I’m blogging my way through Fantagraphics’ Moto Hagio collection, “A Drunken Dream.” You can read the whole series of posts here.

_________________________________

In reviews of Drunken Dream, “Iguana Girl” is generally pointed out as the highlight of the collection along with Hanshin: Half-God. The two stories are similar in a lot of ways; both involve sisters, one beautiful, dumb, and beloved, the other (our heroine) homely, smart, and despised. And both are engaged with ideas about self-image, femininity, gender, and identity.

Hanshin, as I said in my review, is more a poem than a story. It raises questions deliberately to leave them unanswered — the narrator’s self is ultimately her lack of self. The identity she finds is that she does not know who she is: herself, her congenital twin, or the space left between her and her sister when they are separated.

“Iguana Girl”, while using a more arresting gimmick than “Hanshin,” ends up being a more conventional (and to my mind a less interesting) story. The plot focuses on Rika, a child whose mother sees her as an iguana from the moment of her birth. Rika’s perceived ugliness makes her mother hate her; she much prefers her second daughter, the lovely (and rather dumb) Mami. Rika sees herself as an Iguana too, though everyone else sees her as a beautiful girl (and eventually as a beautiful young woman).

The problem here is the same one that dogs many of Hagio’s stories — a lack of characterization resulting in glibness.

Specifically, while Rika is somewhat fleshed out, her mother remains a cipher. All we really find out about her is that she doesn’t like her daughter. Hagio robs her of her humanity much more effectively than the mother robs her daughter of the same. And since the mother is not really believable, the mother-daughter relationship which ties the story together falls apart as well. The emotion at the heart of the story rings false — which, for an artist as reliant on emotion as Hagio, is a serious problem.

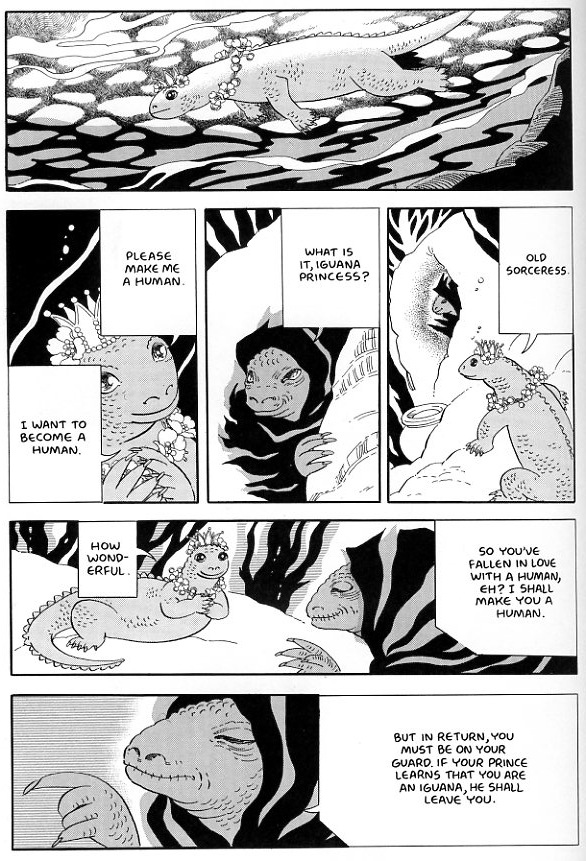

Hagio actually seems aware that this is a problem, and she attempts to rectify it at the conclusion of the tale through a dream/vision in which Rika imagines her mother as an iguana. The mother/iguana asks a sorceress to make her human in order to marry a man.

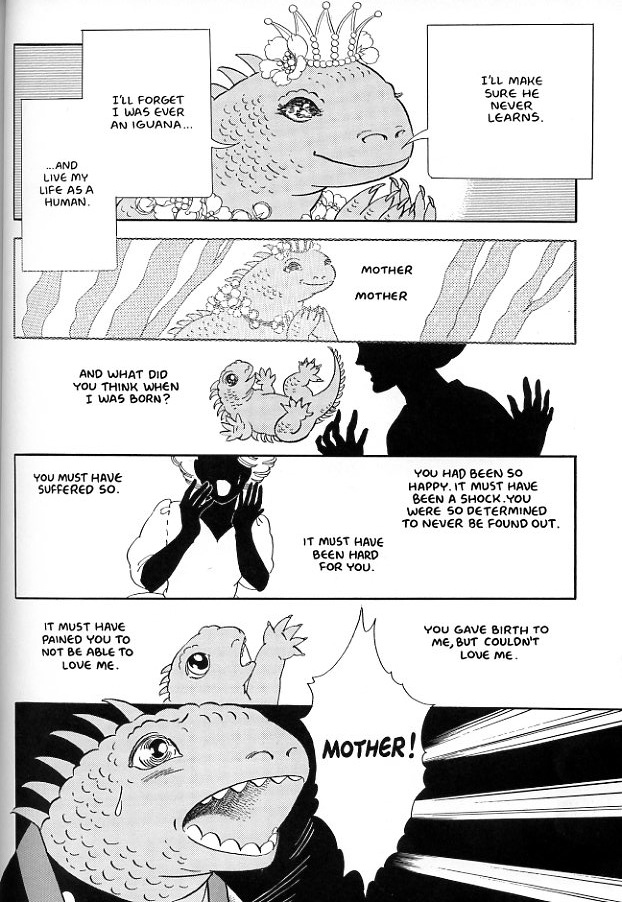

Rika then imagines the pain her mother iguana must have felt at giving birth to an iguana rather than a human. Realizing that her mother is an iguana contradictorily humanizes the older woman, and Rika is able to forgive her, love her, and therefore love herself and her own (human appearing) infant daughter.

Or I think that’s the theory, anyway. Unfortunately, as a storytelling mechanism the vision of iguanas can’t bear the weight that Hagio puts on it. The mystical backstory is no substitute for some sense of who Rika’s mother is as a person. If she’s going to be real and sympathetic to the reader, we need to see her behaving like a real sympathetic person. She can’t have been horrible to Rika all the time surely. And even if she was…we don’t even get any moments of genuine affection (rather than aggressive sickly petting) with her other daughter. Nor do we see any moments that explain what she meant to her husband; we only see his grief, disconnected from its context.

Hagio seems, in other words, determined to make us see Rika’s mother as soulless — and then tries to make up for it in the end by turning her into a faery, or a fiction. It’s not polite to psychoanalyze an author, obviously — but the implications are hard to ignore. Under cover of forgiving the mother, Hagio consumes her, turning her into her own creature in a symbolic mirroring of the way that the mother turned the daughter into her own monster. “Iguana Girl” presents itself as a story of imaginative forgiveness, but it feels much more like an imaginative revenge. The tension between what the story wants to do and what it actually does comes across less as irony than as duplicity; the happy ending seems meant to conceal the bitterness and fundamental unfairness of the narrative. Hagio builds the case against the mother and then indulges in the luxurious pleasure of righteous absolution without doing any of the difficult work of understanding. The result is a creeping duplicity which mars the story throughout, but especially at its ending.

___________________________

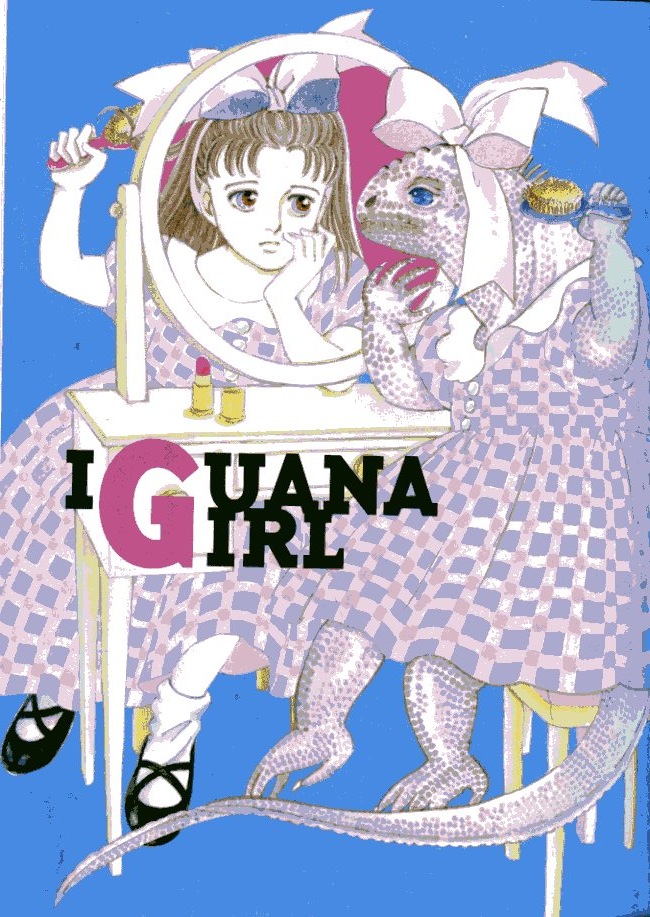

So that’s what’s not to like. On the plus side, though, there is Hagio’s delightful cartoon Iguana version of Rika. Hagio’s drawings for most of her stories are full-bore girly melodrama, with flowing tresses and flowers and big teary heartfelt eyes just beginning to brim over.

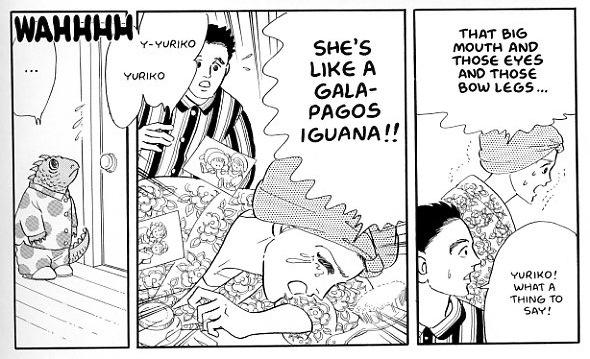

Not that there’s anything wrong with that, but it is nice to see her do something else, especially since her kawaii anthropomorphic animal thing is so energetically delightful. Indeed, Rika’s ugliness is neatly, and no doubt deliberately subverted by the illustrations. In one panel, Rika’s mother shrieks about how horrid her daughter is; in the next we see said daughter as an absolutely adorable iguana in pajamas, looking up mournfully in anticipation of being mass-marketed to millions of kids worldwide as the latest kawaii sensation.

Similarly, when Rika tries on a pink dress, her mother insists it looks horrible on her — but…I mean, look at that little lizard with the dress! Awwwwwww.

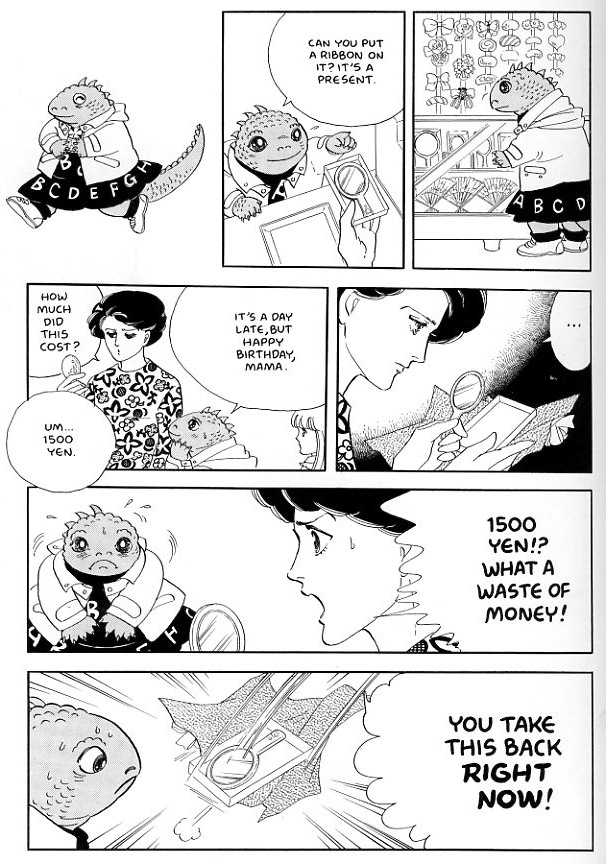

Rika is not only cuter than her human peers; she’s also more human — or, at least, she expresses a fuller range of emotion. Less tied to realistic fidelity, Rika’s feelings are both more exaggerated and more subtle than her mother’s, as you can see in this scene:

The confusion and indecision in the upper right panel; the tangible satisfaction in the second and third (where the unwieldy hands gripping the present emphasize Rika’s clumsy delight); the love in the fifth panel (again highlighted by the contrast between clumsy paw and liquid eye); the full-body despair and humiliation in the sixth — all of these are more genuine and more human than the mother’s porcelain interest, concern, and anger.

Later, Rika makes the contrast between people and animal explicit, noting that one of the advantages of being an iguana is that she’s begun to notice that other people are also animals. In other words, she is able to see the more real, more honest, kind of ridiculous, kind of appealing cartoon furry selves beneath the facade most people show to the world.

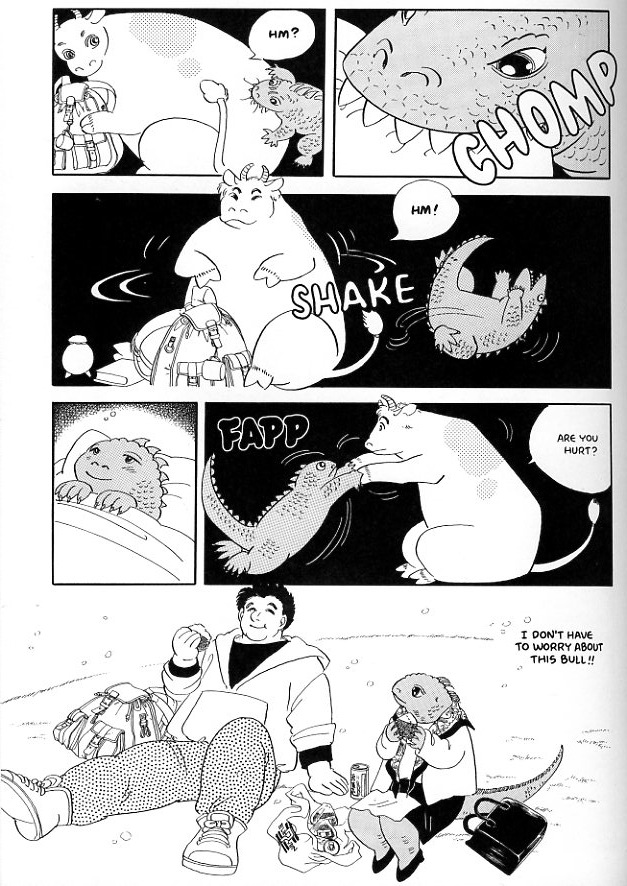

The above is maybe my favorite page in the story, showing the semi-imaginary courtship of Rika and her soon-to-be-husband. In dating other men, Rika was afraid that her dangerous iguananess would cause her to hurt them. But she doesn’t have to worry about this with Kazuhiko — less because of his physical strength, I think, than because of his emotional stability/obliviousness. The blissed-out iguana waking up in bed is obviously a highlight…but even better is that last panel, with Rika sitting besides Kazuhiko. I love Rika’s look of amazed, curious devotion…and I also love iguana/Rika’s pose. The legs tucked up under the napkin, the tail curving behind the cute skirt — Hagio has drawn one demurely sensual iguana.

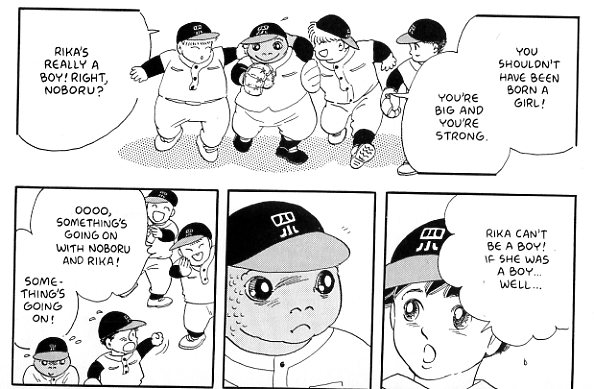

If Hagio here manages to make Rika very feminine, at other points she uses Rika’s iguana appearance to suggest boyishness.

Rika’s stockiness and rough animalness is here figured as butch, giving her difference a queer cast. As a lizard, her gender slips — she is boylike, and then her flirtation with Noburu comes across as not so much boy-girl romance as boy-boy, or boy-androgyne, or boy-lizard. Various other characters comment on Rika’s beauty, but since we aren’t allowed to see that for ourself (save for a couple of panels) the straight traditional genre heterosexual romance comes across as something else.

This is so even in the bull-lizard fliration above, which becomes, after all, an interspecies romance. And, for that matter, the image of lizard Rika sitting so femininely by the side of her love ends up as a kind of dress-up femininity, or drag. If Rika is a woman, it’s because of who she is irrespective of the body she happens to be in. Where some earlier stories (“Bianca” “Hanshin”) seemed to be suppressed narratives of queer despair, this comes across as an only slightly repressed story of queer fulfillment, in which the lizard never has to change into a swan in order to find her appropriately inappropriate lover.

________________

As just a final note…I think it’s worth pointing out that, as the use of Iguana-Rika shows, Hagio is at her best not as an artist and not as a writer, but as a manga-ka. I do like her drawing, and her writing is intermittently interesting, but her mastery really is in comics qua comics. Hanshin, with its use of the repetition of characters sequentially to mirror the theme of doubling; “Drunken Dream” with its thumbnail manipulation of genre through the sequential variation of visual tropes; “Iguana Girl” with its use of anthropomorphic animals to raise issues of emotion, gender, and humanity — those are all ingenious and subtle uses of the comics form. They’re not unprecedented necessarily — Bone is an obvious analogue to “Iguana Girl” for example — but they are handled with a degree of sophistication that’s very (very) rare in art comics today, much less genre work 30 years ago. Though I obviously have lots of reservations about her work in general and this book in particular, reading through A Drunken Dream has certainly made me want to see more of Hagio’s work. I do have two stories to go here, but after that…well, somebody needs to translate Heart of Thomas, damn it

Noah– are these left-to-right or right-to-left? These particular samples are ambiguous…

Whoops; sorry. They’re unflipped; so right to left.

It’s sad that you can’t see anything but clichés here. I have yet to meet a woman who has read this and not been moved. Again, I think you’re using the wrong stick to measure these stories.

This is weird; I saw lots of things other than cliches here! I overall liked it (with some serious reservations.) Maybe you’re commenting on the wrong story? This sounds more like a reply to Angel Mimic or The Willow Tree maybe? I know you went through them all at once; maybe there was a blip….

I could introduce you to women who don’t like various Moto Hagio stories. Brigid Alverson felt “The Willow Tree” was boring; I’m dead sure my wife would hate “Angel Mimic” and almost everything else in this book– so much so that I hesitate to even get her to try to read it, since she’d just be pissed at me.

The wrong yardstick thing…I only have the one yardstick, and that’s my own tastes and interests. I can appreciate that the stories may have been innovative in their day, but that makes them of historical interest; it doesn’t affect their quality or my enjoyment of them. I’m not opposed to genre work in general or shojo in particular. I came in very positively disposed towards Hagio after very much liking AA’. I spent upwards of 8000 words thinking about this book. I don’t think I’ve been unfair to her. If you have a particular perspective you think I’ve missed, or an understanding of the stories I haven’t considered, I’d be happy to think about that and respond to it…but a generalized statement of “you’re looking at these wrong” isn’t something that can get me to change my mind, or even to reframe my objections in a useful way.

I doubt you have time for a real back and forth though, since I know you’re crazy busy. But thank you for stopping by, and for putting together this volume. I look forward to your next project!

To comment on a five-year-old story, I’d like to say that I think it’s fairly obvious that the mother is simplistic because she’s being portrayed from the child’s point of view. A kid doesn’t perceive their parents as being well-rounded and three dimensional, they perceive what they see and what they directly interact with. It’s weird that you got many of the allegories and symbolism of the story but didn’t also get that the entire thing was told from the direct perspective of a daughter who thought that her mother hated her. That’s…….that’s kind of the whole thing.

I guess that’s one reading. You seem to be assuming that (a) parents never hate their kids, (b) kids can’t tell when they’re hated. I don’t think either of those things is true.

Also…even if it’s through the daughter’s perspective, it’s still through the daughter’s perspective. We don’t get to see the mother any other way, really. That creates problems in the narrative, as I discuss.