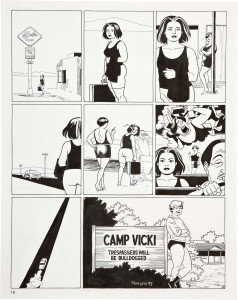

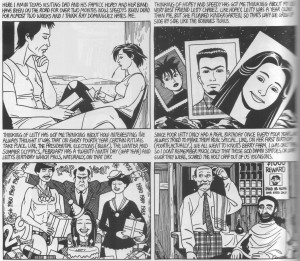

Some collectors will have noticed that Jaime Hernandez has been selling his original art via Heritage Auction Galleries since March this year. The general scarcity of Jaime’s original art is such that the prices achieved so far have sometimes been quite high with this handsome page from Chester Square (Love and Rockets #41, 1993) fetching $4780:

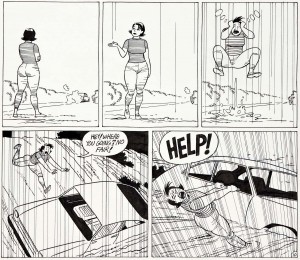

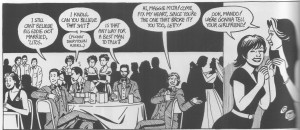

There is, however, much pleasure to be gained even from pieces of a more modest price. The following page from Love and Rockets #47 (1995, Chester Square) for example which cost a fraction of the page above:

Of course, there’s a yawning gap in the significance of the scenes being depicted with the former page showing Maggie’s departure from the site of some of the most distressing and debasing experiences in her short life, the latter nothing much at all. Yet the second page does demonstrate some of the more pleasant aspects of Jaime’s art, in particular that subtle play of expression which has become such a hallmark of the series.

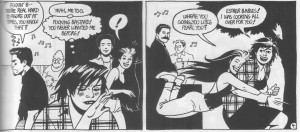

There’s Maggie’s suspicious stare directed outwards in the first panel enticing us in, the quizzical look as she examines Danita’s son in the second panel and the kid’s spaced out expression heightened by the directionless bubbles emerging from his head.

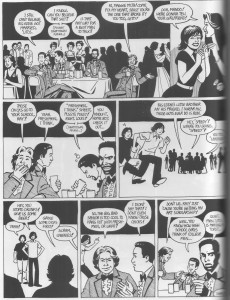

You can see these aimless bubbles deployed in a somewhat different vein as Maggie loses her car in this sequence from Bob Richardson (Love and Rockets #48, 1995)

When she is viewed at a slight distance, Maggie’s eyes are depicted by just two dots, her feelings expressed by her eyebrows, mouth and body language. She’s leaning forward with one brow arched in the second panel, eagerly sitting up and smiling in the third.

Jaime is having a bit of fun here but he’s also paying careful attention to the work at hand. The bottom tier of the page is an excellent piece of theater with the final panel showing Maggie and her sister, Esther, with mirrored looks, each with an eyebrow raised as if to imply some familial learned behavior. And isn’t it strange that Maggie is pointing her finger straight out in the panel right above one where she is reminded by Esther that she recently saw a friend stick his “pipi” into another guy’s butt.

The lengthy periods between Jaime’s publications is such that it is all too easy to forget what these characters looked liked in earlier episodes. This is particularly true of Maggie and Hopey who have been revised quite thoroughly by the artist’s gradual refinement of his inking style over the years; an approach which has led, in more recent times, towards a kind of confident reduction in his technique. Hence the startling difference in Maggie’s appearance in the initial pages of Wig Wam Bam (Love and Rockets #33, 1990) before she “disappears” for most of that book ….

….and her reappearance in Chester Square in the mid 90s (Love and Rockets #40 up, see original art above); the new style heralding not so much a rebirth but a descent into a personal hell of beatings and joyless sexual intercourse.

Wig Wam Bam (WWB, 1990) was, among other things, an examination of a number of absences: the absence of Maggie from a series which had hitherto focused on her, the absence of certainty and the absence of life. Maggie is merely a memory in these pages, just as her long dead and one time best friend, Letty, is a memory trapped in a box at her father’s house.

This is the same young friend whose history, death and remembrance gives name and meaning to that long novella and who we first saw giggling with Maggie at the end of The Death of Speedy Ortiz (DOS, 1987) over twenty years ago…

…two extinguished lives (Speedy and Letty) ominously mirrored and separated by the diagonal space across the final page of that beloved early story…

…recalled once again in the form of lines of correspondence running through the body of Jaime’s latest comic, “Browntown” (2010). Thus first a cryptic yet “physically tangible” person (in DOS), then recalled in the pages of a memoir (in WWB) before resurfacing in the pages of Maggie’s letters; a life almost lived in reverse

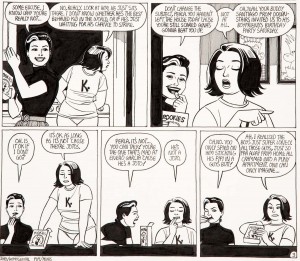

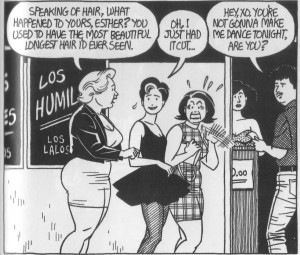

Such changes are also true of a character like Esther who undergoes a transformation both in her physical appearance (ageing and de-ageing) and in her wardrobe; changes which reflect a molding of her personality and the reader’s sense of the passage of time; the idea that something has occurred to her and an assortment of characters while we following the main thread of Maggie’s life.

When we first see Esther, she is a young girl paying a visit to her sister, drifting towards an infatuation with Speedy and, perhaps, becoming the inadvertent cause of his death. Years later and her hair has been trimmed down because of an altercation with a “gang of girls”, now visiting her sister before she gets married.

In the page of original art above (second from top) she is the more glamorous younger sister dressed in a figure hugging turtle neck, sporting a shock of dyed blonde (?) hair with eyes laced with thick mascara.

So time (moving forward ever mercilessly for both the artist and his creation) is only occasionally spoken of and much more often shown to have passed; a long accepted part of Jaime’s (and his brother, Beto’s) comics. This gradual accretion of detail, this deepening of the characters over the years in concert with their creator’s abilities has resulted in one of the most engaging depictions of time in American comics. These characters grow old with us in the most natural and realistic of ways, through unexpectedly revealed details, unsolved mysteries and memories reinforced by flipping through old scrapbooks. It is only with that extra effort that we remember how much they have really changed. And as with life, there’s that sense of apparent disorder, that feeling of something organic and unengineered. Something “real”.

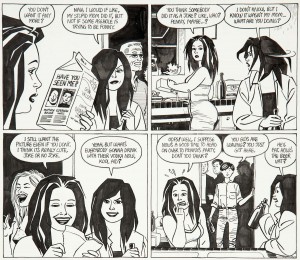

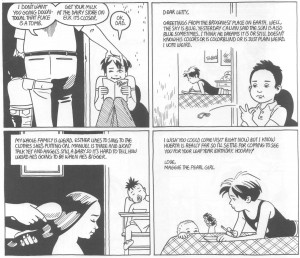

The modest page of original art which I mentioned at the start of this article shows the light-hearted aspect of Jaime’s art, that counterpoint which eludes many of his peers, the stuff that alleviates and accentuates the complex chronology and weight of depression that infects books like Chester Square, Ghost of Hoppers or his most recent stories, “Browntown” and “The Love Bunglers”. We see the same precise use of facial and bodily expression again in the following scene from that last story…

…where these markers are suddenly subtracted in the pair of silhouettes which form the middle tier of the page; a penultimate confrontation and coda to “Browntown” where Maggie awaits Ray’s judgment, their faces absent and our feelings and impressions set in motion and invited in, just as they have been invited in for the last 30 years during the creation of this American masterpiece.

______________________________________________________

Related Material

Jeet Heer on “Browntown”. Perhaps the best review of the book available at this time

Tucker Stone and Michel Fiffe on Love and Rockets: New Stories #3

The Jaime Hernandez Chronology by Mark Rosenfelder

One of the coolest things about working in the Fantagraphics offices for six years: Getting to read the complete Ghost of Hoppers from the original art as the pages came into the office, when no one was looking.

whoa.

As fas as I can tell, Jaime hasn’t sold any pages of original art outside the first 50 issues of Love and Rockets. Since I think he’s been doing his best work in the last 10-15 years or so, that’s also the original art which I’m most interested in. The reverse is the case with some (many?) L&R art collectors though, since a lot of them are nostalgists who stopped reading L&R in the early 90s or something like that (I presume during the B&W bust years).

thank you for this smart & sensitive analysis!