Few comics in the last year have elicited as much critical attention as Robert Crumb’s The Book of Genesis Illustrated. Most of these notices have been positive with a number of publications affirming Crumb’s status as a cartooning god. Such has been the adulation that even the most ardent Crumb enthusiasts no longer clamor for more recognition but are now asking for deeper and more contemplative readings of the comic. Consider Jeet Heer in a recent post at Comics Comics:

“As I’ve mentioned before, I’ve been disappointed by the critical response to Crumb’s Genesis book. It is not so much a matter that the book hasn’t won enough praise, but rather that the critics, with a handful of exceptions, haven’t had the intellectual resources to tackle the challenge presented by Crumb’s handling of the Bible. Ideally, the critics of the book should be well-versed in both comics and Biblical scholarship.”

Heer’s statement suggests that Crumb’s book is of such learned complexity that only individuals of the greatest experience and intellect would be able to do it justice. Suffice to say, I found this statement to be at odds with my own experience with the comic which I felt offered more superficial pleasures.

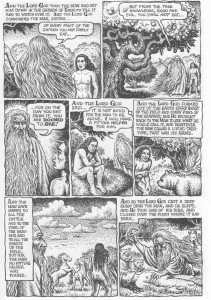

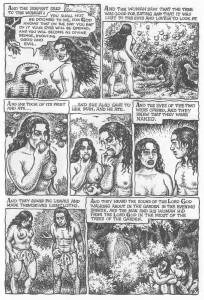

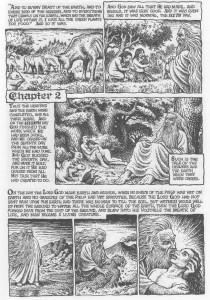

In order to ascertain the truthfulness of this and various other statements in praise of Crumb’s comic, I’ve decided to examine his handling of what may be the two most famous chapters in Genesis, namely chapters 2 and 3 which concern the creation and fall of man. The importance of these two chapters in the context of Judaism and Christianity is such that their substance is widely known even by those with only a cursory knowledge of Genesis. They have also been the subject of innumerable explorations and appropriations in art, film, poetry and literature. These factors will make the ascertainment of the extent of Crumb’s achievements in The Book of Genesis that much easier.

***

In some recent blog comments, Heer advised his readers that “Crumb was performing exegesis through his adaptation and thus is part of a long tradition of Biblical commentary”. In another posting he writes that The Book of Genesis “deserves to be seen not just as an important work of art but also a significant commentary on the Bible.”

Of course, such an adaptation could not be anything else. For one, the practice of illustration itself presupposes the act of interpretation [exegesis: from Greek, from exegeisthai to interpret, from ex-1 + hegeisthai to guide]. The artist must provide expression, posture, dress, setting and reaction where the text is silent. He may even choose to provide a useful contradiction between word and imagery if he is so moved. We see this in the plethora of considerably less elevated Bible-related adaptations Charles Hatfield lists in his survey of a Genesis exhibition at the Hammer museum. Secondly, as the noted scholar, critic and translator, Robert Alter, states in his initial comments on Crumb’s book in The Nation:

“I stress that it is an interpretation, because the extremely concise biblical narrative, abounding in hints and gaps and ellipses, famously demands interpretation.”

Rather, the issue at hand here is whether Crumb’s adaptation of Genesis is “significant”, that is a work which cannot be ignored in any consideration of the art or literature connected to the Bible.

To be sure, the bulk of the praise extant has dwelt upon the artist’s reputation and his distinctive execution. Henry Allen of The Washington Post can hardly contain himself at the thought that the pope of impiety, political incorrectness and hedonism has decided to take on the Bible and God. Alter embraces this as well and has the following to say about the opening verse of chapter 2 of The Book of Genesis:

“Perhaps the most winning aspect of Crumb’s Genesis is its inventive playfulness… God’s resting on the seventh day of creation is shown by his sitting with his eyes closed, fatigued, his back against one of the trees of the Garden, while naked Adam and Eve in the background cuddle together in sleep.”

The scene is, of course, not so subtle satire; a reimagining of that unblemished garden as a kind of Disney cartoon (and every bit as ridiculous and fictional) with Bambi, Thumper and Faline in attendance.

____

____

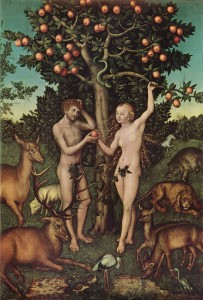

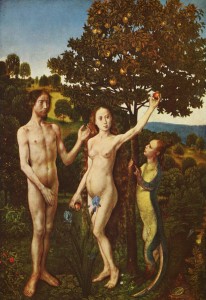

[Left: Bambi and Faline; Right: Adam and Eve by Lucas Cranach the Elder; note the Christian iconography with the stag representing Christ]

The woodland creatures who espy the sleeping creator bear comparison with those which surround Snow White in her most popular incarnation. This gently mocking tone reasserts itself periodically throughout Genesis.

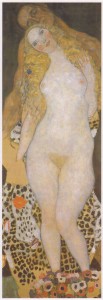

Crumb’s oft cited depiction of pure sexual disinhibition towards the close of chapter 2 is another example of this frolicsome spirit which in this instance seems almost self-referential in its longing.

[Gustav Klimt’s Adam and Eve (unfinished)]

[Fritz Comes on Strong”, 1965]

[Cave Wimp”, 1988]

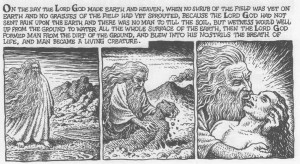

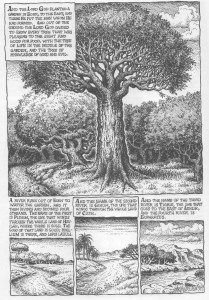

As for the artist’s rendering of the creation of Adam, it has some similarities to that found in Basil Wolverton’s The Bible Story, a connection elaborated upon by Charles Hatfield at Thought Balloonists.

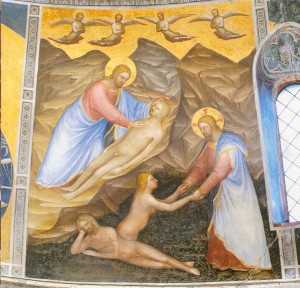

This solution was not an uncommon one during the Italian Renaissance, here made fresh by showing the stages in this act, in particular the breath of life given to Adam (the word “breathed” or “blew” here suggesting the intimacy of a kiss). Crumb’s adaptation is also notable for showing Adam in his clay-like state, a reminder of the Egyptian (see The Hymn of Khnum and Hekat) and Mesopotamian (see Enki & Ninmah, and Bel) myths which carry the same motif.

[The creation of Adam and Eve, Giusto di Giovanni de’ Menabuoi]

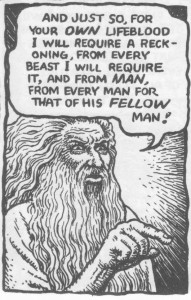

[Elohim created Adam (1795), William Blake]

As articulated in his short commentary found at the end of The Book of Genesis, Crumb is particularly interested in these ancient tales of creation and periodically inserts them while neglecting to emphasize the many internal consistencies, dilemmas and word plays in the Biblical narrative. Thus, for example, the “dirt of the ground” is linked to pagan tradition and not to a play on the words “man” (adam) and “ground” (adama) where “man is related to the ‘ground’ by his very constitution (Genesis 3:19), making him perfectly suited for the task of working the ‘ground,’ which is required for cultivation…his origins also become his destiny” (Kenneth A. Matthews).

The stated “literalness” of Crumb’s adaptation as well as its generally bland imagery will lull many readers into the false impression that Genesis intends a deep consideration of centuries old biblical scholarship. It doesn’t, an important point which I will address in more detail later.

What follows is God’s prohibition and warning concerning the consumption of fruit from the tree of knowledge. The Lord’s brows are knit, his figure towering over Adam. It is interesting to note the number of times Crumb portrays God from this standpoint in his comic; that of a person standing at the edge of reality who seems of human proportions, but who then takes on the space and terrifying air of something other worldly when provoked.

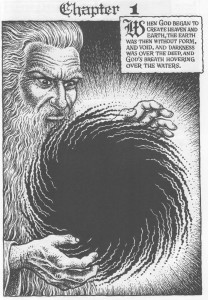

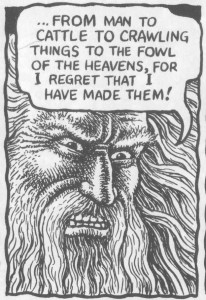

There is the instance of God’s act of creation…

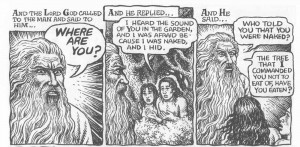

…his anger as he calls to Adam & Eve who are seen hiding in some shrubbery…

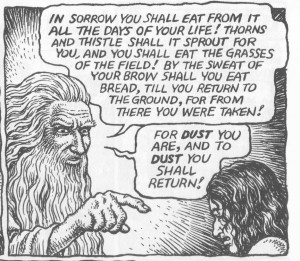

…his curse on the ground and Adam…

[Genesis 3:19]

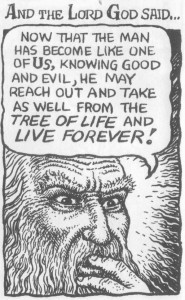

…his cogitations concerning the ambitions of man…

…his decision to invoke the great flood…

…and his sanction against murder.

In explication of his choice to so portray the Almighty, Crumb writes:

“After closely reading the beginning of the Creation, I suddenly imagined an ancient man standing on the shore of a sea, and gazing out at the horizon, and seeing only water meeting the sky.”

Much criticism has focused on Crumb’s use of the traditional image of a bearded old man to depict God. There are certainly glaring problems with this. For one, it conjures up all kinds of unflattering comparisons to his artistic forebears.

It also conveys an all too facile understanding of Adam being made in the “image of God” (imago dei), whether this is rooted in the theories and debates surrounding the terms “likeness” and “image” (e.g. in the writings of Irenaeus and Thomas Aquinas), the existential and relational readings of Karl Barth or the functional readings which altogether dispense with the idea that the “image” must consist of non-corporeal features (i.e. the “image of god” as seen in man’s dominion over the earth and animals). This is but one indication that Crumb’s journey through Genesis was more personal and instinctive than cerebral.

Hence we have Marc Sobel’s complaint that “part of the problem [he] had with this adaptation [was] the overly literal interpretation and the complete lack of insight about the actual ideas underlying Genesis:

“Thus, the depictions of God as an old man, the creation story, etc. that you [Derik Badman] commented on represent a very childish understanding of Genesis. That would be fine if this were a children’s book, but the problem is that, by presenting the entirety of the dense text… no child will be able to penetrate this book either. Thus, its an interpretation doomed to disappoint any potential audience other than fans of Crumb’s art.”

On the other hand, some might argue that Crumb’s portrayal of the creator (fleshy, interactive and emotional) is an acknowledgment of the capricious Mesopotamian gods the artist is so enamored of. Crumb had the following explanation concerning his approach in his interview at Vanity Fair:

“I had several different approaches to making God. One was a tall thin man with no beard and another was a young looking man with long straight hair that looked more like an angel than a god. He had pupil-less eyes that were beaming light. But I decided to go with the standard, severe patriarchal God. It just felt like the right choice. That just seems to be what the God of Genesis is all about. He’s older than the oldest patriarch.”

Crumb’s almost anti-intellectual approach to Genesis continues to pose difficulties throughout the rest of these two chapters.

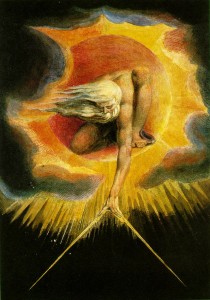

While few would question the rigor with which the tree of the knowledge of good and evil is drawn, it remains at best only a fruit bearing tree. One might view the central image of the tree of life (many branched, filled with knots and ramrod straight) as a representation of the masculine ideal and the tree of knowledge in the background as the curvaceous and deadly feminine, but there is little beyond this to recommend it.

What we don’t find in these illustrations is any evidence of the speculative richness the idea of the tree of knowledge has evoked through the ages; be they the ideas concerning sexual awareness proposed by Ibn Ezra, the capacity for moral discrimination, the granting of paramount knowledge or the bestowal of a divine wisdom. All that we find in The Book of Genesis is a personal mythology influenced in sections by the somewhat discredited theories of Savina Teubal (which I should add is still preferable to the alternative of unthinking transcription; see R. C. Harvey’s summary of this as well as another feminist perspective).

In much the same vein, the encounter with the serpent in Genesis chapter 3 is reduced to a flaccid conversation with a walking reptile. Adam is absent throughout this version of events, though the presence of the plural form of “you” in 3:1-5 suggests he is with Eve but not deceived like she is. Crumb sticks to his vow of straight illustration, refusing to explore the reasons for Adam’s acquiescence despite his absence from the serpent’s exchange with Eve in this account. Genesis Rabbah 19.5, for example, posits the administration of cold logic and tears by Eve, which while clearly offensive in this day and age would still be better than this bland reading.

[Right: The Fall of Man by Hugo van der Goes]

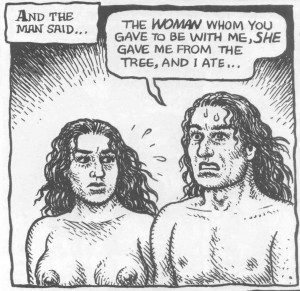

Eve’s look of consternation at Adam’s betrayal and shifting of blame (he is actually indirectly blaming God) in Genesis 3:12 is better for it shows at least some artistic involvement with the terse text.

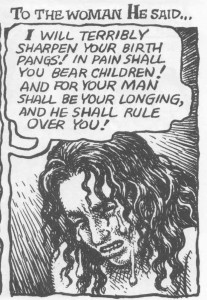

The entirety of God’s judgments from Genesis 3:14 to 19 are depicted without comment or analysis. The artist’s hand here is as distant as a machine-operated drafting tool. In response to Genesis 3:15 (“And I will put enmity between thee and the woman, and between thy seed and her seed; it shall bruise thy head, and thou shalt bruise his heel.”) we get a somewhat cursorily drawn snake wriggling away. It is common knowledge that Christians look upon these verses as the protoevangelium (for example, some church fathers saw the “woman” here as the virgin Mary and the “seed” as representing the church and/or Christ in particular) while Jewish commentators sometimes view the “seed” as a metaphor for humankind.There is little evidence of a response to these or any other interpretations here.

All this can be easily explained by constraints of time, space and artistic lassitude, but it should also be noted that Crumb (a self-proclaimed Gnostic) has little interest in Genesis as a religious or sacred text, a tremendous hindrance in adapting a book which has been largely interpreted in that context. As he clearly states in his interview at USA Today:

“To take this as a sacred text, or the word of God or something to live by, is kind of crazy. So much of it makes no sense. To think of all the fighting and killing that’s gone on over this book, it just became to me a colossal absurdity. That’s probably the most profound moment I’ve had — the absurdity of it all.”

Nor is there any suggestion that he took it upon himself to find out why the book in question has remained coherent and relevant to a multitude of very rational artists, philosophers and scientists through the ages. One hardly needs to believe to read closely and with an intent to understand. Thus stripped of emotional and mental investment, Crumb’s Genesis frequently degenerates into half-digested pabulum.

As would be expected, these issues have generated a modest amount of discussion online. David Hajdu writing in The New York Times adopts a more religious approach in his disagreements with Crumb and The Book of Genesis:

“For all its narrative potency and raw beauty, Crumb’s Book of Genesis is missing something that just does not interest its illustrator: a sense of the sacred. What Genesis demonstrates in dramatic terms are beliefs in an orderly universe and the godlike nature of man. Crumb, a fearless anarchist and proud cynic, clearly believes in other things, and to hold those beliefs — they are kinds of beliefs, too — is his prerogative. Crumb, brilliantly, shows us the man in God, but not the God in man.”

Points with which Dan Nadel of Comics Comics disagrees:

“I can’t see how, as an irreligious reader, you come away with that interpretation. I mean, there are two conflicting accounts of creation. Not exactly orderly. Also, Crumb is not, as far as I know, an anarchist, but he is, by his own account, spiritual. Which is to say, Crumb seems to be exploring the sacred. Maybe not Hajdu’s sacred, but sacred nonetheless.”

Hajdu wants Crumb to add a spiritual dimension to his reading of Genesis, something which is clearly irrelevant in the context of creating a fine adaptation based on modern day archaeology or biblical scholarship. Nadel seems more offended by Hajdu’s suggestion that Crumb lacks a certain spirituality which is equally of no consequence to this project, since Crumb is far more interested in the historical and mythological aspects of Genesis (i.e. not a journey of the soul but one of personal discovery).

***

It should be understood that while in-depth exegesis of the sort discussed above is frequently beyond the means of the single image (in painting for instance), it is certainly not unimaginable in the context of comics.

Failing to see this, Alter complains that “the foreclosure of ambiguity or of multiple meanings is intrinsic to the graphic narrative medium, and hence is pervasive in the illustrated text…The image concretizes, and thereby constrains, our imagination.” Then referring to the example of Genesis 9:20-27 where Ham sees “the nakedness of his father” he states:

“The most innocent reading, which is the one that Crumb chooses to follow, is that Ham simply saw his father exposed, thus violating what those who adopt this view assume was a grave taboo in Israelite society. This reading may well be right, though the report that when Noah wakes from his wine “he knew what his youngest son had done to him” might suggest that an act more palpable than mere seeing was perpetrated. Some interpreters in late antiquity, encouraged by these words and probably thinking of the Zeus-Chronos myth, imagined that Ham castrated his father, though this notion has always seemed to me rather unlikely. My own preference as a reader is to relish the shimmer of murky possibilities, including the more lurid ones, even if I am left without a concrete or confident picture of what actually happened. Pictorial representation forces you to decide one way–which, however appealing or plausible that way may be, imposes a limit on the story told in words.”

What Alter fails to realize is that the presentation of a host of concomitant possibilities is not beyond the reach of a comics adaptation. This is true even if pictorial representation will never possess the elusiveness, comparatively speaking, of spare sentences on a page. If there is a weakness here, it lies with the choices and abilities of the artist not the medium.

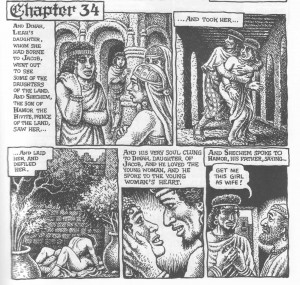

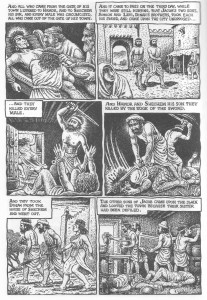

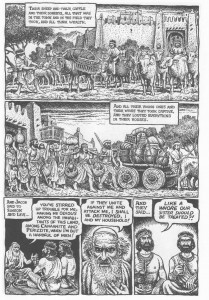

It may be that a trace of this hoped for ambiguity can be found in one of Crumb’s more successful passages in The Book of Genesis, one which Alter bring ups for special mention in his review. Genesis chapter 34 tells the story of Dinah (the daughter of Leah), her defilement by Shechem (the son of a Hivite Prince), and the terrible vengeance wrought on his people by the sons of Jacob.

The story is rich in possibilities: the ethical questions are right at the forefront, the underlying textural discourse plentiful.

There is the question of the narrator’s attitude (for, against or ambivalent) towards the events, the episode here being a mere prelude to a host of base acts perpetrated by Jacob’s sons until they encounter Joseph in Egypt. There is a cohesion which is implied in this arc that suggests a descent into moral degeneracy before a final redemption in the land of the Pharaohs. We also have the views of some early Jewish interpreters who saw divine sanction in the acts of Simeon and Levi (the prime movers in the slaughter of Shechem’s people). The Book of Jubilees, for instance, states that “judgment is ordained in heaven against them that they should destroy with the sword all the men of the Shechemites because they had wrought shame in Israel.” We also learn by way of Jubilees that Dinah was a girl of 12, a “fact” which has been used to justify the vengeful extermination of the Shechemites and to rehabilitate the victim, Dinah (by Luther; she had been used by early Christian interpreters as an example of idle curiosity and lust).

Lyn M. Bechtel’s suggestion that Dinah was not raped is alluded to but not confirmed in Crumb’s comic. Her tears in the penultimate page of The Book of Genesis have been taken for those of sorrow though it is not so hard to imagine them as tears of relief. In Crumb’s rendition of Genesis 34:3 (“And his very soul clung to Dinah, daughter of Jacob, and he loved the young woman, and he spoke to the young woman’s heart.”), an enraptured Shechem looks down on a woman who is caught somewhere between ardor and hopelessness (most reviewers have chosen to see the former). The greatest delights to be found in this section of The Book of Genesis may lie in this subtle play of facial and bodily expression.

This has some connection to a short comment by Tim Hodler (at Comics Comics) who takes a different tack in his response to Alter’s criticism stating that:

“Alter doesn’t then go on to recognize that the choices Crumb makes enable an entirely new set of ambiguities and artistic effects that aren’t present in the original text, and make the book worth evaluating as its own entity, and not strictly as a one-to-one translation.”

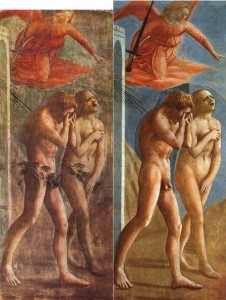

It must be said, that this an argument which I find of somewhat limited use in relation to The Book of Genesis, for the comic largely conforms to the circumscribed borders of traditional illustration impugned by Alter. To be more precise, the “effects” Crumb presents his readers with are considerably poorer than those suggested by the text and subsequently developed upon by scholarship. A number of reviewers have strayed on the side of leniency in considering these issues, not once remarking on the mere utility of Crumb’s choices. Alter who is sometimes cited as being unduly critical towards the end of his essay was in fact being inordinately kind. He censures Crumb for the “hackneyed” depiction of “God as an old man with a white beard” but then compares his drawing of the expulsion of Adam and Eve to Masaccio’s fresco in The Brancacci Chapel in Florence without comment.

___

___

[Right: The Expulsion from the Garden of Eden by Masaccio]

Even those possessed of untutored eyes should be able to see the difference in ability and insight at work here. Masaccio’s Expulsion may be deficient in textural fidelity but its spiritual immersion cannot be disputed. The rigidity of Crumb’s chosen style in The Book of Genesis makes it difficult (he does succeed occasionally) for him to adequately convey anguish, pain or psychological depth in isolation from the text.

I suspect much of this critical kindness is due to a barely realized condescension towards both form and artist. Thus we find the following account in Alter’s review:

“When some chapters of the book were published in The New Yorker in June, a few people with whom I have spoken about them expressed disappointment. Just the same old R. Crumb, they objected: he has not succeeded in developing a visual style that is adequate to the power of the biblical text. Such criticism does not seem to me justified. Crumb has always been an artist with a single style, a distinctive and emphatic one–in this regard as in others he is certainly no Picasso; and so it should neither surprise nor disappoint us that he has used his style to interpret the Bible.”

It is clear from these lines that Alter’s conception of the possibilities of comics and one of its greatest cartoonists is very low indeed. It is impossible to be disappointed if we expect so little.

In fact, in terms of sheer technique, there is nothing in Crumb’s earlier adaptations which can compare with The Book of Genesis. The amount of detail and rendering lavished on each page dwarfs virtually any other in Kafka for Beginners for example. Yet compared to some of this earlier work (such as “The Religious Experience of Philip K. Dick” or his excerpt from Boswell’s London Journal 1762-1763), it suffers from a certain stifling of the imagination. The Boswell adaptation proved a success for two important reason. Firstly, its length (the comic is only five pages long and the simple but fascinating artistic counterpoint at work would have become tedious at a greater stretch) and, secondly, the perfect alignment of subject and adapter.

As with his adaptation of Genesis, Crumb tailored his presentation to fit the elegant but ribald narration; the scenes are proffered at a discrete distance and only periodically punctuated with close-ups of Boswell’s excesses. This is in stark contrast to the paranoia and claustrophobia of the Philip K. Dick adaptation which is marked by subjective phenomena, mystical emanations and frank representations of insanity. Neither of these adaptation bring a substantial amount of analysis to the text but create frisson by way of ironic juxtapositions and personal proclivities. These comics suggest that Crumb’s gifts do not lie in deep inquiry or inquisition but in his idiosyncratic approach; his talent for revealing the extremes of human behavior. Jeet Heer identifies another engaging aspect of Crumb’s art when he writes that:

“…Genesis is a book about bodies, a book where men and women constantly grapple with one another, where a servant swears an oath by putting his hand under his master’s thigh, where even angels are threatened with sexual violation. Crumb has long been the preeminent cartoonist of the body. His women are notoriously full-figured, with ample butts and protruding nipples (a motif he uses in this book). But more significantly, the bodies he draws—whether they are quivering or standing still, dancing or drooping—have a visceral impact few artists can match. That’s why he was the perfect cartoonist to illustrate the Book of Genesis…”

A survey of the reviews online would suggest that it is these elements which critics have derived the most pleasure from as far as The Book of Genesis is concerned. I would suggest, however, that this is mean recompense for a full engagement with the intellectual treasures of Genesis. This explains why any suggestion (made in all seriousness in the comments of a recent review) that Alter would feel threatened (the words used are “nervousness” and “professional jealousy”) by Crumb’s awful biblical scholarship is laughable if not symptomatic of a deranged comics provincialism.

As Robert Stanley Martin indicates in his disappreciation of The Book of Genesis, this project (Crumb’s largest to date) cannot be accounted a success even if viewed purely as an act of storytelling. In fact, it conspicuously reveals the artist’s limitations as far as long form works are concerned:

“The overwhelming problem with Genesis is that Crumb doesn’t seem to have thought it through as a dramatic piece. The scenes are not played off each other for dramatic effect, and he doesn’t imagine the characters as distinct, idiosyncratic personalities whose interactions are greater than the sum of the parts…The refusal to see the project as a challenge in terms of orchestrating dramatic choices led him to repetitiously wallow in hackneyed treatments of the material, with most of the clichés of his own making.”

Crumb can be seen as a master of bizarre and transgressive imagery; a self-lacerating maniacal comedian; or a lewd, boisterous and cynical poet of modern living but his personality and disposition have lent themselves poorly to this undertaking. The individuals who are likely take the most satisfaction from this book will be those with a prior interest in comics. It is, after all, a work by a cartoonist of immense stature in the field. If this book does stand the test of time, it will be largely on that basis. For those with a serious interest in the original text and the rich tradition of biblical illustration, on the other hand, Crumb’s comic can only be seen as a well crafted curiosity.

__________

__

Update by Noah: This has started an ongoing series of posts on Crumb’s Genesis. You can see them all here.

I still haven’t read R. Crumb’s Genesis…and may well not after reading your essay. But I do wonder…why did he decide to illustrate Genesis in the first place? He doesn’t seem especially interested in the text, and it’s obviously a huge undertaking. Was it a dare or something?

Besides the instinctual/intellectual point you make as a weakness, I think Crumb’s visual resources are ill-suited for a text this long and complex. He’s not somebody who makes much use of ambitious layouts (at least not in this context), and he doesn’t push himself to vary his style much at all. That’s okay for shorter pieces…but in a long text with a fair amount of repetition, his palette seems really limited. The multiple close-up images of God you show above — arranged like that, it ends up being almost a self-parody (of Crumb, not of God.)

I had no idea he illustrated a PKD sequence. I’d love to see that. The Boswell is pretty interesting; as you say, it does seem a better fit for Crumb’s talents and interests.

Hey, Noah. I’m know you’ve read Jeet’s and Robert Alter’s reviews of Genesis. You didn’t get the impression that you should be reading Genesis from those reviews?

The inside flaps of The Book of Genesis indicate that Crumb was initially going to do a comic on Adam and Eve before being moved by the “Bible’s language, a text so great and so strange that it lends itself readily to graphic depictions.” Illustrating a book of this size and stature is a huge artistic gesture and many see it as a career defining comic.

Some of his interview statements seem to indicate that this was his first intense reading of Genesis. If someone told me that this was the first time he had read Genesis from beginning to end, I would believe that person. This is very much a beginner’s guide to Genesis, clearly of greatest use to those with secular leanings and a minimal knowledge of the text (though Derik Badman would disagree).

Interesting point about his skill with “layouts” and his “visual resources”. He’s certainly no arch formalist and it would be difficult to see him doing something like Karasik and Mazzucchelli’s adaptation of City of Glass. But the people who like Genesis enjoy this filtering of the text through a presentation which, in many ways, is quintessentially Crumb – the large women, the intertwining of these very Crumb-ian figures, the concentrated focus on human interaction, the familiar cartooning style etc. This is the essence of its attraction.

Can you clarify your comment on the element of self-parody in those multiple close-up images? The PKD comic is at the link in the essay.

I don’t know that I’ve read Jeet’s full essay — but I tend to disagree with him on everything (and vice versa!) so his endorsements don’t usually lead me to make medium-scale purchases. The Alter was a great review — but didn’t leave me feeling that the comic was worth looking at.

Re the self parody: basically, Crumb just seems to have a very limited range of ideas about how to show God being all commanding. You see a close up of God looking peeved once and maybe it’s impressive — over and over again and it starts to seem a little lame, and finally ridiculous.

I’d agree that the familiarity and lots and lots of Crumb’s signature style seems to be the point. It’s kind of depressing to me that such a seemingly ambitious work basically reduces to a large scale exercise in delivering more of Brand X to the eager purchasers of same — but that’s the way it goes, I guess.

If you want to see the Genesis as it should be done, go here:

http://tinyurl.com/2wdlnlz

That’s just giving me an error message, Domingos…is anybody else able to click through?

Here’s Dore’s Bible illustrations.

Noah:

This is getting ridiculous, please delete the other two posts. Search for “Aetatibus Mundi Imagines” in the search engine and click on the thumbnail:

http://tinyurl.com/35bkasl

Domingos is right. Those are some beautiful images. Easier access to a small selection of them at the Bibliodyssey blog site and also at Domingos’ own site.

Thanks for the thoughtful review.

My own reaction to the book, briefly, was that I was moved by Crumb’s depiction of human emotion. His “actors” display a range of subtle expression that I found very compelling, and at times, powerful. So I see Crumb’s approach as a sort of theatrical one, humanizing the characters in a very empathetic way. The choice to make God look like a human was a natural one, given this approach. It is, of course, interesting to consider what Crumb could have done, but I am deeply impressed what he did do.

See also here (I particularly like the vanitas; this theme would be huge during the 17th century):

http://tinyurl.com/2vcoojz

I thought the main thing that was impressive about this adaptation was how long it was… and that you can’t really look for the same level of attention to detail in a 600 page book as you would in a short story.

(Crumb’s book is only 225 pages, but considering how dense it is, and that most graphic novels are between 100 and 150 pages, it’s the equivalent of a 600 page book – also, it FEELS like a 600 page book, lol.)

I find it hard to believe that someone would spend more than four years of their twilight creative years on a project they believed, from the very beginning, to be derived from something they believed to be a “colossal absurdity.”

And I can’t believe it would have taken Crumb more than four years to have some type of epiphany about the source material, either. He’d have to be as dumb as a box of rocks for it to take that long — and Crumb is anything but dumb.

So… did he do an adaptation of Genesis for the money? The notoriety? The challenge? The professional development? All of the above?

Or could it be that as Crumb knowingly gets closer and closer to the day when he’ll be truckin’ on off to the big drawing board in the sky, he’s consciously or subconsciously wrestling at some level with questions that are metaphysical, personal and profound.

I don’t know, Russ. Crumb’s a pretty weird guy. In some artists, there’s a compulsive, fetishistic quality to their creativity which seems linked to a idiosyncratic vision — you think of Henry Darger, or Blake, or Bosch or any number of other folks. Crumb has the compulsive, fetishistic creativity — but it doesn’t seem linked to anything in particular. In terms of his “vision,” he’s a garden-variety liberal cynic, as far as I can tell.

Which is to say — I can see him undertaking an enormous project without really believing in it or caring about it in some sense, because “belief” as such has never really seemed connected to his art where you’d think it would be.

David: Yes, I understand what you’re saying here and it does appear that people who enjoyed the comic found a lot to like about the “theatricality” of the adaptation. It’s somewhat similar to what Crumb does with the Boswell journal and much of his earlier work. The problems really occur when people start to look for more than Genesis as filtered through the usual Crumb shtick – there’s very little beyond that. And that’s my problem as well since I wasn’t moved at all by anything in this comic adaptation.

Subdee: Your point is well taken but it merely points to a well known hindrance to the creation of a good comic – the labor intensiveness of such ventures. It’s a factor which really can’t be taken into account in the assessment of the overall quality of the work under review.

Russ: As mentioned above, it would appear that Crumb’s initial attraction was to the language of Genesis. I assume he must have discovered the “colossal absurdity” of the work right at the start from his initial reading. The question is why he persisted with the work of adaptation. There is very little “notoriety” to be gained from adapting Genesis the way he did – it’s as bland as can be and calculated as such. The “challenge” of taking on such a work must have been a factor, as well as his interest in matters Jewish. Further, Crumb has never displayed any gifts at creating long form works from scratch. I assume he needed a writer or a text to base his drawings on, and Genesis might have appeared to be an ideal capstone to a long career.

This is all idle speculation of course. On the other hand, there’s nothing in his statements on the book so far to suggest that he found Genesis helpful in his spiritual growth (at least, none that I have read). And, yes, everything which Noah says applies as well – the spur to creativity is sometime inexplicable.

You ask whether it could have been about the money. There’s always that factor to figure in and I don’t think it should be held against him if this way a primary motivation. If you’re drawing 200+ pages of comics (esp. one derived from something you find dramatic but absurd), you need to have something to keep your eyes on. Simple drawings by Crumb already command prices of a few thousand dollars and there have been rumors that the entire book will be sold for a six figure sum (I should stress that this is only hearsay). I sincerely doubt if he actually needs the money since he could easily sell a sketchbook now and then and lead a pretty comfortable life.

NB:But I do wonder…why did he decide to illustrate Genesis in the first place? He doesn’t seem especially interested in the text, and it’s obviously a huge undertaking. Was it a dare or something?

This interview might answer that question for you.

Though he has admitted he believes God exists at least a few times in the past decade. There’s a panel from one latter day cartoon(one of his jams with Aline?) where he admitted a growing interest in God the older he was getting.

No, that interview isn’t especially helpful. He was kind of interested in the myths behind it; he was offered a lot of money…I mean, those are answers, but they seem inadequate given the time and effort required.

In some sense with all art the ends justify the means. If you think the book works, then the effort invested seems worthwhile and therefore rationale. If, like Suat, you feel the result is lacking…you end up wondering what on earth the man was thinking when he decided to put the thing together.

Noah wrote: “Crumb’s a pretty weird guy. In some artists, there’s a compulsive, fetishistic quality to their creativity which seems linked to a idiosyncratic vision — you think of Henry Darger, or Blake, or Bosch or any number of other folks.”

Yeah, he may be obsessive to some degree, but four years is an eternity to a sexagenarian, and while I’m no Crumb completist, I don’t recall any past instances where he devoted so much time and energy into a project which, as he insists, he thinks is the height of absurdity. Near as I can tell, this project is a Crumb anomaly on a number of levels.

I really liked the human aspect. Putting flesh and real emotion on the figures of Jacob and Esau, of Joseph…Abraham’s near-sacrifice of Isaac was so intense in his depiction;

You know, he might also have been attracted by the fact that Genesis is also a terrific yarn, or collection of yarns!

And yes, he could have been more thoughtful and subtle in his exegesis.But who’s expecting a Talmudic level of interpretation?

finally, could the book not embody a critique of Genesis and of monotheism?

I can’t help think you’re making a mountain out of a mole hill. Based on the book’s introduction and the conversation I attended between Crumb and Mouly, my understanding is that Crumb started out to do a vicious satire of the Adam and Eve narrative in Genesis 3. In fact, he got a few pages of that story done. But the more he wrestled with the text, the more impressed he was with it. This led him to take a serious look at the entire book of Genesis. He was amazed at what he found and decided to illustrate the text in hopes of making it more accessible to other people. He may have found it crazy, but it also found it compelling. He wanted others to read and wrestle with this book too.

You seem to be committing the same error as those you critique at the beginning of the essay. You are examining this illustrated version of Genesis with a fine tooth comb because Crumb’s name is attached to it. He is not a Biblical scholar, so why expect him to be offering commentary and interruption in his illustrations. In fact, given he isn’t a Biblical scholar, do you really want him to? I’m glad he isn’t trying to incorporate the latest postmodern, feminist theory of God in his illustrations. Or that he trying to give a Freudian representation of the Tree of Life. I like that this is a naïve reading and rendering of the text.

The world of Genesis is strange to most modern readers. Crumb is making the world of the patriarchs tangible. By giving us some visual idea of what life was like for Noah, Abraham, Joseph, etc. , he is making their stories more approachable. I applaud him for that.

I think expecting this to be a visual summation of modern scholastic debate on the book of Genesis is beyond the pale. It’s meant to be a picture book for adults and that should be the focus of our criticisms.

Hey Ed. Nice to see you back here again.

Suat is responding to critics who have suggested that the book has something of value to add to the interpretation or representation of Genesis. He’s also responding to the sense among many that this is Crumb’s crowning achievement, and therefore a major work of art.

Your response is similar to Alter’s — that is, Crumb is just going to be Crumb; it’s silly to expect more of him. As Suat said, that’s fairly condescending. Crumb is probably the single most respected cartoonist in the Western world at the moment. If comics is indeed a mature, genuine art form, and this is indeed the capstone of Crumb’s career, then why shouldn’t we expect him to produce something on a par with Michelangelo, Blake, Dore, Masaccio, or the amazing work Domingos links to above?

Suat doesn’t say the work is horrible. He says that, in comparison to similar projects by many other artists, it’s simplistic and unambitious. You respond by saying that the work is simplistic and unambitious. The only disagreement is as to whether or not it’s fair to hold Crumb to a higher standard.

Noah,

If Crumb were doing an illustrated history of the underground comic movement, then yes, I would expect this to be a significant, multi-layered work. But since this is a layperson just expressing enthusiasm, then I’m not expecting much. Particularly, when he has stated his modest goals for the work.

I don’t think that everything Crumb does has to be a ground-breaking work. He should be allowed to do simplistic projects too. I’d hate to think that Crumb has been so legendary in mind of comic critics that he is no longer permitted to just be an average Joe making pictures for fun. That’s a terrible burden to place on any artist. Even Picasso took time out to draw a few kids’ pictures.

I do think we should take artist intent into consideration when determining how to critique a work. I would find it equally unfair to critique Dr. Suess for not incorporating modern theories of child rearing and language structure in Horton Hears a Who!

Ed, is your response also to Jeet, then, who made the assertion that Crumb not only should be expected to do ground-breaking work, but actually had?

Artist’s intent is largely irrelevant in determining how a work fits into a larger tradition, which is what Suat was trying to do. If your point of reference is Classics Illustrated, this looks a little like Biblical exegesis, but if your point of reference is Blake, this looks like Classics Illustrated.

But since the subject was intent: it’s important to note that Picasso had no interest in being an average Joe: “My mother said to me, ‘If you are a soldier, you will become a general. If you are a monk, you will become the Pope.’ Instead, I was a painter, and became Picasso.”

Alex: I’ve seen a number of these biblical figures depicted as fleshy individuals with “real [emotions]” since I was a kid, so a largely uninvolved transcription doesn’t really do it for me. Crumb’s illustrations are far from insipid but by choosing straight illustration, he invites all sorts of unwelcome comparisons. Like the scene you bring up with Abraham sacrificing Isaac; yes, it’s competently done with some useful skill applied to the drawings of Abraham but I can’t look at that scene without remembering the famous paintings by Caravaggio and Rembrandt. This is especially true if you compare their depictions of Isaac in that episode.

I think there’s little doubt that Crumb approached Genesis as a series of interesting stories. However, the ad hoc approach to the retelling does the text a disservice; there’s very little effort made to suggest any unity in the account. This is the way I read Genesis as a child. The adaptation can be seen as a critique of Genesis but one with very little meat on it. He probably felt that the text (and its inherent absurdities) would speak for itself.

No one’s looking for deep exegesis here, just some evidence that he did more than just react superficially to the text. There seems little point in retreading ground your artistic betters have fully exploited half a millennium ago.

Ed: Thanks for your comments. Noah and Caro have answered on my behalf and very well at that, so I won’t be adding much more.

Some of your points are answered in my reply to Alex. I want to stress (if it isn’t already clear) that I’m approaching the adaptation from the perspective of a layman not a scholar. All my points above proceed from that viewpoint. Alter, on the other hand, is a much respected biblical scholar. The difference of opinion lies in the fact that I treat comics with the same consideration and respect I do art, literature, music or film. I don’t consider it a lesser art form.

I do understand your point that The Book of Genesis was not meant to be much more elevated than a simple picture book or Crumb’s doodlings on napkin art. I don’t for a moment think this is the case; it seems like a pretty large artistic statement on which he worked for 4 years of his life. But your opinions do make sense if that is your viewpoint.

Caro,

Yes, I would respond to Jeet the same way. Again, even Picasso acknowledged not every painting he did was ground breaking. He was careful to point out when he was just playing around.

I understand trying to put a work in content. However, if Crumb simply wants this book to be Illustrated Classics for adults, it’s unfair to compare him to Blake. We can certainly talk about how Crumb inherited his images of the God from a tradition influenced by Blake. But it’s unfair to Crumb and the book to say that he fails to live up to the standards of Blake, when he never sought such a lofty goal to begin with. If your goal is to jump off the 3′ high diving board, then it’s not fair for onlookers to chastise you for not jumping off the 20′ high diving board.

Ng Suat,

We can disagree about Crumb’s intentions for the work. I interpret his statements to say, he did not intend this to be a major artist work. I don’t see the number of years he worked on the book as material to whether it’s a major artist statement or not. If he decided to spend four years making a picture book, then so be it. We might think that’s a waste of time and talent, but that’s Crumb decision to make.

Ed, I don’t think Crumb ever says that he’s a great artist, does he? He always downplays his own work, I think (I could be wrong…but for instance he seems to consistently denigrate the Breughal comparison whenever it comes up.)

Noah,

That maybe be true. I’ll have to go back and look at some interviews to be sure. If so, that’s a great a rebuttal. Thanks for pointing that out.

Hi Ed, I presume you mean psychologically unfair as opposed to “artistically unfair” (or critically inappropriate), when you say this?

It’s always critically appropriate to compare and contrast two (or more) works with the same subject matter, which is why I presume the former.

But I can’t imagine why it would be a critic’s responsibility to worry at all about Crumb’s psychology. He’s a grown man and a public figure; I think he can take Suat saying, “Really, people, this doesn’t compare to Blake. Stop with the hagiography already.” It’s not like Suat calls him egregious or anything.

We’ll be talking about Crumb long after he’s dead, and at that point his feelings will really be irrelevant, so if we let that get in the way now it basically means that a first-rate critical analysis of the man’s work can’t begin while he’s alive. That seems absurdly limiting for no benefit.

Caro,

I actually mean artistically/critically unfair.

It’s okay to compare any two works of the same subject matter, if you acknowledge the different intentions and audiences for the two works. I would object to comparing Disney’s Hunchback of Notre Dame and the 1923 Hunchback of Notre Dame as if they were artistic equals.

I think it might be more apt to compare Crumb’s Genesis with Kubert’s instead of Blake.

Hi Ed: Why is it so important that intentions be acknowledged?

I accept the audience issue for the Disney movie, because it’s age-based, but I’m not sure why the audience for Crumb’s work is inherently different from the audience for Blake’s. Both are books for adults with the same subject matter. A critic like Suat is surely part of the audience for both.

Unless you are claiming that the “audience” is automatically defined as “people who think it’s brilliant.” That seems tautological, since by that measure no creative effort could ever be evaluated as anything other than perfect.

I should say that I don’t think the audience issue even in the Disney film precludes comparison: the difference is that it is a comparison of a derivative work with its original source. The POINT of that work is adapting for a different audience.

Crumb’s work is not an adaptation of Blake’s work; both are adaptations of another original source, so they are, in fact, equivalents. The parallel situation to the Disney film would be if we were actually comparing Crumb’s work to the original, Biblical Genesis — his source material.

For those wanting to check out what Ed is talking about, here’s a link to a blog which discusses the comic in question (drawn by Joe Kubert and Nestor Redondo). It’s a counterpart to all those biblical adaptations mentioned in Charles Hatfield’s post. I haven’t seen images from that comic in years but it does appear to be setting the bar very low.

Also, I obviously agree with what Caro is saying in her comments.

Yeah; I don’t really see why or how setting rules on what works can and can’t be compared is in any way useful. It just seems really condescending. Crumb is a major, important artist, whether he wants to be or not (and I’m sure he doesn’t mind at least re his bank account.) When you’re a major, important artist, people expect your work to measure up to work by other major, important artists. That’s a reasonable and respectful criteria in a critic.

Furthermore, illustrating Genesis is *in itself* a major artistic throwdown. The Bible is the Bible; it’s a major cultural document, and illustrating it automatically holds you to hight standards. I’ve done Biblical illustration myself (for the Flaming fire illustrated bible project.) I wouldn’t make any great claims for my interpretive efforts or my genius. But I think it would totally be fair game for someone to come in and hold my work up to the best that has come before and find it shockingly wanting. In fact, I’d be hugely flattered if someone did that. It’s a compliment to be spoken of in the same breath with the best in the world. I’m not a huge fan of any of Crumb’s work, but given his status, his position, and his reputation, I think you’re being unfair to him in suggesting that he doesn’t merit that consideration.

Caro,

Because artist intention lets us know who the artist saw himself competing against. What standards did the artist set for the work. We should judge the artist based on what they were trying to accomplish, not what we wished they had accomplished.

For example, is a novelist trying to be the next Dan Brown or the next Iris Murdoch? If we compare a guy trying to write a potboiler to Murdoch, then he will fail completely. We will have harsh condemnations of his work that aren’t critically justified because he’s not writing to that level. If we compare the potboiler to Brown, we might find he did a great job. Heck, we might find he did better than he intended.

How would you suggest we set limits on what artistic works we compare against each other? Should every comic be compared to Maus? Should every painting be compared to the Mona Lisa?

Would you compare Kubert’s Biblical comics to Blake? Why or why not?

I’d be happy to compare Kubert’s comics to Blake, sure. I’d compare a painting to the Mona Lisa if there was a reason to (folks talked about Frazetta’s work in comparison to Da Vinci’s in a recent thread here, for that matter). And I’d compare any number of books favorably to Maus, which I think is a solidly mediocre comic which needs to be scoffed at much more than it is.

I think if a critic has a good reason to make a comparison, there’s no reason not to go ahead. A “good reason” here definitely includes two illustrators illustrating the same thing.

Critics and readers really shouldn’t be bound by artist’s intentions, as Caro says. It’s not up to an artist to set rules as to what people can and can’t say about his or her work. That way lies boring conversations and probably worse art.

Noah,

My problem with what your argument is that you trap an artist into the criticial perception of him/her. So Updike can’t write a silly kids’ book? “I’m sorry Mr. Updike, the critcial community has judged your talent and reputation too great to pursue projects of such low stature. Please go write something brooding and reflective.”

If Crumb wants to spend the rest of his life being the artist for Tiny Titans, why can’t he? If he does illustrate an issue of Tiny Titans does that mean we have to judge that issue of Tiny Titans against the children’s illustrations of Edmund DeLuc?

What right do critics have to pose such limitations?

My apologies to Ng Suat Tong, I’ve driven the conversation far off topic. Your essay deserves better respect. Please forgive me. I’d like to get back to talking about your analysis of Crumb’s work.

Even by saying two things aren’t on the same level (and thus, by Ed’s standards shouldn’t be critically compared)… isn’t that making a critical comparison?

It’s one of those invisible critical comparisons that isn’t often examined, but it’s there none-the-less.

Ed, I can’t imagine why you think we are judging the artist rather than the work itself.

Well, rather, that’s Noah’s point: we’re judging the artist as worthy of comparison with Blake. We’re judging the work as not quite measuring up.

But more to the point – yes, every comic should be compared to Maus (or the work of equivalent quality that is related in some way, although I think Maus is badly overrated) — AND every comic should also be compared to the Mona Lisa. That’s called having critical standards.

It won’t necessarily get you anywhere. If you compare a harlequin romance to Jane Austen, you’ll end up where you’re starting – the intentions are so different that this comparison goes nowhere.

But that’s not ALWAYS the case. Sometimes an artist creates something that is greater than his or her intentions, and only through comparison can that be recognized. Sometimes there are peripheral elements of a work that resonate with significant works even though the overall work doesn’t compare well. The reason Noah is saying your position is condescending is that it presumes that situation will not happen, that no artist can ever surpass his or her expectations.

It makes sense to compare a work to a work that has something similar – Iris Murdoch didn’t write potboilers, which is why your comparison sounds so absurd. But sometimes similarities are elusive or partial: you could compare the morality of Brown to the morality of Murdoch; you could compare a potboiler about sexual relationships and the unconscious could to Murdoch’s treatment of the same. (And if the critic is Noah, the potboiler would probably win.)

Basically, the only work that isn’t worth comparing to ANY other related work is a work that the critic just considers too trashy to bother with. Is that what you’re really trying to say about Crumb?

I should maybe add — I think there’s lots in Suat’s essay to talk about, but I don’t think yours is a detour or an unfair line of discussion at all, Ed. On the contrary, I think it’s central to Suat’s essay, and to comics criticism in general in a lot of ways. So no need to apologize for bringing it up — at least not as far as I’m concerned! (Of course, you were apologizing to Suat in the first place, and perhaps he feels differently….)

No, I don’t feel differently. This is a line of inquiry which I haven’t seen in discussions about Crumb’s comic. So please carry on and don’t hold back on my account.

If I don’t respond to you now, it’s because I have to go to bed (only 6 hours before I go to work!).

Noah, Caro, & Ng Suat,

Give me some time to process this all and I will get back to you tonight. You all have been very kind and patience with me. Thanks.

What!? You’re going to take time to think?!

Damn it, man. Don’t you know this is the internet?

Comparing Crumb with Blake involves comparing Crumb to Blake. Both were/are strongly opposed to organised religion.

I still maintain that Crumb’s ‘Genesis’ is largely a critique of Genesis. And Suat,I believe you underestimate the earthy, sweaty, hairy beauty of Crumb’s “Genesians”.

Go back to Crumb’s illustration of the so-called ‘begats’, considered by just about everybody to be the most boring passages in the entire Bible. See how he humanises them with vignettes of each man’s life. And what poignancy attends the simple repeated formula: ‘Then he died.’

Suat, perhaps you are a Christian believer? I’m not trying to go all ‘ad hominem’ on you, but it seems the severity of your judgment is linked to your estimation of the spirituality of the book.

And I disagree with you about the Abraham/Isaac scene. As it is played out in Crumb’s visual narration, the suspense engenders feelings of pity and horror. And the reader legitimately wonders at a God who’d impose such a test.

Silly Noah. We like thinking.

Ed, glad we weren’t too rough on you – I think you took the brunt of my heightened sensitivity at the moment (post-Interview Discussion) to the Cult of the Author in Comics.

Looking forward to your return!

Derik, That’s a great point. I think we can agree that there are some works that show an obvious discrepancy in artist merit. I wold hope you never attempt to compare a stick figure drawing I did with the Mona Lisa. If you did, I think it’s proper for the Mona Lisa to break decorum and spit in your face. I would actually expect her to.

I can see what Ng Surat, Noah, and Caro are saying about comparing artist works with similar subject matter. However, I’m still uncomfortable with comparing Crumb’s Genesis to paintings and Blake. I believe there is too much disparity between these works.

I’m not convinced paintings and comics should be compare in general. A comic is trying to tell a sequential story through multiple images. One image is never meant to bear the whole message. A painting is trying to capture a moment. It’s trying to find the right moment to convey all the complexity of the story in a single image.

My problem with comparing Blake and Crumb is that Blake wasn’t interested in literal interpretation. He was intentionally trying to infuse his theology and interpretation of the text into his illustrations. He was seeking to convince the reader to accept his point of view of the narrative.

If we’re going to compare Crumb to previous efforts to illustrate the Bible, than I’m more comfortable with comparing Crumb to Gustave Dore, Albrecht Durer, Joe Kubert, and the like. (Not sure about Basil Wolverton) People who were trying to give a straight forward illustration of the Biblical text. People will goals similar to Crumb. This is why I think artist intent is important. I helps to ensure we compare the work to other works of not just similiar subject matter, but similar nature.

Ironically, Crumb is trying to be a good fundamentalist. He claims that a lay person will little to no theological knowledge can read the Genesis text and come away with a proper understanding of the narrative. That should be the exegetical statement that Crumb is critiqued on. That is the theological perspective embraced in his work.

Caro, I think that Noah is the one engaging in the cult of the artist. He is claiming that everything Crumb does is a significant artist statement simply by virtue that Crumb’s name is on it. I call shenanigans. If Crumb wants to spend his latter days writing crappy kids’ comics and illustrating them poorly then they are nothing more than badly written kids’s book with bad drawings. I don’t think that everything an artist does has to bear the weight of all the works prior to it. Each work should be judged on it’s own merits independent of artist talent and reputation. I also believe that an artist is free to turn his back on his talent and reputation and do what he/she wants.

Caro, I didn’t mean to imply that any critique of a work is a critique of the artist. I can pan a work and still think the artist is a wonderful human being or that they are a great artist. One bad day doesn’t destroy a reputation.

Now I do think artists can crash and burn. I would point to Ditko’s Chuck Norris comics as a tragic example of a great artist doing hack work.

Alex, I am a Christian (Eastern Orthodox). I love Crumb’s genealogy pages are brilliant. They are my favorite pages in the book. He really brought the text to life. They are worth the price of the book alone. I also love how earthy and real he makes his characters. These are not the well manicured patriarchs walking dustless dirt road of Cecil B DeMille.

I hope this address everyone’s questions and concerns.

Alex: I’m an admirer of Crumb’s art and The Book of Genesis if viewed as an act of pure cartooning will undoubtedly stand as his finest work as far as pure technical ability is concerned. It’s hard not repeat oneself when it comes to drawing as many figures as is required by this adaptation but there are periodic moments where Crumb’s command of facial expression is impressive. This applies to his scene setting as well, but he is often less inspired in critical moments like those in chapters 2 and 3 or even those depicting the flood. We can agree to disagree on that Abraham-Isaac scene you mention, but consider the Caravaggio for example. Don’t you find it much more disturbing to see, as one critic put it, a man willing to gut his son as he would a fish? What does this say about faith and fanaticism?

There’s no doubt that a reasonable amount of research went into the construction of chapter 11 of Genesis (the one with the “begats”) but Crumb’s notes also indicate a somewhat facile understanding of much of Genesis. Honestly, it’s not a particularly boring section if you read a commentary which explains its significance. There are parts of Numbers which I find considerably more dull than that passage but I’m sure these too are meaningful in ways I could not begin to understand without additional help. I’m not especially moved by what Crumb does with the material in Chapter 11. It’s imaginative and worthwhile but they’re still figures on a page to me. On the other hand, it may well be the best depiction of this chapter in comics history. I’m just not a very emotional reader when it comes to Genesis.

Are you saying that this is all there is to Crumb’s comic? A vivid reimagination of time’s past for those who find the original text dull and tedious?

You’ll need to expand on your point that “Crumb’s Genesis is largely a critique of Genesis”. That sentence seems little better than Jeet’s comment that the comic is “exegesis”. In what way and to what extent does the comic open up the text to contemplation or ridicule? Your earlier point concerning Monotheism (a tenet of the earliest patriarchs or a later development?) is especially important in the context of Genesis but is not really brought to the fore in this adaptation.

As to your other point, who knows what prejudices we bring to a reading of any work? I’m certainly a Christian but my readings of Genesis of late have focused almost exclusively on its intellectual qualities. I don’t see my judgment of the comic as particularly severe but if it is, I would say this is undoubtedly linked to my estimation of the book’s worth in that regard. Now much of Genesis can be read as a very flat “history” of the origins of the Jewish people but this robs it of much of its subtext and thus underlying power. Genesis has very little to do with history as we understand it today. As I’ve made clear in the article above, requiring spirituality from Crumb in relation to Genesis is an exercise in futility, but that’s only one option among many.

“He is claiming that everything Crumb does is a significant artist statement simply by virtue that Crumb’s name is on it. I call shenanigans. ”

Well, not exactly. I’m saying that anything Crumb does is fair game to be judged in comparison to work that is significant. That doesn’t really have anything to do with my own estimation of Crumb’s work, which isn’t especially high. But you can’t just step out of the culture and pretend that Crumb is just anybody. Tons of reviewers are talking about the significance of this work. If you write about Crumb, that’s the conversation you’re in. Pretending that you can approach a work without that cultural baggage seems like wishful thinking — and I’m not even sure why you’d want to wish it.

The distinction between illustration and art is interesting. I’d say there isn’t as absolute a wall there as you’re arguing, and that comparisons aren’t as difficult as you make them out to be. Even so, I find Dore’s work much more powerful than Crumb’s — though I’d need to read Crumb’s entire book before I could really make the case (if I didn’t change my mind.)

Noah,

Fair enough. I think there is a lot of room for debate on these issues. Thanks for the great discussion.

This is an excellent review, Suat. It’s a shame it can’t be included in the print TCJ’s forthcoming roundtable on the book. It would have a terrific addition.

My fellow roundtable participant Tim Hodler even liked it. Click here.

Well, maybe “like” is too strong a word. But Tim does respect it.

Ha! That made me smile; I’ll settle for respect. And thanks for the compliment.

Hi, Suat. I want to answer your review at some length because I have a lot of problems with it. I see numerous errors, a casual reading of the book, and some shaky assumptions supporting the whole thing. You make a number of dismissive remarks in the review and the comments that strike me as haughty, unfair, and wildly off-base. The biggest problem is that you’re falling readily into a basic error for a critic: refusing to assess a work on its own terms.

I should add immediately that I have an indirect entanglement with this (as they say.) You mention my suggestion “…made in all seriousness” in the comments to Heer’s post that Robert Alter, in his review for the New Republic, “would feel threatened (the words used are ‘nervousness’ and ‘professional jealousy’) by Crumb’s awful biblical scholarship,“ calling it ”laughable if not symptomatic of a deranged comics provincialism.“ It’s not right for me to get after you for saying things I find arrogant without apologizing for that. ”Professional jealousy“ was way too strong, and I take it back.

What I said was that Alter seemed nervous about the use of his translation- he spoke of his ”entanglement“ in the project, and the man’s job is choosing words- and may have nursed what I did call a professional jealousy between one exegete and another. I found Alter gracious and full of biblical insights, saw that he made a good effort to engage Crumb, but my reason for saying that was that he treated the adaptation as a failure because it couldn’t be regarded as definitive. I thought he was basically telling us why we should still read the Bible (preferably with his notes), and didn’t seem to grasp that Crumb was suggesting possible interpretations in much the same way he did, though his commentary did have the advantage of being able to list several at once. I‘d never say ”Crumb’s awful biblical scholarship“ was threatening to him, rather the rampant popularity that defenders of the canon ascribe to comics, and the notion that youngsters who read it might assume they’d read Genesis itself because the comic book has every word.

I am honestly not bothered by being called a ”deranged provincial“- feel free to look at me that way- and I hope it will be apparent that my issue is with other things you’ve said. According to you, Crumb did not ”read closely and with an intent to understand,“ his adaptation was ”stripped of emotional and mental investment,“ it suffered from ”artistic lassitude“, ”awful biblical scholarship,“ and an ”almost anti-intellectual approach“. You even pull ”half-digested pabulum“ out of the Comics Journal grab-bag. (Could it also be pernicious, odious, fatuous, and supererogatory?) ”Those with a serious interest in the original text and the rich tradition of biblical illustration“ can only find the book a ”well-crafted curiosity,“ and it ”might be of greatest use to readers whose minds are in a more formative state.“

This is strong stuff. I want to examine it by looking at the same parts you do and I’ll try to build into an overall assessment of your approach. I hope to also answer not just your review but a certain strain of commentary I’ve seen about the book.

The creation and fall of man are ”the two most famous chapters in Genesis… these factors will make the ascertainment of the extent of Crumb’s achievements in The Book of Genesis that much easier.“

This convenience is significant. My unscholarly sense is that visual adaptations of Genesis tend to fall back on the Garden of Eden and the Flood, with the second rank including the Tower of Babel (one famous image), Sodom and Gomorrah (fiery rain and pillar of salt), the sacrifice of Isaac, and Jacob’s ladder. Creations have been done but seem a bit vague for most artists; I think I should be able to call a famous Cain and Abel to mind, but can’t. Much of Genesis, as with the rest of the Old Testament or Hebrew Bible, is unfamiliar in visual art or dramatization, and parts may never have been depicted. (Anybody can scrape up examples with an image search, but let’s play fair; you know what I mean.) Jesus and Mary have been the stars of Western art, and the Hebrew Bible is recalled in a sprinkling of highlights.

A comprehensive visual dramatization of Genesis is unprecedented. This is a major part of this project’s reason for being. As Crumb says, “they gloss over it. When you’re a kid, they don’t inform you that Lot has sex with his daughters. Or that Judah slept with his daughter-in-law. Those parts are just glossed over. In illustrating everything and every word, everything is brought equally to the surface. The stories about incest have the same importance as the more famous stories of Noah and the Flood or the Tower of Babel or Adam and Eve or whatever. I think that’s the most significant thing about making a comic book out of Genesis. Everything is illuminated.”

There are other virtues to the adaptation, which will hopefully emerge in my examination and will be discussed as I wrap up. But the glaring obviousness of this one makes me wonder how seriously you’re taking this when you say things like ”there seems little point in retreading ground your artistic betters have fully exploited half a millennium ago.“

Your choice to focus on the Garden of Eden is itself interesting, since it’s highly atypical. It is the only part shorn of costume, tools, man-made structures, and any human culture at all. The characters are ideal ”types“. Visually, the rest of the book is astonishing in its quotidian detail, and one can find new delights on any page even after multiple readings, but the relentlessly straight-on layouts and total commitment to a credible milieu for the patriarchs create a rigorous visual style that could be considered as much a demand on the audience as classic art-house cinema. You can dismiss it as boring (for devil’s advocacy, here’s Johnny Ryan: http://www.viceland.com/int/v17n1/htdocs/ryan-comic-311.php), but there’s also a seriousness to it.

By contrast, the Garden of Eden scenes are playful and fanciful. You point out this lightness, comparing the moment when Adam and Eve cuddle next to God and the woodland creatures to Disney. And you’re not wrong. (Though this is right before a startling tonal and narrative shift when it to a different version of man’s creation, this one primal and stark, right on the same page- a bold feature that I’ve never seen in an adaptation.) But your handling suggests that the tone of these parts is consistent with the rest of the book. You even point to the Adam and Eve scenes to answer Ken Parille’s description of the book’s aesthetic, without any hint of their difference:

”Crumb’s illustrations assume a sort of perfection of human form and behavior as far as Adam and Eve are concerned. I presume that this is one example of the “beautiful” materiality of The Book of Genesis which Ken mentions in the excerpt above. There is certainly a degree of exaggeration and a filtering through the artist’s eye but this is not a particularly earthy version of Eden… There is very little of that grimy commonness which we see in the Gospel adaptations of Pasolini or Chester Brown.“

You write of Crumb’s drawing of the creation of Adam, “his solution was not an uncommon one during the Italian Renaissance, here made fresh by showing the stages in this act, in particular the breath of life given to Adam (the word “breathed” or “blew” here suggesting the intimacy of a kiss). Crumb’s adaptation is also notable for showing Adam in his clay-like state, a reminder of the Egyptian (see The Hymn of Khnum and Hekat) and Mesopotamian (see Enki & Ninmah, and Bel) myths which carry the same motif.

“As articulated in his short commentary found at the end of The Book of Genesis, Crumb is particularly interested in these ancient tales of creation and periodically inserts them while neglecting to emphasize the many internal consistencies, dilemmas and word plays in the Biblical narrative. Thus, for example, the “dirt of the ground” is linked to pagan tradition and not to a play on the words “man” (adam) and “ground” (adama) where “man is related to the ‘ground’ by his very constitution (Genesis 3:19), making him perfectly suited for the task of working the ‘ground,’ which is required for cultivation…his origins also become his destiny” (Kenneth A. Matthews).“

Where do you see a pagan tradition being inserted? The text specifies that God blows life’s breath into the man’s nostrils. Adam’s constitution from the ground is vividly illustrated. It could be reminiscent of Mesopotamian or Egyptian motifs but Crumb never mentions this in his notes, and the Bible does say “the Lord formed the man from the dirt of the ground.” It’s not clear what suggests to you that the artist is unaware of the link between man and ground or his destiny to work it, or what kind of signal you were hoping Crumb would send.

But you miss the way Crumb does emphasize Adam’s name and connection to the ground after these three panels. You’re not much impressed with the high-volume dressing down Crumb has God give Adam and Eve: “The entirety of God’s judgments from Genesis 3:14 to 19 are depicted without comment or analysis. The artist’s hand here is as distant as a machine-operated drafting tool.” But surely you noticed God’s jabbing finger. He does it a lot in that scene. The action through the Creation has been led by what God does with his hands- always with open palms, arranging things, introducing people to each other and their habitat. The only time until now that he pointed was to identify the forbidden tree. The only other pointing was Adam’s, naming the animals. Now God points at him: “To Adam he said… Cursed be the ground because of you!… By the sweat of your brow you shall eat bread, till you return to the ground, for from there you were taken! For DUST you are, and to DUST you shall return!” (Crumb’s emphasis.)

It’s easy to miss, but until now Adam has been “the man.” This is where he is named- named earth, or dust. Crumb has associated pointing with forbidding, punishment, and naming. For the expulsion from the Garden, God sends “him”- not “them“- “forth to till the ground from which he had been taken,” and Adam is shown carrying a tool. They’re in new, uncomfortable clothes, distressed, and getting ready for a life of work. On the next page we meet Cain, “a tiller of the soil”- who is constantly shown flushed and sweating. Crumb is recalling God’s line that “by the sweat of your brow you shall eat bread.” Cain’s offering to God is “from the fruit of the soil”- unspecific, but Crumb shows it as a basket of grain. (Jacob is also shown pounding down what might be grain or flour with his mother- is Crumb using Esau’s skill in hunting to set up a parallel?) The meaning of all this would take us into Biblical analysis, but Crumb has helped guide us to these issues.

“The stated “literalness” of Crumb’s adaptation as well as its generally bland imagery will lull many readers into the false impression that Genesis intends a deep consideration of centuries old biblical scholarship. It doesn’t, an important point which I will address in more detail later.“

It gives me the impression that he intended to consider the Bible. I don’t see how later scholarship is suggested, and surely Crumb wasn’t surprised to read these lines on the inside front cover: ”Using clues from the text and peeling away the theological and scholarly interpretations that have often obscured the Bible’s most dramatic stories, Crumb fleshes out a parade of biblical originals.“ This is an important point which I will address in more detail later.

I pointed out some interesting things in Crumb’s depiction of God in the comments section over at Blogflumer, and defended it as the kind of subtle commentary and exploration of the text that people are claiming he doesn’t make. To address some of your points here:

You claim that this line in Crumb’s notes: “after closely reading the beginning of the Creation, I suddenly imagined an ancient man standing on the shore of a sea, and gazing out at the horizon, and seeing only water meeting the sky”- is “an explication of his choice to so portray the Almighty.” It’s not. Crumb’s “ancient man” is not God, but to a man of ancient times trying to figure out his world. Crumb is describing the Hebrew vision of the universe (diagrammed here: http://io9.com/5586362/a-scientific-diagram-of-the-ancient-hebrew-cosmos) and speculating about how they might have come up with it.