I’m blogging my way through all the stories in A Drunken Dream, the collection of Moto Hagio’s stories out from Fantagraphics. You can see all posts about this collection here.

_______________________________________

Moto Hagio’s “Hanshin: Half-God” is about Yudy and Yucy, conjoined twins. Yudy, who tells the story, is ugly, shrivelled, articulate, and competent; her twin sister, Yucy, is a beautiful, mute parasite, who sucks away both Yudy’s nutrients and the affection of parents, relatives, and passersby. Yudy has to help Yucy walk and bathe and perform even the simplest tasks; in return, the simple Yucy gives Yudy frequent fevers and bothers her while she tries to study genetics. Eventually, doctors decide that the twins will die if they are not separated; the only choice is to cut loose Yucy, who will die, allowing Yudy to live. Separated from her twin, Yudy grows into a normal young woman. The end.

Sort of. If that was the story, it would be a fairly straightforward, even banal feminist parable about casting off gender expectations in order to find your true self. Yucy, the delicate, helpless, beloved beauty, has to be destroyed before Yudy can grow up into a competent, independent woman. QED.

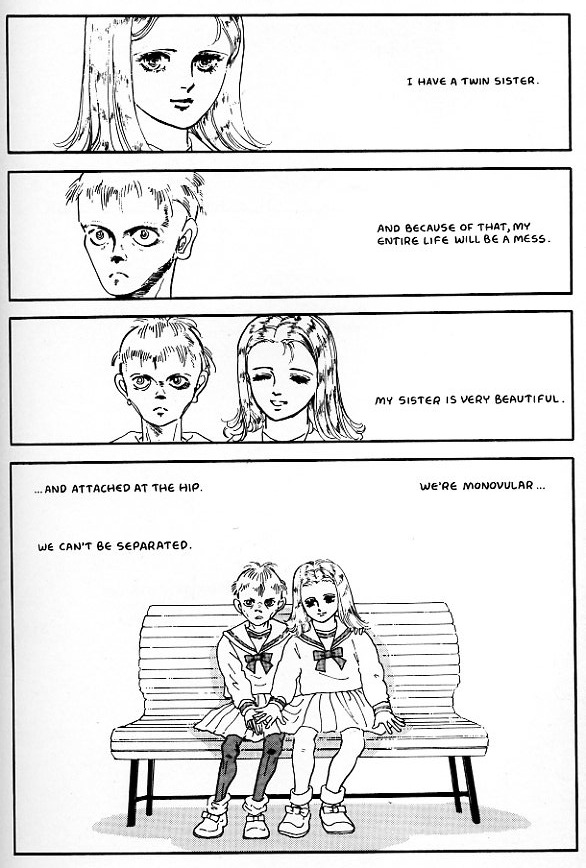

In this reading, Yudy and Yucy are different aspects of the same person…and there’s plenty of evidence for that in the art. For instance:

The first panel show Yucy off to the left against a blank background; then the second shows Yudy in the same position. In the third we see the two together…and only in the final panel on the page do we learn that they’re “attached at the hip.” The surprise reveal is, though, clearly rigged. If the two are attached, we shouldn’t be able to see them without each other. Particularly in the second panel, Yudy is placed so that we should see Yucy to her right — but all we see is blank space. The implication is that Yucy doesn’t exist except as metaphor…or perhaps, that Yudy doesn’t, since it’s Yucy we see first.

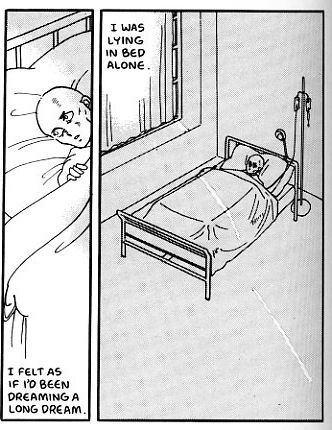

Again, just after the sisters have been separated, Hagio put in a tell.

“I felt as if I’d been dreaming a long dream.” The twin is just a fantasy; only when she is separated is Yudy living real life for the first time. The perfect girl she is supposed to be doesn’t exist.

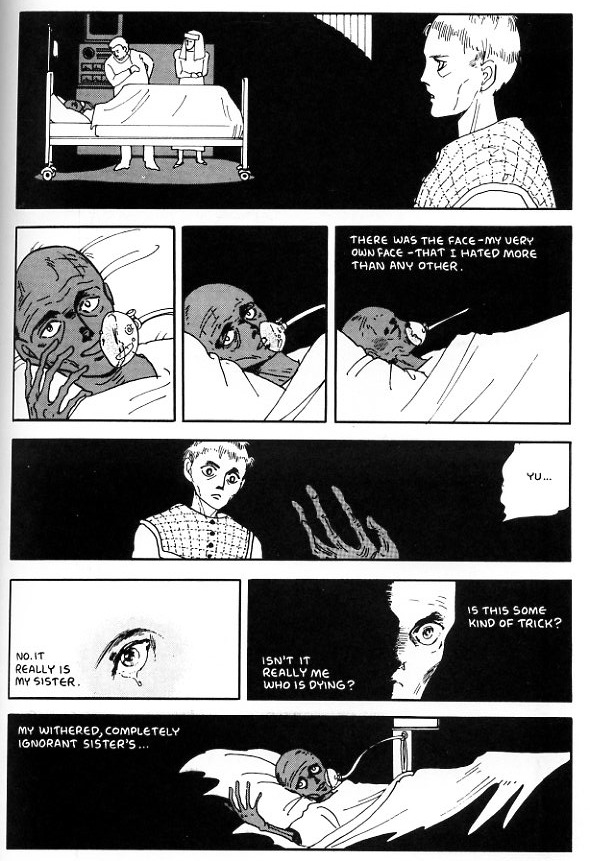

Except that she sort of does. Yucy doesn’t die immediately after being separated; instead she slowly wastes away. Yudy goes to visit her one last time, and is startled to see that her sister has turned into her own mirror image.

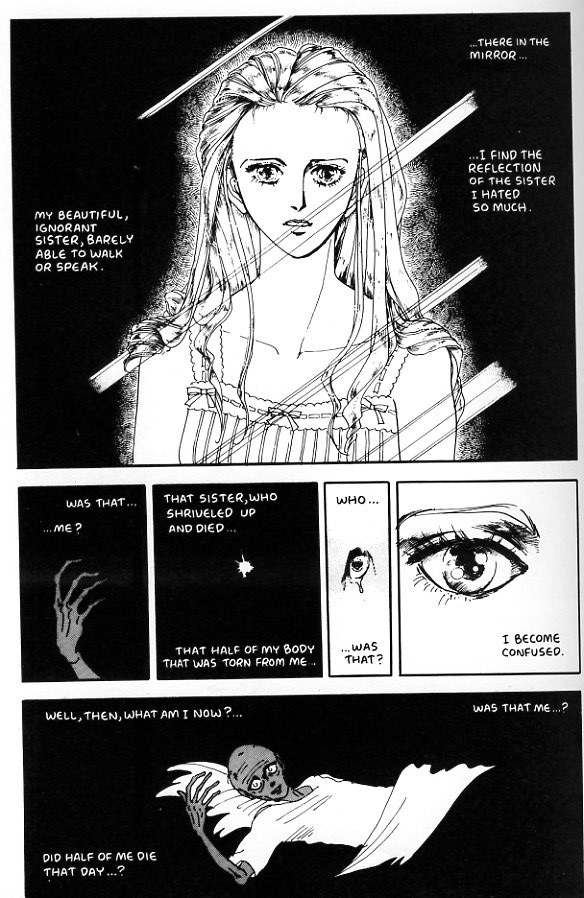

You could see this as still being about the escape from gender stereotypes — “Isn’t it really me who is dying? No it really is my sister.” Again, this could be a statement that the gender-normative self is not Yudy; that she has escaped other’s expectations. But the affect is off. Instead of joy or release, Yudy feels disorientation and grief. The self she has left behind is “really” a self; indeed, it now seems more like the real her than the her that has survived. As time goes on and she becomes healthier and healthier, Yudy begins to look like the sister who died, until finally she wonders which of them was killed:

The story is no longer about casting off an oppressive femininity. Instead, it’s about…what? Betraying the self perhaps…but how exactly? Has Yudy betrayed herself by turning into the femininity she thought she was rejecting? Or was the rejection of that femininity — which also encompasses childlike innocence — itself a betrayal? Or is it the loss of her pain which is a betrayal; leaving behind the helpless, shrivelled, wretched self to become a competent adult? If so, the bind seems double and unescapable; to grow up, one has to abandon one’s attractive weakness, but doing so is always a betrayal of that weakness. The child is not the adult, even moreso because the child is still there in your face. Or, perhaps, the conflict is not internal at all. Perhaps the bond that holds together Yudi and Yuci isn’t sisterhood or self, but love, and it’s the abandonment of that love for femininity which causes Yudi to both become more feminine…and to be haunted by the conviction that she has lost herself.

There isn’t any one “solution” to the story, of course. This is emphasized by the fact that there isn’t one Yudy, or even two, but many. In a recent post about doubles in comics, Caroline Small suggested that comics can do doubling in a way that is less “labored” than prose. I was skeptical about this — but Hagio’s story may have changed my mind. Because in “Hanshin,” the metaphorical uncertainty around Yudy and Yuci becomes an actual, concrete ambiguity. That is, when Yudy sees Yuci lying on the hospital bed, and wonders, “Is this me or is this my sister?”, the narrative insistence on ambiguous doubling actually obscures the concrete doubling — Hagio is, in this sequence, drawing the same person twice — or more accurately, six times.

Yudi and Yuci in Hanshin are just names, assigned as Hagio wishes to different iterations of the same body. In her confusion about who she is, Yudi is more, not less, aware of reality — she senses the arbitrariness of Hagio’s choices, the way that names and identities are linked, not as absolutes, but through arbitrary decisions.

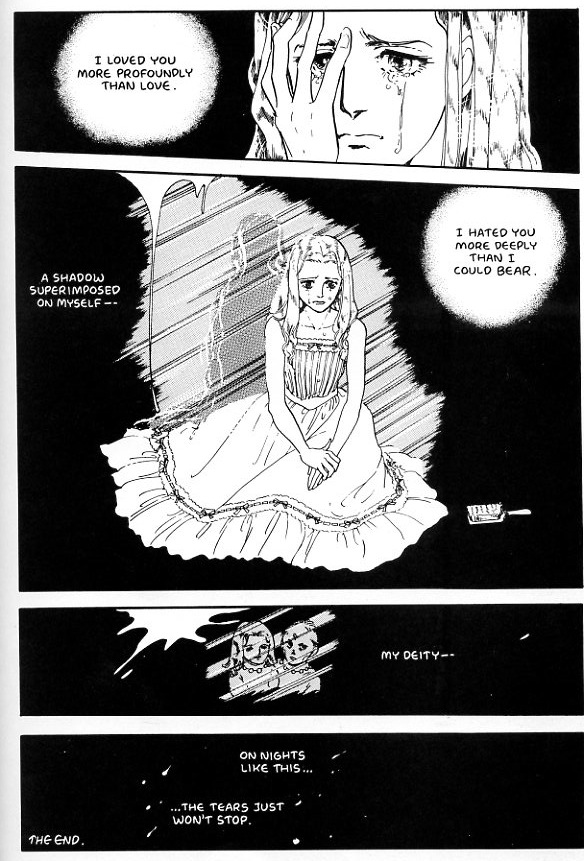

We “know” that is Yudi, but if Hagio changes the words, it could just as easily be Yuci who grew up. Which raises the question…who is talking here? Is that Yudi? Yuki? Or is it Hagio herself? “I loved you more profoundly than love. I hated you more deeply than I could bear. A shadow superimposed on myself….My deity —” Whose shadow? Whose deity? If one is drawn as two and two as one, who is doing the drawing? The same person who did the killing? Is the deity the one who is there or the one who is not, and how can you tell the difference? To create your soul is to split your soul; a god who has always already left half of herself behind.

I still can’t believe Moto Hagio and Keiko Takemiya were roommates. Have you read To Terra or Song of Wind and Trees?

Knowing Hagio’s backstory, I always thought this story was about pretending to be someone you aren’t to win love and approval… growing to reject this person… and then realizing that you are an incomplete person without her, that you have also thrown away a very real part of yourself.

But if you feel strongly enough about your assumed persona to believe that she is not you, she is another person entirely, there’s also the possibility that you may one day find an actual, external person who resembles your ideal. Then the reality and the ideal become all mixed up…

That the “real” person, who is shriveled from neglect and disuse at the beginning of the story, grows up to resemble the “fake” person, who is acknowledged to be a real part of the self, is a very mature conclusion, I think.

I started To Terra, but really didn’t like it very much, unfortunately (the art is lovely; the story not so much.)

I think your interpretation of Hanshin makes sense.

I have nothing much intelligent to say on this at the moment, but I wanted to thank you for paying attention to this story. I read it in scanlation some time ago, and have been fond of it since. This sort of thing makes me want to read tons and tons of Year 24 Group shoujo, but unfortunately, most of it isn’t available in English – as seems to often be the case with the most interesting manga I run into.

That there were comics artists grappling in various ways with gender, sexuality and identity issues while those American creators who weren’t part of the R. Crumb/Spain Rodriguez crowd were still concerning themselves with superheroes is reassuring and even vindicating.

That they were doing so in stories meant for girls meant that their young fans were in there questioning with them, or at the very least being exposed to gender, sexuality and identity nonconformity presented in a positive light. If only the Year 24 Group’s American colleagues had been doing the same, we might have been spared years of gender (and identity, and sexuality) stupidity in mainstream American genre comics.

That’s probably hyperbole, but yannowhatImean…

I enjoyed this post and the comments. Like Subdee, I also felt this story is about two parts of the self pitted against each other. Fake or real, public or private, the difference between your appearance and your private thoughts. I think it appeared in an old Comics Journal? This story really made me love Moto Hagio.

It appeared in TCJ #269.

Where it made this cynical old fandreck stifle a tear or two…

The story works better if you consider either sister, not as a metaphoric mirror of the other, but as an individual.

Then I think the story works as an enhanced expression of sibling rivalry.

I grew up with three brothers– I know plenty about love and hatred between sibs!

I think it’s meant to work on all those levels. The metaphor is deliberately left vague, I think, which is thematic for a story about the porousness of identity.

Identity is indeed a very fluid concept. I’m constantly surprised at how different–both in appearance and in behaviour–some celebrities are now compared to when they were younger. Sure, some of it may be a put on, but as people mentioned here, how long can you pretend before it actually becomes real?

In show business especially, I think shifting from one identity to another is a trait many in the business must learn to do in order to survive.

But as Hagio asks, I always wonder what the psychological and emotional damage is when they do that, and sometimes they do it not just once but several times in their lives.

Hanshin is indeed one of the most memorable of Hagio’s works and is justifiably seen as a high point for her

Oh, I liked To Terra – how much of a completely blatant wish-fulfillment fantasy it is – with the “sensitive” kids being a separate race who literally have special powers (but are physically crippled), and the normal world being literally run by computers who enforce conformity, and all of these emotionally unstable personalities literally escaping to live together on a spaceship. And their spaceship society is a utopia, not the messy disaster one might have expected, because the Mu have ~telepathy~ and are able to completely know and understand each other. They never even seriously disagree about anything! It’s, like, charming.

Like Moto Hagio, Keiko Takemiya is taking emotional truths and turning them into an actual, literal truths. But she’s a lot less subtle about it than Hagio. XD I dunno, I enjoyed it. I even liked the way that all of the space ships looked like they were cribbed from Star Wars. (To Terra was serialized from 1977 to 1980.)

There’s a lot of specific stuff about this manga I really like, too – like the co-opted Intelligentsia class vs. the zombie breeder class, or the Keith/Matsuka relationship, which has complex psychological underpinnings I think – but I’ll spare you. :p The story does become a bit too “generic sci fi” at the end. But the setup has so much pure id, and the plot is so epically conceived, that I don’t mind that too much.

Song of Wind and Trees is really melodramatic and is probably half the reason why modern BL is as dramatic as it is. (Glass Mask and Rose of Versailles are the other half.) But if you’re more into ambiguity and nuance, Moto Hagio is probably the way to go.

This is reminding me that I always meant to finish Rose of Versailles and Glass Mask. They’re so long, though…

Did you read song of wind and trees in Japanese? It hasn’t been translated, has it?

No, in English scanlation… I read the commercial translation for To Terra. Sorry, sometimes I forget what’s commercially available and what isn’t.

Subdee–you raise an aspect that has always interested me. The Year 24 group (no matter which members you assume that group includes), but particularly Hagio and Takemiya dealt with a number of similar themes and stories. In fact, Hagio and Takemiya’s work nearly all can be directly compared with each other. Takemiya’s Terra E (which I’m a massive fan of–I think it’s great, over the top fun) and Hagio’s They Were 11 were sci fi stories in similar settings, similar themes and from around the same time. But it shows their similar, yet vastly different approaches. Takemiya’s work is all in broad strokes, melodramatic and external, Hagio is the opposite–sure there’s some melodrama, but her work at its best is very subtle and internal. Similarly Takemiya’s Song of Wind and Trees can be directly seen as a very explicit (and MUCH longer) reworking of Hagio’s Heart of Thomas. Even a work like Takamiya’s underated, polysexual 1980s slice of life series, Spanish Harem, shows this up.

Both women would rank within my top 3 manga-kas ever, but I admit that Hagio slightly wins out, for me.

I wish the Vertical Takemiya works had done better–personally I found both a blast to read (in some ways I even prefered Andromeda Stories which doesn’t seem to have much love online–of course the story outline for that was done by sci fi novelist Ryu Mitsuse). I certainly hope this Fantagraphics volume does well enough to lead to more.

Ikeda is of course the queen of melodrama–I actually think that by modern manga standards (or even compared with Song of Wind and Trees) Rose of versailles is remarkably tight and even short. I’ve read it in the gorgeously translated French editions (there’s a great French large sized volume of her subsequent work, OniisamaE, which I like even more), and if you cut out the later, barely essential side stories, it comes to about 9 volumes, or some 1700 pages, which feels like a flash in the pan next to most manga.

But I feel the shoujo tradition of melodrama goes back further–I’m a huge fan of Mizuno Hideko and how with her work you can see a direct line from Tezuka to Hagio (I wasn’t surprised to read she was the top female inspiration to Hagio). Her 60s melodramas, particularly one of my fave mangas Fire! are perfect examples of the genesis of this. (If only someone would translate that…)

As for Hanshin–I’d actually never before even thought about the aspect of the healthier twin being more *feminine*. It’s amazing how such a brief work can be read on so many levels.

@Eric Henwood-Greer – I just saw your reply! Thank you very much for typing all that out!

I haven’t read They Were 11 or Heart of Thomas yet, but I plan to.

If Hagio and Takemiya are both in your top three, who’s the third person? Tezuka?

Andromedia Stories/To Terra are interesting because as scifi stories, they hew more closely to the Western tradition of humanity vs. evil computers, and less closely to the Japanese tradition of humanity + friendly robots (which an article I just read claims is an attitude which descends from Shinto animism: a religious tradition which doesn’t draw such a thick line between the animate and inanimate, and sometimes ascribes positive emotions to the inanimate).

Song of Wind and Trees, also, is heavily influenced by… I don’t really have the words to describe this, but the decadent French aristocratic novels of the 19th century? Or 1930s revivalists like Colette? It’s not just the European boarding school setting, but the whole vibe. Anyway, when I was reading this, I thought of the way that outsiders often adopt the works of other cultures as their own.

I’m not sure nine volumes is really short, for shoujo… the longer-than-a-single-volume shoujo titles I’m familiar with seem to come in two lengths, around 4 volumes and around 10 volumes. I can only think of a handful that are as long as the average 20+ volume Shounen Jump series: Hana Yori Dango, Hana-Kimi, Please Save My Earth, Banana Fish, Fruits Basket, Tokyo Crazy Paradise, NANA, Glass Mask, Ice Cold Demon’s Tale. (And satirical series like The Wallflower, which are more in a josei serialized romantic comedy vein.) But this could have more to do with what gets picked up for translation/scanslation than with the average length of shoujo series compared to other genres…

I’d never heard of Mizuno Hideko. Now I’ll have to read her, too! Old school shoujo all the way! Or as a friend of mine observed: “I should just make a rule that I will only read shoujo if it’s over fifteen years old and everyone has enormous sparkling eyes, because that seems to guarantee quality melodrama…In new shoujo, you’re generally supposed to root for a mild-mannered nice heroine to get the attention of some jerky dude who is mean to her but is sooo dreamy, but in old shoujo, you watched batshit crazy girls go to ridiculous lengths to FOLLOW THEIR DREAMS (or whatever).”

Hey, no worries–it’s a pleasure for me to discuss classic shoujo, or ramble on about it as the case may be, and you raised a lot of interesting points.

In regards to the length of shoujo works, it’s funny, my first though is always that they tend to be 15+ volumes, so a work like Versailles, to me seems short and manageable. However, it’s true that I can’t think of one shoujo manga work *before* Versailles (which ran ’72-’73) that was more than 4 or so volumes (Hideko’s Fire!, just to mention my fave 60s title again, was seen as positively epic at 4 tankoubons). Maybe something like Tezuka’s Princess Knight, but that wasn’t one continuous story and had several incarnations already.

However, off the top of my head I can think of many longer shoujo titles. Besides the ones that you named, there’s Ikeda’s other classic 70s epic (this time about the Russian Revolution) Orpheus’ Window, which is a little over twice the length of Versailles. Takemiya’s Song of Wind and Trees of course as well as her 90s epic, Tenma, Hagio’s A Cruel God Reigns (her other works tended to be under 10 volumes), 70s classics Swan, From Eroica with Love, Aim for the Ace!, Arabesque, licensed titles like KareKano, Moon Child, X, Basara, Cipher, Sailor Moon, Fushigi Yuugi, Ceres, etc etc. I actually think the modern standard for a successful shoujo sereialized story, is about 15 volumes.

That’s a really interesting point about Takemiya’s sci fi and the more western viewpoint (although Andromeda Stories does have the C3PO/R2D2-esque helpful robots).

As for the early Takemiya and Hagio boys love stories and their influences–I think the influences you named are correct–also there was the work of Cocteau (Hagio was such a fan that in 1979 she did a great adaptation of Les Enfants Terribles) and, very directly (as mentioned in the Hagio interview), the French film Les Amities Particulieres from the early 60s, which I believe Takemiya took Hagio to see. It’s easy to find online, and while the romance in the French relgious school between the older boy and the younger one is never consumated, you see explicitly all the prototypes right there.

It’s very hard to find much about Mizuno Hideko in English, but I think you’d find her work fascinating. In that interview Hagio mentions her influence a bit, and like I said she’s such a clear brideg between Tezuka and the Year 24 Group’s work, it’s amazing. She started as an assistant to Tezuka and even if you compare her work when she was most active (late 50s to early 70s) you see a rapid progression from rather bizarre simplistic stories of poor little girls longing for a pair of shoes, to epics like Fire! (one of the first shoujo titles to win a major manga award, to feature a male protagonist, to deal with drugs and more importantly have the first sex scene, etc). I think even in Japan her work can be hard to find, though a bunch of it has recently been reprinted which is how a friend of mine there managed to surprise me with copies of Fire! (a title I had been searching for for about ten years–probably since I read about it in Manga! Manga!). This is the best, and one of the only, bits of info (with some examples from several of her major works–as well as plot synopsises that make her work sound even more over the top than they are) http://www.callenreese.com/mizuno.html

And BTW I completely agree with your friend’s shoujo philosophy :P

Thank you very much for your second long and thoughtful reply!

I see what you mean about series length. I didn’t think to include anything that came out before (say) 1990 – and some of those series are still running! I also think my friends and I tend to have shorter attention spans, and to prefer series that have a beginning, middle, and end, so something like say X/1999 or Tsubasa is out.

It still feels to me like 10 volumes is a respectable length for a 90s-present shoujo series, though – especially one built around romantic tension, you just can’t draw that out forever. (Unless you write a gag series.)

I forgot about the helpful robots in Andromeda Stories… as if the spaceships in To Terra weren’t enough of a tip-off that Takemiya was a really big Star Wars fan!

Now that I’m reading about Mizuno Hideko, I see that she also used Western settings and characters, so maybe that’s just were shoujo came from… girls’ missionary schools and so on… also, why is everyone blonde…

Fire is set in Ohio/Detroit! Rock on!

I am going to watch Les Amities Particulieres now.

XD

Noah, you’ve really captured what makes this story so powerful.

Hello, please, could you tell me where I would find more about Tezuka´s influence on Mizuno Hideko and Nijuuyonengumi?