Les soeurs Zabîme (the Zabîme sisters) by Aristophane [Boulon]

Can you imagine yourself in Kupe’s lighthouse (that ideal comics library filled with books that don’t exist in Dylan Horrocks’ Hicksville)? I do sometimes, but, even if I wholeheartedly agree with Kupe’s point of view (which is: “The official history of comics is a history of frustration. Of unrealised potential. Of artists who never got the chance to do that magnum opus. Of stories that never got told – or else they were bowdlerized by small-minded editors…”) my particular lighthouse has a few books whose content does exist, but isn’t available. Books like Santiago “Chago” Armada’s Sa-lo-mon, or Rafael Fornés’ Sabino, or James Edgar’s and Tony Weare’s Shannon Gunfighter or Isepinal and the Apaches, or Héctor Germán Oesterheld’s and Francisco Solano López’s Amapola Negra (Black Poppy), or Martin Vaughn-James’ The Park…

Cuban artists “Chago” Armada (left) and Samuel Feijóo (photo published in Signos # 32, 1984). The drawing is Armada’s.

This is, of course, the editor and publisher in me. Since I’m neither I insisted several times with my good friend and micro publisher of Libri Impressi, Manuel Caldas, that he should publish Eduardo Teixeira Coelho’s A Lei da Selva (the law of the jungle; a story in which no human appears). I imagined a fac-simile edition taken directly from old O Mosquito (the mosquito) editions.

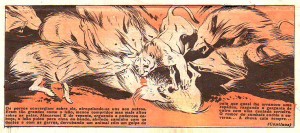

Panel from “A Lei da Selva” as published in O Mosquito # 921, April 21 1948.

It was Suat who indulged me and gave me the opportunity to be the European editor of his Rosetta # 2 (Thanks Suat! I grabbed the opportunity to choose Andrea Bruno, Edmond Baudoin, Anke Feuchtenberger, Martin tom Dieck, Max, Filipe Abranches, Jessica Khane (Isabel Carvalho) and Pedro Nora).

For Rosetta # 3 The Park by Martin Vaughn-James, a sequence of Olivier Deprez’s Le Château, and L’interview (the interview) by Guido Buzzelli would be reprinted… Ditto a translation by Matt Madden of the whole of Aristophane’s Les soeurs Zabîme (The Zabîme Sisters). (I hope that my faulty memory isn’t playing me any tricks! I remember that Edmond Baudoin’s Le portrait – the portrait – was also considered as a pièce de résistance of the issue.) Since Rosetta # 3 was never published the American public is very lucky that First Second grabbed the relay and published Aistophane’s great (and sadly last) creation.

There’s a real danger of mistaking The Zabîme Sisters for a children’s book. Someone at Publisher’s Weekly wrote (see the above link): “It’s a memorable and honest story that all young readers can enjoy.” I don’t doubt that for a second (pardon the pun): Marie Rose, Ella and Célina do what adolescent girls (Marie Rose, aka M’Rose seems a bit older) do in a summer vacation day: fooling around and enjoying themselves. But isn’t this book way above, say, Hank Ketcham’s Dennis the Menace or (even if I like its small town nostalgia and charm) Clare Briggs’ Oh Skin-nay! The Days of Real Sport?

In the frontispiece Aristophane wrote (and I quote from Matt’s translation): “This modest work is dedicated to the divine, to the oneness whose domain is everything and which can be found in each of us. A token of my devotion.” There’s no room for misinterpretations methinks: this is a religious book. I spoke many times against the colonization of the art form by children’s literature and art, but what I really abhor is, as Kupe put it above, the bowdlerization of mainstream comics. I also don’t believe that children have enough life experience to fully understand Aristophane’s (or any other really great adult comics creators’) subtleties and nuances. Sometimes the two readings are possible (e.g.: a few Carl Barks’ duck stories), but most of the time that’s not what happens: Manicheism is all over the place in the comics mainstream, as we all know…

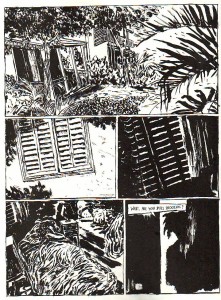

The Zabîme Sisters’ fist page.

The establishing shot above also sets the tone of the book: in its second tier the same window is shown from the outside and from the inside. We can’t hear it yet, but the narrator has a strong voice which explores the characters’ inner feelings and thoughts. This is his or her first intervention (page 4): “Célina got up after making them beg her. She took particular pleasure in being pleaded with and in feeling indispensable.” This is (and I’m following Pier Paolo Pasolini and Gilles Deleuze) the free indirect discourse that allows us to see beyond appearances.

Page 8.

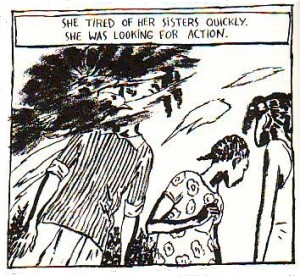

Page 28.

In the two panels above the bird and the bee may seem like senseless intrusions in the diegesis. What are they doing there? Is Aristophane just being clever or intriguing, or what?…

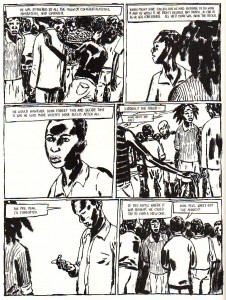

Page 33.

We just need to look at another example above to understand that: (1) Aristophane is telling us the surface of the events with what’s being said in the speech balloons; (2) exploring the inner world of the characters through the narrator’s voice over in the captions; (3) showing us something completely different and immersive with the images (it’s the free indirect discourse of the ocularization): life is all around us. That’s why his impressionistic (and fauvist) graphic style is so appropriate: we’re one with Nature, even if we can’t see it because we’re immersed in our daily petty problems. In a word, Aristophane was a Pantheist. That’s the Western religious position that approaches African Animism the most…

Even if pictures and dialogues work in two different voices, and this is sophisticated enough, what impressed me the most when I read The Zabîme Sisters for the first time was number two: how accurate and truthful the narrator is. I was so impressed at the time that, later, in another blog post, I compared Aristophane with greatness (i. e.: with Marcel Proust). Let’s see a couple of such situations:

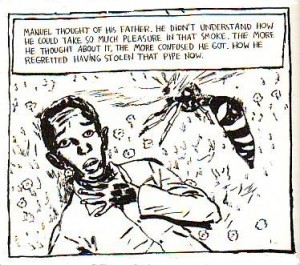

Page 74.

In the above page Manuel beat the town’s bully Vivien and his reactions are mixed: on the one hand he feels disgust because Tito now fears him (coupled with this he thinks that he did nothing but dodge Vivien’s blows; he’s also disgusted by all the pats on the shoulder); on the other hand he’s beginning to change slowly: he’s becoming arrogant. What we are witnessing is, unfortunately, a new bully in the making. Or, at least, the demonstration that praise is dangerous because we may believe in it…

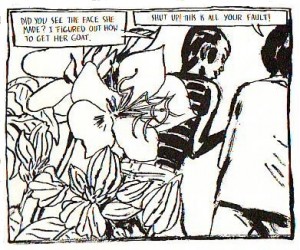

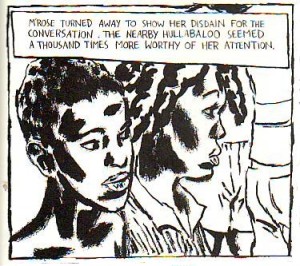

Page 51.

M’Rose is still mad with Tito because of a previous episode. Guy calls Tito to join him and M’Rose because Tito has an interesting story to tell about Vivien. I’m going to be completely subjective now (more subjective than usual, I mean): I found M’Rose’s simple gesture of turning her head away from Tito, feigning disinterest, a very nice touch. A subtle gesture that, unfortunately, we don’t see many times in the blunt world of the comics…

A final word to Nicholas Breutzman’s lettering: it’s a fine job, but Aristophane’s letters are more irregular, more lifelike, more like his brush work: they stumble a lot more on each other… And Collen AF Venable’s design: I don’t hate it or anything, but her font choice, Escrita-Principal, coupled with the Caslon type reminds me of 18th century’s Europe, which is all wrong for this story, of course. I also prefer the quiet dignity of Ego Comme X’s original design to First Second’s louder cover.

To Matt Madden: no, thank you!…

“I also don’t believe that children have enough life experience to fully understand Aristophane’s (or any other really great adult comics creators’) subtleties and nuances.”

It’s interesting that you point to life experiences in particular. Many children, after all, have life experiences that I don’t. And adults vary in life experiences; does the person with the most varied life experiences automatically get the most out of art?

Children are often not interested, or differently interested, in things than adults. But I’m not sure that maps easily onto having fewer life experiences….

Children’s fewer life experiences seems self-evident to me, so I’m not going to even discuss that (I’m not going to discuss how the Peter Pan syndrome pandemy affects the arts either). What I can say is that trying to teach great art to children is a waste of time. They will get bored and will not understand half of it. That’s exactly the mistake that’s been committed in countless class rooms all over the world. Some people hate the classics so much after the trauma that there should be a name for that particular syndrome. I don’t know what happens in other countries, but in Portugal the classics are being replaced by easier texts or by texts that are closer to the students’ daily life. Part of me sees that as just another proof of the dumbing down, another part of me perfectly understands this change in the syllabi.

Well, it depends on which classics, obviously. C.S. Lewis and Alice in Wonderland are for kids; so is a lot of Mark Twain and Kipling. And I read Dickens with enjoyment when I was 8.

I think actually (as Shaw said) art is the only way to get anyone to learn anything. I think the use of boring textbooks is far more likely to put kids off than the effort to have them read actual works of art….

Hah, Shaw once rejected an offer to include his work in a school textbook with the remark that his writings weren’t meant to be used as “torture instruments’.

Noah:

No such classics exist around here. The true classics are Luís de Camões (16th century; a huge monster of Shakesperean proportions), Father António Vieira (who defended Brazilian Indians from Portuguese colonial predators: 17th century) and Fernando Pessoa (early 20th century). The founder of Portuguese theatre, Gil Vicente (16th century) is a bit playful and maybe that’s why he’s still taught.

But your list, fine as it is, isn’t the whole story. If you want to teach the classics sooner or later you’ll have to deal with adult relationships, war, disease, politics, death. These are hardly topics that interest children (not to mention, as I said earlier, that they didn’t experience them: they weren’t exploited in their jobs, they didn’t get a divorce, they didn’t experience war or the death of someone close to them).

It’s very hard to explain to a child why this is the best painting of the 21th century: http://tinyurl.com/34t8ntj

Alex: Shaw was a very wise man!…

Domingos, I thought this was the best painting of the 20th century, but now think that I was reading you wrong, or..?

Sorry, the link disappeared. Here it is.

And now something else happened… ahem. Well, here you go:

http://thecribsheet-isabelinho.blogspot.com/2008/12/francis-bacons-triptych-may-june-1973.html

I wrote 21th, not 20th…

“It’s very hard to explain to a child why this is the best painting of the 21th century: http://tinyurl.com/34t8ntj”

Could you explain it to me? I’m curious.

The best painting of the 20th century is “A quatre mains”, by Jacques Villon. Unfortunately, it seems not to be online. But you can get a glimpse of his harmonious beauty by following the links in this:

http://www.artcyclopedia.com/artists/villon_jacques.html

BTW, Artcyclopedia is a hell of a great database.

And, no, Domingos, it is not hard to explain subtle art to a child; not at all. I know this from my experience a) as a child, and b) as a teacher.

It’s probably harder to explain it to the average adult, who tends to be calcified in his responses.

Domingos, I haven’t gotten a divorce, my exploitation in my jobs has been pretty low key, I haven’t experienced war. Many kids, though, have experienced all those things (parents divorce, exploitation, war, death of loved ones.)

And I think a child might or might not like that painting. I’d presume it would depend on the kid.

There are some things children won’t understand (though by the time you’re 12 or something, all bets are really off.) But there’s a lot of individual variation. I don’t think it’s a good idea to presume what life experiences people have and haven’t had. And I don’t think one needs to have had particular life experiences to appreciate art.

Noah:

If we think about the so-called third world, sure… It’s not likely that they will listen to one of Beethoven’s last quartets, but they surely can enjoy great art created in the context of their own culture…

Besides, you’re right if you say that these are generalizations. If I say “children” I’m saying “most children.” If we want to be even more restrictive I will add that when I say “children” I mean “most children in the Western world.” It’s not that I have done any research or anything… I just know how much crap most children consume and how they abhor great art…

Derik:

I will let Hector Obalk do the job for me (in French, unfortunately): “Eh oui… ce tableau est par ailleurs celui d’un splendide nu – comme tant d’autres dont nous n’avions étudié que la complexion du visage, nus plus étonnants et renversants les uns que les autres d’un artiste aussi grand portraitiste qu’il est peintre de nus […]. Et maintenant, pour finir, passons en revue la séquence des autoportraits du peintre à 21 ans, 31 ans, 40 ans, 44 ans, 58 ans, 62 ans, apogée de sa carrière, le regard souverain bien planté sur ses épaules d’empereur romain. Or, c’est justement dans l’intervalle historique qui sépare cet autoportrait de celui-lá, que Freud remet en question son métier, courant tous ses risques dont nous avons constaté les surprises, mais aussi les écueils. On comprend alors mieux que cette dernière révolution ne soit pas seulement technique, mais morale, puisque Freud y assume tout d’un coup, et pour la premiere fois à l’age de 70 ans, les saisissantes laideurs de la vieillesse. Il lui en aura fallu du temps pour abandonner son afféterie, son dandysme, son arrogance dans la mélancolie ou l’ironie ne trompe personne.

Et il lui aura fallu du temps pour que sa peinture, par le choix d’une brosse dure dans les années 50 e d’un blanc d’argent dans les années 80, finisse par forcer la sincérité de ce séducteur à se montrer enfin dans toute la noirceur de son visage hagard.

Tout nu dans ses chaussons ouverts pour se protéger des échardes, tout seul dans son atelier qu’il n’a jamais voulu aménager, sa palette de couleurs dans une main et son couteau à peindre de l’autre, palette et couteau qu’il brandit comme les étandards dérisoires de son destin de peintre: on peut trouver ça ridicule, moi personnellement je trouve ça sublime.”

By the way: reference: http://tinyurl.com/259koov

“I just know how much crap most children consume and how they abhor great art…”

But that’s true of adults too!

Of course, Noah. Why do you think that I mentioned the Peter Pan syndrome in the first place?…

I love that Freud painting, which I had never seen. It made me CACKLE. I don’t know why Domingos thinks it’s the best painting of the 21st century, but I was awfully pleased by its allusiveness — to Van Gogh, to grandfather Sigmund, to Jameson’s use of Van Gogh to articulate a Freudian theory of postmodern realism, to the idea of History — family history, history of painting, the life history of an old man, and History as a concept — as the constitutive material trace.

It was like he painted it JUST FOR ME. Therefore it’s of course the best!

It’s probably obvious that I think what I like about it would be kind of hard to explain to anybody, child or otherwise. (And maybe is entirely different from what Domingos likes.)

Caro:

“history of painting, the life history of an old man” is enough for me. I would love to see all of Rembrandt’s self-portraits and all of Freud’s self-portraits in one exhibition.

Besides, I don’t follow the arts at all, so, that alone is enough to devalue my opinion, but, from what I gather, is it that difficult to be the best painting of the last 9 years?

No, painting isn’t exactly the most interesting art form at the moment, although the boom years saw a prodigious rise in production, so there’s *a lot* of mediocre work out there.

Freud is definitely one of the elder statesmen by this point and he’s pretty great, but his shortcomings would become painfully clear in a show pairing him with Rembrandt. Too reliant on grotesque and too invested in a persona that he also extends to other sitters. Plus he bit his entire style from Stanley Spencer.

Well, Rembrandt was pretty much a Caravaggista… What I would find interesting in a show comparing Rembrandt’s and Freud’s self-portraits is the regularity (as Obalk put it: “à 21 ans, 31 ans, 40 ans, 44 ans, 58 ans, 62 ans […], 70 ans”) and the similar tone: from young and confident to old and half crazy…

Domingos: Interesting commentary by that author, but I’m not sure it makes a case why that’s the best painting of the century (even if that’s just 10 years of time.

Not that I have any better candidates off the top of my head. Though I can think of paintings I’d rather look at that that one.

I don’t see why a bright 10-year-old could’nt get what Obalk was saying about that painting, if he discusses it with a sensitive teacher.

And most of the cultural crap adults consume has nothing to do with ‘Peter Pan Syndrome’. Porn, anyone?

Derik:

Brian Eno once said that at the core of a great perfume there’s always a stench. I don’t believe that we can define great art or anything else with some degree of complexity, but that works as a good definition of great art to me.

Anyway, no one can convince anyone of anything, so…

Alex:

Let’s say that your 10 year old exists. Fine, that’s one… Even so I’m skeptical of a 10 year old’s true grasp of old age and decay…

If a compulsive consumer of porn isn’t afflicted with Peter Pan syndrome I don’t know who is…

Well, the key word there is ‘compulsive’; that’s begging the question. Porn in itself is an adult phenomenon.

Since you speak of Peter Pan Syndrome, I accuse you in return of Paul of Tarsus Syndrome:

“When I was a child, I spake as a child, I understood as a child, I thought as a child: but when I became a man, I put away childish things.”

— 1 Corinthians 13:11

Thereby junking the validity of the child mind…this in spite of Jesus’ teaching:

(Matthew 18:1-5.10.12-14):

At that time the disciples came to Jesus and asked him, «Who is the greatest in the kingdom of heaven?». Then Jesus called a little child, set the child in the midst of the disciples, and said, «I assure you that unless you change and become like little children, you cannot enter the kingdom of heaven. Whoever becomes lowly like this child is the greatest in the kingdom of heaven, and whoever receives such a child in my name receives me. See that you do not despise any of these little ones, for I tell you: their angels in heaven continually see the face of my heavenly Father.”

Verily, this justifies my reading ‘Uncanny X-men’, yea! Even unto # 539.

Nothing can justify reading Uncanny X-Men. Even Jesus would have balked at that.

then…I’m headed for Hell? Where Belasco and Ilyana reign?

Alex- That might be the funniest comment I’ve ever read.

I agree that it is funny, but is the humor really intended?…

There is no humor in hell.

Just to be clear: I meant # 25, not # 27, but who cares at this point, right? When silliness creeps its head it’s time to call it a day…

>>>Just to be clear: I meant # 25, not # 27>>>

Me too!

>>>When silliness creeps its head it’s time to call it a day…>>>

And also me… :)