There’s a style of talking about the Christian God that you find in rural corners of the American South where there are Free Will Baptists and Pentecostal Holiness churches. Imbued with images and rich with metaphor, it’s also thickly oral, repetitious and rhythmic – reading transcripts of sermons aloud is like holding pebbles of words in your mouth:

I was voted in to pastor a church away down in southeast Alabama. I felt like I was drifting into a paradise opportunity to work for God, but really I was headed for the jaws of a vice on the Devil’s workbench. What I didn’t know what that the young people outvoted some of the old-time goatheads which was trying to bring in an older minister. They had future trouble up their sleeves…[they said] we are going to bring our minister to church and he is going to take the pulpit.

“When the other people at the church heard this, they were ready for a fight. One rough sinner-man came to me and said “I have a real sharp knife and I ate peas and cornbread in prison before and I can do it again. Don’t worry, no one is going to take your pulpit. My knife is sharp and I’ve been in trouble before.” So I woke up in a vice between a prospering church and a blood-shedding fight. I wanted to preserve peace, but that ain’t easy, because the Devil has got me in that vice time after time…Preachers think they got power just by preaching and that sinners will get saved. You can’t run sinners out of church. You have to run them into church and make it a soul-saving station for God.”

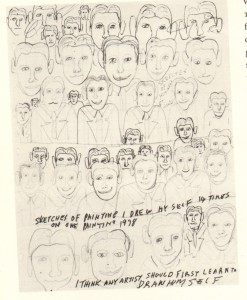

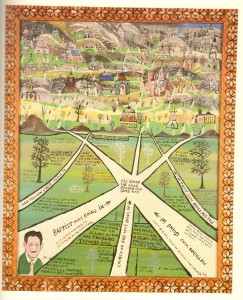

Howard Finster (who wrote and drew the above) was a particularly strong example of this way of talking about God. It was common, among people of his generation, in the Pentecostal sects of his part of the south, where the Holy Spirit gets a seat at the table and the church elders speak in tongues, but even there his imagination was more vivid than most.

His paintings, which I linked to briefly a few days ago, share the same sensibility as his sermons – a mixing up of images and metaphors from sacred and secular life, mixing that he thought was essential to his evangelical purpose.

In these places, deep in the rural South, where the nearest town of any size is hours away and the churches have had the same families in the same pews for 100 years, religion stops feeling like a choice, because culture is so saturated with faith it’s not something you believe, it’s just the way things are. “Ashes to ashes, dust to dust” isn’t just a phrase in a funeral: it describes that sense that everything in the world is made of the same stuff and that stuff is God: the trees and the fish and the people and the boards of your porch and the bricks of your church.

Howard Finster draws the psyche of that place.

It’s come up several times that asking R.Crumb to “have some imagination, damn it,” (in Genesis, at least) is somehow tied up with asking him to be more religious, or that seeing his imagination as falling short is somehow due to mistakenly looking for signs of belief. I think, though, that it does Howard Finster’s imagination a great disservice to attribute it to his faith. There are too many faithful people who don’t have it. I wish faith did automatically produce it: then we’d have more art like his.

============

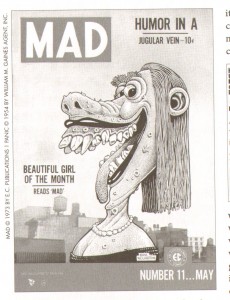

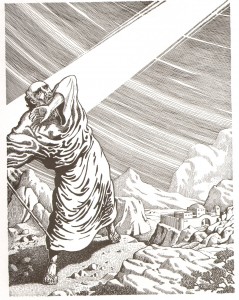

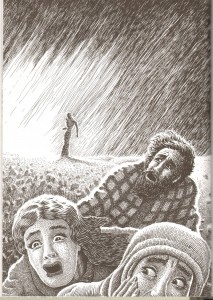

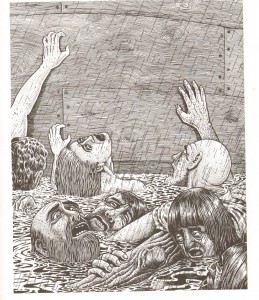

Cartoonist Basil Wolverton was also a believer when he began illustrating Bible stories and verses for evangelist Herbert Armstrong in the early 1950s. Wolverton had been drawing comics since 1925 and was drawing for Mad at the time he started illustrating the Bible. His cartoons influenced Crumb and other underground cartoonists – he drew grotesque, weird, exaggeratedly humourous characters that, despite his protestations about intent, were viewed as highly sexually suggestive.

His Biblical illustrations, unsurprisingly, are more straightforward and serious, although the exaggerated sensibility sneaks through. In the introduction to “The Wolverton Bible,” his son Monte observes:

Wolverton’s challenge was to portray the Biblical accounts accurately without tramautizing children too much. Yet from his background in comics, he understood that children actually enjoy a certain amount of violence (how it effects them is another topic.) In this way he was a pioneer for later comic artists, beginning in the 1970s, who would bring a more realistic interpretation to graphic depictions of the Bible…he never backed down from his position that the Old Testament needed to be depicted for what it was.

(Sound familiar?) Like Finster’s, Wolverton’s approach is consistent with the declamation style practiced in his church, but Wolverton’s church was very different. Monte Wolverton describes Herbert Armstrong’s preaching style as “newscaster-like” and “devoid of churchy language.” Although essentially a one-man-show when Wolverton first became involved, Armstrong’s church, called the Worldwide Church of God, had become extremely rule-bound and institutionalized by the end of the 1960s – members who disagreed with church teaching were “disfellowshipped.” (It was not a typical fundamentalist church, however, as it did not prevent drinking, dancing or other social activities.) Wolverton himself was a jovial, congenial and funny man who loved to entertain. His drawings reflect this mixed vantage point: the serious, “newscaster-like” declamation with a great appreciation for humanity and personality.

It seems obvious that Wolverton’s treatment of the Bible was more influential on Crumb than Finster’s, although I have no evidence that Crumb saw these Biblical drawings before beginning his work. Crumb’s Bible strikes me as very much the literal Evangelical Bible, though, so it wouldn’t surprise me if there was genealogy through this path.

What’s more difficult to account for, for me personally, is the greater aesthetic impact I feel from the Wolverton drawings, since they are in many respects so very similar to Crumb’s. In comparison, I think much of my dissatisfaction with Genesis does in fact come from two formal elements of the comic idiom: the grid, which provides a repetitive overarching composition even when the in-panel composition is varied, and the transformation of the prose text from its familiar, “native” graphic presentation in the columnar numbered pages of the Bible, into the comics idiom of captions and balloons. Text is, for all its abstraction, also a visual medium, and the flow and sound of the text in normal prose presentation is governed by different interactions than the ones in Crumb’s comics version.

My lack of appreciation for this – my sense that more is lost than is gained – is without doubt my limitation, not Crumb’s, and in this particular matter, an issue of personal aesthetic preference. But the comparison raises questions about the impact and effect of “sequential art”: I think because most people who read comics have an affinity for these elements of the idiom, they’re often accepted unquestioningly, without critical challenges or evaluation. A “nothing left out!” illustration job is a translation of sorts – normally the prose Bible is very aural; in Crumb’s book that aurality is replaced with the visual. The oft-described effect of “making the pictures narrate” is very palpable here – Crumb is without doubt successful at that effort – but to what end? Is it really just a “translation” into the comics “language”?

I think it may be — while Finster in particular can stand up against the more elite Biblical art that Suat drew on in his comparison and Wolverton’s approach is at least highly representative of his particular individual reading, Crumb’s is much less an individual reading than either. His very successful effort to humanize the Biblical characters resulted in a dehumanization of the experience overall. This perhaps shows us Alter’s error: it is not the concretization of images that marks the limit of the comics form at this moment in history, but instead the lack of imagination regarding the ways in which illustration can be fully literary without being tied relentlessly to sequence, grid, and narrative. Some experimental cartoonists are working to imagine new notions, but the far-more-common reliance on sequence to capture the spirit of literature – well, it only “captures” it, like a wild animal kept in a tiny cage.

Howard Finster described himself like this: “To do art like them fellas do in the books, it would take months. I’m a cartoonist. I don’t fool with details like that.” Without those details, an imagination like Finster’s makes all the difference.

============

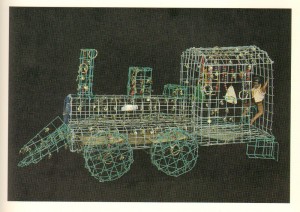

Images and quotations in this post are taken from: “Howard Finster, Man of Visions: the Life and Work of a Self-Taught Artist” by J.F. Turner (Knopf, 1989) and “The Wolverton Bible: The Old Testament and Book of Revelation through the Pen of Basil Wolverton,” Monte Wolverton, compiler (Fantagraphics, 2009).

The Finster is amazing…especially that train engine. What a weird and beautiful drawing.

I’m also more taken with the Wolverton than with the Crumb. He’s definitely much more aware of compositional effects — or uses them in a way I find more pleasing, anyway. The flood victims is especially dramatic — and again the use of composition actually makes it seem much more tactile than anything in Crumb (though Crumb’s figures are probably better drawn in some sense.) (The God speaks to Noah one is still pretty kitchy, though.)

There are ways to take advantage of the repetitive nature of the grid, or to do comics without using the grid, or to vary it. Crumb has done some of that in various places in the past, but he seems to have seen “literal” in this case as not just doing every word, but as really not making much effort to shape the material in any sense. Which seems like a weakness to me.

The grid always gives me grief, kind of. But never so much as Gridded Genesis.

I think Wolverton drew that Noah panel pretty early — it’s way kitsch, but it was drawn in the ’50s for basically a glorified church newsletter, so I don’t know that we should be surprised. I picked the images that would be comparisons with Crumb, but the Genesis ones are actually some of the least interesting: Exodus is extraordinary, as is Judges, and of course Revelation was made for artists. There are also some random things: a really nice set of drawings of the animals you can eat and the animals you can’t eat. I had no idea that Moose and grasshoppers were kosher…

I think that train is actually a sculpture made out of wire…at least, if you mean the wire train as opposed to the Devil’s Vice…

Aha! That makes sense that it’s a sculpture.

Nice piece Caro. The Finster art is pretty cool and I enjoy Wolverton’s spaghetti-and-meatballs cartooning given the apocalyptic inflection a lot! Wolverton, incidentally, was an important source of inspiration for Crumb in his earlier years, although I don’t know whether looked at the bible illustrations while doing Genesis.

Anyway, I think that you’re focusing on secondary elements here. Crumb uses a grid because he’s doing *comics*, not single-panel illustration — you can of course argue that the latter would have been a more effective choice, but I’m not sure that the faults you find with Crumb necessarily lie in his choice of page breakdown, as much as it does, as you say, his lack of imagination in his visualization of the text in the individual panels. He’s always been very traditional in this respect, sticking to a fairly rigid grid-like system and only rarely going for spectacular variations in page layout, and he’s achieved a lot of great things that way, to my mind.

Whether Genesis is one of them is of course what we’re debating, and it seems that Crumb’s choice of grid is only secondary to your argument about his lack of imagination.

But couldn’t the grid be part of the lack of imagination? I think it often is; I know for myself the unvarying layout in a lot of American comics is a real turnoff.

It could, but my sense from reading Caro’s, yours, and other people’s objections here, is that it is really secondary to what Crumb is putting in the panels. And as I wrote, I think Crumb has achieved plenty with a traditional grid in the past.

Crumb is not going for the dramatic histrionics of Wolverton, nor for the more internal, symbolic effect Finster achieves — he’s trying to illustrate the *entire* text of Genesis, something to which the comics form, with its propensity for juxtaposition of many small pictures, is arguably well suited for. It would be hard to do convincingly in those other formats.

I mean, for me, it’s really both. As Domingos says, form and content isn’t that separable. Part of what he’s putting in the panels is his decision to not do much with layout.

I don’t think it would be hard for Finster to do the entire text of genesis in a convincing way, if that’s what he wanted to do. There’d probably be more full page spreads with the text placed around the images, rather than juxtapositions of small panels. But would that be a loss?

As an example of how layout is content; I think the covers of Crumb’s Genesis are really wretched. There’s his usual knee-jerk evocation of old comics cover layouts, which to me in this context seems incredibly rote and simple-minded. Why do that except that it’s what he always does? It’s sort of semi-ironic, I guess, but it really seems more nostalgic; feeding the Bible into his own retro nostalgia not even for comics of the past, but for his own atrophied tropes.

Ah well…hopefully you will explain to me the error of my ways when you post tomorrow!

Hey Matthias: I’m hesitant to say that comics has to be on a grid: is “W the Whore Makes Her Tracks” not a comic? ‘Cause the illustrations are all single page. It seems to me it’s both single-panel illustrations and comics. But perhaps my nomenclature is off…

Here in particular, I was just trying to account for the fact that the strength of my “don’t like this” aesthetic response to Genesis doesn’t actually correspond to problems I have with the art in the panels. I don’t love the art, anymore than I love Wolverton’s. But I like Wolverton’s better, despite the similarities — and I think that has to do with it not being on the grid.

I don’t necessarily disagree with either you or Noah about what that means: I definitely think using a grid (now) shows a lack of imagination: but I agree entirely that it’s a choice tied into the influence of comics past.

I can certainly see that if I really loved what was in the panels I could more easily forgive the grid, so yes, it is secondary in that sense. But for me personally, it’s also more primary: because the grid is rigid to begin with, overcoming its limitations demands that extra imagination. Once the grid is there, I suppose, the bar is even higher, because as Noah points out, he made this decision not to do much with layout, and then made ANOTHER decision not to do much with imagery inside the layout. That makes it just about comics history — that’s why it seems like a translation into the comics language. I don’t disagree that the comics form is well suited for translation into the comics form, but it seems more tautological to me than to you, more “for its own sake.” Illustrating every line of something — is that really more than a “translation into pictures”?

Which boils down to my just very much not being the target audience for this book: in many ways it’s built around indulging an affection for the comics form, which I’m actually fairly resistant to in all but it’s most imaginative instances…that’s what I was getting to at the end. If you don’t just love comics, what is there for you to love in Crumb’s book?

Oh, if anybody at Fantagraphics is paying attention, maybe someone who was involved with the Wolverton Bible book might know how accessible these drawings were prior to their releasing the edition I have. The Fanta Wolverton book came out in 2009, so obviously Crumb didn’t see that version of it while working on his…

I think the grid approach definitely hurts the book as a reading experience. My big issue with Jeet Heer’s argument that the book should be read in the same manner with which scripture is traditionally treated is that Crumb’s page designs don’t promote that approach. The page structures demand that one read it as a traditional comic, and the rhythms are just one thud after another.

There’s definitely some conservatism going on with Crumb’s approach, and I think the covers are a good example of that, Noah. It has its problems, and I may well talk about how I perceive them tomorrow.

I further agree that form and content aren’t really separable — it’s one of the points I’ve been making since I started posting here — but it just doesn’t seem to me the main problem in this case. In fact, I actually think the page breakdowns help Crumb’s project: he wants to illustrate everything in the text and he was an interpretation that appears ‘neutral’ and doesn’t call too much attention to himself, in part because he’s regarding this as illustration in an instructional sense, I believe. And it functions very well that way — I noticed many things about Genesis that I hadn’t thought about before, precisely *because* of the form he had chosen: comics are great at elucidating things.

Of course, his intepretation is nevertheless very much him and combines his preference for comicky tropes with his talent for realist suggestion. Not an entirely unproblematic approach, but an interesting one and one I think many of the commentators here haven’t given due consideration. I’ll write about that some more tomorrow, but suffice it to say that I disagree quite fundamentally with the argument that Crumb ‘hasn’t done much’ with his imagery.

Also, don’t know whether this applies here, but one often sees in comics criticism this notion that if only that artist created more exciting page layouts, everything would be hunky-dory. Imaginative page layouts have their place (Crumb did some great ones in the 60s, for example), but more often than not they cause both aesthetic and semantic problems, especially when they’re not, as one often sees, well thought out in relation to the material. In the present case, I think the fairly traditional grid helps the reading, making it more understandable, all the while supporting the aesthetic project in that it mirrors the additive, at times recitative, structure of the narration of the Old Testament.

Caro, the notion of what a comic is, is clearly not fixed and is experiencing healthy expansion these days. I would absolutely agree that most of Feuchtenberger’s work is comics, for what that’s worth (I’m actually not that interested in definitions) — my point was merely that Crumb is attempting something quite different from what Finster and Wolverton are doing, and that the results as a result are quite different.

Well, I have various problems with that I think…but I’ll stop poking you and wait till your piece tomorrow maybe to go into it more!

Hey Matthias: I absolutely agree with you that the page layouts are essential to Crumb’s project and that it would be difficult to do what he set out to do without them – insofar as there is a “critique” in this it’s about how much his project is tied to the comics form. I think the advantages of the comics form are the advantages of his project — and the limitations of the comics form are the limitations of his project. The “neutrality” in this case shifts the perspective of the work itself from that of the artist to that of the form.

When you say this

I think you overestimate the “universality” of the comics form. I understand that what you mean by “neutral” is that he isn’t asserting his own imagination onto the text, and I agree. But there is absolutely nothing neutral about this book to me — because it’s a comic. That right there is not neutral.

Prose is the neutral ground to me; it is far and away the most efficient and effective way for me to take in information. The point I’m trying to make with the “translation” metaphor is that: the “neutral ground” is not a universal – it’s subjective and based on the commitments the reader brings to the work.

For the record, I hated Classics Illustrated as a child, too. :) I had these abridged simplified prose versions of grown-up books and lots of grown-up and entirely age-inappropriate prose books, and I (oddly) really loved Gauguin starting from the age of 4, and I loved illustrated children’s books (i.e., not comics) but that grid has bothered me since I could read! There’s no such thing as fully “neutral” ground…

Matthias, could you talk a bit more about this sometime, please: “…more often than not [imaginative page layouts] cause both aesthetic and semantic problems”? I’m not disputing you — I just haven’t read enough comics to encounter these problems and am curious what they are…

Oh, one more thing, Matthias! You say this:

I don’t know how carefully you’d read Genesis before …what I need to be convinced of, in order to appreciate the value of Crumb’s book as something other than a “translation,” is that the rendition would show Robert Alter things about Genesis that he hadn’t thought of before…

Caro, in re the imaginative page layout causing problems; if you look at mainstream comics, they often try to get somewhat tricky with page layout (inspired by manga) and end up with adifficult to follow mess. Manga can also be tricky to follow at times — though they’re often going for poetry rather than prose there.

Overall, I’d rather see folks try something hard and fail than just plod along. Even the worst mainstream dreck, hideous as it is, is better than Jeff Brown. But, obviously, mileage differs.

I think that most of the Wolverton illustrations are from the “Plain Truth” newsletter, which I just don’t know much about. It was off of my radar; I don’t know if it’s one of those things that “everyone” knows of (like, say, the “Watchtower”) or if it’s distribution was limited to within the faith.

I do know that a display of “Plain Truth” appears in Jonathan Demme’s “Something Wild” in the convenience store that Ray Liotta robs. So there’s that.

I’d seen examples of Wolverton’s Bible illustrations over the years in the Comics Journal and other places. I think Wolverton’s fans had learned of them and sought them out, traded them, wrote about them, etc. And they were often cited as a facet of Wolverton’s artistic persona. So I’m pretty sure that Crumb saw at least some of them.

Hey Chris — that’s a pretty convincing argument that Crumb had seen them. “Plain Truth” was off my radar too, but if even a few were reprinted in TCJ that’s pretty “mainstream” for the subculture. Wonder how they got into Demme’s convenience store LOL?!

Matthias, do you disagree with Noah’s implication that doing comics without the grid is harder than doing comics with it? The grid seems to me to be functioning similarly to the traditional plot arcs (like the 5-act Shakespearean play structure) in narrative prose fiction — as a conventional, static framework that a creator can either work entirely within or transcend in various ways…

Yeah, Caro, as Noah says, “imaginative” page layout has plagued superhero comics since Neal Adams’ innovations of the late 60s. The problem with that kind of thing is that it’s often there merely to look good, rather than for any good reason relating to the story or other content of the comics.

A pretty good, and rather successful of this recent example of this tradition is the work of J.H. Williams III, who did really impressive work with Alan Moore on Promethea, a series on which the two of them almost seemed to be competing about who could come up with the most inventive ideas, all to the benefit of the material. Williams has since worked with a number of other writers and has consistently outdone them, dressing mostly pedestrian plots to a point where it becomes mostly excess. Rather beautiful excess, but not really great comics. Jog had a great appreciation of these comics up last year.

And as Noah says, similar problems abound in manga, but of course it can be a worthwhile approach when done well.

As for Crumb’s ‘neutrality’ in Genesis, it’s only apparent. Of course the work isn’t neutral, he has merely made certain choices that makes it appear so — keeping the entirety of the text in there, sticking largely to the descriptions given in the text, and doing very little that could be construed as flashy or imposing. But his illustrations are clearly interpretative, and quite potently so, so no, it’s not neutral.

I don’t claim that the comics form is universal or neutral, and I’m puzzled you would say that prose is. What I’m talking about, however, is the way comics lend themselves to explication and elucidation of certain complex procedures or condensations of information: there’s a reason you find a little comic explaining what do do in case of an emergency in the pocket in front of you, when you sit down in a passenger airplane, or what is essentially comics, explaining assembly and use, accompanies many household gadgets when you buy them. Try doing that as effectively in prose.

In a sense, this is partly what Crumb’s Genesis did for me: in elucidated passages that had otherwise seemed obscure to me, made me notice things I’d glossed over in my previous readings of the text, or even in looking at other depictions of the stories — by making them concrete and visible on the page. Initially, this had nothing to do with intellectual appreciation, although it turned into that, because it made me consider what some of these things meant.

Obviously, somebody like Alter, who is intimately familiar with the text, might not have that experience to the same extent, but he did seem to show appreciation for certain of Crumb’s choices in his review: Lot’s daughters, the death of Onan, the introduction of Joseph’s interpreter before he is mentioned in the text, Pharaoh’s dreams, etc. I of course don’t know whether any of these things made Alter see the passages in a different light, but I wouldn’t be surprised if they did.

In this sense, it is very much in the Classics Illustrated tradition, but done much more competently than any of those that I’ve read, and as Alan pointed out, published along with the entirety of the source text.

Hmm. You grant prose a special status of neutrality, and, coincidentally, it’s the medium that you as writer work in. We call this “prose exceptionalism”. Numerous studies have shown that prose is often not the best way to transmit certain kinds of information. You may find such studies helpful.

Caro said she found prose the most amenable *for her*. Not that it was transcendentally exceptionally neutral, but that it *could be* the default for some.

The idea that you could do a study to determine the best way to transmit information is pseudo-scientific nonsense, precisely because information transmission is extremely culture bound, as well as individual.

I’m not saying that prose is neutral: read again. I’m saying that prose is neutral to me — and that comics is more neutral to you, because you are more comfortable with comics. My sense of the neutral ground is no less subjective than your sense of the neutral ground…NEITHER is neutral.

Or we can come into this from a different direction: what are the things in Genesis that really need comics to elucidate them, as opposed to just stand-alone pictures like Wolverton’s?

The root question for me being specifically — what is gained in translating Genesis from prose to comics? Because what is gained, given Crumb’s effort at neutrality, will likely be something not “of the artist” but “of the form.”

Is that clearer?

Matthias, when you say “comics lend themselves to explication and elucidation of certain complex procedures or condensations of information…try doing that as effectively in prose” that’s a claim that they are universally better than prose for those purposes.

But they’re not. My husband cannot read Ikea instructions AT ALL because they are all pictures. He is an almost-completely abstract thinker, extremely good at higher abstract math (and at reading sophisticated prose fiction), and the concretization of the process confuses him terribly. Neurochemistry was easy for him; neuroanatomy gave him fits. Pictures are not neutral or universal: as Noah says, we just live in a very concrete, graphic culture.

The studies that Writer refers to measure efficiency for some given population: if you tested people with English degrees you’d likely get different outcomes, because you’d be controlling away from the cultural dominance of images. The shift in pedagogy away from prose, for example, in math textbooks, toward images corresponds to that increasing prevalence of image-based content in our culture: it’s not universal, and there will always be outliers whose neutral frame is different.

When I took chemistry in grad school, I would rewrite every image or graph into prose and have my teacher confirm my understanding. I got extremely good at translating between the two idioms, and going back and forth made for a much deeper understanding of the material.

The same may very well be true for Crumb’s book — but at this point the process of going between the two seems very facile, and the assumption underlying most of the criticism — that the translation into pictures makes them universally clearer and more elucidated, limits the value of that criticism.

That’s why I’m still not hearing anything to suggest Crumb’s work is other than a translation: from a work that is optimized for people whose neutral ground is prose and poetry, to a work optimized for those whose neutral ground is images.

My previous question about which bits need comics rather than just images like Wolverton’s, though, still stands — that’s what criticism needs to answer. If anybody can identify that I think it would be immensely helpful for appreciating Crumb’s work!

Oh, I wasn’t try to make any absolutist claim here; i realize that these things are, to a large extent, constructions (although I’m sure your husband, as a neurscientist, might be helpful in explaining which perhaps aren’t so easily explained in that way) — I was merely pointing to the *usefulness* to may people today of comics in certain contexts. We can agree, at least, that they function differently than prose right?

I think the differences, and advantages if you will, of sequential pictorial narrative over single illustrations, should be fairly clear: it allows you more easily to show the *change*, especially in over short stretches of time, because you can show action and reaction more easily. An example would be the development of the relationship between Abra(ha)m and God through their life-long interaction. That wouldn’t be as easy to convey in a series of single illustrations, lest that series turn into comics. (Of course prose does this equally well, in a different way.)

True enough, in the last paragraph — I wonder how long Genesis would be if the panels were blown up and displayed one-to-a-page, so that you still have the sequence, but not the grid? (Just a thought experiment, not a suggestion…) Maybe I should have asked the question “what does the comics idiom allow Crumb to do that he couldn’t accomplish by a mixture of prose and illustrations?” That is, what’s the benefit to showing that change in images, as opposed to showing it in prose and using punctuated images for the things that can’t be accomplished in prose? After all, the prose is still there in Crumb’s book, to Robert’s point…

We do, absolutely, agree that comics function differently from prose. And they function differently in a variety of ways, some of which are more exciting to me than others. Crumb just happened to pick the ones which aren’t exciting to me.

I don’t really mean it as a particularly harsh criticism that it’s a translation into the comic form — this book does not inspire disgust in me; it inspires boredom. It’s more — why would I read a French translation of an English book when I could just read the English? The reasons I can think of are that it was pedagogical, to get better at reading French, or because the French translator had done something to the English that was worth experiencing…

It may also help if I say that I don’t actually disagree with much of Alter’s review, including the points you cite. I felt as I made my choices for what to write about here that there was nothing I could add to that list, given that I didn’t feel an affinity with the book.

I just feel like in the conversations we’ve been having about it not enough attention has been paid to the question that begins the closing section of Alter’s review:

Alter’s the only person yet who has dealt with that question at a level that actually satisfies someone who is inclined to agree with him about the specific limitations of the images, and he comes down against the comic. Most of the defenses of Genesis start by presuming some sort of inherent or at least obvious value to visual depiction — either the “universality” in the comments above with regards to images superlative power of elucidation, or simply an affection for the comic form. Alter points out an inherent value of prose — it’s lack of concrete specificity — that comics interrupts, and that’s dismissed out of hand.

Comics criticism has done a very good job of addressing Crumb’s book on its own terms, but not a good job at all addressing the kind of criticism represented in Alter’s concluding section: there’s the knee-jerk insular “he doesn’t understand how comics works” (made more passionately in regards to Bloom’s scoffing review, which in my reading is intentionally dismissive and snobbish rather than stupid) but so far, for prose-centric people, that’s the only response comics criticism has come up with.

That is a critical failure. This book is positioned to be a tremendously influential cross-over text between the comics world and the literary world. So the limitations that literary people see here are worth taking seriously. Otherwise the impression is that comics can’t respond to them effectively.

It’s a cop-out to say that people who don’t like comics (like Bloom) or people who see limitations of comics in comparison with prose (like Alter) are missing obvious benefits or don’t understand comics (not that you’re saying that, but it’s been said about Bloom and it’s a general sense I have of how people here respond to those critiques). But it is entirely possible to understand comics very well and still not like them, and criticism should be able to speak to the merits of a work even in situations where the reader of the criticism is not predisposed to give the work the benefit of the doubt…

Oh, I don’t disagree, and I think Alter’s review is very commendable in that respect, amongst others (I didn’t vote for it for best piece of comics criticism 2009 because I hated it). I don’t agree with him entirely, but he certainly points to an interesting set of issues.

I do think, however, that you’re selling Crumb’s version short, when you call it a ‘translation’ — it’s clear to me that it’s an *interpretation*, a form of exegesis (even if not the kind Robert, Suat or Noah would have wished). That, to me, is the value of the project — it provides an interpretation of the text; it doesn’t just translate it, which — even if it were possible to do so between prose and comics — I agree would be pretty uninteresting.

I should note that when I brought up the usefulness of comics to elucidate certain things, it wasn’t a defense of the book as a work of art, merely an aspect of it that I find valuable.

Also, I don’t think you’re doing Alan’s piece justice when you talk about the critical failure of comics critics in relation to this book. I think he offers a very persuasive argument for the value of Crumb’s interpretation of the text, and one that in no way implicitly claims that images or comics are fundamentally superior to prose, which is what you seem to be suggesting that comics critics are doing. Jeet’s original review, though much shorter and less involved, also pointed to some interesting aspects of the book, by the way.

Of course, it’s hard for anyone taking that tack to satisfy you when you frame your demands like this:

“Alter’s the only person yet who has dealt with that question at a level that actually satisfies someone who is inclined to agree with him about the specific limitations of the images, and he comes down against the comic.”

This would imply, it seems to me, that only those who would argue that the images ultimately fail the text would satisfy you, because your prejudice going in is too set against any other argument. You surely didn’t mean this?

My prejudice going in to Genesis? That might be true, because I’ve read it and I just don’t see it doing the things that I think need to be done — I’m hoping someone can talk me out of it but it might be a lost cause. Noah and Suat’s arguments are just much more convincing to me than Alan’s, although I’ll read again with this particular set of issues more explicitly in mind. It doesn’t feel like a review from a rigorously literary perspective to me.

Not all critical reviews are satisfying either, though: Bloom’s review also concludes that the images fail the text, but it isn’t satisfying at all — it’s just snobbish. But it’s clearly from a literary point of view. Alter’s review is satisfying because it starts with the specifically literary terrain and pinpoints how and why the images fail, in ways that feel observant rather than loaded. What I’m looking for is a review that starts from the specifically literary terrain and pinpoints — equally without loading — how the images succeed.

It’s from that perspective that most of the arguments I’ve read seem too easily subsumed within this “translation” metaphor. It’s a loose metaphor, obviously biased to reflect my personal experience. But I guess I’m seeking a path into the book where it doesn’t fit at all.

Chris is digging out Promethea now…and I’m headed to dinner — more later!

What do you mean ‘from a rigorously literary perspective’? And why is that preferable? To me good criticism is about engaging with the material in any way that is interesting, really. As I wrote, I think Alan does a good job of demonstrating why Crumb’s images are so much more than ‘translation’.

Oh, and enjoy dinner!

Thanks, dinner was great!

To answer the question about what I mean by “rigorously literary” and why it’s important: first, I think Alter’s critique deserves an equally savvy response from within comics criticism: the observation that images concretize and flatten the Biblical abstractions, discriminations and “slides,” is “rigorously literary” in the sense that it starts from a full appreciation of what’s going on in the Biblical text. Alter’s presentation of the merits of the source material doesn’t miss or downplay anything that would be readily apparent to a savvy literary reader. To be convincing, a corrective to his critique (of the limits of the comics form) needs to also not miss or downplay those things.

To understand what I mean, contrast, for example, with a sentence like this from Alan’s review:

“The scene of Jacob’s prophecy to his twelve sons gains a dramatic force and psychological interest that it cannot have in text alone, where its poetic nature, one of the oldest pieces of writing in the Bible, is much more apparent.”

That sentence says that the text has less “dramatic force and psychological interest” than the pictures, presumably due to its poetic nature. That’s just — well, let’s just say that’s not my experience of this poetry, let alone of poetry period. Pictures are not more emotional than prose and poetry. They just convey that emotional information differently.

That kind of statement doesn’t actually convey a sophisticated understanding of or theory about how the pictures create or elucidate that emotion: it just conveys a less-than-sophisticated understanding of prose. That passage in the Bible, in text, as written, is already dramatic and psychological. It doesn’t take a picture to make a savvy reader realize the drama and psychology of that scene. Nobody who fully appreciated the prose would say something like that! We should not need to denigrate or misrepresent prose in order to praise comics.

Defenders of the book don’t speak convincingly about these most literary elements, and when they do touch on them, they suggest the concrete images are either preferable or at least more accessible. That makes them unpersuasive as responses to Alter’s point. Alter’s review suggests that the original prose is for advanced readers who can appreciate that “un-flattened, abstract” interplay of the text, and that the comic is a good representation of some elements but ultimately for less advanced readers who either have trouble with the prose or just don’t value the Bible’s most literary elements. If you really think this book is a significant achievement, you should not be satisfied letting those assertions stand unchallenged. At this point, I have read no response to them that really seems to understand and appreciate what Alter said was lost.

Which brings me to my second point, answering your question of why it’s important to get the literary perspective right (in this case and in general): If the impressive achievements of comics can only be articulated in comparison with a dumbed-down version of literature that isn’t actually recognizable to people who read a lot of literature, that’s a critical failure.

Now, if the truth of the matter is that most people who like Genesis really can’t get that psychology and drama out of the text and the pictures make it accessible — the “universal” idea that the Bible is hard and that pictures are clearer — that’s a perfectly acceptable justification for making this book, but it’s one that can be easily subsumed into my notion of “translation,” because it’s not true that for all readers the pictures are more accessible.

But I do not want the critical bar to be there, with comics as “easy readers” or as a crutch for hard prose. I think that is a problem with the way we think and talk about what comics do, not what comics actually are capable of doing.

That’s why it’s important to get the representation of literariness right — at least when discussing “literary” comics, or the literary merits of comics. (The same arguments could be made about visual art as well, although comics seems far more mature in its approach to art than literature to me. Perhaps an art historian’s mileage varies on that…)

I don’t mean that there’s no other review that’s worthwhile. I just mean that that specific review, the one that really responds to Alter, really needs to be written. I can’t write it, because I agree with Alter. But I’m waiting for someone to change my mind.

Harry Potter, now Bloom on Crumb. He’s out snob on a string. They should get him to watch Gossip Girl for a season.

‘our’

Caro, thanks for clarifying. In my piece for today I will touch upon that issue at least briefly, though it’s strange to me that you can’t just see Crumb’s work as exegesis. Let me put it this way:

Does Kierkegaard’s retellings (mentioned by Noah in his piece) of the story not denigrate the integrity of the original text? He concretizes emotions and situations that are not there explicitly in the bible — doesn’t that ‘flatten’ it, by your (and Alter’s) logic?

Kierkegaard goes out of his way *not* to flatten it. His reading is a multiple reading; if you look at the original text, he comes back to the same sequence (Abraham sacrificing Isaac) again and again, looking at it from different angles, finding different stories in the on story. And then he finds analogies in other texts, comparing it to Agammemnon’s sacrifice, to various fairy tales, and throughout by (not very far) buried analogies to his own life and by (somewhat more buried) analogies to Christ. And, of course, Kierkegaard’s philosophical interests and explications are far more sophisticated and engaged than Crumb’s. Fear and Trembling is a fractal, passionately engaged effort to come to grips with the issues of faith and love as expressed in a handful of Biblical verses. His treatment obsessively emphasizes the literariness and ambiguity of the text. I just don’t see Crumb doing that anywhere — not in the Abraham/Isaac story, not in the rest of the book.

I agree, but my point is that Crumb doesn’t flatten things either. He uses images, while my compatriot Kierkegaard uses words, which makes a huge difference to the nature of their achievement (even without comparing their individual merits).

Well, I wait to be convinced!

Hey Matthias — I’m looking forward to reading your piece!

Alter’s “flattening” specifically describes how the images get in the way of a certain category of abstractions. He says:

It’s not a flattening of affect. Alter’s review clearly suggests Crumb got the affect fine. It’s a flattening of the ambiguity generated by the complex formal interplay of the technical elements and cultural referents of the Bible’s language: syntatic imbalance, etc. Kierkegaard shifts the emphasis onto a subset of ambiguities, but there are still ambiguities. There would have to be an equivalent ambiguity generated by the complex formal interplay of the technical elements of the comics images, or something similar, in order for the flattening not to occur. That’s why it’s a point about abstraction versus concretization.

That’s why it’s not sufficient to say that representational images just do this differently — how do these representational images generate ambiguity? Like Alter, they seem more consistently concrete to me.

So the complaint isn’t that Crumb “denigrated” the Bible: it’s that he simplified it. I hope you’ll be able to show me that complexity and ambiguity after all!

I can’t see it as exegesis because there isn’t enough commentary. Exegesis is not about retaining the experience of the text; it creates a critical distance on the text, filling in context that isn’t literally present, illuminating debates, clarifying philology. Biblical annotations don’t summarize each verse they describe.

Crumb absolutely uses exegesis in developing his depictions, and some of the pictures quite compellingly allude to or represent content from the exegesis, but he doesn’t create a new work of exegesis. Again, it seems to me he translates an exegesis we’ve already got into pictorial form.

Caro wrote, “[Alan’s] sentence says that the text has less “dramatic force and psychological interest” than the pictures, presumably due to its poetic nature. That’s just — well, let’s just say that’s not my experience of this poetry, let alone of poetry period. Pictures are not more emotional than prose and poetry. They just convey that emotional information differently.

”That kind of statement doesn’t actually convey a sophisticated understanding of or theory about how the pictures create or elucidate that emotion: it just conveys a less-than-sophisticated understanding of prose. That passage in the Bible, in text, as written, is already dramatic and psychological. It doesn’t take a picture to make a savvy reader realize the drama and psychology of that scene. Nobody who fully appreciated the prose would say something like that!”

Well, I’ll defend myself against that. Jeez. That doesn’t describe how the original poem in its narrative setting read to me. It brought a somewhat spectral view of the scene to mind, the way when you’re reading any long, poetic speech in an ancient work you concentrate on where the words are taking you rather than wonder what the characters are doing as the seconds creep by, or at least I do.

Reading the poem made me dwell on each of the characters in a more interior way- and flip back through the book trying to remember who did what and was born under what circumstances- and seeing the judgement pass to each of them was a different experience, dramatic and psychological in the sense that you focus on how they’re taking it. The ancient song is concerned with the judgement itself, and the narrative has no hint of whether it affected them- that’s wholly left for you to fill in if you’re so inclined.

Which is fine (it’s just not the same as a set-piece speech in dramas we’re used to,) it’s just different. Throughout, I was trying to appreciate what Crumb brought to his adaptation, not claiming anything made it better in some “let’s hold the Mona Lisa next to this panel of Lucy in her advice booth and see who wins” method. The temptation to give it this or that rank among comics, Bible art, etc. faded away as I decided it was important to work out what it was first.

Alter, I thought, was basically explaining why the adaptation was not “the Bible, now improved with pictures,” which might make sense to an English professor as he passes the graphic novel section at Barnes and Noble, but I doubt would occur to people who are used to comics and see it as a treatment. I guess I can’t say I did bring the rigorously literary perspective Harold Bloom applied when he said the women weren’t pretty enough and chucked it over his shoulder.

I thought Noah did a good job of pointing out the kind of lightly mocking touches that you miss when you’re looking for ways to defend something to religious people. Even though he was making fun of me, I liked his review better than others I’ve seen here because he focused on the comic, and didn’t just try to bring in pieces that he thought countered it. The Kierkegaard is the kind of comparison that helps bring something out. I don’t know where I stand on that. I do think the problem with all of these more openly personal treatments- as opposed to a subtly personal one, that lets the text lead and reacts in different ways- is that it’s much more easy for institutions who have an interest in claiming the text means certain things to dismiss them as “that’s the artist,” “that says more about Kierkegaard,” which I have heard.

”…and that the comic is a good representation of some elements but ultimately for less advanced readers who either have trouble with the prose or just don’t value the Bible’s most literary elements.“

The thing is, I see a lot of condescension to ”less advanced readers“ here, but we’re all students. I think I’ve given the Bible a more serious look than your average secular nonacademic, and I had trouble keeping Jacob’s sons straight. They’re important, because they become the twelve tribes of Israel, major factors in the rest of the Bible. I’m suspicious- can the secular people here really, truly say they already had a firm grasp of them? Their birth in that kind of duel between Leah and Rachel, the circumcision and slaughter at Shechem, Reuben sleeping with his father’s concubine, Judah showing pity to Joseph? Really? I saw people talking about Crumb’s handling of famous landmarks, and acting as if Christian paintings were illustrations from the same narrative.

His is a useful guide, which is not the end-all-and-be-all but also wrong to keep selling short- and an artist’s play on the text, the nature of which we’ve been debating. There are times when the poetry rings out in this oblique approach of filling in the context with pictures, and times when it recedes.

Alan, they’re all good points, but Alter’s observation about the concretization of images amounts to saying that the comics idiom, in the representational sequential form that we conventionally understand it, is incapable, inherently incapable, of ever producing a book for which one target audience is people with advanced degrees in literature — “advanced readers”. He is saying that comics can’t do it. Not just Crumb’s book, but all books in that tradition. Period.

That’s a very significant criticism. You can call it “condescension toward less advanced readers” to insist that it be dealt with if you want, but it’s nonetheless a very powerful statement that comics in their traditional form aren’t really worth the time of PhDs because of their inability to convey sufficient abstraction and keep ambiguity in play. Despite all the hulabaloo about “literary comics,” for the most part comics are not literary yet — for the specific reason that Alter identifies.

I agree you gave it a more serious look than the average nonsecular academic. But that’s not the issue. The issue he raises is whether or not the idiom itself (traditionally defined) shuts down the highest level of literary reading, making it impossible or very difficult.

Your talking about how the pictures help overcome the distance of the prose for particular readers is indeed giving them a fair shake on their own terms, a fairer shake than most people have given them. But it isn’t defending them against Alter’s charge that they are inherently more limited, more concrete, less literary/artistic than the source material. From my perspective, what you call “spectral” is precisely the same thing as the “hovering ambiguity” that Alter says makes the text literary. You describe what I call translation: pointing out how the comics idiom helps people who are not completely 100% fluent in the original source idiom to make more sense of it.

I agree the book works just fine as this kind of “translation” — for the reasons you give and others — but that still doesn’t push it over Alter’s bar.

That’s why I’m saying somebody who actually feels the book is an achievement beyond translation needs to start with Alter’s reading of the source — not mine, not yours, but the best, most dextrous, most fluent reader of the Bible working right now, who has taken the time and effort to make his reading available to us through his own exegetical writing — and talk about the ways in which either this comics treatment does target that type of reader, or the ways in which a better comics treatment could target that kind of reader, while still working within the comics tradition. Otherwise Alter’s still saying “it works, but it’s still comics, and as with all comics, too much is lost for a reader who is really fluent with the prose.”

Of course, comics criticism as a critical practice can absolutely make the claim that it has no reason or responsibility to speak to literature “professor[s] passing by the graphic novels section at Barnes and Noble” but only needs to speak to “people who are used to comics and see it as a treatment,” but tell me again how that isn’t insular? Or is the point in fact that English professors shouldn’t read graphic novels unless they’re willing to leave their well-trained, well-read brains in their offices while they do? That doesn’t satisfy me, because that’s what I was saying when I objected to the idea that comics-as-literature should have no loftier goal than being an “easy reader” to help people make sense of difficult and truly literary prose.

But at the same time, “comics-as-literature” can’t get around this problem by redefining literature to mean something that comics do naturally. That’s just as much a critical cop-out as the approaches you’re criticizing Suat and me for…we may or may not be selling Crumb short, but you’re selling every comic ever written short in order to defend him…

Just to be clear, Caro — you don’t actually think Alter is correct, right? That is, you think that there are comics which are successfully literary (like Clowes and Feuchtenberger?

I think a word-for-word translation of Genesis could have managed to do more with ambiguity in various ways. As I mentioned, I would have liked to have seen Chris Ware tackle the begats. Also while reading I was wondering what it would have looked like to have more aggressively juxtaposed the two creation of man stories, perhaps on a single page. Something like Kierkegaard’s multiple readings at once could also be done through images while keeping the same text (you could see the sacrifice from Abraham’s viewpoint, from Isaac’s, perhaps from God’s.) There could have been a lot more done with questioning the physicality of God, perhaps by having his words spoken or thought by others. You could do something with multiple biblical translations of particular passages, thus undermining the idea of a “single” text in a more concrete (but not less ambiguous) way than you can manage thorugh exegesis. You could possibly move towards abstraction, a la Gary Panter or Jim Woodring or some of Crumb’s own earlier efforts. You could more aggressively use the history of cartooning, like Maus (not sure this is such a good idea, but it would at least be an idea.)

I don’t know. I’m sure other folks could come up with other ideas. I don’t get the sense that Alter is very familiar with the comics form or with the resources it has available. That’s in some ways an indictment of Crumb as much as Alter, though, since Crumb obviously wasn’t able to demonstrate the breadth of those resources in a convincing manner to a sophisticated but uninitiated reader.

Caro said, “Alter’s observation about the concretization of images amounts to saying that the comics idiom… is incapable, inherently incapable, of ever producing a book for which one target audience is people with advanced degrees in literature — ‘advanced readers’. He is saying that comics can’t do it. Not just Crumb’s book, but all books in that tradition. Period.“

I think- hope- you mean comic book adaptations of this nature, not comic books ever producing a book for “advanced readers.” In the optimistic sense, I think I’ve explained how this gives a fresh look even for people who know the Bible very well. Alter described that effect in some places. If you mean it the way it reads, that’s a crude understanding of comics. I’m also suspicious of any argument that invokes “advanced readers,” or something like that, as some standard. Who are they? What do they bring to bear? And is that any way to argue? By the way, all the smart, attractive people who are going places would agree with what I’m saying right now.

“…it’s nonetheless a very powerful statement that comics in their traditional form aren’t really worth the time of PhDs because of their inability to convey sufficient abstraction and keep ambiguity in play. Despite all the hulabaloo about ‘literary comics,’ for the most part comics are not literary yet — for the specific reason that Alter identifies.“

I would have called it a rather thoughtless statement, but give Alter a little credit, he didn’t talk about what’s worth a PhD’s time.

First, the “but Rebekah loved Jacob” panel actually does keep ambiguity in play, and the suggestion that Isaac’s judgement is faulty for loving Esau because he brings him venison is absolutely kept intact, and suggested in a magnificent little sequence of panels to accompany that sentence. Alter wasn’t reading the comic carefully, but it’s not his field- that’s why PhDs are not almighty.

Second, Alter criticized the story of Er- “And Er was evil in the eyes of the Lord, and the Lord put him to death-” for offering only one possibility, and shutting down ambiguity. I still think that’s only a problem if people decide they don’t need to read the Bible itself (should Crumb have included a disclaimer?)

But I can think of one way to defend the ambiguity of comics. An ambiguous treatment could have shown Er doing something normal in the first panel, “And Er was evil in the eyes of the Lord,” like chatting and laughing with friends, and the second panel “And the Lord put him to death” could have shown him lying prone in a field somewhere. Imagine it drawn by Fletcher Hanks. Ambiguous enough?

The reason I don’t think that means I know better than Crumb is that for the audience, the scene was likely not intended to communicate the terror of living in an arbitrary universe. Er, referred to this way, was likely a figure the audience knew, spoken of the way we might talk about Bill Clinton without needing to explain the Lewinsky saga. Who knows, maybe some people thought he was a hero. So Crumb gave us a fair guess that your more serious readers, or anybody who cares enough to look at the words, can dispense with as they like.

“The issue he raises is whether or not the idiom itself (traditionally defined) shuts down the highest level of literary reading, making it impossible or very difficult.“

I guess I think it’s just one way in, from a certain angle, that turns up some gems. Surely academics are used to such an idea, using a variety of frameworks to analyze something, and I’m pretty sure they can handle it.

“You describe what I call translation: pointing out how the comics idiom helps people who are not completely 100% fluent in the original source idiom to make more sense of it.“

NOBODY IS. Not Hebrew scholars, nobody. I still say it’s interpretation, and Alter, and Suat, didn’t have a problem calling it exegesis- I really don’t want to get back on him, but his objection seemed to simply be to a poverty of interpretation, interpretation that ignored a higher level, not something that didn’t do it at all. You have to interpret to bring it out in pictures, in so many ways- have to develop an idea of who the characters are, maybe not in such a profound way as I made it sound and Noah shot down.

But just from flipping through the book, the scene of Leah’s “baby contest” with Rachel has a panel of her children attacking each other while she scolds them with the same expression, and the text is only “And afterward she bore a daughter and called her name Dinah.” That sets up what the kids are going to be like, and suggests they get it from her- fits nicely with the Hebrew etiological perspective.

Here’s a better one: God appearing as a kind of science fiction character who creates a world and wanders around in it, befriending some of its creatures, in the pre-Flood scenes is an interpretation. It sets him up as a really bad administrator- everyone seems to accept his presence as “that guy who runs things,” and yet he doesn’t, he lets people run rampant, destroys them, and repents from it when there’s no suggestion they’ll improve. That creates a moral frame for the story, in which Joseph’s climactic line “I am not God, am I?!?” sets up a nice, and moving, resolution, even if he looks like an actor. The line is punched up by Crumb from the original. God can do whatever he likes but we have to be better. That’s an interpretation.

“That’s why I’m saying somebody who actually feels the book is an achievement beyond translation needs to start with Alter’s reading of the source — not mine, not yours, but the best, most dextrous, most fluent reader of the Bible working right now, who has taken the time and effort to make his reading available to us through his own exegetical writing.“

That brings us back to Jeet’s call for a Biblical/cartoon scholar, because Alter’s reading of the comic as a comic is sloppy. Too bad Jeet isn’t here. And none of us are that scholar, but we can try, and build on and dismantle each other’s cases until we get a sharper look at what this comic does, and then we can rank it… or let it settle in place.

“Of course, comics criticism as a critical practice can absolutely make the claim that it has no reason or responsibility to speak to literature ‘professor[s] passing by the graphic novels section at Barnes and Noble’ but only needs to speak to ‘people who are used to comics and see it as a treatment,’ but tell me again how that isn’t insular?“

The scenario was presented to point out how literary people and guardians of the canon can feel threatened by comics, and worry about them as a replacement. Nobody in comics thinks that way. But a New York Times Magazine article that came out a few years back, covering Clowes, Ware, Brown, etc., opened by saying comic books might replace the novel. And this was a positive article. A fiction writing teacher- a published author who needed the money, like so many- in a class here in New York responded to my description of myself as an aspiring comic book maker by saying, “People are saying they’re going to… replace… novels?” with a tight little smile on his face, and seemed genuinely relieved when I said no.

The thing is, even smart people get goofy when they feel threatened. Are you going to tell me that people who associate themselves with literature, people in English departments, don’t feel under siege?

Ha ha ha ha ha ha ha.

That mentality means they’re not always in the best position to really look at comics and work out what they do. It doesn’t mean we shouldn’t listen, or evaluate their arguments on their strengths- I think I have contested specific points Alter made, all over. I like reading articles from non-comics people, because they’re not advocacy. (God, that gets old.) Sometimes they make good points. The best takes on Watchmen came when that movie came out and some real-world critics worked in some stinging descriptions of the book. And Alter made some good points about the Bible.

“’comics-as-literature’ can’t get around this problem by redefining literature to mean something that comics do naturally… we may or may not be selling Crumb short, but you’re selling every comic ever written short in order to defend him…“

I have no idea where I do that. I do encourage really looking at things, though.

Right, Noah; absolutely. I definitely think Clowes and Feuchtenberger are successfully literary — in the case of Feuchtenberger, game-changingly literary. But W the Whore and David Boring also are not really using “traditional comics tropes” and I think it’s harder to defend traditional comics tropes and techniques against Alter’s critique. The tropes and techniques you describe would be comics and they would not have Alter’s problems, but they’re also not “traditional” in the sense that Crumb’s work is.

So like you said in your last paragraph: it’s a major limitation of Crumb’s book that it’s hard to use it to argue against Alter.

It doesn’t mean that traditional comics don’t do other interesting and good things. But this is something that has been identified as an inherent limitation, and I think it should be addressed. What are the ways in which traditional comics pushes back against Alter’s criticism, without redefining the experience of prose “literature” so that the bar is lower?

If I were going to argue against Alter, I’d use Kim Deitch, who is more traditional than Clowes and Feuchtenberger, but still extremely subtle and textually rich. But I’d be emphasizing elements that still aren’t there in this Crumb, which is why I want to know whether a defense that’s consistent with liking Genesis can also respond to Alter.

Noah wrote, “Also while reading I was wondering what it would have looked like to have more aggressively juxtaposed the two creation of man stories, perhaps on a single page.”

He does that on the first page of Chapter 2.

“You could do something with multiple biblical translations of particular passages, thus undermining the idea of a “single” text in a more concrete (but not less ambiguous) way than you can manage thorugh exegesis.”

Alter describes in his introduction how these works aren’t “books” as we understand them, but scrolls that were often added onto with new pieces of parchment. Reading that crystallized what’s appropriate about that page, where we swiftly rewind to second scene of creation, right in the middle- it conveys the way the text was put together.

For the genealogies, I get more out of looking at faces than sperm, myself. I thought you didn’t like Ware…

“That brings us back to Jeet’s call for a Biblical/cartoon scholar”

I’m sure Suat would say he’s neither a Bible scholar nor a comics scholar…but I doubt there’s anybody else out there as well versed in both theology and comics. So Jeet sort of got his wish…though not in exactly the way he hoped, as often happens.

I think Crumb could have done a lot more with that juxtaposition; as it is, I don’t really see how reading the text alone wouldn’t have the same effect — which gets back to Caro’s discussion of translation.

“I thought you didn’t like Ware…”

I have mixed feelings about Ware. I like his early work quite a bit. I think he’s run aground somewhat for reasons of content…so having him illustrate another text could possibly be a way for him to do something I really liked (not that he’s attempting to please me, of course.)

I disagree entirely that Alter didn’t read the comic carefully, but are you saying that Alter only makes the point about concretization because he feels threatened, or is that just a point about fiction writers?

I mean, I really do not feel under siege. Not even a little bit. There are enough extraordinary prose books already written to keep me busy for the rest of my life and a couple lifetimes more. I guess I can see how fiction writers might worry about a dwindling audience as more people like comics more and prose books less, but I can’t see how that would bother someone like me or even someone like Alter. Neither of our livelihoods depend on the popularity of prose…

Also, I really really like great comics like the ones Feuchtenberger makes (and Kim Deitch and a whole bunch of others) and I would be completely and totally ok if the rest of literary fiction ever created for the rest of time was JUST LIKE THAT. In fact, I’d be a great deal happier with that than with what we’re currently getting for “new” literary fiction.

But shelves upon shelves of books like Crumb’s Genesis? That’s just sad. That’s like all Fox and no HBO.

I both challenged Alter’s points a number of times and characterized his judgement as “there are things you get out of reading the Bible that you don’t get from this.” Then I sketched out the siege mentality canonical defenders have that could lead to such a seemingly pointless judgement.

I never, ever suggested you might feel under siege, I was expanding on my description of the highbrow, PhD, literary, serious reader’s perspective you invoke, in order to respond to your characterization of my description as “insular.” I have no idea of your background or setting at all. Were you talking about yourself?

I do, absolutely, think prose gives us things comics don’t, if there’s been any doubt of that at any time.

“But shelves upon shelves of books like Crumb’s Genesis? That’s just sad. That’s like all Fox and no HBO.”

I don’t see any more on the march, and that’s a weird, weird description of the book I’m looking at. Fox speaks from a fundamental sense of ignorance and self-involvement- not compatible with putting yourself aside to closely read something, as Crumb did. His approach reminds me a bit of HBO’s Rome, which I liked for not whitewashing the different moral values of the time, and putting them only in the mouths of bad people the way every historical film does. You could call that “sensitive to difference.”

Alan, have you read my essay on W the Whore Makes Her Tracks? Feuchtenberger is just a really really good comics example of “literary” conceptual ambiguity, and that’s closer to what I think Alter’s talking about…I see what you’re saying about Crumb’s panels, but I don’t think it’s the same thing. What you’re describing is there, but I don’t think it’s an example of what Alter says is missing, so I don’t think it’s a response to Alter.

Saying that scholars like Alter see limitations in Crumb because they’re guarding themselves against a siege is just inaccurate. Insofar as “the literati”/ feel beseiged, TV and corporate-think are the “enemies” — because television and marketing reduce the overall criticality of a population. (The possible exception may be the fiction writers: I don’t know any professional fiction writers so I can’t say.)

I no longer work in a university — I left academia after my exams because I did not want to teach — but I do have active ongoing academic work and my education and background are from that perspective, so I share that perspective, and I routinely talk to people who do still work in academia. There’s no “threat” from comics at all. Any sense of seige comes from business imperatives within universities and publishing houses and an overall decline in critical thinking and attention span period, not a particular decline in prose literacy.

The things that threaten prose literature in our culture threaten literary and art comics too, and if comics can help stave them off, I think most literature-loving people would be overjoyed at that. Expecting comics to reach for that higher bar — like Noah and Suat and I all did in various ways — is not some subversive tactic for killing them off or breaking the siege. (Talk about a war-like mentality.) It’s just asking for people who like the things we value (which aren’t all the same thing!) to be included in their audience.

Well, it looks like poor Matthias wasn’t quite able to finish his post on this for today…and next week we have a roundtable on a different subject, so I think that means he’ll be posting next Sunday. It sounds like Matthias’ post is a doozy, though, so it’ll be worth the wait I think!

Caro wrote, “Saying that scholars like Alter see limitations in Crumb because they’re guarding themselves against a siege is just inaccurate. Insofar as “the literati”/ feel beseiged, TV and corporate-think are the “enemies” — because television and marketing reduce the overall criticality of a population.“

Not buying it. The whole concept of the canon in our time is intimately linked with a sense of siege. Alter is a Biblical scholar, to boot, and few people who aren’t religious read the Bible cover to cover. I’d guess more religious people do, but not so many. I have encounters with academia too, and when I mention comics they start talking about video games as if they’re related.

People whose see themselves as representatives and defenders of the canon- that’s Alter, though he’s also a popularizer, so quit sneering at that- see comics as being part of a tide of new, junk media. This could, of course, describe more of an “old guard” in academia, though I doubt it’s that contained. Culture studies at least doesn’t want to throw comics out with the trash, but it still makes the lump association. They don’t want to take out the trash. Of course there’s a variety of opinion- no surprise, but what I describe is there. Maybe we’ll just have to throw the floor open to other people’s impressions on this. I don’t know how much more carefully I can state my objections to Alter’s take, though.

“Expecting comics to reach for that higher bar — like Noah and Suat and I all did in various ways — is not some subversive tactic for killing them off or breaking the siege. (Talk about a war-like mentality.) It’s just asking for people who like the things we value (which aren’t all the same thing!) to be included in their audience.”

I never said you were doing it yourselves. But while we’re talking about a warlike mentality, I see you defending the tactic of bringing holding paintings up against comic book panels with no context, and other such comparisons, like Clowes vs. Derrida, to see whether they “stand or fall.” That seems like a blunt instrument to me, and it’s aggressive. You might want to refine that tactic a bit. We do try to decide which works are better than others. But first we have to be sensitive to what they are, and comparisons are more useful for that, for contrast, context, and understanding. Art history is not Pokemon.

I also see you invoking authority- credentials, “advanced readership-” to back up your opinions. Suat’s essay also had that sense of authority- the importance of religious interpretation- rolling in to crush this comic, with not a lot of attention paid to what it did. Your piece, though softer toned, was still saying “This is better,” with scant reference to the comic, and a highly dubious opposition set up between “the past” and “moving forward-” the kind we could answer with Bartlett’s Familiar Quotations.

Maybe this will help. I neglected this point in my essay because I was, perhaps unwisely, trying to defend the comic in a religious framework. But it apparently needs to be made very, very clear how authority through the ages has depended on ownership and interpretation of this book. (I would think people who wear their learning on their sleeves would know that, but I see it brushed off. I guess we’re out of those woods today, huh?) What do you think drove anti-Semitism? It wasn’t just “fear of the Other,” like some primal sin we can’t understand. It’s about who owns the Bible, and who gets to say what it means- still a very, very serious thing.

The kind of expressionist, personal, interpretive, modern take you guys have been demanding should be evaluated on its own merits, and a thoughtful comparison could be interesting. But like I said, however fulfilling, such an approach has the weakness that it can be brushed off as “Kierkegaard being Kierkegaard,” an artist’s personal journey. It is also the more necessary, default choice for adapting work from times we know better.

The claim that we know the Bible very well and all this is unnecessary is ridiculous. I get into some ways that’s not true in my essay, and comment #38 right here- check it out if you’d like to argue. Religious people experience it through a structure that tells them what to think. Few secular people really have an awareness of it, even Genesis, past some children’s book highlights. Fiore was surprised by this material, over on TCJ. Francoise Mouly, at the talk here, was saying she’d never read Genesis. I haven’t seen much evidence here of a familiarity that justifies the huffing I’ve seen to readers who might be helped by this sort of thing. That’s me, and it’s you.

These stories, as you point out, likely had currency in some kind of recital at the time. That recital depended on a lost context, and trying to work out when the stories were generated, how, and how they related to reality can make your head spin- try Israel Finkelstein’s books. Filling out stories intended for recital with pictures to establish some kind of context is an oblique approach that can bring some things to light. It has the unique advantage of being a book you can put down and take up again. A dramatic performance, and I’ve heard many movies invoked as being superior over the past few months, which I’ll watch sometime, perforce reshape events (and alter the ethical sense- name one that doesn’t) to keep asses in chairs.