How useful is Charles Hatfield’s notion of “ironic authentication” for understanding the autobiographies of women cartoonists?

I ask that question provocatively, but sincerely. The concept is worked out in the comics of male cartoonists: Hatfield first offers a compelling account of Harvey Pekar’s American Splendor, claiming it as the origin point of a comics tradition of realist-naturalist autobiography (which he just calls realist). He then opposes this naturalism to the fantasy mode typically associated with “mainstream” comics, outlining the transformative impact Pekar’s naturalism had on the scope of the “comic book hero.” He next tackles the far more theoretically ambivalent territory of autobiographical subjectivity, beginning by emphasizing the ways in which comics resonate and amplify autobiography’s inability (identified and emphasized by Autobiography Studies in literature) to escape the inherently fictive attributes of narrative subjectivity: “comics pose an immediate and obvious challenge to the idea of non-fiction.” Dan Clowes and the heightened formalist self-awareness in Just Another Day is read first, for insight into how the unavoidable fictitiousness of cartoon selves “distills and mocks Pekar’s ethic of fidelity to mundane truths,” then linked to R. Crumb’s The Many Faces of R. Crumb in order to assert that the seemingly unanchored “fictitiousness” of Clowes’ perspective actually is a “truthful” representation of the plasticity of identity. This elegant and theoretically savvy series of readings culminates in an examination of Gilbert Hernandez’s parodic “My Love Book,” which “teases the reader with a disjointed series of confessional vignettes, between which his visual personae shift so radically that we can confirm their common identity only through the repetition of certain motifs of in dialog and action” and which ends with an ironic suicide that “adverts to the limitations of autobiography” and “muddies its own assertion of truth.”

Hatfield concludes that the modality linking these disparate representations of non/fictional selves is irony:

If autobiographical comics take as their starting point a polemical assertion of truth over fantasy, then these comics serve to reassert the fantastic, distorting power of the artist’s craft and vision. They carry us to the vanishing point where imagination and truth collide. Yet these pieces still demand and play on the reader’s trust: they still purport to tell truths. Crumb, Clowes, and Hernandez, finally, do not disallow autobiography as such, but ironically reaffirm its power by demanding recognition of its implicit assumptions.

[…]

This irony comes into sharper focus if we invoke Merle Brown’s distinction between the fictive and the fictitious: a story may be fictive, yet truthful, insofar as it “implies as part of itself the art of its making;” in contrast, a story (autobiographical or otherwise) that does not acknowledge its own making is merely fictitious…

We might call this strategy, then, authentication through artifice, or more simply, ironic authentication: the implicit reinforcement of truth claims through their explicit rejection…[the three tales], paradoxically, glorify the self through a form of self-abnegation – that is, through the very denial of an irreducible, unified identity, one that cannot be falsified through artistic representation.

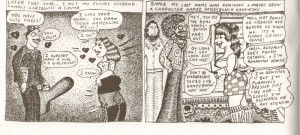

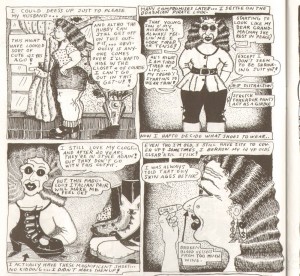

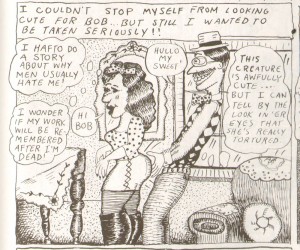

References to the comics of Aline Kominsky-Crumb appear throughout Hatfield’s analysis, emphasizing the “grotty” realism, the “psychosexual and scatological details,” and the “excesses of disclosure.” But he doesn’t read her comics closely in light of this theory of “ironic authentication.” My sense of Kominsky-Crumb’s early autobiographical Bunch comics is that they do not operate in this ironic mode laden with formalist self-consciousness; if they can be read as ironic at all, it is as parody of conventional, gender-normative bourgeois narratives and archetypes of femininity, specifically post-feminist narratives of feminine angst (including Cathy) but also pre- or non-feminist fantasy narratives including fairy tales, harlequin romances, and the (archetypal) consumptive female body of late capitalism (fashion models, celebrities).

Parsing such parody does not require “recognition of [autobiography’s] implicit assumptions.” But I question whether this is irony at all: the references to and exaggerations of gender-normative bourgeois ideals do not serve to heighten disjunctures between Kominsky-Crumb’s experience and the normative benchmarks, but rather to rip away the comforting facades and fantasied resolutions that bourgeois narratives offer in response to the contradictions of female subjectivity.

In reality, Kominsky-Crumb is very beautiful; her self-representation, especially in the first panel, with all that cellulite, is a grotesque distortion of her appearance, as in the Pekar and Clowes. Like Pekar, Kominsky-Crumb “opposes the fantasy mode” of bourgeois narrative through her use of exaggeration and the grotesque. But unlike Pekar, for whom that caricature represents “a process of becoming an object, indeed a parody of oneself” that allows the cartoon to be seen as an externalization of an internal self-concept, the caricatures in Kominsky-Crumb make reference to a specific, pre-existing external image, the cultural ideal of the feminine body that structures and informs the process of becoming a woman.

Although it has been restated and recast innumerable times by feminists in the intervening 60 years, the classic articulation of this is Simone de Beauvoir’s, in The Second Sex. Writing in the years immediately after the Second World War, de Beauvoir described the function of body image in the development of female identity using the then-trendy language of Oedipal psychoanalysis and with reference to the subjugated status of women in mid-century society:

The main difference [between a doll and a penis] is that on the one hand, the doll represents the whole body, and on the other, the doll is a passive object. On this account, the little girl will be led to identify her whole person and to regard this as an inert given object…the little girl coddles her doll and dresses her up as she dreams of being coddled and dressed up herself; inversely she thinks of herself as a marvelous doll. By means of compliments and scoldings, through images and words, she learns the meanings of pretty and homely; she soon learns that in order to be pleasing she must be “as pretty as a picture;” she tries to make herself look like a picture, she puts on fancy clothes, she studies herself in a mirror, she compares herself with princesses and fairies…this narcissism appears so precociously in the little girl, it will play so fundamental a part in her life as a woman, that it is easy to regard it as arising from a mysterious feminine instinct…[In woman], there is from the beginning a conflict between her autonomous existence and her objective self.

Although the Oedipal narrative lacks resonance today and the tireless efforts of feminists to break up this dynamic have been partially effective, the idea of an inert, ideal body image still exerts great power over girls and women – and increasingly, in our media saturated age, over boys and men.

For female autobiographers, then, the externalized drawn body does not create a blurring of the outside and the inside, it merely represents a pre-existing dynamic. It consequently does not challenge the idea of non-fiction, because the ubiquity of that external representation and its centrality to “becoming a woman” in the first place is a fundamental truth of female experience. The problems of an externally imposed ideal of the body are more than formal and philosophical in the context of female body image; they resonate on lived female bodies in visceral ways, unlike the formal, literary implications that emerge when men play with the trope. The demise of the Oedipal narrative did not consign anorexia to the same status as hysteria.

What Kominsky-Crumb articulates, then, is not the inherent difficulty of identifying with an external representation of the body, but an over-determined, excessive identification with the external representation. Representing the self “becoming an object” is not a ironic, distancing process that exposes the unrecognized fictions of a realist, self-identical identity or illuminates the plasticity of identity, but rather one that underscores the restrictions on that plasticity imposed from outside. In fact, “becoming” is the wrong tense entirely; instead it is “having already become,” or perhaps “having always been.”

From this vantage point, the imperative for Kominsky-Crumb’s comics to “imply as part of themselves the art of their making” in order to tap into the truths of identity seems less necessary. By Hatfield’s measure, this would make Kominsky-Crumb’s comics “fictitious,” trapped in the epistemological aporia of the represented first person and unable to make truth claims for its representation of feminine experience.

But that would be much too harsh a reading (and I want to stress that is not a claim that Hatfield makes about Kominsky-Crumb; just an implication). I don’t get the sense from reading Kominsky-Crumb’s work that her self-representation is less “true” because it eschews that formal self-awareness or ironic detachment that Clowes et al. exploit to enhance the truth of their representations. I want to suggest, then, that what the cartoon idiom’s formal properties foreground most fundamentally is not a space between truth and fiction that must be mediated and filled in by irony, but rather the fundamental truthfulness of the fictional mode, something which must be reconciled in men’s autobiography with that gender’s conventional unfamiliarity and discomfort with insistent embodiment. Hatfield’s “ironic authentication” is not mediating the tension between the fiction of autobiography and experiential truth; it is mediating the instability and discomfort of autobiography’s central theoretical truth: the extent to which experience and identity are cultural fictions.

Hatfield gets close to this in his assertions regarding the plasticity of identity: “In each case, the self-assertion of the author rests on the plasticity of his self-image, on his awareness of the slipperiness of individual identity. The core identity of each is precisely what cannot be represented, and it is this very lack that, ironically, prompts the project of self-representation.”

But the lack is very specifically gendered male – the irony arises from the incongruities between male experience and comics representation. The representation of female bodies feels far less incongruous: insofar as such a thing as a “core identity” exists, for a woman it is always already fragmented into the spheres of internal perception and external ideal, and the external ideal not only can be represented but is constantly represented, in both fiction and life. The demand that women identify unproblematically with external representations of ideal bodies is not made first by comics, it is made first by culture, and it is virtually unceasing (and again, to be clear, this demand is increasingly extended to men). Women, culturally speaking, are denied the luxury of experiencing their “core identity” as transcendent and disembodied: “woman” is simply too coded by physical attributes and the act of being gazed upon for women to ever experience a fully disembodied self, autonomous from culture, body, and Other.

Such a reading emphasizes the extent to which those aspects of the comics idiom which Hatfield identifies as generating tensions and contradictions in the context of male subjectivity are in fact entirely mimetic in the context of female subjectivity. The formal properties of comics resonate mimetically with female experience – but that mimesis is not “naturalist.” Comics autobiography by women operates in a mode we might call abstract realism: the fictions of the idiom illuminate not the inherent fictiveness of autobiography, but the inherent fictiveness – constructedness – of subjectivity itself, while underscoring emphatically that that fiction is fact, lived experience. For women, the resonant and rich contradictions of body and self are not the stuff of maximally self-conscious, ironic, counterintuitive and theatrical literary fiction – they are an entirely unironic, discursive and fictional but fully authentic, representation of the experience of a written life: Life writing.

_______

Update by Noah: The entire roundtable on Charles Hatfield’s book is here.

This is a great essay Caro. Thanks for posting it.

I’m trying to figure out how it works with Moto Hagio now…I’ll try to work it through and maybe comment later….

Thanks Noah! It’s still a draft, honestly, only a couple of iterations in, so if you get stuck on anything let me know ’cause I’m sure it can stand some revision. I’ll look forward to hearing your thoughts on Hagio.

I swear I hadn’t seen this until 5 minutes ago, but here’s Aline Kominsky-Crumb talking about the imposition of an external ideal of beauty that she didn’t match. (That’s Diane Noomin at the beginning of the clip; the relevant bit starts about minute 2:45.)

So with Hagio; I think the ideas you’re using here fit interestingly onto her story “A Drunken Dream.” Drunken Dream isn’t autobiography in the traditional sense, but it’s obviously exploring autobiographical themes. And it does that by literally mapping one person’s trauma onto the universe; the rift in time space is based on/tied to the main character’s abusive relationship.

So in male autobio in Charles’ formulation you’ve got the truth as the space between truth and fiction. In Hagio, the truth is the lack of space between subject and object; out there and in here are the same. Rather than an inaccessible self approached through the subjective distance of irony, you have an all-too-accessible self crushed by the objective weight of trauma.

I wish my Lacan were better, because that seems like the lens through which this should be viewed in some sense. I just don’t know how to do it. I like how you used the lack in your discussion of the autobiographical cartoonists; irony sort of becomes the phallus in that reading, right, substituting for the lack…. Whereas for women there’s no substitution; the lack is its own phallus? It’s own real? In any case, in this formulation women are actually more in touch with the truth, which is that the (fictive) universe is the self, and that there is no other self, whereas men need first to lose the self and then replace that self with irony to get to the same place.

That’s definitely Freudian too…except flipped sort of. The woman ends up being natural (because closer to the imaginary) while the man ends up being broken (lacking the lack.) Irony is a non-penis substitute for those who haven’t yet been castrated into wholeness.

Or quite possibly that doesn’t make any sense at all. What think you?

Noah — I think it sounds like the start of a very interesting reading of Hagio. The feminism in my post is extremely Lacanian, so yes, I agree with that, and also with your sense that something’s been flipped. The Lacanian feminists definitely flipped around the notion of “there is no sexual relation” into something that privileged lack as the supplement for the male ego. I don’t remember the primary sources for that, though; I’ll have to look. It’s probably covered in Elizabeth Grosz’s Lacan: A Feminist Introduction and possibly in the Silverman I mentioned last week…

I also have to say that this sentence makes me immensely happy: “Irony is a non-penis substitute for those who haven’t yet been castrated into wholeness.” It makes me want to write a manifesto called “Castrated into Wholeness.”

What I really need is not Lacan for feminist but Lacan for complete idiots. But the Grosz sounds like it’ll have to do….

Now I know what to answer to those well-meaning idiots, who ask why do I draw myself so ugly in my own comics. A question which I find as impolite as ignorant.

Or think of Brétécher. For me, her image of women is more than true. Instead of pretty pictures she shows us the complex core of women.

Excellent piece, Caro. Charles’ distinction between fiction and the also fictitious grated with me and you have articulated an important reason why.

Also, I’m not entirely sure I quite buy the concept of irony as applied generally even to male autobiographical cartoonists — it assumes a neutral level of representation that not everybody necessarily aspires towards.

(Hi Johanna!)

Hey Matthias. Which male cartoonists were you thinking of as exceptions? Was there anyone in particular?

Johanna — Give ’em hell! It is definitely an impolite question! It shows such naivete, though, about the complexity of women’s self-representation. The fact that people aren’t aware of how intimate a question it is … this may be a failure of second wave feminism, or one of the effects of 3rd wave’s media fascination. You’ve given me something new and fascinating to think about!

I’m fairly new to comics – I’ve managed to get generally familiar with the US alt-comics world but not much more — I had not seen Bretecher and will definitely go look, and the work on your site is beautiful. I’m so glad you commented and drew my attention to both.

Thanks, Matthias. I’m going to have to think about how I feel re Charles’ point about irony in general; my reading was very linked to this perspective. As I’m sure you know, American popular culture right now is saturated with irony, and I generally tend to have a strongly negative reaction to it, although less so in its more self-conciously “arty” instances than in the broader forms that turn up in hollywood films and TV. I wonder if it’s assumption of a “neutral ground of representation” may be part of the reason why I react so badly…very interesting idea.

“Charles’ distinction between fiction and the also fictitious grated with me and you have articulated an important reason why.”

Well, it *does* seem like a rather old-fashioned distinction in a world in which no neutral ground of representation exists.

I hope my model of “ironic authentication” (which really describes a particular type of or motive for self-reflexivity) can be of some use without assuming a neutral ground of representation.

I’ll have more to say about Caro’s post (the most provocative and useful of this roundtable so far IMO!) next week.

” (the most provocative and useful of this roundtable so far IMO!)”

Yeah, Caro’s tough to compete with, bless her….

Thank you, gentlemen. :) I’m glad it’s provocative and useful.

I feel sure it would not have been nearly as provocative or useful without Charles’ excellent articulation of ironic authentication to work from: it relies very heavily on the strength of his original theorization, as it’s really just fine-tuning…

There are a couple of things you might find interesting about Kominsky-Crumb. The first is that she can only conceive narrative as autobiography; contriving characters and creating fictional situations is, by her account, a leap she isn’t able to make. The second is that she finds herself incapable of accessing her draftsmanship skills when she cartoons. She can utilize them when she paints, but comics for her are an entirely expressive undertaking. She can’t create the imaginative distance of fiction, or make use of the objective distance of craftsmanship, all of which I believe bolsters the points you make here. TCJ cover-featured an interview with her in issue #139; I recall that she talks about these matters there. I just checked, and you can still order the issue from Fantagraphics. (Here I go, busting your book budget again.)

Robert, that is indeed fascinating. But my book budget is safe: I’ll just send Chris to the storage unit for that issue of TCJ…LOL. Thanks!