I’m blogging my way through Fantagraphics’ Moto Hagio collection, “A Drunken Dream.” You can read the whole series of posts here.

_________________________________

Hanshin: Half-God and A Drunken Dream were both more plot hole than story; odd broken fairy tales with glimpses of trauma breaking through the prevailing aphasia. They’re unique, bizarre, and lovely.

“Angel Mimic” is, alas, much better constructed. There’s foreshadowing, thematic development, a final shock reveal — in short, all the elements of a traditional plot. As for what that plot is… Joe McCulloch over at Comics Comics has a good summary.

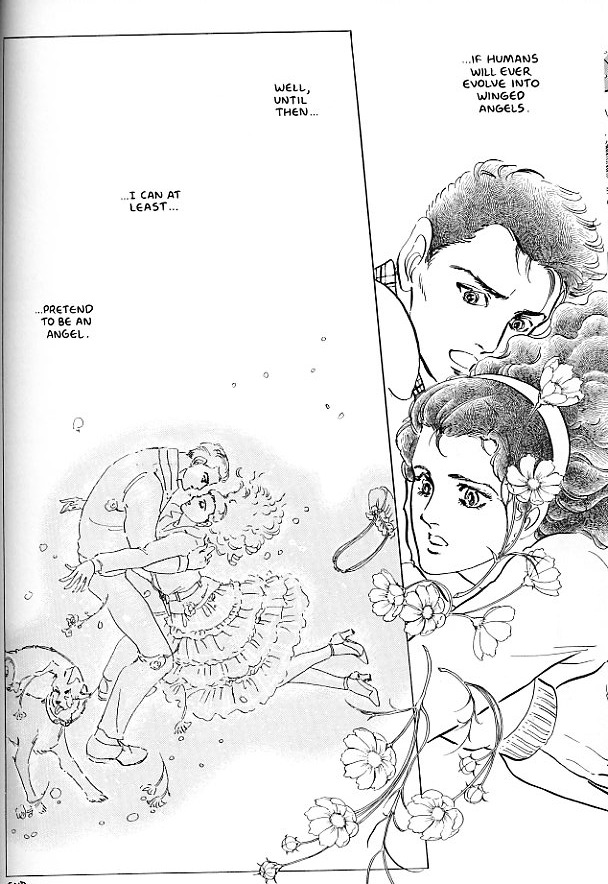

while a double-barreled blast of soap opera sees a suicidal girl hauled off death’s doorstep by a rough but handsome man who *gasp* turns out to be her new biology professor, resulting in detailed, evolution-themed educational segments (not unlike the learning bits in Golgo 13 or a Kazuo Koike manga) inevitably lashed to Our Heroine’s Dark Secret. “I wonder if humans will evolve into angels?” she muses, probably gauging the reader’s appetite for comics of this tone.

Joe’s a kinder man than I, so he doesn’t quite come out and say it, but — yeah, this is godawful. In her better stories, the fact that Hagio’s characters never for a second seem real gives her world an eerie air of unreality, like they’re pasteboard props erected to conceal an abyss. Here, though, more of the cracks are filled in, and Tsugiko ends up seeming less like a mask concealing wells of emotion and more like a hollow doll being pushed by rote towards the inevitable epiphany. There’s initial tension with the man who saves her — he wanders back into her life — they are thrown together by circumstance — they happen to meet her ex — they separate — they come back together — the secret is revealed — happy ending.

That secret (and hey, I’m going to spoil this crappy story now, so be alerted)….

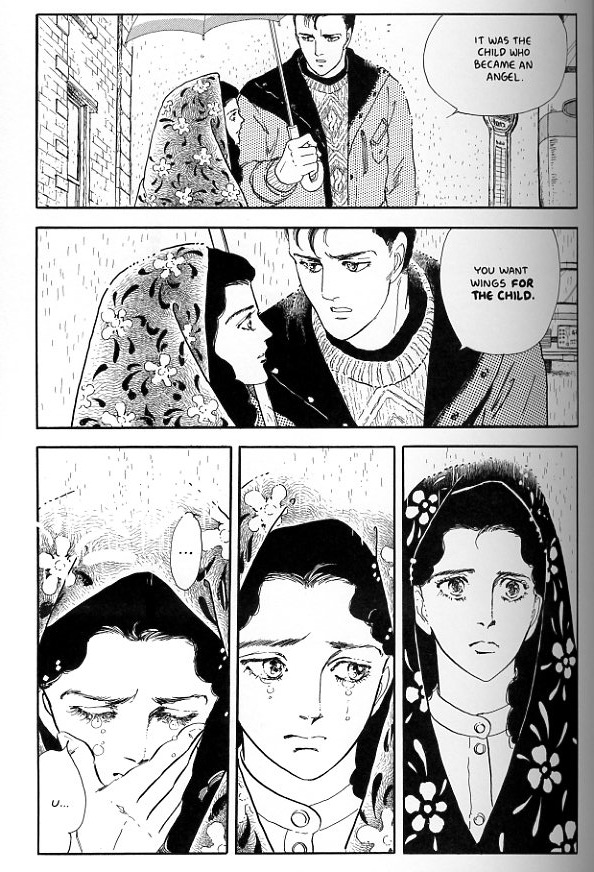

is that Tsugiko has had an abortion. Her reiterated wish that humans could evolve into angels with wings is, as her biology professor/lover keenly observes, actually a displaced grief for her baby, who she hopes has gone to heaven.

It’s hard not to be moved by Tsugiko’s look of shock and grief, the eyes delicately and liquidly rendered in the oval face as the background blurs out. The revelation, and Tsugiko’s reaction to it, is supposed to show us that she has depths. Unfortunately, though, it shows us the opposite. Her one (endlessly repeated, hopelessly trite, but still) bit of fancy, the one piece of furniture in her mental life, is shown not to be in her mental life at all, but in her womb. The doll is opened up, and what’s inside is just some clichéd tragedy and a maternal instinct. No wonder she needs a biology professor to understand her; all she is is her biology. He helpfully points this out, and in gratitude she throws herself into his arms, pretending to be an angel which, as we’ve just been told, means that she pretends to be his child.

The point isn’t that women shouldn’t feel grief for an aborted child, or that such grief isn’t a valid subject for a story. But if you’re going to tell that woman’s story, you need to tell her particular story, and Hagio just isn’t up to it. She’s interested in trauma, not people. In “Hanshin” and “Drunken Dream,” this worked out, because the story was sufficiently open that the trauma was nonspecific; it was the universe’s, or Hagio’s, the metaphor allowing space for poetry. Here, though, the trauma is defined, and that definition, sans actual character development, results in banality. Tsugiko is nothing but the pain of her abortion, and then, when her boyfriend takes away that pain, she’s just nothing. The failed suicide of the opening, the transformation into an angelic nonentity, is at the end not reversed but fulfilled. Happiness is escaping from the complicated choices of adulthood into the oblivion-bearing arms of some wiser father.

In her best writing, Hagio’s ambivalent self-hatred comes across as a complicated yearning/repulsion around both identity and gender. Here, though, that self-hatred actually reads as something uncomfortably close to misogyny; a desire to annihilate women and grant them the peace, if not of the grave, then at least of enforced and eternal childhood.

I’d be remiss, though, if I didn’t point out that not everything in this story is clichéd romantic melodrama.

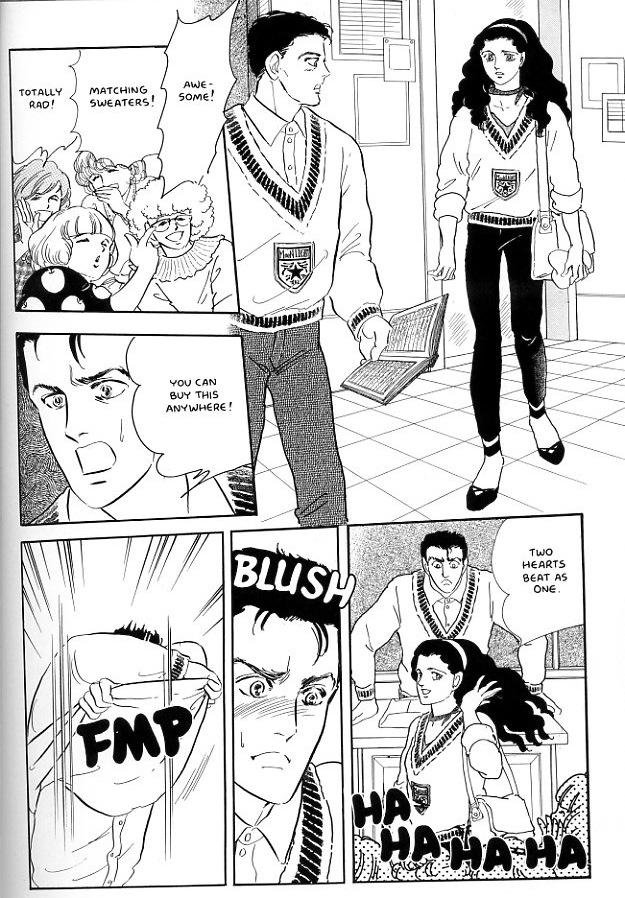

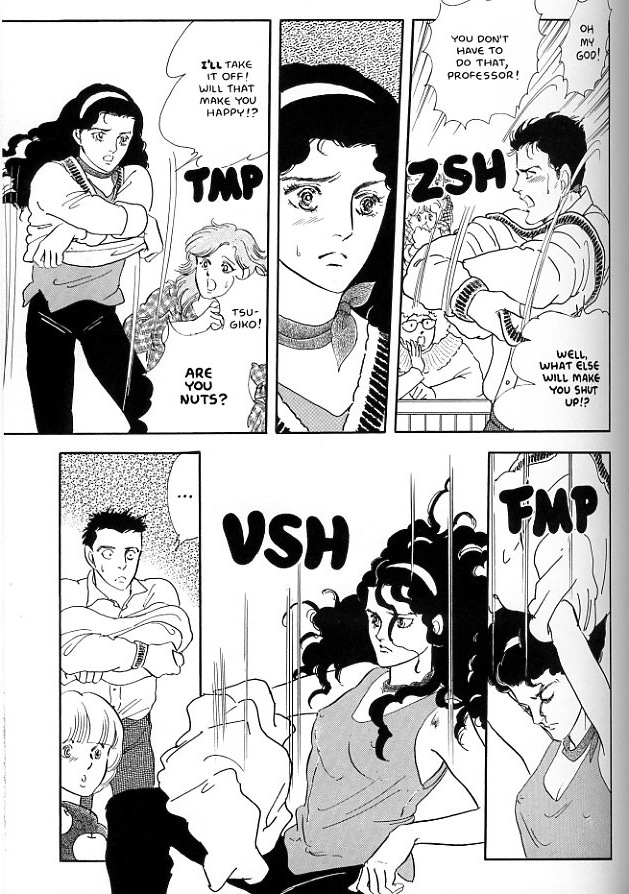

Some of it is clichéd romantic comedy. In this sequence, biology-professor-guy (named Shiroh) is teaching class when Tsugiko walks in late. It turns out they’re wearing matching sweaters, which sets the class to tittering. Tsugiko is amused, and even throws out a bon mot (“Two hearts beat as one!”) This isn’t Elizabeth Bennet, obviously, but it does demonstrate a rudimentary wit and a flirtatious self-deprecation which makes it seem for a moment like she’s maybe got a brain in there somewhere. Shiroh, anyway, is totally freaked out by this evidence of synaptic activity, and rather desperately pulls his sweater off. Tsugiko, though, ain’t going to be outdone; partly out of hurt feelings, partly out of pique, and maybe partly as courting behavior, she strips off her sweater. While teach has a button-down shirt under his outerwear, Tsugiko is wearing only an undershirt — apparently without a bra. Her nipples are clearly visible — and the act of pulling the shirt over her head has also frizzed her hair out. Even her body language is more aggressive; her legs are spread apart and so are her arms. She looks, in short, red hot, a fact lost neither on her teacher nor on her classmates (trust Hagio not to forget the homoerotic subtext.)

For these two pages, at least, Tsugiko is allowed to be something other than an angel-in-waiting. Specifically, she gets to be the spunky heroine in a romantic comedy. And, as we all know, spunky heroine=sexual aggressiveness=fan service for the nerdy guy. So, um…yay?

I suppose if I have to choose I’d rather have the spunky fan servette than the weepy dish mop. But that’s just personal preference; I don’t know that I can make a good aesthetic case for one over the other. Either way, this story really crap — mediocre and rote even by the standards of not-necessarily-fantastic-romance-fiction, like Georgette Heyer or Twilight or even — God help me — a really pernicious piece of dreck like Yes Man.

________________

So…what to make of Hagio at this point? I’ve read seven stories, of which 5 have been quite bad, and two have been masterful. I’m feeling like I’m getting whiplash — though, at the same time, there is common ground in all the work here.

That common ground is genre. Hagio is a lot more like, say, Jack Kirby, or Alan Moore, or Neil Gaiman than she is like Lynda Barry or Alison Bechdel. Most of these stories don’t take a stand as self-conscious art for art’s sake. Even “Hanshin”, the most idiosyncratic effort so far, is drenched in sentimentality and obsessed with prettiness. Indeed, you could perhaps read Hanshin as being about genre; the second self standing in for the shojo/romance genre itself, a twin that Hagio tries to abandon only to end up more perfectly embodying it.

In a controversial review, Chris Mautner argued that Drunken Dream was too girly to attract the art comics kids. I suspect he’s in part correct — but I also wonder if Hagio’s a hard sell in that neck of the woods because she really isn’t art comics. If, say, Steve Ditko had never been seen on these shores, and suddenly a book of his work was translated, would lit comics folks see it as especially relevant?

In any case, “Iguana Girl,” the next story in the volume, is supposed to be one of Hagio’s best, and it also looks like the one that may most closely approximate an art comics sensibility. We’ll see how that goes….

“Here, though, the trauma is defined, and that definition, sans actual character development, results in banality.”

I think this is the hub of the problem. The short story form as practiced by Hagio simply doesn’t suit this kind of romantic fiction. If anything, “Angle Mimic is not “romantic” enough, something which I find absolutely essential in this kind of straightforward genre tale. It has an absolutely deadening effect on the emotions. Asian film and TV is littered with much better product by comparison.

Oops, that would be “nub” not “hub”.

That’s interesting. I hadn’t considered the possibility that it might be the length which is the problem. I can see that though; she either needs more holes in the narrative or more space to stretch out the character development (as in Nana, for example.)

I don’t think Hagio is as gifted in short stories as she is in long-form works; her best work tends to be grand, sweeping, operatic melodrama, which is hard to carry off in one 32-pages-or-less installment.

It’s really too bad then that all we have in English is the short stories (barring scanlation, of course.)

I think it would be interesting to see these and other Hagio works situated in the historical development of yaoi and shoujo manga itself, given that she was a major figure in the Year 24 Group of early genre developers. How much of this badness was Moto Hagio being genuinely bad, and how much of it was Moto Hagio and her colleagues still figuring things out, and doing so on tight deadlines?

Also, I’d like to point out that I’ve -never- heard of an artist being “too manly” for the art comics crowd, which seems to be really enjoying the discovery and translation/publishing of works from Garo – a magazine drenched, not only in artistic merit, but in near-constant misogyny.

The fact is that women cartoonists don’t have the opportunity to look back to our American foremothers, because there more or less weren’t any; even that feminist icon/bondage model Wonder Woman was the creation of a guy, and her having being created by a straight guy is evident in every awesome-but-problematic element of her existence. Even the comics targeted at women here in America were all made by men; if we must find our foremothers halfway across the world, then we will. Is it so bad that said ancestors were/are purveyors of beautifully (if sometimes clumsily) executed goop for young girls? If we were to criticize American genre artists at comparable levels of genre development through a similar lens, looking at the work as musclebound conflict porn for young boys, would they really come out much better?

I’m not saying that Moto Hagio is the Greatest Ever or anything, but I think she is great within the circumstances in which her work developed, and I’m betting that careful historical research would vindicate that.

This is the point at which I admit that I haven’t read the collection itself – I read some of the stories in scanlation form before the book was released. I just find it funny that Hagio is being held up as “too girly” in a male-dominated field. Am I allowed to sniff at Jack Kirby for being “too masculine” now, completely ignoring the market for which he was creating?

Also, Noah, have you read/reviewed Hagio’s The Heart of Thomas?

Hey Anja. I actually make fun of the male genre tropes of American comics with some regularity. Here for example. And, just in general, I’m not a huge Kirby fan. He’s fine; I enjoy his work, but he’s not a personal favorite. I like Hanshin better than anything I’ve read by him, I think.

I think it would be interesting to see a substantial review from someone with more knowledge of the Japanese context than I have. (If anyone wants to write such a thing, let me know and I’ll be happy to print it!) However, even with context…if it’s not very good, it’s not very good. I don’t think it’s especially helpful to either Hagio or her readers to grade on a curve. Some of the stories in the book are (in my opinion) really first rate; others (again, in my opinion) not so much. There’s not any amount of historical research you could do that would make me think that this story was anything but a dud. Context is an explanation; it’s not an excuse.

That of course doesn’t mean that folks can’t be inspired by her work. But I think even if you are inspired, it’s worth thinking through what you might want to take away from her and what you might not.

Sort of by the by…Marston, the creator of WW — calling him straight is technically correct, but a little misleading. As you note, he was really into S&M, and his main romantic relationship in his adult life was with a lesbian couple. I think his sexuality definitely qualifies as queer in many contexts.

“There’s not any amount of historical research you could do that would make me think that this story was anything but a dud. Context is an explanation; it’s not an excuse.”

Well, part of the purpose of this book is to be a historical retrospective, and so one of the big things it is lacking (aside from “not making horrible glaring errors in image attribution” – seriously, did no-one proofread the back matter?) is the context of the individual stories, which the included interview doesn’t really provide. I don’t think this story is “a dud”; in 1984 abortion was a much more taboo topic and dealing explicitly with it was a much bigger deal than it is now, when it’s been a standard angst-point in all kinds of “gritty” shoujo and josei for decades. That’s the problem with historical retrospectives; stuff that was important because it was new isn’t new anymore, and thus loses its effect.

It doesn’t deal with the issue particularly well, though, is the problem. It’s used as a melodramatic shocker, and the solution is to find a wise older man to take care of you; not especially thoughtful, even if it was unusual to speak about the issue in Japan at that time.

Just got my copy in the mail this week…

I’m really enjoying it so far, but I was really surprised by the lack of context as well (althought I liked the interview, and it makes me want to read Heart of Thomas). I mean, how hard would it have been to include the actual publication date of all the stories on the title page, and maybe what magazine it appeared in? There could even be some page that addressed what the magazine typically printed, etc. Many otherwise excellent manga releases seem to fall down on this point, failing to provide context.

I still have this reaction to Moto Hagio which is probably injust and subjective and sexist… with all her tremendous skill, she still gives off this aura of “pwease wuv me, oh pwease don’t hurt me…”

It just feels manipulative, but then, is it illegitimate for art to be manipulative? In a very different vein, Jack Kirby’s art is certainly manipulative. As is Bellini’s or Rossini’s or Victor Hugo’s in their various domains…

I think the basic problem with her art is that it excludes ambiguity, plural interpretation. What you see is what you get.

And if what you see falls short, there are no redeeming factors apart from pure craft.

I think saying it excludes ambiguity is really wrong. Her best stories are almost all ambiguity and you really have to fill in the gaps to even figure out what the narrative is, much less what it means.

They’re definitely emotionally fraught…but as you say, that’s the case with a lot of art.

Noah – thanks for the thorough response! I was not aware that Marston was polyamorous. I wonder if he engaged in kink in real life, and not just in the bedroom…?

You’re right, of course, that a sexuality such as his can be considered queer. Straight queers are awesome (and make great allies for us bendy queers!), and Marston was one – I was just pointing out that he imbued Wonder Woman with his woman-lovin’ male gaze, like other American comics creators.

I’ve tried to like Kirby, I swear I have! I appreciate him now as a designer and colorist, which is more than could be said of me before. I often feel, though, that the superhero crowd are so busy waving their masculinity around (and ignoring their own queerness in the process – nice Eve Sedgwick reference!) that they blind themselves to any fantasy that isn’t “theirs.” It’s like they run towards heteronormativity so fast they end up running past it, straight towards the pink kryptonite.

And, um, sorry about kind of misreading your intent in panning these stories (which I should read the rest of! D’oh). I forget to get out of my defensive kill-the-kyriarchy crouch sometimes.

Context is difficult – I find myself appreciating an artist for doing what they did under the circumstances, or for being better than what came before, without really enjoying the work that much. Conversely, though, a bit of context can be all I need to really enjoy a work – I don’t take the same pair of eyes to watching Metropolis as I do to watching Avatar (and judging it to be vastly inferior, of course – not that I’ve ever seen Avatar. Heh…). I think that comics fans of all stripes have to keep context in mind quite a lot when viewing older work, and in fact end up leaning on it overmuch at times in order to ignore glaring flaws in the beloved work. Then again, classic comics artists in general can be hard to love at times – I attended a panel discussion with Dan Clowes at APE this year, and he said that the comics history he dialogues with in his work is almost an imagined history, an emotionally-driven mental pastiche of what these great artists -should- have been able to do, not what they -were- able to do.

Alex Buchet – The best Hagio work that I’ve read is plenty ambiguous. In fact, it risks at times doing a full-on, head-first Woman In The Dunes and -glorying- in ambiguity. I’ve never seen Moto Hagio as a WYSIWYG creator.

As for emotional “manipulation,” plenty of great art is heavily emotional, as you say – are you indicating that you think she does it unsubtly or poorly, or are you saying that you just don’t like emotion in art? If it’s the latter – and I mean this in the most respectful way possible – why are you spending your time with Moto Hagio, instead of, say, Sol LeWitt?

—

My transformative Hagio-reading experience was a scanlation of The Heart of Thomas. I still consider it to be the best Hagio work I’ve read. I’d really like to get my paws on A Cruel God Reigns, which is supposed to be the “grown-up” remake of Thomas, but I haven’t been able to find a translation.

Noah – Perhaps some Japanese-language scholarship on Hagio and the rest of the Year 24 Group can be translated and printed by TCJ? I’m sure there’s some good stuff out there, given how important the Year 24 Group was in the development of shoujo and shonen-ai, and I don’t doubt that the scholars of that fine Pacific island would appreciate some royalties…

Hey Anja. I don’t actually have any say in what Tcj does; HU is kind of our own thing. I would looooove to print japanese language scholarship on the year 24 group — but finding/organizing that sort of thing is pretty difficult, especially given the translation barrier, alas.

Also….”kink in real life and not just in the bedroom” — I’m probably demonstrating horrible naivete here, but I have no idea what you mean. He lived openly with two women at the same time and had children with both of them…does that count?

Noah said it already, but to say that Hagio’s work excludes ambiguity confounds me. I have to admit I have a higher threshold (and even kinda love) for the things that Noah and others have complained about in some of these stories so far, including this one. (But if somebody does consider the story bad, it can’t be blamed on Hagio’s inexperience or lack of contro as someone asked above–not in this case anyway as Angel Mimic stems from 1984, by which time Hagio was firmly established).

I do agree that Hagio’s short story work and long form work are vastly different, and play to quite different strengths (and weaknesses?). Her best short fiction is, I think, strong because of the aforementioned ambiguity–out of her short work that I’ve read, I would have definetely included a mid 80s piece that has been scanlated, Slow Down. The characters tend to be basic archetypes, and the stories there to express an often vague idea or theme. Whereas in her longer works (Thomas and its prequel, They Were 11 and its sequel, the underated Mesh, Marginal, and to me her melodramatic masterpiece, A Cruel God Reigns would be my picks as the best–Poe Clan somewhat falls between the two, being interconnected short stories written sporadically over a period of time), the pieces genuinely become character based, in the best sense of the term.

I wonder if it was a mistake to try to introduce Hagio to the Fantagraphics comics crowd via her short works (I suspect the next Hagio piece they tackle–and we’ve been all but promised there will at least be one more–will be one of her shorter, long works like Otherworld Barbara or Thomas). While I rather delight in it, they do show her at her “girliest” (for lack of a better term).

I think to many this will simply sound like an excuse, but I appreciate her short work best usually some time after I first read it. I find a lot of the ideas, or images (both on the page and in my head) come back to me with increased resonance. But I freely aknowledge they simply aren’t for a lot of people (on the other hand, someone who may not read a lot of modern manga, or Fantagraphics other titles, might find they6 appeal in a way other titles haven’t).

I do agree that it’s kinda surprising about what details weren’t included in this edition. At the least, I think they should have given the actual original dates and not just the copyright dates. I’ve read at least a dozen blogs that think the opening, extremely early stories were from 1977, for example (and there’s a massive difference in what was being done in shoujo manga in 1977, compared to 1970).

Still, I have to say I really don’t see her work as any more manipulative (I won’t even touch the “pwease wub me” comment ;) ) then anything by a modern manga-ka, or someone like Moore for that matter.

And just to ramble on a tiny bit more, I have to say that despite shaking my head (and admittedly laughing out loud) at some of these negative reviews–I’ve actually really enjoyed reading them, as well as the comments, and just trying to get a different perspective on it all. I’ve gotten a lot more out of them than I have from any of the positive reviews I’ve read so far (how’s that for being a kiss ass?).

Erg, “Kink in real life and not just in the bedroom” was a mistype. I meant “kinky in real life and not just on the printed page.”

Glad it’s not too irritating, Eric! It’s interesting to hear that Hagio’s longer works are so different. I do hope Fanta translates one of them next (or shortly).

Ha, no I wouldn’t stick around if I didn’t find the discussion fascinating.

My dream would be for them to next tackle Hagio’s A Cruel God Reigns. However, it might be too unwieldy for a new manga publisher (at over 3000 pages, originally collected in 17 volumes).

More likely knowing Matt Thorn’s love, and my second choice anyway, would be The Heart of Thomas. In fact, the short story that’s most inexplicably missing from A Drunken Dream is her groundbreaking 1971 title, November Gymnasium which Hagio has admitted was a sort of test for Thomas. The *only* logical reason I can think for it not being included is they were saving it as a bonus for a deluxe Thomas volume, but perhaps that’s wishful thinking. (Even more wishful thinking would be if they included in the volume, the short, later semi-prequel to Thomas, as well).

Otherwise, I suspect the next Hagio would be the fairly short, but no less welcome, Otherworld Barbara…

Finally I get it!

You have been expecting these stories to be “art comics”!

No wonder you have been so wildly disappointed.

Hagio has never been nor ever pretended to be an “art comics” creator. She has been a creator of thoughtful, well-crafted entertainment for her entire 40-year career.

What you’ve been doing is akin to using Fellini as a measuring stick for Frank Capra. Square peg, round hole.