Bruno Lecigne’s “De la confusion des languages” (on the mixing up of the languages)

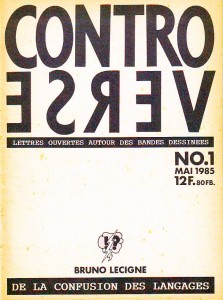

My monthly stumblings are, sometimes, restumblings, really… This past weeks I restumbled at least twice: on Otto Dix’s Der Krieg (the war) and Bruno Lecigne’s “De la confusion des languages” (Controverse – controversy -, May 1985). In “De la confusion…” Bruno Lecigne presented eight chapters about comics criticism. I will summarize them trying to avoid misrepresentation:

(I) After being a subculture designed to amuse children comics reached adult readers and achieved official recognition in France. This meant that, after being devalued in their totality, comics started to be valued also in toto. It’s the amalgam: “there’s a distortion between the genre’s reality, which is multiple, and its image, which is assembled.” This means that a comics auteur is just a comics professional. It doesn’t matter if s/he does stereotyped products for children (normalized distractions for everyday consumption) or ambitious, personal work: “there’s confusion between the “auteur” as a professional (social status) and/or as a creator (artistic status)[.]” This means that institutional prizes and grants are given both to innovative, personal, work and commercial successes without any creativity. It also means that critics value everything, without any criteria.

(II) Comics in France started by being an infraculture rejected by the official instances. Academia either ignored or denigrated them. In the latter case academics based their attacks on three major points: comics are morally corrupt; comics are culturally harmful because they deturn from the real culture (particularly from literature); comics are aesthetic junk. Facing this rejection and suffering from a lack of legitimization the comics fans are going to organize a milieu in which a parallel legitimization is going to appear (through magazines, fanzines, conventions, collectors, specialized critics; everything in closed-circuit): a paraculture was born (the word “subculture” could also be used, I suppose). This subculture is not completely watertight though: some intellectuals will function as ambassadors to the mainstream media and academia. They will defend comics as: 1) just another art form; 2) unpretentious and fun; 3) ultraculture (the underground).

(III) There’s no objective reality of artistic creation. Concepts like “auteur” or “producer” are historically determined. They’re part of a mentality, of an ideology. Denouncing the mixing up of the criteria means denouncing a cultural manipulation: “a morality of consumption can’t be, without deception, credited to an ideal of creation.” The social status of the artist varied through history: “archaic phase: the wizard; classical phase: the craftsperson; Romantic phase: the artist; modern phase: the creator.” These categories are sociological, not artistic. These historically determined concepts may be seen as “values” and used retrospectively (e. g.: the work of Alfred Hitchcock or Howard Hawks seen as auteur creations). “All speech about art presupposes an implied or confessed ideology which supports economical strategies within the field, new to comics, of the institutionalized culture. The brand of creation is bandied about indiscriminately by certain editorial policies [.] […] The propaganda of cultural activities, for instance, dissimulates a real practice of commercial criteria – these contradictions […] are stifled by the amalgam though.”

(IV) The reviews are the privileged place of the mixing up of the languages: two examples: an anti-intellectual review in (A Suivre) (comics are fun and intelligent means boring) and a review in L’Année de la bande dessinée 84 – 85 in which the writer (Thierry Groensteen) praises François Bourgeon as a craftsman to claim his status as an auteur afterwards. He bases his claim in nothing: “Bourgeon is an auteur because he is an auteur.”

(V) In this day and age we view creation as a detachment from commercial constraints. In the comics milieu it’s rarely the case: even Tardi (with Adéle Blanc-Sec) and Chantal Montellier (with Andy Gang) must submit themselves sometimes to the restrictions of the series. Auteurs should also be free from editorial policies, but, again, that doesn’t happen a lot. The point isn’t that commercial and editorial constraints lead to an inevitable lack of quality. “What’s questionable is a speech based on the freedom of creation which cannot be valid because it hides “industrial” constraints and imposed rules – self-imposed or not.” An autor like Tardi (or Guido Buzzelli, sez I), is in a schizoid position: his personal work coexists with his alimentary production. “[A] dynamism art/commerce is, as everywhere else, sustainable, but its ambivalence, if doctored by a speech, is a falsification.”

(VI) New approaches to art creation include the viewer as “producer of meaning” and stress art’s polysemy. As Revault d’Allones put it: “The abuse that constitutes calling works of art productions may allow an ideological manipulation in reverse: mistaking industrial products for works of art, veiling, in this way, the nakedness of the profit under the patched vest of beauty.” […] “The problem is not to determine which doctrine of creation is the “true one,” or the more adequate to comics (where all strata coincide: production / mass consumption, innovative or avant-garde explorations, fetichization, etc.), but to dispute the mixing up of the languages, namely the absurd support that a global positive cultural image gives to production conditions that are just commercial. The “vest of beauty” may not fit on everybody, that’s normal; but the universal acceptance of clichés may dress everybody and that is a pity, or it is indeed sinister.”

(VII) If real comics criticism doesn’t exist what passes for comics criticism in the media does have a strong presence. It privileges the adventure series for children: “escapist comics guided by the stereotypes of the heroic fantasy where the image is in the service of the anecdote, without an aesthetical surplus. Being an easily digestible product it implies a consumer’s reading: at the first degree of the narrative’s transparent content, evaluating the images by their effectiveness and their “prettiness.” These rules of the readers are also, quite often, those of the critics who are going not to distance themselves, but to reiterate these principles fixing them in a speech.” The escapist series becomes the epitome of comics greatness. “Integrating has their sensitive model the laws of the series, critics are in accordance with commercial recipes, to which they give the legitimation of the “artistic” speech and the “cultural” value judgment: here’s the language of the mixing up.” Comics critics are also archivists and hagiographers.

(VIII) After a feminist manifesto by four French comics artists (Nicole Claveloux, Florence Cestac, Chantal Montellier, Jeanne Puchol) published in the mainstream newspaper Le Monde (1985) anti intellectual attacks followed (feminists lack humor and comics are fun, as we already know!): “[the manifesto] rubbed the wrong way a certain mantra of self-satisfaction; instead of linking filled box-offices with creative qualities, variety of style, contemporary inspiration, the Monde‘s page links it to clichés, uniformity, poor imagination or complete absence of imagination in favor of a cocktail of formulas.”

To fully understand the above we need to go back 25 years and understand its social and historical context. It’s a controversial text, almost like a manifesto, because Bruno Lecigne felt during the eighties that the revolution which started a decade earlier was being stifled by the temple sellers. In his interview with Jean-Christophe Menu (L’éprouvette # 3, January 2007) he calls the eighties “les années fric” (the dough years). On the other hand I will not underline enough the fact that this is my selection, my reading of Bruno Lecigne’s text, not the text itself, obviously.

Is the divide between art and commerce that wide? Bruno Lecigne himself says that it isn’t. He wanted to attack comics’ pseudo-critics and their blindness, not any artists (he even says that commercial and editorial constraints may lead to quality books). The problem is that citing Hitchcock and Hawks, as he does, without questioning (or not) the Cahiers du Cinéma‘s legitimacy to call auteurs to these directors (or, at least, to write briefly about the subject) undermines a bit, in my opinion, Lecigne’s points. These are painfully difficult questions and things seem (even if they aren’t) too clear cut in “De la confusion…”

That said I’m fully with Bruno Lecigne, as all of you who are still reading know perfectly well. I think that the movie industry didn’t impose as many stereotypes and formulas to Hawks and Hitch as the comics industry does to their hired hands (as Lecigne also says: enforced from outside or self-imposed doesn’t really matter).

Did things improve during the last twenty five years? I don’t think so. Amalgamation is still being practiced and a lot more pseudo auteurs are being lauded than the real ones (as the year 2000 lists painfully proved to me; I don’t know if comics critics are viewing things differently ten years later, but I doubt it). The best though is to listen to Bruno Lecigne himself because Jean-Christophe Menu asked him just that in 2007: “There was, back then, a clear cut frontier between what was “culture” and what was not. That line doesn’t exist anymore. […] Everything that was minor or subculture […] lives perfectly well, in a general way, in a global production and consumer system of “cultural goods” and “cultural contents.” […] There’s an openness which is the one we fought for, but the other side of the coin, that we didn’t predict, is that everything is equal to everything. […] There’s a generalized softness, everything floats with its bellies up, without determination, without any definition. The great antagonisms ceased to exist. Since comics won the economical combat in France (it’s a profitable part of the book industry), it won its cultural combat as well at a moment in which it doesn’t matter anymore.”

Can you find a more pathetic irony?

Hey Domingos. Thanks for this; I hadn’t heard of Lecigne, and it seems like a very interesting article.

As you probably know by now, I”m pretty resistant to the main idea here, which seems to be (as near as I can parse) that art and commerce are opposed, and/or that art can’t be art if it’s commercially constrained. There are a couple of reasons why I disagree.

1. I just don’t think it’s true. There are many, many great artists (Shakespeare, Dickens, Mark Twain) who also enjoyed and pursued commercial success in a fairly thoroughgoing way. Some of these (Stevenson, for example) even wrote for children. Given that, it seems like you either have to throw out a huge chunk of the most canonical artists (which you may well be willing to do!) or shilly-shally around the categories of commercial constraint and personal vision in a way that renders those terms meaningless.

2. I think that, under the guise of a kind of Marxist analysis, this sort of binary really throws out the most important part of Marx. That being — there isn’t a way to get outside commercial considerations. The personal is always constrained by the means of production. You can certainly look at the differences between, say, how Virginia Woolf produced her novels vs. the way that Herge produced Tintin, and that’s a valid method of criticism. But the difference isn’t that Woolf is pure and Herge stained by commerce; rather it’s that Woolf was coming from a social class and a social situation which allowed certain forms of production (most notably, she was independently well off enough to set up her own press) while Herge was in a situation which allowed (or demanded) others. (Raymond Williams has a really good article about how the Bloomsbury Group’s class and social status produced an ideology of non-ideology.)

I actually like Virginia Woolf a lot more than Herge, and not least for the reasons (I presume) you do — she’s much more thoughtful about everything from politics to gender relations, much more ambitious formally, etc. etc. And you can certainly relate those differences to realities of production. But you can’t say, this person is tied to the market and that person isn’t; it has to be, this person is tied to the market in certain ways, and that person in certain other ways. Which to me at least means sweeping evaluations (constrained by the market = bad) don’t really hold up. You have to make individual determinations, in which discussions of means of production are certainly relevant, but not necessarily determinative in a one to one way.

I do agree that the fannish culture of comics criticism is resistant to certain theoretical approaches, be they Marxist or feminist, and that that is (at least in my view) unfortunate.

I was just looking at this article in L’Eprouvette 3, haven’t had a chance to read it yet. I’m not so sure I’m that eager to read it now, though, as it doesn’t appear to relate to issues I’m particularly concerned about.

Noah: “As you probably know by now, I”m pretty resistant to the main idea here, which seems to be (as near as I can parse) that art and commerce are opposed, and/or that art can’t be art if it’s commercially constrained.”

That’s what it *seems*, but that’s not it at all.

The problem is not quality vs. trash or art vs. commerce. Lecigne is against what he calls the “amalgamation” (at a certain point “all comics are trash” became “all comics are great”) but even worst than that: he wants to denounce the real reasons behind it. Which are economical, of course.

I cut most of his didactic explanations from my description because I find them too simplistic. That doesn’t matter much because he just wanted to underline that the ideas behind what we consider an auteur are historically determined. We live in the age of the creator, as he put it. That’s what lead comics publishers and editors to deceive the powers that be into believing that their hacks were really avant-garde creators. They don’t need to do that anymore because today everything is equally good. Twenty five years ago they wanted to socially legitimize their artists and that was the only way.

I think that the amalgamation is more alive than ever. That’s why, if parts of this text are out of date, the bulk of it still matters.

I think the insight that the auteure theory (in whatever permutation) is a historical process rather than an absolute truth, and that it’s about legitimization, is entirely valid. And it’s certainly worth remembering that Herge (for example) worked with assistants.

But surely the emotional/moral oomph of the argument rests on the idea that commerce is bad, that it’s a factor in some art and not others, and that only art for which it is not a factor can really be considered “art”. Otherwise, there’s no need to call the situation “pathetic”, right? If it’s just an issue of bad nomenclature, that’s perhaps irritating, but hardly anything to get especially exercised about.

Or to put it another way — I’m perfectly willing to agree that the move to focus on/respect pop culture as aesthetic is based in material interests. However, I think it’s important to also point out that the claim that aesthetics should be reserved for personal visions unsullied by material interests is *also* based in material interests. That’s not to say that they’re equivalent in some moral or political sense — obviously it depends what the material interests are, how they’re being used, and so forth. But to address those issues you have to look at particular cases. Praising all pop comics creators as auteurs is no more justifiable than damning them all as hacks.

I’ve been looking for an excuse to quote Terry Eagleton’s “After Theory,” and this seems as good a one as any.

“Another historic gain of cultural theory has been to establish that popular culture is worth studying. With some honorable exceptions, traditional scholarship has for centuries ignored the everyday life of the common people…Today it is generally recognized that everyday life is quite as intricate, unfathomable, obscure and occasionally tedious as Wagner, and thus eminently worth investigating. In the old days, the test of what was worth studying was quite often how futile, monotonous and esoteric it was. In som ecircles today, it is whether it is something you and your friends do in the evenings. Students once wrote uncritical, reverential essays on Flaubert, but all that has been transformed. Nowadays, they write uncritical, reverential essays on Friends.”

Thanks for putting this down, Domingos.

Noah: “That’s not to say that they’re equivalent in some moral or political sense — obviously it depends what the material interests are, how they’re being used, and so forth.”

And how would apply these ideas to the current desire to “rediscover” the comics craftsmen of the past, those cartoonists once seen as hacks during the “revolution” in American comics critical thinking during the 80s and 90s? I think Domingos’/Lecigne’s point that “at a certain point “all comics are trash” became “all comics are great”” is a provocative summary but it’s not the complete answer. Nor is the reduction to commercial requirements and demands completely satisfactory. The situation is obviously more complex than this simple statement. There’s also the possibility (?fact) that this “revolution” was never really embraced by the comics reading public; that it was not a revolution in aesthetic standards (championed in the U.S. by The Comics Journal) but a movement which simply resulted in a broadening in taste. Thus the all accepting fan culture (which was frequently attacked in that magazine) far from being weakened was strengthened by this movement since they brought the values associated with fandom to the very institution which once attacked them.

In the same way, how does what Eagleton is saying apply to the current situation in comics? Domingos and Lecigne seem to be more concerned with the aesthetic worth of certain comics while that Eagleton quote seems to be about what is worth studying which has less to do with the same.

the more things change, they more they stay the same …

Well, “aesthetic worth” and “worth studying” have more than a little to do with each other. The defense of high art was often that it discussed or dealt with universal human values in a way pop culture didn’t; once you decide that pop culture can address those values as well, there’s little reason to ipso facto think the first is superior to the second. The move to a belief that meaning is located with the reader as well as the writer (which Eagleton talks about elsewhere in the book) also undermines the kind of aesthetic hierarchy which Domingos and Lecigne seem to be arguing for.

I think your account of what happened to fan culture is pretty interesting. It also suggests that the change in comics is connected to the change Eagleton discusses, (though somewhat unconsciously, and perhaps not in quite the same way.) That is, the idea that you can write about Friends and be an academic seems analagous to the idea that you can write about Chris Ware and be a fan. As Domingos says, the high art/low art barriers have been pretty thoroughly decimated at this point, so anything goes.

Suat wrote “There’s also the possibility (?fact) that this “revolution” was never really embraced by the comics reading public; that it was not a revolution in aesthetic standards (championed in the U.S. by The Comics Journal) but a movement which simply resulted in a broadening in taste. Thus the all accepting fan culture (which was frequently attacked in that magazine) far from being weakened was strengthened by this movement since they brought the values associated with fandom to the very institution which once attacked them.”

That’s the truth fer sure!

Do you think that’s a good thing, a bad thing, or a neutral thing Frank? I think Suat and Domingos think it’s bad; my sense from reading some of Matt Seneca’s pieces is that he thinks it’s good. I guess I lean more towards it being kind of unfortunate, though not always or absolutely so….

Noah:

What’s pathetic is the fact that so many comics critics fought for legitimacy and now that they achieved their goal it doesn’t matter anymore. This is pathetic on a Charlie Brown level, methinks.

Plus, you say: ““aesthetic worth” and “worth studying” have more than a little to do with each other.”

I don’t think so. Everything is worth studying in academy these days (I’m just stating a fact, not criticizing or anything…), but this doesn’t lead to the reverse conclusion: everything worth studying has aesthetic worth. Academics may study comics for lots of reasons. They don’t need to be interested in art or literature in order to do so.

Sorry for my insistence, but I warned against reading this 25 year old text with today’s eyes: the anti-commerce stance is typical of modernism. It’s absurd today. Lecigne clearly states that it is a sociological problem, not an artistic one. Bathélémy Schwartz and Balthazar Kaplan (of _Dorénavant_’s and _Controverse_’s fame) were even more radical when they defended that true artists shouldn’t worry about money.

Suat:

I’m not sure if _The Comics Journal_ was anti-fandom. But I’m sure of two things:

1) it was guilty of amalgamation (which is against the championing of high aesthetic standards); 2) it never had a coherent editorial policy.

The magazine could only have been seen as elitist and intellectual by hardcore superhero fans. For economical reasons it could never have been what they thought that it was (many without even reading it). With me as managing editor the ship would have sunk in a jiffy.

Noah, again:

I surely agree with this: “Praising all pop comics creators as auteurs is no more justifiable than damning them all as hacks.”

I mentioned a weakness in Lecigne’s text already (he doesn’t address your above point at all), but there’s another one: he doesn’t mention any names. (I wrote Thierry Groensteen’s name above, but it doesn’t appear in Lecigne’s text.) We know nothing about who are the publishers and artists that he’s criticizing. Maybe he didn’t want to hurt anybody’s feelings? Maybe he didn’t want to attack all mainstream artists, but just a few?…

By the way: no one mentioned what I think is the most interesting part of Lecigne’s text. He tries to answer the question: what is an auteur?

According to him Tardi is an auteur in “La bascule a Charlot” and he isn’t in _Adéle Blanc-Sec_. I couldn’t agree more and I would add another example of my own: Guido Buzzelli is an auteur in _Zil Zelub_ and he isn’t in _Nevada Hill_.

I’m playing on easy mode, sorry! I will let “difficult” and “impossibly tough” modes to another occasion…

“Everything is worth studying in academy these days (I’m just stating a fact, not criticizing or anything…), but this doesn’t lead to the reverse conclusion: everything worth studying has aesthetic worth.”

Well, sort of…but the everything worth studying bit leads almost inevitably to claims which look awfully like arguments for aesthetic worth. To take a case near to my heart, if you look at slasher films and you say, well this is dealing with these issues in this way, and it is structured in that way, and it creates its effects this way — you’re talking about aesthetics.

It’s true that part of the way the academy talks about aesthetics is by saying, “well, value judgments don’t matter.” But part of the way is by saying, “these ignored things are actually aesthetically valuable and here’s why.”

“1) it was guilty of amalgamation (which is against the championing of high aesthetic standards)”

But I would argue that claiming that personal work is superior to commercial work is also a process of amalgamation (you may well think this too?) Whether you’re deciding on the basis of medium or on the basis of production methods, the point is that you’re not judging case by case.

I also actually think that the demand for judgment is maybe given more importance than it ought to be. How a critic values a work certainly matters and should be part of a response…but if that’s all there is it’s just handing out stars, which is a fairly boring way to do criticism.

domingos, re: “He tries to answer the question: what is an auteur?” where did lecigne say that? maybe i read the essay too fast but i couldn’t find anything like it anywhere. in fact, it seems like lecigne’s view of the author is quite relativistic & historically-based, as he points out that the word means different things in different eras (& that throughout time the same meaning of “author”/”artist”/etc. has been embodied in different words.)

rereading lecigne, in fact, it just seems to me like i’m going through a completely different essay than the one domingos describes, one that is a lot less clear-cut in its definitions & attitudes anyhow.

Noah:

Take cultural studies, for instance: a scholar may study racist depictions in comics or fan culture. Aesthetics aren’t that important in these papers. Or the study of reception: what matters is what readings are being made and for what purpose. If the readers are reading trash or not it’s irrelevant.

That said I wish I was that eloquent more than 10 years ago when I naively addressed the Comics Scholars List trying to say exactly what you say above.

There’s another variable on the equation that’s independent of any particular academic: academia is a powerful legitimizing machine. Whatever academia studies must be great, right (that’s the pop perception)? On the other hand, if the academic goes too far off what common sense says it’s great (comics are definitely out) articles may appear on the mainstream media about “those wacky academics.” That’s the origin of all those “Bam! Pow!” articles we know and love.

I agree with everything you say in the last part of your comment. I said that the _Journal_ was guilty of amalgamation, but I didn’t say how. I would love to give you examples, but I can’t do the research right now. Because of Suat’s review of _Blacksad_ I remembered a positive review of _Torpedo_! What’s lower than that? (An incompetent, unprofessional comic instead of just a misogynistic one?) If you put it on the base and Tsuge, for instance, on top, you have the amalgamation I talked about. It happened because there never was a strong editorial policy. That’s great because, has I said above: *my* comics journal would sink in no time at all. As Suat put it, the masses don’t want to be challenged and they like a: “dogged adherence to soporific storytelling conventions and […] one dimensional portrayals of evil[.]”

David:

Lecigne does a very superficial and rushed diachronic description of the artists’ status. But his goal is the present (his present): “the modern phase: the creator.” I agree that he mentions a few problems, but he also adds: “It’s out of place to solve such long and old interrogations.” I agree that, after taking a relativistic stance (the idea of “artist” is not ahistorical) it’s not very clear if he accepts modern views of artists as avant-gardists (“the creators”) or not. I bet that he does though. Here’s what he says about Tardi: “Tardi is in a schizoid position: a personal performance may coexist […] with an alimentary performance.” He says that Tardi transferred some of his personal discoveries to his _Adèle Blanc-Sec_ series (which he labels “relatively normalized”). Throughout his text an idea of the auteur as someone who experiments with the form in a personal way is opposed to everything that’s stereotyped and formulaic.

“there never was a strong editorial policy. ”

One of the things I liked about the Journal was that, while Gary had a strong point of view obviously, he also was very catholic in what he would allow other people to say from his magazine. I see that as broad-minded rather than shilly-shallying — though you may well be of the mind of that old Louvin Brothers song, “Broadminded is spelled S-I-N.”

Well Noah, I think that there’s a place for everything, even _Wizard_. The problem is the mixing up of the languages. When we name things wrongly.