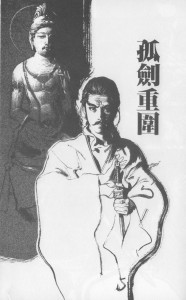

A few weeks ago, I came across a website advertising the “imminent” release of an English version of Ma Li and Chen Uen’s Abi Jian (literally Abi-Sword). It is sometimes forgotten that there exist a very commercial aspect to comics in countries outside the Americas, Europe and Japan. This happens to be just such a comic, notable for being one of the most revered Taiwanese comics in the wuxia genre.

The comic (which in its collected edition of 2 volumes amounts to about 500 pages) was serialized between the years 1989 and 1990 is based on a story by the author, Ma Li. I haven’t read the original novels but on the basis of this two volume adaptation it is of a piece (though somewhat less distinguished) with some of the primary works in the genre.

Among these, the most popular must be the novels of Jin Yong whose books include the Condor Trilogy and The Deer and the Cauldron. The characters of the former work might be familiar to Western readers through Wong Kar Wai’s The Ashes of Time. Wong, like many Chinese, is an aficionado. I am not. But these works have stood the test of time and have inserted themselves so thoroughly into Chinese popular culture that each generation of television viewers has been treated to new adaptations of the same stories. A situation much like the Arthurian tales then, just not quite as venerated by tradition or high culture.

Which brings me back to Ma Li’s Abi Jian. The first volume consists almost entirely of back story, a recitation of the tragedies and misdemeanors of an earlier generation which will impact the protagonist (Wu Sheng) who is still a child as the story begins. Mind you, I spent a while looking online for someone who might have done the job of summarizing these books for me but to no avail. So a somewhat half-hearted synopsis follows.

The story begins with a father (the leader of an honorable sect) and his illegitimate child (Wu Sheng). The child is the product of an adulterous relationship between the sect leader and his best friend’s (Shi Feihong) wife. Shi discovers the affair following the birth of his wife’s child; a mark on the baby’s forehead, a trait which he shares with his biological father, being the telltale sigh. Shi accidentally kills his wife in the altercation that follows this revelation. Grief stricken, he allows his brother to leave with the baby.

The events of the comic begin a decade after these events. The child is now 10 and is kidnapped by a rival sect in the first chapter of the adaptation. Shi Feihong, who had been in deep mourning following the events described above, has emerged in a more monstrous form, wielding a new sword technique called the Abi Jian technique. In so doing he has clawed back all the losses his sect has sustained at the hands of rivals following the events and confusion which followed the expulsion of Wu Sheng’s father. This sets the stage for a tale of ambition, murder and revenge, the child Wu Sheng suffering abuse at the hands of Shi before attaining a kind of martial enlightenment towards the close of the second volume in the series. It’s a time honored plot in the tradition of Jin Yong’s Heaven Sword and Dragon Sabre. The idea of treasure swords (or swords of immense power) and miraculous martial arts techniques will also be nothing new to readers of fantasy or movie goers who have supped on Ang Lee’s Crouching Tiger Sleeping Dragon and films from the Shaw Brothers Studio.

The first volume of Abi Jian is rather slow going with the hero, having suffered through various indignities and hardships at the hands of Shi, barely beginning to acquire his skills at the end of its 250 pages. The second volume sees Wu Sheng on the cusp of realizing these skills having encountered an ancient guardian, a rather common trope of wuxia stories where sudden surges in power are the norm (just as you might find in many modern shonen manga). Chen Uen never completed his adaptation of the novel and the comic stops short just as it is about to get interesting.

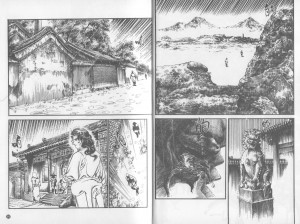

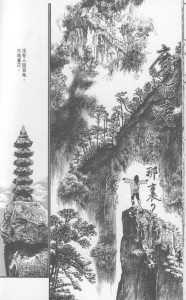

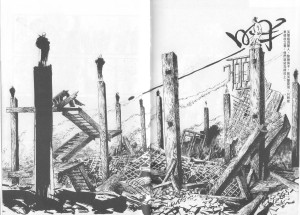

Now you could be excused for asking, “Well, why bother?” I have no intention of arguing with this sentiment but if there is an answer to this question, it would lie in Chen’s art. The idea of spending two years of your life on 500 pages of comics may seem quite reasonable to Western minds but it’s a slow slog as far as the Chinese comics industry is concerned. Chen poured his heart and soul into this one. This is an early title in Chen’s oeuvre and the first few chapters show him wrestling with the idea of combining traditional Western illustration techniques, Chinese brush painting and Japanese manga routines into a unique whole. This meant meticulously scratching out the folds of this traditional mountain landscape (“Western” illustration techniques applied to a very traditionally Chinese subject matter called, shanshui or “mountains and waters”)…

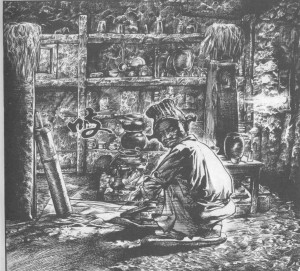

…investing time in throwaway end hooks like the interiors of this cannibal’s den…

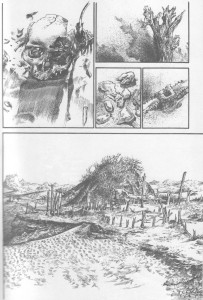

…patiently developing mood in this desert scene setter (some of the fine shadows here apparently laid down with a toothbrush)…

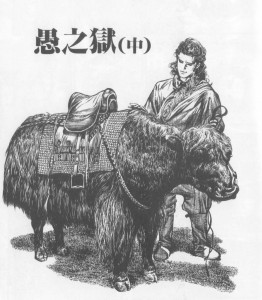

…and meticulously inking this ox for a chapter header.

It’s all a bit showy and clearly reflects a young artist eager to demonstrate his skills. Even so, the results are not wholly satisfying. There were still deadlines to be met and Chen was still playing in traditional areas of expertise. The cannibal’s face is appealing ragged and ridged but the interiors of his home still look somewhat two dimensional, the kitchen implements lacking that solidity we find in the best illustrative work. In these realistic renderings, he shares some similarities with mangaka like Hiroaki Samura (who also regularly employs highly finished pencil work) and Ryoichi Ikegami (prolific, highly photo referenced, somewhat titillating and less versatile).

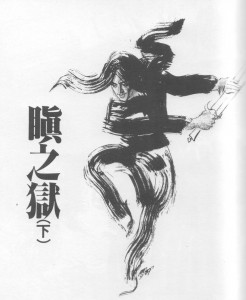

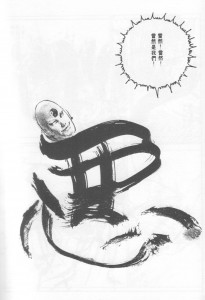

Chen is much more interesting in the way he deploys traditional Chinese brush techniques (center brush, dry brush, split brush, washes etc.) in the creation of accessible mainstream material; that same strange juxtaposition of the refined and the deeply commercial which painters and watercolorists like Jon J. Muth, Kent Williams and George Pratt brought to comics; an effect sometimes admired but just as often reviled for its opposition to traditional cartooning. The Chinese brush would appear to be a more natural segue from traditional cartooning and Chen’s calligraphic strokes, those vigorous movements used to define the characters in Cao-Style calligraphy, are sometimes fastened on to the individuals themselves…

Note, how the figure of Wu Sheng mimics the the first character of the title in the image above. The nature of the individual is fully embodied in the strength of Chen’s brushstrokes as it is in the page below where the character used to form the body of the itinerant monk is that of the Chinese word for evil.

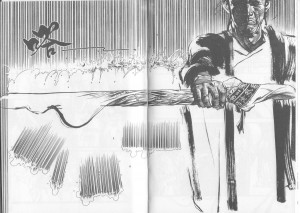

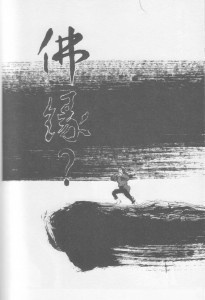

At other times the calligraphy is in the form of an existential shout. The mountain, in contrast to the more detailed earlier image (fourth from top), is presented by a brush stroke drawn back and forth across the page.

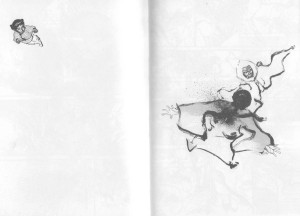

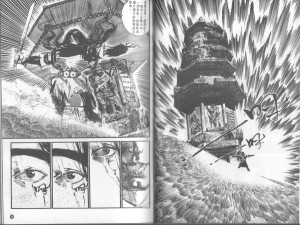

These practiced and minimalistic brush strokes are used to accentuate the more dramatic moments in the text. The following double page spread depicting the death of Wu Sheng’s father at the hands of Shi is another instance of this.

No surprise then that kids expecting stiff Jademan-quality hack work got immense pleasure from Chen’s craftsmanship back in the day. It might even have been inspirational, this grafting of the traditional to the modern, this utter dedication to bringing out the marvelous theatricality inherent in the genre.

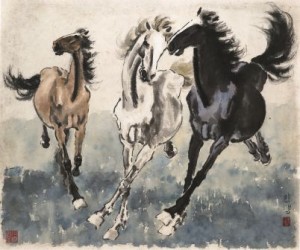

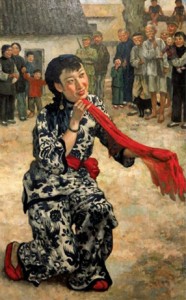

Of course, Chen was only bringing something new to wuxia comics and not to Chinese art in general. The artist Xu Beihong (1895-1953) was certainly the most prominent traditional Chinese brush painter who, having knowledge of both oils and Chinese ink, attempted to meld the differing traditions of Eastern and Western art.

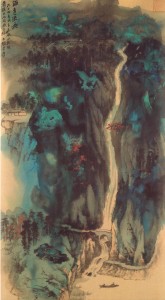

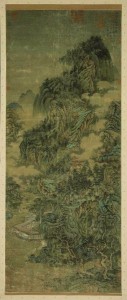

Chen’s landscapes could never be compared with those of a twentieth century master like Zhang DaQian…

[A splashed ink-color painting by Zhang]

[A famous forgery by Zhang]

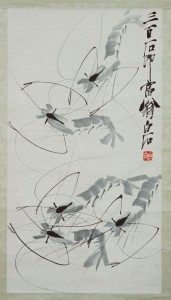

…nor does his brush hold that elegance, liveliness and simplicity seen in the paintings of Qi Baishi, much less the great masters from the past.

Chen has since moved to Japan to produce his comics and has even taken up residence there. The writer of a short career retrospective suggests (quoting a Kodansha spokesperson) that there are two reasons why a Japanese manga company would hire a foreigner to draw for them. One is if the Japanese readership enjoys his work and the other is if there are no Japanese manga artist who can draw like him.

[Above, a conglomeration of all 3 influences in Chen’s art]

It’s a bit of hyperbole to be sure and Chen’s work is distinctive enough that I imagine it can’t be a very popular style in such an insular market. It also sounds like something that was said of the artist when he was in the thick of his fame (he won a Japanese Cartoonist’s Association Award in 1991 for his comic, Heroes of the East Chou Dynasty). Sadly, Chen hasn’t always maintained that spark of originality found in these early works. Nonetheless, Abi Jian remains as good a way as any to experience a genre which remains entrenched in Chinese comics.

I think I may well like Chen’s work more than you do, at least from these examples. The use of the brush painting for pulp adventure is exciting and ridiculous in a way that’s really surprising. It’s certainly much fresher than the two examples of Xu Beihong’s work you provide, which seem (to me at least) like a fairly boring and sentimentalized lowest common denominator mish mash of eastern and western, jettisoning the more interesting aspects of both.

But it’s possible that it’s easier to appreciate Chen’s work if you aren’t actually reading the books? The plots sound uninvolving, I have to admit….

I am not a great admirer of Xu’s painting so you won’t get a defense of his work from my direction. But he’s a “big” painter as far as twentieth century Chinese art is concerned. That painting with the girl (“Put Down Your Whip”) sold at Sotheby’s for $9.2 million in 2007. The one with the horses is a pretty traditional Chinese brush painting. Xu is famous for his depiction of horses and drew a lot of them.

There’s not much to admire as far as the plot of Abi Jian is concerned. It’s as if you read the first 10 pages of a pulp novel – can’t tell one way or another since the project was never completed. All I can say is that it’s not as good as Jin Yong’s masterpiece of the genre, “The Deer and the Cauldron”.

Thanks for sharing! The pages that are more heavily reliant on the drybrush are really striking and dynamic. I’m not as enthused about the last spread at the bottom….

Seeing it at larger size definitely highlights the flaws. The use of typical manga speedlines doesn’t sit very comfortably in that image.

Do you have the Chinese name of this title? I am in Taiwan and would like to pick it up, but can’t get too far with the English. Thanks for the introduction and review!

Here’s a link to the book at Amazon.com China. Title in Chinese characters in bold at the top.

Thanks a lot!

Thanks so much for this review. I think it’s a bit unfair to compare a cartoonist’s work to Qi Baishi and other all-time greats- it’s like saying R Crumb doesn’t quite measure up to Picasso. Still, very helpful review.

Are there any other current artists from Mainland China or Taiwan you would recommend?

You mean modern day Chinese cartoonists? I’m still searching for someone who is consistently interesting. Maybe you’ve heard of some? As for older cartoonists, I presume you’ve heard of Feng Zikai? Probably the most important Chinese cartoonist of the 20th century.

It’s definitely unfair to compare Chen to Qi Baishi or Zhang Daqian. Just wanted to make it clear to readers not familiar with Chinese brush painting (this being an American comics blog) that Chen’s work isn’t the height of mastery as far as the technique is concerned.

Suat-

Any idea why this hasn’t been published in English yet? The Locus-International website talks about it as if it will be published any minute now, and in other places as if it was published last year, but I can’t find it for sale anywhere. Just wondering if you wrote to or spoke to anyone at the company, or have any idea what happened.

Hi Sean, I’m afraid I have absolutely no information on the book. In fact, I had assumed it was never published (lost rights? never had rights? bad market? no distributor?) until your comment above. Could just be a simple publishing delay.

As you can see, they are seriously cheap from Amazon.com China (US$6.50) for the set. That’s one option. I’ve ordered from them before (though not comics) and they are reliable but they may or may not accept U.S. credit cards. They also carry the best comics adaptation of The Romance of the Three Kingdoms though only the economy version is available (poor printing; hence the price $17.50). The collector’s version is out of stock. In Chinese unfortunately but this is a true classic of Chinese comics. Also, a Feng Zikai “Best of” collection. Can’t vouch for this one because I only own the complete collection which I can’t find on their site. That’s enough shilling for Amazon I think…