It is rare to see an adaptation come under attack from followers of the original for being too faithful. Dramatizers regularly compress and invent for what they hope will be the strongest statement in another medium, then defend their interpretation as being in the spirit, if not the letter, of the source. The devotees’ essential reply is that the failure to respect detail, or honor the letter, lost the spirit, leaving some creature that had no right to go out under the same name. Did the adapters think they knew better than the writer?

That secular attachment is a pale, fleeting image of what the Bible can mean for readers, yet here we have seen some furious attacks on a groundbreakingly faithful treatment. People with long relationships to the original are insisting that the Book of Genesis demanded an interpretive, even editorializing approach. According to one critic, the Bible is right there if anybody wants to read it. R. Crumb’s The Book of Genesis Illustrated needed to reshape and select its material. The artist should have pushed his opinions in front, even lampooned it because that’s what he does, and instead gave us a boring, stodgy, completely unnecessary work that never, ever should have been made. (Though why is the mirror-universe review so easy to write: “Had Crumb been able to restrain his clowning urges, he might have learned a ‘“not-so-” secret’ that we who know the Bible have known for years of watching these acts go by: nothing could have been more shocking than a straight adaptation.”)

Given the deaf ears turned to it in these discussions- the point is denied until corrected, then was never at issue and isn’t important anyway- the pioneering nature of a comprehensive illumination bears repeating up front. As Crumb told Comic Art Magazine at the outset of the job,

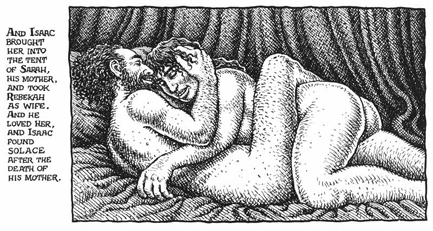

“I’m going to be doing all fifty chapters of Genesis, including every word. Straight from the original- I’m not leaving out anything… you’ve got to do an extremely close reading. It’s really interesting and full of surprises, what is actually in there when you read it closely. And, you know, believers tend to gloss over the stuff that makes them uncomfortable or that they don’t get. But it’s in there, you know, so it’s going to be illustrated, so…”

But such a believer is not the serious student of theology, who wrestles with these problems until they grant him understanding. Crumb prepared for heat from religious fundamentalists, who claim the Bible as literally true history, instruction, prediction, and absolutely present a major cultural force that would be foolish to ignore (“If I’m going to be doing this and don’t want some Christian fanatics to kill me, I’ve got to say ‘Look, it’s all in there, I didn’t change a single word, it’s in your holy book…’ so we’ll see if they want to kill me or not,”) but this left his flank open to condescension from those who are dedicated to exploring its deeper meanings. Another commenter:

“Part of the problem I had… [was] the overly literal interpretation and complete lack of insight about the actual ideas underlying Genesis. Virtually all scholars, rabbis, clergy etc. in the modern day, even those with more fundamentalist leanings, use the bible as a starting point to interpret the metaphors and stories and apply them to the modern day… Yet I would suspect that very few, if any, clergy believe in the stories as literal, historical facts.

“Thus, the depictions of God as an old man, the creation story, etc… represent a very childish understanding of Genesis. That would be fine if this were a children’s book, but the problem is that by presenting the entirety of the dense text… no child will be able to penetrate this book either.”

We can all understand how a treatment could cling to the letter, lose the spirit, and end up flat. From Ng Suat Tong’s essay, posted here on July 14, a reader might get the impression that Crumb has given us a soulless, mechanical transcription that recycles Sunday-school figures (a white beard, a cuddly Garden of Eden) and only superficially engages the work it was based on. It’s easy to take Suat’s accusations of a lack of intellectual and spiritual involvement in Genesis in a still essentially worldly sense, and a genially agnostic member of the public might see no harm in letting the religious and literary meanings blend. But his fault-finding refers to a lack of dedicated application in a religious framework that none of us should wish to see confused with the “soft” intellectual and spiritual experience of a great book.

(I gave a detailed response to his points in the comments thread for his essay, which was collected here.)

The overriding problem is his persistent call for Crumb to do something with his adaptation that he’s not trying to do. Suat’s characteristic complaint is that Crumb fails to explicitly incorporate centuries of Biblical scholarship, for which the evident rejoinder is that these were not books he chose to adapt. As just one example,

“In response to Genesis 3:15… we get a somewhat cursorily drawn snake wriggling away. It is common knowledge that Christians look upon these verses as the protoevangelium (for example, some church fathers saw the ‘woman’ here as the virgin Mary and the ‘seed’ as representing the church and/or Christ in particular) while Jewish commentators sometimes view the ‘seed’ as a metaphor for humankind. There is little evidence of a response to these or any other interpretations here.“

These objections are so consistent they have an emergent property as a fairly clear request for a comic that would travel through Genesis (if it got out of Eden) with a chemistry of text and symbolic imagery, discussing the interpretations of the ages. Perhaps some cartoonist out there is looking for a project. A highly routine style of Biblical adaptation that tricks out the narrative with new scenes and dialogue could also work in some scholarship (again, we can hear the response: “Crumb’s is the latest in a long line of reworkings of the Bible,”) but this was not his project either. As he told The Paris Review,

“In all the comic-book versions I was able to find, they just made up dialogue, pages of it that are not in the Bible. I was reading this one thing and I thought- did I miss this? And I went back and checked against the text and it’s not in there. And they claim to be honoring the word of God, and that the Bible is a sacred text… the most significant thing is actually illustrating everything that’s in there. That’s the most significant contribution I made. It brings everything out.”

But let’s be fair and remember how it all started: some remarks that Crumb’s achievement was past most critics as it demanded Biblical and cartoon expertise, was a significant exegesis, and an important work of art. This set Suat to assessing whether it “could not be ignored” in connection with the art and literature surrounding the Bible- raising the bar quite high, since most believers don’t even read the Bible from cover to cover- and the effort blurred hazardously into a judgement on what the book was good for, period. But he brings more to the table than just confusion about what a significant visual exegesis would have to be like.

* * * *

Crumb’s work explores and attempts to reconstruct the cultural life of Genesis as a literary, historical, and spiritual work on its own terms. It builds on scholarship, mostly that of Robert Alter, who composed a poetic modern English translation from the more exact and nuanced understanding of the ancient Hebrew contributed by modern philology, and wrote an extensive and insightful commentary that built on the analyses of modern Biblical scholarship, but also addressed older (mostly Rabbinic) commentary.

The tendency of modern biblical scholarship to pull apart narrative threads has been disintegrative to the religious sense of the Bible as a unified, divinely inspired whole. This does not mean these writings had no unity, as they were assembled and revised with an editorial/authorial vision. Crumb’s approach is fundamentally integrative, creating and testing a dramatic and psychological coherence. It takes an exploratory attitude to the ancient text. Instead of imposing his own shape, Crumb allows the peculiar narrative shapes of the ancient folk tales woven into Genesis to emerge. He can bring out subtle parallels, irony, and humor difficult for the modern reader to grasp. The strict adherence to the narrative can at times lack the kind of momentum we’re used to (though not that often) but if the reader is patient he will find surprising payoffs.

The original audiences for these tales had an understanding and shared context that we have lost. Crumb subjected the text to a rigorously close reading and made a solid attempt to visualize the largely conjectural cultural setting (laying out his methods, which I haven’t heard anyone challenge, in the introduction.) His adaptation must be regarded as an experiment, in painting a full picture from a collection of hints, and such totality cannot have the exactness of scholarship. But he offers a tool to the reader who hopes to engage in the great detective work of piecing together what it all actually means.

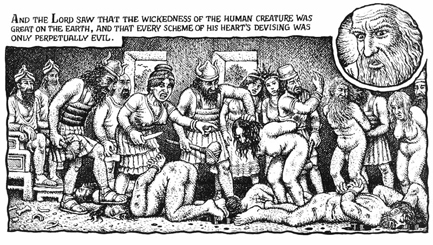

His work has an editorial dimension, as in the dramatic tension of showing figures like Noah’s or Abraham’s ambivalence to the sudden invasions of their commanding deity, or in scenes like the tableau of humanity’s wickedness before the Flood. In his New Republic review, Alter reproves that display for settling on only one possibility, but fails to note that, despite the exoticism of the costumes, Crumb is showing us a war crime, strongly reminiscent of the kind of thing we hear about in the news. It suggests we didn’t get any better.

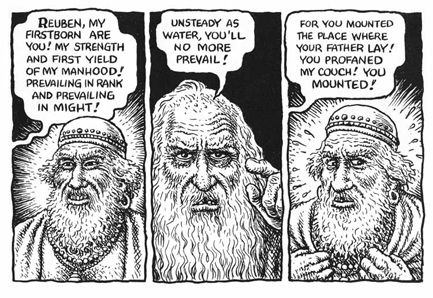

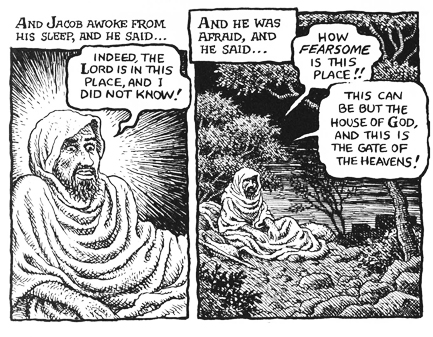

The scene of Jacob’s prophecy to his twelve sons gains a dramatic force and psychological interest that it cannot have in text alone, where its poetic nature, one of the oldest pieces of writing in the Bible, is much more apparent. In this format, the ease with which the reader can compare the faces and reactions of his sons to the deeds of their youth restores some hint of the fullness that an audience who knew these tribes would have felt here.

The exposition can “test drive” explanations for mysterious passages (many of which, Alter’s reservations aside, were likely not intended to have the effect of hovering between possibilities he describes for their listeners.) From Alter’s review:

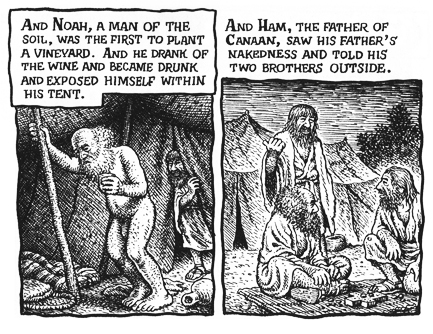

“One of the most famously enigmatic moments in Genesis comes when Noah has drunk himself into a stupor in the aftermath of the Flood and ‘exposed himself within the tent. And Ham the father of Canaan saw his father’s nakedness and told his two brothers outside.’ Exegetes for two thousand years have been trying to make out exactly what transpired between father and son.”

In his notes to the book, Alter goes over such possibilities as rape and castration and finishes by saying:

”It is entirely possible that the mere seeing of a father’s nakedness was thought of as a terrible taboo, so that Ham’s failure to avert his eyes would itself have earned him the curse.“

Or it could have been disrespect.

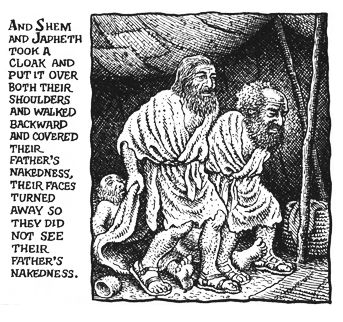

Crumb offers, to my mind, a persuasive support for the view that Ham’s offense was simply seeing his father naked. Ham grins as he peers inside and seems to guffaw as he speaks to his brothers. He is not just breaking a taboo, but mocking the weakness of a old man. A minor act reveals a meanness in his character, and his attitude is strongly contrasted with his brothers’ in the memorable next panel. Whatever the original taboo may have been, Crumb has brought the psychology of the scene to light.

Contrary to opinions we’ve been hearing, this image also shows that Crumb has a grasp of the sacred.

* * * *

The claim that Crumb’s interpretations are childish appears to find its surest footing in the portrayal of God. Here, Crumb has undeniably chosen to guide us through Genesis with a blunt, provocative device. Its literalism has attracted more fire than any other feature; after all, we moderns are smarter than that. We know how “God spoke to…” could mean so many things.

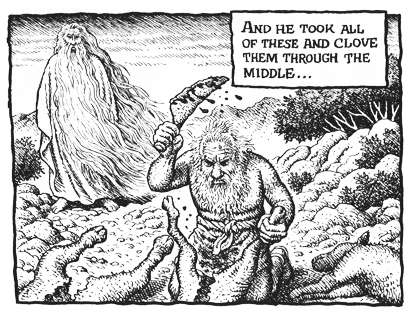

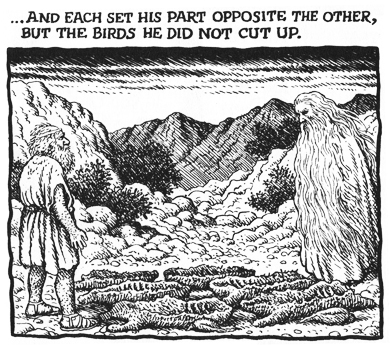

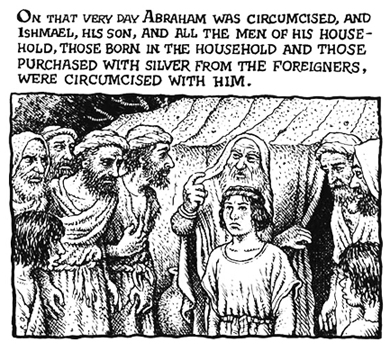

But scenes like Abraham’s ritual with him are more discomfiting, to the modern mind, than seeing Abraham chewing on a hallucinogenic plant to have his encounter would have been, or an even starker scene with him following the instructions of a disembodied voice in the wilderness. The striking feature is the way God seems so physically present. His feet are on the ground.

This puts me in mind of two peculiarly modern exchanges: between a person who suffers from hallucinations and an average person, who will be surprised to hear that the figures or voices seem truly real, his having always assumed them to be more like intensified thoughts; and between a lay and religious person, when the lay person asks, “Surely no one in this day and age literally believes that ________…” and quickly learns he has made a mistake. The way this God is right there recalls a side of human experience that we have no reason to believe will be making a quiet exit any time soon.

* * * *

Parts of Genesis are already well ingrained in our culture, and Crumb’s literal renderings are thus familiar. I’ll give the detractors something: the most famous scenes are solid, but often uninspired. It’s in the unfamiliar scenes that Crumb shines, giving us a wealth of invention, insight, and spirit, and I don’t think that’s a subjective judgement based on their novelty. Noah’s flood has the necessary set-piece panels. Abraham’s bargaining with God is acted appropriately but lacks the dread and mystery that an imaginative reading of the text can have (though “not as good as imagination” may be impossibly demanding.) Jacob’s wrestling with the mysterious visitor does just look like two men wrestling, although this might have been the idea. Eden itself is refreshing in its newly accurate elements, and persuasive psychology, but it’s hardly an attempt to take on the great field of portrayals in Christian art.

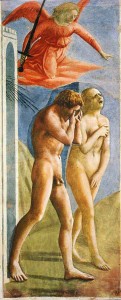

Anybody who wants to set up a competition with museum pieces can run an image search and make comparisons that leave Crumb in the dust for limpid imagery, light, color, detail, etc. To be useful, however, these must be mindful of the artists’ goals. There are problems with comparing one panel taken out of a comic book with the summary that a painting represents (even among the concert of scenes in the Brancacci chapel), but one of Suat’s comparisons does highlight a difference in tone:

“Even those possessed of untutored eyes should be able to see the difference in ability and insight at work here. Masaccio’s Expulsion may be deficient in textural fidelity but its spiritual immersion cannot be disputed. The rigidity of Crumb’s chosen style in The Book of Genesis makes it difficult (he does succeed occasionally) for him to adequately convey anguish, pain or psychological depth in isolation from the text.”

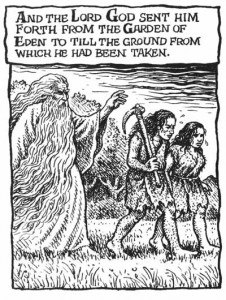

Should we judge two Hamlets by how much emotion each one gave a certain line? The Massaccio is more anguished, but consider what he was painting: grief, wrenching separation, and a universal fallenness that would only be solved by the advent of Christ (who appears in the painting immediately to their right). If Crumb intended to echo it, he gave us a wry counterpoint. Crumb has drawn the happily naked couple sent out with heavy, unfamiliar clothes and tools into a hard new world. Their discomfort shows in comic-strip sweat, and God is calm, like a boss who’s given the necessary dressing down and says “Now get out of here” almost gently. He sends them off with the open hand he’s used to arrange creation, not pointing as he does on the more emblematic cover. Crumb might well see the scene it as a pattern for life, like Massaccio, but the tone is “that’s how it goes.”

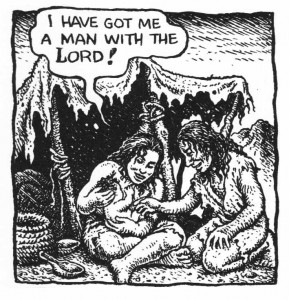

There is some anguish in the preceding panels, and the next image, of the couple’s joy over their child among their rough tools, is moving.

This brings us to a subjective area. Suat says, ”I wasn’t moved at all by anything in this comic adaptation.” Then again, he’s “just not a very emotional reader when it comes to Genesis.” This could be explained by another critic’s summary of the human element of the book as an exhibit of the amorality and violence of man before the introduction of the Decalogue, which strikes me as dismissive to the characters. Anyway, Suat’s description of engaging with it on a more intellectual level sounds like an admission that he may not be the best critic to evaluate the human drama.

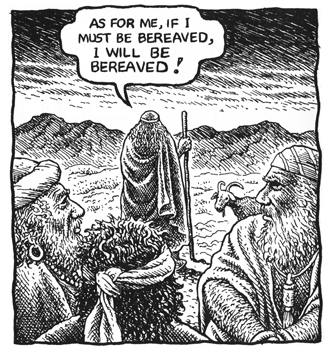

Following the characters through their lives and seeing them age over the course of the book (strangely rare in comics) is itself cumulatively affecting. The Shakespearean (well, Biblical) pathos of seeing men face their greatest challenges in old age is emphasized throughout. Crumb’s was not just a mechanical surface reading but a deep involvement with the identity and journey of the characters. He had to create likenesses for them and live deeply in their stories to make their journeys credible, etching each face and detail in monkish isolation.

Iris Murdoch wrote,

“Art is not an expression of personality, it is a question rather of the continual expelling of oneself from the matter in hand. Anyone who has attempted to write a novel will have discovered this difficulty in the special form which it takes when one is dealing with fictitious characters. Is one going to be able to present any character other than oneself who is more than a conventional puppet? How soon one discovers that, however much one is in the ordinary sense “interested in other people,” this interest has left one far short of possessing the knowledge required to create a real character who is not oneself. It is impossible, it seems to me, not to see one’s failure here as a sort of spiritual failure.”

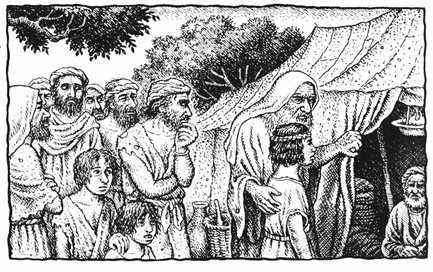

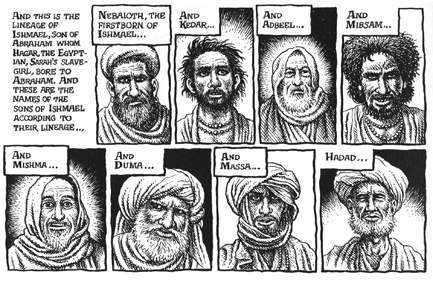

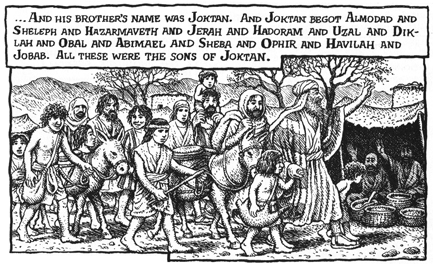

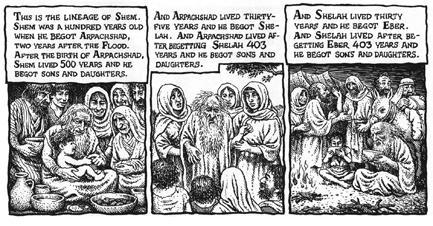

The book’s signature touch is its staggering wealth of quotidian detail. The lives and communities cased in single panels, the moral stamp on each face in the headshots, give the genealogies a weight that is hard to analyze but ridiculous to deny. This is more than the eye candy for bored readers (“This is all there is to Crumb’s comic? A vivid reimagination of times past for those who find the original text dull and tedious?”) that Suat describes. It is a grand narrative of man’s beginnings and proliferation, and the place where what I think is the moral core of Crumb’s treatment, his humanist theme, manifests.

“…requiring spirituality from Crumb in relation to Genesis is an exercise in futility, but that’s only one option among many.”

“Hajdu wants Crumb to add a spiritual dimension to his reading of Genesis, something which is clearly irrelevant in the context of creating a fine adaptation based on modern day archaeology or biblical scholarship …Crumb lacks a certain spirituality which is equally of no consequence to this project, since Crumb is far more interested in the historical and mythological aspects of Genesis (i.e. not a journey of the soul but one of personal discovery.)”

Suat consistently treats a theological approach as essential to a serious adaptation, and judges the book by its absence.

“It should also be noted that Crumb (a self-proclaimed Gnostic) has little interest in Genesis as a religious or sacred text, a tremendous hindrance in adapting a book which has been largely interpreted in that context.”

This is almost defensible. A view through the lens of centuries of interpretation, especially Christian, is often what we really mean when we talk about “the Bible.” We should be mindful that the Bible (singular but derived from the Latin and Greek biblia, “books”) is itself a product of scholarship: a collection of writings, including commentary, that was compiled, edited, and reinterpreted with the passage of time, also added to, before a line was finally drawn between the book and later interpretation. Until comparatively recently, the need to find coherence, correct belief, and meaningful address to the reader’s own time was driving Biblical scholars as much as it did the original composers. They never stopped writing it.

Christian scholarship particularly depended on the discovery of cryptic layers of meaning beneath the literal words. St Paul’s comments on Mosaic law in terms of “the letter” (“Who also hath made us able ministers of the new testament; not of the letter, but of the spirit; for the letter killeth, but the spirit giveth life”) evolved to describe ways the Hebrew Bible needed to be read: in the “letter,” or surface meaning, and “spirit,” or various kinds of Christian signification (which encouraged the false impression that Jews took it strictly literally.) Certainly the Garden of Eden story encourages an allegorical reading, but even a more palpably located event like Abraham going out from the city of Ur might be seen as a journey of the soul. And even at a time when the letter’s historical truth went unquestioned, it was considered inferior.

It would be as unfair to describe Suat’s approach to Genesis as picking through the text for Christian parallels as it is for him to say an irreligious person would only see the Garden of Eden story as “poppycock” (though I haven’t been reading those New Atheist books.) It appears to work it into an overarching structure of spiritual inquiry. But he does connect with that disdain for the “letter”:

“Now much of Genesis can be read as a very flat “history” of the origins of the Jewish people but this robs it of much of its subtext and thus underlying power. Genesis has very little to do with history as we understand it today.”

Curiously, a comment quoted earlier also slights the writings in themselves, from a Jewish perspective:

“Virtually all scholars, rabbis, clergy etc. in the modern day, even those with more fundamentalist leanings, use the bible as a starting point to interpret the metaphors and stories and apply them to the modern day… Yet I would suspect that very few, if any, clergy believe in the stories as literal, historical facts… Teenagers are much more interested in exploring identity issues, spirituality, history, ethical issues and religious culture than they are in text studies, and even if there were a few willing to do some in-depth text study, Crumb’s book would be the last place they would start. There are literally hundreds of better books, websites and other resources that would offer more insight than Crumb’s Genesis. I think the book’s only real value is as an art book. In my mind it has no religious merit whatsoever.”

I don’t mean to pick a fight with everybody on the internet, but I wonder: why would he assume a reading that does not apply these stories more visibly to present interests could only concern their historical fact; and why should a non-interpretive adaptation (as elsewhere, Crumb’s can be fairly called interpretive, but this is the “so you see, Timmy…” sense) of the first book of the Bible serve only as “text study”- touching nowhere on identity, spirituality, history, ethics, and religious culture? This is a disparaging attitude to literature. (While it’s not the only standard, I can easily imagine a teenager taking an interest in Crumb’s book, and, indeed, asking questions. Like Suat’s, the point is that we mustn’t go near the Bible without professional help.)

In this sense, Crumb’s adaptation is thoroughly in the letter. But the lack of effort to unify Genesis with later tradition hardly means that his handling has no moral, psychological, intellectual, or spiritual- in other words, literary- interest. It is strange that an alert, sensitive, and rigorously faithful adaptation is being treated as if it must lose all the “subtext and power” of the original, and be devoid of any deeper engagement.

Here the religious perspective is laying claim to the metaphorical, intellectual, and spiritual levels of the text. Assuming that the real “intellectual meat” of Genesis was staked out by scholars who used it to help construct a theology is anyone’s prerogative. If you adhere to the view that theology is critical for a true engagement with the text, then Crumb’s scene-and-character-sensitive construction of a credible world from Scripture alone (with the help of modern Biblical criticism) clings to the letter in a crude, childish, even insolent way.

But a critic who feels that way needs to let us know from the outset. I might have liked to have seen in Suat’s review that he regards Genesis without that structure as being a “flat history of the Jewish people,” also that he lacks interest in the human drama, but I read it in the comments section. How the adaptation strikes him as a __________ would have been a fine subject for a more searching essay, and I’ve been harsh here, but I would have read it.

A literary endeavor can often teasingly resemble a religious one, because so many of the ways we relate to literature are descended from religion. What’s dangerous about treating any depth in Genesis as if it lies in the theological edifice of later times is that, if the critic doesn’t tell us which values he’s bringing to bear, it can sound very much as if he’s saying that a treatment that fails to engage with that edifice isn’t engaging with it on levels we commonly understand literature to have.

* * * *

We shouldn’t be too dismissive of the beginner, or the person who might find Genesis easier to enter through a work like this. In our culture, if the curious secular reader isn’t thrown off by the “begats,” he probably will be by the ritual commands beginning in Exodus, and if he picks up again it will likely be in the Gospels or Book of Revelation. When a person on a religious path picks up the Bible, he usually has a highly refined structure in place to guide him to meaning, whether with explanations from professional interpreters or training in determining meaning within a certain belief system.

The hostility we have seen to a faithful adaptation suggests that Crumb’s work threatens to interfere with structures people have developed from Genesis. But why should it? It’s not at all clear that any of Crumb’s choices forbid them, aside from his portrayal of God, which has been roundly dismissed as obtuse. (Regardless of all the digital ink we’ve spilled on the subject, the point of this God is to treat him as a character, who emerges with tantalizing hints of a personality and agenda. It’s possible that for the theological student, this may not be the best first step on the ladder to a spiritual understanding, but other aspects might.)

Crumb’s remark about the absurdity of basing one’s life on Genesis is one of many he has made that show his personal involvement and variety of feelings about the project. Maybe we’re not dealing with much more than the fear that it will hold the text up to ridicule and dismissal. In fact, it is more likely to invite a modern reader in. Crumb’s work can serve to cut through the arrogance of modernity and captivate a reader who would have been likely to dismiss the text as an irrelevant artifact, and set him on a path to better understanding his culture and himself. This is my own view of the importance of the Bible, since I myself am not religious, but who knows what leads to God.

____________

Note: This is part of an ongoing discussion of R. Crumb’s Genesis. You can read the whole series here.

I think this is a beautifully argued rebuttal both to Suat’s and Robert’s thoughtful critiques, which to me both seemed somewhat insensitive to Crumb’s visual interpretation. On the surface he may not seem it, but he is fundamentally a humanist, deeply engaged in the portrayal of human beings and their behavior, for which he uses a unique blend of observational, mimetic drawing and cartoon shorthand.

As you point out, there are many moments of subtle psychological insight in his interpretations in Genesis, and it is on the basis of these, rather than any intellectual/theological contribution he might have that it should ultimately be judged, I think. Again: as I believe I’ve written somewhere around here before, art is art, not theory (or theology).

Suat’s comparisons with some of the great visual interpretations of the text in Western art was, I think, instructive in a number of ways unrelated to his intentions with them. Firstly, he juxtaposed them with Crumb almost without comment, as if assuming it to be obvious how much greater they are. They may well be (in fact, I agree that most of them are) but I find this tactic patronizing and unhelpful. Almost as if the object is to crush this work of lowly cartooning with the redoubtable weight of the Western canon. We know these works of art to be great and will therefore hesitate before challenging the implicit argument.

Secondly, it’s a problematic juxtaposition because most of those artists are going for something different than Crumb (I also found Robert Alter’s invocation of Tintoretto entirely useless, even misunderstood) — Masaccio made sense, but a comparison with various medieval representations, with Giotto or with Brueghel would be much more apt, and better illuminate the limits of Crumb’s interpretation when considered on its own terms.

As for the ‘white-bearded patriarch as God’ I don’t get the beef. That’s the most consolidated visual archetype and thus the one that serves his ‘straight illustration job’ best. It’s the most ‘neutral’ way to go, in a sense, while at the same time raising the question of why we have this archetype.

A really smart essay, perhaps the best analysis of Crumb’s Genesis to appear so far, and certainly the best critical writing ever to appear in Hooded Utilitarian.

A agree with Matthias that Suat’s original tactic of juxtaposing earlier paintings and drawings of Genesis with Crumb’s work was “patronizing and unhelpful”. This type of justaposition might have served a useful function if Suat has been mindful of 1) the formal difference between a painting and a comic strip drawing and 2) alert to the historical differences between the early 21st century and previous eras. But his post was bluntly ahistorical and unresponsive to the way comics work as comics.

My only regret about Alan Choate’s essay is that it is framed as a reponse to Suat’s piece, and therefore spends a lot of time grappling with non-problems or trying to justify Crumb’s work using Suat’s ill-fitting framework. One example: for Suat “spiritual” is a term of praise, something inherently good. But I have to say, for me part of the great achievement of modern Biblical scholarship (which informs Robert Alter’s translation and thus indirectly influenced Crumb’s work) is that is not spirtitual (i.e. it doesn’t try to tailor everything to fit a pre-existing theology) but rather historical and philiological (i.e. trying to understand how this ancient tephilologicalxt actually got composed and what the words might have meant in their original context).

Not everyone believes in God or in the idea that the Bible is a divinely inspired text, and there is no reason why orthodox religious believers should have a monopoly on reading or interpreting the Bible.

“and certainly the best critical writing ever to appear in Hooded Utilitarian.”

Oh come now. There’s no reason to damn with faint praise.

Alan,

A really great piece. I think the kind of comparison method that Suat uses can be fine, but Jeet’s right that it’s important to acknowledge differences in generic and historical conditions. In short responses to Suat, I used something like the approach he did, but tried to stress differences, especially those between Blake and Crumb. I think, as Matthias says, some critics assume that, when put next to work in the Western canon, Crumb’s visual and conceptual poverty will be inarguable demonstrated. I think that the comparative method can show the opposite: the ways in which Crumb succeeds. He has a very clear philosophy behind his choices, and Alan deals with the details of Crumb’s vision in a way that his critics have not.

Matthias – do people actually say that Crumb isn’t a humanist or is it just something that isn’t talked about much? I wouldn’t have thought it would be an open question; it seems so obvious…

Alan, thanks for this piece, and for putting so much thought into this.

Jeet, I think this is a pretty interesting response.

“My only regret about Alan Choate’s essay is that it is framed as a reponse to Suat’s piece,”

That actually rhymes well with one of Alan’s main points in the essay, which is that Crumb should not be required to engage in the conversation about the text, but should instead be free to present the original mediated only by his own sensibility and instinct. Similarly, Jeet sees the essay as limited by the conversation it came out of. forced to deal with uninteresting side issues rather than with the main thing (presumably) the text itself.

As I’ve said before, I’m more sympathetic in general to the idea that critical conversations are essential to criticism and to art. It is interesting though (at least to me) how central this argument about the worth of arguments seems to be.

Caro, I don’t hear it discussed all that much, in fact there’s surprisingly little criticism of note written about Crumb.

I guess the reason calling him a humanist might surprise people, is that so much of his work seems to project this at times almost nihilist contempt for all kinds of people — he has with some right been described as a misogynist, a racist, an anti-semite, etc., and admits as much, describing himself as an equal-opportunity offender.

But underneath all this, it seems clear to me that his work is informed by a deep interest in human beings, and his drawing is healthy, almost wholesome, despite his often transgressive subject matter. A great example of exorcism through art.

Most of Crumb displays a deep interest in himself–insofar as he is a human being, I guess that makes him a humanist.

“exorcism through art…” –yes–but this seems like one of art’s least important purposes to me… He could have exorcised his own demons without publishing it, one would think. Crumb’s work certainly has value to him and his neurotic psyche–but the value to his readers/viewers is less clear.

He is an absolutely amazing draftsman.

However, the misogyny, racism, anti-semitism, etc. makes the humanism argument somewhat unviable. How many “humans” are really left after so many have been alienated and stereotypically condemned.

Ah, in this context, I automatically filled in “secular humanist” which seemed obvious — but really isn’t the contentious bit. I look forward to Eric and Matthias playing this debate out!

Noah, have you investigated The Manga Bible enough to know whether it engages with the source material more or differently? The Archibishop of Canterbury apparently approves…

I see a real tenderness in some of Crumb’s work, an affinity for the people he draws.This is certainly true in Genesis, which has many subtle and dignified depictions of biblical characters and scenes. For a statement on the cartoonist’s humanism, Genesis could be the key work.

Yes, I agree — he’s not merely interested in himself, and when he is, he usually has something resonant to say about himself.

As for his more transgressive work, it’s true that it’s often hateful, but not unequivocally so — he often embraces prejudices in ambiguous ways, as if he trying to figure out how they work. It’s clear that there’s a conflict in his work between these aspects of his work and this more genuine interest in people, but ultimately they are of a piece. And certainly in his later work — and beautifully in Genesis — his humanism has become more apparent with the transgressions of yesteryear seeming of less interest to him.

What I mean too, is the affinity with which he draws people, even in throwaway strips — he as intensely observant artist with a passion for the physical world.

Oh, and I’ve looked at the manga bible, which I found vapid and pretty awful.

———————–

eric b says:

Most of Crumb displays a deep interest in himself–insofar as he is a human being, I guess that makes him a humanist.

…However, the misogyny, racism, anti-semitism, etc. makes the humanism argument somewhat unviable. How many “humans” are really left after so many have been alienated and stereotypically condemned.

———————–

Does Crumb praise “misogyny, racism, anti-semitism”? He may explore those attitudes in his work, even delight in them, yet remains aware that they’re wrong, for all the appeal they may have.

From dictionary.com, some definitions of “humanist”:

———————–

a person having a strong interest in or concern for human welfare, values, and dignity.

a student of human nature or affairs.

———————–

A “humanist” need not be someone who thinks only the best of humanity, creates only “inspiring” stuff; but who finds the species and its behavior the most fascinating subject for study and exploration.

I want to address a couple of points here before (if) I jump into that other conversation.

Jeet: Thank you for the high praise. I probably should have dealt more concisely with those critics and sharpened my look at Crumb- it’s not quite sufficient as a general interest look at the work.

If I was going to use a term like “spiritual,” I should have separated what I meant more clearly. I think the word has expanded into secular areas, and not always in a silly or useless way. I do think Crumb’s effort can be helpful to evaluate on that basis. There’s his career interest in spirituality – you know it, but I’ve been meaning to mention it to some people here- and I think it can still be legitimately used to describe a serious act of labor that leads to a deeper appreciation, like Crumb’s. At least, the comparison to a monk’s labors, and Crumb’s use of “illumination,” seem appropriate.

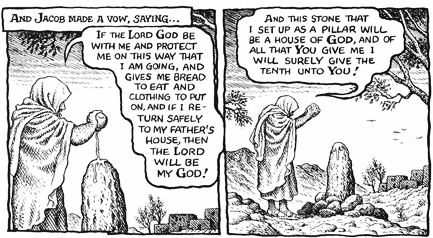

The book is interesting as a long-form work because the tone changes. The editorial/satirical edge is gradually absorbed into a deeper involvement with the increasingly character-based narrative (and when humor emerges later, it’s brought out from the stories.) There’s a difference between the Hammer movie-treatment of “this was the time when men began to call on the Lord”, and the panels I posted of Jacob erecting his first altar, which I think are sensitive to that attitude of devotion- and I think the Joseph story reflects a deep involvement.

In the most literal sense, “spiritual” is appropriate to refer to aspects of a book that reflected & developed the religious/spiritual sensibility of these ancient Hebrews, and for Crumb’s efforts to explore that.

Noah, you write: “one of Alan’s main points in the essay, which is that Crumb should not be required to engage in the conversation about the text, but should instead be free to present the original mediated only by his own sensibility and instinct.”

I was actually trying to say that, far from following his instincts in the woolly way that Suat described, his choices were informed by a serious reading of the text, and supported by scholarship- Robert Alter’s commentary, which, if you’ve seen the book, is extensive, in-depth, and synthesizes the insights of a variety of fields of scholarship.

Crumb’s choices are thoroughly founded on the information in Alter’s commentary. This is a major feature of Crumb’s book that I don’t think I’ve seen pointed out anywhere, and I should have described it more clearly.

Alter himself doesn’t comment on the extent to which Crumb builds on his commentary- I wonder if he thought it would come across as laying claim to his accomplishment. In fact, it impresses me more, to compare the books and see how Crumb responds to it. I recommend Alter’s Five Books of Moses to anybody who enjoyed Crumb’s book or who wants to seriously evaluate it.

Also, I think Crumb absolutely does engage in a conversation about the text- not by saying, “Look at me, here I am with opinions about the Bible-” but by offering a tool- a faithful, investigative treatment- that facilitates such conversations.

Finally, I’ve thanked Noah via email but I want to publicly acknowledge his help in offering me a platform for this essay- it encouraged me to try to make this into more than the usual comments-thread war. I also want to thank Suat for his inspiriting essay and continued good humor.

And thanks, everybody.

Wow. This discussion certainly exploded, particularly after Suat’s response. I’d like to reply to a few things Alan wrote here in his original piece.

Attacking adaptations for insufficient fidelity to the original is a fairly recent phenomenon, one that can probably be traced to the rise of mass-media reviewing. Pauline Kael surmised in her review of Stanley Kubrick’s film adaptation of Lolita that much of it is likely due to a compulsion on the part of reviewers to create a pretense of erudition. Ironically, this sort of posturing works against that end. It automatically assumes that the adaptation is trying to replace the original, which no adaptation intends to do and almost never achieves. (In the instances where one effectively has supplanted the original, such as with Spielberg’s film adaptation of the Peter Benchley novel Jaws, the original wasn’t particularly worthwhile in the first place.) This tendency also displays an obliviousness to the history of the arts, where adaptation has been a constant all but from the beginning. Fidelity to the original hasn’t traditionally been a criterion of value, and many adaptations, such as Euripides’ Electra and Chaucer’s Troilus and Criseyde, present, at least in part, a satirical view of their sources.

Your mirror-universe version of my review is amusing, but it’s not one I would have written. Adaptations that don’t transform the original in a significant way are largely worthless in my view, at least in terms of their value to the public. Crumb’s Genesis strikes me as an extremely self-indulgent exercise, comparable to my own (far less labor-intensive) project of translating Dante’s Divine Comedy into English. I find it rewarding, but I don’t expect anyone else to. I’m certainly not (unlike Crumb) marketing it to the public through the most prominent literary publisher in North America, publishing excerpts in the continent’s premier literary periodical, or sending my agent out to tell the press that it’s my likely masterpiece.

Why is a comprehensive illumination of a work a significant accomplishment in and of itself? How many notable works have received a treatment of this sort, and do we really feel the lack with those that haven’t? Honestly, how often have we felt the lack with those that have? Crumb seems to think that next to no one knows Genesis except from adaptations, and that is definitely not the case.

Crumb’s concern about a hostile response from religious fundamentalists is either misguided or a red herring. I can’t think of an instance in my lifetime where Jewish authorities were publicly upset about an irreverent treatment of material from the Torah. Christians have only gotten upset about what they see as demeaning depictions of Jesus or the Virgin Mary, and they seem to have come to the conclusion that it’s probably best to just ignore them. It’s hard for me to imagine a Christian fundamentalist not finding The Da Vinci Code extremely offensive, but you didn’t see them raising much of a stink about it, either. And in the instances where Christians have loudly protested, it’s usually been a commercial boon for the work in question.

I’ve got to go. Hopefully I’ll find time to say more.

Hey Robert. The faithful adaptations and mass culture seems right…though I bet it’s less reviewers fault and more the mass audience itself. Especially with films and hugely popular books, I think people just aren’t interested in seeing a new take — they want a repeat of what they already like. Reviewers and audience tend to have similar expectations, I guess; they do influence each other, but it goes both ways.

The point about Christians being unlikely to be mad seems right too. It’s especially hard to see why they’d be upset when Crumb’s work stays so close to the text.

“It’s hard for me to imagine a Christian fundamentalist not finding The Da Vinci Code extremely offensive, but you didn’t see them raising much of a stink about it, either.”

There was tons of reaction against it. CBN devoted a special to it and Pat Robertson often talked about it on the 700 Club. Jack Van Impe repeatedly railed against the book and movie as did many other televangelists, minsters preached sermons against, Christians and Catholics picketed and protested, a number of books and DVDs were published about the “hoax,” debunking websites created, and many mainstream media outlets carried stories about the hostile reaction.

Yeah; there are actually Christian groups that were completely freaked out about Harry Potter too, of all things.

The fact that Crumb’s version hasn’t caused much (any?) blowback is an indication that it’s much less offensive than he thought it was, and/or that it’s not sufficiently popular for those folks to bother with.

On another thread someone said Crumb based his text on the King James version of the bible and used this to to condemn Crumb as a conservative. But Crumb mostly used Alter’s translation, and didn’t take much from KJV — he says this explicitly in the first line of his introdution.

Though I like the book, I have no problem with people not liking it; we have different tastes and see different things in it. But getting basic facts wrong about Crumb’s past work, the book itself, or the cultural context in which it might be read and using them against Crumb is a mystery to me. It weakens what could otherwise be a strong and interesting argument against the book.

“Yeah; there are actually Christian groups that were completely freaked out about Harry Potter too, of all things.”

I have had students who refused to read it in my children’s lit classes . . .

“that it’s much less offensive than he thought it was”

Did he say this? The following interview with Crumb idicates something else: “I had no idea how they would take it.”

“But, as far as, like, how people react to my version or… I said in a lot of interviews that I had no idea when I was doing it how people would take it. I knew that probably some of the Crumb fans — it’s really true here in France, even more so in Germany — it didn’t sell well at all in Germany — a lot of the Crumb fans were very disappointed because it wasn’t this outrageous takeoff. I had no idea how they would take it. And you know, people ask me if there’s been a lot of hostile reactions from religious people and I really haven’t gotten much of that. I got invited recently to come to the San Diego Comic Con. There’s some Christian comic fans that have a conference every year and discuss, like, spiritual aspects of comics. And they wanted to invite me, they wanted to have a panel about Genesis. And the guy that wrote to me, his name is Buzz Dixon. He said that not all Christians are happy with my version of Genesis. And I wrote back to him, I said, “I’m very curious, what do they object to?” I have no idea what they object to. I’m just doing a straight illustration job there. I’m curious to see what he’ll write back.”

In the introduction, he says “if my visual, literal approach offends or outrages some readers, which seems inevitable considering that the text is revered by many people . . . my defense is that [I had] no intention to ridicule . . .”

If he wanted to ridicule or intentionally offend, he could easliy have done a very different version.

“But getting basic facts wrong about Crumb’s past work, the book itself, or the cultural context in which it might be read and using them against Crumb is a mystery to me.”

That’s the thing with comments threads! It’s more like a conversation than a formal essay, so people tend to make mistakes, just as they would if you were chatting with them.

It’s also worth noting that people who don’t really care for a work are more likely to make mistakes about it. If you don’t like something, you tend not to care about it, and so don’t learn as much about it as a fan would. If you cut the conversation to include only folks who know a lot about the subject, you end up overwhelmingly talking to people who are enthusiasts. If you lower the bar for entrance, you will of course get some more factual errors, but you’ll also get different perspectives. The tradeoff seems worth it to me — though obviously some folks will disagree.

Your point about Crumb, for instance, does in fact indicate that I was wrong about his sense of the book’s controversialness. So mea culpa! And thank you for the info. Crumb does actually seem to be contradicting Alan’s sense that he created the book as some sort of quiet defiance/undercutting of Christian authority. At least in this quote he’s claiming a “straight illustration job”, which in context seems to mean that he’s avoiding any sort of ideological content. Though of course the artist’s words about this sort of thing shouldn’t necessarily be taken as gospel (as it were).

I’ve made plenty of mistakes, too, so I am sympathetic to this problem.

“If you don’t like something, you tend not to care about it.”

This may be true, but I often find that people seem to care the most, or react the most strongly, to things they dislike.

I don’t know about that. If you look on Amazon, you’ll see that people overwhelmingly tend to write about movies or books they like…unless something is especially controversial, in which case you’ll get more of a back and forth.

Still…it’s true that people do care about things they dislike. I guess it might have been better to say they don’t tend to investigate them deeply. If you watch an episode of Star Trek and hate it, you’re not likely to then go out and watch all possible episodes, read the novelizations, see the movies, etc.

Ken P.–

I didn’t write that there wasn’t controversy over The Da Vinci Code, just that it was quite muted compared to earlier ones. The controversy was certainly nothing comparable to what Godard’s Je vous salue, Marie, Serrano’s Piss Christ, or Scorsese’s The Last Temptation of Christ faced. It certainly didn’t define the public reputation of the novel or the film.

RSM wrote, “Attacking adaptations for insufficient fidelity to the original is a fairly recent phenomenon, one that can probably be traced to the rise of mass-media reviewing. Pauline Kael surmised in her review of Stanley Kubrick’s film adaptation of Lolita that much of it is likely due to a compulsion on the part of reviewers to create a pretense of erudition.”

I was thinking of the response we see in popular culture from the following of a book, and contrasting that to the response we’ve seen from people who are highly invested in this one; but I explain that initial contrast by putting it in the context of the history of the Bible, which has been treated in a selective, interpretive way right from its formation. In other words, I agree with you that it’s recent.

“Why is a comprehensive illumination of a work a significant accomplishment in and of itself? How many notable works have received a treatment of this sort, and do we really feel the lack with those that haven’t? Honestly, how often have we felt the lack with those that have? Crumb seems to think that next to no one knows Genesis except from adaptations, and that is definitely not the case.”

I explain the utility and interest of this adaptation in depth in my essay, and I look forward to hearing what you think.

“Crumb’s concern about a hostile response from religious fundamentalists is either misguided or a red herring…”

Crumb’s concern has no bearing on my argument; he was only explaining he could defend himself to people who take the Bible literally by saying he did too. If you’re responding to me at all, I described religious fundamentalists as “a major cultural force that would be foolish to ignore” in order to set up a contrast with a point in the comment I quote right after: “…I would suspect that very few, if any, clergy believe in the stories as literal, historical facts.” I find the idea that nobody takes it literally anyway to be an odd criticism of the book- so?- but I was making the point that people absolutely do, and I wonder how he managed not to notice.

For those who take umbrage at the content of Genesis, I highly recommend this illuminating commentary by Robert Sacks:

http://www.scribd.com/doc/27037688/Robert-Sacks-A-Commentary-on-the-Book-of-Genesis