For this column, I’d like to return to the subject of comics criticism. A while back, HU hosted a Popeye roundtable, which raised some interesting general questions, but seemed to stop from lack of enthusiasm before it went very far. Not being in a position to contribute at the time, I would like to resurrect it for the purpose of raising a number of issues pertaining to how we talk about comics and art.

Noah in his ambiguous essay on E. C. Segar’s strip expresses frustration at what he perceives to be its shallowness:

Though I enjoyed the energy of the drawing, and the Sea Hag and Goon provided some evocatively creepy moments early on, the limited range of the humor, and its empty-headedness, quickly becomes numbing. Wimpy is lazy, Wimpy eats a lot, Popeye is noble, defends the underdog, and always wins.

Robert, in his piece, which references a series of earlier, excellent reviews on his own site, concludes that the strip is “largely of historical interest”, writing:

The challenge I gave the work was for it to transcend that description. It occasionally did; there were flashes of satirical and absurdist genius every now and then. “The One-Way Bank” storyline from Volume II and the finale of “The Eighth Sea” storyline from Volume III stood out, and I was especially taken with Volume II’s “The Nazilia-Tonsylania War” — its treatment of state and military folly ranks with Dr. Strangelove (almost) and Duck Soup. (No pun was intended with the name “Nazilia,” by the way.) However, Segar was generally far more enamored with farce and slapstick for their own sake than he was with satire. That greatly limits the appeal of his work, at least for this adult reader. Farce and slapstick that don’t connect with anything deeper are best in small doses; they tend to wear out their welcome fairly quickly.

So the strip is less than great because it is simplistically conceived and primarily concerns itself with slapstick and farce, only rarely ‘transcending’ these. For Robert, this happens when it becomes satirical, because that somehow connects ‘deeper’ than mere laffs.

This seems to me a holdover from modernist conceptions of aesthetic value that privilege the framework provided by the ‘high’ arts. Robert even spells out this bias:

No reasonable person would consider it on the level of Faulkner, Kandinsky, or Jean Renoir’s work, but it looks right at home when viewed alongside the efforts of Mae West, W.C. Fields, and the Marx Brothers. I have nothing against the popular-entertainment standard for determining “good” comics, by the way. If a comic entertains people, it’s doing its job. And if it’s entertaining people to the extent that it becomes a pop-culture phenomenon, which Segar’s Popeye certainly did, then it’s doing its job terrifically well.

…But it still isn’t as great as Faulkner, Kandinsky or Renoir. Invoking the consummate elitist Harold Bloom’s definition of the canon as what should be taught in our schools, Robert judges Popeye out. But why? He has himself conceded that it gripped more than one generation of readers and became a pop-culture phenomenon. Isn’t that worth teaching in schools? And what about those great humorists cited? Irrelevant to the understanding of our culture?

My intention here is not to claim that Popeye – or Thimble Theater if we want to be correct – is the equal of the best high art had to offer at its time (conversely I’m not saying that it ain’t either). What I am saying is that it will necessarily look impoverished when judged in the framework of high culture, and that I find such a yardstick unhelpful in assessing its qualities — qualities that clearly resonated widely and persistently. Although we have now for several decades described our times as postmodern, with everything that entails, the elitist legacy of modernity is amazingly hard to shake.

Noah recognizes this, essentially framing his dismissal of the strip as personal preference. He compares with another low-culture medium, which has received even less high-culture acclaim: television, concluding that,

…what is and isn’t considered art is really arbitrary. Comics critics have spent a lot of energy for the past decades trying to get comics accepted as high art. They’ve had definite (if not unqualified) success, and now even frankly pulp, unpretentious works like Popeye can be put up in galleries, given lavish reissues, and hailed as canonical examples of the form.

I would guess that someone like Noah, who spends a fair amount of energy as a critic acclaiming the qualities of some of the most commercial iterations of contemporary pop music, would be unsatisfied with the kind of high-culture point of view brought to bear on comics by some of its more assiduous critics at this current, mercurial juncture in their history.

Having long regarded hip hop as one of the most inspiring cultural manifestations of the last 30 years, I sympathize. It has been interesting to watch its fortuna critica in the cultural establishment as it has evolved: regarded initially as a fad, its staying power has come to be recognized and it is now classified as a legitimate musical genre, but it still isn’t considered an art form on the level of, say, rock music. “Gangsta Gangsta” by N.W.A simply doesn’t cut it when measured by the yardstick of “Like a Rolling Stone”, but it is undeniably a hugely resonant piece of work, every bit as influential on the generation from which it sprang.

Similarly, at the time of Thimble Theater, surely ‘no reasonable person’ would consider something like ragtime or jazz on the level of opera. Yet, today, these forms and their progeny are regarded as entirely respectable art forms, capable of greatness akin to that achieved in classical music. Music unites us in ways that other art forms don’t, and we seem to be more receptive to “shallow” qualities there than we do in literature, fine art, or even comics. Perhaps this is not so surprising, since music generally is less cerebral than those forms, making us appreciate — and intellectualize — our emotional and visceral responses to a higher degree.

And actually at least one perfectly reasonable person did consider ragtime and jazz, and with them a whole range of other popular forms such as vaudeville, the movies, and yes, comics, on the level of high culture. A cultural critic and New York correspondent of T. S. Eliot’s Criterion, his name was Gilbert Seldes (1873-1970). In his precocious defense of popular culture, The Seven Lively Arts (1924), he wrote:

If you can bring into focus, simultaneously, a good revue and a production of grand opera at the Metropolitan Opera House, the superiority of the lesser art is striking. Like the revue, grand opera is composed of elements drawn from many sources; like the revue, success depends on the fusion of these elements into a new unit, through the highest skill in production. And this sort of perfection the Metropolitan not only never achieves — it is actually absolved in advance from the necessity of attempting it. I am aware that it has the highest-paid singers, the best orchestra, some of the best conductors, dancers and stage hands, and the worst scenery in the world, in addition to an exceptionally astute impresario; but the production of these elements is so haphazard and clumsy that if any revue-producer hit as low a level in his work, he would be stoned off Broadway. Yet the Metropolitan is considered a great institution and complacently permitted to run at a loss, because its material is ART. (pp. 132-133)

Lest he be dismissed offhand as the kind of contrarian philistine such statements might evoke in us today, I hasten to supply the following; during a visit to Picasso’s studio in Paris, he was shown a fresh canvas by the master, which prompted in him a synthesis:

I shall make no effort to describe that painting. It isn’t even important to know that I am right in my judgement. The significant and overwhelming thing to me was that I held the work a masterpiece and knew it to be contemporary. It is a pleasure to come upon an accredited masterpiece which preserve its authority, to mount the stairs and see the Winged Victory and know that it is good. But to have the same conviction about something finished a month ago, contemporaneous in every aspect, yet associated with the great tradition of painting, with the indescribable thing we think of as the high seriousness of art and with a relevance not only to our life, but to life itself — that is a different thing entirely. For of course the first effect — after one had gone away and begun to be aware of effects — was to make one wonder whether it is worth thinking or writing or feeling about anything else. Whether, since the great arts are so capable of being practised today, it isn’t sheer perversity to be satisfied with less. Whether praise of the minor arts isn’t, at bottom, treachery to the great. I had always believed that there exists no such hostility between the two divisions of the arts which are honest — that the real opposition is between them, allied, and the polished fake. (pp. 345-346)

I think we could do worse than take a cue from Seldes’ notion of the ‘lively arts’ in our current reassessment of comics as cultural phenomena and art. About the comic strip:

Of all the lively arts the Comic Strip is the most despised, and with the exception of the movies it is the most popular. Some twenty million people follow with interest, curiosity, and amusement the daily fortunes of five or ten heroes of the comic strip, and that they do this is considered by all those who have any pretentions to taste and culture as a symptom of crass vulgarity, of dullness, and, for all I know, of defeated and inhibited lives. I need hardly add that those who feel so about the comic strip only infrequently regard the object of their distaste.

Certainly there is a great deal of monotonous stupidity in the comic strip, a cheap jocosity, a life-of-the-party humour which is extraordinarily dreary. There is also a quantity of bad drawing and the intellectual level, if that matters, is sometimes not high. Yet we are not actually a dull people; we take our fun where we find it, and we have an exceptional capacity for liking the things which show us off in ridiculous postures — a counterpart to our inveterate passion for seeing ourselves in stained-glass attitudes. (p. 213)

Seldes doesn’t mention Thimble Theater, and couldn’t have known Popeye (on account of he hadn’t been born’d yet), but he regarded highly its neighbor in the New York World, Krazy Kat, whose creator George Herriman he considered one of the two genuine artistic geniuses in America at the time (the other was Charles Chaplin). In his famous essay on that strip, he wrote:

With those who hold that a comic strip cannot be a work of art I shall not traffic. The qualities of Krazy Kat are irony and fantasy — exactly the same, it would appear, as distinguish The Revolt of the Angels; it is wholly beside the point to indicate a preference for the work of Anatole France, which is in the great line, in the major arts. It happens that in America iron and fantasy are practised in the major arts by only one or two men, producing high-class trash; and Mr Herriman, working in a despised medium, without an atom of pretentiousness, is day after day producing something essentially fine. (p. 231)

Granted, Krazy Kat has received greater high-culture recognition than any other strip of its day, and seems more effortlessly to accommodate a fine arts perspective, but I don’t see why one couldn’t formulate something along similar lines for Thimble Theater. Noah suggests that one might compare the strip with the cinema of Buster Keaton, which strikes me as particularly instructive:

Keaton’s work rightly occupies an important place in the cinematic canon, despite it being similarly resistant to the kind of interpretative framework that eschews slapstick. As the New Wave filmmakers recognized, however, his auteurial presence is acutely felt throughout his work, and it gives us a highly original, fatalistic and uncannily comic conception of depersonalized action in a world of strange, fickle serendipity.

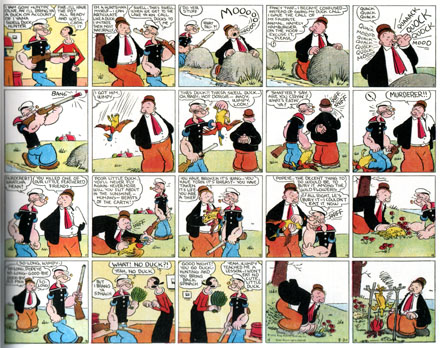

Now, let’s look at fairly typical, self-contained Sunday page from Thimble Theater (sep. 30th, 1934):

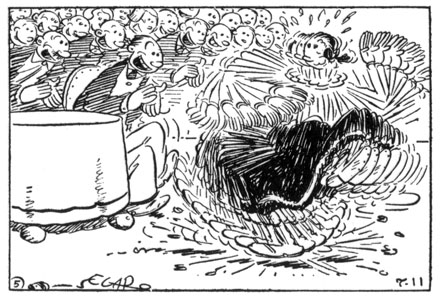

On the surface, it delivers a straightforward gag pitting, as is so often the case, Popeye’s morality against Wimpy’s lack of same. But Segar is anything but a utilitarian gang man; he proceeds like a cartoon behaviorist, generously packing in as much character detail and humorous instance to create a highly seasoned repast, all the while unfolding a strongly intuited moral ethos.

Watch his unaffectedly plump line and vernacular wit unfold across the page: Wimpy insinuating himself into the frame and the duck hunt, bodily/verbally; his mention of his favorite animal, “hamburger on the hoof”; the manner in which he splays his three surplus fingers while pressing his nose to quack (and, inevitably, to hamburger moo); his poker face registering the hit, turning to sniff; the derision on his face against Popeye’s soon-to-vanish irascible scowl; the silent burial bookending Popeye’s contrition, Wimpy empathetically yet efficiently settling the mound; the exchange: “WHAT! NO DUCK?!” — “Yeah, no duck”; the unchanged expression on Wimpy’s face as he kneels caninely to exhume the duck with speed, his coattails waving; it remains unchanged as he sits at the end, counter to the left-right flow, roasting the kill.

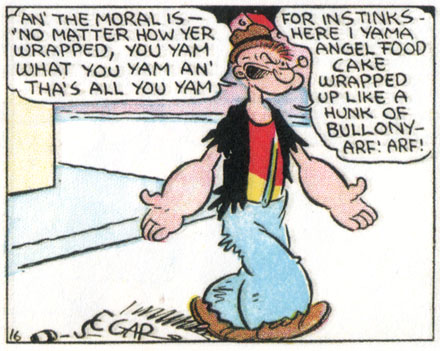

Clear in presentation, yet richly studied, this sequence is a perfect summation of the profane reality of Thimble Theater. A true comedic hero, Popeye is pugnaciously selfless in a world governed by selfishness. He always restores order around him (often, disturbingly, by violence), but is simultaneously given enough of a tragic edge — his morality is rarely reciprocated — to keep us involved. As with Keaton, there’s a fatalistic undertone to his and, by its frequent extension to the rest of the cast, the strip’s indomitable catchphrase: “I yam what I yam, an’ that’s all I yam!” It’s trenchantly inspirational and it is great fun, so why can’t it be great art?

Part of the answer, if one compares with cinema, is that it has taken comics much longer to expand its field beyond a fairly restricted set of idioms and genres, all of which are candidly low culture. It hasn’t had its James Agee, though people like Donald Phelps, R. Fiore and Art Spiegelman have done their best in recent decades; they haven’t had their Raymond Rohauer and have only recently begun experiencing comprehensive restoration and republication, and they haven’t had their new wave until now.

Which brings us to the matter at hand: this is a time of redefinition for comics, which is not only manifest in contemporary cartooning, but naturally extends back to encompass its history. Neglected by critics and historians, and forgotten even by most cartoonists, the classics now demand our attention for what they teach us about their time and the evolution of the form, but ultimately also as works of art. Though it is surely healthy to assess comics in the expanded field of cultural production being opened up as distinctions between high and low are collapsing, to not cut them any exceptionalist slack, it would seem ill advised to judge them according to antiquated systems of hierarchical exclusion.

PS — Because Noah mentioned them as part of his high-low concordances, I can’t help bringing in the Coen brothers here. While it is correct that they are becoming canonized as directors, it is remarkable that their best loved, and arguably best though not most critically acclaimed film, The Big Lebowski, is so unabashedly shallow. It totally fails the modernist test as a work of art, and yet there it is, and it’s glorious.

Squint, imagine some more punching, and it might almost play at the Thimble.

Hey Matthias. This is a great post. Lots to think about.

I’d sort of quibble with some of the lines you draw. I think Hip Hop is more critically established than you suggest, and Dylan less so — as a result I don’t think the distinction you make there really applies. Hip hop is pretty thoroughly lauded at this point, I’d say — if not NWA, then certainly PE.

Similarly, jazz had by the 30s at least a lot or pretensions. That’s obviously the case for Ellington, but it’s even true for someone like Louis Armstrong or other jazz musicians, who had a quite sophisticated aesthetic involving improvisation, spontaneity, and (in many cases) subcultural pride. Comic creators had nothing comparable, I don’t think. In addition, jazz’s bona fides were ignored and denigrated for reasons that had a lot to do with racism. For all those reason, I think comparing jazz to comics is something of a red herring.

I also think the Big Lebowski is way more critically engaged than you say it is. I haven’t seen it for a while, but my memory is that it had a lot to say (and quite consciously) about class divisions. It seems a lot more tied into high art issues than Popeye.

Which was sort of my (ambivalent) point about Popeye. It’s really an almost completely unpretentious strip. You talk about the morality and order in that strip above, but that morality and that order are really intellectually pretty banal; there’s not anything there but sentiment and appetite. That’s not the case in the Big Lebowski or Krazy Kat, which both deal with more complex themes in a more self-conscious manner. (I don’t know Chaplin or Keaton well enough to speak to them, unfortunately.)

I have trouble really disliking or even denigrating Popeye because it doesn’t do more, though, because it so clearly isn’t trying to do more. It is skillful and lively, and since that’s so clearly what it’s offering, I don’t see any reason to sneer at it. It is kind of like a pop song; it hits you or it doesn’t.

I would say that the problem with something like Popeye in terms of where comics is at now is tied in to your discussion of comics experiencing a New Wave. I think obviously comics is shifting in aesthetic status at the moment, and those changes might be comparable to New Wave cinema. What there isn’t, though, is the kind of critical renaissance that happened with the New Wave. The reappropriation of strips like Popeye therefore seems to happen in a kind of critical vacuum. Genres aren’t reexplored and emptied out (as happened in the New Wave) so much as canonized and embalmed in nostalgia.

Or, if that sounds too harsh, maybe I could just say that there seems to be a fair amount of critical confusion about how the older work relates to newer work. I think you see that in Ben Schwartz’s Best American Comics Criticism, for example, which makes some effort to be about the lit comics revolution, but then throws in lots of pulp and genre work without really making a connection (or even seeming to realize that you would need to make a connection) between the two.

I think you’re actually struggling in many of your posts here to do that critical work yourself. I think it works better here, where you’re basically making a plea for low art by turning it into “lively arts”, and contextualizing comics with other pulp or non high brow work. Things get trickier with something like Crumb’s Genesis, though — a work which obviously has high art pretensions while being indebted to low art traditions. I think you essentially try to argue that it’s lively art roots bring something to the table that strictly high art traditions lack (or more precisely which high art traditions occasionally conveniently forget about.) The problem is that I think it’s hard to argue that Crumb (or the new comic creators in general) manage to use their lively roots as effectively as filmmakers have used theirs over the years….

Thinking about it a little more; the older material seems to usually be legitimized by either amalgamation with newer high art comics (as Domingos would put it) or through personal nostalgia as part of some kind of literary coming of age narrative. The use of low art for high art as in Breathless or something like Raising Arizona seems to be hard for comics to manage at the moment without either a lot of anxiety (as in Chris Ware), fairly straightforward repetition (as in Richard Sala), or in an explicitly humor context (as in Michael Kupperman — presuming he should be seen as high art.)

Or that’s my sense anyway.

Noah, thanks for commenting!

The quibbles you have with my comparisons are debatable — I think we’re talking more degree than kind in any case. I mean, sure there was a subculture involved in appreciating jazz in the 30s, and a lot of professional pride, but it was hardly accepted as a canonized art form.

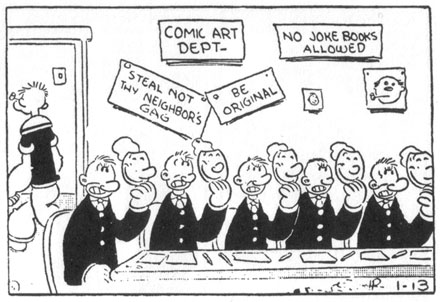

Also, you’re not correct in saying that cartoonists didn’t have professional pride — sure, the field was populated by hacks, but people like McCay, Herriman or Segar clearly had it in spades — for the latter, just read the “Puddleburg Weekly Splash” story, from which the image of the masked cartoonists above is taken. Also, comics afficionados *did* exist at the time — Seldes was one of them.

As for hip hop, I must disagree. Yes, Public Enemy is respected, but they are also the group that is the easiest to reconcile with the high culture standards established within rock music. It’s much harder to find a high cultural consensus on NWA, and never mind Li’l Wayne or Gucci Mane. The genre is far from as respected *as art* as rock music.

The Big Lebowski critically engaged in class divisions? Where??? It’s almost entirely pastiche, which I guess is the most obvious place where you could make a typical high culture argument for its value — its postmodern sense of play. But really, what makes it great is the sheer originality of the characters and world it creates it, plus the fact that it’s hilarious.

Which is my point: you’re right that Popeye doesn’t have high art pretensions. That’s one of the great things about it in my book (not that I mind such engagement in other comics). The point I was trying to make was that I don’t see an obvious reason why such such aspirations are prerequisite of art, or at least great art. I mean, you made much the same point yourself in your original post — why is that great Abbot and Costello sketch not art?

To me originality, imagination, the ability to transport the audience, intelligent application of one’s skills in service of one’s premise, and — not the least — the ability to be consistently funny count for as much as anything else when I encounter a work. The problem is that when united in certain constellations, often in the service of entertainment, of comedy, they’re often hard to intellectualize and I guess therefore harder to canonize.

I very much agree with you re: your thoughts on the New Wave analogue. It’s obviously not fully workable, but I think there are enough things in common that it’s justified. I entirely agree that useful criticism, from both practitioners and critics, is lacking, though I wouldn’t quite describe the situation as a vacuum. My point, however, is that comics are in a state of flux where these issues are increasingly surfacing both in the comics and criticism. Our responsibility as critics, I guess, is to do the best we can to contribute to a more interesting, constructive or elevating (etc.) discourse.

(I haven’t read Ben Schwartz book — frankly it didn’t seem worth it from the table of contents. Most of the good stuff in there, I’m already familiar with from elsewhere, and Schwartz’ editorial hand seems shaky).

As for cartoonists who process the classics, there are many, and many who do it exceedingly well. You’ve mentioned Ware, who indeed brings a lot of anxiety to the endeavor, but that’s because he’s so conscientuous — his work also happens to be mostly brilliant. Clowes has processed and subverted comics tradition in astonishing ways. David B created as bona fide masterpiece by adapting comics imagery to suit his subconscious. Kevin Huizenga is tapping into the cartoon vernacular of people like Segar very thoughtfully. And the Hernandez brothers have been doing it more effortlessly than just about anything else for decades.

As for Crumb, he’s obviously a major touchstone in this respect, and I agree that there’s a frisson between tradition and his ambitions that doesn’t always work in his Genesis, but as you know I still consider it to be an enormously interesting interpretation of the text.

Whether these cartoonists or their many peers are succeeding as well as their counterparts in film I guess remains to be seen, but I find what’s going on plenty interesting as is.

NWA is tough because they’re so misogynist and violent; it’s analagous to exploitation films, I guess. But groups like PE and Outkast and even Wu-Tang and Biggie and Nas are pretty thoroughly canonical at this point (as rock goes.)

Maybe I need to see the Big Lebowski again. I’ve kind of disengaged from the Coens over their last few films, I have to admit….

“The point I was trying to make was that I don’t see an obvious reason why such such aspirations are prerequisite of art, or at least great art.”

Yeah, I don’t disagree with that. I think at some point though Abbott and Costello or Popeye start to undermine the idea of canonical art — that is, they raise the question of why or whether these standards are especially useful in the first place. (I’m waiting for Domingos and Suat to tell me I’m full of it any moment now….)

A lot of what I wrote in my Popeye piece for the roundtable was rooted in the issues that were raised in the various discussions of Ben Schwartz’s Best American Comics Criticism. They really do need to be understood as a response to and a rejection of what I see as a great deal of undiscriminating callowness on the part of many comics critics. I’m particularly thinking of those who see the embrace certain comics projects have found among critics and readers beyond the comics subculture, and erroneously regard it as a validation of the subculture’s view of itself.

As I stated in the piece, Segar’s Popeye holds up well when considered against pop-culture works that were contemporaneous with it. However, when considered against what have become the canonical works of its time, it comes across as thin and unsophisticated. I’m not faulting anyone for enjoying it; I like a good deal of it myself. I’m just saying that people shouldn’t make more of it than what it is. And it is certainly not one of the great aesthetic achievements of 20th-century U.S. culture.

Hey Robert. That’s an interesting clarification.

Standards are obviously (or obviously to me anyway) variable for different people and different times. You could imagine a hierarchy in which Popeye beats James Joyce or Hemingway or what have you. I think what excites Matthias about comics, in part, is the way that, as they have started to engage with high art, they do seem to have at least the potential of using their history to shake up some standards, or change the way we might think about art.

The stumbling block is that, as you say, comics (or especially comics criticism) often seems more interested in asserting that canonical cache has been attained than in doing anything creative with the distance from the canon. (Or at least that’s my sense; Matthias may disagree.)

Yeah, that’s pretty much it Noah, though basically my impulse here is even simpler — I think some of these low-culture works, whether comics or whatever else, are as great as many high culture works of art.

Thanks for clarifying, Robert — I agree in part obviously, and am not trying to say that Popeye is one of the great aesthetic achievement of 20th-century US culture — very few comics are — but I do not think that has anything to do with its premise, which is in part why I made the comparison with Buster Keaton, whose work I *would rate.

Plus I do obviously think Popeye is pretty great and not at all ‘thin’ or ‘unsophisticated’ — as I wrote, that’s only if you measure it by standards created to assess a different kind of aesthetic aspiration.

And that’s really what I’m trying to say: we can all make our personal lists and they will all differ, but what’s more important is not perpetuating an anachronistic hierarchy of the arts that posits almost a priori certain fairly arbitrary criteria for what should and should not be considered great.

Very nice essay, Matthias — glad I picked today to come back!

Matthias and Noah: I’m curious to know what you think of this recent essay in the London Review of Books.

I can easily agree, Matthias, with a lot of the specifics here, but I’m uncomfortable with the tie you use to bind modernism to “high art”. It allows you to say that the “framework provided by the ‘high’ arts” is exclusively available to creators who privilege modernist aesthetic values — which you seem to define (contra Robert) as cerebral and formally complex. But there are extensive and pluralistic “high art” frameworks now for “popular” art as well, frameworks that also value “cerebral” and “formally complex” elements. Those things in themselves aren’t anachronistic or arbitrary: there are just specific historical senses of them appropriate to now.

I’m not saying that Popeye doesn’t engage those frameworks. I’m just saying that they’re relevant.

A lot of Jazz’s credibility came about because critics in the ’50s wrote about it just like it was classical music. They didn’t say “Brubeck and Monk aren’t trying to make classical music so we have to evaluate them on their own terms”. Instead they paid attention to the ways they took the innovations of those ’30s entertainers and smashed them up against classical standards. Jazz critics embraced those high art standards and transposed them into a blue key.

Replacing that synthetic approach with a subjective one — “not perpetuating an anachronistic hierarchy of the arts that posts almost a priori certain fairly arbitrary criteria” — feels more like your committment is to ridding us of certain types of criteria altogether than to redefining “high” in a way that allows what comics do best to inform our understanding of how art works in general. In all cases, art forms and approaches and aspirations that have been re-evaluated successfully have accomplished that through those conversations with existing, “validated” arts.

Which brings me to why I shared the LRB article because I think it does a good job of explaining the aesthetic limitations of this, not just the ones related to critical reception: Batumann advocates that writers take a position to the history of their art form that is both deeply engaged and desirous of transcending — the position you see in Rauschenberg’s engagement with De Kooning or Pynchon’s with Joyce, and in both cases there was a murderous embrace: a “kill your idols” approach. To no small extent the difference between an MFA approach and a PhD approach is the difference between “appreciative” and “analytical” evaluation — MFAs do study literary history, contrary to what he said, they just don’t study it the same WAY or to the same extent. Batumann’s takeaway point IMO is that the deeper analytical understanding and engagement is necessary to avoiding the programmatic trap.

Comics doesn’t seem to be ready to take that approach, either by critics or by creators, and that leads to a kind of programmatic quality among contemporary art comics, as it does in program fiction (although the program is different in the details). Comics — to its credit — has created an MFA-flavored culture almost entirely organically. But I think as a consequence the limitations that Batuman describes plague contemporary art comics as well. This kind of approach to Popeye — to any historical cartoon — seems like it will perpetuate those problems.

The Big Lebowski is about a depiction of the United States in the late 20th Century where meaningful icons have lost their meaning. I think at least one way to read the movie is that it’s very much ridiculing how America views itself as this hero figure in its foreign policy..?

It’s being narrated by a forgetful Cowboy– it’s not really a subtle image. One of the opening shots is of Bush Sr. spouting nonsense as a justification for Desert Storm– Lebowski even repeats those lines later on– even though it was filmed and released during the Clinton administration.

Plus: The Jew’s not a jew, the kidnapped girl wasn’t kidnapped, the rich guy isn’t rich, Jesus is a pedophile, and the famous writer of macho war tales is some old dude stuck in a contraption, etc. Or the way the heroes and bad guys sort of mirror one another– the bad guys are nihilists; the hero’s the one who doesn’t care about anything…? They’re two angles on the same philosophy.

(Also, I figure Donnie’s probably some kind of Christ figure, but I’m really not great at spot-the-Christ-figure or figuring any of that. There’s usually some spirituality/religion going on in those Coen movies, is all…)

But none of that has anything to do with why the Big Lebowski is good or why people care about it, so who cares. I just wouldn’t call all that many of the Coen movies shallow. It’s richer than some of their movies– though obviously not as much so as others (Barton Fink or especially A Serious Man, say).

Besides that, I enjoyed this essay!

Thanks Abhay! I may have been a bit unfair to the Big Lebowski in calling it “shallow”, but I get the sense that all the cleverness there really is mostly a game for the Coens, rather than an effort to communicate anything particularly profound. For me, this is the case with a lot of their movies, from Miller’s Crossing to the Hudsucker Proxy, and even The Man Who Wasn’t There.

I dunno, your quick reading in any case just goes to show that just about any work that is intelligently put together — Popeye definitely included — will prompt interesting interpretations.

Caro, thanks for your thoughtful comments. I read half that Batuman essay last week, but got stuck. I’ll give it another go tonight and see what I think. It seems though that you and I are pretty much in agreement, with slightly different emphases.

Thanks Matthias — I’m definitely curious to know what you and Noah think of the Batuman (and anybody else too, of course) when you get back to it. I read it originally in the print LRB — and it kept going, and going, and wow is it ever long! — but if you’re reading in print, you might want to check out the website too because there’s a letter from the author of the reviewed book, McGurl. He makes some of the objections I would make vis-a-vis Barth in particular, and I think his qualifications are even more apt for comics than Batuman’s criticism.

But I still think that she picks up on some really important aesthetic limitations of the MFA approach. You and I have been volleying this slight difference in emphasis back and forth for some time, and I brought it up because I think her perspective opens up our old debate in some interesting new ways…maybe thinking about how “Planet MFA” corresponds to “Planet Lit/Art Comics” will make it easier to get through her 8000+ words LOL. Gotta love the LRB for publishing sustained essays like that, eh?

Caro’s back! Yay!

I will try to read the LRB piece. In the meantime I had a couple of questions:

— could you give an example of a high art framework for popular art? I’m just not exactly sure what you’re talking about. (Cultural studies? the New Wave appreciation of genre? something else?)

— Is the kill your idols thing you’re talking about similar to Harold Bloom’s anxiety of influence silliness? And is that really an ideal model?

— Do you feel Dan Clowes *doesn’t* do this? My sense was that you thought he did?

Great post.

I would hold up the work of Mae West, W.C. Fields, and most particularly the Marx Brothers and Buster Keaton against anything Faulkner or Renoir ever did.

Keaton in particular has a particularly consistent (and no less so for it’s hilarity) point of view of modern living, man vs automation and his environment and satire.

I too read his dismissal of Popeye, which could have very extreme critiques within it’s daily dose of laughter, as a personal opinion presented as fact.

gmd–

You know, I’ve never said anything negative or the least bit pejorative about Buster Keaton. As a visual artist, you’d have to go to McCay or Kirby to find someone in comics who’s comparable.

If you’re getting less out of Renoir or Faulkner’s best stuff than I get out of West, Fields, or the Marx Brothers, you have my pity. Keep in mind I think highly of them all. It’s just that, even in Heaven, there are some spheres that are closer to God.

Opinions aren’t facts. All I can do with my opinions is make a strong a case for them as possible. The same is true of any writer. If I’m able, however briefly, to make you think they deserve the credence of facts, I guess I’m doing my job. Thanks.

Okay, I really love that LRB piece. The stuff about Tim O’Brien alone is worth the price of admission — oh and the Sandra Cisneros/Phillip Roth digs…and the Joyce Carol Oates…yeah, the whole thing is gold. I like it so much I can even forgive her praise of This American Life.

I think there are definitely interesting parallels with comics, in terms both of the way she sees MFA writing as a kind of subcultural phenomena; in the fetishization of minority/oppressed perspectives; and in the importance of artistic shame as a motivator/displaced center.

I think Caro though I might be a little more reticent than you are to abstract out a program separate from the Batuman’s particular take on the novel? That is, Batuman’s discussion seems really centered on what she sees as the novel’s history and purpose — that being a contrast between “literary tropes” and “reality” (both in quotes, I think.) She feels like the MFAs focus on oppressed communities has undermined novelistic realism by making reality=oppression in a way that robs the novel of much of its material and of its philosophical bearings. Her goal is conservative rather than agonistic; she’s got a fairly set idea of what a novel should be, and she’s kicking MFAs for not realizing that goal, rather than for failing to use former models to innovate.

So I guess my takeaway would be that this isn’t all that useful for comics, since comics is at a very different historical place from the novel. Among other things, there isn’t a reservoir of Tolstoys and Austens and Dickens to point back to and say, you should really do something more like that. (I mean, you could argue that lit comics have lost the anarchic energy of earlier comics, and I have even made that argument on occasion — but that’s a much more limited and less clearly programmatic argument than the one she’s making.)

Noah–

It’s not surprising that you liked the LRB piece. Both Caro and I immediately thought of you upon reading it. You and Batulman are definitely on the same page with your attitudes towards contemporary writing.

Sigh. I’m so transparent….

I liked it too!

Noah, I didn’t mean to suggest that you could just replace every instance of Planet MFA with Planet Art Comics and have it fit perfectly; just that it’s illustrative to think about where it does and doesn’t correspond. But I don’t think that her general observations about the program are just about novels, although her point about novels is about novels: I think it’s also about the culture and values of the Writing Program.

For example, you bring up the lack of a tradition to point back to, and I agree that makes it harder for us to make critical comparisons comparable to Batuman’s, but I also think that puts cartoonists in a similar place as the MFA writers who invoke the “enabling disablement” for exactly the reason that Batuman points out: like the “disadvantaged” writers, cartoonists are trying to find or create a indigenous voice that they “own” — and as with fiction, there’s both value and limitations in that. The values of the writing program emphasize the upsides – to the point that different upsides, more traditionally literary upsides, are often forgotten.

So I don’t think her complaint is exactly/entirely that program fiction fails to realize her ideas of what a novel should be: I think her complaint is that the writing program does not provide writers with a sufficient awareness of what fiction has been, and that means that program fiction can’t realize it, because they can’t recognize it. It’s not a point about the achievement of a novel: it’s a point about the perspective of a novelist.

By “high art framework for popular art” I wasn’t really thinking of “critical frameworks” in terms of standards that a critic uses for determining value (like Modernism to an academic) so much as just different ways in which creative work can be “sophisticated”, to the artist or the critic: David Lynch was the example in my head, but Pop Art or even some of the “tricks” of the Writing Program (like the way Jonathan Lethem puts a novel together). Those works are “popular” even though they’re not entirely “mass culture”, and the “frameworks” that they participate in aren’t “Modernist” but they do invoke similar formal and philosophical frameworks, and those frameworks aren’t anachronistic or arbitrary. My point is mostly that I don’t think our options are limited to “Modernism” or “taking the work only on its own terms”…

“Program fiction”? Is that to be thought of as a genre? If so, God help us…

I think that at base, she’s pointing out that the program produces fine writing and mediocre books.

The short story is probably the ideal medium for that sort of writing. You can shoot for perfection there, achieve Poe’s “single effect” or Joyce’s “epiphany”.

But the novel should be a sprawling, imperfect, shaggy thing, much like life.

(BTW– if the book under review is as she presents it, we have another example of blind, self-serving, fatuous idiocy from the groves of Academe.)

MFA writing compared to comics? Perhaps the common idea of exceptionalism.

Is it Batuman who wrote ‘The Possessed’ about her discovery of classic Russian literature?

I believe that’s her, Alex.

That was a terrific book.

I’ve now read the Batuman piece and like it a good deal too, although like Noah, I don’t quite see its particular relevance for comics. As he wrote, the medium is in such a different place to the novel that the kind of critical awareness amongst practitioners that Batuman and you are arguing for naturally will have very different results on contemporary comics making. Plus, there isn’t much of a program in comics, excepting a few (still?) rather uninfluential schools (the Angouleme school in France, however, does have some programmatic problems, I think, but I don’t want to get into that right now).

I guess you could argue for certain programmatic tendencies developed organically among the new wave cartoonists, as you mention – the propensity for nostalgia for the 90s generation of American cartoonists is an example – but I’m not really sure I see it as much of a problem for contemporary comics. Autobiography in comics, for example, doesn’t seem particularly attached to “disadvantaged” perspectives, although I guess that depends how you define that. In any case, I think the comics form right now is about as diverse and vital as I could possibly hope for it to be.

Re: ‘the slight difference in emphasis’; this I guess comes down to my being somewhat skeptical of your seemingly rock-solid belief that theoretical or critical awareness in an artist makes for better art. I believe awareness is a good thing, but it doesn’t have to come in that shape or form. Further, as one of the commenters to the Batuman article says, this binary between ‘Planet MFA’ and ‘Planet PhD’ seems reductive and even to the extent that it does exist, I don’t necessarily think privileging the latter is the way forward.

This is not to say that I don’t believe that we couldn’t use greater historical, theoretical, cultural, or other intellectual awareness as comics critics and scholars. We’re obviously still foundering. What I have been focusing on specifically is how this awareness should involve an in-depth understanding of its object – of course there are non-anachronistic ways of dealing with popular art forms, I just don’t see a whole lot of them applied to comics in compelling ways. In general, I retain a distinct sense that the modernist high art framework that I’m talking about still exerts enormous influence in how we perceive and assess art in our culture. There is an academic subset that has developed different approaches to these problems, but they haven’t succeeded particularly well in promulgating their alternative frameworks broadly.

As for your criticism of my advocacy of understanding comics for what they are, instead of measuring them according to principles developed elsewhere, it’s well taken, but I think you’re being a little reductive in your reading of me. I believe deeply in comics being considered in a larger context and am not in favor of “comics exceptionalism” (useful term!). I just believe in a deeper analytical and aesthetic understanding of what comics are and do – it takes longer to build up, but it will make comics critical synthesis into the standards set by other art forms – their particular “transposal into a blue key”, as you wrote – more worthwhile.

BTW, Batuman also wrote this really good piece on graphic novels a while back.

I think with comics autobio the nerd/geek subculture, with its always already assumed status of oppressed other, often stands in for the kind of social oppression that you get in program fiction.

Did folks see Ian Burns’ interview with Johnny Ryan? It sort of reflects on the comics exceptionalism thing in some interesting ways. Johnny talks about deliberately not going to life studies for his Prison Pit book because he wanted it to look to or to reference 7th grade art. So on the one hand that seems like it’s a comics exceptionalism, running away from influences kind of thing that Batuman sneers at for the program fiction — except that looking to children’s art is a thoroughly validated modernist move. Especially since Johnny then goes on to talk about a blizzard of influences, from horror manga to some recent alternative titles to WWW wrestling and exploitation film.

I’d say that a major difference is that there isn’t any sense of shame about his influences or his interests in Johnny’s work. Which actually maybe separates him somewhat from his primary underground influences like Crumb, where there seems to be a lot more anxiety about working in the comics form, or about the use of a children’s medium.

Sorry…don’t know if anyone else is as interested in Johnny Ryan’s work as I am. I need to get that second Prison Pit volume….

Matthias: to take the easy one first: I don’t mean to be against the practice of taking comics as they are, only against the idea that taking them some other way is bad. It’s not strong in your piece, you’re correct — it would be an error to reduce your piece to that, and I disavow anything I said that came across that way! It was always a minor point. But it is there a little bit, this idea that clashing something with one set of aesthetic aspirations against a different set of aesthetic aspirations is somehow “unfair” or misguided or likely to cause a less-than-useful reading.

I think both approaches are vital — ones that focus on close aesthetic and historical readings of comics and ones that smash comics against theory or the different critical and formal projects and achievements of the other arts. I think both will be important to bringing comics more into the cultural conversation about art. So I’m just resisting the implication that “best critical practices” require all critics to avoid, say, modernist values — unless we can really make an argument for why those modernist values themselves are actually bad for comics.

And this is where it’s important for critics to always be thoughtful about our own aesthetics as well as each others: You state that you are “skeptical of [my] seemingly rock-solid belief that theoretical or critical awareness in an artist makes for better art.” I would say that yes, “theoretical AND critical awareness,” with critical awareness being more important than theoretical awareness, does lead to art that I find more satisfying as an adult.

You took Robert to task a bit for the idea that the more “modernist” values are more “adult” and I think that’s a topic we maybe haven’t really explored fully, and maybe we’re in a bit of a rut about it. I tend to agree with Robert, although I like the way Francoise Mouly says it, where she makes it more about “storytelling.” I love this quote where she says “I just feel myself going through the same thing over and over again, whatever the novel or film is, and I just feel myself manipulated into it. I guess I’m just too aware of what’s being done to me to get that sucked into it. And I try to keep some distance from it and therefore I’m not. I don’t feel I’m getting that much from one more novel or one more narrative film.”

I think that’s not that different from Batuman’s point, is it? That the critical historical awareness allows a writer to offer something to a really aware reader that is not manipulative, but wise?

So this is probably why I’m just skeptical when you push back against the subset of values you describe as “Modernist”: I’m not sure what is at stake for you or what you would like to replace that tradition, those expectations. I’m with you on replacing it with something equally rich and wise, but not with the implication — which I agree is reducing you but I want to be extra vigilant against it — that great storytelling and emotion and liveliness and other non-theoretical/critical things will be enough.

So is your criticism of Robert’s measure that he just doesn’t give Popeye enough credit for what it does well, or is it concern that he actually values the “modernist” things more than he values the things Popeye does well? I think the former is a legitimate critical ploy, allowing you to highlight the achievements that his vantage point doesn’t illuminate. (And I think that’s what you’re going for.) But I also sense some of the latter, and that seems like a concept that’s not all that dissimilar to the “working class elitism” that characterizes program fiction.

Batuman’s analysis made me notice that one of the more frustrating things about program fiction to me is how it has narrowed the field to “good writing” (there’s that line about good writing and bad books): modernism — which was one of the last organic, cross-disciplinary artistic movements — embraced technically untrained writers and violations of technical “received wisdom” but advanced fairly high-level positions on emotional as well as cerebral and formalist elements of works, and consequently Modernist works explore an pretty exceptionally wide range of emotional experiences using a wide range of cerebral and formalist tactics, including “writing” that doesn’t fit some programmatic idea of good. So it’s rich. The reason Modernism holds so much sway after all this time is that it’s incredibly rich. Program fiction, as Batuman points out, really isn’t — the values are narrower. And although the values of American art comics aren’t exactly the same as those of program fiction, there’s a comparable narrowness to the cultural value system. This creates a sameness among the work that’s comparable to the sameness among program fiction. So much wonderful high-quality cartooning; so few great books.

I don’t know whether I’d go so far as to say program fiction is a genre, Alex, but I’d definitely say it’s something comparable to “pulp fiction” with a certain flavor and culture and audience…although the individual identities of program writers and critics and art cartoonists and critics are often wonderful and vibrant and inspirational, they both tend to have a (very postmodern) subcultural identity (the Fiction Writer, the Alt-Cartoonist) rather than the “citizen of the world”-ness of a Hemingway or Faulkner or the incisive and broad social wisdom of an Austen or Wilde. Subcultural identity is safe in a way that perhaps authors should never be. I think that Batuman’s discussion of the professional mission of the Program — the role of Shame — is a lesson that fiction writers and critics should take to heart.

It’s obviously up to comics criticism whether to take it to heart as well, but transpose this passage:

“Shame also explains the fetish of ‘craft’: an ostensibly legitimising technique, designed to recast writing as a workmanlike, perhaps even working-class skill, as opposed to something every no-good dilettante already knows how to do. Shame explains the cult of persecutedness, a strategy designed to legitimise literary production as social advocacy, and make White People feel better (Stuff White People Like #21: ‘Writers’ Workshops’).”

Here’s a pass at recasting:

“Shame also explains the fetish of ‘craft’: an ostensibly legitimising technique, designed to recast [cartooning] as an [elite] skill, as opposed to something [done for hire by a pulp press]. Shame explains the cult of persecutedness, a strategy designed to legitimise comics production as high art, and make White People feel better (Stuff White People Like #21: ‘art comics’).”

The historical details are different, but the culture and values and, well, the psychologies of the Writing Program and of art comics — are they really that different?

What’s interesting about the Batuman article to me is that it displaces these questions of how much theoretical/critical perspective a book has to have or insight a creator has to have (or doesn’t need to have) onto the more socio-cultural question of the ways in which subcultures, no matter how supportive, no matter how dedicated to quality and craft, might actually interfere with “seeing.” That’s been a theme here before, no?

As often when arguing with Caro, I have to capitulate; the recasting is brilliant.

I’d argue that modernism wasn’t the last organic cross-disciplinary art-movement. I think that would be theory…and perhaps still is to some degree. In any case, I definitely think that the antidote to program fiction is not (not not NOT) Ira Glass, but Slavoj Zizek.

Also…I think perhaps the promise of comics, or one possibility of comics, which it can offer to the broader arts and the broader world, is maybe its betweenness, both in terms of form and of history. Partially as a result of that, comics can, and often do, arrive at that place where craft or perfection on a small scale is abandoned or absorbed into a more ambitious effort. That’s certainly the case for Moto Hagio, for example, who (as I’ve said) can’t really handle story or character at all, but ends up turning that to her advantage in many ways.

I think there’s also a strong desire (tied, I’d argue, to shame) to reify comics identity — to prove its worth by drawing boundaries rather than breaking them. The critical obsession with definitions is perhaps a case in point. So is the focus on lit comics, in its attachment to a more prestigious cultural form. So in some ways are the efforts at amalgamation which Domingos was talking about.

Caro, I clearly meant the former option you give me, that Robert and other critics don’t give Popeye or other comics of its kind enough credit for what they do, but I still believe that this is in part *because they approach them with a set of values, or a vantage point as you say, that blinkers them to those qualities (I really don’t like to assume anything on Robert’s part though – sorry Robert! – this is more a general point, and I really liked his reviews of Popeye on his own site regardless). Of course no approach is fundamentally wrong and there’s plenty in modernism for us to learn from. And I’m certainly not advocating any kind of “working class elitism” or what have you – merely suggesting ways to better the conversation as I see it.

As for that quote from Mouly, I just find it incredibly depressing, and your spin on it doesn’t cheer me up/ You make literature or art sound like puzzles to be solved, puzzles which don’t bear repeating. I don’t recognize the experience at all and remain skeptical that being aware of the tricks or innovations of earlier generations of artists is somehow essential to making good art. In some cases, critical and theoretical awareness is clearly a great thing for an author or artist, but as a general principle it sounds oppressive and dull to me.

And I really don’t buy the program thing. I agree with much of what Batuman is saying about contemporary literature, but am unsure to what extent the writing schools and workshops are to blame. But that’s another discussion and probably one where I’m on thin ice.

When it comes to comics, however, I don’t think it applies. You make it sound like contemporary comics is a wasteland plagued by anxiety and shame. I don’t recognize this *at all*: we’re in the midst of what is perhaps the most exciting era in comics since the early 20th century, the medium is more diverse in terms both of subject matter and idiom than ever before, and it seems things are only getting started. Sure, not every book out is a masterpiece, but there’s still an impressive amount of those going round for such as relatively small medium.

To me it’s simply one of the most vital art forms these years. Fetishizing craft was arguably an issue in comics a decade or two ago, and it remains an issue for some cartoonists, but I can’t see that it’s a problem for comics as such today. And sure, there’s a lot of negotiating what comics history means to the form as it’s developing now, and it’s not all equally pretty, but that’s only natural in that comics are exploding its traditional, rather narrow genre restrictions and idiomatic forms – which is a situation entirely different from what’s happening to the novel.

Where your comparison works better is with comics criticism, and to an extent academia – with the important difference that the ‘program’ is self-generated rather than institutional. But again, that’s only to be expected since there’s so comparatively little of it going round, but I definitely believe things are changing for the better.

Oh, and I dig Johnny Ryan’s stuff a lot too, Noah! Though why you hatin’ on This American Life?

Noah: “I definitely think that the antidote to program fiction is … Slavoj Zizek.”

We’re doomed.

Of course! That’s the beauty of it.