I plan to do a number of posts blogging my way through n Moto Hagio’s Drunken Dream, released recently by our kind hosts at Fantagraphics. I’m a fan of Hagio’s work…or of as much of it as I’ve seen. (See my review of AA’.) And I have great, great respect for translator and editor Matt Thorn, (who was kind enough to facilitate the inclusion of this piece in an online project I did some years back.)

So basically I was hoping to be wowed by this book. And I don’t think that that’s entirely impossible even still — I skimmed ahead to reread “Hanshin: Half-God,” the one story here that was reprinted in TCJ #269, and that’s still awfully, awfully good (and I’ll discuss it in order in the next post or so.)

However, the first four stories do not live up to expectations. Because they kind of suck. And not just “suck in comparison to what I was hoping for.” They’re out and out crap — presuming you drew little hearts and flowers on your crap and maybe put a little schoolgirl dress on it, and then nailed it to a tree and sang to it odes about the transcendent power of art as it oozed with limpid bonelessness down the trunk to finally crunch ineffably on the leaf-strewn forest-soul.

Anyway. We’ll take them in order. (There are lots of spoilers here, if that concerns you. In fact, I pretty much spoil everything. Fair warning.)

Bianca

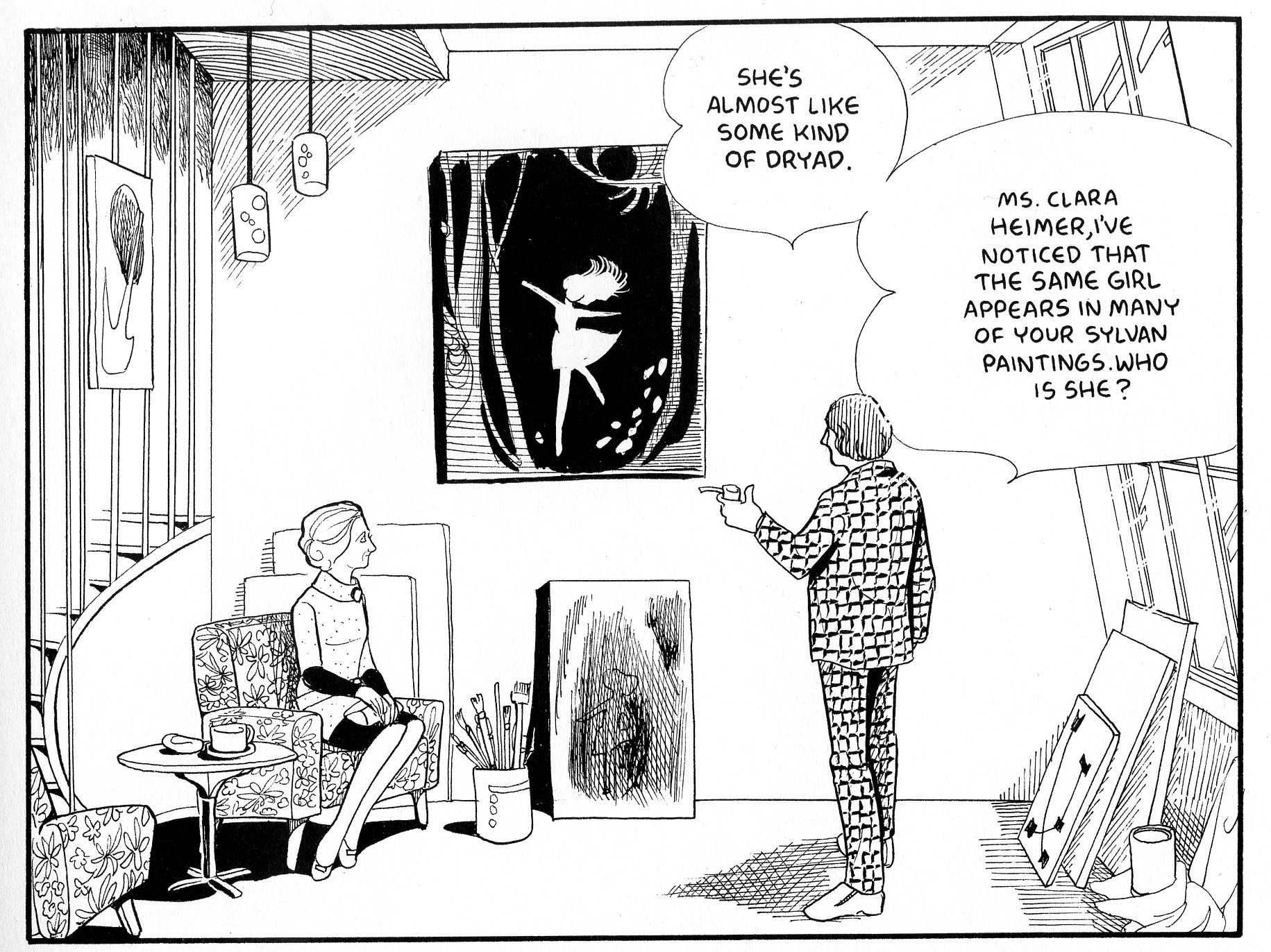

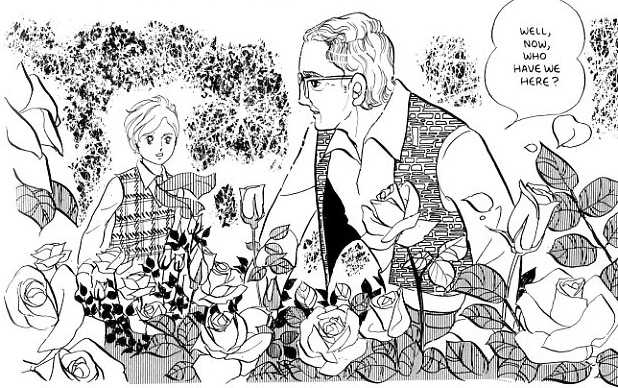

This is framed as a conversation between some guy with an aggressively patterned suit and the great painter Clara Heimer. Aggressive suit guy asks Heimer who that little girl is in all her paintings and she says it’s her lovely inner-child/nature spirit and then she looks up meaningfully as an infinite number of self-help books fall from the sky and crush her and the guy dead, leaving only the empty and aggressive suit to dance wildly, desperately, transcendently upon their moldering corpses.

I wish. Actually she says the girl in the pictures is the titular Bianca, a young ten-year old cousin Heimer met for the first time when she was 12. Said cousin is a free spirit who cannot be contained, which translated means that she likes to run outside and dance in the forest “like some kind of dryad” as aggressive suit guy says. Clara doesn’t understand her free-souled cousin and makes fun of her dreams, causing said cousin to lash out and go dance in the forest some more. But, hark! Free-souled cousin also has a Dark Secret, which is that her parents are breaking up. The final news of their divorce sends free-soul (you guessed it) back out into the forest, where she is so distracted that she falls off a convenient cliff, taking herself mercifully out of the story. But she has, alas, inspired Clara forever. Or as Clara says, “I saw the wind. I saw a dancer. I saw the world of a girl who became one with the forest.” So Clara goes on to spend the rest of her life drawing trite dryad pictures about the wounded child inside all of us and how the trembling spirits need to be free and how you shouldn’t make fun of people’s dreams no matter how clichéd and irritating they are. Let’s…let’s save all the children. Save the babies…save the babies…

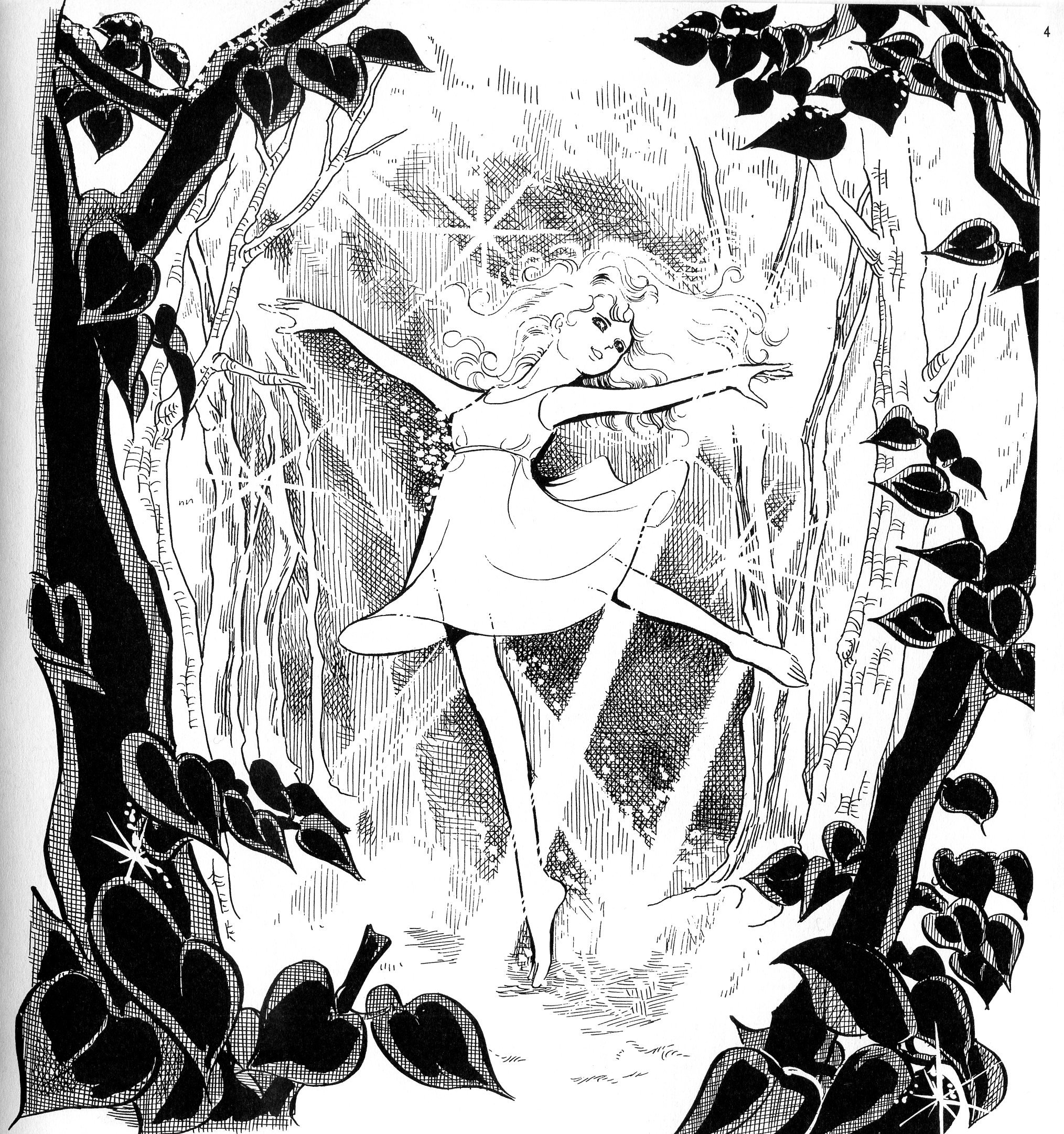

Here, look. Save this, damn it!

The light and trees criss-crossing; Bianca in the center with the airy thin lines of her dress — it’s impressively designed. But it also seems too perfect, with those trees at the side conveniently framing the imge, and Bianca herself stuck dead center. Her pose even makes her look like she’s a decoration on a cake. Hagio’s style is delicate and pretty; layered on this delicate and pretty narrative, it just makes the whole thing so precious it’s hard not to gag.

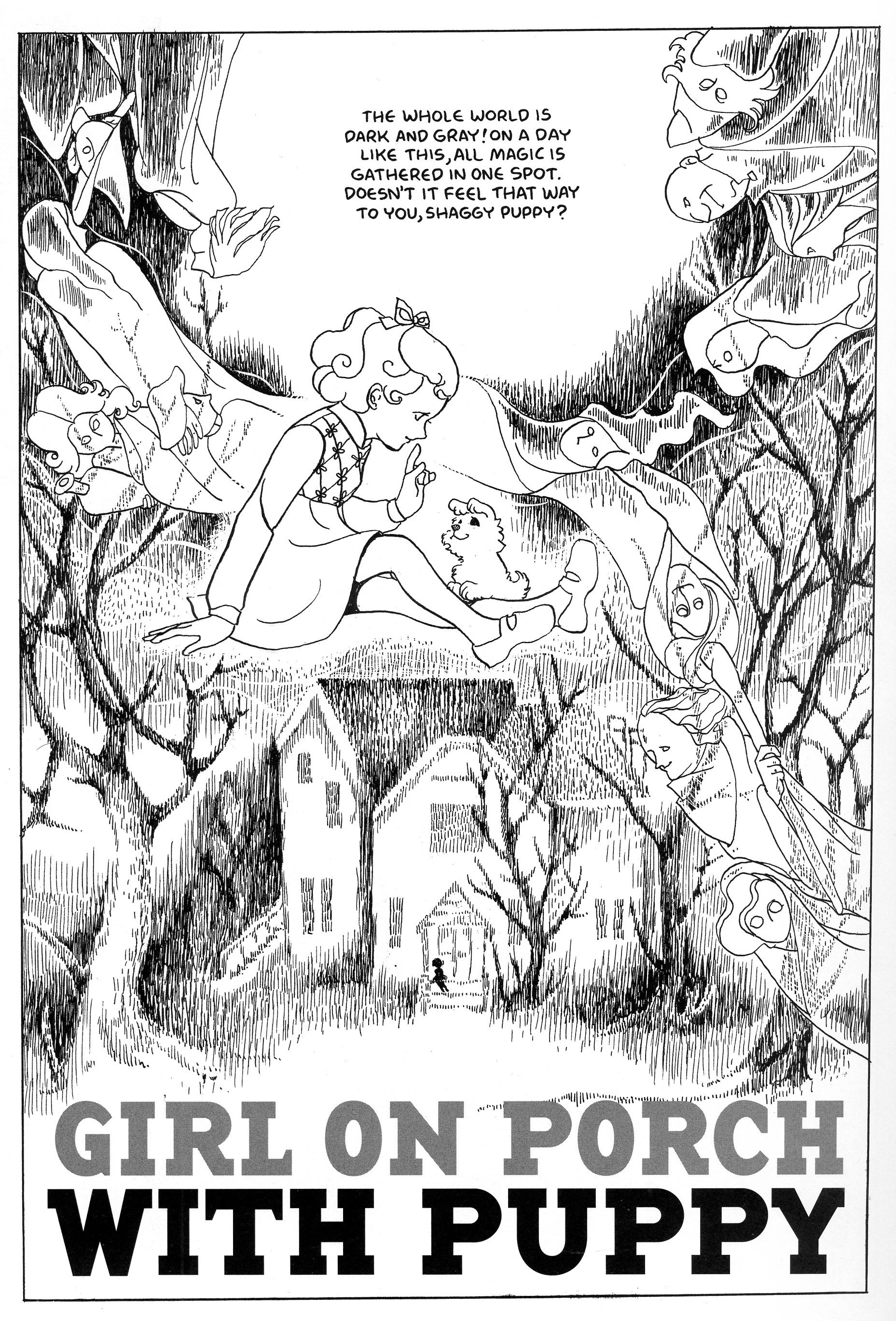

Girl on Porch with Puppy

The opening visual here, on the other hand, uses pretty to contrast with creepy — which only makes the whole thing more disturbing.

I wish those weird, semi-faceless ghosts hung around for the whole story. Unfortunately they don’t. Instead, as far as narratives go, this is basically more “Bianca”, except worse. Like the title says, a sweet little girl sits on the porch and communes with her sweet little lap dog. Various adults (doctor, mother, father, etc.) wander past and wonder what’s up with her and/or express disapproval because she likes to sit outside in the rain. She muses self-consciously about vapidly trite saccharine hallmark card drivel and about how much more wonderful she is than boring old adults (“I don’t know what the doctor’s thinking either. But I don’t think it’s about the sky or windows or flower buds or the fairies behind the leaves”).

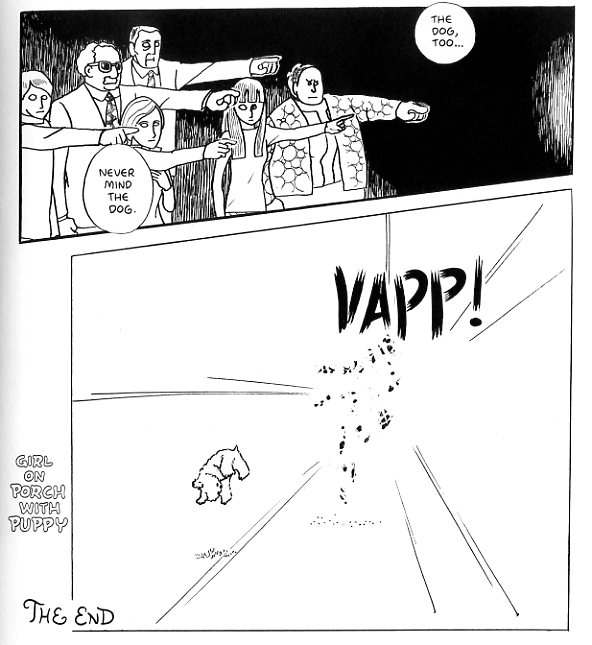

So the boring old adults get together and decide “we can’t have one person thinking differently from everyone else like that.” Then they point at her and she explodes. Admittedly, it would have been better if they did that on the first page rather than the twelfth. But beggars can’t be choosers: it’s an unexpected but welcome happy ending as far as I’m concerned.

Autumn Journey

A young boy named Johann sets off to meet his favorite author, Meister Klein. He ends up hanging out with Klein’s daughter, and there’s some romantic tension, until…she discovers Johann is Klein’s son, from a family Klein abandoned. Johann isn’t mad at Klein, though, because he read one of Klein’s books and realized that “He had lived so much longer than I, known so much sorrow, and yet he told his stoires with such warmth, such sincerity.” You can tell he’s sincere because…flowers!

In short, if you’re a great artist, you can’t be a complete asshole and moral failure — an insight flagrantly contradicted by everyone from Pablo Picasso to Ezra Pound to Kanye, but what the hell. Johann’s enormous eyes leave little room in the skull for grey matter, so I guess he can’t really be held responsible for lapses in logic. Anyway, at the end his father runs after him as he rides away on a train. That’s redemption, kiddies.

Perhaps it’s not fair, but I’ll admit this is kind of a pet peeve of mine. Maybe it’s because I have a number of friends whose fathers walked out on them; maybe it’s because I’m a dad myself. In any case, leaving your kid flat in order to go start a new life strikes me as one of the most contemptibly loathsome things a person can do, definitively worse than any number of minor felonies. The idea that all is well if you write good novels and shed a few tears a bunch of years down the road — that’s just not okay. I mean, is this guy going to start coming through with child support or what? I know, I know — Hagio doesn’t actually care about such mundane issues, or, for that matter, about the characters or the moral issues as long as she can have her final tear-stained moment of sentiment and reconciliation. And you know what? That’s not okay, either.

Marie, Ten Years Later

This is a classic love triangle; nerdy guy loves girl; hot guy loves girl; hot guy gets girl; girl dies mysteriously and conveniently; hot guy and nerdy guy get together and dance around the fact that they actually love each other and never really cared all that much about the dead girl; cue reminiscences about how happy they all were when they were young; fade out.

If this were by a guy, I’d definitely be pissed off by the way that the girl in question is reduced to a cipher for male (heterosexual and homosexual). But you know, since it’s by a woman — I’m still kind of pissed off actually. I guess maybe what saves it is the fact that the two guys are also utterly uninteresting, so even though we learn nothing about the girl except that the guys desire her, it doesn’t really feel like Hagio shortchanged her all that much. The insistent nostalgia by vapid characters for a vapid ill-defined past is irritating, but so empty it’s hard to get worked up about it. The first three stories really made me angry; this was just boring. So maybe that means this was my favorite of the four?

__________________

I’d like to think these were all juvenelia, but that doesn’t seem to be the case. The first three were from 1977 and the last from 1985 — Hagio wrote them in her late 20s and early 30s, by which time she was already an established and lauded mangaka. I’m forced, therefore, to conclude that Hagio is capable of producing dreck, at least some of the time. [Update: JR Brown in comments points out that the stories were actually printed earlier, before Hagio was established.]

Still, the kind and heft of the dreck are interesting. Sometimes you can get more insight into an artist from her failures than from her successes. Reading these stories it became clearer to me than it had before how much of Hagio’s work (or at least what I’ve read) seems to be about not just repression, but displacement. She’s obviously obsessed with themes of child brutalization and abandonment, the pressures of social conformity, and illicit love. But she explores these ideas through deliberate misdirection and metaphor, cutting the core of the stories loose from the material that inspired them so that the emotions suffuse the material, breaking through at unexpected moments or in odd ways.

For instance, in that first story, “Bianca,” the tragic dryad cousin who dies when her parents are breaking up — it seems likely that the break up problem stands in other problems, specifically physical abuse (which is much more likely than divorce to lead to a child’s death.) And, as I suggested above, Bianca is clearly meant to be the artist’s own traumatized childhood; a childhood linked, through the artist’s powerful feelings for Bianca, to repressed same-sex emotions. And love the can’t quite speak its name surfaces as a trope in virtually all the stories; the girl in the second is reprimanded for kissing her dog; in the third Johann is linked, teasingly but still, to a girl who is his foster sister; in the last, as I said, there are intimations of homoeroticism between men.

The point, for Hagio, then, are the buried meanings and how they resonate. This worked well in AA’, where the vague sci-fi setting turned everything into a metaphor; the world didn’t need to hold together since the world wasn’t real in any case. In contrast, the stories here are all too specfic; she doesn’t seem to have room to move around in them. “Bianca” and “Girl on Porch With Puppy” make their metaphors too straightforward, trilling “Flower Power!” over and over in piercingly crystalline tones. “Autumn Journey” and “Marie”, on the other hand, exist too firmly in the real world — they demand some sort of actual psychological insight on the level of character, while all Hagio wants to do is get to the darned emotional catharsis. Hagio is an artist who thrives on spaces and emptiness — she goes astray when, as in these stories, she tries to say what she means.

Whew! Pretty bad…what was Fanta thinking?

Well, I’m an outlier, and a cranky one at that; everybody else seems to like the first few stories fine. And as I said, I think some of the later stories in the volume look very good — Hanshin is awesome.

And (as I also said) I don’t think it’s necessarily a bad thing to have more of a major artist’s work in print, even if not all of it is fantastic. You can learn something from stories that aren’t so hot. I mean, nobody says, “why publish these old crappy Ditko stories?” You publish them because it’s Ditko, and he mattered even when he was producing things that weren’t very good.

Anyway, maybe I can convince you to buy the thing over the next couple of posts….

Pending the arrival of Hagio’s apologists, I’ll say that this review reveals why you probably won’t like a lot of classic shojo. I mean, the antagonism towards flowers in “Autumn Journey”! : P

I would say that 3 out of 4 of the stories are absolutely typical of the genre: the sentimentality, the on your sleeve emotions, the painful but simple faith in human beings. To paraphrase an argument you deployed in the Ariel Schrag roundtable, this suggests a disdain for literature directed at the more formative minds of young girls (its limitations and its requirements). I have no idea whether the stories have any relation to Hagio’s childhood but it’s very clear to me that the stories are directed towards the probable experiences of young girls in Japan who might be reading them: that parental repression, that curtailment of their spirits (adventurous, artistic, ambitious) or their feelings of resentment towards their parents (of which their is some wish fulfillment in the third story). So just as the solo Kurtzman EC war stories are seen nowadays as a kind of superior children’s literature (more morally complex yet not excessively dense), so too can some of these tales be appreciated in that light.

Flowers are fine! I got nothing against flowers. But dumping them on a pile of offal doesn’t make the offal any prettier, and I resent the effort to make me think it does.

I like lots of things aimed at young girls, from Twilight to the Marston/Peter Wonder Woman to quite a bit of shojo (though I’m more familiar with modern iterations of the genre.) I don’t dislike this because it’s for young girls. I dislike it because it’s cliched, clumsy, and dumb. There’s plenty of art for young girls that is thoughtful, beautiful, funny, moving, smart, or all of that. Some of that art for young girls is by Moto Hagio. This just doesn’t happen to be it.

The wish fulfillment aspect of Autumn Journey hadn’t occurred to me, but it makes sense — and I think it’s still a bad idea. Girls are so often told that they should forgive when they’ve been wronged; I don’t find a further iteration of that message aesthetically or morally persuasive.

Was this from Dirk Deppey’s new Fantagraphics line?

Noah:

“There’s plenty of art for young girls that is thoughtful, beautiful, funny, moving, smart, or all of that.”

Amen!

I have a moonlight job as a reader for the children’s/YA line of a large French publisher, La Martinière, evaluating English-language books for eventual French editions. I’m very much aware of differences in quality between one book and the next. And, I’m sure, so are young girls…I have no daughters, but I do have 4 nieces.

The skills needed for a children’s or young adult book are exactly the same ones as needed for a “grown-up” book. In fact, the former is probably the harder field: unlike we adults, kids don’t turn off their bullshit detector.

As Dirk would be the first (and probably the second and third) to point out, it’s not his line, though he helped facilitate it. Matt Thorn is the editor and translator.

I don’t know that kids’ bullshit detector is any better than adults’, really. Certainly kids like some really bad things. My son will read pretty much anything with a super hero tie-in, including those horrible DK picture books, which are far worse than the Hagio stories.

I’d point out that the dates in the indicia appear to be for the collected editions from which the stories were drawn, not the date of original publication; Bianca dates to 1970; Girl on Porch with Puppy and Autumn Journey to 1971; Marié, Ten Years Later to 1977. Hagio started her career in 1969, and became well-known some time after Poe no Ichizoku started in 1972, so the first three at least cannot be considered the work of an “established and lauded mangaka”.

A Drunken Dream and Other Stories is something of a historical retrospective, as well as an introduction to the artist. The first three stories date to just before shoujo started to open up its permissible topics and subject matter; when Hagio debuted, shoujo manga was still expected to consist of wholesome and improving stores for a strictly pre-teen audience. These stories were unusually dark for the era, even if they seem facile now. I’d encourage you to read the included interview, or better yet the full version on the TCJ website.

Maybe he’s right and you’re wrong?

Noah,get used to it– you’ve got another 20 years of debating that point ahead of you.

Kids will like trash, sure, but they tend to dislike PHONEY trash.

(The above was in reply to noah’s last post here.)

Hey JR. That’s something of a relief, actually — as well as making a lot more sense.

I did read the interview! It was when it originally came out though; I’ll probably reread it when I’m done with the book…

As my wife always says–it’s somewhat more difficult to write a good kids book, because it needs all the things a good adult book has, but usually has to accomplish it with a more limited vocabulary. There also has to be care not to talk “over” the kid–but perhaps more importantly, not to talk “down” to the kids.

That said, kids will consume all kinds of horrid dreck (if my own two daughters are any indication). My eldest discriminates between those things she likes and those things she doesn’t, but for a long period, she pretty much liked anything she read—and some of it was pretty godawful.

So you’re going to blog your way through the entire thing? What if they rest of the stories are this bad?

Did you forget what you went through with “Man-Thing?”

Well, I know one of them is great…and I glanced at the others, which also look better.

Also, this isn’t as long as Man-Thing.

Pffff! Noah totally wimped out on Man-Thing.

Shame on you, Richard, for evoking the Berlatster’s humiliation.

I didn’t wimp out! I read the whole darn thing!

I wasn’t happy about it, though…

Poppycock! That’s because you lack empathy, Noah.

You should’ve stood motionless in a mudpit for 12 hours before daring to criticise Man-Thing.

Personally, I’ll admit that my ‘Giant-Size Man-Thing’ is my most precious possession.

“Personally, I’ll admit that my ‘Giant-Size Man-Thing’ is my most precious possession.”

LOL!

I’m getting the impression the girliness of this book is making you boys a little nervous.

I haven’t read this yet and I take your word for it, Noah, that the target readership is YA age. But the resonance that I get from the stories you describe and the art you sample is of being a much younger girl child — especially Bianca. Maybe the difference between this and the YA things for girls that you like — Twilight, Wonder Woman — is that those YA books are about girls-becoming-women whereas this seems more about girls remembering girl-childhood. These images and stories (as described) strike a nostalgic chord with me. I loved this kind of thing at 8 or 9.

I’ll let you know if that holds up once I actually read the book.

Yeah, the Man-Thing discussion is maybe an overly revealing detour on this particular thread.

I think it’s Suat who suggested the YA audience. JR may have a better idea of the exact target audience of these stories? WW is for pretty young girls, though, and I think it’s more about girls playing at being woman/girls (like dolls) than actual coming of age (which is obviously Twilight’s thing.) I mean, I doubt the Hagio is for kids under 8, which is probably where WW’s readership started.

I’m curious to see what you think of the book as a whole. I can see someone liking the atmosphere or the art for the first few, I guess, but the narrative’s are so thoroughly stupid I just can’t hack it.

I’ve read the next story in the book now, though (“A Drunken Dream”) and it’s way, way better, thank goodness.

Nope, quite the opposite. You just have to look at the girls being depicted to know who the manga is being targeted at. And, in general, for these 4 stories it’s probably not YA though they may have read them as well. Think Heidi or Anne of Green Gables as it is viewed today. That is, I can imagine lots of girls under the age of 13 reading these kinds of manga and watching any related anime.

I’m not sure where the first few stories were originally published, but they were almost certainly aimed at girls in the 6-12 range, the standard market for pre-70s shoujo.

I think several of the later stories (Hanshin, Iguana Girl, The Willow Tree) ran in Petit Flower, which had more of a tweens-to-twenties demographic.

That makes sense. Thanks Suat and JR.

Pingback: Rummaging in the manga attic | Anime Blog Online

Wow! I just found this today. Sorry to come so late to the party. I’ll respond to your reviews the same way you did to the stories, i.e., as I read them.

I don’t want to argue the merits of the works, because if you don’t like something, you don’t like it, and no amount of exegesis can change that.

But just some factual clarifications. 1977 is the *copyright* date of the first stories, not the year they were published. “Bianca” was published in 1970, when Hagio was 21, but was actually written/drawn a year or two earlier. “Girl on Porch with Puppy” was published in 1971, when Hagio was 22, but this one, too, was actually created a year or two earlier. “Autumn Journey” was also published in 1971.

And now for some cultural/historical background. This was a time, both in Japan and throughout most of the developed world, when youth culture was pretty melodramatic and more than a little self-indulgent. Things that seem clichéd and embarrassing today were seen as “real, man,” and the kids could “grok” it, you dig? Just think about “Easy Rider.” It is worshipped by Baby Boomers as anthem of their generation, but most young people watching it today would probably think, “What the hell are these people doing and why the hell should I care? And what’s with the random redneck drive-by shooting ending?” The Baby Boomer response is, “You had to be there.” Ditto for these stories. Perhaps I should have written a brief introduction to each story in order to provide this sort of context, but it never occurred to me, probably because I’m too close to the work.

As a social scientist (of sorts), this context is interesting to me, and it is a matter of historical fact that these stories were considered to be groundbreaking and fresh in the world of shoujo manga, and were extremely influential. If you’re going to measure them against something, it would be more fair to measure them against 1) other shoujo manga of the day, or 2) English-language romance comics of the same period, keeping in mind that the target audience here was considered to be girls aged 8 to about 15.

On a personal level, I chose these stories not only because Hagio aficionados consider them representative or her work at the time (they are), but because, 1) “Bianca” is just damned pretty to look at, and showcases her technical skills as a young illustrator (if not storyteller), 2) “Girl on Porch with Puppy” captures the kind of quirky, Twilight Zone, sci-fi/fantasy element that was influenced by such male artists as Shinji Nagashima, but which was practically taboo in shoujo manga of the day, and 3) “Autumn Journey” embodies the vaguely-European adolescent boy romance that was influenced by European cinema of the day, and which Hagio went on to develop in more sophisticated ways, in works like “The Heart of Thomas.”

In short, I wanted to represent her whole career, not just collect a bunch of first-rate stories that modern anglophone readers today can easily appreciate. If I had wanted to do that, I would have selected very different stories, and there would probably be none from the first few years of her professional career.

But, hey, at least nobody dies in “Autumn Journey.”

Greetings Matt!

Just wanted to say that I loved the Hagio book so much that I’ve only read half of it so far- felt the need to savor it rather than plowing through it the first day I got it, which I certainly could have.

That being said, as it might be clear from the comments, some type of commentary, or specifically context, would definitely have aided myself, and judging from this review, Noah too, in starting into the stories. I had the same confusion as he did with the publication dates of the stories. Maybe a single page with original publication dates and name and description of the magazine they originally appeared in would have been most useful? Especially in a book covering such a wide span of time, it seems like it would be important to provide some context.

And count me as someone who thoroughly enjoyed the early stories. Looking forward to more (Heart of Thomas, perhaps?)