Dominique Goblet’s and Nikita Fossoul’s Chronographie (Chronograph)

Some of you monolinguists may ask yourselves why do I bother to write at the HU about foreign books written in a foreign language (?)… There are a variety of reasons which explain why a columnist chooses his or her topics. Being a foreigner myself (and someone who manages to, at least, understand Latin languages) I have access to many books that aren’t available in North America. In this day and age though you’re just a few clicks way from these great comics (I’m old school, so, don’t expect me to say “graphic novels” very often).

My last post was about a scriptwriter who wrote in Spanish. His comics are a bit verbose (this isn’t a negative criticism: as I said elsewhere: I prefer great words to mediocre images and vice-versa, of course), not to mention completely out of print, but my other stumblings were wordless or almost wordless. (Unfortunately that’s not what happens with the links below: they mostly lead to not so silent French and Belgian sites.)

When I say “almost” I’m not implying that the words don’t count (contrariwise to a somewhat goofy comment that I wrote answering to another comment by Noah who “accused” me of just writing about European art comics). For instance, I didn’t mention in my first post that Pierre Duba wrote a few phrases in Racines about identity and quoted Norwegian writer Tarjei Vesaas. (I thank my friend Pedro Moura who linked Racines to another central book in the ideal comics canon: The Cage by Martin Vaughn-James; maybe I’ll come back to Duba one of these days; I have to, I’m afraid!…)

I wrote about Héctor Germán Oesterheld because I think that he is the best comics writer that ever existed (yes, better than Alan Moore) and the world needs to know more about him. Being an Argentinian he’s at a disadvantage (like everyone else that worked or works in comics outside of the holy trinity: Japan, U.S.A., France-Belgium). This applies even to countries with fairly important traditions in the field like Spain and Italy…

My other posts just mean that a comics avant-garde scene (Bart Beaty calls it a postmodern modernism – 2007) truly exists in Europe (this is an idea that goes back to Jan Baetens in his analysis of Autarcic Comix – 1995 – as reported by Paul Gravett in the link above). What interests me the most in comics are those borderline examples that push the limits of the form. Publishers like L’Association, Six pieds sous terre, Ego comme x, Frémok frequently publish, with the help of grants from the French and Belgian governments, highly experimental books that shatter to pieces our expectations of what a comic is supposed to be. Authors like Vincent Fortemps or Jochen Gerner are part of this unpopular (to quote Bart Beaty again) cultural movement.

I will stumble on some North American comic one of these days, I’m sure, but I don’t know exactly when… (North American comics authors respect comics’ mass art tradition too much for my taste. They are afraid of being called pretentious or elitists if they forget goofy caricatures, I suppose; maybe they should embrace Milton Caniff’s, Hal Foster’ s, Alex Raymond’s tradition instead to tell contemporary adult stories? Are the technical skills a problem though? Sadly, I suppose so… those giantly talented graphic artists are hard to match.)

Dominique Goblet is also part of that nineties’ European comics revolution that I mentioned above (she’s a Belgian). Nikita Fossoul is her daughter.

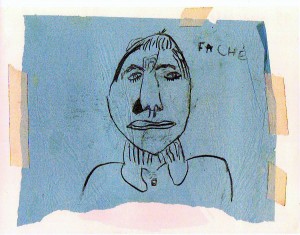

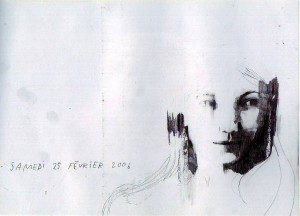

In Chronographie (another quasi-wordless book) they publish ten years of their more or less biweekly portraits of each other (Fossoul was seven years old when they began and Goblet was thirty one). Words are few and far between, but when they appear they add important meanings, not as an anchor in a Barthesian sense, but as time and context info and as emotional descriptors. It’s mostly Nikita who uses the latter saying thinks like: “Faché[e]” – “Pissed off.” Being in a powerless situation children need to pay attention to the adults’ moods. This doesn’t necessarily mean that Dominique was pissed off at the time though: it may simply mean that she appears to be pissed off and Nikita noticed this after doing the drawing (see below). (Curiously enough the words gradually disappear from Nikita’s portraits. I’m sure that there’s a paper here somewhere.)

Confronted with these kinds of books this television show host asked: “Can we still talk about comics?” I would answer definitely yes, but I hardly count… My answer is in accordance with my expansion of the comics field to include things from the distant or recent past (said expansion may be seen as an anachronism and a decontextualization). What’s new in this case is that these authors really are comics artists. L’Association (Chronography‘s publisher) is a comics publishing house (whose publisher Jean-Christophe Menu, as been one of the most vocal actors in the comics field to defend that really there is a comics avant-garde). If Frans Masereel never thought about it, I’m sure (I include him in comics history without his permission), they, on the other hand, want to do comics in a contemporary high culture context. As Dominique Goblet put it, answering the question:

We are at the crossroads between the visual arts and comics. The link that unites all this is a passion to tell stories.

(I would replace “tell stories” for “do sequences” because many things in, for instance, the Fort Thunder style shatters the narrative. On the other hand I suppose that it is defensible to say that two images put together, no matter what they represent, do tell a story of sorts… Also: the visual arts always have been a part of comics, so, I don’t see where the crossroad is. What Dominique Goblet says is understandable though: the visual arts have an important history of experimentation and comics don’t.)

In almost every session Goblet and Fossoul chose the same technique, the same composition solutions, explored the same particular aspects; they even shared model poses sometimes (see below). This coherence can only mean that Dominique Goblet was the art teacher and Nikita Fossoul was the student.

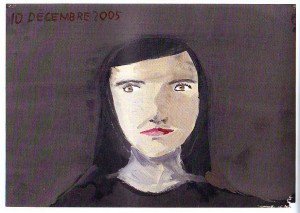

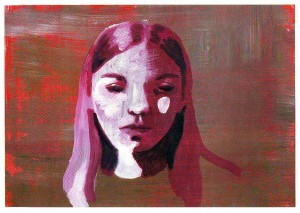

The book begins with graphite and black colored pencil line drawings. It continues exploring washes, pastels, collages, acrylic paint. The supports are all kinds of paper (old papers, drawing papers, etc… two of the drawings seem to have been done on some sort of synthetic board).

The problem of resemblance is at the center of the portrait genre. If Dominique Goblet solves this problem easily Nikita Fossoul doesn’t even address it. As she put it in the book’s postface (in both French and English, by the way):

So I drew what I sensed (almost) more than what I saw: a mood, a special complicity… Thanks to this lack of interest in strict likeness, I too could let go and no longer be afraid of ‘going wrong[,]’ and that is how I dared to carry on.

As she also says drawing was a game at first, but an evolution can easily be traced in her drawing skills. As for Dominique Goblet she draws in a contemporary sketchy (sometimes fragmented) style, but she never destroys her model’s face. She obscures it sometimes because she has a real interest in shadows and light (great vehicles to convey mood). Sometimes she just did beautiful simple drawings like the two below.

Ten years is a long time in a person’s life and Chronographie is about the passing of time, but what story do these faces tell us? When she began this project Dominique Goblet wanted to explore a mother / daughter relationship:

I have always wondered about what is called ‘maternal instinct[.]’ To be honest, I have never fundamentally understood what it could mean.

In any case, to my great regret I have never been sure of anything that obvious. I don’t know if I resemble those mothers who talk about unconditional love, instinct, the need to unreservedly protect.

One more time we reach the conclusion that philosophy, science, the arts start with the same impulse: the will to explore, the will to know beyond all clichés and common sense. A book depicting saccharine moments between a mother and a daughter would be a kitschy thing indeed. But that’s not what Chronographie is: there are moments of laughter, there are moments of bliss and there are moments of sadness. Life is a lot more complex and interesting than any pop myth (Dominique Goblet again):

Many things were said without words. The sequential work is carrying on, in a way, very slowly. What is told here traverses the prism of an imperceptible movement. The years spent together…

The essential is told, we have given more of ourselves than any memory would have done. This is no longer about details, let alone anecdotes.

The myth of the mother-daughter bond appears in another form: a silent tale.

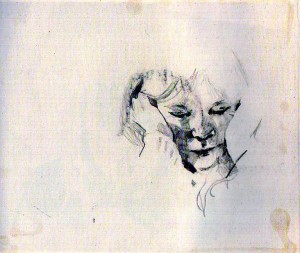

Imagining myself as a devil’s advocate I could say that Nikita Fossoul’s drawings are amateurish and Dominique Goblet’s drawings are sometimes great, sometimes not so great. All that is true, but is it really important? What matters is the inquisitiveness, the patience, the bond between mother, daughter, and the readers… life being lived and shared (that’s what real art is all about)… those rare moments in which we receive our rewards and get some answers… That’s why I finish this post with the only portrait in the book in which a young artist (she was twelve years old) captured her mother’s likeness, without even trying… It’s no wonder that she saw her with a pair of worried, slightly sad, eyes the size of the world… her world…

I don’t think you need to justify writing about non-English/non-North American works. There’s plenty of that to go around. I’d rather see you writing about these often unfamiliar works.

I’ve seen a few reviews/posts on this book, but yours is the first, oddly enough, to show some of the images. Still not sure it’s something I want to go to the trouble of getting (I’ve still got Goblet’s Faire Semblant C’est Mentir to finish digesting), but I think your make a good case for the book.

I love that fourth image. It kind of looks like an aged (water damaged, age spots) image by Rembrandt.

And thanks for that link to Goblet’s site. Hadn’t seen it before. The notebook selections have some really lovely pages in them: http://www.dominique-goblet.be/bande-dessinee.html

Oh sure, make fun of the monoglots why don’t you.

“life being lived and shared (that’s what real art is all about)”

It’s interesting that in praising the avant garde, you’re putting forward a view of art that’s very humanist, and not really avant garde at all as far as I can see. The dadaists wouldn’t agree with that formulation I don’t think, for example….

I’m pretty interested in the idea of comics as a time-lapse sequence rather than as a narrative sequence, though. Not sure this will be of that much interest, but my (semi-) collaborative art project with my son has some similarities with Gobblet and Fossoul’s book, I think. Change in technique as measure of passing time is something I was thinking about while working on it anyway, whether successfully or otherwise….

Noah, those drawings are pretty awesome (extra points for the D&D appropriation). They’d make a great minicomic/zine.

Up with articles in English about comics in French! (Now I need to go read the post: I started with the comments LOL.)

Really great drawings, Noah.

this is one of those books that i find great without even having read it (maybe in a few months, when it gets around to montreal… & even then, i might just wait for my trip to angoulême so i get it for a fair price). anyhow…

regarding the “story” vs “sequence” aspect… it’s a difficult question as, as you mention it, there is a potential story in every sequence; but conversely, even in the most obviously “story”-esque comic, the story is still something the reader rebuilds mentally out of whatever information is on the page (which is why, in some, maybe all, cases, we don’t read the same “story” the author actually intended for us to read).

the problem with the “sequence” is that it turns comics into a one-dimensional medium; whereas the whole space of the page is readable, & there is not just one direction to that reading. at least that’s the essence of groensteen’s theory (in système de la bande dessinée, which i think was translated as system of comics), which i find globally accurate. & that’s why he talks about the “système spatio-topique” which is meant to incorporate the whole experience of “reading comics”. one advantage of this, i find, is that it offers a better critical toolbox for many avant-garde works, which eschew a lot of the traditional “storytelling” elements, & where even “sequence” is just one way to read among others. not just that, it offers new possible readings of “classic” material which us critics are too used to view from the sole viewpoints of “the story” & “the art”.

anyway, just a few thoughts thrown around on this sunday morning (oops, noon actually). i’ve stumbled upon those problems recently (trying to write a commentary on groensteen’s système) so really i’m just thinking out loud here.

Domingos,

Maybe I’m hardwired to hate stuff like this, but you say:

A book about that unconditional love between a mother and a daughter would be a kitschy thing indeed. But that’s not what Chronographie is: there are moments of laughter, there are moments of bliss and there are moments of sadness. Life is a lot more complex and interesting than any pop myth

Isn’t the point behind this book a mother-daughter relationship? The unconditional love is always despite the hardship, the sadness, etc.. That’s what makes it “unconditional.” From what I can tell, this is supposed to be interesting to others (i.e., not the artist) because of who’s doing it. That’s also why it’s comics: a comics publisher is publishing a comics artist and her daughter (the institutional theory, which is good enough for me, but i don’t much care about how people define ‘comics’). You point to a lot of questions posed, but I’m not seeing any answers. This just seems to be yet another autobio “look at me” kind of work. I suspect there’s a “myth” in there, too.

As for the formalist justification of the time between “panels” actually reflecting real time, I’m reminded of those instances of acting where the actor who’s supposed to be “playing” tired or fat or drug-addled actually doesn’t sleep or gains weight or does a lot of drugs. Does it ultimately matter to the finished product? Not so much, as long as it works. On the other hand, I’m probably more impressed with the actor’s ability who’s capable of making me think that he’s on drugs or whatever without actually being on drugs.

Derik:

Thanks for being interested. I know that I don’t need to justify myself. It was just a way to get things going…

Noah:

People may not believe this, but ultimately I have a low class taste. I’m really a hooded utilitarian because if on one hand I’m not very fond of mass art, on the other hand here’s what Pierre Bourdieu says about low class taste: “The submission to necessity […] inclines working-class people to a pragmatic, functionalist ‘aesthetic,’ refusing the gratuity and futility of formal exercises and every form of art for art’s sake […].”

This is a refusal both of the aristocratic escapist taste (seen in times of intense crisis like the Gothic period – in its international branch – or the Rococo period). This attitude also explains why low class adults view comics as silly and childish, not a culture for the masses that must be revindicated. If children’s comics are going to be legitimized someday it will be a feat achieved by bourgeois intellectuals, not by low class readers.

I don’t reject formal exercises per se though. I think that they are very important in the history of every art form. I just prefer that they have some substance (that’s what Matthias calls my propensity to naturalism).

I agree with you re. the Dadaists, but they also wanted to close the gap between art and life.

Ooops, a non sequitur: “This is a refusal both of the aristocratic escapist taste (seen in times of intense crisis like the Gothic period – in its international branch – or the Rococo period)” AND the escapism of mass art.

Charles, I haven’t read the whole book obviously, and as my comment to Domingos indicated, the sentimentality of it puts me off somewhat too. On the other hand…I think you get around a good bit of what I dislike about typical autobio stuff by making the book about a collaboration and a relationship. That is, it’s a lot less solipsistic if it’s a conversation than if it’s a monologue. I also find process interesting…and I think the statement it’s making about children’s art is a pretty valuable one (and a political one, actually.) And it’s also really technically proficient (even fetishizing technique) in a way that separates it from a lot of indie autobiographic work.

So in summary, while I see where you’re coming from and share some of your reservations, even so it seems to me that there are a lot of interesting things going on here.

Domingos, I really, really like the idea of Marxists as hooded utilitarians. That cracks me up. (I hope you don’t mind being called a Marxist. I know it’s a dirty word for many, and it’s not precisely where I’m coming from, but I think it’s an honorable intellectual tradition.)

Thanks for the kind words Derik and Caro. Derik, I did a zine with some of the drawings actually…may have some of them lying around somewhere….

David:

Those are not Gröensteen’s ideas. Gerard Genette was the first to talk about a linear reading and a tabular reading. If you ask any French or Belgian comics scholar they will immediately say that this was a discovery by Pierre-Fresnault Deruelle, but this this seems to me to be the result of Deruelle’s intellectual dishonesty.

What Gröensteen discovered was the concept of braiding. He also showed great concrete examples. That’s what I like the most in Gröensteen’s books and essays: his close readings.

Charles:

Are you kidding? How many mothers and daughters don’t even talk to each other? This is not Goblet’s and Fossoul’s case, so, I agree with you and I clearly need to revise that part.

I’m not particularly interested in finding answers where answers are impossible to find. That’s a huge waste of time. Any comics definition can’t be agreed upon by everyone, so, let’s leave it at that. I just stated a fact: comics artists published by comics publishers are seriously pushing the comics envelope.

As for “autobio” and myth, there’s not one, but two in the comics milieu: (1) it’s the truth (it’s really fiction because it is an interpretation of reality); (2) they’re better than fiction (they’re not: even if some genres are extremely limiting – e. g. the superheroes that I love to hate – a comic is just as good as the artist doing it).

As for the last part of your comment: do you know how difficult it is to fake children’s drawings?

Plus: what Noah said. In spite of Goblet being an accomplished artist (she’s one of my favorite comics artists really, check out her other books), I found myself wondering why did Fossoul’s portraits seem so frequently more interesting. I think that this happened because she was more intuitive. She didn’t have “a style” to worry about. This has nothing to do with an appreciation for any outsider art though…

Noah:

I don’t mind being called a Marxist, I do have some sympathy for the Situationist movement. Maybe that will be my next stumbling? It’s just a thought.

Domingos, I think you’re praise of Fossoul’s work is very much in the tradition of appreciating outsider art, actually. The idea that outsiders/children/the insane are able to get outside of tradition in interesting ways is certainly one way in which outsider artists are often discussed or appeciated.

I like a lot of outsider art, so I don’t see that as a problem per se…though there are obviously some problems with the enthusiasm for outsider art as well….

In the autobio as conversation vein, Goblet’s Fair Semblant C’est Mentir has two of its 4 chapters co-written with one of the other protagonists of the story, Goblet’s (ex, I think) boyfriend.

Domingos: Do you know which of Genette’s works discusses the linear/tabular reading? I don’t think I’ve come across that in the books of his I’ve read.

Noah: If you have any of those zines, I can paypal you some postage money. Or I can send you some minicomics in trade.

Trade is fine. Or, you know, I can just send them to you. I’ll email you when I see what I’ve got….

domingos: i’m actually going through all of genette’s books but like derik, i have to say i haven’t gotten to that linear/tabular part. (or i skimmed through it, who knows?) genette never talks about comics of course (which he has a hard time considering as literature, for the wrong reasons i think), so i suppose he was refering to something like “poetry as a graphic medium”?

but, you’re right anyway, groensteen didn’t invent the whole theory we’re talking about, but he did express it quite eloquently (as you mention). & so when i say it is “his” theory, what i mean is that he makes it his own, which i would argue is more relevant (for our purposes) than knowing whether he was the first human on the planet to think it up.

but then we’re veering off-topic, i suppose. which is my unfortunate general tendancy. sorry.

Noah:

The problem that I have with the appreciation of outsider art is that it robs the artist of his or her individuality. Outsider artists become part of a freak show.

Derik:

Cf. Genette, _Figures III_, 77: http://tinyurl.com/2vpmpja

Yes, that’s one of the (big) problems with outsider art, I agree.

Thanks for the cite, Domingos. I tracked down the English translation for the curious:

“…the comic strip…which, while making up a sequence of images and thus requiring a successive or diachronic reading, also lend themselves to, and even invite, a kind of global and synchronic look–or at least a look whose direction is no longer determined by the sequence of images.” (Narrative Discourse, 34)

derik: if you read genette in english, that’s from “Narrative Discourse: An Essay in Method”.

woops, too late. :) all right, here ends my contribution to this topic. see you all some other time.

This is just a quick note to say that I updated Charles’ quote. I also have to thank Clare Tufts (in _European Comic Art_ # 1, 47) for the Genette discovery.

Seymour chatman also uses comics for examples of structuralist narrative theory (a la Genette) in story and discourse.

Hi Domingos,

I think your devil’s advocate threw himself on the mercy of the court too quickly. I’ll try to be that advocate’s advocate — or maybe just be the devil.

You conclude:

I’m not sure why an appreciation of a “life being lived and shared” or the “patience” and “bond[ing]” involved in a project in any way disables criticism of the quality of the final work — much less shows that such an aesthetic critique “misses the point.”

It seems that the positive qualities you site (patience, feelings, and “a life shared”) speak, I suppose, to the concept behind the art, on the one hand, and to the emotional origins of the piece on the other.

Neither, it seems, have any impact on the quality of the execution.

In fact, a truly grumpy person could take issue with these twin attempts to unravel any strong aesthetic criticism. Both ultimately take one’s eyes off the work itself and ask you to focus instead on the mind and the heart of the artist.

They are also critical conversation stoppers.

For example, imagine I am your aforementioned devil’s advocate, and I say, “Gee these drawings are really not so good, falling as they do into predicable patterns and easy drawing-course solutions.”

If you disagree about the artistic quality of the pieces, you could point at the work, help me see why you find them so lively or powerful or well turned-out.

But if you say, “That criticism is beside the point; the value of this art — and any art — is about a life being lived and shared,” you leave me without recourse.

You create a situation where any art that emerges from a sharing of life as it is lived — from deep feeling or patience or emotional bonds — is immune to criticism. In addition, you transform my criticism into an attack, not on the work, but on the life, the sharing, and the feelings of the artists.

I have little to say about his particular work. I only know what you have shown me. But I wonder why I should find it any more interesting than those YouTube videos where people take pictures of themselves everyday for years (videos that I sometimes do find affecting, but not for reasons that answer much to aesthetics or to argument.

This, I fear, is the poison center inside much autobiographical art.

Hey Peter:

I don’t find much to disagree with in your comment. One aspect with which I blatantly disagree though is the last one, so, let’s get it out of the way.

I also find that You Tube video interesting (if you want to go to the root of these things go look for On Kawara’s work). These projects are appealing to me, but I like lots of conceptual art, so, you are right when you say that the concept behind the project is very important… Why then do I find the You Tube video poorer than Goblet’s and Kossoul’s project? The artist’s expression in the video is always the same. The drawings in the comic have variations in technique, aesthetic (from a 7 year old to a 17 year old you can imagine how Nikita’s drawing style has to change), but more importantly to me: they show changes in mood.

I agree with your point re. technical execution, but… How can we realistically demand two things: (1) Dominique Goblet’s drawings to be all equally great (one of my favorite artists, Gerhard Richter – hey!, I have to stumble on his monumental _Atlas_ one of these days! – said that “art happens;” I agree, even a genius like Picasso who produced lots and lots of all kinds of visual art did, as he put it, “false Picassos;” if an artist imposes a schedule on him/herself art may not happen sometimes…); (2) great technical skills from a 7 – 17 year old. As you see, the project itself limited the drawings’ technical greatness. The truth is that I’m more than fed up with the comics milieu’s technical fetishism. A few ideas are more than welcome to me. I consider aesthetic appreciations not as absolutes, but more like votes in a political sense. People just choose their side of the barricade. I choose intelligence and liveliness over technique any time…

Re. autobio, I think that the problem lies somewhere else and Japanese writers solved it. Here’s what I wrote on my blog: “Japanese writers distinguish two varieties in autobiography: one that deals with a public persona (jiden) and one that deals with more private affairs (watakuchi). Tsuge’s I-comics belong to the latter classification. As Chôkitsu Kurumatani stated […] “I-novels question the root of one self’s existence… this ominous and mysteriously unknown part that hides inside the ground of daily life.” (This is marvelously put and makes perfect sense to me: I always distinguished between Chester Brown, John Porcellino, Fabrice Neaud, and mostly all the others who did autobiography: the former had the courage to expose themselves doing I-comics, the others just dealt with daily life’s foam.).”

People taking snapshots of themselves every day for years is an entirely valid visual art project. It can be done well or not, but it’s definitely within visual art aesthetics as they’re currently constructed.

I in general have a lot of reservations about autobio comics, and I agree with you that life and/or sharing qua life and/or sharing is not an aesthetic argument in itself — but, at the same time, I think that art about sharing or a relationship can be interesting conceptually, technically, thematically, or for a host of other reasons. And on those grounds, while I’m not sure I’d love this if I saw the whole thing, there definitely are aspects of it that seem appealing and interesting and potentially moving.

I dunno…I just don’t want to go over to the other side and refuse to value any art that is personal or autobiographical. There’s a lot of good autobiographical art. I actually think it’s pretty valuable in itself to find a way to do autobiography that’s so different from the literal day-by-day hipster tedium of a lot of indie autobio. Moving to something more like those YouTube videos seems like a real step in the right direction.

I’ve gotten a little buried this week and am wondering if (in the interest of slow-rolling comments that will give me time to catch up) I could prompt Noah and Peter to a few more musings on the “hipster tedium” and “poisonous center” of autobiographical art.

My gut intuition is that the more indie the autobiography the more poisonous the center, but I can’t articulate right off why that would be…

I don’t know that I think that the more indie the worse it is. I really like Ariel Schrag, and she’s quite indie.

For me, there’s just a very literal minded approach to autobio that I find really problematic. Basically, there is a fair amount of autobio work that privileges honesty over concept or technique, and that presents “honesty” in terms of relating whatever happens in as mundane a fashion as possible and insisting that the very mundanity makes it profound. It’s probably Harvey Pekar’s fault in some sense (though he’s a better storyteller than many who followed in his shoes.) (Those people who have followed in his shoes include Jeff Brown, Gabrielle Bell, David Heatley, Ivan Brunetti, Julie Doucet…not that I hate everything by all (or actually any) of those creators, but they’ve all worked in that mode.)

It ties in, for me, with Crumb’s approach in Genesis actually — or with Spiegelman’s Maus (which, despite the jews-are-mice conceit and some pomo flourishes is really, really linear and deliberately dry in most respects.) It seems to me like a reaction against the fantastic elements of pulp comics too…as if restricting imagination is a way to get highbrow, or at least middle brow after the pulpy excesses of yore.

Anyway, Goblet’s project here seems very different than that. It obviously approaches the concept of self and autobiography in a accretive way — it puts spaces in the linear narrative, which opens up the way the comic works as well as the idea of a unitary self (both in the sense that the self changes over time and in the sense that this isn’t actually autobiography — none of the portraits are self-portraits.)

To me the problem with autobiographic work is often that the choice to do autobiography often seems to mean eschewing concept or thought in a lot of ways. I don’t think that has to be the case for autobiography at all…there are many great autobiographical works in virtually every medium.

It’s really funny that you put Harvey Pekar and Art Spiegelman in the same bag.

Do they hate each other or something?

Noah: I guess I was sort of haphazardly and without much thought defining “indie” as

Maybe that’s just hipster? You just use two adjectives “hipster” and “indie” that do seem to sweep up a good bit of this tendency, but I’m happy for a different adj for it. It’s just that the Profundity of the Mundane is common enough that it feels like a real cultural thing.

I agree the imagination is restricted but I don’t think it’s to “get highbrow” and I don’t think — I don’t have any idea really but it seems to me that the people who write those kinds of “indie, hipster” autobiographies wouldn’t say they were being unimaginative, would they? The Profundity of the Mundane doesn’t code as unimaginative, surely, to the people who dig it?

I also agree it’s not inherent to autobiography and I agree that it isn’t what’s going on in Goblet’s project: I’m really just trying to get at why there is a particular subgenre of autobiography that gives so much more attention to the Mundane than the conceptual. I guess I would like “The Illustrated History of the Hipster Mundane, with Theoretical Annotations,” please.

I think this approach is more characteristic of the indie-hipster subculture than it is characteristic of any particular subgenre of any particular art form. I see indie-hipsters really getting into the Mundane in prose too. But it’s a guess: I don’t know if it’s actually true, and even if it is I really can’t fathom WHY it is or how the hell we got there, let alone how we can get the hell out.

Well, I think of indie as at least somewhat related to mode of production I guess….

Hipster works okay I suppose. I’d say it’s partly the Beat’s fault. On the Road is probably a major touchstone. There’s probably a connection with punk rock too…though punk in music is often really weird and creative and not particularly mundane.

I’m sure they wouldn’t say they were unimaginative! But at least in comics I do think there’s an effort to get away from pulp.

And, of course, memoir is actually really popular. So I think that’s an incentive to write in that genre.

I kind of argue this out at tedious length here and here.

Noah:

Pekar was maybe the only critic to diss _Maus_ when it was published. Robert Fiore vs. Pekar over _Maus_, was one of the epic, already mythical feuds in the ol’ Journal.

That’s interesting. I see differences between them as well…but at least form my perspective there are a lot of similarities too.

I don’t want to derail an interesting conversation, but this is one of my pet peeves and I can’t let it pass:

Noah: “Schulz even admitted that Charlie Brown’s unrequited affection for the little red-haired girl had its basis in Schulz’s own romantic rejection at the hands of a red-headed woman named Donna Mae Johnson.”

Not to mention the girl with the red pink dress in Percy Crosby’s _Skippy_.

OK, sorry to get back on this topic after i had promised i wouldn’t but– are you gals (& guys) really using the words “indie” & “hipster” in a serious context? without scare quotes & all? damn, you’re hardcore.

now, my main take re: “mundane” autobiography, is that autobiography, at its core, needs to deal with questions of truth vs secret. on one hand, you have the impulse to say everything you want with bare honesty, on the other you will want to hide some things so as to not hurt people, not to mention keep yourself out of trouble (legal or otherwise).

hence: the “mundane” autobiography (neaud & menu call it “autobiographie de proximité” in l’éprouvette no 3) which solves this problem simply by keeping out of harm’s way at all occasions. nobody’s going to jump back at you because you described something that everybody already more or less knows. you just have to tell it in an interesting way, using the general tools of fiction. the litmus test for the reader here is: can i identify?

conversely, “honest” autobiography (notice the scare quotes?) sort of values content over style, as it is mainly concerned with telling true stories: the litmus test is: is it real? then again, no autobiography is ever truly “honest”, no matter how much it claims to be: things will be removed, added, modified, even just for the sake of narrative clarity.

obviously, these are extremes, most autobiographers will do something inbetween. the worst problem that can arise, for the reader, is when someone draws “mundane” material with an obviously “honest” conceit, i.e. pretending, through a story’s general discursive mode & aesthetic “stylelessness”, that what you’re reading is the “truth”, whereas all you see is banal observations. not that it’s wrong per se… it’s just that for the reader, you get the worst of both worlds, & i suspect this is precisely the cliché that irks so many people who dismiss “the autobio genre” outright (usually without being able to name specific examples).

& frankly, none of this has anything to do with “indie” actually. i don’t know for sure about the US, but in france (for example) you will find purely “mainstream” (whatever that means) comics dealing in a perfectly “mundane” setting. & on the other hand you get fabrice neaud.

at least that’s the big picture as i see it. feel free to argue!

Pingback: June 2011 banner by Dominique Goblet | The Comics Grid | The Grid