I’ve recently begun teaching cartooning again. That event, and the approaching season of commerce gift giving have persuaded me to take a look at some interesting books that have a tangential relationship to the subject. There are plenty of books out there that directly address the processes and skills of cartooning, with greater or lesser results (I happen to think Scott McCloud’s Making Comics is the clear champion in this category) but for the purposes of this post I’ll be covering those books that might not have quite as direct a connection.

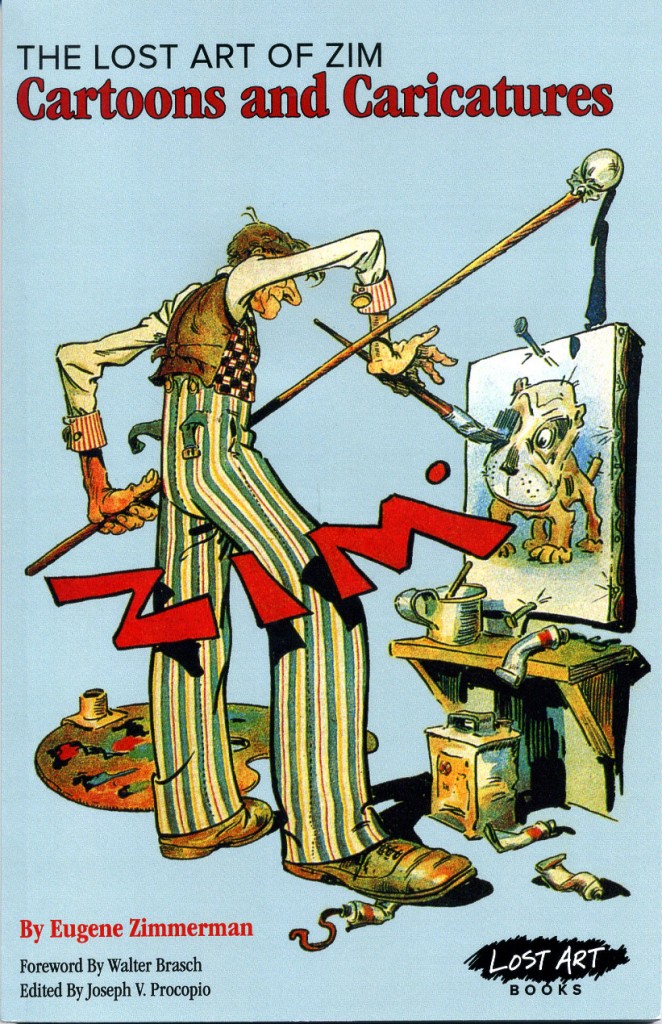

First up is a book by Eugene “Zim” Zimmerman’s The Lost Art of Zim: Cartoons and Caricatures, originally written and released in 1910 and recently reprinted with supplemental material by Picture This Press. The book, collected from material Zim contributed to America’s first correspondence course in cartooning, is a bizarre mixture of practical tips for the aspiring gag cartoonist of 1910 and advice for life and development of such a fellow. In addition to the practical insight into the process and industry of the time, and the beautiful examples of Zim’s caricature skills, it also gives the modern reader quite a view into the popularity of cartoonists (or “caricaturists”) at the time, as in this eye-popping quote:

It is natural for a fond mother to ask: “What shall I do with my son to make him a caricaturist?” The question is a hard one to answer, for no two boys follow the same course through life to attain the same ends. Therefore, it would be impossible for me to lay out a course for a beginner to pursue terminating in certain success. It would be too much like prescribing a course of treatment for a chronic disease- much depends upon circumstances. Events arising in politics may afford the young artist an immediate opportunity to come to the front- the making of war heroes cannot be forseen. So it is with great artists. If the youth possess an artistic nature, love for fun, perseverance, and can withstand disappointments, then (perhaps) you can make a caricaturist of him.

The world is such a different place now–we’re so removed from the view of cartoonists as national superstars, celebrity visualists on par with today’s celebrity film directors, that it is sometimes difficult for this particular modern reader to determine when Zim is dispensing straight-faced advice, and when he is taking the piss:

The life of a caricaturist is much the same as the life of the proverbial plumber- both command large salaries.

The focus of the practical material is as often on how to lead a hardy life as it is on any particular rendering technique or skills building, but the book is also chock full of bon mots and anecdotes honed over a lifetime of delivering solicited and unsolicited advice:

The more you boil down your sap the richer will be your syrup. Likewise with a caption.

In Caricaturing you will notice your own face gradually reflects the leading feature of the person you are sketching

And possibly the most interesting (and revealing) piece of advice in the whole book:

When possible avoid such offensive adjuncts as warts, corns, bunions, club feet, mutilated hands or anything that is likely to retard the fun in your pictures.

This book won’t hold much practical use for the modern cartoonist, but it is a fascinating peak into a time past, and the work of a long-forgotten master craftsman. It would be a good gift for the historically-minded cartoonist, or anyone interested in the origins of bigfoot styles.

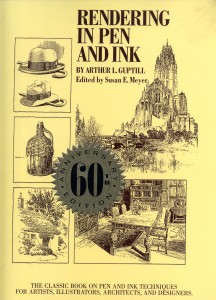

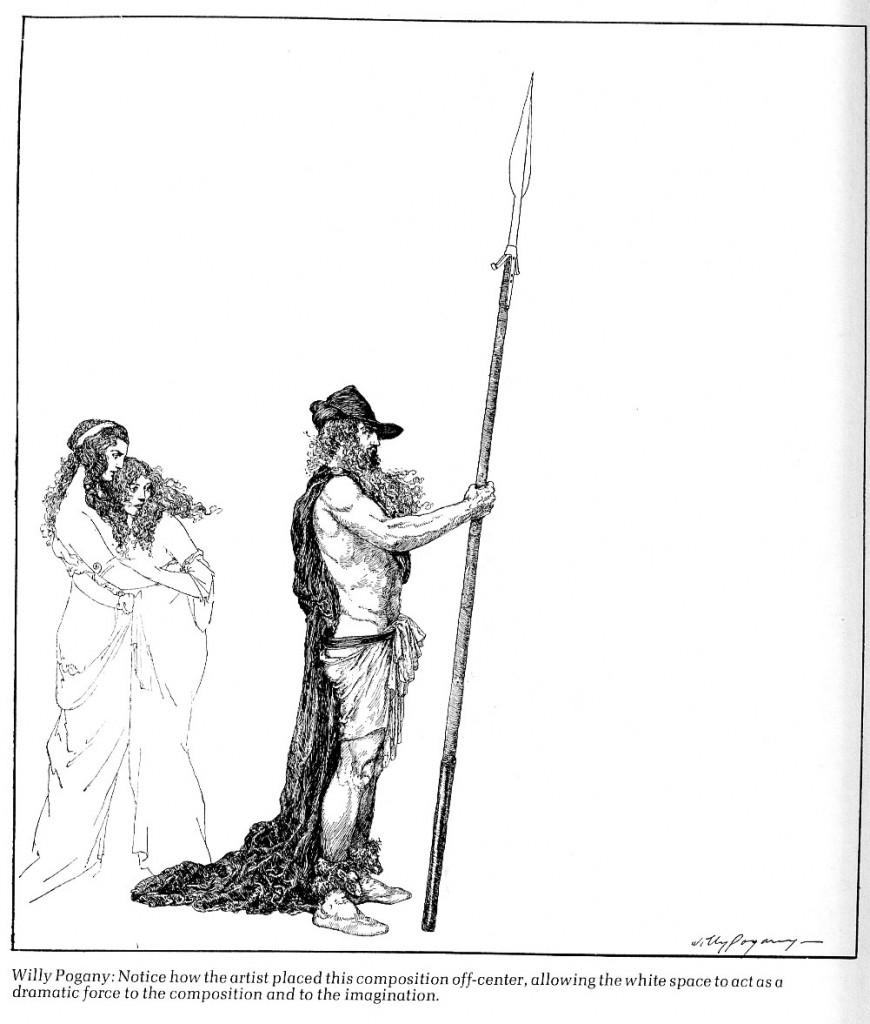

Next up is Rendering in Pen and Ink by Arthur L. Guptill, a book which I’ve now owned several copies of, as it’s always had a tendency to walk out of the classroom. This book is quite simply the most comprehensive and helpful how-to art book I’ve ever seen. Originally published in 1930, at the height of the popularity and use of ink drawing, it presents a comprehensive survey of techniques for a wide variety of potential ink styles, illustrated with Guptill’s demonstration drawings, and drawings by a bevy of American pen and ink masters, including Willy Pogany, John R. Neil, Rockwell Kent, James Montgomery Flagg, Walter Jardine, Franklin Booth, Aubrey Beardsley, and many more.

Although it has become less and less so over the past decade, comics have been tied to mass reproduction, and therefore easily reproducible black lines, for a century and a half. And for those of us who love not only narrative art, but also ink drawing itself, it can be fascinating to peek into the golden age of Western ink drawing and survey the methods used at the height of that period. American comics have for a long time been based primarily around contour lines and bold use of blacks, this coming out of newspaper adventure strip traditions in which the contours served as a container for the color. Strangely enough many American artists have carried this method of working and value balancing even into their black and white work, or else have simply laid simplified, repetitive patterns or textures into the work without really exploring a fuller range of implied value or dense, representational texture. (Obvious exceptions being the work of Cerebus background artist Gerhard, and a wide variety of manga artists, who had the economic advantage of many assistants providing those backgrounds).

Anyway, this book is fabulous, and takes up so many issues relevant to anyone working in pen and ink, that it’s probably pointless for me to do anything other than recommend that, if you or someone you know is interested in the topic, you pick up a copy of the book. It’s cheap, it’s huge, and it’s incredible.

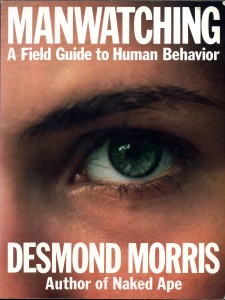

Next up is a book that has the least direct connection to cartooning, but been the greatest aid to my own work, and is generally the first book I recommend to other cartoonists: Desmond Morris’ Manwatching.

A coy expression (above) consists of two conflicting signals: a “shyly” lowered head and a bold stare. And it is this which distinguishes it from a truly shy expression, in which both head and eyes are lowered.

Desmond Morris is a zoologist and animal behaviorist whose long career has been marked by an increasing focus on human interaction. The book itself is a lavishly illustrated 320 page compendium of observable human behaviors that categorizes the observable with a deft intelligence that will change the way you see the actions of those around you. Reading this book for the first time, I felt like I was gaining access to an invisible language happening at the point of every human interaction, a language I involuntarily spoke, sometimes interpreted, but was now laid out naked before me.

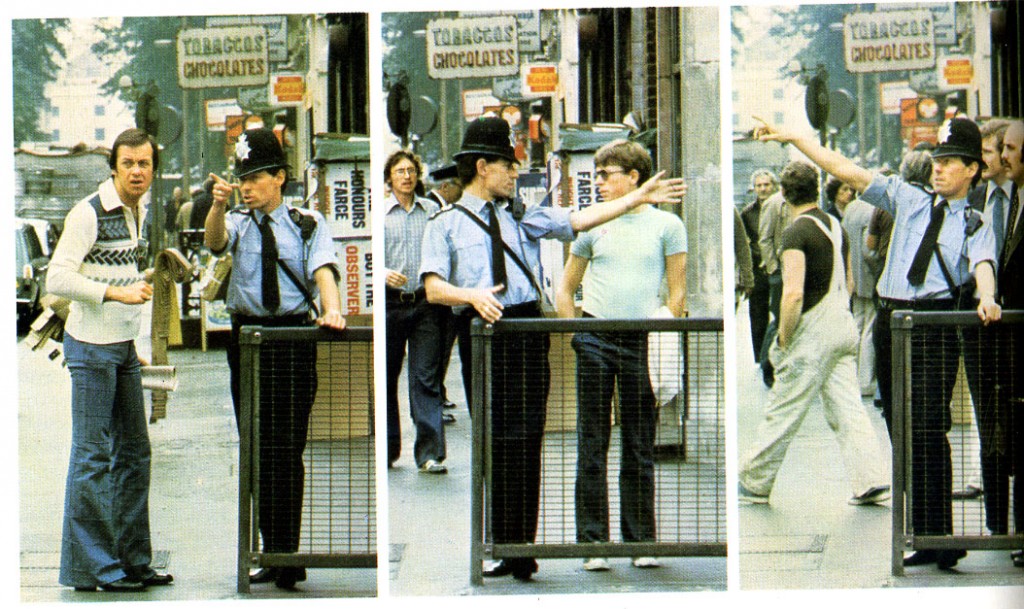

The sections that succesfully catalog and link what might seem like unrelated behaviors are the most impressive and definitely applicable to cartooning, but the eighty-odd pages devoted to gesture and physical communication have a more direct application.

The Forefinger point is a Guide-sign showing the position of something, while the Hand-Point is used to indicate the course to be taken. The higher the object, the higher the forefinger points, as if it were an arrow about to be fired at a target.

Rather than a list of gestures or poses to be memorized, the book provides potentials for awakening insights–openings into a world of greater observation.

As is befitting a book of such scope, he even has some interesting things to say about art, including this passage regarding “supernormal proportions”:

…in adult art, only on a few occasions in the history of painting and sculpture have the goals of artists been to reproduce as accurately as possibly the outside world. In a picture, man is freed from the demands of reality to a supreme degree. If a figure is running, it can have incredibly long legs; if it is mating it can display a huge, abnormally long penis; if it is threatening, it can open a vast mouth to reveal impossibly large fangs.

Although the book appears to be out of print currently, you can still find used copies for $30 on Amazon, and many other places–I picked mine up for a dollar at a swap meet. There are a million of them out there, so keep your eyes peeled.

Last up is the two book set that keeps on giving, the books that almost never were. Walt Stanchfield taught life drawing classes at Disney’s animation studios for over twenty years, and the two massive Drawn to Life books collect the photocopied handouts he worked up for his students each week. These handouts, preserved by students and finally collected in book form last year after years of bootlegging, have no shortage of artistic and gestural revelations. Having read the books only once, I feel like I’ve barely skimmed the surface of the knowledge lurking in the text. What is the essence of a gesture? How do you capture that essence? How to translate observed information into your drawing from imagination? It’s all here. I can’t recommend Drawn to Life enough.

Finding your own copies:

Oh God…I MUST have the Guptill book!

Hey, I have the Guptill on my desk! I love that book. I wonder if it was you who recommended it to me when I was talking about How to Pen and Ink (that great manga inking book I reviewed a while ago). It’s sooooo good and a lot of fun.

Alex- It’s a fabulous book- great illustrations and explications of various techniques. And unlike many instructional books from the time period, the text is very conversational and helpful rather than stodgy and didactic.

Vom- I looked it up- looks like it was recommended to you via Nick Mullins- although I’ve certainly recommended it enough times myself :) It’s one of those books that’s so thorough that every other pen and ink book seems to be derived from it in one way or another.

Have you seen my review of Making Comics, Sean? I really didn’t like that book…

Noah,

I read your review when it initially ran in the print edition of TCJ.

Funny how I can agree with most of your criticisms of the book, but have a completely different conclusion about the utility of the book as a whole. I found Making Comics very useful personally when it first came out, and now find it very useful in my teaching. It’s not a perfect book, and it’s not a completely innovative book, but it does manage to synthesize a tremendous amount of information into a digestible format, and for that reason, if someone’s looking for a book literally on how to make comics, it’s on the top of my list.

And, really, what’s the competition? The Jessica Abel and Matt Madden book has some very useful exercises at the back of every chapter and a few useful sections, but is stymied by clunky layout and poor drawing that attempts and fails to successfully emulate the variety of styles they talk about. There’s a lot to like about it, but it involved wading through much familiar territory.

And then there’s the Eisner books. I know some people must like them because they stay in print, but… I don’t find them terribly useful. Although, at least like McCloud’s work, Eisner’s books expanded the vocabulary a bit.

You read it, yet you agreed to write here anyway!

I must admit, I haven’t seen the other books, so wasn’t really doing a comparison. It depresses me to think they’re even worse….

>>You read it, yet you agreed to write here anyway!

Maybe in exchange for writing for HU I should have exacted a promise from you never to review any of my comics instead :) The hardest part of the slagging would be realizing that 90 percent of what you were saying would be completely on target, even if I disagreed with your overall conclusions.

>>It depresses me to think they’re even worse….

I think it’s just the nature of the beast. No one has all the skills required for a project like that- it would take a well-funded, well organized team to put together a really comprehensive text on virtually any subject. I mean, how often do you see such a thing? How many text books or how-to books on any subject are really worthwhile?

Don’t get me started about text books.

The problem is more to do with the genre than expertise, I think. I could explain at length, but I will spare you.

Have you read the Shojo Beat Manga Academy? It’s kind of silly, but I like it as a how-to-book much more than McCloud. (I am entirely self-taught and inhale these books all the time.)

No, I haven’t seen that one. Worth checking out then?

Oh, and I really should have mentioned another favorite of mine in this here post, the ridiculous (and delightfully useful) “Even a Monkey Can Draw Manga.” Despite the fact that it’s riotous parody, it actually has some excellent advice!

Creative Illustration by Andrew Loomis.

I think so. It covers things from a manga perspective, of course, but it goes through most of the major issues of comic creation–characters, plot, layout, inking. I like it because there’s a throughline by one artist (the panda), and then interviews and tips by various other artists. A lot of them come from the creator of Absolute Boyfriend. I find the advice from working mangaka to be rather different (and more practical) than from more theoretical folks like McCloud, whose interest seems more what it ought to be than what it is. if that makes sense.

Vollsticks-

Yeah, I should have worked in a Loomis book as well. I’ve found Figure Drawing For What It’s Worth really useful, and it probably should have made the cut. What do you like about Creative Illustration?

>>>like McCloud, whose interest seems more what it ought to be than what it is. if that makes sense>>>

Total sense. In the vein of super practical, “this is how I made this” style books, I found “Pen and Tone Techniques” in the “How to Draw Manga” series full of useful information, but quite narrow in scope and application.

I loved Manwaching! Morris very accurately depicts all sorts of human behavior. And although at first I was a little narrow mined and thought why would I need a book like this, I quickly realized that I was better able to capture facial expressions and gestures I couldn’t quite get right in the past! Thank you for all the other recommendations!

Charllote-

I found the same thing- very strange how having your attention drawn to a behaviour can put said behaviour in such stark relief. All the sudden I’m seeing these thinly-coded statements all around me… Anyway, glad to meet another Manwatching fan, and be sure to let me know what you think of the other books!