It would be as if someone worked out a simple algebraic proof by himself, which is fine as it stands though one should not expect a significant degree of adulation from those who have moved beyond this level of inquiry. While it may be desirous for a student to work out equations in such a manner, to ignore the much greater work which has been done through the ages can only be accounted arrogance in the extreme, especially when the final product carries so little intellectual weight.

Of tangential relation to this and on the issue of juxtaposing classical art with Crumb’s comics, Jeet Heer argues that I should have been more mindful of the “historical differences between the early 21st century and previous eras” and that my original post was “bluntly ahistorical and unresponsive to the way comics work as comics.” I would suggest that Jeet reexamine his own antiquated ideas when it comes to art and comics. This is an age where art is no longer shackled to the dictates of the church, where even laymen have at their feet a surfeit of knowledge concerning these religious texts, and where we have come to appreciate concepts as much as skill. What has been placed before us is literal, disregarding of erudition and appreciated best by readers displaying a sharp preference for craft over ideas. If paintings of a certain antiquity are placed alongside Crumb’s images, it would not be to merely highlight a difference in skills, but also to suggest that a comic of our times should be able to move beyond the restrictions of drawing and painting to achieve even greater richness in terms of form and content.

At the end of your article you state that “Crumb’s work can serve to cut through the arrogance of modernity and captivate a reader who would be likely to dismiss the text itself as an irrelevant artifact”. I don’t believe I have ever denied this and if we were to engage with The Book of Genesis purely at this level, I do believe that there would be very little left for us to debate; condescending as this approach would be to Crumb, comics in general and to modern readers without religious affiliation. Now you might say that this is “dismissive of the beginner, or the person who might find Genesis easier to enter through a work like this”. It is not. My original critique was targeted at a very particular readership, one whose focus is not solely on a comic’s utilitarian aspects. My approach was simple, I gave the comic a level of respect as was appropriate for a book by one of the most celebrated living cartoonists. You seem to have understood this as you contend that:

“This set Suat to assessing whether it “could not be ignored” in connection with art and literature surrounding the Bible- raising the bar quite high, since most believers don’t even read the Bible from cover to cover”

This is precisely my intention; to appraise Crumb’s comics in the context of all art and at the highest level. Some will think that my reservations concerning Crumbs comics amounts to a wholesale rejection of it. This would be a mistake. Rather I am attempting to place its achievements in the proper context within the entire spectrum of Western art and intellectual thought. This may seem like a silly endeavor but it is a point which is often lost when discussing comics. It is not “hostility” “to a faithful adaptation” which you detect, but an attitude which demands more from art beyond a careful transcription which fills in the logical lacunae; one which insists that the text speak beyond its human drama and one which seeks to understand the nature of that primal strangeness and mysticism which is tied inextricably to the narrative. One artist will see and describe the beautiful ripples on the surface of a lake while another will move beyond this and look beneath the surface and see life. It is the latter artist and his approach which I treasure the most.

I want to take issue with this statement: “The ‘unfortunate’ circumstance with which we are faced here is that Genesis is a religious book. As such, it is incontestable that the finest minds who have worked on Genesis though the ages have been of a religious disposition. If we are to understand Genesis on both a superficial and deeper level, the issues presented by these individuals must be grappled with and developed upon or rejected to better effect.”

This might be true until the 18th or 19th century: i.e., before the rise of modern secularism when priests and rabbis had a virtual monopoly on intellectual life. But for the last two centuries there have been many, many intelligent commentaries on the Bible from a non-religious point of view. I’ll note that Robert Alter identifies himself as being ethnically Jewish but isn’t a believer. One could also make note of the forays into Biblical criticism by Zizek, Eagleton and Badiou, none of whom are orthodox in any meaningful way. So again, the question is: why should Crumb be required to pay attention to any particular sectarian reading of the Bible? Why shouldn’t he be free, as all of us are, to simply read the text and rely on secular scholars like Alter to help clarify the more obscure passages?

Suat didn’t say “orthodox” though. He said “of a religious disposition.” I think that definitely would include Zizek and Eagleton, both of whom couldn’t be much more immersed in theology, and are clearly passionately interested (even in Zizek’s case obsessed) with the nature of God despite (because of?) their atheism. Alter too clearly has a serious interest in theology, whatever his beliefs.

The issue with Crumb that Suat is pointing out is not that he’s not a believer, but that he simply doesn’t seem to care all that much about the text in particular, or about the Judeo/Christian tradition in general. Suat isn’t asking that Crumb pay attention to any particular reading; he’s asking that there be an interest in Genesis beyond a surface gloss of the text. That interest doesn’t have to include religious belief (as Eagleton and Zizek show.) But Suat would like it to include a “religious disposition” — that is, a sense that religion matters, that the questions it asks and attempts to answer are vital, that the theological tradition is valuable and worth engaging with. Suat doesn’t see that in Crumb.

And nobody else really seems to see it in Crumb either. The responses to Suat have been basically, “Crumb shouldn’t have to care about that stuff, why are you saying that he should?” There’s not actually a disagreement about what this project is doing I don’t think; there’s a disagreement about whether the progject is worthwhile, or how important it is.

Jeet: There is absolutely nothing to stop this. As I clearly state in my response, “there is much modern scholarship which is undertaken from a perspective which is secular, non-traditional and disinterested.”

On the other hand, I would be very surprised if Alter chose to ignore every interpretation from antiquity in favor of his own, thus creating a point of view which was wholly of his own making. It is far more likely that he would have read all viewpoints and developed upon them or even accepted prior interpretations as the most likely. The real question is just how much of this process we find in Crumb’s adaptation, the level of intellectual engagement we find in the images and sequences he presents us with.

Well, if we’re willing to say that an explicit athiest like Zizek has a religious disposition, then the same is true of Crumb, who describes himself as a gnostic and definately believes in the existence of a spiritual realm outside of material reality.And Crumb’s spritual/mythical interest is a longstanding feature of his comics, going back to the psychedelic images of the late 1960s and forward to his adaption of Philip K. Dick’s mythical experiences.

Maybe I’m reading too much into the phatic implications of Suat’s posts, but he does seem to me to be playing a game of Christian identity politics: Crumb is not part of the tribe, so he shouldn’t comment on “our” sacred book. But the Bible belongs to everyone, not just Christians.

The Bible does belong to everyone. And an individual’s spirituality and interpretation can be as leaden and half-assed as that individual wishes. Whether or not we find that spirituality or that interpretation compelling is another matter. In any event, I think if you suggested to Eagleton or Zizek that Crumb should be taken seriously as a theological or religious thinker on the basis of his vaguely defined belief in a spiritual realm and some psychedelic imagery from forty years ago, they would laugh so hard it might even take them, like, ten seconds each to refute you.

I think there’s some identity politics going on, but I would hesitate before attributing them to Suat. Secularism has its own tribal affiliations these days, after all.

@Suat. Well, if you compare Crumb’s book with Alter’s notes (not just Alter’s translation but also his exegetical comments), you’ll see that Crumb looked at those closely. And since Alter’s notes were built on a reading of many earlier (largely rabbinical) sources, Crumb’s interpretation grew out of a much larger exegetical tradition.

But really, I want to question the dichotomy being set up here between deep, spiritual readings (assumed to be good) and secular surface readings (held to be bad). It seems to me that when you are dealing with a difficult ancient text, one valuable approach is to try to figure out what the surface reading is. Trying to read a text “spiritually” is often an excuse for ignore the meaning of words and doing the hard work or philology and historical reconstruction. While Crumb does, as I’ve noted above, have a spiritual side, what is admirable about his adaption of Genesis is that he also tries to grapple with the dense materiality of the words themselves, to figure out what they say about the world of the Bible, how people looked and what the Biblical world was like. The same is true of Crumb’s other adaptations ( of Boswell, Dick and others): he tries hard to link words with plausible physical representations: he is a materialist reader, and deserves praise as such.

@Noah. Crumb’s spiritual concerns can be seen in many of his comics. The attempt to find a meaning for life outside convential material reality is a fairly major theme in Crumb. Crumb is not a religious believer but he is a spiritual seeker. Over the course of the last few decades he’s done thousands of pages of comics, most of which are easily available. You should try acquainting yourself with his larger body of work.

I think it would be worthwhile to separate out the two oppositions (it’s actually not just one dichotomy) and to treat deep/surface independently from secular/spiritual.

You can have both deep and surface secular readings just like you can have both deep and shallow spiritual readings.

Jeet: Haven’t I praised Crumb sufficiently for his abilities as a “materialist reader”? If I deny that The Book of Genesis is a work of genius, it does not follow that I consider it poorly wrought in every single way. I would assume that what we see in Crumb’s adaptation – the settings, the clothes, the faces – are the product of a combination of research, conjecture and the imagination. This effort is admirable from the standpoint of pictorial adaptation but I feel that the text demands much more from the artist.

A “surface reading” could be religious and spiritual as well but it would still be a “surface” reading, and I would still be dissatisfied with it. Similarly, a “deep” reading could be wholly secular in nature; probing the moments of frank religiosity about what they say about humanity and its needs; piercing the symbols and how they came about and asking penetrating questions of the actions of the characters which populate the tale.

Jeet, every time I try to read Crumb (especially recent work) I get irritated and bored. The last thing I tried was his Kafka book, which I found incredibly uninsightful and wrong-headed. My objections were much like those of Suat’s to Genesis; that is, Crumb’s lack of imagination and unwillingness to engage with others’ viewpoints left the text a drab testament to his usual concerns, a litany of Crumb tropes rather than an effort to say or think anything in particular.

Lots and lots and lots of people consider themselves spiritual seekers. As Caro says, that doesn’t necessarily mean they have a deep engagement with religious thinking, just as atheism doesn’t mean that such an engagement is lacking. And an insistence that one must read more Crumb to appreciate him adequately doesn’t seem to at all obviate Suat’s point, which is that this Genesis is best appreciated by those who already have a vested interest in the artist.

Jeet, when you say this “Trying to read a text “spiritually” is often an excuse for ignore the meaning of words and doing the hard work or philology and historical reconstruction,” would you include spiritual readings that focus on metaphors, such as, say, John Milton’s, as somehow “ignoring the meaning of words” and not “doing the hard work?” Or do you just not consider that a reading?

I think Milton certainly “reads” Genesis for us in Paradise Lost, but he is mostly unconcerned with what’s literally there. But Milton is not “illustrating” Genesis: does the idea of “illustration” for you entail, or at least prioritize, a literal reading rather than an interpretive one?

I don’t think this is really about reading protocols: you can end up tarring the entire history of spiritual “readings” with the brush of less educated and/or highly politicized modern readers. Just because Crumb lives in a world where a lot of people have enough literacy to read the bible literally, but not enough to read it metaphorically, that doesn’t automatically mean their limitations also limit him…Paradise Lost may be a product of its time, but it is also an object in ours.

Caro, where does Jeet say that? Is it from another thread?

Also, I should say — thanks for coming by to talk about this Jeet. I’m glad the issues Alan raised were engaging enough for you to want to throw your hat in the ring as well!

It’s in this comment. Number 6 above.

And yeah, three cheers for Jeet coming by! HU needs virtual cocktails so we can buy him one.

There was an interview with Crumb on one of the public radio shows in which he said that a lot of the clothes came from classic Hollywood. I guess that’s research.

Ouch.

Have you noticed how big budget historical films are getting incredibly accurate lately? Since I love history it’s candy for my eyes. Really a delight. Until a few years ago I could always guess in which decade the film was made (usually the women’s hairstyle gave the film away). Not anymore…

I couldn’t care less for these films though…

Sorry for being out of topic; please ignore my remark and carry on…

I wasn’t that out of topic, then?… My in topicness went in the opposite direction of my off topicness which, come to think of it, makes a lot of sense.

Excellent point, charles — a point that anyone who argues that Crumb’s work involves deep historical research and understanding must face.

Here’s a passage or two from the New Yorker website, which outlines some of Crumb’s sources:

‘[W]hen Crumb began work on “The Book of Genesis” …, [Peter] Poplaski brought over his copy of D. W. Griffith’s 1916 silent film “Intolerance.” Crumb was so impressed with its colossal Babylonian gates and attack scenes, he wished aloud for film stills he could reference….

‘He [Crumb, or possibly PP on Crumb’s behalf] scoured flea markets and discount bins for copies of Cecil B. DeMille’s “The Ten Commandments” (1923 and 1956), William Wyler’s “Ben Hur” (1959), and a made for TV Samson and Delilah starring Dennis Hopper as a Philistine general. He also turned to some less predictable Hollywood sources—Bernardo Bertolucci’s “The Sheltering Sky” (1990), Martin Scorsese’s “The Last Temptation of Christ” (1998), and Stephen Sommers’s “The Mummy “(1999) and “The Mummy Returns” (2001).’

There is nothing inherently wrong with a literal visual interpretation. But it is a point against any work that frequently relies — as Crumb’s often does — on visual cliche and cultural shorthand.

This is especially the case for a work that presents itself in terms of its fidelity to a text and its sources — and even more for a work that it being defended as a serious pieces of visual exegesis.

You know, I actually find the fact that he’s relying on Hollywood for his imagery kind of charming. I guess because it’s funny, and also because it ratchets the stakes and the pretension down. It puts it back in the Classics Illustrated category, which makes comparisons to great Western artists or issues of interpretation largely moot.

I don’t know that it renders them moot so much as it makes it a problem of the criticism rather than the work. People still aren’t saying “look at Crumb’s sweet little illustration job.”

The Hollywood reference adds a layer to what I was getting at in my question to Jeet: if illustration (as stated on the book’s cover) = Classics Illustrated (in this case), then under what circumstances is it ok (with Alan, Jeet et al.) for a critic to say that the choice to do an illustration job is a timid choice for an artist of Crumb’s stature?

Your Kafka comment really needed a link to this.

I suppose I’ll have to defend Crumb in the absence of his apologists. It must be said that the gates of Sodom look nothing like the incredible sets for Intolerance. The more’s the pity. They look like a modification of the Ishtar gate of Babylon, adjusted for size and splendor of course.

Yeah, I’m with you, Noah.

Thanks for doing the virtual legwork, Peter.

Using historical source material like film stills and stuff dug up of flea markets, though, doesn’t necessarily make a work materialist and literal.

Kim Deitch does that all the time, and makes it into magic. (Although Noah will disagree.)

I should add that most reviewers who defend The Book of Genesis as visual exegesis are largely unconcerned with costuming or architectural fidelity. They cite the quality of the bodies, their posture, facial expressions and actions – the word made flesh as it were.

In a superb critique of the Biblical analysis of Northrop Frye, Robert Alter made a fundamental objection to the habit of some (not all) Christians who read the Hebrew Bible allegorically to find evidence of Jesus buried everywhere in the text. I think Alter’s comments go to the heart of the dangers of spiritual readings of all sorts: “The revelatory power of the literary imagination manifests itself in the intricate weave of details of each individual text. On occasion it can be quite useful to see the larger frameworks of convention, genre, mythology, and recurring plot shared by different texts. The identification of overarching patterns was Frye’s great strength as a critic, enabling him to make lasting contributions to the understanding of genre and literary modes. But the real excitement of reading is in the endless discovery of compelling differences. In the nineteenth-century novel, a Young Man from the Provinces may be the protagonist of a whole series of books, but Rastignac is not Raskolnikov, nor is Flaubert’s Frédéric Moreau just a Gallic version of Dickens’s Pip. The specificity of sensibility, psychology, social contexts, and moral predisposition of each is what engages us in the distinctively realized world of each of these novels, whatever the discernible common denominators. The Bible, as a set of foundational texts for Western literature, is an exemplary case for the fate of reading. Through centuries of Christian supersessionism, Hebrew Scripture was systematically detached from the shifting complications of its densely particular realizations so that it could be seen as a flickering adumbration of the Gospels that were understood to fulfill it. This is hardly a reading practice we want to revive, either for the Bible or for secular literature.” (Robert Alter, “Northrop Frye Between Archetype and Typology,” Semeia #89, 2002).

Deitch is fairly explicit about what he’s doing though, right? There isn’t a pretense to historical accuracy — quite the opposite. He’s locating the “magic” of the tschotkes (sp?) in his/our interpretation and nostalgia. It’s precisely because these bits of cultural detritus provoke a reverie that he’s interested in them; he loves interpretation.

Crumb seems to be privileging literalness though, which makes the Hollywood sources seem like a problem (though, to be fair, from the assorted comments I’ve seen, and just in general, it’s kind of hard to parse what exactly Crumb thinks he’s doing and why.)

“The issue with Crumb that Suat is pointing out is not that he’s not a believer, but that he simply doesn’t seem to care all that much about the text in particular.”

Noah,

I don’t see this at all. Crumb made 1000s of decisions based on the text (and a number of translations) and consulted differing traditions of biblical scholarship. He may not feel about Genesis the way you want him to, but it seems pretty clear that he cares. I think Alan’s careful analysis shows this.

In a way far less compelling than Alan, I tried to show that Crumb’s decisions are consistent with an overall philosophy toward the material, one made visible when you show how his choices set him in dialogue with and against familiar ways of portraying scenes in Eden, for example.

People seem to take Crumb’s words overly literally: “He says he approached it ‘as a straight illustration job,’ therefore it can’t be any good.” I think a better method would be to ask analytical questions, for instance, “What are the significances — the “ideologies” — behind his decisions as they manifest themselves in a given panel, sequence, page, chapter, section of text, etc . . .?” — the kinds of questions Alan asked and answered. You could just as easily say that because Crumb approached it as “an illustration job,” he shows a reverence for the text that embellishers and abridgers fail to: He takes Genesis seriously by tackling every verse and visualizing it.

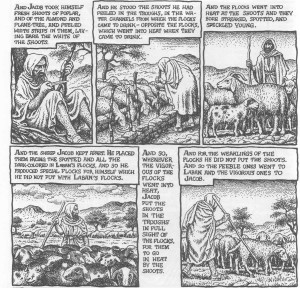

Literalness takes many forms. Crumb’s literalness is manifested in a few different ways: 1) his choice to rely heavily on Robert Alter’s very literal translation 2) his decision to depict everything in the text and not alter the text as other cartoonists had done before him and 3) his decision not to put an allegorical overlay on top of the text (as many Christian artists before him had done).

A different type of cartoonist might have tried to be literal by trying to depict the clothes and housing as accurately as archeological knowledge allows. But that’s not the type of literalness Crumb was aiming for.

I don’t think Crumb’s goals are so hard to parse out. He’s been fairly open about what he’s trying to do.

“Deitch is fairly explicit about what he’s doing though, right? There isn’t a pretense to historical accuracy — quite the opposite. He’s locating the “magic” of the tschotkes (sp?) in his/our interpretation and nostalgia. It’s precisely because these bits of cultural detritus provoke a reverie that he’s interested in them; he loves interpretation.”

Crumb’s pretty explicit too. He tells us about these sources in his introduction.

I don’t know, Jeet. That seems like an argument for historical specificity and accuracy, not against engaging with the Bible as a spiritual work.

As an example, as long as you brought up Zizek: his central point, or reading, of the Christian story is that Christ’s death means that God is dead; therefore he sees Christianity central truth as atheism (he kind of follows Shaw in this, I think.) That’s a spiritual insight, (albeit an atheist one) — it engages with the text in the context of various theological traditions (as I said, Shaw, also Chesterton, Hegel, etc. etc.) in order to form an overall spiritual/theological idea about its essential meaning.

In fact, I think you could see what Alter is critiquing there as a *failure* to do a deep reading (spiritual or otherwise). The problem with these Christian exegesis is that they engage the text *literally*, in a surface way. They read it as presentist allegory, rather than as symbolic truth (or falsehood, as the case may be.) He is in fact accusing them of doing exactly what Crumb is doing — taking a word for word approach, filtering it through their own idiosyncratic and instinctive prejudices, and coming up with a message that illustrates the text rather than understanding it.

Concerning the Alter quote: How does this help us Jeet? A Christian interpretation is only one among many and, in the eyes of a lot of readers, as open to acceptance and rejection as any other (secular, Jewish etc). The real question is whether Crumb made any choices in his interpretation outwith the prosaic. An aesthetic impasse as far as I am concerned.

“This is especially the case for a work that presents itself in terms of its fidelity to a text and its sources — and even more for a work that it being defended as a serious pieces of visual exegesis.”

It’s easy to overstate the issue of realism and then use it against Crumb. His work is equally — and intentionally — cartoony, too. If he was strict about “fidelity,” he wouldn’t draw gigantic sweat beads . . .

He has a kind of fidelity to the text, but it’s modified by and filtered through his cartoon sensibility.

Hey Ken. I think that’s a really good point, and one which raises some useful questions. Particularly — is the cartoon sensibility especially useful or appropriate for this kind of exegesis? Is the form Crumb uses part of a thematically coherent take on the text? Or is it just a kind of default shrug; a decision to treat everything like a nail because all you have is a hammer?

Alan’s defense of the book, it seems to me, doesn’t really take the cartoonishness into account; he is mostly defending it on grounds of literalness and physicality. But, as you say, the literalness and physicality is of a very limited sort, it’s filtered through a “cartoon sensibility.” But what is that sensibility doing? It’s not plainly satirical or farcical (a standard use of cartooning.) So…what’s it there for? What’s it doing?

From a recent interview of Crumb (http://www.rcrumb.com/aboutcrumb_hey.html):

Robert: Some people were disappointed that I didn’t do a sendup of it — my own scathing take on it. I fooled around in the sketchbooks with those ideas and I just, I didn’t like how it was working out so I just decided to do a straight illustration job of it. It seemed to me that the original text was so strange in its own way that there was no need to do any sendup or satire of it. My trial efforts to do that seemed lame, it wasn’t working out.

Alex: So as you got more into the book, did you sort of approach it as a historical project?

Robert: Yeah kind of. I mean, the text itself is so lurid and barbaric, you don’t have to alter the text, you can just illustrate as accurately as possible the text as it’s written. Somewhat historic, but its not real history. But, you know, it is part of history, but in and of itself it is myth. It’s legend. It’s stories with all the same elements that modern storytelling uses to keep people spellbound. It’s the same kind of thing. Except for the priestly aspects like the “begots,” and all those tedious and legalistic passages. But, as far as, like, how people react to my version or… I said in a lot of interviews that I had no idea when I was doing it how people would take it. I knew that probably some of the Crumb fans — it’s really true here in France, even more so in Germany — it didn’t sell well at all in Germany — a lot of the Crumb fans were very disappointed because it wasn’t this outrageous takeoff. I had no idea how they would take it. And you know, people ask me if there’s been a lot of hostile reactions from religious people and I really haven’t gotten much of that. I got invited recently to come to the San Diego Comic Con. There’s some Christian comic fans that have a conference every year and discuss, like, spiritual aspects of comics. And they wanted to invite me, they wanted to have a panel about Genesis. And the guy that wrote to me, his name is Buzz Dixon. He said that not all Christians are happy with my version of Genesis. And I wrote back to him, I said, “I’m very curious, what do they object to?” I have no idea what they object to. I’m just doing a straight illustration job there. I’m curious to see what he’ll write back.

——————

It would seem, from the above, that Crumb approached Genesis with a faintly hostile attitude that would preclude the spiritual.

I conjecture that he was then “taken” by the power of the text.

About the Hollywood stuff– so what? Renaissance artists didn’t hesitate to clothe Biblical figures in Renaissance raiment.

——————-

Kim Deitch’s name has come up. Has anyone else seen his charming adaptation of the Book of Job?

Like all such things, I would look at Crumb’s cartooniness on a scale; it’s applied in differing degrees at different places. Much of the facial portraiture (especially in passages that illustrate a series of faces) seems sedate and less cartoony, a dignified way to introduce these characters.

Elsewhere Crumb uses a stock cartoon device — a halo of lines that seem to emanate from a character and then fade into the black background (this emenata is distinct from the spiritual halo) in a way that’s also not parodic and certainly not literal.

It’s an artificial “lighting” device with an emotional and even, at times, a primarily spiritual content – nearly every time this device is used it’s an addition by Crumb – the text of Genesis doesn’t tell us about the light source for each verse and scene . . .

“Alan’s defense of the book, it seems to me, doesn’t really take the cartoonishness into account; he is mostly defending it on grounds of literalness and physicality.”

As I mentioned on another thread, I think that Crumb’s cartoon pen line is an inherent part of his philosophical take — his interest in physicality, in the coarse textures of the garments, the visceral intensity of many scenes, etc . . .

Kim Deitch is fantastic. Just being in the room with his books makes me happy.

I haven’t seen Job, but I’ll look into it.

=======================

Jeet’s quote was, I’m guessing, in response to my question about metaphor, because Alter’s essay is a criticism of Frye’s reading-in of metaphors into the text. I’m going to take it that way and Jeet can tell me if I’m wrong.

I don’t think, Jeet, that it actually answers my question though, which was about Milton, not the Bible (or Crumb, directly, although it’s en route to being about Crumb).

Milton, unlike Frye, was not attempting to explain what the Bible says. He didn’t claim to be doing a “close reading” or criticism or scholarship or exegesis. It seems like you’re saying Crumb’s project is basically the same as Frye’s: to tell us what the Bible says. And that Crumb, unlike Frye, follows Alter’s idea of how this should be done, which is a good thing.

But the history of the literary Bible is a history of interpretive, metaphorical readings like Milton’s — not like Frye’s (see quote below). Frye, like Crumb, claims that his text merely reflects what is “in the text”, but the “literary Bible” is made up of the generations of metaphorical readings and extrapolations and inspirations made in the millenia since the original Biblical text was written. Those readings are found in all those other texts, like Milton’s, like Blake’s that Suat originally compared Crumb’s work to — not necessarily in the Bible. They take the Bible as inspiration, not source.

Absolutely Crumb doesn’t claim to be doing Milton’s project. But is it not a valid criticism to say that Milton’s project is artistically more ambitious and valuable than Crumb’s project, even if Crumb executed his flawlessly?

That’s what I hear Suat saying: not that Blake (etc.) are more accurate than Crumb, but that they are more artistic.

As a statement about Biblical scholarship, especially about the influence of Frye on Biblical scholarship, Alter’s point is very apt and well taken. But I don’t think he’s intending it to apply to derivative imaginative works: that’s your extension, yes?

It’s hard to see a middle ground here between “Classics Illustrated” and “derivative, imaginative work.” It seems from your spirited defense of Crumb that you think there is a third term in there, an imaginative, artistic work that is neither derivative nor “mere” illustration.

It seems to me that’s what everybody’s arguing about — whether or not Crumb actually does anything particularly artistic with that third term. Is the strength of his craft enough to elevate something admittedly very conceptually simple to the status of art?

Which leads to my follow up question: when are literary critics “allowed” to find a work wanting for its lack of imagination — even if the complaint is with the author’s choice of approach rather than his execution? Or are you saying that literary critics can never critique an artist’s approach to material?

For people who don’t have access to Alter’s essay, I’ve quoted a passage below that I think is particularly illustrative with regards to the kinds of metaphorical reading Alter is objecting to. He’s not talking about literary writers taking a text as inspiration, or about critiques of their success in interpreting: he’s talking about literary critics saying the Bible says things that they don’t have evidence for.

===========

Here’s the passage from Alter (same citation as Jeet’s):

Suat (et al.),

I believe that the “embodiment” you describe is about more — and has been described as being about more — than just bodies.

The building, the costumes, the trees, the tools are all part of this embodiment. Crumb takes these narratives and places in them in “the world.” Unfortunately, this vision of the world often seems much less innovative and much more recycled than Crumb’s supporters are suggesting.

But even if we just stick to faces and bodies – Crumb’s bailiwick — do we not see many of the same problems? I think we do.

Personally, I *love* those genealogical passages, where each name gets a face. Those portraits seem varied, gentle, suggestive.

However, much of that variety and subtlety fades in many of Crumb’s drawings of Genesis’ main characters, many of whom are drawn in various forms of the same glowering face.

Look, for example, at the images of God near the end of your first post. The “creating” God (Gen 1:1), the “warning” God (2:17), the “calling” God (3:9), the “cursing” God (3:17-9), the “worrying” God (3:22) — they all look like variations on a theme, the cliched visual theme of the stern and scowling patriarch.

(And this same physiognomy and attitude gets recycled in countless other characters, especially Abraham. How many of Crumb’s characters seem to have inherited God’s forehead, brow, and eye-sockets? Is this his interpretation of the Imago Dei?)

These faces did not all *have* to look this way. There is no reason they all had to share a scowl — or even be scowling (see Crumb’s other images for examples).

Can Crumb differentiators effort and concentration from concern and anger? Why did he choose to use the same wrinkled-brow iconography when the Lord was calling out “Where are you”? Why the same angry eyes when God is deciding to send Adam and Eve out from Eden — a moment that happens one panel *after* He as done something very gentle and “embodied” for them (making their clothing)?

Crumb is making these visual and narrative choices — and the choices are usually predictable and all-too familiar (even from the surrounding pages). He could have shown God making the animal skin coats: the text says it happened. He could have had God’s pre-expulsion face show more concern or regret — but he uses the old pattern instead. He could have had shown a difference between the God who calls out to Adam (“Where are you?”) and the God feels betrayed by and then curses Adam — but he didn’t.

Perhaps this is all intentional. But that argument requires some very special pleading — especially when the book’s defenders are counting on its visual subtlety, especially when it comes to matters of bodies and faces.

(And please tell them not to look at God’s pointing hands when he is first cursing the serpent and then Adam. Odd embodiment, indeed. And why all the pointing anyway? Is that a shorthand way — no pun intended — to act out scolding and cursing? “YOU, and YOU, and YOU!”)

Again, there are wonderful, subtle, and unexpected moments in Genesis (Alan has shown us many). But the “ideas” of the comic and the means of expression are, just as often, common and repetitive — even when it comes to Crumb’s “embodiments,” great and small.

My comment above does not mean to imply that we cannot take Crumb’s visual choices seriously. IN fact, I want to take then very seriously — even, and especially, when I think those choices are uninspired.

Another example interests me: the Abraham and Isaac story. Crumb’s visions of Abraham are not terribly powerful, in my opinion. Again, he uses and reuses many versions of the same expression. And that strange and static shot that closes the scene is especially wanting: bug eyes, sweat shower, that oddly raised “cleaver.”

But that does not make the subsequent panel any less wonderful. The image of Abraham saying (once again) “Here I am” is as vulnerable and suggestive as almost anything else in the book. It mixes worry, reverence, concern, even childishness. A very full moment.

But doesn’t it make many of the other images of Abraham — here and elsewhere — fall a bit flat?

Another odd choice, possibly worth mentioning: Crumb shows Abraham and Isaac riding back *together* after the binding. But the text doesn’t; it only mentioned Abraham. Isaac disappears for two chapters, reappearing as a marriageable man living in a different region.

Why did Crumb give us a scene of paternal reunion when the text refuses to do so. And more importantly, why did he make so little of that choice?

Alter is right to point out how images are often forced to “show” what the text can elide. Crumb creates new questions — adding something that the text does not provide — but does nothing with them.

To clarify: when I quote Alter in comment #26, I was responding to Suat’s earlier comments about the merits of a spiritual response to Genesis, not to Caro’s comments about Milton. Of course imaginative artists can be as spiritual as they want (or don’t want)

Peter,

I see that passage differently. Abraham’s expression in those panel shifts from showing fear and puzzlement at what he is asked to do, to sad resignation, and then revealing a menacing embrace of the task — I see an emotional narrative in his facial expressions, a narrative that slowly and carefully develops across three pages. His expressions play off of those of his son, who cries in one, and later has a truly odd and unexpected look of acceptance (not indicated in the text) as he is about to be cleavered.

“Another odd choice, possibly worth mentioning: Crumb shows Abraham and Isaac riding back *together* after the binding. But the text doesn’t; it only mentioned Abraham. Isaac disappears for two chapters, reappearing as a marriageable man living in a different region”

Maybe I am misunderstanding something. The text says “Abrahman returned to his lads, and they rose and went together to Beersheba.”

But Jeet – regardless of whom you were responding to, the fact remains that Alter’s critique wasn’t of imaginative responses to Genesis, it was of scholarly ones.

It still sounds like you’re saying to Suat that he shouldn’t expect Crumb to be imaginative, that the standards for scholarship apply instead of the standards for art.

Noah: “Alan’s defense of the book, it seems to me, doesn’t really take the cartoonishness into account; he is mostly defending it on grounds of literalness and physicality. But, as you say, the literalness and physicality is of a very limited sort, it’s filtered through a “cartoon sensibility.” But what is that sensibility doing? It’s not plainly satirical or farcical (a standard use of cartooning.) So…what’s it there for? What’s it doing?

“[T]rying to tell potent stories with the tools of jokes [?][…] trying to write a powerful, deeply engaging, richly detailed epic with a series of limericks[?]”

Even the “straight illustration job” part of this is odd. Crumb says he’ll give use the Bible word for word…but what is the Bible? For him (oddly) it’s King James. This choice is the most cliched of choices–the most well-known, the most iconic. Similar to the choice of old white-bearded God. As a “straight illo job” Crumb props up the oldest, most institutionalized, most conservative version of the Bible. His reluctance to “Crumb” it with savage satire, etc., is consistent with that. Daring, rule-breaking, troublemaker Crumb is not in evidence here…to the confusion of many.

If anything, this project seems like “Crumb getting old.” Insofar as his anti-establishment side was what earned him his name and reputation, this project is stunningly incongruous.

As a draftsman, Crumb remains amazing…but I don’t find a whole lot that’s interesting in his Genesis other than that.

I was wondering when people would finally start making fun of his Hollywood reference. Here’s Crumb from his introduction:

“Pete Poplaski… [provided] me with an enormous amount of source material to work from, including hundreds of photos from Hollwood Biblical epics [freeze-framed from the screen]… Roger Katan was also very helpful with visual source material. It was he who compelled me to go back and correct some of the artwork on the earlier pages after he laughed at how I had drawn the clothing, which he said looked like modern bathrobes, and how the tents looked like they came from a sporting-goods store… I had a lot to learn. Katan grew up in Morocco and was very helpful with the details of everyday life in the pre-modern world of his childhood, and, having a professional interest in indigenous architecture in North Africa, lent me books full of photos of strange, “Biblical”-looking cities, people wearing robes and using implements that hadn’t changed over millennia.”

And from the Paris Review:

“I developed a great respect for Cecil B. DeMille. When you freeze-frame it and look at it closely, every detail is really interesting. You’ve got these donkeys pulling primitive carts with big urns all tied up with ropes, and I used all of that. All the statuary, the rows of lions as you come out of the city of the Pharoah. It’s beautifully made and all the craft and attention to detail, it’s really quite remarkable.”

“And did you get history books about the beginnings of Christianity?”

“You have to go way back, to the beginning of Mesopotamian civilization, because the stories of Abraham and all that- that’s like 2000 BC. It’s hard to find Mesopotamian visual imagery that goes that far back. How did people dress? Did they have doors? Did they have a door on hinges, or what? The Bible says, Lot closed the door and wouldn’t let the men come in, but what’s the door made of?”

To consider how serious this was we’d have to have an idea of what kind of research DeMille’s people employed. But Crumb’s “Mesopotamian visual imagery” is an understatement. Even if you had more than the barest archaeological traces, then you’d have that anachronism between the time of the events and the time of the storytelling that Homer has- but you’d never get close enough for that to be a problem. You have to base any visual treatment on whatever is as close as you can get to that world. If Crumb is a fool for using Hollywood- who themselves were facing these problems, and doing some kind of research- where were the more accurate reconstructions he should have been using?

I posted this point in the other thread but I want to scream it when I read this discussion:

“…far from following his instincts in the woolly way that Suat described, his choices were informed by a serious analysis of the text, and supported by scholarship- Robert Alter’s commentary, which, if you’ve seen the book, is extensive, in-depth, and synthesizes the insights of a variety of fields of scholarship.

“Crumb’s choices are thoroughly founded on the information in Alter’s commentary. This is a major feature of Crumb’s book that I don’t think I’ve seen pointed out anywhere, and I should have described it more clearly.”

Eric, I’d love to hear what you think about the Alter essay Jeet quoted: specifically the bit that is summed up in the last sentence. Earlier in the essay, Alter insists that literary reading (the imaginative reading proper to poetry) has to be separate from critical reading (which tells us what literature is). It’s an interesting insistence, for several reasons. It does successfully rehabilitate the Hebrew Bible from Christian readings (what he calls “Christian supersessionism”). But it also ignores the fact that for writers, literary reading is the first step that allows an artist working with a source to be “inspired” by it, to see all the places where (s)he can do those “interesting” things.

If we followed Alter’s model for reading all secular literature as well as the Bible, like he says we should in that last sentence, then we would never have had Milton, or Blake, or Dante because they first read the Bible the way Alter says we shouldn’t, and then crafted their reading into an imaginative derivative text.

If everybody read like Alter says we should, all we’d have are books like Crumb’s Genesis. No Paradise Lost. No Dante. And no other literature either, because imaginative inspiration depends first on reading and then on putting that reading down. Creativity starts with imaginative readings.

As terribly over-the-top as Frye is in many ways, the idea that artists might look to Alter’s absurdly materialist way of reading instead, honestly is going to give me nightmares. It’s bad enough when critics approach art this way…

Eric, Crumb used Robert Alter’s translation, not the King James.

Caro, Alter’s review of Crumb’s book points in a fairly different direction, I think. In fact he specifically argues that the Bible demands imaginative interpretation (at least, that seems to be what he’s saying.)

I think Alter’s review of Crumb focuses more on “intentional” ambiguity, though, the stuff that gets “concretized” and resolved in a (conventional) graphic novel.

His sense of the play of interpretations still seems constrained; I think Alter’s ethics of reading is sort of a “next generation” New Criticism: very close reading, with rich historical context, but without the “literary” context that characterized the original New Criticism. I don’t think the review is ultimately irreconcilable with the essay Jeet cites.

While he certainly sees comics as inherently limited in a way that fiction and painting are not, I think he also sees the need to put some textual constraints around reading prose (or reading period) as well…

Re: the commentary: Sorry, now I see Jeet mentioned it. I guess I got my objection from the article.

Peter, I may have made too much of the pointing, but I was contesting Suat’s claim that Crumb showed no awareness that the name Adam comes from “adamah,” ground or earth. It’s obvious from the way Crumb stages it that he knows God is naming him in that panel (“for dust you are, and to dust you shall return!” And in the next panel, he’s Adam for the first time.) I don’t see how he could have made it plain to the reader without a footnote, but he does reinforce the theme of working the ground.

Suat:

I should say that my essay really needed to have a line to the effect of: “I’m going to attempt to describe the framework that I think Suat is bringing to the table, and I invite him to improve on it.” I had meant to do that. It’s rude to just describe somebody’s religious perspective for him.

But I’m reminded of why I needed to separate your approach in order to defend Crumb’s work effectively. I have to read your posts very slowly & with a text program open to keep track of my objections to each line. I’ll try to summarize and say something- as a comment, not an essay- if there turns out to be anything new.

Suat: A point I didn’t bring out in my essay is that an adaptation founded in modern (historical, literary) scholarship is itself an answer to theological scholarship. I don’t know if I could get you to admit that they have utterly different assumptions behind them, but that’s the best place I could imagine more debate on this going. I respect the view you offer in your last lines, and your sincere statement. I hope this hasn’t been too difficult. Maybe if you come back to the comic in a few years it will look different to you. I do plan to read Augustine sometime.

*****

To be honest, I struggled much longer trying to respond to this perspective than I did in forming a statement on Crumb’s achievement. I thought this strain of criticism needed to be answered promptly. I don’t have the command of history that Jeet Heer does, or much at all, and I’m gratified and humbled that he appreciated the job I did. It would have been much better if I had focused more on the book, but I hope I managed to set the discussion about it in a better direction. I think anybody who’s trying to assess it has to do more work than usual, analogous (on a far smaller scale) to Crumb’s.

What struck me about the reaction to this book- from everywhere- is how hard people seem to find it to really look at it. Everyone connects through a reference point that doesn’t seem helpful. Crumb is known for being dirty, so this is a bawdy artist at odds with a spiritual work. Comic book scholars have a highly refined edifice of ideal comic art- you use silent panels (talk, look at the clouds, talk more,) you snip off the narrative anywhere that you see it overlapping the action, and you keep the drawing symbolic and open so it will be filled with the reader’s imagination. I saw one critic sputter that he doesn’t think there are any silent panels in the whole thing. The amount of observation, thought, and literary statement that went into each drawing should, I hope, quietly revise people’s ideas in the coming years.

When I look at parts of this comic I loved, it’s the lines of dialogue that rise to the front- they sound in my head. That’s the poetry, but Crumb supported it and took it there. When you go back to Alter from the comic it’s shocking just how sparse the narrative is, and easy to forget just how much Crumb is filling in while you’re reading.

I guess I’m skeptical, still, about this prevalent idea that a great adaptation has to do something very bold and abstract. That needs more defending. I am not one of these people who gets mad about anachronistic performances of Shakespeare, but the “this is not your Dad’s…” approach that has completely taken over does lose something when you don’t see the milieu. Lear talking about how he and his daughter will live in prison and laugh at the gilded butterflies of the court doesn’t connect as much if you haven’t seen that style, and world, during the play. I am obviously way behind you fellows on my Bible adaptations, but Pasolini’s Jesus film was somehow very exciting for me because it was so dead on, and so real. In this case, I just don’t think drawing God as a huge jellyfish would have done anything but bring Crumb to mind.

And the point I keep wanting to make is, if it’s so unchallenging for us not to want to Crumb to rewrite the book, why are there so many of those efforts? In repeating its uniqueness, I’ve been trying to make the point that that itself demands a serious effort to appreciate. We’ve seen people write between the lines of the Bible forever… and boring, celebrated comics come out all the time, if that’s what this is about. The fact that people, not just religious ones, seem to find this so hard to take suggests to me that there’s something here.

Alan: Textural and historical analysis is the basis of all biblical scholarship whether it is taken from a religious or secular perspective. The difference between these two approaches is not at issue here. From your essay and Jeet’s comments, I get the impression that you sense that any opposition to Crumb’s comic comes from a religious perspective and not an aesthetic one (i.e. my disagreements are voiced solely from a theological perspective). I can only say that this is not the case and that these perspectives are easily separable, and that I find both secular and theological perspectives stimulating and challenging as a reader. I do believe that this is the source of your disapproval in encountering my critique but I can say no more than what I have already stated. If Crumb had decided to adapt Proust, I would have made exactly the same demands of him.

As Caro tries to explain above, my preference is for an adaptation which makes choices that are aesthetically pleasing on both a pictorial and intellectual level. The pictorial component of this equation has proven quite subjective. Ken, Jeet, Alex, Matthias and yourself find it deeply moving and invigorating; Noah, myself and some others not at all. I can only speak for myself but it is a very honest reaction; one I could certainly put into words but to very little benefit at this point in time. The purpose of this conversation as far as I am concerned is not to change minds but to allow me to see from the another perspective (among other things); to listen as others put into words that “beauty” which I cannot apprehend.

As for myself, I can only return to the same question which I have reiterated in various forms throughout: Is there any level of serious intellectual and philosophical engagement with the text beyond the expressive and reactive figures which populate Crumb’s comic? If it is there, I can only say it is rather poorly expressed. A scholar like Alter hardly comments on it and is left to remark on the work as if it were confined to the medium of drawing and illustration. I can hardly blame him since Crumb as he stands today is hardly known for his formal innovation or exceptional authorial skills. Alter is left grasping for “ideas” to tackle in his review but he does not find this disturbing because he expects no more from a comic adaptation.

There is perhaps the notion that a secular (atheistic, agnostic) engagement with Genesis can only be at the level of a superficial literary reading (this is in fact the view I find in the opening paragraphs of your essay), but this thought must be rejected in the face of all the evidence to the contrary. In my original essay, I presented a number of avenues of approach both secular and religious. If there were a preponderance of religious interpretations in analyzing Genesis chapter 2 and 3 surely you must realize that this was due to the frankly mystical nature of those chapters? You will also notice how this ratio reverses itself once we get to the discussions of Dinah and Shechem. An adapter needs to wrestle vigorously with the whole concept of a “god” and Crumb does not; he merely acquiesces and transcribes. The questions and choices were vast (what is the “fruit”? what are the trees? what is this “god”?) but Crumb chose poorly.

My conclusion has remained largely unchanged in this respect, and it is that The Book of Genesis is a superficial reading of the text or at least one which lacks intellectual weight. Let me assure you that I do not find any happiness in this assessment since I would much rather read a masterpiece than a merely competent comic.

But if you’re adapting something that was culturally nearer (and not intended for it) like Proust, if you don’t come up with a personal response the question of why you’re doing it is more serious.* Alter focused on Crumb’s solutions to mysteries for a reason.

(*With movie adaptations there seems to be almost the expectation that a great novel will get the attempt. Hollywood is imperial. This would be closer to a writer doing a novella-length reworking, unless it came across mainly as an art book.)

As for Introducing Kafka, wasn’t that originally part of that whole publishing line of guides to famous writers? It was better, and deserved the spotlight, but he was still illustrating Mairowitz’s survey on the writer. I didn’t see that as one artist grappling with another- appreciating, yes, and introducing.

There’s a direction in which discussions of this can’t go unless they turn into questions about the Bible, like whether Jacob has a character arc. I don’t think this automatically means that the best original novels we have in comics are superior; and doesn’t the kind of reworking people want come close to something like Faulkner’s Absalom, Absalom? That is, if you want to see a personal struggle with the Bible, why even have names like Shechem, and a setting nobody remembers. Write what you know. But this gets into the same problem of evaluating it on different terms. It’s not a novel. It’s not Kierkegaard, either.

We get back to the same problem of a reluctance to take it on its own terms, and the the conviction that a kind of work we’ve never seen before is completely unnecessary. The only response I can imagine is “there’s a reason,” but justifying that would require a close look on the terms of a line-by-line visual/dramatic adaptation, not a tour through the interpretations of the Garden of Eden that Crumb doesn’t mention.

Your style can be justified as a question about its greatness, but that can only be determined after a careful look at what it does. I think I missed a lot. I will agree that a graphic novel about the Garden of Eden would need to dwell more on what each part means. As for God- this will set people off if anything will- the more interesting approach, more than yet another artist struggling with “what is God,” is scraping away those efforts and uncovering what the figure meant at the time. That takes seriousness, respect, and the picture emerges from clues. The Bible, I might add, is not about the nature of God, but the story of a people’s relationship with God.

That expectation that everybody has to start from that same premise: “taking the work on its own terms” (by which everybody means basically the terms the author intended) gives this conversation a really polarized quality that wouldn’t be there if that wasn’t the expectation.

The problem with that assumption is that the only overall evaluation it can lead to is success or failure: “the author succeeded at doing what he tried to do” or he didn’t. The space for creative engagement with a work of art is opened up dramatically if you don’t assume that you have to take it on its own terms but allow yourself to bump its terms up against your own.

For me at least, it’s not “a reluctance to take it on its own terms” — I haven’t written about it yet because I’m reading through it carefully trying to do just that and it’s slow going for me because I’m not really enjoying it. It’s pleasurable enough, but it’s not interesting.

The reasons I don’t enjoy it have a lot to do with the things Suat talks about: it’s not intellectually stimulating. They have a lot to do with the things Alter talks about in his review: the ambiguity is evacuated. The richness of the text becomes limited by the pictures, and the payoff of the pictures — although differently — isn’t equivalently rich and surprising.

That may be a reluctance to engage the text on its own terms, but there’s an equal and opposite reluctance to acknowledge that not all choices and goals are equally artistic, imaginative, or valuable. There’s a reluctance even to ask the question of what that means and how you tell.

“We get back to the same problem of a reluctance to take it on its own terms, and the the conviction that a kind of work we’ve never seen before is completely unnecessary. ”

I have to say, having read the book now, I find your take on it more or less completely baffling in just about every regard, Alan. The idea that this is a kind of work we’ve never seen before, for example…Crumb’s work seems to fit quite easily into the Classics Illustrated tradition — more pretentious, more literal, sure, but not different in kind. And I see no, nil, nada, negative effort to uncover what God “meant at the time”. Instead, I see cliched visuals, simplistic readings, and an occasional energy inspired by moments when the text happens to dovetail with Crumb’s long-established interests (i.e. the female body.)

“Taking it on its own terms” seems to mean acquiescing that (a) Crumb’s project here is a priori interesting or worthwhile, and (b) comparisons with other artists who have tackled the same subject matter are not allowable since they didn’t do exactly the same thing Crumb did. With (a) I just have to disagree, and (b) seems to be deeply confused about the nature of comparisons, which are always of things which are like in some way and unlike in others.

I don’t know…I hope to write at more length on this next week…but I think overall the book eschews any kind of concept conceptual matter almost entirely . The question then becomes whether Crumb’s style (its physicality, its cartoonishness) and the commitment to historical literalness are themselves sufficient to carry interpretive weight.

As I’ve sort of indicated, I think this dovetails in interesting ways with the major fascinations of comics criticism at the moment, which tend to focus on formal skill and historical analysis to the detriment of more analytic readings. Which is why I think the conversation about this book in particular is worth having….

Caro: Well, you start with “what was he trying to do” and then you go to “what is the significance of that.” Relating to your earlier comparison, can’t we say that Paradise Lost was the work demanded by the time? That’s not just to dismiss it as a product of its time.

This version could be taken as a hammer to certain religious constructions, and an answer to people who are still using the Bible to claim authority, but it’s also a dramatization of the religious attitudes of its people. With mixed feelings, but some sympathy- though I don’t think those feelings are even the most important aspect.

Alan, that’s still an objective, scholarly/historical/textual approach to reading the book. It’s not bumping up his terms against mine (or any other reader’s.)

It’s reading from and for authority — the authority of the text, of the author, of history. It’s limited. It’s not BAD. If it’s what excites you you should do in spades and write about it with as much passion as you can manage.

But it is not the only way to read.

“Crumb’s work seems to fit quite easily into the Classics Illustrated tradition — more pretentious, more literal, sure, but not different in kind.“

Ha! Well, I used a quote where Crumb was talking about the difference between this and Classics Illustrated treatments. Here’s a part I chopped from my essay for length:

”The style of that class of comic adaptation of any work I’ve seen is to summarize, bowdlerize, and squeeze out every drop of flavor to create essentially its own “classics adapted” genre that bears no resemblance to what the young reader who luckily follows through will often find to be the magnificent strangeness of the original.“

Noah:”And I see no, nil, nada, negative effort to uncover what God “meant at the time”“

To put it more sharply, how about ”a portrayal of the relationship?“

Noah:”Instead, I see cliched visuals, simplistic readings, and an occasional energy inspired by moments when the text happens to dovetail with Crumb’s long-established interests (i.e. the female body.)“

See, that’s where we get to my point that people only seem to connect with it through opinions they already have about Crumb. I know him a shrewd observer of human nature- the guy who drew Fritz the Cat, for instance, greedily drinking in every second of his appearance on TV, on a talk show saying, ”Now these kids these days, I think have something to say.“ Anybody who’s posted to a message board and hit ”refresh, refresh“ should recognize that. Also for his complicated spiritual interest- the point of the Mr. Natural comics are not ”Mr. Natural is a fraud“-he isn’t- but to portray the spiritual seeker, in Flakey Foont, as a total narcissist. And yet he sees himself as one. With this work he’s expanded his range of observation and emotion in ways not even his boosters expected.

I know I’ve stated my impressions of the book as thoroughly as I can. I will try to participate only when I have some response that moves the conversation forward. I am thinking about what people have to say.

Yes, Eric’s point that Genesis is incongruous with Crumb’s body of work seems to me ignorant of just how varied Crumb’s examination of people and how they behave has been over the past decades.

Transgression has always been only part of a much wider register with him, and increasingly so from his early collaborations with Harvey Pekar, through his blues biographies and adaptations of Boswell, Dick, etc. to recent autobiographical work such as the masterful “Walking the Streets”.

Genesis totally makes sense as part of his artistic development.

Hey Alan.

Yeah, the Crumb quote…to see the problem with the Classics Illustrated approach as a failure to include enough of the text seems fundamentally misguided to me.

“Crumb’s work seems to fit quite easily into the Classics Illustrated tradition — more pretentious, more literal, sure, but not different in kind.”

Crumb’s is a version of a classic text in comic form, just like CIs are.

Crumb’s is fundamentally different than every CI I have ever read; it is not abridged.

So, it is and is not different in kind; it all depends on how you define the categories into which it can be placed.

“more pretentious, more literal”

I understood you to have argued that, in his literalism, Crumb has no pretensions to anything, and that that was your problem.

“I think overall the book eschews any kind of concept conceptual matter almost entirely .”

Not only does it eschew any kind of concept but any kind of “concept conceptual matter”! And it still manages to be pretentious.

No, alas, literalness in comics does not currently parse as unpretentious.

Abridgment is, to my mind (at least in this case) a quantitative rather than a qualitative difference. I understand that the books defenders disagree though.

It would help if you explained what you mean by pretentious.

Maybe talk about a scene or some aspect of Crumb’s approach that is pretentious.

I was going to edit “concept conceptual matter” after I posted — but then I figured it would be unfair since others can’t correct their comments. So good catch!

Pretension is in part about what claims the book makes for itself, and which others make for it. The jacket, the promotional material, and many critics (and to some extent Crumb himself) claim a lot for this book.

It is a little weird because, as you indicate, the book itself, removed from all of that, actually doesn’t demand or seem to seek comparison to great art — it seems happy being a long classics illustrated mostly. I still probably wouldn’t like it much as that (making classics illustrated longer doesn’t improve them especially), but I probably wouldn’t feel the need to argue about it.

Noah said, “Yeah, the Crumb quote…to see the problem with the Classics Illustrated approach as a failure to include enough of the text seems fundamentally misguided to me.”

You don’t see any other kind of objection in my quote about squeezing out the flavor? That was me, I don’t know if that came through.

Caro wrote, “Alan, that’s still an objective, scholarly/historical/textual approach to reading the book. It’s not bumping up his terms against mine (or any other reader’s.) It’s reading from and for authority — the authority of the text, of the author, of history.”

I don’t commonly deal with that style of discourse, so I’ll say it my way. I think a review must attempt to understand what a work is trying to be. It can and should also address what the critic or anybody else will get out of it. It can fail at that first part, but must make the attempt.

Likewise, the modern scholarly view of these writings that some of us have been defending is that determining as best we can what they were intended for is critical. We can still have our own response, in our own time, and still work their pieces into our own great mosaics of ideas, along with the notions of days when the focus was on defending them as having authority and prophecy outside of time.

I guess you do miss some creativity in interpretation when you don’t shear a writing from its context and purpose, but you lose so much else when you do. It’s not fair to the work. Yes, it’s funny how this connects right up to your recent dust-ups.

With Suat, since I think you’re suggesting I’m squeezing out his perspective, I will summarize. I don’t object to his feelings about the work. I suggested a kind of essay that I thought could handle them more appropriately. I objected to a review that treated the book as being flat for not engaging with levels he is certain are there and are superior, and for talking about it in a way that conflated them with any kind of level deeper than mechanical transcription. He is now saying he never denied the levels I described in Crumb’s work, though these were covered under terms like “flat” and “childish” in his review. I don’t find his claims that Crumb could have had an intellectual atheist response convincing, since this book could easily serve as one. He still shows total certainty about the hierarchy of these levels, and the authority of those centuries of scholarship, which is fine; all we can do is clarify that.

“You don’t see any other kind of objection in my quote about squeezing out the flavor?”

I think this is pretty much case by case. My favorite Classics Illustrated (not that I’ve seen a ton, but still) is probably Sienkiewitz’s crazed expressionist reworking of Moby Dick. Dropped almost all of the text; might not even be 1/100 as long as the original. Nonetheless, it’s not at all flavorless.

I think Crumb’s Genesis is pretty bland myself.

Hmm… yes, I liked that too, but that’s not what we, or you, mean by the Classics Illustrated tradition. That’s an artist’s personal response, from the return of the brand in the 80s. Use that to beat Crumb with if you like, in fact it’s a solid counter-example, but that’s not what you mean when you describe Genesis as being in a Classics Illustrated style.

Well, the point is that how much or how little of the text you use isn’t necessarily related to how interesting or powerful the resulting comic is. I think the whole question of completeness is a red herring, basically.

Hi Alan:

Some of this may have to do with the range of critical writing outside “reviews”; you say “I think a review must attempt to understand what a work is trying to be,” and yes, I think that’s probably true. But a critique can be something other than a review: it can be an analysis, or an interpretation, or a response.

You also say this:

“I guess you do miss some creativity in interpretation when you don’t shear a writing from its context and purpose, but you lose so much else when you do.”

Did you read my post from today on Henri Langlois? I think it’s interesting that you feel like the greater loss is from shearing the work. To me that is very specifically what profoundly original artists like Godard do. Jog’s comment referencing Histoire du Cinema provides the best example, since many of the films that show up in that work are sheared from their context and purpose, and all are at least loosened.