Warning: Spoilers Throughout

The latest comic by Eddie Campbell is conventional in a number of ways peculiar to the form. It is a collaboration with a writer, in this instance Daren White, the editor of the Australian anthology DeeVee. Also familiar is the presentation which is not dissimilar to what you might find in a newspaper strip collection with the panels laid out in single file across a squat rectangular book. The pages only lack the closing punchlines once deemed so necessary to such endeavors, but these occur frequently enough so as to negate any perceived differences; the temporary conclusions and logical ellipses between the pages being the very stuff of modernity (see Campbell’s remarks on the rearrangement of the strip from 9 panels per page to its current format in the interviews below).

Equally typical is the eponymous protagonist who is artistic, misogynistic, and sexually deficient in the grand tradition of many a comic book “hero” from Peter Parker (less contempt for the fairer sex here) to Jimmy Corrigan. The playwright’s powers lie in art and not entomology; his family is largely absent, made distant or directly harmed by his predilections; he rents lodging from an “uncle”; and his final success with a capable and assertive lass made all the sweeter by his innumerable failures at conjugation.

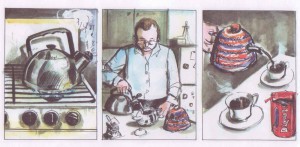

The playwright’s isolation and the sense of “antiquity” overlying the proceedings are suggested by a florid tea cosy and a pack of digestives early on in the narrative. In this he might be seen as an Anglicized Pekar.

He wears a condescension born of his years, an old fashioned sense of his own self-worth, and a belief in his progressive leanings. All this is mirrored in the mannered third person narrative and the juxtaposed imagery, much of which is incongruous and satirical.

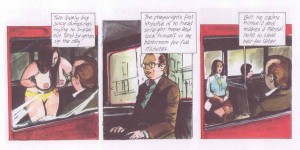

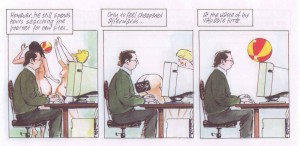

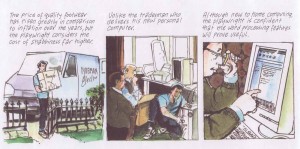

His capers are laid down in chapters titled “On the bus”, “Online”, “In the park”, “At school”, “On the continent” and “Incontinent”; each of these being variations on the themes of desire and plain old lechery: a young girl is pictured bursting forth from her Marks and Spencer blouse while sitting across from him in a bus; …

…he surfs the net for pornography as images from this electronic quest scroll across his study room in sympathy with his mental fabrications; …

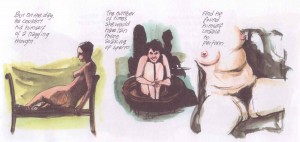

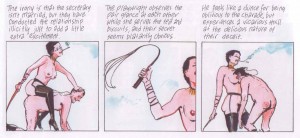

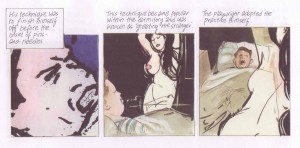

…dick sizes are compared in a boarding school as are methodologies for masturbation; a promising partner encountered at a resort is rejected for her apparent promiscuity and lack of virtue (she is a mirror of his deepest longings), an episode which recalls a prior dysfunctional encounter with a prostitute where the thought of fermenting seminal secretions in the whore’s womb ruins desire.

l’Origine du monde (1866), Gustave Courbet

In fact, every woman the playwright encounters becomes a suitable target for his predatory and totally ineffectual peeks and ministrations. In this way, the comic allows us to participate in his voyeurism and indulge in his sorry escapades.

Having mollified the supplications of mammon and fame, the playwright is now in search of a contentment born of companionship. His art and achievements, once all too easy partners, are now deemed insufficient. His creative impulses formerly milked from his solitude, contemplation and envy now seem worth abandoning.

The story presents a stark choice between life and a kind of artistic parasitism. Thus by the final scene, our hero, having weighed his options, becomes an actor; no longer concerned with solitary processes of creation but participating and collaborating in the theater of life. This is what he sees and covets in the imagined relationship between his accountant and his secretary towards the close of the book: the secret glances, the “blatantly obvious” charade and “the delicious nature of their deceit”; the very essence of burlesque, fleshy carnality, and domination.

In a short review of The Playwright, Robert Boyd indicates that the comic reminded him of “certain stories by English writers like Malcolm Bradbury, David Lodge and William Boyd.” The comparisons are not unwarranted. In campus novels like Bradbury’s The History Man, academic concerns replace the artistic ones presented by White and Campbell. The language utilized can be arch and distant, the spaces for interaction confined. There is a preoccupation with sexual union which is gently mandated by the atmosphere of culture and learning. All of this is saddled with a kind of hypocrisy and self-delusion; the beast within masked by a veneer of respect and erudition. The cynicism here may be compared with the hopefulness of White’s script; the sexual bravado of the protagonists of so much literary fiction in stark contrast to the quiet ineptitude of their comic counterparts.

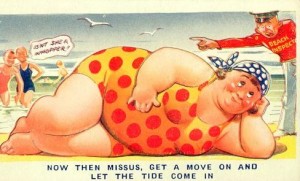

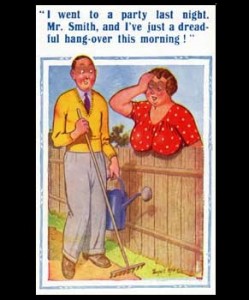

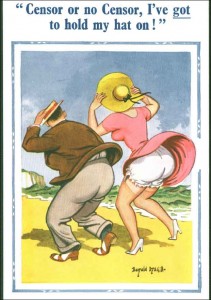

In tone, The Playwright is perhaps closer to the lightness and frivolity of Lodge’s Changing Places or the postcards of Donald McGill which White firmly directs our attention to towards the close of his tale. The stretched dimensions of the comic are in keeping with this subtle homage, but here the comedy is drawn into a more probable reality, the artist’s watercolors accentuating a morphine-laced dream, defacing a middle aged lady’s countenance or highlighting the rolls of flesh on a woman’s belly. Campbell’s attention to detail is found in the precise description of the interiors of a London bus, the intimate disposition of the public houses and, most of all, the unrenovated interiors of a simple English house where the wallpaper and furnishings might well be as old and fashionable as our aging hero.

In relation to this master of the comic postcard, White’s suggested reading is George Orwell’s wonderful essay titled, “The Art of Donald McGill“, where the novelist writes (and I will quote liberally):

“Who does not know the ‘comics’ of the cheap stationers’ windows, the penny or twopenny coloured post cards with their endless succession of fat women in tight bathing-dresses and their crude drawing and unbearable colours, chiefly hedge-sparrow’s-egg tint and Post Office red? … I have associated them especially with the name of Donald McGill because he is not only the most prolific and by far the best of contemporary post card artists, but also the most representative, the most perfect in the tradition…

Anyone who examines his post cards in bulk will notice that many of them are not despicable even as drawings, but it would be mere dilettantism to pretend that they have any direct aesthetic value. A comic post card is simply an illustration to a joke, invariably a ‘low’ joke, and it stands or falls by its ability to raise a laugh. Beyond that it has only ‘ideological’ interest…

McGill is a clever draughtsman with a real caricaturist’s touch in the drawing of faces, but the special value of his post cards is that they are so completely typical. They represent, as it were, the norm of the comic post card. Without being in the least imitative, they are exactly what comic post cards have been any time these last forty years, and from them the meaning and purpose of the whole genre can be inferred…

Your first impression is of overpowering vulgarity. This is quite apart from the ever-present obscenity, and apart also from the hideousness of the colours. They have an utter low-ness of mental atmosphere which comes out not only in the nature of the jokes but, even more, in the grotesque, staring, blatant quality of the drawings…[ ]… I give here a rough analysis of their habitual subject-matter, with such explanatory remarks as seem to be needed:

SEX.–More than half, perhaps three-quarters, of the jokes are sex jokes, ranging from the harmless to the all but unprintable…

Conventions of the sex joke:

(i) Marriage only benefits women. Every man is plotting seduction and every woman is plotting marriage. No woman ever remained unmarried voluntarily.

(ii) Sex-appeal vanishes at about the age of twenty-five.

W.C. JOKES–There is not a large number of these…

INTER-WORKING-CLASS SNOBBERY–Much in these post cards suggests that they are aimed at the better-off working class and poorer middle class…

There is an immense amount of pornography of a mild sort, countless illustrated papers cashing in on women’s legs, but there is no popular literature specializing in the ‘vulgar’, farcical aspect of sex. On the other hand, jokes exactly like McGill’s are the ordinary small change of the revue and music-hall stage, and are also to be heard on the radio, at moments when the censor happens to be nodding….

What they are doing is to give expression to the Sancho Panza view of life, the attitude to life that Miss Rebecca West once summed up as ‘extracting as much fun as possible from smacking behinds in basement kitchens’. The Don Quixote-Sancho Panza combination, which of course is simply the ancient dualism of body and soul in fiction form… If you look into your own mind, which are you, Don Quixote or Sancho Panza? Almost certainly you are both. There is one part of you that wishes to be a hero or a saint, but another part of you is a little fat man who sees very clearly the advantages of staying alive with a whole skin. He is your unofficial self, the voice of the belly protesting against the soul. His tastes lie towards safety, soft beds, no work, pots of beer and women with ‘voluptuous’ figures…

A dirty joke is not, of course, a serious attack upon morality, but it is a sort of mental rebellion, a momentary wish that things were otherwise. So also with all other jokes, which always centre round cowardice, laziness, dishonesty or some other quality which society cannot afford to encourage…

Nevertheless the high sentiments always win in the end, leaders who offer blood, toil, tears and sweat always get more out of their followers than those who offer safety and a good time. When it comes to the pinch, human beings are heroic…It is only that the other element in man, the lazy, cowardly, debt-bilking adulterer who is inside all of us, can never be suppressed altogether and needs a hearing occasionally…

In the past the mood of the comic post card could enter into the central stream of literature, and jokes barely different from McGill’s could casually be uttered between the murders in Shakespeare’s tragedies. That is no longer possible, and a whole category of humour, integral to our literature till 1800 or thereabouts, has dwindled down to these ill-drawn post cards, leading a barely legal existence in cheap stationers’ windows… ”

* * *

In his essay, Orwell begins by describing a certain strain of English humor before proceeding to elucidate the very nature of our inner lives. The comic echoes these traditions: the sex jokes are plentiful; the concerns with bodily functions and the bathroom front and center; the sense of social stratification present from the very first.

The Playwright is a kind of divertimento of the “body and soul”, a short interlude offering a wry look at the moving transgressions of the male eye. Comics is, of course, filled with such diversions, items to be picked at between the more substantial meals which we expect to be placed before us.

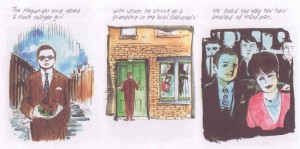

Just as these postcards by McGill might have once been purchased at a “cheap stationers'”, so too did the playwright call upon a “much younger girl with whom he struck up a friendship in the local stationers'”. He “loved the way her hair smelled of marzipan” and finds her “strangely attractive”.

But the encounter degenerates into farce and the author flees in embarrassment; the needs of the flesh once embraced so readily in his childhood now cast aside in favor of something indefinably higher.

But this isn’t a simple transaction between life and art but, as Orwell suggests, a tension within the boundaries of art itself; a tension between a kind of artistic chivalry and the base needs of the flesh. The Playwright is a kind of synthesis of these needs, efficacious in singing its intent but less so in its slightly tired consummation.

Interviews

(1) The Rumpus Interview (Campbell on DeeVee and the rearrangement of the pages and panels)

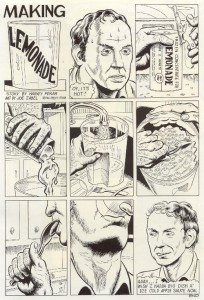

“They put it out as a quarterly between 1997 and 2000, fourteen issues. And they did one special a year after that. Each one had a chapter of The Playwright. Nine panels to a page. But we’ve broken it down and made a little horizontal book out of it and I’ve colored it all and now it looks completely different…”

(2) Interview with Daren White and Eddie Campbell at The Graphic Novel Reporter

Campbell: “The reason that From Hell is so long is that Alan eschewed the use of captions, meaning that the pictures had to do a great deal more work and thus there had to be more pictures. Sticking with captions in this case has tended to trap the reader inside the playwright’s claustrophobic mind, because really we could have done it in the first person.”

White: “I suppose he did grow on me, because it quickly became obvious that he deserved a bigger story. It also meant that it had to be more than a just series of oddball observations played for laughs. There had to be an underlying story… The fact that readers seem to like him, despite his weird, judgmental personality, is very rewarding for me as an author…I think the honesty of his personal thoughts and feelings tends to make the reader take him serious. The challenge was to keep him sympathetic.”

(3) Interview with Daren White and Eddie Campbell at Comic Book Resources conducted by Alex Dueben

Campbell: “…all the interiors now have wallpapered walls which I added using patterns and fitting them to the perspectives of the compositions. That was a lot of work, and it’s really made for a fresh look to the whole thing. All of this is ironic since Daren designed the stories so that I could use a lot of repeated images to save time since there hasn’t been any money in it up till now. I turned the repeats into a feature, zooming in ultra close so that the ink lines became big rough hairy things, and then adding odd little delicate details completely out of scale to the base drawing. Of course, each panel was then colored separately, so the idea of the repeats is buried under all of that…there is nothing “mere” about illustration. It is a craft that has for some reason fallen into disregard. I always thought I was diligently and honestly illustrating the text to the best of my ability. I didn’t add anything that wasn’t in Daren’s script. I simply used all the skills at my disposal to bring out exactly what he was telling us in the story, and I added nothing in the way of diversions or tangents or adornments. I wouldn’t presume to think I could improve upon the narrative…I don’t think I would agree with it being an absolute or a universal paradigm, that the artist must exchange common happiness for success in his art. It would be more true to say that the artist often tends to be a sensitive individual who is prone to unconsciously sabotage his own ambitions. This is the source of the humor in “The Playwright.””

White: “The British sensibility was deliberate and aimed to exaggerate the stuffy, self conscious embarrassment that underpins a certain type of Englishman. I’ve lived in Australia for almost sixteen years now and so have to acknowledge that my fondness for Britain is partially nostalgic. I think there is a sense of longing within the story which comes from this, and I was happy to milk it.”

Reviews

Steve Duin “Because there is far too little finesse in the comics, I’m thankful there are still guys like Eddie Campbell around. The Playwright is a wholly original, painfully astute and — wonder of wonders — surprisingly redemptive…”

Paul Gravett “Campbell’s watercolouring effects take his art into vivid new horizons, at times boldly reusing and reworking faces for later close-ups, even inserting photographic elements and textures. A lovely surprise in the final scene are versions of several naughty English seaside postcards in the Donald McGill tradition. Throughout Campbell’s images skilfully complement and sometimes counterpoint White’s witty third-person, documentary-style narrative, told entirely in text captions. This saucy satirical portrait is pure delight.”

Chad Nevett “White and Campbell give us a window into the life and world of The Playwright, a man who creates great works of art, but doesn’t actually participate in life. Despite the distance in the narration, there’s a great emotional impact as the book progresses, underscored by Campbell’s art. “The Playwright” is a touching and masterful work that is definitely one of the ‘must own’ graphic novels of 2010.”

Parabasis “…loneliness is an inescapable part of creation…[ ]…we filter the world through our subconscious, through our histories, through our identities and cultural contexts and influences and other art works. The distance and the moments of loneliness are essential for this process. I can’t help but think they’re especially essential for comic book artists, which is why there are a lot of comic books out with a basically lonely, misanthropic and/or self-loathing perspective.”

Jamie S. Rich “Perhaps it’s the simplicity of the storytelling, that a few well-placed lines allow for the kind of character development that is so often lacking in other, more effusive tales. It’s not that the playwright has to struggle or earn his happiness, but that by finally meeting life as it comes to him, it affects him at last.”

It’s interesting to reread that Orwell essay. I don’t think when I read it the first time I put it together with actual comics (it was a long time ago.) It’s kind of fun to read his offhand contempt/condescension. I wonder if he ever saw a comic he liked?

I haven’t read this yet, but I am looking forward to getting into it. When Noah was telling me about how he feels comics don’t often measure up to other kinds of art, Eddie Campbell’s work is one of the first rejoinders to come to my mind. And Brad Meltzer, of course.

And Brad Meltzer, of course.

Yes, Identity_Crisis is definetly one of comics’ recent artistic high points. (insert loud squealing sound….)

Pingback: Mindless Ones » Blog Archive » Short and to the Pointless #3: The Playwright