Conception/ Sugarcane Island/The Cave of Time

“What is time?” you ask.

The oracle is silent for a moment, but then answers in a firm voice, “Time is what keeps everything from happening at once.”

“When did time start?” you ask. “And when will it end?”

“Would you like to see?”

You gulp in amazement. “Sure.”

“What then- the beginning, or the end?”

– Edward Packard, Return to the Cave of Time, 1985

He’s told the story many times over the past forty years, and so the words come quickly and easily, spilling out over the gulf between the two of us. In this story it is 1969 and he is the father, and the children are his children, eager for a gripping bedtime narrative. And all Edward Packard has is Pete, washed ashore on a deserted island. And so the father asks the children, “What do you think Pete should do?”

With the power of hindsight we can find some precedents to the Choose Your Own Adventure, forked-path fiction format. But when the concept first hit Edward Packard, it was like a bolt of lightning.

It would have a similar effect on his audience.

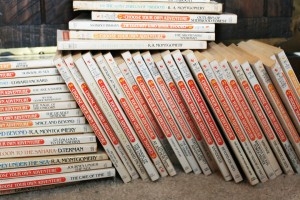

But his ultimate audience was not as immediately accessible as his biological children. Packard wrote the manuscript for his first book in the format, Sugarcane Island, in 1969 and 1970, and had an agent shop it around for years. “They all turned it down- they didn’t see the potential.” So he shelved the book, the whole concept. Several years later Packard saw an article about a start-up publisher named Vermont Crossroads Press, co-owned by one Ray (R.A.) Montgomery. Encouraged by the article, Packard contacted Montgomery and ultimately struck a deal with him, and in 1976 Sugarcane Island finally saw print, as the first in what was intended as a series of books entitled “The Adventures of You.” Montgomery followed up Packard’s book with a manuscript of his own, “Journey Under the Sea.”

Packard, frustrated with the lack of marketing muscle behind the releases, shopped around his concept and some new manuscripts and was eventually able to secure himself a deal with the J.B. Lippincott company. But unbeknownst to Packard, Montgomery and his newly acquired agent were working on a deal of their own with a much bigger company- Bantam Books. “Bantam decided that half of the books would be written or subcontracted through me and half of the books through Ray Montgomery,” Packard told me in a phone interview, almost thirty years after the deal finally went down. “Ray and his agent were really the ones who set it up. I was brought in because I’d started the whole thing.”

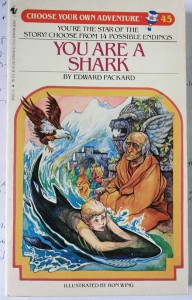

Youth/You are a Shark/Secret of the Ninja

There are no stars or suns or moons or wisps of light; not a breath of air; no sound; no smell or taste; no up or down or sideways; no motion; no feeling; nothing but silence. Suddenly there’s a point of light so brilliant, it feels like pins driven into your eyeballs! Even before you can blink, the light expands into a million lightning bolts radiating in all directions. Your eyes shut, but the light is still painfully bright. As you move your hands to cover your eyes you scream- but no sound comes.

– Edward Packard, Return to the Cave of Time, 1985

In the summer of 1988 my family moved across Orlando to a new home in a new neighborhood. When I entered third grade a few months later, it was with more than a little anxiety- I didn’t have any friends, didn’t know the school or the neighborhood at all. But I soon found compatriots, including a sandy-haired boy named Chris M., who would end up being my best friend for the rest of elementary school. And Chris had an inheritance.

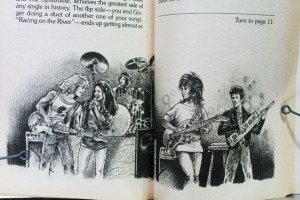

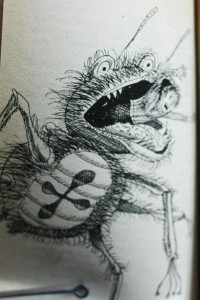

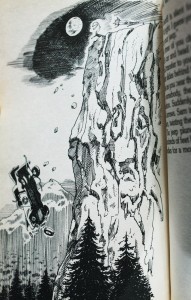

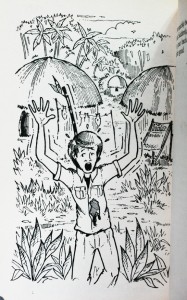

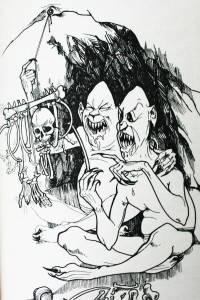

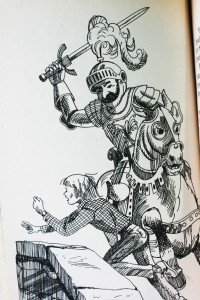

The books were a gift to him from his older sister’s boyfriend- a box full of Choose Your Own Adventures from a few years earlier. We poured over them, relishing the illustrations, the variety of settings and the sometimes lurid titles and subject matter. But what we loved most was the central, binding concept- the branching paths. The feeling it gave of inhabiting someone else’s skin, of living a new situation and being able to explore it in relative safety.

It was a kind of mania for us. The books were still coming out, and we bought as many as we could get our hands on. When we’d have sleepovers we’d pool our books together into one big collection, in chronological order of course, and talk about the missing books, what they might be like, and brag about how big our joint collection would eventually be when we were roommates in college together. Eventually we found that the earlier books were readily available on the cheap at garage sales and second hand stores of all types, and so our collections continued to grow.

All this emphasis on collection might imply that we didn’t read them- we did- we even had strong opinions about the book’s authors. (Edward Packard’s books, we deemed, were the most “fair”, and internally consistent, and often the most fun as well. Although we often were drawn to the concepts and themes of R.A. Montgomery books, we were put off by the lack of narrative logic and internal consistency, and what we saw as didactic, judgmental and sometimes capricious results from each choice.)

So I loved the reading. But the aspects of collectability were what fueled the mania. Firstly, they were numbered, which meant that after having acquired a handful gaps started to appear. Secondly, the books by various authors were often indirectly related to each other, or sometimes even direct sequels. The small connections from book to book served to heighten my interest in obtaining the other books.

Chris and I were obsessed enough with the format that we produced several Choose Your Own Adventure-format books of our own over the next two school years, including such classics as Escape From School, Math Escapes, More Escape From School, Gut Squisher, Save the Big Dudes, and a revised version of Math Escapes, with added violent behavior.

Rereading the particular books that obsessed us as children, it’s not hard to see what fascinated us. For more than a decade Edward Packard was one of the most innovative writers working in children’s fiction. He found the perfect formula in his first book, and so he could spend the next several years breaking, manipulating and stretching it.

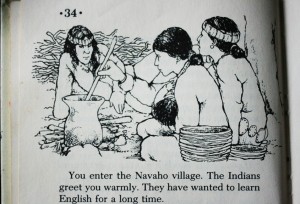

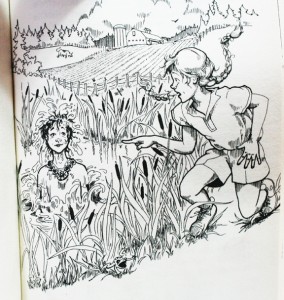

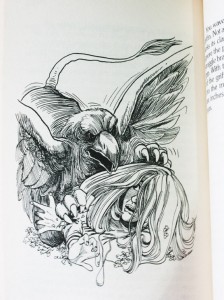

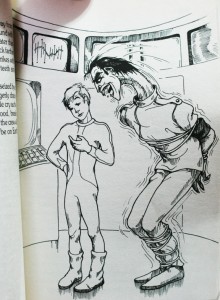

For Packard the formula wasn’t just the concept of branching path fiction– it was also the emphasis on you, the reader, the traditionally robust role of protagonist making way for the ego of the audience to fill in the gaps. This intention was often undercut by the Bantam illustration concept, which more often than not represented the protagonist as a ten-to-fifteen-year-old white boy. In rare instances this tendency was reversed , such as many of the female-protagonist (or even gender-unidentifiable) fantasy-themed books (Outlaws of Sherwood Forest, Mystery of the Secret Room, and the Enchanted Kingdom, all written by Ellen Kushner and beautifully illustrated by Judith Mitchell).

- “Mystery of the Secret Room” written by Ellen Kushner and illustrated by Judith Mitchell

I disagree with Packard as to the importance of the empty vessel– I don’t really believe such a thing is possible, even without illustrations. If the author is doing her job creating an environment and situation for you to explore, a natural result will be a character, even if it’s a character created solely by inference. Additionally, even as a younger reader I was very aware of which “characters” I liked and identified with, and how this changed my interaction with the book. I remember as a young boy finding the stories in which “you” were represented as a female strangely compelling, and finding myself drawn to the images of the female protagonists, studying them, trying to read their intentions and motives.

In the very early books, Packard himself deviates from this empty vessel prescription, and this makes for some of the more varied books in the series. You can sense him playing with the formula. In “Your Code Name is Jonah” you are a C.I.A agent, in “Who Killed Harlowe Thrombey?” a detective, two jobs not typically held by ten-year-olds. Perhaps a result of the wider variety of protagonist roles, these early books seemed a lot more off-the-rails and experimental than many of the later ones.

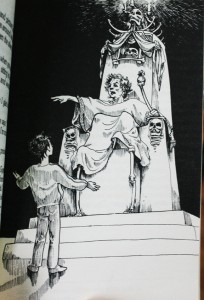

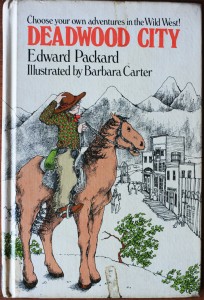

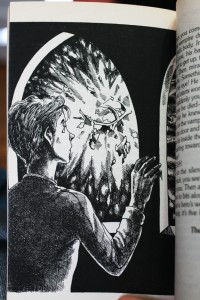

Packard wrote a lot of books, and not all of them are classics. A great deal of them are simply his treatments of standard adventure fare (Deadwood City, Survival at Sea, Sugarcane Island). And then… there are the few books of his that defy categorization. How would you describe “You are a Shark” to someone that’s never read it? It’s at once almost idiotically simple and yet profound and strangely moving- you visit the ruins of a temple in Nepal and enter, despite knowing you shouldn’t. And you find an impossibly old man inside the temple, who stares straight ahead, gazing into space, as you feel a flash of panic, and slide helplessly to the floor.

Though your body is alive your spirit has moved on to the body of another being. You move over and over again against your will, from animal to animal, while your body slowly perishes. For my third grade self, this was deeply moving stuff.

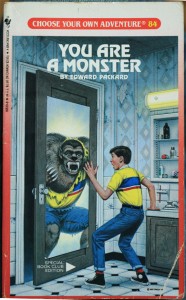

Adolescence/You are a Monster/ You are a Superstar

Pain. That’s the worst part of it. You can hear your bones cracking as you grow. Your muscles are growing too. They ache as they stretch to keep up with your bones- especially your arm bones, which are lengthening and thickening the most. Your skin is expanding, trying to cover your widening body surface. Sometimes it’s stretched so thin, you’re afraid it’ll split, but it always seems to cover.

– Edward Packard, You are a Monster, 1988

In those fevered two years of Choose Your Own Adventure obsession, I had no way of knowing that the best creative years for the series were already past. With more than eighty books already out, the past itself seemed infinitely rich, and so if I saw the signs I didn’t understand them. Eight years in the series had settled into a comfortable formula- easily explicable concept, punchy title, early dump of the author’s research in the setup to the story, and a decreasing amount and variety of choices and endings. Packard told me, at least in his case, that this was largely “a trade-off,” but it “wasn’t deliberate. I tended to want to expand the plot more, to try to make it richer, and the more a particular storyline gets involved, the less you want to branch it off.” Page count staying the same, the functional result of this was fewer choices, fewer random deaths, and less of the metaphysical wackiness that defined the books in opposition to other adventure books of the time.

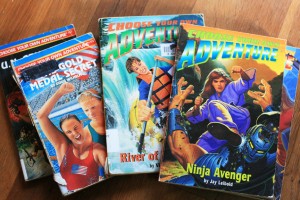

From an aesthetic standpoint, the books also finally made the transition to the eighties, with bright gradient backgrounds and hideous photo-realistic paintings on each cover. Although many of the excellent pen and ink interior illustrators managed to hang on for a while longer, they were gradually replaced by heavily-photo-referenced, toned pencil illustrations that completed the aesthetic transformation.

As for my interest in the books, and my friendship with Chris, both were long gone. Choose Your Own Adventure survived them both, in publication, if not in spirit.

Even as I moved through middle school I still found places to get my fix of interactive fiction. In sixth gradel I finally acquired a Nintendo, followed a year or two later by an SNES, and I discovered in short order a whole new realm of interactive fiction, namely the Japanese console-based role playing game. I would have become disinterested in the books eventually anyway, as they were aimed at fourth to sixth graders- but having a viable substitute certainly helped accelerate the process. Strange rumblings were happening at school too, every time we visited the computer lab. The school had replaced their Apple IIGS lab with an entire room of Macs, all of which came preloaded with a piece of software called Hypercard that felt strangely familiar to many of the students who used it. We were encouraged to build our own stories- draw a picture, have some text, and have some picture or text element that could be clicked through to advance the story. And from there the cards could branch out into many different directions.

I didn’t need to make the direct connection myself- our teacher pointed it out to us the first day we used it. “We’re going to make stories, like Choose Your Own Adventures. You guys can draw and write your own stories, and we’ll make logic trees, little maps, to keep track of the whole thing and make sure you don’t leave any loose ends.” (although Hypercard itself has been long forgotten, many more people seem to remember Myst, once the biggest-selling PC game of all time. Myst was a series of Hypercard stacks.)

It took me several months of computer lab time, but by the end of sixth grade, my one and only Hypercard creation, “Revenge of Abraham Lincoln” was complete.

Another year later and I had my first experience with the Internet. Another year after that and the web was on the horizon. Edward Packard, Apple and a vengeful clone of Abraham Lincoln had successfully prepared me to embrace the hypertext environment.

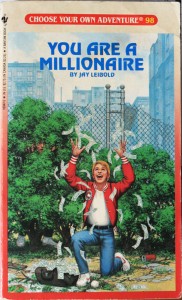

Adulthood/”The Worst Day of Your Life”/”You Are a Millionaire”

You are a decider,” she says. “Because you are from a primitive culture you do not understand that constant pleasure is superior to freedom of choice- though that should be obvious to anyone.”

– Edward Packard, Return to the Cave of Time, 1986

In 1998 Chris and I both graduated high school, the same year that Bantam ceased ordering new books from Packard and Montgomery, effectively ending the CYOA series. Was it part of the natural cycle of the market, or had the need for interactive fiction been satisfied by increasingly complex story-based console role playing games? Or had CYOA been done in by some factor much more mundane, like the continual paper price hikes of the mid to late nineties? I never saw the books at the time, but I’ve read some of the nineties books recently, and there is a feeling of desperation in the air- too many concepts that seem to be chasing trends or rehashing past successes, and a drastic (and aesthetically disastrous) mid-series visual makeover.

Before our graduation Chris and I had a brief reunion, worked on a comic together in our Physics class, and even kicked around the idea of writing some more interactive fiction. Sadly for us, we never got farther than a list of rather promising titles, before we were waylaid by life, girls, and more bitterness towards each other. (for the curious, the prospective titles were- “You are Homeless,” “More Math Escapes” and “You are a Teenage Girl.”)

Edward Packard and his former business partner R.A. Montgomery had a falling out of their own, one that has indirectly led to the odd state of the Choose Your Own trademark today. Currently the CYOA trademark is owned by Chooseco, which is in turn owned by one R.A. Montgomery, prolific writer of mediocre children’s fiction. The consequence of this is that the brand itself no longer features any work by the originator of the concept the brand is based on- no Edward Packard books will ever again be issued under the CYOA moniker.

And yet- we live in the future, and in the future nothing is dead forever. And so the trademark-less Edward Packard has teamed up with Simon and Schuster to re-imagine some of his CYOA books as iphone apps, under the new mark U-Ventures. And so time marches on.

As for the books themselves, it’s still possible to pick them up at rummage sales, book stores and ebay for pennies on the dollar, and the first sixty or so in the series, in addition to being the best, also happen to be the easiest to find. If you’ve never read a CYOA and would like to do so, or if, like me, you were obsessed as a child and now find yourself curious again, may I be so bold as to recommend a few titles for you?

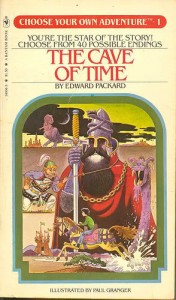

- Cave of Time (1)- Edward Packard- Not an excellent book, but very interesting to see how expansive the concept was from the very beginning. Long before a certain hot tub made time travel much more convenient, you wander through a cave in which every corridor leads to a different era.

- Your Code Name is Jonah (6)- Edward Packard- I seem to have a soft spot for Cold War political thrillers involving secret messages embedded in whale song.

- Hyperspace (21)- Edward Packard- Off-the-wall metaphysical gamesmanship meets buckets of pseudoscience, and what emerges is delightful, eccentric gobbledygook.

- Supercomputer (39)- Edward Packard- Has the distinction of being one of the goofiest books about technology written in the eighties, in an era not exactly known for its skepticism about technology. Fascinating, fun tangents into world politics and theories of wealth and happiness.

- You are a Shark (45)- Edward Packard- Reincarnation and bloodletting in an ancient temple in Napal. See above.

- Outlaws of Sherwood Forest (47)- Ellen Kushner. Guess what it’s about? More beautiful illustrations by Judith Mitchell.

- Return to the Cave of Time (50)- Edward Packard- A mess of adventure, theory and possibility.

- Magic of the Unicorn (51)- Deborah Lerme Goodman- Fun fantasy with nice illustrations by Ron Wing

- Enchanted Kingdom (56)- Ellen Kushner- Fun funny faerie adventures with sometimes brutal endings. Beautiful illustrations by Judith Mitchell.

- Mystery of the Secret Room (63)- Ellen Kushner. Two boxes and a mess of trouble. More beautiful illustrations by Judith Mitchell.

- The Worst Day of Your Life (100)- Edward Packard- An extreme, and extremely raucous, adventure book that also happens to be a meditation on the nature of disaster. A fine return to form for Packard.

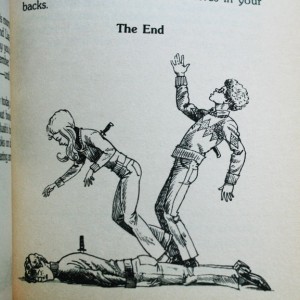

The End

The End

The End

The End

The End

The End

The End

The End

The End

The End

The End

The End

The End

The End

The End

The End

The End

“There’s not one perfect path. Usually there’s a whole spectrum of outcomes, of adventures. The idea is to try to mirror life in a way, all the possibilities of life. It isn’t either you get a pot of gold or you die. [There are] all kinds of things in between.”

-Edward Packard, interview, 2010

[special thanks to Edward Packard for his kindness and consideration. illustrators at the end, from top to bottom- 1-3 by Paul Granger, a.k.a. Don Hedin; 4 by Ted Enik; 5 by Anthony Kramer; 6 by Judith Mitchell; 7 by Paul Granger, a.k.a. Don Hedin; 8 by Ron Wing; 9-10 by Judith Mitchell; 11-13 by Paul Granger a.k.a. Don Hedin; 14 by Ted Enik; 15 by Paul Granger a.k.a. Don Hedin; and lastly, 16 by Judith Mitchell.]

I like this examination of a past obsession. I was too old for this series of books, but I can see their appeal…

There were similar books produced in France, reprints but also originals.

In England there was a very funny ‘You are Maggie Thatcher” CYOA-type comic drawn by the great Hunt Emerson!

Alex,

It’s really hard for me to let go of things from my past. I probably didn’t touch a CYOA for, I dunno, ten or twelve years, but then I picked one up at a bookstore and I was filled with this flood of memories and feelings. A strange sensation. My wife read over a draft of this article a few days ago and her first response was “you’re an old man, man.” Not yet thirty one and already old and nostalgic…

And does this translate into an interest in interactive comics like Jason Shiga’s “Meanwhile”? How did you find that book? The interactive/adventure game genre seems to be dying out but got a shot in the arm this year in the form of “Heavy Rain” – any interest in that?

I remember reading a bunch of these as a kid. They were like a poor man’s role-playing game to me.

My favorite author Raymond Queneau, make a proto-form of these (in the 60’s I think):

http://www.thing.de/projekte/7:9%23/queneau_1.html

Suat,

I’m embarrassed to say I haven’t read “Meanwhile” yet- when I heard about it (maybe a year or two ago?) I was really irritated that someone had beaten me to the punch. So it’s possible I’ll never read it, just in case I decide to do something similar in the future, although I’d probably enjoy it if I did. As far as Heavy Rain, I haven’t played it- I haven’t played a video game made after 2000. Not some moral stand or anything, just less time and less brain flexibility- most games seem to have “3-d” components and my controlling abilities never evolved past the side-scrolling or top down variety. I’ve always seen Japanese console RPGs (Chrono Trigger/Cross, Final Fantasy, Dragon Quest etc) as the closest thing to CYOAs, because of the emphasis on story, setting and narrative, although the choices and ability to affect game narrative are usually pretty limited.

I think making a very dense CYOA-style branching path video game is difficult for the same reasons that making a comic or movie of the same would be difficult- each split in the path diverts the resources of the author too, into channels that the reader might not even explore. So the payback for the multiple paths might be judged to be “less than” the resources (time, money, whatever) required to produce the multiple paths.

Derik- I could never find people to play RPGs with me that I could trust to not also be crazy. Also, thanks for the link! It looks really interesting. I’m aware of some earlier forms of branching path writing, including medical textbook “simulations” to help train doctors for different situations- but arguing about the beginning of it seemed out of the scope of this already-too-long article.

I’ve always wondered if the CYOA writers were familiar with, or influenced by Borges’ “Garden of Forking Paths” story. As usual with Borges, the concept is limned, but he leaves it to the Packard’s and Montgomery’s (and Julio Cortazar’s) of the world to actually do it. Cortazar’s Hopscotch is a cool formal experiment, but is nowhere near as fun as “My Codename is Jonah”…

Eric,

Obviously that’s where I got my title for the piece, but no, as far as I can tell, it wasn’t a direct influence. The main early-development stuff (Oulipou writers, Borges, training text books, and the Tracker series in Britain) can’t be directly traced back/linked to Edward Packard. So maybe it was just in the air, a concept whose time had come.

Some people have made even earlier claims, citing these linked, super-indexed versions of the Torah. Interesting to discuss, anyway, but probably can be as frustrating as the “first comic” argument (Toffler, of course. :) )

All you say is true but as far as graphics intensive games are concerned, “Heavy Rain” is a pretty impressive achievement. While there’s still a lot of work to be done to advance the genre, I would say that it’s one of the rare times that interactivity does actually improve the experience. I suspect there may be a lot more dead ends and forks in it than your average CYOA book. A huge step up from the last game with similar ambitions, the Blade Runner adventure game. You should give it a try if you own a PS3, maybe rent the game. The Japanese RPGs you list are incredibly rigid compared to “Heavy Rain” and not half as creepy. I’m being purposely vague here just in case you do decide to sample it.

“Meanwhile” is undoubtedly Shiga’s most complex work yet. It can be a flat emotionally but its pessimism is sort of interesting.

You should write about video games for the blog sometime, Suat. They seem like an interesting point of comparison for comics….

Suat-

You’ve convinced me- I’ll try to see if I can get somebody to lend me a PS3 and I’ll rent Heavy Rain. The RPGs I listed are definitely on rails, and most of them have only a limited amount of actual branching, but they also carry with them the illusion of freedom because of the other possibilities added on top of the rigid through-line. So you’re probably right, and I was just willing to deal with the rigidity at the time for the sake of the pleasure I had out of the game.

I suppose it’s also pointless for me to hold back reading Meanwhile, seeing as my reasoning was to be able to honestly say at some future date that I hadn’t read it, in the event of making an interactive comic of my own, and yet I’ve now completely defeated the purpose of that by acknowledging its existence in public ^_^;

I still think the ultimate video game would be modeled on the “Giant’s Drink” in Ender’s game- just an environment to explore, with no purpose other than exploration of a fantastical place.

Thank you so much for this awesome article. I feel strangely gratified that we share many of the same favorite CYOAs. “Enchanted Kingdom” introduced me to the brutal side of fairy lore years before I grew into a Sandman-obsessed teen; almost every damn ending to that one involves getting killed by an evil spell or transformed into something awful or enslaved in the Fairy Queen’s silver mines.

A while back, my cowriter Jeff gifted me with a list of all the endings in “Magic of the Unicorn,” with A-F ratings on each one. It’s one of the best presents anyone’s ever given me. For the record, the best ending is of course the one where you turn into a unicorn. I think Jeff decided the worst one is where you jump off the church tower for no good reason and break your legs.

I also loved environment-based Hypercard games and owned both The Manhole and Myst. The theme music from The Manhole still gets stuck in my head every couple of months.

Seconding and thirding the recommendation of “Meanwhile.” Jason Shiga is a dedicated student of CYOA and even works in an awesome “Hyperspace” reference.

I wonder if there can’t be a revival of this genre in comics? If Thomas Disch found “fork-fiction” worthwhile, there has to be something to it…

Aesthetically, it seems an outrage to conventional minds– fiction is still wedded to ideas of fate and determination, perhaps because the “God-Author” trope remains so powerful…even pretty mild deviations like Fowles’ “The French Lieutenant’s Woman” are dismissed as post-modernist goofing around.

You should check out this amazing CYOA site (if you haven’t already.) The creator went through and graphed a bunch of the books, charting the different outcomes and branches. It’s also really great site and information design:

http://samizdat.cc/cyoa/

You can see that the books got more linear as the series progressed. I wonder, in light of your article, if that’s not a result of Packard’s waning influence.

Oh and don’t miss the Flash animations, where you can read one of the books and see your choices mapped out in a kind of graph above the pages. It’s incredibly geeky and awesome.

Oh, and fantastic article, Sean.

Don-

What an awesome site! I am not only completely impressed but also irritated that I didn’t see it before I wrote my article. Although if I had seen it beforehand, I might not have written this, as he covers one of my central points (regarding CYOA’s place in time and later technological developments) in the first two paragraphs! Yikes. Amazing stuff.

As far as the linearity, I think it really boils down to two factors- what Packard told me, and I relayed above, regarding the trade-off between concept/story development and choice and ending complexity, and just that it’s harder to write a book with lots and lots of choices and branching and doubling back! So there’s incentive for the author to take the easier way out.

Shaenon- I find it gratifying as well. ^_^ It’s tempting to see a series of books as a monolith, and in a series that ran for so long and had so many uneven patches, that sometimes means people aren’t willing to dig for the interesting ones. I wonder if I would have rediscovered my interest in CYOA books if the first one I picked up when I came back was “The Abominable Snowman” or “Tennis Star” or something.

And if “Meanwhile” has a Hyperspace reference… I guess I really do need to read it ^_^.

Alex- I find your connection to religious determinism to be very apt. Calvinists don’t read CYOA books.

So, two final things here-

Writing about this has really invigorated my interest to do an interactive, CYOA-style comic at some point in the future, but I wonder at the difficulty of the page-turning aspect in comic form. Even reading a CYOA I would often get spoiled for sections of the book because you can’t really help looking at an awesome illustration you’re passing by, and if it’s an awesome illustration of you getting eaten by a bug monster, then you’re more likely to avoid the bug monster in the future. A comic like that would be filled with such mechanical page-turning hazards. I supposed you could tab the pages like a reference book…. hm.

Number two- I don’t think I really understood until doing the research for this what a huge phenomenon CYOA really was in the 80s. On ebay right now is a little piece of that, a book I’ve never seen before today- “CYOA- Cinderella’s Magical Adventure,” Disney branded. From the description- “The reader becomes involved with Cinderella, but must make choices which will determine if she marries a Prince or not.” Hmmmm. If that really is the plot, then maybe I have to buy it… http://cgi.ebay.com/Walt-Disney-CYOA-Cinderellas-Magic-Adventure-1985-H-C-/190435759692?pt=US_Childrens_Books&hash=item2c56db164c

The artwork is really a mixed bag…some of it is atrociously amateurish…but still compelling.

Sean, your multiple “The End”s had me giggling.

Alex Buchet said: I wonder if there can’t be a revival of this genre in comics?

Actually, there WAS a Ren & Stimpy special that was just like a Choose-Your-Adventure book, with multiple paths, oftentimes looping on themselves, creating new interpretations of the same pages.

Far moreso than Japanese RPGs, I found text-based interactive fiction games to be the most familiar ‘next step’ after my Choose Your Own Adventure phase waned.

IF games were still interactive written stories, they even retain the second person “you” of the CYOA books. The main difference is the much higher degree of interaction afforded the player in the form of a text parser.

People still write great IF games today, and many of the best can be found in the archives for the annual IF competition:

http://www.ifcomp.org/comp09/

You may also be interested in hunting down some of the classics of the form by Infocom, including a couple of games written by Douglas Adams!

Also, I tried my hand at a branching path comic book, which you can check out here if you’re interested:

http://www.gildedgreen.com/sequential/nolimits/index.html

Luke,

I agree with you in the relationship- I just didn’t have enough personal experience with the Infocom games to include it in the article. I’d be interested in trying some of them out now, but it didn’t hook up with my personal experience framework. Apparently the director of the text-game doc “Get Lamp” agrees with you too- it says on his site that he interviewed Edward Packard as part of the documentary.

Your comic looks interesting- I like the simultaneous tracks aspect. There’s a strange spirituality to having all of the possibilities laid out simultaneously- there’s something very difficult to break about the concept of “book as universe.”

Pingback: Page 11, fall in a pit and die: critical assessments of Choose Your Own Adventure novels

Pingback: Ypulse Essentials: ‘Shh.. Don’t Tell Steve’ Comes To TV, Whitewashing ‘Hunger Games,’ ‘I Voted’ Badges Coming Soon? | Ypulse

Fantastic overview of the whole “Choose Your Own Adventure” phenomenon. I remember loving them as a kid. My childhood librarian introduced me to them around 1985 and it rocked my world. Now, as a librarian myself, I pay it forward and recommend CYOA to the kids at my library. These books never fail to please!

Madigan,

Thank you for your kind words, and for being the kind of librarian that looks for what young readers want to read instead of what you want them to read. I see we also share a love of the tools of libraries past- I remember by library cards with fondness- don’t know how long it’s been since I saw that metal stripe. My mother is a retired librarian, and about a decade ago, when they retired the card catalogue, she purchased one of them in an auction. It’s the ultimate useless but attractive storage unit!

Pingback: November Literary Linkdump 1 | Idiotprogrammer

As a child, I read little but Choose Your Own Adventure books, but only recently have I gained any further interest – and the only because of a university course where I had to study my readings as a child.

Since that time (circa 2006) I have tried to collect those older books in the series. In my opinion, it is not so simple as saying the first sixty books are the easiest to find. Many titles between numbers 45 and 70 are actually harder to find than later books in the series, in part because many writers only wrote one or two books.

Apart from Packard and Montgomery (and their children) there were twenty-four other authors during the original series, of whom ten actually wrote more than one book and eight more than two. Richard Brightfield (recommendation The Secret Treasure of Tibet) and Louise Munro Foley (recommendation Danger at Anchor Mine) were particularly significant for their output. Most of these other authors never tried to clone Packard or Montgomery, and they add different flavours to the series.

Julien,

I completely agree. The different authors definitely interjected a wide variety of flavors into the series. As you can probably tell from the above text, I was a big fan of Edward Packard and Ellen Kushner as a child, and I think many of their books hold up pretty well- but I was also partial to a lot of the Brightfield and Munroe Foley books.

It’s been pointed out to me that there were plenty of fans of the original series that really liked R.A. Montgomery’s books as well, and that it’s possible that my clear preference for Packard’s books is as much a function of personal taste as any objective set of standards. I’d be curious to anyone’s reaction to these books coming at them fresh- am I looking at these through the lens of my childhood obsession solely, or do some of the critical observations intertwined here within the personal narrative really hold up for other people?

Anyway, thanks for the comment. I’d love to know what your favorites were, if you have the time at some point.

Love, love your writing. It’s honest and true and fun to read.

Thanks for the kind words, Michael–they are much appreciated.

My friend Ron Wing will be hosting the annual exhibition of his artwork on Oct 22, 2011 in his historic grist mill and gallery located in Benton Pennsylvania. Along with original oils, pastels, watercolors and pencils….There will also be original illustrations of the choose your own adventure books on display. The show will run from 3-9pm one night only. If anyone is interested in information please feel free to email me at pariah_chaos@hotmail.com

Great article.

Thanks much for this wonderfully written (and unexpectedly moving) article, Sean. I’ve also retained my love for this series, especially the first dozen or so.

Earlier today I was saddened to learn that CYOA illustrator Don Hedin (a.k.a. Paul Granger) passed earlier this year (this news led me to your article). When I was younger I preferred the later, “slick” artists (like Ralph Reese) but as my own skills have matured I’ve developed a real love for Hedin’s work. In particular, his collaborations with Packard are my favorites in the series. Wonderful use dead line and hatching; makes me think of my talented pal Jesse Hamm.

Again, thanks. May your adventures end gloriously.

Hey Jon,

I’m really sorry to hear Don Hedin passed. I would have loved to have talked to him about his work. I was most fond of his really grotesque books, especially some of the caricature in Jonah and Chimney Rock–very tasty.

Judith Mitchell in particular seemed to always have a way of making a point as to just how screwed you WERE in some of the endings with her illustrations, as you magnificently showed above. I seem to recall another one of the endings of “Space Vampire” that showed your character just sitting there at the computer alone with this absolutely petrified look on his face as he awaits his doom… I found it so unnerving at the time that I never picked the book up again. No doubt it would make the perfect illustration for the “Oh Crap” entry on TVtropes…

Rather late to comment on your entry, which confirmed many of the thoughts I have about CYOA.

I’m a little older than you and discovered CYOA in 1983, when I was in the sixth grade – presumably the ceiling of the age range of CYOA’s target audience. (But age is just a number, as my middle school carried a respectable collection of CYOAs.) The first CYOA title that I read was Escape (#20). That was the start of my initial love affair with CYOA that lasted some four years. Once adulthood hit, I renewed my interest in CYOA on several occasions, with the most recent being last month. This one is ongoing.

I chose Escape because of its cover art. The cover art of the first 60 or so titles was usually awesome and was a big factor in attracting readers. Much of the credit goes to Don Hedin.

As you suggested, the cover art of the later titles and even the reboots of the older titles wasn’t as cool. I couldn’t agree more. The classic white cover with the red bar on the top showing “Choose Your Own Adventure” in yellow fonts was the best.

Even though Chooseco has revamped some of the classic titles by lengthening them, I still don’t think they’ll have the same impact as the original versions.

And to think: this was one way kids passed the time before there were smartphones.