Originally presented: Panel on Frames and Ways of Seeing in Modernist Narrative at The Tenth Annual Modernist Studies Association (MSA) Conference, Nashville, TN, November 2008.

Author’s introduction (“disclaimer”)

This paper was presented at the Modernist Studies Association conference two years ago. As such, the audience for the talk was not comics scholars, or, even, necessarily people who were interesed in comics. The paper is pitched to that audience and therefore says quite a number of things about comics that are fairly obvious to the comics scholar (or even just the perceptive comics reader). In fact, it even says things I know to be debatable, and even incorrect, since those things weren’t my primary concern. So, yes, I know that “The Yellow Kid” isn’t the first comic strip in U.S. newspapers (to say nothing of the world at large), but since splitting those hairs wasn’t the point of the paper, I used that as a generally “known” reference point.

I was invited to participate in a panel on “frames and ways of seeing in modernist narrative” after one of the participants in the original panel dropped out. As I recall, all three of the original panelists were from the University of Toronto, studying under/with noted modernist scholar, Melba Cuddy-Keane. Cuddy-Keane got in touch with my dissertation advisor at University of Maryland, Brian Richardson, and asked if he knew anyone interested in frame narration and modernism. Brian got in touch with me, recalling a paper I had written for him many years previous as a graduate student. That paper, however, was already forthcoming in Narrative, and I wasn’t really interested in recycling the material. So, I took the opportunity to apply some of the research I was doing on time, modernism, and comics and to write some of that out, rather than merely having it bounce around in my head. All of this is the long way of saying that the paper was even more rushed and “tossed off” than the typical conference paper, since I was a late addition to the program. At this point, I feel as if there may be nothing particularly revelatory here, as much of this material feels (to me, anyway) as if it’s fairly obvious and straightforward and covered elsewhere in the literature. Since this is a blog (my brother’s no less), I don’t feel quite so guilty about letting it see the light of day, as long as nobody really feels like it reflects the care I generally take in my scholarship. Things that make me cringe a bit, are… a) sources cited, but no bibliography listed. The sources are mentioned, for the most part, in the paper itself, but obviously, a bibliography should be included. Since I was only reading it out loud at the time, however, and I knew the sources, I never typed them up. (At this point, this note may be taking longer than it would take to type the sources… but let’s not ruin a fairly boring and mediocre story). 2) The paper also includes various notes to myself telling me to elaborate on this point or that orally. Obviously, for written publication, I should turn those into more coherent written claims… but I’m just writing a disclaimer instead. [Many of these were references to the images, so I’ve replaced them with “See Fig. X” reference. -ed.] 3) The quality of the scans is sometimes pretty bad, as well. My scanner is just an 8 x 11 and some of my sources were much bigger. I should have gone to the Artist Formerly Known as Kinko’s and done the scans on a larger printer to get things right… but, again, I reveal the generally slipshod nature of my efforts on this particular piece. All of this is why I told Noah and Derik that they could have this conference paper if they wanted it… but that I was generally unsure of its “ready for prime time” (using the term loosely) status. Derik and Noah decided to run it anyway (making me think that they reall need more submissions for this feature [We do! Send us something -ed.]), so, here it is “warts and all.”

“Through Space, Through Time:” Four Dimensional Perspective and the Comics by Eric Berlatsky

Whether pamphlet-form comic books, cramped newspaper comic strips, or more traditionally codex-form “graphic novels,” comics have only recently started to receive serious critical attention as “art objects,” as opposed to mass culture ephemera. The biggest breakthrough in comics criticism is still undoubtedly Scott McCloud’s 1993 book Understanding Comics, a book that makes a bold play for considering comics as “art,” by bypassing the typical starting date for its history. The standard date, particularly in America, is, of course, 1895, marking the beginning of R. F. Outcault’s Hogan’s Alley as a newspaper comics page in The New York World. This date, would, of course, place the origins of the newspaper comic strip in close chronological proximity to the “high art” development of modernism. However, McCloud’s choice to define comics as “sequential art,” or, in the longer version, “juxtaposed pictorial and other images in deliberate sequence,” allows him to include pre-Columbian picture manuscripts, the Bayeux tapestry, Egyptian painting, Trajan’s column, and Hogarth’s “Harlot’s Progress” as comics, along with other, more likely, suspects, like Rodolphe Topfer’s “picture stories” of the mid-nineteenth century (McCloud 10-17). McCloud discards some of the elements of earlier definitions of comics in order to detach the era of comics’ increasing popularity (the twentieth century) from its definition, suggesting that some of the greatest achievements of older “high art” are, in fact, comics. While this has the potential to raise the culture caché of comics as a medium, it also obscures the ways in which the form reflects and takes part in the modernist project and the advent of modernity.

David Kunzle, by contrast, argues that in order for something to be considered “comics,” it must be intended for reproduction, linking comics to the history of mass printing, as in the daily newspaper where comics gained its popular foothold in contemporary culture (History of the Comic Strip v.1, 1973). While Kunzle’s claim is problematic in other ways, it succeeds in fastening comics to the high-speed modernity of the turn into the twentieth-century, a time marked, perhaps most forcefully, by speed and simultaneity, as Stephen Kern emphasized in his The Culture of Time and Space 25 years ago. Telegraphs, telephones, high-speed trains, the automobile, the airplane, and cinema all made it possible for widely disparate places to undergo the same experiences simultaneously, or to at least give the appearance of simultaneity. Comic strips, like the rest of the newspaper, were experienced simultaneously by thousands of readers in stark contrast with the Bayeux tapestry, which could be experienced by only a small number of people at once, and never from precisely the same perspective. Relative to the newspaper, thousands of pairs of eyes could occupy the same space at the same time, while relative to the Tapestry, only one pair of eyes at a time could occupy one space.

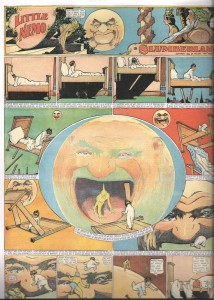

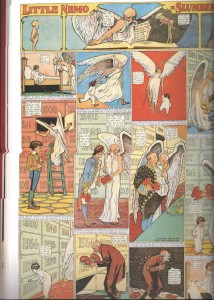

Fig. 1 – Winsor McCay’s Little Nemo in Slumberland from 1905

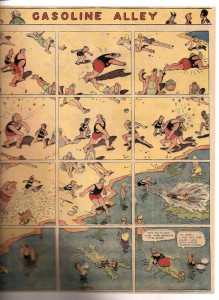

Simultaneity is important not only to the reception of comics, however, but also to the form itself, something which McCloud’s focus on sequence obscures. McCloud mentions how comics must be multiple images “juxtaposed,” but he does not insist that these juxtaposed images must be able to be viewed simultaneously. This is, however, perhaps the most unique quality of early newspaper comic strips, especially Sunday pages, which could, by their nature, be viewed both sequentially and simultaneously. That is, in the early days of newspaper comics, it was possible to open to a Sunday page and see that entire page as a single design, with panels arranged as compositional elements of a larger “picture” or “painting” (see Fig. 1, 2, 3). In most cases, of course, the strip could also be read sequentially, as we see Walt and Skeezix (Fig. 2) moving sequentially across a still background, showing us both a variety of discrete spaces at the same time, and a variety of different times articulated as space.

Fig. 2 – Frank King’s Gasoline Alley from August 30, 1930

Fig. 3 – Swamp Thing from [unknown].

In fact, McCloud is quick to note how the comics format gives the artist unique opportunities to use the “page space,” indicating how the Bayeux tapestry might be read as a “whole page composition” in the manner of McCay or King, and how comics artists use this inherent feature of the medium far too infrequently (12). At the same time, McCloud’s use of “whole page” is somewhat disingenuous if applied to Trajan’s column or the Bayeux tapestry. These objects are simply too big, or too oddly-shaped to actually be viewed simultaneously, as a whole, in one instant. To see all of the Bayeux tapestry, one would have to stand too far away to be able to make out the contents of the picture, while only a segment of Trajan’s column can be seen at a time without having to walk around the column, bringing the progression of time, or sequentiality into the picture. The newspaper comics page provided an ideal instrument for witnessing an entire composition simultaneously, without making it impossible to also see the sequential progression of panels. It was the paradoxical capacity of the comics page to be seen both as a single instant and as a sequence of instants, that created “modern” comics, and it was the much neglected unit of the single page “story” that made such a union possible. In this way, newspaper comics were different from the (typically older) high art with which McCloud wishes to join them, an important distinction given the significance of simultaneity to modern existence. Single paintings or sculptures are usually seen as, or in, a single instant in time, but they do not also depict sequence. McCloud’s early examples of proto-comics, by contrast, tend to sacrifice simultaneity for sequentiality.

As McCloud notes as well, film is a medium that operates in time, with images flowing past at the rate of 24 per second. That is, what one sees on the cinema screen is a series of sequential images, many images that give the illusion of time flowing irrevocably forward, as it seems to do for us in “real life.” While a stoppage of the film (or the repetition of the same image) can give the illusion of a single instant, this simultaneity does not coexist with a sense of sequentiality. Instead, it usually exchanges one for the other. Likewise, as Kern points out, a variety of filmic techniques, like double exposure, montage balloons, and parallel editing, were used to suggest simultaneity in film’s early days, but the film nevertheless always rolled by in time. In film, we are inevitably given sequence, with simultaneity approximated with a variety of techniques. In comics, simultaneity is inherent to the form.

Fig. 4 – “First Simultaneous Book” image from Kern 73

My account of simultaneity thus far depends on a fairly common-sense use of the term: Different “things” in different “places” happening at the “same time.” As Kern notes, the introduction of the telegraph and telephone near the close of the nineteenth century made the world seem much smaller and made it seem possible to be “in two places at once,” both in your own home, on your own phone, and, perhaps, halfway across the city, or the world, where your voice ended up. The Futurist fascination with simultaneity was, of course, spawned by this new hyper-industrial understanding of time and space, creating works like Blaise Cendrars’ “First Simultaneous Book,” which included both image and text (see Fig. 4), including an illustration by Sonia Selaunay, a map of the Trans-Siberian railway, and a poem about Cendrars’ journey on it. The insistence on a single page, so as to approximate simultaneity and to reduce the “sequential” effect of turning pages, along with the combination of image and text, makes Cendrars’ 1913 breakthrough seem like nothing so much as an American Sunday comics page, without the funny animals or gags. The use of rectangular “panels,” to separate title, painting, map, and poem might even give the reader a clue on how to read the “book” sequentially, despite its attempt to approximate simultaneity.

Fig. 5 – George Herriman’s Krazy Kat from February 5, 1922

As Kern notes, the subject matter and map of the train journey encapsulates Cendrars’ efforts to connect different spaces at the same instant, since the map shows widely disparate places at the same time, even more quickly than the high speed train could actually join them. Similar techniques were used in contemporary comics like George Herriman’s Krazy Kat, which uses the panel to show two separate locations in a single panel, indicating that the actions in them take place at the same time. The train is always a signifier of the advent of modernity, of course, and its high-speed crisscrossing of this page (see Fig. 5) shows the near instantaneous journey of the train from one place to another as in Cendrars’ “book.” As Kern says of the “Simultaneous Book” however, Cendrars is not merely interested in showing multiple places simultaneously, but also, and paradoxically, multiple times. The poem is designed to express Cendrars’ capacity to “experience every moment of the journey and the world beyond it simultaneously” (74). How can multiple times be shown simultaneously, or at the same time? The cubists attempted this by showing multiple perspectives on the same person or object in a single picture, thus indicating either multiple times and/or multiple spatial orientations at one moment. Cendrars did so with “verbal montages,” juxtaposing multiple far-flung locales in near-simultaneous time, and with fanciful autobiographical visions that, as Kern notes “unit[e] remote ages.” “I spent my childhood in the hanging gardens of Babylon” (qtd. in Kern 74), Cendrars unrealistically declares.

The fascination with showing not only multiple spaces at once (simultaneously), but also, and paradoxically, many times, coincides with, and is perhaps partially inspired by, the emergence of Einstein’s Special Theory of Relativity in 1905. With this theory, Einstein, of course, introduced the shocking notion that time is not “homogeneous” and “empty” as Newton asserted more than 200 years earlier. Rather, time actually passes more slowly or more quickly based on the speed at which an object moves (especially as it approaches the speed of light) and by its rate of acceleration. The relatively new notion that diverse spaces could be joined at the same time (through telephone or telegraph or radio waves) was almost immediately undercut by Einstein’s theory which indicates that no two places could ever share a single time, both because it takes time (however brief) for sound and light to travel through the new technology, and because time is actually moving at different speeds in different places, depending on such variable phenomena as rate of motion and altitude.

While, no doubt, early comics creators were largely ignorant of the mathematical basis or “real-world” ramifications of these findings, the comics page nevertheless expresses a strikingly similar sense of time, which later creators were quick to link to ideas of Einstein’s relativity. A return to the Krazy Kat page, for instance, combines its single panel expression of spatial simultaneity with a full page expression of temporal simultaneity: multiple different times capable of being viewed at once.

Fig. 6 – Winsor McCay’s Little Nemo in Slumberland from December 31, 1905

This Little Nemo page (see Fig. 6), published at the close of 1905, the same year as the Special Theory, is even more indicative of Einsteinian thought, since each panel shows Nemo at a different age, scrolling through a wall of dates and aging (or occasionally getting younger) in an instant. Time passes at a different rate, however, for the Father Time figure, who remains old and bearded throughout. For Father Time, then, the panels progress sequentially, progressively, and at roughly the same rate from panel to panel, while Nemo’s time accelerates, or reverses, rapidly depending on which date he takes off the wall. For Nemo, of course, this is all just a dream, and is in no way meant to reflect the very recent advances in theoretical physics. Nevertheless, the idea of time passing at different rates for different individuals parallels Einstein’s famous “Ann and Betty” thought experiment, where Betty travels in a rocket ship at 80% of the speed of light away from and back to Earth, while Ann stays on Earth. While twenty years pass for Ann, Betty’s rapid speed actually slows time for her and her ship, and she only ages 12. That is, if Betty leaves earth in 1905 and returns in 1925, twenty years have passed on Earth, but only 12 have passed in the rocket ship, simply because of Betty’s speed of travel. In different places, time is passing at different rates, making the notion of “simultaneous” spaces meaningless, although a paradoxical notion of simultaneous times is introduced. As Einstein points out, if there is no “present” which multiple spaces can share, then the terms past and future can also have no universal meaning. One person’s “present” is another’s past, or future, suggesting that, in a sense, all times are simultaneous, something the typical comics page also indicates, since each panel is usually a different “time,” but is capable of being viewed simultaneously.

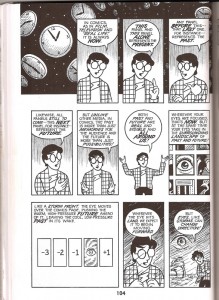

Fig. 7 – Scott McCloud’s Understanding Comics p.104

Indeed, Einstein’s shift to his “General Theory” of relativity in 1915 makes the connection to comics even clearer. With the realization that gravitation and acceleration were not only related but equivalent, Einstein, with the help of Hermann Minkowski, insisted that time and space were actually connected physically, and could be graphed spatially as a fourth dimension. As theoretical physicist Paul Davies notes, “Minkowski insisted that he was not […] tacking an extra time dimension onto the three space dimensions for fun, but because the resulting entity formed a unified ‘spacetime continuum,’ in which the purely spatial and the purely temporal aspects could no longer be untangled” (73). The notion that time is merely a fourth dimension that we experience, but do not see, indicates that past, present, and future are, in some sense, places that we go, and that they are all always already there, in accordance with the Special Theory’s erasure of universal notions of before, then, and now. In many ways, the comics page too is a four-dimensional-graph, in which past, present, and future are always already there, since we can progress through them sequentially, or take a new perspective and view them all at once. This is why McCloud argues (see Fig. 7), with no mention of Einstein, that, “In learning to read comics we all learned to perceive time spatially, for in the world of comics, time and space are one and the same” (100). Time is turned into space on the comics page, just as it is in Minkowski’s four-dimensional spacetime graphs.

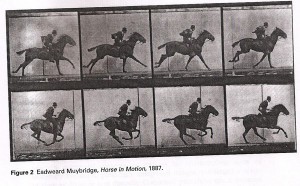

Fig. 8 – Edward Muybridge, “Horse in Motion”, 1887

What makes comics particularly “modernist,” though, in ways few have acknowledged, is their capacity to represent two perspectives (or two “frames” of reference) at once. Michael Leja, in Looking Askance, has suggested how modernist art introduces a kind of skepticism toward vision, wherein seeing is no longer believing, and there is an intensified disbelief in “common-sense” notions of a reality defined by vision. The “common-sense” notion of time, at least since Newton, has been of a passage of time that is regular, consistent, and sequential. While Bergson insists on a more internal subjective time that varies from individual to individual, even he never rejects the “reality” of an alternative social time shared by humans, who define it by clocks. As Scott Bukataman has noted, an intensified interest in the sequential moments of time was a primary feature of Edward Muybridge’s chronophotography, developing at the end of the 19th century, and this interest was not, in fact, alien to comics, but central to it. As Bukataman shows, McCay’s Sammy Sneeze and (again) Little Nemo are obsessed with a regular, almost “ticking” clock time, that records motion in regular intervals (see Figs. 8, 9) indicating a belief, even a faith, in Newton’s homogeneous empty time. At the same time, however, this page intrinsically gives us an alternative view, of past, present, and future mapped spatially and coexisting simultaneously, merely with a reorientation of vision. Whether intentional or not (and likely not), McCay’s page shows us both Newtonian and Einsteinian time, two visions of time that seem to work together easily both on the page and in reality, unless one happens to be under extreme gravitation or traveling at high speed.

Fig. 9 – Winsor McCay’s Little Nemo in Slumberland from 1905

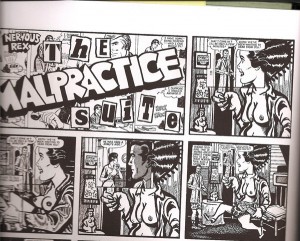

It has taken some time for comics creators to identify their medium’s own affiliation with the modernism that developed contemporaneously with it, but creators like Art Spiegelman insist on comics’ affiliation with modernist high art, precisely because of its capacity to present two visions of reality simultaneously, as in cubism. In this page from “The Malpractice Suite,” (1972) (see Fig. 10) Spiegelman indicates how the view of the panel from the “Rex Morgan, M. D.” newspaper strip may seem “real,” but actually provides only a partial perspective, similar to cubism’s rejection of simple vanishing lines and singular perspectives. The real revelation here should not, however, be how comics can imitate the formal innovation of cubism, but how it always necessarily must, since the panel and the page are always two aesthetic units that provide alternative and differing perspectives of sequential and simultaneous time.

Fig. 10 – Art Speigelman’s “Malpractice Suite” from Breakdowns

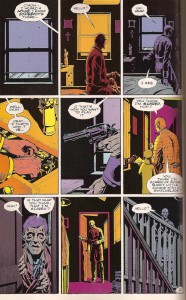

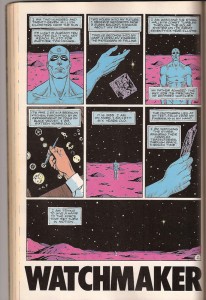

Fig. 11 – Sequentiality in Alan Moore and Dave Gibbon’s Watchman, Chapter 5 p.2

Fig. 12 – Simultaneity in Alan Moore and Dave Gibbon’s Watchman, Chapter 4 p.2

The contemporary creator perhaps most devoted to exploring the relationship between the development of relativity theory and comics is Alan Moore, who, in 1986-1987’s Watchmen, provides us with a text both obsessed with sequential clock time (as a doomsday clock ticks down toward nuclear war), and with Einsteinian simultaneity, particularly in its depiction of a “superhero” ex-physicist who experiences time spatially and simultaneously (see Figs. 11-12). Likewise, in From Hell, Moore takes these ideas back to the 1880s, just before the introduction of modern comics, and builds a story around the Jack the Ripper murders and C. H. Hinton’s early discussion of a fourth dimension in the 1884 essay, “What is the Fourth Dimension.” Moore’s own formal play with the dual nature of sequence and simultaneity reaches its apex, perhaps, in the final issue of Promethea (April, 2005). Here, the reader can choose to read the story sequentially, like a traditional comic, or to take the staples out and create a giant poster, or “page,” that can be read in a different order, or seen, simultaneously, as a single image (see Fig. 13). The first page of this issue has an unnamed narrator inform us that “Einstein’s Spacetime is a timeless four-dimensional solid, containing every instant simultaneously, forever… including our lives. Death, therefore, is a perspective illusion of the third dimension. Don’t worry. A funeral celebration, or wake, dominates James Joyce’s Finnegan’s Wake in which all human experience is distilled into one timeless day.” Here, Moore pulls together Einstein’s sense of time and one of the most iconic of modernist literary masterpieces. Moore’s creation of a sequential comic book that is also a simultaneous poster approximates the Wake’s circular achievement, but more than this, it reminds us of how the single comics page, emerging contemporaneously with both modernism and Einsteinian spacetime, has always done so. It is perhaps, time, to consider comics as a particularly modernist medium, not only because of the time in which it develops, but also because of its development of time.

Fig. 13 – Alan Moore and J.H. Williams III’s Promethea

Eric Berlatsky is Associate Professor of English at Florida Atlantic University in Boca Raton, Florida. He specializes in twentieth-century British and postcolonial literatures, (post)modernism, and, when he can get away with it, comic books. He has published essays in academic journals or collections on Julian Barnes’ Flaubert’s Parrot, embedded and frame narratives, Paul Auster’s New York Trilogy, Virginia Woolf’s Between the Acts, Graham Swift’s Waterland, Milan Kundera’s Book of Laughter and Forgetting and Art Spiegelman’s Maus, and Charles Dickens’ David Copperfield. He has also published online essays on Alan Moore’s League of Extraordinary Gentlemen and Swamp Thing. He is currently completing work on the editing of a collection of career-spanning interviews with Alan Moore (Alan Moore: Conversations), which will appear in Fall 2011 or Spring 2012 from the University of Mississippi Press. His first book, The Real, the True, and The Told: Postmodern Historical Narrative and the Ethics of Representation is forthcoming in April 2011 from The Ohio State University Press. It includes a lengthy chapter on Art Spiegelman’s Maus, for the comics aficianados.

The Swamp Thing is a page from #61, where Swampy lands on a planet with sentient vegetables (and a Green Lantern).

scoll dis

”

for this marquee to roll around again and get it, i’m not going to spell it out for you. cinco seis dos – ocho cinco dos – cero dos sesenta y seis ////// cae la noche dot net – don forget that!

“

Eric, I think you disclaim too much. I like the essay!

Sort of going off some of what we’re talking about in the other thread…I see your point about comics as a product of modernism, in terms of reproduction, competing viewpoints, different takes on time, etc. But doesn’t it seem like a somewhat severed bit of modernism, rather than an organic part? That is, comics may reproduce some of modernism’s concerns, but there’s little sense that modernism as it’s usually understood really noticed, is there? That’s sort of emphasized by your disclaimer and the context; you’re having to sell comics as modernism to an audience interested in modernism, whereas if comics was really *part* of modernism in the usual sense, presumably folks interested in modernism wouldn’t need to be sold.

I guess the question is, as someone interested in modernism and comics, does comics have something unique to teach modernism? Or is it more that understanding comics through modernism teaches something about comics?

Well, modernism noticed somewhat, in some avenues. I was surprised reading some early T.S. Eliot poems that there is a figure reading comics in the newspaper (on a park bench or something) in one poem. And Krazy Kat (somewhat later) was picked up as an exemplar of (or linked to) surrealism. It’s more about what we’re willing to call modernism. If we’re only talking about “high modernism” in literature, the connections are slimmer…If we’re willing to see Futurism, Vorticism, etc. etc. as part of modernism (using a broader definition–as reflections of modernity), then the connections are more easily perceived. For me, I guess, thinking about modernism reveals things about comics that one might not ordinarily perceive—but the reverse is somewhat true as well. Insofar as the mass culture vs. high culture divide is often perceived as central to ideas of modernism—the fact that one can see the same formal devices in comics as in modernist “high culture” reveals how that divide is tenuous, to say the least.

Do literary modernists really exclude the Vorticists? Even from high modernism, given the ties to Pound? And Lewis (Jameson has that early book on him…) and Eliot was published in Blast…

Just seems odd, like taking sides in Lewis’ battles with Fry. Of course, most scholars have embraced “modernisms” yes?

(This has to win the award for the most boringly academic comment/question ever. LOL.)

Well, perhaps Vorticism split into so many directions that it’s not perceived as a solid, influential force. I mean, the links between Vorticism and Imagism are there, but would one lump an imagist poet like HD with Vorticism?

There might also be politicallly- inspired neglect…again, Pound…and Wyndham Lewis’ drift to the right (he wrote a book admiring Hitler) probably served to damn him in the eyes of more left-wing academics…

“served to damn him in the eyes of more left-wing academics…”

Admiring Hitler will damn you in the eyes of even non left-wing non academics. He’s not a popular figure, Hitler.

The book Alex mentions was from ’31, and Lewis recanted it pretty thoroughly in another book in ’39 called “The Hitler Cult,” so he did backtrack on it long before the worst revelations of the war. But I’m sure it hurt his reputation. He was pretty well redeemed by the ’50s though; he was close friends with and very influential on Marshall McLuhan. I’d agree Vorticism hasn’t been perceived as a solid influence, though.

Pound was friends with (former lover of?) HD (he was sort of the Kevin Bacon of modernism) and claimed he got the idea of the Vortex from one of her poems, which he quoted in Blast. So I’d certainly associate her with the Vorticists, but I don’t know whether she admitted or embraced the connection; it might have been a one-way influence.

Yes, “modernisms” is definitely the term people have liked for awhile now. Happy to provide the boring academic answer… I would say Vorticism is definitely considered a part of literary modernism even if Lewis is often forgotten (or pushed to the background) these days…I just threw that in there after seeing Caro’s post. The tendency now (I think) is to try to think of “modernism” as a reflection of modernity–which means both mass culture and traditionally high culture modernism are part of it and the connections between them are considered more often than the differences…. (So “The Waste Land” is studied in terms of its marketing as much as for its aesthetics). Still, while there is a sense that comics are part of this material culture of modernity–there doesn’t seem to be that much work that I’ve seen that connects comics to modernism aesthetically… (although I kind of feel like that sense is out there). So…this was my effort to think that through a bit).

H.D. is, I think, most often thought of as an Imagist, because of the Pound influence.

The truth is, though, my knowledge of these figures is often pretty weak. I’m also not all that privy to “latest debates in modernism” as most of my work is really in “postmodernism.” I only went to MSA because I was invited to after someone dropped out. So, my own sense of modernism is definitely not “newest latest”—

Still, the connections to comics are definitely there and I kind of see the work of Moore, Spiegelman, and a few others as a kind of belated self-aware modernism…as opposed to the “modernism-by-accident” that you see in some of the earlier figures I cite. I see Watchmen as very much a “modernist” work in its density of figuration and semiotic self-reference. It’s like Ulysses in that everythng in there is referring to something else…and in the fact that often it’s unclear what these symbols are meant to mean. Often, self-reference is its own goal, to provide a sense of density and complexity… Of course, Moore is willing to give you a linear action mystery plot, which someone like Joyce isn’t. And obviously Spiegelman’s work in Breakdowns and Raw, etc. brings the kind of modernist sensibility to comics in a self-aware way. But I guess I said all that in the essay.

@Caro:

You’re correct about Lewis’ repudiation of Hitler; but leftists have long and unforgiving memories…in France, André Gide has suffered an eclipse of his reputation because he turned against communism when he became aware of Stalin’s monstrosities.

Complicating the picture is Lewis’ own dismissive attitude towards Vorticism in his later life, and his rather reactionary attacks on modernism and the very notion of an avant-garde.

Still, Caro, referring to your recent post– thanks for opening my eyes to the wide-ranging artistic fields of Vorticism. I had never made the connection to Epstein or to Eliot!

I may be in London when the exhibition moves there; of course, I won’t fail to attend it.

Oh, I completely agree, Alex. Fredric Jameson’s 1979 book about Lewis was titled “Fables of Aggression: Wyndham Lewis, the Modernist as Fascist.” But…that said, I heard him speak about Lewis a month or so ago and he was far more positive about his influence. So perhaps research in this area will be opening up.

Glad you enjoyed the post!

@Alex Buchet. You’re making a lot of assumptions about leftists and Lewis’ historical reputation that simply don’t hold water. It’s true that in the 1930s Lewis’ reputation suffered because he wrote a book celebrating Hitler as “a man of peace.” But there were other modernists writers and thinkers who were much more implicated than Lewis in fascism (like Pound, Ernst Junger, Heidegger) who, despite their controversial politics, continued to have many readers in the 1930s, 1940s, and 1950s. Lewis is a very interesting and at times great writer — I own many of his books — but he’s also very uneven. I think the big thing with him is that he scattered his energies too widely (he wrote novels, political and social tracts, liteary criticism and also painted). So he never really produced a single great masterpiece like Ulysses or The Wasteland. Also, he strongly condemned many fellow writers like Joyce, Woolf and Hemingway, which also hurt his reputation (in his memoirs Heminway said Lewis looked like an unsuccessful rapist. That’s gotta hurt).

The politics of Lewis criticism is more complex than you imagine. It’s true that a certain type of conservative — Hugh Kenner being the best example — tends to be pro-Lewis. But much of the best Lewis criticism is written by liberals and Leftists. As Caro mentioned, Fredric Jameson has written a splendid monograph on Lewis, by far the most influential book on Lewis. Jameson has a very high opinion of Lewis — higher than my own. And of course Jameson is a Marxist.

So I think you need to rethink your reflexive anti-leftism.

Hey Jeet. I’m pretty sure Alex isn’t anti-leftist. Maybe anti-leftist academics….?

I’m not only not anti-leftist, I’m a commie!

Seriously…Jeet’s analysis is right on, but what we were discussing was why Vorticism is relatively eclipsed in discussions of modernism.

Mind you, there may be an extremely stupid but depressingly plausible reason.

Geography. Pre-first-world-war London was not necessarily considered an important intellectual or artistic center, compared to Paris, Berlin or Vienna.

This is unfair and untrue, but certainly the image of the Briton as an Alma-Tadema worshipping Philistine was a well-established cliché– not least in Britain.

I don’t think it’s geography: Vorticism started when Lewis split off from Bloomsbury, which is insanely canonical, almost iconically canonical, and London-based…

I do think it’s politics — complicated politics — but not just the fascism thing. Lewis and Pound were left-wing Fascists, although Pound was a raving anti-Semite and Lewis extremely sexist and homophobic. But Lewis was much more conservative, relatively, both politically and personally, by mid-century, whereas Pound was still incredibly glamorous, unrepentant, radical and mad…perhaps faux mad…a much more literary life-arc. Plus he was Kevin Bacon, so you couldn’t get away from Pound, but (at least my older teachers) seemed to think Lewis was just kind of boring. He didn’t lend himself to either formalist or biographical criticism.

The symposium I just went to, though — almost every paper talked about Lewis, and Jameson himself gave a marvelous talk about his Timon of Athens drawings, serious intellectual high. I think there’s going to be a proceedings…

Sorry, I should have specified “anti-leftist academics.”

I think the main reason Lewis and Vorticism suffer critically is geographical, as Alex indicated but for a specific reason which is that English literary and critical discourse has been more anti-modernist than European or American critical discourse. Kenner talks about this in his book A Sinking Island, quoting many anti-modernist comments from mainstream English figures. Lewis’ champions are often Americans, Canadians, French, or Italian.

Jeet, do you think they only suffer critically at home in the UK, or are you saying that the lack of attention they get in the UK damages them even in the US/Canada/France?

Just in my personal experience, they used to be marginal, and then became more talked about along with “modernisms”, as Eric said. But that’s entirely in the US and just anecdotal – I was surprised to hear they’re still marginal.

I’m trying to sort out the idea of an anti-Modernist UK with Eric’s point that Alan Moore is the most modernist (most-modernist?) of contemporary cartooning…

Eric:

“Single paintings or sculptures are usually seen as, or in, a single instant in time, but they do not also depict sequence.”

“Usually” is right and certainly not if we talk about International Gothic painting http://tinyurl.com/3ah32rt or, even, early Renaissance: http://tinyurl.com/37ys5pm

Your two readings are Gérard Genette’s linear and tabular readings of comics.

I miss a great modernist in your essay: Cliff Sterrett.

Eistein an Minkowski’s spacetime is one of the reasons why I don’t buy the attacks (Lessing) on the ut pictura poesis aesthetics… But that’s an anti-modernist point of view, I suppose…

Which means that modern comics are part of modernism as a mass medium, but were too impure (too mixed-media) to be accepted as high modernism proper.

English literary and critical discourse has been more anti-modernist than European or American critical discourse

Kenner’s point-of-view on this is very idiosyncratic, to say the least. As I recall, he didn’t consider Bloomsbury modernist; he felt they were essentially late Victorian. When one argues that To the Lighthouse shouldn’t be considered modernist fiction, as Kenner essentially did, it raises the question of whether one is being deliberately provocative, if not altogether obtuse. Kenner’s a great critic, but he’s pretty much a lone voice on this point.

Right…Kenner, if I remember right, pushes Lewis, but ignores or downplays Woolf. This is just silly…but Kenner went for the “Men of 1914” idea (or made it up? Or was it Ellmann?)…As a “lone voice,” Kenner was a pretty influential one. Woolf was often thought of as a lesser modernist from the 1930’s, until the ’60s, when the feminist movement revived her.

Kenner’s an influential voice, but I don’t think that extends to his views on Woolf and Bloomsbury. His major writing was on Pound, Joyce, and Eliot, wasn’t it?

The book Jeet cites, which was where he made those arguments, was published in 1988, a time when it’s hard to see them as being taken as anything but perverse.

Yeah, Robert Stanley Martin is right about this: the influential Kenner is the author of The Pound Era and a host of subsidary books (on Eliot, Lewis, Joyce and Beckett). The Kenner of A Sinking Island is something of a crank (not unlike his heroes). Although Kenner’s point about a general hositility to modernism in British culture is not without validity, no matter how crankily he might have made it. There’s no question that Lewis and Vorticism were for many decades seen as outside the mainstream of English art.

The phrase “men of 1914” was coined I believe by Lewis himself in one of his memoirs, perhaps Blastings and Bombardeerings.

@ Domingos

So, Genette wrote specifically about comics somewhere? Can you tell me where? I’m a Genette fan….but somehow missed that. Or was I misreading your comment?

@Jeet

One could also make a case that U.S. culture was hostile to modernism as well. We certainly have a strong philistine streak here, and the philistines aren’t exactly quiet about it. But as long as there were prominent publishers, galleries, and critics promoting the work, I’m not sure it matters. On the literary side in England, T.S. Eliot was a pretty major editorial voice, and it’s hard to think of any three critics more respected in their day than him, F.R. Leavis, and George Orwell.

In defense of the downplaying of Vorticist art, it’s pretty easy to see how, despite Lewis’ bluster, it could be seen as retreading the same ground as Cubism and Futurism. The two most prominent British artists of the High Modernist period were Ben Nicholson and Stanley Spencer, and their work has a distinctively modernist bent.

Sorry if I seem to be pummeling you here, but I have a hard time going along with your statement.

Eric: I’ll save Domingos typing it out again (this came up in another thread, I too am a Genette fan):

“…the comic strip…which, while making up a sequence of images and thus requiring a successive or diachronic reading, also lend themselves to, and even invite, a kind of global and synchronic look–or at least a look whose direction is no longer determined by the sequence of images.” (Narrative Discourse, 34)

Thanks Derik,

Funnily enough, I think I read that whole book (maybe before I started to think of these issues, though)…and even recently taught a chunk of it. I’m definitely getting old…

F.R. Leavis, by the way, was another important critical canon-maker who basically ignored Woolf, or thought little of her. For Leavis, it was D. H. Lawrence who was the modernist par excellence…making him a key player in The Great Tradition.

Some of this shows how much canons are a product of political fortune. Feminists revived Woolf (and she remains one of the most studied figures of modernism to this day), and Lawrence’s gender politics made him a bit less palatable to the back half of the 20th century. Lately, I think Lawrence is experiencing a bit of a revival…but I could be wrong about that.

Eric and Domingos: I’m resisting the notion that “simultaneous” in the Einsteinian sense is the same as “synchronic” in the structuralist. Did Genette reject the more radical poststructural sense of synchrony?

I think you don’t need Woolf for Bloomsbury to be important to modernism: you’ve got Forster, and Keynes, and Bell and Strachey, and Fry, and they published Eliot and the first English translations of Freud.

Bloomsbury wasn’t just influential on literary fiction — it was extremely influential on literary criticism as well, through Strachey and Bell, as well as Leonard Woolf’s biographies and memoirs (lit crit was still heavily biographical at that time). So Bloomsbury’s biases directly shaped the critical understanding of British modernism.

I mentioned it somewhat flippantly above, but Lewis started out as part of Bloomsbury, working at the Omega Workshops, and had a falling out with Fry et al. So Bloomsbury modernism excluded Vorticism, almost by definition but certainly by history.

I wouldn’t call that a “geographical” cause, although it does represent a bias against “modernism” in the Vorticist sense within Britain. But it’s a different modernism, not an anti-modernism…unless you follow Keener in saying Bloomsbury was late Victorian, which I agree with RSM is too much.

@Robert Stanley Martin. Leavis was a major critic and he appreciated a few (very few) modernist writers such as Eliot and Yeats but he was pretty actively hostile or indifferent to modernist fiction and modernism in the visual arts. His remarks on Lewis, Joyce, and most post-Eliotic poetry tended to be very dismissive, to say the least. (And as Eric mentioned above, Leavis and the Leavisites weren’t too friendly to Virginia Woolf either).

The same with Orwell, a great essayist in the Hazlitt tradition, and someone who appreciated Joyce and Eliot, although not a lot of other modernist fiction. And Orwell’s best literary essays — the one’s on Dickens, Tolstoy & King Lear — were on pre-modernist art. One major exception is the essay “Inside the Whale” but it’s a fairly eccentric piece although very interesting, but not enough to make Orwell a major critics of modernism.

I think the figure to compare Orwell and Leavis to would be F.R. Leavis who, in Axel’s Castle and elsewhere, was a consistent champion of modernism.

Of course the United States had it’s share of philistines (Ulysses was after all banned till the early 1930s) but it’s also the case that, as with Wilson, many of the pioneering critics, collectors and museum curators who made the case for modernism came from America or Europe (or in the case of Kenner, from Canada).

Again, Kenner’s A Sinking Island is a flawed book in many ways, but it does make a striking case that England had a powerful middlebrow book culture that really resisted modernism more intensely than either America or Ireland.

Jeet, which Leavis are you talking about in your first paragraph? Eric and RSM were talking about F.R. Leavis, so I thought you were, but then in your third paragraph you say “compare Orwell and Leavis to F.R. Leavis”? Let me know and I’ll edit the comment so there’s a first name in there…

Uh, Jeet? Axel’s Castle was written by Edmund Wilson. If you’re going to launch into one of your pedantic diatribes, you should make sure to get your facts straight.

I don’t claim to have read all of Leavis and/or Orwell’s critical work. I’ve only read select essays. However, those essays, such as “Inside the Whale” and Leavis’ discussion of “The Waste Land,” are very important works in the canon of modernist criticism, so forgive my mistake. I tend to think of writers and whatnot in terms of their most known work, not what percentage that known work is characteristic of every jot and titter they turn out.

Sorry, I meant Wilson when I wrote F.R. Leavis above (as should be clear since I say the figure to compare “Orwell and Leavis” to is the author of Axel’s Castle. The point being that Wilson, the American, was a more forthright champion of modernism than either Orwell or Leavis, although I’d agree that Orwell was a better essayist than Wilson and Leavis, in the end, a more important critic than Wilson. But my larger point is that if you look at Wilson (and his peer Clement Greenberg, Harold Rosenberg, many of the Partisan Review writers) you’ll find a more receptive audience for modernism than anything in England. I think that’s a fair point, and explains some of the difficulty Lewis had in gaining a critical foothold in England (which is the original point of contention).

British tendencies towards anti-modernism may be more conspicuous with visual art than writing. I don’t mean to go into a Vernon Young mode here, but the proclivities of English tastes in visual art tend to be very literal-minded. There seems to be a cultural predisposition against the visual abstraction that was the hallmark of modernist art. There aren’t many British painters or sculptors of note from the past century, at least not compared to France, Italy, or the U.S. (Nicholson, who is probably the most accomplished, lived and worked primarily in France, and that may not be conincidental.) One can see it in film, too. The most accomplished British filmmakers, such as Lean, Reed, and Hitchcock, certainly aren’t known for being poetic or suggestive, and there really wasn’t the sort of film renaissance after World War II in England that one saw in pretty much the rest of the world.

Ah, ok, so it’s the third paragraph that has the glitch.

Jeet, the problem with saying that Leavis was “hostile to modernist fiction” is that Leavis was himself writing during the “modernist” period: he was a modernist writer and he wasn’t fully consistent one way or the other in his opinions about his contemporaries. The cult of personality that arose around him was very much a Modernist phenomenon. So you have to take into account not just the impact of what he said, but also the way he said it, and in what contexts. Current critical practice would see Leavis himself as a figure of modernism, not a mere commenter on it.

George Watson has a “Hudson Review” essay from 1997 called “F.R. Leavis: The Messiah of Modernism” where he says “he was the crucified hero of Modernism, and those who denied him, in that mythology, were worse than opponents; they were the enemies of civilization.” But he ALSO says that Leavis “was the last Victorian.” And both are demonstrably correct!

So drawing a clear line between Victorianism and “modernism” misses precisely the sense in which Leavis’s impact is most directly felt on literary critical appreciation of Modernism, even the literary understanding of what Modernism was.

It seems like you’re also implying that the New Criticism isn’t a modernism, which I think is a mistake. But you’re right that the New Criticism is antithetical to Vorticism: we haven’t mentioned I.A. Richards, but The Principles of Literary Criticism was written in 1924, only six years after Lewis’ Tarr, and paraphrased Corbusier (“a book is a machine to think with”). Yet Richards lacked even the faintest trace of the anarchic, libertarian avant-garde philosophy characteristic of Lewis and Pound. Richards’ paramount virtue is stability.

So it’s certainly the case that this would have impeded the appreciation of Vorticism among literary critics — in Britain and in America, at least, where Richards and Leavis were so influential.

But that doesn’t mean that those British critics were “anti-Modern”: Cambridge modernism WAS modernism — it just wasn’t the same modernism as Vorticism. So are you saying that Vorticism (et al.) is what we SHOULD think of when we think of modernism, rejecting the idea that there are “modernisms”? I can’t really buy the notion that Richards is a “late Victorian,” although I can buy it for Leavis. But both of them were so indispensible.

I just — I feel like I’m really not following you…

I probably should have said this earlier rather than stumbling in on the more advanced conversation, but…what really is the difference between vorticism and something like futurism? I know Pound rejected the second, but is there a coherent reason? Or is it basically just, they’re not me?

If I remember correctly, The Partisan Review, and Orwell in particular, were explicitely anti-Lewis during the ’30s, so they’d have had to overcome the explicit objection for the implicit resonances to make a difference. I will search for the reference.

I think I see the general problem I’m having though. This, Jeet:

is too general. You find a more receptive audience for anarcho-individualistic modernism, but that’s not the only thing you find in America. There was The Partisan Review, but there was also The Kenyon Review. Both were Modern…

America’s emerging New Critics mimicked British Modernism very closely, and British perspectives were very influential here. Using “modernism” this way, as if it’s this one thing that excludes Bloomsbury and Cambridge in favor of Pound and Hulme, is unbalanced and incomplete.

I completely agree with the point Robert Stanley Martin made in comment #33, which I think gets closer to explaining the antipathy towards Lewis than anything else that’s been said so far.

It’s true that Leavis was himself a modernist writer, but that doesn’t preclude his hostility towards other modernists. The same is true of Lewis himself; he stylized himself as The Enemy and spent an enormous amount of energy attacking non-Lewisite forms of modernsim. In that sense Lewis and Leavis were mirror images of each other.

Noah — Mr. Futurism himself, Marinetti, considered Vorticism to be a British version of Futurism. The Vorticists rejected the connection for various reasons, none of which are really definitive. The one that makes the most sense to me is that they were less enamoured of machines and speed and violence and less fully Fascist. They were also kind of the first instance of Cool Britannia — “Englishness” was very important to them, although it was an anti-Victorian Englishness that had a real anarchic core. They also saw themselves as more abstract than the Futurists: they called Futurism in Blast “the last form of Impressionism” and said “we do not depend on the appearance of the world for our art.”

So I mean, there’s a coherent reason, but it’s sort of like saying that a yellow apple isn’t a red apple.

Caro–

I’m still getting over the shock of Jeet saying he completely agrees with something I wrote, but is it your sense that the basis of Lewis and others for distinguishing Vorticism from Cubism and Futurism was more nationalistic than anything else?

Jeet, I agree with Robert’s point in 33 too — but I also think it’s a mistake to treat Lewis as if he were a visual artist exclusively.

Are you claiming that your insights apply to Lewis’ reception within literary criticism, or just within visual art? Because I can certainly see that the causes of those two would be different.

But from the standpoint of literary criticism, the idea of Britain being sweepingly “anti-Modernist,” and then seeing that as a cause for the Vorticists’ marginalization — more than Lewis’ contentious relationship with Bloomsbury, more than his own polemical style, more than the legacy of his nasty politics, more than Pound’s letters from Italy and subsequent madness, more than Lewis’ own comparative lack of sophistication and inconsistency in comparison with Pound and other major modernist writers — that really seems vastly oversimplified to me.

If it is nationalistic, that’s pretty funny considering that (a) Pound wasn’t British, and (b) he was so enamored of Mussolini that he arguably betrayed his country on Italy’s behalf.

Because of this discussion I’ve gone back to read some of Pound’s poetry and while there are certainly good bits, I am mostly impressed again by what an asshole he is….

Robert, I think it was more motivated by their individualism and their desire to not be subsumed into someone else’s movement — which may boil down to Lewis’ ego and the point Jeet makes. My sense is that the nationalism was more marketing, a tool for that differentiation…here’s what the exhibition catalog says:

Noah — Well, my theory is that you can trace a direct line in American “futurism” from Pound and Hulme to Ayn Rand to the Nixon/Khrushchev Kitchen Debates, so … assholes abound!

Noah–

Another shock! You and Harold Bloom agree on something. (Of course, you only called him an asshole and Bloom told us he thought Pound deserved to be hung, but still.)

At the time Pound was very Anglocentric. I’m not sure if it’s online, but if you ever get the chance, go and dig up the letter he wrote to T.S. Eliot’s father imploring him to support Eliot’s decision to stay there and not return to the U.S. You’d be hard-pressed to find anything more rah-rah about England in general and London in particular, at least relative to the United States.

On the “did Pound deserve to be hung” problem: I read a passing reference somewhere recently about how the psychiatrist who testified to Pound’s insanity (thus keeping him from being hung) lied because he thought Pound was such a great poet — anybody know anything about that?

Yeah; it’s the whole disliking fascist traitors thing. Even people who disagree on most things can agree on that.

I’m against the death penalty, but yeah, I get where Bloom is coming from.

Robert Stanley Martin wrote: “British tendencies towards anti-modernism may be more conspicuous with visual art than writing. […] There aren’t many British painters or sculptors of note from the past century, at least not compared to France, Italy, or the U.S. (Nicholson, who is probably the most accomplished, lived and worked primarily in France, and that may not be conincidental.)”

This is a very interesting discussion. I hesitate to contribute with a tangent, but here goes. I am slightly amazed that anyone would consider Ben Nicholson the most accomplished English modern artist of the past century though. Obviously these are matters of personal taste, but I rate Anthony Caro, Francis Bacon, Howard Hodgkin, Henry Moore, David Hockney and Gilbert & George higher. Probably others if I can think of them.

What does seem true is that as far as modern art goes, England was slow off the starting block. The number of significant artists out of England really didn’t start to grow into something substantial (at least looking at it from outside) until after WWII and really until the 60s. This probably has something to do with England’s conservatism (in terms of visual arts), but may also have to do at least in part with the devastation visited on it by the wars. How many unknown great painters died battle?

I think England’s underachievement in visual arts predates modernism. England didn’t ever have a Reubens or a Rembrandt; the visual tradition compared to Holland or Germany or France or Spain just isn’t that impressive, especially compared to their overwhelming achievements in literature (a number of important English writers (Wilfred Owen, Isaac Rosenberg) died in WWI, but England’s postwar literary output is still impressive.)

It’s hard to say why this should be…you could blame it on Puritan iconoclasm, I suppose.

Robert Boyd — OMG the Warhol letter to the Smithsonian (follow Robert’s name-link, people). I was on vacation this weekend; I hadn’t seen that. WOW.

I think it would be interesting to see a list of all the known artistic figures who died in the wars. Just for the Vorticists, both T.E. Hulme and Gaudier-Brezska were killed during WWI, that I know of.

England had important decorative arts movements, though, including Bloomsbury.

Just a couple of caveats–

* outside of anglophone academia, Bloomsbury doesn’t exist, really. The exception is Woolf, and that dates only to the sixties.

* Orwell wasn’t necessarily considered an important critic by his contemporaries: we project our current esteem for him retrospectively.

As a critic, he was often pretty retrogressive, speaking in the tone of ‘good plain common sense’ (my phrase, not his.) Read him on Dali, for instance.

This is a digression, but I can’t resist retailing an anecdote told by Max Beerbohm.

Beerbohm was at a café terrace in France with Pound and the latter’s parents. These apparently thought the sun rose and set on their brilliant Ezra.

Pound was expatiating at length, tossing out pensées and epigrams like confetti.

At one point, he stated that ‘Louis the Sixteenth was, of course, the only true master of eighteenth-century French prose’.

At which his father nudged Beerbohm in the ribs and whispered, ‘That kid knows EVERYTHING!’

Robert Graves did a severe takedown of Pound as a poet…

Taste does play into it, which was why I included the qualifier “probably.” I’m much more attracted to pre-WWII work than stuff done after it, so that may be the source of our difference. (Everyone you mention is post-WWII.) However, I do think that Nicholson ranks every English artist from the first half of the century.

I’m not really sure that the wars’ impact on the populaces made that much of a difference. France and Germany certainly sustained far higher death tolls than England during the first World War, and they were the centers of the Western art world from the end of the war at least until the Depression.

Well, Alex, there was this economist associated extremely closely with Bloomsbury, one named John Maynard Keynes. The Cambridge Companion to Keynes has an entire chapter devoted to the influence of Bloomsbury values. I think it’s indisputable that Keynes matters beyond Anglophone academia…

I’d say E.M. Forster matters more broadly as well, although less so, (and Woolf’s acknowledged, with the late-comer caveat), but I suppose I also thought the question was about the reception of the Vorticists within literary critical circles, and Anglophone academia was very important to Anglophone literary criticism!

I don’t think there’s any question that Pound was completely unbearable in person and entirely out of step with post-war sensibilities. None of that makes him less influential or important though — as a critic, an editor, as a cultural and critical lightning rod.

Agreed about Pound, but in what way has Bloomsbury impacted Keynes’ economic theorising at all? A mere social connection is risible.

@Alex Buchet. Some people, notably Joseph Schumpeter, have seen a connection between Keynes’ economic theories (notably the celebration of consumption over production) as linked the sexual ethos of Bloomsbury. Famously, Schumpeter wrote about Keynes, “He was childless, and his philosophy of life was essentially a short-term philosophy.” I think this argument is kind of homophobic, but there might be other, less, bigoted ways of connecting Keynes’ economics with the social vision of Bloomsbury.

Bloomsbury wasn’t really a “social” club, it was more a commune. And it’s guiding ideology was “a synthesis of socialism and liberalism.” That’s very Keynsian!

The specifics of the influence are hotly debated by economic historians: you can read the Cambridge Companion essays online. That link goes to the main chapter which discusses the role of Bloomsbury ethics on Keynes, and is the most direct answer to the question about his economic theory. Search for Bloomsbury and it comes up in a few other places too, including the argument that Bloomsbury’s influence on Keynes’ rhetorical style hurt his reception within professional economics.

If you have access to the Social Science Research Network (I don’t think it’s US IP limited), there was also a symposium on Keynes’ Bloomsbury connection held by the Center for the History of Political Economy, also at Duke University. If you click on the download link at the top you get the text of all four papers as a single PDF; the first three talks were given by professors of economics and address the question you raise. This stuff too far out-of-field for me to easily summarize, but the first paper, for example, links Bloomsbury to Keynes’ abandonment of the simple rational actor hypothesis.

All that’s still Anglophone academia, yes, but I don’t see how it would be irrelevant to economic historians in other countries, provided they were actually interested in Keynes…

The first essay in the PDF I link to also makes the claim that Keynes’ emphasis on the demand side of markets was shaped by the reality of the art market: Bloomsbury’s recognition that the problem in art wasn’t getting artists to produce, but other people to buy. Much less homophobic!

Wow, I didn’t realize Pound actually knew Beerbohm. It’s that Kevin Bacon thing….

One of the most unpleasant bits of “Mauberly” (which is what I was rereading) is a short section on Beerbohm (who appears under a transparent alias) in which Pound refers unpleasantly to Beerbohm’s Judaism. It’s hard to say exactly what Pound means, as usual, but he seems to be either condemning Beerbohm for hiding his Judaism and assimilating, or else condemning the age for allowing Beerbohm to have assimilated. Probably both.

“The sky-like limpid eyes,

The circular infant’s face,

The stiffness from spats to collar

Never relaxing into grace;

The heavy memories of Horeb, Sinai, and the forty years,

Showed only when the daylight fell

Level across the face

Of Brennbaum, “The Impeccable.”

I have trouble reading that as anything but him sneering at the idea that a Jew could be seen as impeccable.

The kicker is that Beerbohm wasn’t Jewish. Pound just thought he was.

He’s TOTALLY the Kevin Bacon of Modernism. But Kevin Bacon is SO much nicer (as far as I know. It isn’t saying much.)

The phrase “the impeccable Beerbohm”, though, is Pound’s himself, from a 1918 issue of the Little Review. Your reading still makes sense though, and the Little Review essay doesn’t appear to be online so the anti-Semitic sense could be at play in that essay as well.

From Wikipedia it looks like others speculated that Beerbohm might be Jewish, though he always denied it.

The “impeccable” is probably a play on Shaw’s dubbing Beerbohm “the incomparable Max”.

Working my way through those papers on Keynes…not convinced!

Yes; definitely a play on Shaw. I knew it wasn’t Pound’s idea in the first place….

BTW, Noah, in the coming year I want to write a post or two or three or more on Beerbohm…I admit it, I’m a raving Maximilianist…that OK?