Art by Harvey Kurtzman

The past is a foreign country; they do things differently there.

— L.P. Hartley, The Go-Between

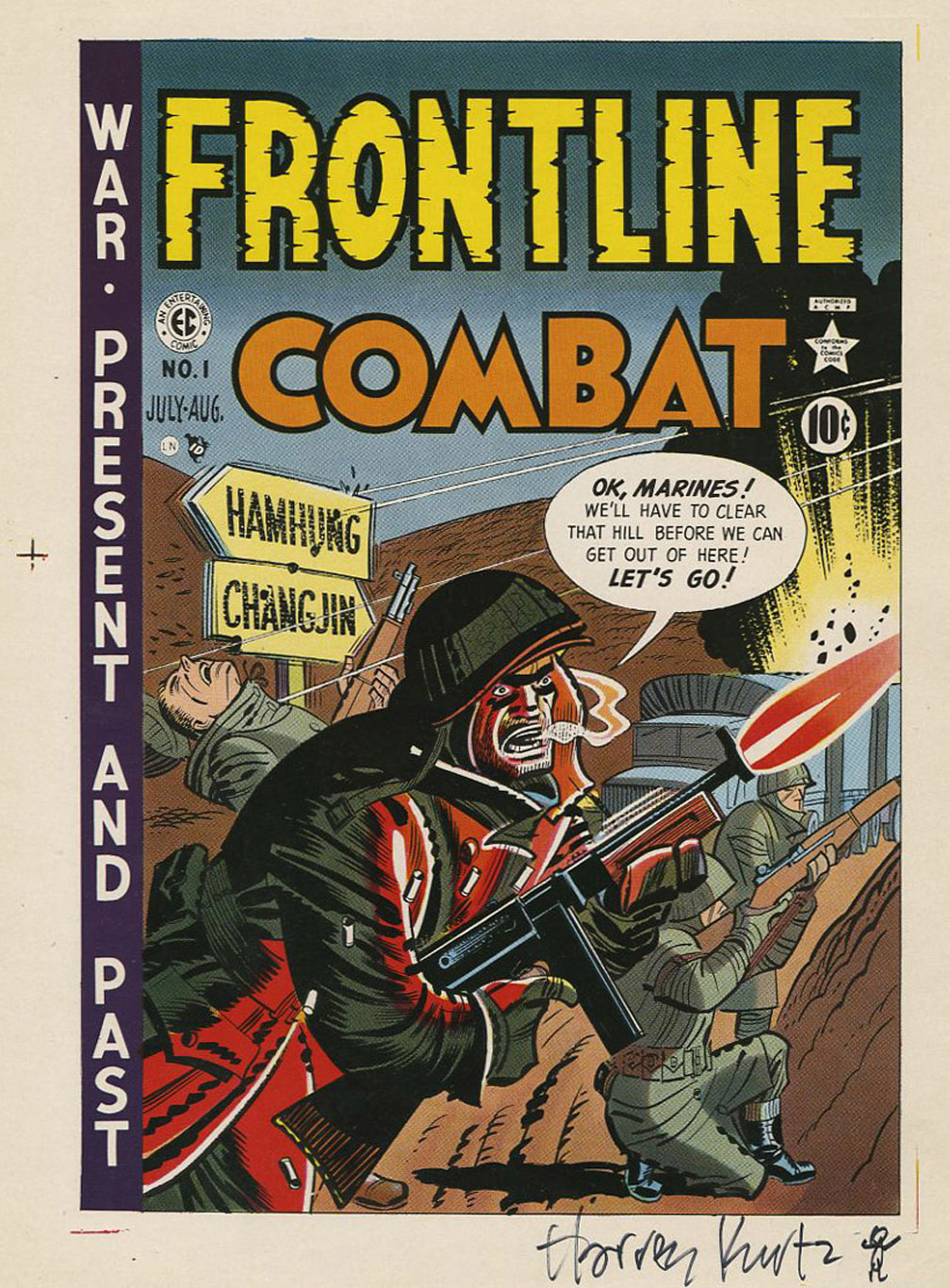

Among the most respected mainstream American comics ever produced are the war stories written and edited (and often drawn) by Harvey Kurtzman for the EC Comics titles Two-Fisted Tales and Frontline Combat between 1950 and 1953.

EC publisher Bill Gaines (left) with Kurtzman

They were praised for their compact but thrilling storytelling (with superior art by such masters as Kurtzman himself, John Severin, Wallace Wood, Jack Davis), their usual focus on the “little people” caught up in the sweep of war, the diversity of their settings– from ancient Rome to the Indian Northwest Frontier to the American War of independance to the Korean conflict–, and their anti-war messages so much in contrast to the gung-ho belligerence of other war comics, such as those then published by Atlas (the future Marvel).

<

Harvey Kurtzman

Kurtzman stated in 1980:

“When I thought of doing a war book, the business of what to say about war was very important to me and was uppermost in my mind, because I did then feel very strongly about not wanting to say anything glamorous about war, and everything that went before Two-Fisted Tales had glamorized war. Nobody had done anything on the depressing aspects of war, and this, to me, was such a dumb – it was a terrible disservice to the children.”

In this he was not always successful: there are many thrilling passages that do, in effect, glamorize war.

<

cover by Jack Davis

A more serious accusation, made notably by Ng Suat Tong in The Comics Journal # 250, is that the stories downplay the genuine horror of war:

“[…] an inability to transcend and communicate the horror and repugnance of stories drawn from first and second-hand accounts[…].”

I find his judgment over-harsh, but won’t debate its merits – the reader is referred to his (excellent) article.

What troubles me is another, admittedly infrequent, failing: examples of historical inaccuracy.

Now, Kurtzman did take accuracy very seriously, and thoroughly researched every one of his stories; consulting primary and secondary sources, interviewing historians. He had no hesitation in demanding redrawing from his artists, some of whom, such as John Severin and George Evans, were themselves passionate amateur historians.

However, as is the way with comics needed to be produced at a rate of a story a week, errors would creep in. These took mostly the form of inaccurate uniforms or anachronistic weaponry, and were by and large harmless.

More troubling are cases when error was introduced for dramatic purposes.

George Evans, an artist obsessed with aircraft, cited one script that called for dust being knocked off a WWI airplane by the impact of bullets.Good visual, bad history: planes were, in fact, hosed down before every flight to remove the dust’s weight.

<

George Evans, drawing a WWI aviation story for Kurtzman at E.C comics

This tendency to rewrite history to make a tidier story (and history is anything but tidy) finds a telling instance in Frontline Combat # 4’s tale “Light Brigade!”, by Kurtzman and artist Wallace Wood.

Artist Wallace Wood, in his E.C. days

It’s a retelling of the famous charge of the British cavalry’s Light Brigade at the battle of Balaclava, during the Crimean War: one of the most infamous screw-ups in military history.

The Crimean War of 1854 opposed an alliance of Britain, France and Turkey against Russia. The entire conflict was a hideous fiasco; indeed, it’s been said that the only reason the allies’ armies escaped annihilation was that their incompetence was matched by that of their enemy.

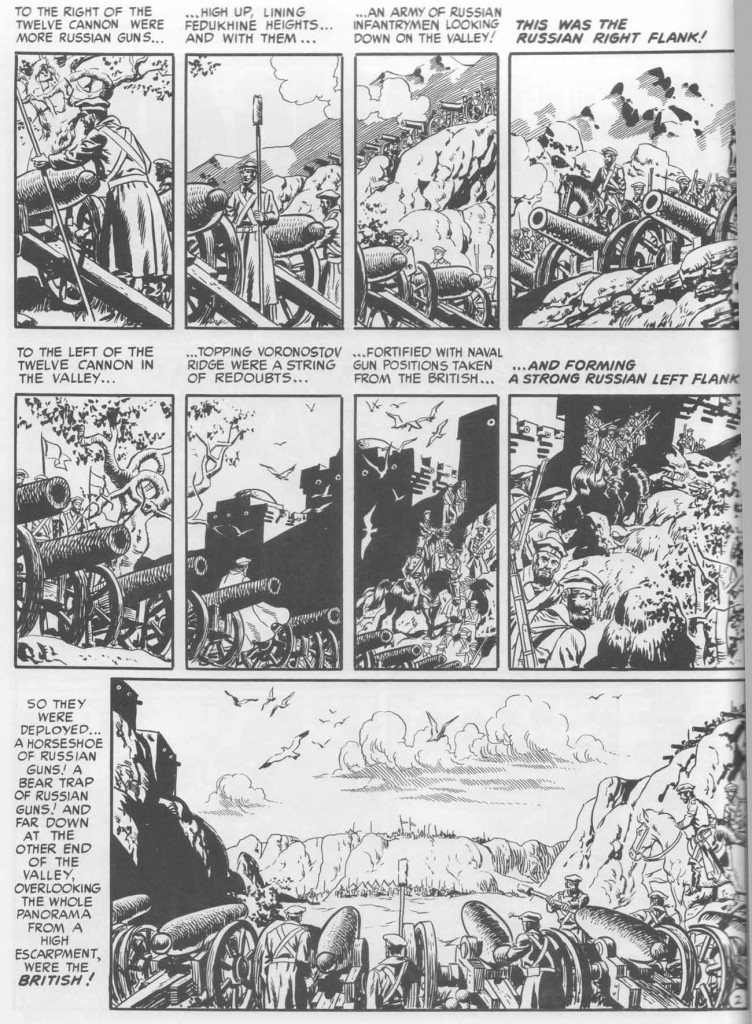

At Balaclava, the opposing armies found themselves facing each other at either end of a two-and-a- half mile long valley hemmed in by hills to the north and south. The Russians had artillery on both hills, and a main battery of 12 guns pointing down the valley on the third side.  From a height, the commanding officer of the allied forces, Lord Raglan, observed the enemy starting to withdraw cannon (captured from the British).

From a height, the commanding officer of the allied forces, Lord Raglan, observed the enemy starting to withdraw cannon (captured from the British).

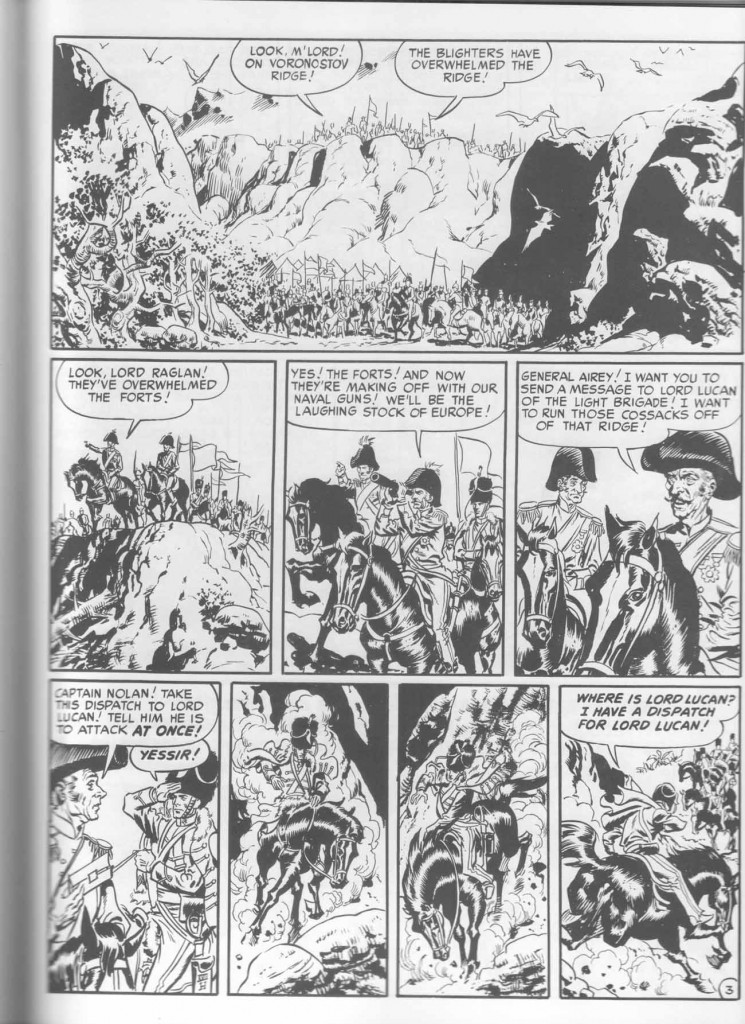

Via his aide, Lord Airey, he sent a fatally ambiguous order to Lord Lucan, the cavalry commander:

‘Lord Raglan wishes the cavalry to advance rapidly to the front—follow the enemy and try to prevent the enemy carrying away the guns. Troop Horse Artillery may accompany. French cavalry is on your left (Sgd) Airey’

The despatch was handed to a Captain Nolan who rode down to the valley below and handed it to Lucan. The latter was puzzled and dismayed by the order. He asked:

The despatch was handed to a Captain Nolan who rode down to the valley below and handed it to Lucan. The latter was puzzled and dismayed by the order. He asked:

‘Attack, sir? Attack what? What guns, sir?”

Instead of pointing at the guns on the south hills, Nolan waved at the end of the valley:

‘There, my Lord, is your enemy, there are your guns.’

And that was the doom of the Light Brigade.

“Forward, the Light Brigade!”

Was there a man dismay’d?

Not tho’ the soldier knew

Someone had blunder’d:

Theirs not to make reply,

Theirs not to reason why,

Theirs but to do and die:

Into the valley of Death

Rode the six hundred.

—Alfred Tennyson, The Charge of the Light Brigade

Lord Cardigan, the general of the Light Brigade– a man as famous for extraordinary courage as he was for extraordinary stupidity– led the charge at a sedate trot. The onlookers, both Russian and allies, could scarcely believe their eyes. A frontal cavalry charge against entrenched artillery? Yes. Seven hundred men rode into the valley. One hundred and ninety-five returned.

Cannon to right of them,

Cannon to left of them,

Cannon in front of them

Volley’d and thunder’d;

Storm’d at with shot and shell,

Boldly they rode and well,

Into the jaws of Death,

Into the mouth of Hell

Rode the six hundred.

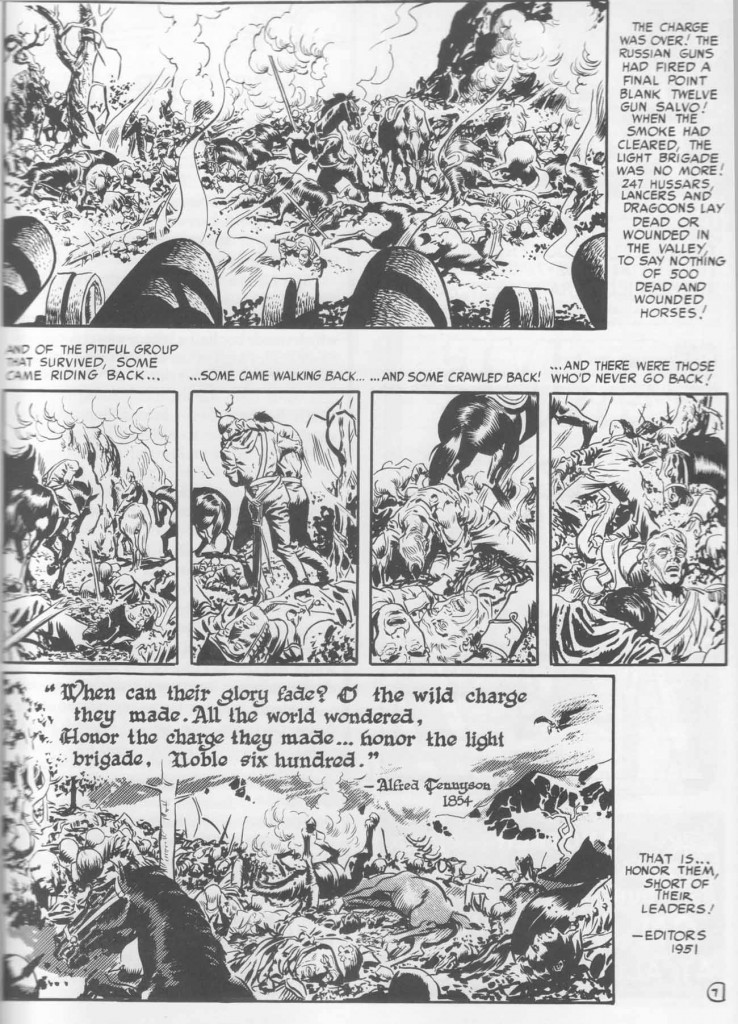

So, where’s the distortion in Kurtzman’s account of the charge? Look at the final page:  The Light Brigade is shown utterly destroyed before it can so much as reach the cannon.

The Light Brigade is shown utterly destroyed before it can so much as reach the cannon.

But this is not what happened.

The Light Brigade actually captured the guns and slaughtered their crews.

Flash’d all their sabres bare,

Flash’d as they turn’d in air,

Sabring the gunners there,

Charging an army, while

All the world wonder’d:

Plunged in the battery-smoke

Right thro’ the line they broke;

Cossack and Russian

Reel’d from the sabre stroke

Shatter’d and sunder’d.

Then they rode back, but not

Not the six hundred.

Obviously, they were quickly repulsed.

But this point is crucial:

They were repulsed by Russian cavalry.

Why did Kurtzman rewrite history?

One explanation is the aforementioned desire for narrative tidiness.

The complete annihilation of the Brigade before it even reached the guns is obviously more dramatic than the real, messy details of attack and counter-attack.

And the short length of the tale (7 pages) precluded any longer presentation, thus inviting over-simplification. (His best war tales are inevitably vignettes, focussing on a single protagonist.)

Ng Suat Tong suggested to me that Kurtzman was employing simple poetic licence to tell a simple tale of war’s horror. But I think there’s more to his shaping of the story than a mere editorial decision.

Error is interesting in that it can expose subconscious feelings and prejudices—think of speech errors such as the “Freudian slip”.

Kurtzman, like so many of his generation, was a technophile.

After all, he came of age at a time that saw the introduction of the atom bomb, radar, ballistic missiles, and so on; it must have seemed normal that newer and more modern military technology would invariably triumph over the old.

Thus, one moral of “Light Brigade” would be: “The time of the cavalry is over; artillery trumps it.”

Yet, as we’ve seen, in reality the Brigade actually did capture the guns, and only the enemy’s cavalry was able to drive it away. Moreover, at the same time a French cavalry regiment, the Chasseurs d’Afrique, succeeded in capturing and holding the artillery-defended redoubts on the southern hills.

And, in fact, cavalry would continue to play a part in warfare for decades; my own father served in an active cavalry regiment in the late nineteen-forties, the French Spahis.

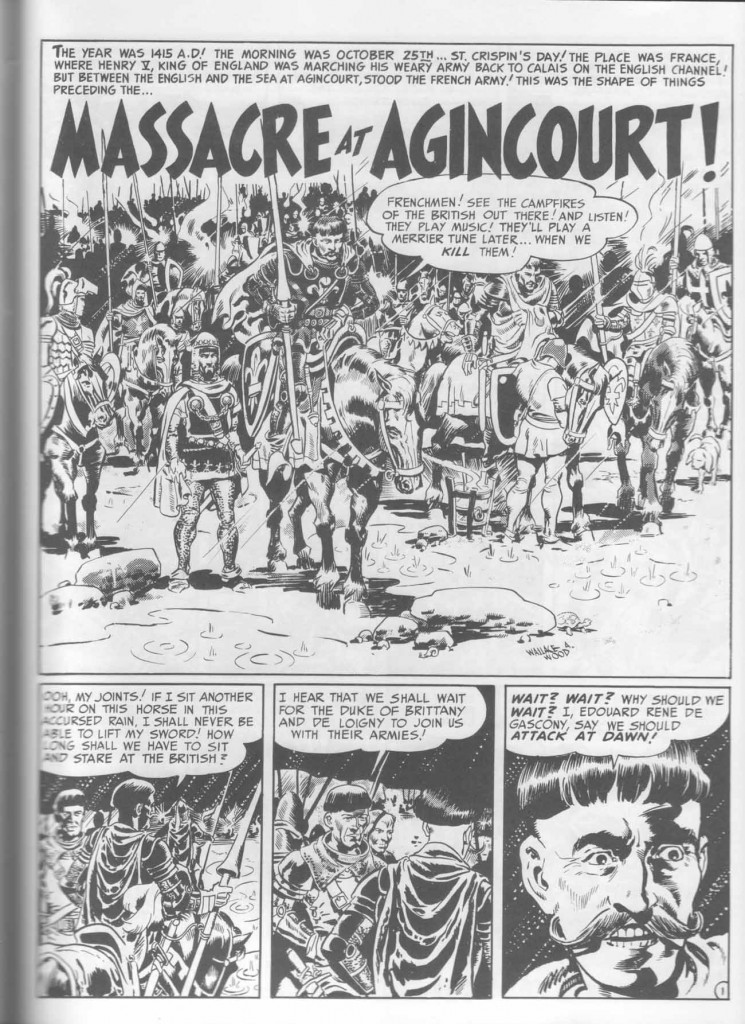

Much the same technophilic ‘moral’ is advanced in a more subtle way in Kurtzman and Wood’s “Massacre at Agincourt!” from Two-Fisted Tales # 22.  In 1415, Henry V of England invaded France, taking the port of Harfleur in Normandy. However, the siege went on too long; this allowed the French to levy a massive army.

In 1415, Henry V of England invaded France, taking the port of Harfleur in Normandy. However, the siege went on too long; this allowed the French to levy a massive army.

Henry and his troops decided to seek refuge in the English-occupied town of Calais, but were cut off from this refuge by the French, near the village of Agincourt.

It is estimated that the French host comprised some 40 000 men, mostly men-at-arms, under the command of the constable Charles d’Abret; the hungry and exhausted English could muster no more than 5000 archers and 900 men-at-arms.

When his calls for truce were spurned, Henry resolved to fight. The English pitched their forces in a narrow field between two woods:

Order of battle at Agincourt: English forces in red, French in blue

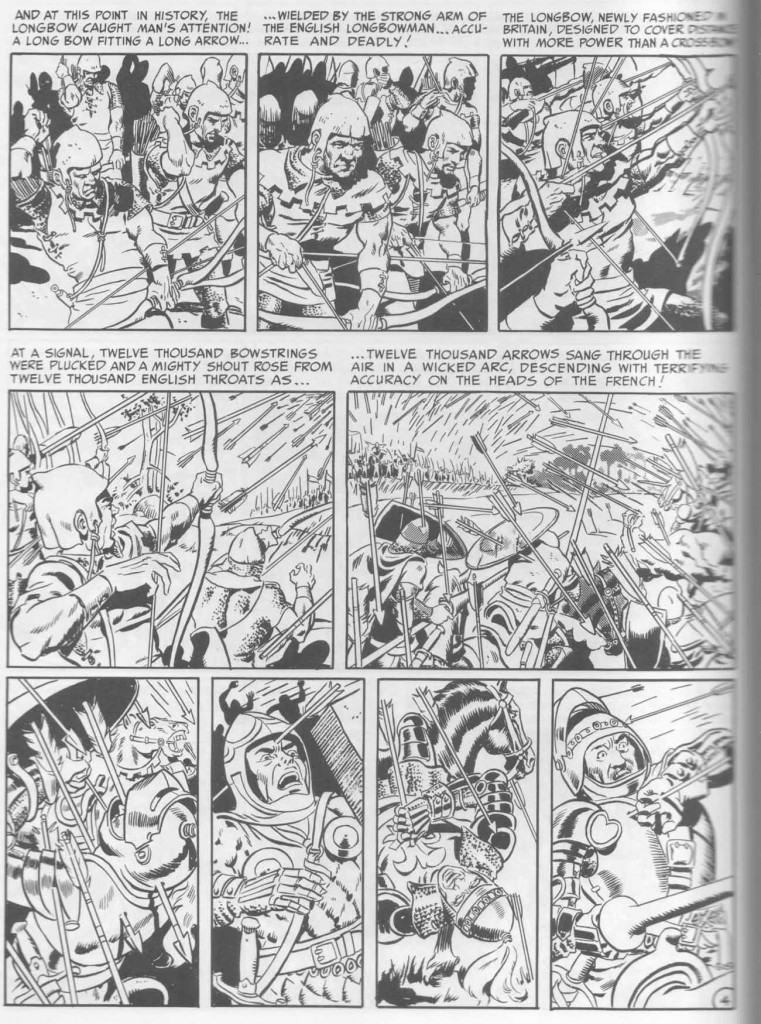

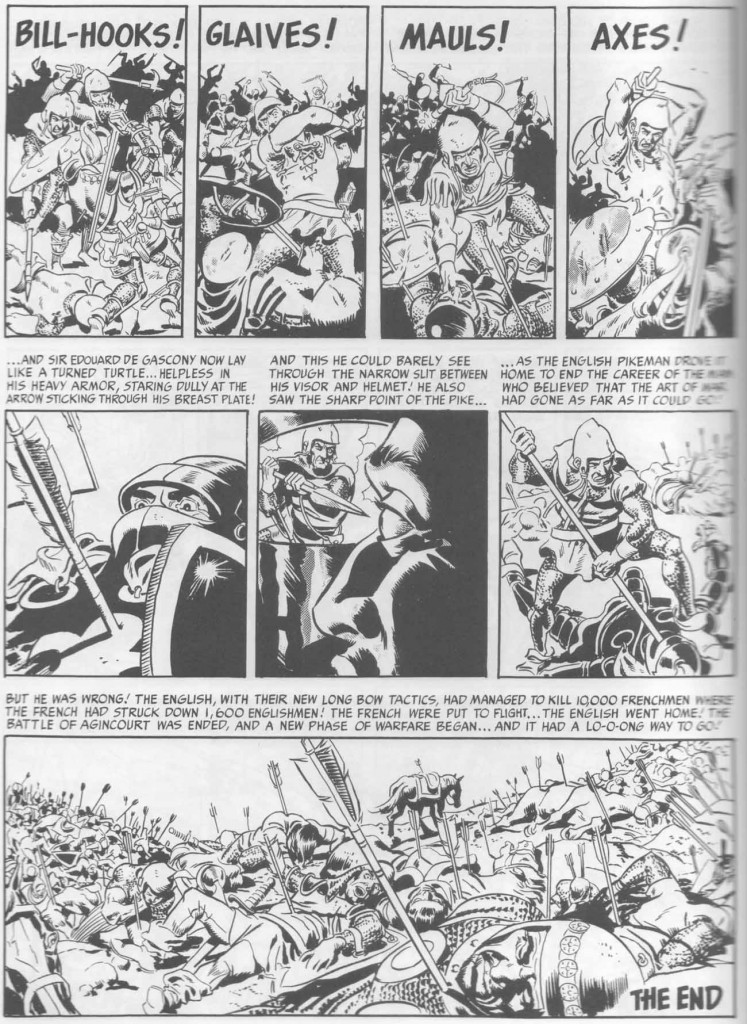

The French charged. They were mowed down by English arrows shot from formidable longbows. The very size of the French army hampered it from fighting.

The rout of the French was total. They lost some 5000 men in the massacre, against English losses of around 450. (Kurtzman cites respective losses of 10 000 versus 1600; my numbers reflect current consensus.)

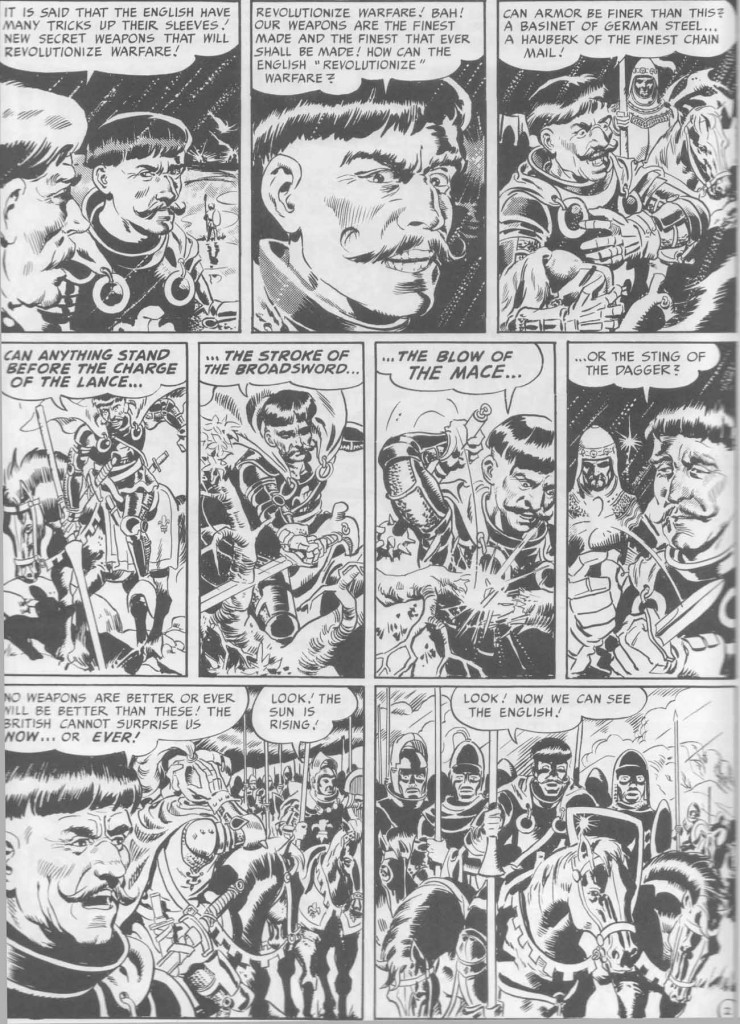

This time, no factual errors can be imputed to the comics story. But note the attitude expressed by the Frenchman on page 2, panel 2:

“Revolutionise warfare! Bah! Our weapons are the finest made and the finest that ever shall be made! How can the English “revolutionize” warfare?”

“No weapons are better or ever will be better than these! The British cannot surprise us NOW…or EVER!”

You guessed it, Kurtzman is setting up the poor hubristic schmuck for a piercingly nasty reality check:

And besides the knight-killing longbow, what are the terrible new English weapons?

BILL-HOOKS!

GLAIVES!

MAULS!

AXES!

Once again, new technology trumps old, right?

Highly improbable.

The French actually had more archers than the English at the battle; they simply weren’t deployed.

As for weapon technology, while the longbow was a devastating speciality of the Welsh and English, the French had a large company armed with crossbows—arguably the equal or superior of the longbow.

Bill-hooks, glaives, mauls and axes had all been known for centuries; the French certainly had them too.

No, the English king’s victory at Agincourt can best be ascribed to his superb leadership, and to disastrously bad leadership on the French side.

Are such distortions of history harmful? They certainly can be.

The attitude that high-tech will always have an invincible edge over low-tech in battle is a dangerous one to adopt, and though it were natural in Harvey Kurtzman’s 1950s, in 2010 it seems perilously naïve.

We have only to look at conflicts such as Vietnam or Afghanistan to see low-tech stymie or stop high-tech. What is the leading killer of American and Coalition troops in Iraq ? The I.E.D., or Improvised Explosive Device: a decidedly crude but effective remote-controlled bomb. The U.S.A.’s futuristic drone planes can do little against them.

At the time of “Light Brigade”‘s publication (1951), in the Korean war, the Chinese low-tech “mass infiltration” had succeeded against the UN troops where the North Koreans, true to their Soviet training, had failed for all their modern tanks and MIG jet fighters.

The writer Neil Gaiman once remarked that each popular genre carries expectations that its works are expected to satisfy. (Thus, a murder mystery will be solved, a superhero comic will feature fights, pornography will stimulate one’s genitals, and so on.)

Gaiman went on to say that one of the expectations for a war story is that someone learns a lesson. I’d disagree that this requirement is universal to war comics– what does Sergeant Fury ever learn?–, but it certainly holds true for Kurtzman’s war stories: each one illustrates an implicit homily; sometimes different stories advance different conclusions.

‘He that fights and runs away shall live to fight another day’ (“Pell’s Point!” TFT#28) contrasts with the need to stand your ground in the face of the enemy (“Weak Link!” TFT#24); “civilians can’t stay aloof from fighting” (“Wake!” TFT#30) versus “civilians should stay uninvolved” (“Choose Sides!” FC#9)

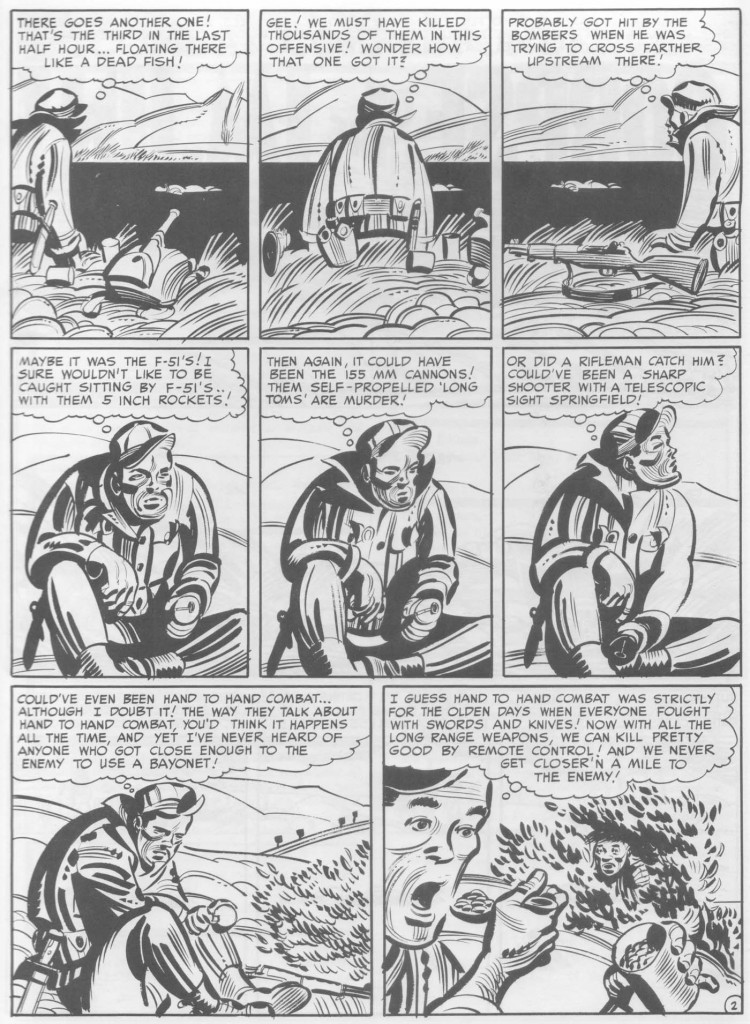

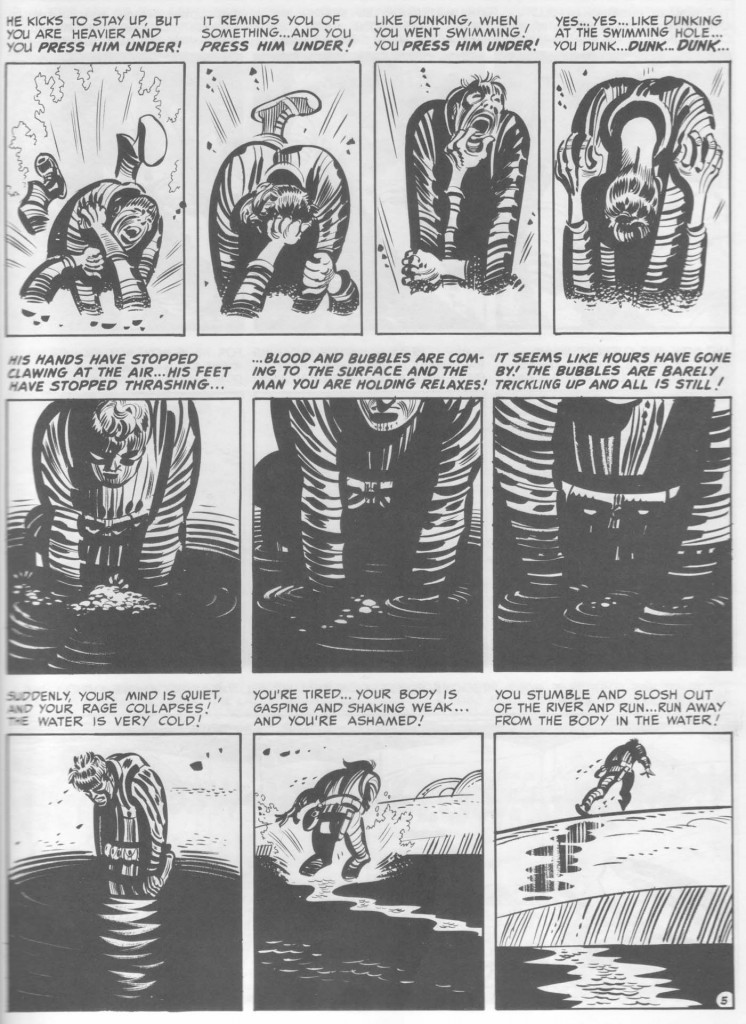

It’s an ongoing dialectic, thesis and antithesis. The antithesis to Kurtzman’s excessive (to my mind) faith in technology can be found in a tale that many consider to be his dramatic masterwork, ‘Corpse on the Imjin!’ (TFT#25), written and drawn by himself:  The young soldier in the above page muses on modern warfare:

The young soldier in the above page muses on modern warfare:

“I guess hand-to-hand combat was strictly for the olden days when everyone fought with swords and knives! Now with all the long range weapons, we can kill pretty good by remote control! And we never get closer’n a mile to the enemy!”

Of course, in the bushes nearby, is a hunger-crazed enemy deserter who is going to give our soldier an instant education.

They will both soon be grappling for their lives, unarmed, and the soldier is forced to kill his foe with his bare hands:  So much for technology!

So much for technology!

all artwork copyright EC

Many warm thanks to Ng Suat Tong for his practical help and wise advice, without which I could never have written this article.

—————————————————————————–

A very readable non-fiction account of the charge at Balaclava– the events leading up to it, and the aftermath– is Cecil Woodham-Smith’s The Reason Why.

For a superb fictional evocation of the charge of the Light Brigade, I recommend the novel Flashman at the Charge by George Macdonald Frasier.

The 1968 film The Charge of the Light Brigade, directed by Tony Richardson, is a superb and unflinching look at the horror and stupidity of war. A bonus for us cartooning fans are the jaw-dropping animations by Richard Williams that punctuate the film:

Victorian engraving come to life!

The text of Tennyson’s poem is here.

Jingoistic and war-glorifying, yes; but wow, what rhythmic power!

Agincourt, of course, was memorably the climax of Shakespeare’s Henry V. On film, one may prefer the Kenneth Branagh version of 1989 to Laurence Olivier’s earlier version– the Branagh movie conjures well the filth and horror of war.

Bernard Cornwell wrote a very good novel about the battle, Agincourt, told from the viewpoint of a common footsoldier.

I haven’t read it, but Noah Berlatsky recommends John Keegan’s book The Face of Battle, with a section on Agincourt.

And here is a link to the full artwork for “Massacre at Agincourt!”.

The map of the battle of Agincourt was released to the public domain by its author, “Andrei Nacu”, and published on en.wikipedia.org.

Thanks for this Alex. My knowledge of Kurtzman’s war comics is virtually non-existent, so it’s nice to learn a bit about them.

You mention “narrative tidiness” — I think this is one of the biggest difficulties in terms of representing war. It’s hard not to put in morals or narrative arcs, and doing so tends to rationalize or justify the experience of war even for supposedly anti-war writers (all quiet on the western front, for example, is much more ambivalent than its author probably intended.)

There have been some efforts to get around this; Catch 22 is I guess the most famous maybe, and Tobias Wolff’s vietnam memoir I remember doing a fairly good job in a more straightforward narrative vein. But it’s awfully hard to be convincingly anti-war in a pulp idiom, I think. (Though come to think of it Joe Haldeman’s Forever War and (following on from that) Alan Moore’s Halo Jones do pretty well.)

There is a certain hypocrisy involved, isn’t there? I remember the seventies war comics from DC would follow a thrilling tale of exciting violence with the solemn motto “Make war no more”.Sheesh!

BTW, it doesn’t come through in the article, but I’m actually a great admirer of the Kurtzman war stories. And what few inaccuracies he may have committed are nothing next to those of Robert Kanigher…who had Sgt Rock and Easy Company at the British retreat from Dunkirk…more than a year before America entered the second world war!

(Ah, Kanigher…he pops up everywhere, doesn’t he? Kind of HU’s official nemesis…)

I think the Balaclava fiasco is a textbook example of Clausewitz’s “fog of war” and its dangers.

I wouldn’t call it hypocrisy — more like a genre difficulty that its hard to overcome, even with the best will.

Kanigher is omnipresent!

I’d go with that, actually.

“It’s hard not to put in morals or narrative arcs, and doing so tends to rationalize or justify the experience of war even for supposedly anti-war writers.”

Could you expand on this? How does a narrative arc “rationalize or justify” war when the “best” anti-war novels suggest that war is meaningless, and that any progress is that which leads into the abyss?

As for your examples, The Forever War builds up too much reader fascination through its space travel mechanics and SF tropes. They’re metaphors but it creates a distance from the human element – art obscuring emotion. On the other hand, I last read it several years ago and I may have missed something which you didn’t. When last I read Halo Jones (around the time of its release), it didn’t strike me as particularly hard on war. It felt more like space opera/adventure story. I think All Quiet on the Western Front is far more successful than both of these at capturing futility and meaninglessness.

All Quiet has real problems with romanticizing war as essential reality; that is, the characters know the (ugly) truth that civilians don’t. But if the truth is only accessible to those who have fought, then that makes the experience of war more valuable, not less. This camaraderie of the front is emphasized and romanticized in similar ways. (I have an essay on this somewhere; maybe I’ll post it on the blog if it seems like folks are interested.)

Narrative is itself meaning, so a narrative about meaninglessness tends to undercut itself. That’s why Joseph Heller tried to disorder narrative in Catch 22 (with some effectiveness at least, I think.)

I read Forever War longer ago than you, so I may be giving it too much credit. Halo Jones is pretty hardcore by the end; sympathetic characters die meaninglessly, the war is empty, stupid, and grindingly horrible; the main character discovers she was personally complicit in horrific war crimes. It’s definitely strongly influenced by Moore’s anti-war stance.

Noah, have you seen the movie “Army of Shadows”? It’s not a combat movie — it’s about the French Resistance, but it’s compellingly anti-war. I haven’t read Halo Jones but I could see the description you give loosely applying to AoS too. I think it completely avoids the problem of romanticizing war as essential reality, if I understand what you mean by that, but it’s still narrative.

It’s from 1969 but didn’t get released in the US until 2006: Cahiers panned it for its politics after 1968 and American art houses took their cues from Cahiers.

One of my favorite war stories was written by Kanigher. It’s this one, superbly drawn by Alex Toth: http://tinyurl.com/3y56or8

Suat is right when he says that these war comics for children don’t give us a true feeling of the horrors of war: soldiers being killed by their comrades’ shattered body parts after an explosion and things like that. Tardi tries, but, in my opinion, he also suffered from the “trying to create potent stories with the tools of jokes” syndrome. His work is too cartoony… Even so I would say that, if we don’t count Otto Dix’s marvelous _Der Krieg_ (he’s part of my expanded comics field), he’s the one who goes farther in that direction.

“Massacre at Agincourt!” (_Two-Fisted Tales # 5 – # 22 was fake) and “Light Brigade!” don’t separate enough from history books for children (in which war is just military action) for my taste (historical truth being respected or not being irrelevant here). (I have the same problem with Crumb’s _Genesis_, but I’m not interested enough in that one to even discuss it…)

I find Kurtzman a far better artist than Severin, Wood, Davis, Craig. His solo stories are the better war stories in _Two-Fisted Tales_ and _Frontline Combat_ in my opinion. But, here again, I have another problem: allegory…

Oesterheld’s remain my favorite war stories because war is just in the background. What interests him are the people involved, their conflicts and how they deal with them. In Kurtzman’s better stories his little characters are just puppets to make a general point.

That’s, at least, what I remember: to be more accurate I should reread these comics and I don’t have the time to do so right now, sorry… Deleuze is waving his nails and calling me…

Easier to write/construct anti-war stories from lost wars, I imagine. Plenty of Viet Nam examples that work well….since Viet Nam doesn’t have the narrative arc (for America, anyway) that concludes with a “happy ending.”

Michael Herr’s _Dispatches_ is particularly good.

Tim O’Brien too, although I haven’t read Things They Carried in toto…

Halo Jones is, indeed, pretty hard on war…although that storyline is only part of the broader story. It isn’t until “book 3,” I guess where it comes into central play. Given that HJ was supposed to be 9 books long, it’s hard to say how central it might have been in the overall picture.

Haven’t seen it; I’ll try to check it out though.

My point about narrative isn’t absolute or anything; it’s just something you have to think about and deal with, I’d argue. Both Haldeman and Moore actually do various odd things with time in part to get around the way that narrative closure creates meaning, for example.

“All Quiet has real problems with romanticizing war as essential reality; that is, the characters know the (ugly) truth that civilians don’t. But if the truth is only accessible to those who have fought, then that makes the experience of war more valuable, not less.”

Does it really? Are there philosophical points made outwith the protagonist’s current theater of experience? Because if the “truth” he is apprised of and which you have expressed reservations about concern the nature of war, then I see little problem with this. There can be no doubt that the “experience of war” is valuable to all anti-war novels. How else would we know with absolute certainty that such an option is to be approached with great trepidation?

Isn’t Remarque’s book merely portraying the reality of what soldiers experienced on returning from the trenches. I think you might find similar descriptions in a number of WW1 novels (or in war poems like Wilfred Owen’s The Send-off which I presume is too romanticized for your taste) and history books though I will have to do some digging to be sure. Maybe I need to reread the book to see it with new eyes. Send me that article if you find it.

I think the greatest problem with seeing Halo Jones as an effective anti-war comic is its artifice and futuristic setting – the fascination which is attached to the setting obscures the human picture. Ian Gibson’s stylized and angular figures don’t help much either. It’s all very abstract and unemotional. I felt very little on reading it as a teenager and I expect even less now after I’ve read even more about events which are based in reality and which are much more terrible.

“All Quiet” seems to highlight a harsh truth about war, in its passage where Paul returns home to his family on leave: unless directly impacted by war, the civilians ‘back home’ don’t know the suffering and horror endured by soldiers– in fact, they don’t WANT to know.

Domingos, your judgment on the two stories I evoked strikes me as harsh but true. Really, when your format is a maximum of eight pages long, you would do better to focus on a single individual.

Kurtzman did this superbly (to my mind) in “Custer’s Last stand!” and “Alamo!”, particularly the latter. A major battle? For the poor bloody soldier involved (a 7th Cavalry trooper in ‘Custer’, a Mexican infantryman in ‘Alamo’), nothing was ‘major’ about these battles except the fear of dying.

Parting thought– Paul Fussell, a combat veteran of WWII and a historian of war-inspired literature, speculated about why WWI produced so much excellent poetry (Owens, Sassoon, etc) and why WWII did not.(For him, the great poet of the second world war was Anon, author of ‘The D-Day Dodgers’.)

His view was that the best poetic response to WW II was silence…

It is much like Wilfred Owens poems, sure. There’s a discourse of WWI memory. Saying it just shows the reality of war is the claim; however, that claim is made through the use of literary tropes which contain or are meant to demonstrate authenticity. The privileging of authenticity is I would argue the problem. There’s a big difference between the gothic reality of All Quiet (which, like gothic in general, is romanticized) and the reality of Tobias Wolff’s memoir, which is much more about boredom (and therefore less appealing.)

You seem in general to feel a sci-fi setting invalidates these kinds of narratives (if I understand you right.) I don’t think that’s the case; in a lot of ways I think the distancing can help offset some of the problems around authenticity. In any case, I found Halo Jones extremely moving (though obviously such assessments are subjective!)

Maybe I’ll run that war piece on Saturday or something, since you’re interested. It’s from college, so it may not be up to snuff — but what the hey. It’s my blog!

“All Quiet” is GOTHIC ?!?

Oh, really?

Absolutely. Isn’t that the one with the assault in the graveyard with the corpses blowing up all around them? I know it’s the one with the lice with the giant red crosses on their heads. The whole thing is pretty horror movie; both repulsed and obsessed by death.

It’s a long time for me; I read about 100 or more books on World War I when I was in high school, but I definitely remember reading about the gothic tropes of some WWI German fiction (Ernst Junger was another one.) You get a similar thing in a lot of war films; Full Metal Jacket absolutely glances, and more than glances, at horror tropes (with the guy who turns into an evil ogre figure/double especially — and especially especially in the context of homoeroticism.) It’s not exactly subtle.

Owen and Sassoon, in fact, have several poems about (or illustrating) how only those in the field/in the trenches know the “reality” of war…to the exclusion of all others (esp., for instance, women and politicians).

Noah: “You seem in general to feel a sci-fi setting invalidates these kinds of narratives (if I understand you right.) I don’t think that’s the case…”

I’m only talking about those two SF works but perhaps you could point me towards an SF work which you consider an excellent anti-war narrative. I’m sure there are a few (something by JG Ballard perhaps?). I also find that the problems with “authenticity” are smaller than those related to an indifference born of distance when such devices are used.

Anyway, just because of this discussion, I did a flip through the final section of Halo Jones. Have you read it recently? It’s very cartoony and some of the scenes are extremely forced, a combination of tropes from Vietnam and the American Indian wars. Certainly anti-war, just not especially worthy of praise in this day and age. A lot of the things which you find reprehensible about “authenticity” have simply been transferred into a SF setting with very little embellishment. And the SF setting is just (to paraphrase Mary Poppins) the sugar to help the medicine go down. As a result of its publication venue (2000 AD), there’s a lot of focus on getting the plot moving and on dramatic set-ups a la EC. Even the best scenes are overshadowed by haste and histrionics. Some of these stories would not look out of place in Marvel’s The ‘Nam and, yes, an EC comic.

I’m not a big Ballard fan. I like both Haldeman and Halo Jones though. I did read it relatively recently, and think it’s better done than you appear to. My review is here if you’re interested.

I read All Quiet like 4 times…which kind of isn’t ideal. It’s not that good, and certainly doesn’t hold up to that kind of rereading.

Not coming up with any fiction right at the moment, but John Keegan book, Face of Battle, is excellent. Paul Fussell’s “The Great War and Modern Memory” is also very fine. Of those WWI memoirs I read, Robert Graves’ “Goodbye to All That” was probably the best.

I’m very much looking forward to you guys discussing Mizuki Shigeru’s Onward Towards Our Noble Deaths (1972?) due this fall from D+Q.

Best,

That actually sounds really interesting; thanks for pointing it out.

Suat — maybe Slaughterhouse Five?

Slaughterhouse Five is not that great, is it? I find Vonnegut fairly annoying

The Lord of the Rings actually does some interesting stuff with genre and war. Obviously it’s into the glory of it…but there’s a lot of sadness and despair as well. Frodo’s shell shock is handled movingly, I thought.

It’s hard to recommend Ender’s Game.

A Canticle for Leibowitz is pretty good, though maybe not quite on point (nuclear holocaust rather than conventional war.) The bitterness is well done, and there are some genuinely creepy bits — the general despair in humankind comes through without romanticization. My memory of it is hazy, but I definitely think it’s superior to Slaughterhouse 5….

As far as movies with scenes of war or battle that manage not to glamorize it, I would like to suggest Chimes of Midnight, which has shots of fierce fighting and pageantry that swiftly give way to what is essentially animals rolling in the mud, attempting to kill each other to survive. Fabulous stuff, and not dissimilar to what I like so much about “Corpse on the Imjin”.

I last read Slaughterhouse Five when I was about 14, so I have no idea whether it’s great or not. Hence the question mark!

I’d forgotten A Canticle for Leibowitz, but I also don’t really remember whether it’s good. I don’t remember it being bad, though…

I tend to avoid war stories. They upset me. Army of Shadows was remarkably, exceptionally good – worth being emotionally overwhelmed for a day or so after. But usually it’s just the emotional overwhelmedness without the worth.

That’s what I like about you, Noah – you have the weirdest taste. How many people would choose Halo Jones over V for Vendetta, All Quiet & Slaughterhouse Five?

Then again, I’m in the Caro-club – which means I last read Slaughterhouse as a kid and was quite happy with it at the time. It could be a pretty “meh” as you indicate but I’ve just now decided to reread it. And Caro’s citation of Army of Shadows is going to make me pull out the Criterion DVD I bought 1-2 years back or so. She’s like the instant cure for procrastination.

Glad to be of assistance!

It really is worth it. Simone Signoret is incredible – it’s been 3+ years since I saw it and I can still summon her face in several scenes almost instantaneously.

I can’t decide if the Caro-club sounds like a smoky ’30s place with a grand piano and great dresses or one of those ’70s dives where the men all have too-long mustaches and polyester pants…

We are forgetting Joe Sacco, maybe?

As for films I like _Paths of Glory_, but not much else.

I’m going to guess that Noah hates/dislikes Paths of Glory since he’s ambivalent about Kubrick and doesn’t like hints of romanticization in depictions of war (even if they’re plausible; I mean the ending which I don’t mind personally).

I haven’t seen it!

I don’t like the bits of Joe Sacco I’ve seen, though. NPR-ready self-vaunting dreck. Grumble, grumble.

On Army of Shadows: I’ll say it’s not strictly an anti-war movie but by telling it’s tale without sentiment it does convey some raw truths about war. I suppose in that sense it fits the bill. Considerably better because of this than the movies by Spielberg and Eastwood on the subject of WW2 which I don’t ever want to watch again.

There’s an interview in the DVD pamphlet in which Melville calls it both tragedy and nostalgia. Apparently it was well received by the surviving resistance members who saw it. I see that Jog and Tucker have called it a “a deceptively old school patriotic war film, albeit one that explodes with modern trappings” at The Factual Opinion. They also seem to consider Inglourious Basterds more conceptually complicated. I think that’s a view Noah might appreciate if he watched the show.

Paths of Glory definitely. Other strong war films include Renoir’s La Grande illusion, Bergman’s Shame, and De Palma’s Casualties of War. I’d include The Deer Hunter, too, although its depiction of Vietnam is bullshit.

A fascinating and most enjoyable essay, Alex. For all the technical “authenticity” Kurtzman fussed over, I find the oversimplifying or outright distortion of historic events for the sake of narrative effectiveness to be a far worse failing.

It’s very stereotypically nerdlike: aficionados of “militariana” making a fuss over the incorrect placement of buttons on a uniform – like superhero fans griping that Robin’s tights were colored incorrectly – yet wholly missing the larger picture. That neat n’ tidy tales grossly distort the very nature of war.

—————-

Noah Berlatsky:

….My knowledge of Kurtzman’s war comics is virtually non-existent, so it’s nice to learn a bit about them…

…I don’t like the bits of Joe Sacco I’ve seen, though. NPR-ready self-vaunting dreck. Grumble, grumble.

—————–

Good grief; and you do comics criticism? That’s like a film critic who’s only seen snippets of Kubrick, doesn’t like the Ingmar Bergman he’s seen…

I detest NPR; as far as depicting the reality of war in its messy and horrendous complexity, lack of tidy endings or morals, no one has come close to Sacco. (And I’ve read Tardi’s “This Was the War of the Trenches.”) Sacco’s actually been dealing with real-life war since his early “Yahoo” days; one story dealing with the idea – and reality – of “victory through aerial bombing.” And who particularly focuses on civilians, those seldom-featured figures in war comics.

(The “Corpse on the Imjin!” line about “…Now with all the long range weapons, we can kill pretty good by remote control! And we never get closer’n a mile to the enemy!” reminds of one DC war comics story, where infantry soldiers repeatedly say that the artillery attacks and USAF bombing of an enemy-held town will “Soften ’em up!” Then at the end realize it still needs soldiers on the ground to wrest the town from the German troops through close-in fighting.)

——————

Alex Buchet:

The attitude that high-tech will always have an invincible edge over low-tech in battle is a dangerous one to adopt, and though it were natural in Harvey Kurtzman’s 1950s, in 2010 it seems dangerously naïve.

We have only to look at conflicts such as Vietnam or Afghanistan to see low-tech stymie or stop high-tech. What is the leading killer of American and allied troops in Iraq ? The I.E.D., or Improvised Explosive Device: a decidedly crude but effective bomb. The U.S.A.’s futuristic drone planes can do nothing against them.

——————-

My favorite example of this effect is when, during the Vietnam War, the Pentagon spent millions in developing an electronic device to sniff out the Viet Cong hiding in the jungle. Which the VC immediately stymied by hanging sacks of human feces from trees.

——————-

Ng Suat Tong says:

…perhaps you could point me towards an SF work which you consider an excellent anti-war narrative…

——————-

It’s satiric rather than grimly antiwar, but Harry Harrison’s 1965 “Bill the Galactic Hero” deliciously jabbed away at idealizing of conflict, recruiting’s glorifications. The Wikipedia entry for the book (I’ve not read the sequels) mentions, “Harrison reports having been approached by a Vietnam veteran who described Bill as ‘the only book that’s true about the military.’ ”

A review mentions how…

——————-

Bill is a big, dumb farm boy, minding his business on a distant world when he is shanghaied by a passing recruiting officer and his band of gleaming robots. Before you know it, Bill finds himself in a Catch-22 world of rules and regulations, where it’s almost impossible to get ahead and where the slightest infraction can earn you the enmity of your commanding officer. And if that officer happens to be Petty Chief Officer Deathwish Drang with his artificial two-inch canines, you might as well be dead.

——————-

http://www.sfsite.com/01b/bgh96.htm

(I believe the fangs sported by General Luiz Cannibal in “Halo Jones” were a definite nod to “Bill the Galactic Hero”…)

——————-

Noah Berlatsky:

You mention “narrative tidiness” — I think this is one of the biggest difficulties in terms of representing war. It’s hard not to put in morals or narrative arcs, and doing so tends to rationalize or justify the experience of war even for supposedly anti-war writers…

——————–

——————-

Ng Suat Tong:

Could you expand on this? How does a narrative arc “rationalize or justify” war when the “best” anti-war novels suggest that war is meaningless, and that any progress is that which leads into the abyss?

——————-

——————-

Noah Berlatsky:

…My point about narrative isn’t absolute or anything; it’s just something you have to think about and deal with, I’d argue. Both Haldeman and Moore actually do various odd things with time in part to get around the way that narrative closure creates meaning, for example.

——————

That phrase of “narrative closure creates meaning” neatly encapsulates what I was going to suggest.

——————-

Alex Buchet:

…Neil Gaiman once remarked that each popular genre carries expectations that its works are expected to satisfy. (Thus, a murder mystery will be solved, a superhero comic will feature fights, pornography will stimulate one’s genitals, and so on.)…

————–

And, a narrative arc and closure are – whether we get a happy ending or a tragic one – inherently satisfying to our basic expectations. Thus, even though the whole work may end grimly, there’s a sense of rightness when a story is neatly tied off at the end.

“That’s like a film critic who’s only seen snippets of Kubrick, doesn’t like the Ingmar Bergman he’s seen…”

Well, I do film criticism too on occasion, and while I’ve seen some Kubrick and Bergman, I’m not especially interested in either. So there you go — I am ignorant across multiple media.

That story about Sacco’s mom being attacked by a German airplane is quite good. There are only two things that I don’t like much in Sacco’s work: his portraits (he’s better with landscapes; I suppose that it’s clear enough by now that I’m not crazy about using cartoony drawings to depict serious matters, Chris Ware excepted); his unbalanced portrait of the events. As he told me once: he has an opinion, but I view art as a kaleidoscopic view on politics and life. His _Footnotes in Gaza_ is in my “to read” pile. The problem is that, right now, I’m reading _Rip Kirby_ vol. 1. Oy!… (I don’t know how to say that in Arab.) I blame the silly season…

@ Mike Hunter:

Glad you enjoyed it, Mike!

I’m a huge fan of “Bill, the Galactic Hero”. May I also mention that it’s one of the funniest novels I’ve ever read.

Harlan Ellison’s short story “Soldier” is a good example of war’s horror expressed in science-fiction terms. Likewise Ursula Le Guin’s “The Word for World is Forest”.

A TCJ Message Board thread about a pretty damn excellent war comic:

“Crécy,” by Warren Ellis and Raulo Caceres

http://archives.tcj.com/messboard/viewtopic.php?p=35965&sid=6021e07a29bb1cfe704fcea792dcb374

I agree wholeheartedly.

I read Slaughterhouse 5 recently and found it to be pretty “meh” to use Suat’s words. In fact, I backed out of teaching it. It has a few funny bits, but I would hardly call it a great war story.

Ian McEwan’s Atonement has some great writing around the Battle of Dunkirk. And also does some tricky things with narrative at the end to circumvent any sense of tight closure.

The movie, unsurprisingly, is not as good.

Pat Barker’s WWI books are also pretty good (at least the first one is…

I am surprised not to see mention of John Benson’s article “Is War Hell” from Panels #2, 1981, where he makes the case that as Kurtzman increasingly dealt directly with military personnel to do the necessary research for his war books, his work became more sympathetic to, or at least less critical of, the viewpoint of the military, for a variety of reasons, something also seen in the more recent imbedded press.

Barker’s whole series is pretty good, if I remember. I think it actually got better as it went along….

Haven’t read those Barker books in ages but I think The Ghost Road may have been the best of the trilogy. Didn’t get as much out of Atonement.

I wouldn’t disagree with Eric on Slaughterhouse 5 now that I’ve reread the book. It’s certainly anti-war but not in a way which is especially overt until the effects of the Dresden firestorm are described towards the close of the novel. Simple but not unskillful prose appealing less to the emotions than to the groundswell of feeling at the time emanating from Vietnam and the Cold War. It’s starting to show its age a bit and gets a bit didactic towards its close though the final pages are quite satisfying. I think it will be remembered for its central idea surrounding time and freewill/determinism, and the small prose section which was later emulated by Martin Amis in Time’s Arrow. Interestingly enough, it also quotes from The Destruction of Dresden by David Irving (of the famous libel suit where he sued Deborah Lipstadt for labeling him a Holocaust Denier and Nazi sympathizer). An unimportant point at the time now made large. The Dresden mortality figures have since been revised downwards but remains an important issue.

I’ll see if I can find that John Benson article James mentions.

That Keegan book Noah mentioned is well done. I’ve read several of his military histories which are quite detailed. He has a very definite agenda he is pushing, but he is great at marshaling his facts in a such a way that his POV seems quite reasonable.

I actually was just rereading A Canticle to Leibowitz and left my copy in a taxi about two-thirds read last night. Sigh. Miller spent a lot of time working the prose for every purple word, but I was still enjoying it. Seems to owe a lot to the Asimov Foundation series, a least in its scope and delivery (although not in the overwrought prose department.)

Ender’s Game would qualify for what you’re looking for when taken in the grand scheme, I suppose, but my remembrance is that the series ended up humanizing just about every decision made by just about every character “There is no wrong or right” kind of thing. More of that in the later books, if I remember…

oh yeah,

Never a big fan of Slaughterhouse. I much preferred Sirens of Titan. Now THAT is pessimism.

Who is Sirens of Titan by?

Asimov is pretty much just puzzles; sci-fi’s Agatha Christie (which is actually fine as far as I’m concerned.) Miller has a definite agenda; he’s trying for art (for what that’s worth.)

Interesting views here.

I’ve just re-read my own article and find it a bit disturbing re: my mindset. You’d never think I was discussing war rather than a tea party. Too much of the aesthetic, in the Kierkegaardian sense…

BTW for those of you kind enough to have read my Tintin posts, these have been updated with new art& photos.

I’ve thanked Ng Suat Tong in the article, and that’s because a) he came through with some crucial art for me, a stranger, and b) he gave me some well-observed critiques that spurred me to sharpen the article a bit.

Thanks, doctor.

James:

” I am surprised not to see mention of John Benson’s article “Is War Hell” from Panels #2, 1981, where he makes the case that as Kurtzman increasingly dealt directly with military personnel to do the necessary research for his war books, his work became more sympathetic to, or at least less critical of, the viewpoint of the military, for a variety of reasons, something also seen in the more recent imbedded press.”

The two stories discussed here — “Light Brigade!” and “Massacre at Agincourt!”– come in quite early, and dealt with non-American, historically remote events.

Still, one can be suspicious of Kurtzman’s sources. He was proud of calling on the expertise of the popular Civil War historian Fletcher Pratt; but Kurtzman’s assistant, Jerry de Fuccio (who did much of the research legwork) was disgusted with Pratt, whom he considered a fake.(Aside: Pratt was a wonderful fantasy author.)

By his own account, Kurtzman had never been much of a history buff before he started TFT, unlike George Evans or John Severin.

Sirens of Titan is another Vonnegut. I think of it as more broadly philosophical than specifically anti-war, but indeed there is an interplanetary war.

The first edition cover is great.

Pratt did those Incomplete Enchanter books with L. Sprague de Camp, right? Good lord, I haven’t thought of those in a decade, probably….

“The two stories discussed here — “Light Brigade!” and “Massacre at Agincourt!”– come in quite early, and dealt with non-American, historically remote events.”

Okay, I was thinking more of where you mention Kurtzman’s technophilia…perhaps that was more a byproduct of researching the actual machinery of war with the people who implement its use.

I know Noah will be appalled, but I remember Mailer’s The Naked and the Dead as a pretty great war book. Of course, I read it probably 20 years ago–so I can’t be blamed if I’m leading someone astray.

I hate your reply system. It erases my comments if I forget to entet the ‘CAPTCHA’ code.

Anyhow, I think you’re being hard on Harvey because he bothered trying at all. It’s hard to name a war story that didn’t make significant errors to help the story along.

In the movie Black Hawk Down the troops all say they’re fighting for their fellow troops, not for the Sudanese. In the original book, they all impress the author with their enthusiasm in helping the Sudanese, and are outraged when they’re withdrawn because they still believe in the cause. Obviously the producers opposed ‘nation-building.’

Or try Googling “saving private ryan inaccuracies”. You’ll got lots of links. On the pedantic side, German troops didn’t get crew cuts or shave their heads. They were required to keep the hair on top slicked back to cushion the helmet. More significantly, the troops wandering the front don’t meet groups of UK soldiers. That’s because it’s a movie about America, not France or Britain or Europe at all.

Crap. I’m sorry Gene. The captcha is there because the spam was completely out of control.

One way to get around the problem somewhat is to create an account on the site (there’s a button up there on the top right.) If you’re signed in, a lot of the captcha regime is bypassed.

Tho’ having had troubles with Captcha (resolved once Noah kindly explained including a lot of links makes it block the post), I’ve not lost any posts ’cause I write ’em “off to the side” in TextEdit* prior to pasting them in the “Leave a Reply” window…

* Which has the added bonus of being able to look at my horse-choking chunks of prose – and shuffle paragraphs around and such – in a bigger space that that lil’ window.

I was comparing Leibowitz to the Foundation books more in their scope, I suppose. “And then three centuries later…”

I enjoyed the Naked and the Dead as well, although it’s been many many tears since I read it. Norman always struck me as the Jello Biafra of literature (even if theeir politics were very different.

“There’s always room for Norman!” would have made a for fantastic campaign ad…

Ballard’s “Empire of the Sun” has an interesting take on war.

Gene Ha,if I’m a bit hard on Kurtzman (or on Hergé in my Tintin posts) it’s out of love; love must never be uncritical.

I’m a big fan of your work, of course. And I’d like to see your artistic take on a realistic war story!

Hey, I made it to Journalista! Maybe Dirk’s forgiven me!

(Though “forgotten” is the more likely past participle.)

“I don’t like the bits of Joe Sacco I’ve seen, though. NPR-ready self-vaunting dreck. Grumble, grumble.”

Whoa. NPR would never be as critical of Israel as Sacco is.

Plus…Sacco is doing something on a level hardly anyone else can do…taking testimony from people and re-staging it in comics form in this meticulous way that’s both accurate and wrenching.

I’d love to read a tortured defense from you on why Sacco isn’t good, as it would involve lots of intense leaps of faith on your part.

Well…it would require me to read more Joe Sacco than I have any desire to do, so I think I’m probably going to disappoint you, alas.

I don’t like Noam Chomsky either, if that helps.

They’re not at all similar, Noah.

Pingback: Scary war | Comics Madness