Unless you’ve been living in a cave, you know that Iron Man 2 premiered this month and made a eleventy billion dollars on its opening weekend. Next summer, Marvel hopes to replicate that success with Thor, followed by Captain America, and then an Avengers movie in 2012. Plus there are rumors that the Spider-man, X-men, and Fantastic Four franchises will all get rebooted within the next two years. But with it’s A-list IP’s already locked up in movie deals, what new ideas can Marvel bring to the big screen in 2013? The only superheroes that Marvel has left are the C-listers: characters that, while not completely obscure, never quite reached the big leagues. And if you want to sell the C-list to Hollywood executives, you need the right pitch. Speaking of which, here are my pitches for some Marvel’s lesser known characters.

The Immortal Iron Fist

Cover by David Aja

Origin

Wealthy industrialist Danny Rand travels to Asia and discovers the hidden city of K’un L’un. He learns kung fu. He beats up bad guys using kung fu.

The Pitch

Wuxia for the American mainstream.

Demographic Appeal

White males who love everything about kung fu flicks except those pesky, non-white actors.

Main Reason Why This Movie Could Fail

There isn’t exactly a shortage of martial arts movies.

Solution

Lots of stunt casting: Michael Dudikoff will play Danny’s father, Wendell. Chuck Norris is his uncle. Brief cameo by Jackie Chan.

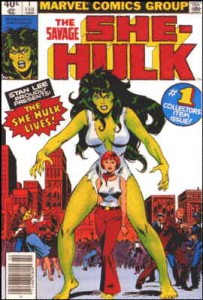

The Savage She-Hulk

Cover by John Buscema

Origin

Jennifer Walters was a shy, unremarkable attorney in Los Angeles until the day a local crime boss had her shot. Fortunately, she was being visited by her cousin, Bruce Banner (a.k.a. The Hulk), who gave her a blood transfusion that saved her life. But it also transformed her into — The Savage She-Hulk!

The Pitch

So you didn’t care about the last two Hulk films, but this one has a giant, green hottie!

Demographic Appeal

Men who are into tall, green women.

Women who desperately want to watch any movie starring a superheroine, even a Hulk-spinoff.

Main Reason Why This Movie Could Fail

Self-sabotage: Hollywood believes that blockbusters starring women will flop, thereby ensuring that they’ll screw it up.

Solution

When in doubt, just rip off something with a proven track record.

Pander to Sex and the City fans. She-Hulk teams up with Spider-Woman, Ms. Marvel, and the Scarlet Witch to talk about life, love, and shoes, all while saving the Earth from the Skrulls.

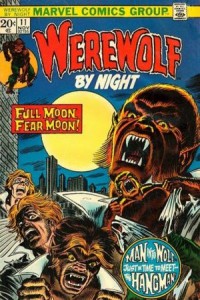

Werewolf by Night

Cover by Gil Kane and John Romita, Sr.

Origin

Jack Russell was a normal teenager until the day he turned 18, when he learned of a terrible curse that afflicted his bloodline. Jack’s parents had emigrated from Eastern European Country hoping to escape the curse, but curses know no borders. Now, in the light of the full moon, Jack Russell becomes a werewolf — by night!

The Pitch

Are you sick of zombies and vampires yet? How about some werewolves?

Demographic Appeal

Fans of superhero/horror hybrids like Hellboy.

Fans of cheesy dog puns.

Main Reason Why This Movie Could Fail

No evidence that a substantial number of people are clamoring to see a werewolf movie.

Solution

This is a tough one. But even Blade ended up as a moderately successful franchise, so the right idea might be to make it rated-R.

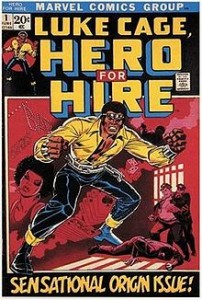

Luke Cage: Hero for Hire

Cover by John Romita, Sr. and George Tuska

Origin

As a teenager, Luke was wrongfully convicted of a crime he didn’t commit and sent to prison. In exchange for an early parole, Luke agreed to be the subject of secret experiments that unexpectedly gave him superpowers. Luke then busted out of prison and decided to clean up his old neighborhood in Harlem — but only after he gets paid.

The Pitch

Shaft with superpowers.

Demographic Appeal

Black males.

White males who fantasize about being black males.

Main Reason Why This Movie Could Fail

Institutionalized racism that pervades the American film industry at every level.

Solution

Will Smith.

X-Men Origins: Cable

Cover by Rob Liefeld

Origin

Here goes … Cable is Nathan Christopher Summers, the son of Scott Summers (a.k.a. Cyclops of the X-Men) and Madelyne Pryor (a clone of Jean Grey, a.k.a. Phoenix of the X-Men (who was dead at the time), though Scott didn’t know at first that she was a clone) who later became the demonic Goblin Queen. Cable was the product of a secret experiment by Mr. Sinister (an evil, immortal geneticist who I think is also an ancestor to Scott Summers), who wanted to create the ultimate mutant that would defend him from his master, Apocalypse (an immortal mutant who wants to start a race war between humans and mutants). While still a baby, Cable was kidnapped by Apocalypse and infected with the techno-organic virus that turned him half-machine. To save their son, Scott and Jean (Madelyne had died by this time and her essence and memories were absorbed by Jean … it’s a long story) decided to send Nathan to the future with a time-traveling group called the Askani (which was founded by Rachel Summers, the daughter of Scott and Jean from another possible future … actually, it’s not that important) who promised that the technology from their era could halt the spread of the T-O virus. In the distant future, the Askani saved Nathan (but only after they cloned a backup baby, which was stolen by Apocalypse and raised to be the villain Stryfe … which is another long story) and the boy became Cable, leader of the resistance against Apocalypse and a lover of huge guns. To save the future (or something equally vague, I don’t remember), Cable traveled back in time to shoot things and put together a team of young mutants who wouldn’t play by the rules. And after that, things start getting complicated.

The Pitch

X-Men! Guns! Time travel! Guns!

Demographic Appeal

14 year old boys.

X-Men completionists.

Main Reason Why This Movie Could Fail

Cable’s 15 minutes of fame ended two decades ago.

Solution

Guest-starring Wolverine!

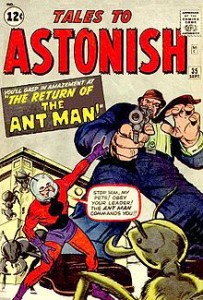

The Astonishing Ant-Man

Cover by Jack Kirby and Dick Ayers

Origin

Scientist Henry Pym discovered a new subatomic particle (dubbed Pym Particle) that allowed him to shrink to the size of an ant. He also created a helmet that can telepathically control ants. Along with his girlfriend, The Wasp, Pym fights criminals and Communist spies [replace with Russian Mafia] with the power of being very small. And ants.

The Pitch

There’s trailer for Iron Man 3, but it’s at the end of the movie.

Demographic Appeal

???

Main Reason Why This Movie Could Fail

It’s about Ant-Man.

Solution

Release in February when there’s absolutely no competition.

Tigra: The Motion Picture

Panel by Mike Deodato

Origin

Greer Grant was just another superhero wannabe until the day she was badly injured in a terrorist attack. Rescued by a long lost race of Cat People from Baja California, Greer was given a second chance at life when they magically transformed her into superhuman hybrid. In a bikini.

The Pitch

Sexy cat-chick in bikini.

Demographic Appeal

Bikini enthusiasts.

Neko-girl enthusiasts.

Furries.

There’s probably a couple fetishes that I’m forgetting…

Main Reason Why This Movie Could Fail

See She-Hulk

Solution

Tigra — in 3-D.