Mat Brinkman’s Depressed Pit Dwellers and Heads, 44

Presumably you don’t need to be told Fort Thunder’s story all over again. That’s why I won’t be doing it at this time… You’re welcome!… I’ll add only this: those RISD students were multimedia artists drawn to many art forms: from music to comics, from assemblage to knitting. That’s why Mat Brinkman had one foot in the printing world and the other one in the art gallery milieu. He chose both, but don’t expect to find his work in the direct market venues. Most likely it’s not in there…

Instead of Fort Thunder’s story I’m going to tell you why the art form of comics needed the expression “graphic novels” (like that: in the plural form) and how it became part of our current language (you know all this already too, but I insist on my narrative because it isn’t stressed enough when people discuss what’s a graphic novel)… Chris Oliveros, the publisher of Drawn & Quarterly (ditto other alternative comics publishers, I’m sure), knew that, in order to sell his books, he needed to find alternatives to the superhero dominated direct market (in other words, he needed to flee the comics ghetto). He needed to sell in regular bookstores, but, in there, his books were lumped in with superhero comics collections and newspaper reprints. He needed to convince the BISAC to create a new label to be used in bookstores: “Graphic Novels”. This category would consist of “extended-length illustrated books with mature literary themes”, as Matthew Shaer put it in the link above. I don’t know if, a few years later, even after the creation of said category, Chris Oliveros was completely successful. According to Eddie Campbell (the creator of the hilarious Graphic Novel Manifesto): “the librarians and to some extent the book trade have decided that the graphic novel is a young readers’ genre. […] [H]ere is the sequence of events: circa 1980 [after the impact of Will Eisner’s A Contract with God and Other Tenement Stories] it was decided that comics had grown up and the grown-up version would be called ‘the graphic novel.’ [An expression coined by Richard Kyle in 1964, but with earlier uses in other languages; as all concepts its meaning changed over the years though.] This has been forgotten and […] we’re right back where we started.”

Frankly it’s not my aim to discuss the graphic novel phenomenon. To me it’s just a marketing device that I applaud because it helps to find new readers to the comics that I champion the most. Apart from that I understand Eddie Campbell when he said that the graphic novel is not a format (it’s a genre, to echo the “it’s not a genre, it’s a medium” mantra, usually applied to comics; Eddie could be absolutely right if we think that a comic book is not always comical and it certainly isn’t a book), but many different things have been called graphic novels: from a collection of short stories (Will Eisner’s A Contract With God and Other Tenement Stories) to autobiography and biography at the same time (Maus by Art Spiegelman) to journalism (Joe Sacco’s Palestine). That’s why I say that a graphic novel is a format that pretty much stands for “trade paperback” and “prestige format” in the public’s mind. That’s also why the direct market easily co-opted the expression:

Forbidden Planet, London, UK.

Anyway, bookstores are just one of the possible alternatives to escape the comics ghetto. Another alternative is the art gallery. Art galleries publish art catalogues and artists’ books. They’re, therefore, also publishers…

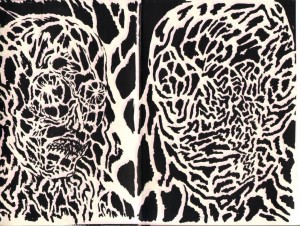

In Mat Brinkman’s Heads, 44′s print run of 1000 boutique comics publisher Picturebox and The Hole art gallery joined efforts. According to the book’s back cover Brinkman exhibited his monster heads in Mail Order Monsters at Max Wigram gallery in London (UK). I can’t resist reproducing part of the gallery’s press release:

Tapping into an underground music and graffiti vibe the selection of works in the show also finds reference in computer-programme aesthetics. Taking its title from a 1980s videogame (which allowed you to build your own monster) the show suggests an approach to the figuration in contemporary art practice which brings together fictional fantasy with the post-human figure of techno-dystopia, depicting the body as broken, decaying, uncanny and monstrous.

Brinkman’s monster heads were also exhibited in New York Minute: 60 Artisti della scena newyorchese at the Macro Museum in Rome, Italy (see also this view of the exhibition: seconda sala – second room, fourth dot), Melissa Brown and Mat Brinkman at M & B gallery, Los Angeles, among other places like Berlin (Germany) and Athens (Greece).

Before Heads, 44 there were the Depressed Pit Dwellers, a book published in 2008 by art brut French publishers Le Dernier Cri who titled it simply Monsters on their website. Depressed Pit Dwellers is an eleven colors silk screen book with a print run of 200.

Double-page spread in Depressed Pit Dwellers showing Mat’s unorthodox use of the silk-screen.

As we can easily imagine from the print run numbers above we’re far from comics as a mass medium, but, on the other hand, we must add the number of gallery and museum goers who saw Mat Brinkman’s drawings. I have no idea which numbers we’re talking about though…

In the pre-history of these two books are Mat Brinkman’s comics published mainly in mini-comics and the newspaper Paper Rodeo. All collected in two books: Teratoid Heights (Highwater Books, 2003) and Multiforce (Picturebox, 2009).

In another post I said:

What’s Fort Thunder, really? If I had to define it with one word it would be: noise. It gave the name to the artists’ group and noise-rock was played there. But is there such a thing as visual noise? Yes, there is: in information theory (Shannon-Weaver model) noise is everything that distorts the transmission of information. (Instead of simply saying “noise” I should have used the more accurate expression “semantic noise,” though.) This means that Fort Thunder is some sort of Dada (Kurt Schwitters’ Merzbau is the grandfather of the Fort), Funk (Jim Nutt et al – I personally have a soft spot for Roy de Forest and Nicholas Africano), Punk (Gary Panter comes to mind), aesthetic. Not to mention Art Brut, New Image, Figuration Libre, etc… etc…

Nothing new under the sun? It depends: no one cited above invested in comics as the Fort Thunder artists did (except Panter, of course); they brought their generations’ imagery (the eighties’ video games and other cultural detritus) to the forefront.

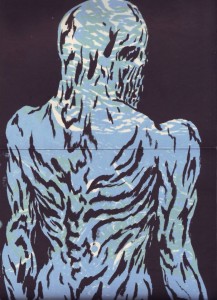

In Depressed Pit Dwellers the reader/viewer can find a new visual device in Mat Brinkman’s work: since silk-screen is a gradual process of adding layer upon layer of colors it’s obvious that Mat Brinkman would, trying the technique in a funky way, loose unity and accordance (to gain entropy). The monsters, and everything around them, drawn in black, are transparent beings showing their brightly colored innards.

Single page from Depressed Pit Dwellers.

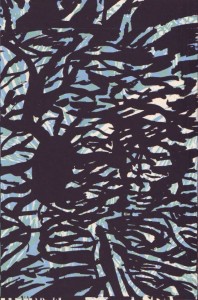

Other times, as we can see above, the “degradation” comes to its paroxysm and reaches a kind of abstaction.

Another Double-page spread in Depressed Pit Dwellers.

In the image above the process used in Heads, 44 can be detected already. Here’s how The Hole’s press release describes it:

As Mat drew, each of these ink-on-rice paper “heads” would seep onto the next sheet, forming the basis of that drawing, and so on. We’ve reproduced this work by printing on fine vellum with extra dense black ink which was quick-dried with UV lamps. Watch as marks coalesce, animate, and come alive.

As Ao Meng put in his great review:

In this way an organic, wordless narrative emerges. Some of the heads are chillingly detailed, while others explode into almost pure Rorschach-blot abstraction. Some of the images are so obscure that as individual works they would be difficult to identify as faces. However, the magic of “Heads, 44“ as a comic of sequenced art versus a collection of related works is that the physical transparency of the paper allows the viewer to see the next image underneath the current page. The viewer is always between pages, experiencing multiple images at once.

To the question: can Mat Brinkman reproduce the same transparency effect that he used in Depressed Pit Dwellers using black ink only? The answer is: yes he can. As we turn the vellum pages two additional tones of gray appear creating textures with the thick black ink (two pages later the black is light gray, one page later it’s dark gray). This is a Darwinian process of gradual mutation that begins with the monster and ends in nothingness… Info theory entropy joining bio entropy: loose blotty cells that have barely a reason to stay together…

Heads, 44′s last page.

Pingback: Tweets that mention Very nice Domingos Isabelinho piece on art gallery comics and Mat Brinkman's Depressed Pit Dwellers & Heads, 44: -- Topsy.com

Oi, you!

How come you’ve taken care to put everything in the past tense except “Eddie Campbell says” when you are referring to something that Eddie Campbell said several years ago? Eddie Campbell’s current views may be quite different, though I’m sure they would still be quite different from your own.

merry Christmas!

Thanks! I wish you a great 2011! I know that things look bleak enough from where I stand…

Several years? Here’s what’s at the top of your post, Eddie: “Saturday, 1 August 2009.” Anyway… Even if you think the opposite my mission in this world is not to upset you, that’s why I updated my post to be in accordance with your desires.

I offer 150 euro for a copy of monster book by Mat Brinkman