Hi, everyone, I’m Jason Michelitch, a semi-regular contributor over at Comics Alliance and a longtime-reader/sometime-commenter here at Hooded Utilitarian. Noah kindly invited me to write this guest post for HU, which I’m going to kick off by admitting openly how many times I’ve watched the movie Face/Off, inviting the scorn and dismissal of you fine, educated people. Let’s boogie!

I was watching Face/Off the other day, for maybe the baker’s dozenth time since catching it first run in the theater in ’97, and in the middle of the film, I began to wonder, “Why am I watching this?” I mean, the broad answer was obvious: I love Face/Off. I would watch it anytime. I would watch it right now. But why?

Face/Off, for those who have never seen it, is a very classic hero/villain adventure story. John Travolta plays a high-ranking FBI supercop who has the face of a captured super-terrorist played by Nicolas Cage surgically grafted onto his skull so that he can go undercover as Cage and pump info out of the super-terrorist’s gang. Nic Cage retaliates by stealing Travolta’s face, killing the people who know Travolta is undercover, and taking Travolta’s place at work and at home. The bulk of the film is then devoted to Cage-as-Travolta fighting to get his life back from Travolta-as-Cage.

Now, I don’t know if that sounds as awesome to you as it does to me, but whether it does or doesn’t, one thing is for sure: you already know how it’s going to end. I knew before walking into the theater in ’97 how it would end. That’s because, in a work of heroic fiction, the hero by definition will win. It’s foregone, every time. But, knowing that, I still not only wanted to see the film, but loved it and have watched it again and again. Why?

Why sit through any piece of heroic fiction when the end is pre-determined? Sure, there’s some pleasure to be found in pure plot mechanics — Sherlock Holmes running down precisely what type of mud he perceived on the dead man’s sleeve that made him realize the killer must be from Norway, and also one-legged — but that seems only temporarily diverting at best, like a magician explaining a magic trick. There’s no true suspense, no emotional resonance. A hero is, by definition, a protagonist who is (according to the surface text of the story) right and good and who will inevitably triumph over whatever obstacles are put in his path. Knowing this, what then is the point of enduring scenes that purport to put a hero in danger or threaten his mission? No matter how dire the circumstances, the hero will get through them, by definition of being the hero. Why sit through it once, and why return to it?

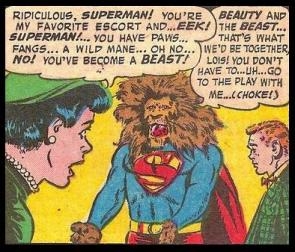

There’s a recurring complaint among comic book writers and fans about Superman: that Superman is the most difficult character to write for, due to his being so insanely powerful that it’s impossible to come up with an opponent that can pose a suffcient threat. This complaint has always seemed extremely odd to me. Of course you can’t come up with an opponent that can pose a sufficient threat to Superman — he’s the hero of the book. In heroic fiction, there is no such thing as a truly threatening opponent, because no matter how threatening the opponent, he is destined to lose. Sure, as a character, Superman has super-powers that make him impossible to kill and more or less allow him to do anything. But those powers are just the most obvious symbolic versions of the abilities of every hero in fiction. All heroes can’t be killed, and they can all do anything, insomuch as within the context of a given story, a hero will inevitably be able to do all the right things to defeat the obstacles in their way and avoid death. So Superman’s super-powers are really the generic qualities of all heroes, just given more obvous and literal manifestation.

So all heroes are Superman, destined for victory. What then to make of hero stories, which are primarily concerned with conflicts between said heroes and villainous foils? Since the focus of the story — the hero’s struggle — is preordained to end in heroic victory, doesn’t it become somewhat pointless to ingest these stories as stories? Yet we — and that’s not a rhetorical we, I mean me too — continue to ingest story after story of heroes and villains, not just in the action/adventure genre, but in romantic comedies, mysteries, even biographies. Why?

It seems to me that, while for any original, unpredictable story the conflict between characters would be the meat of the experience, in heroic fiction the formulaic structure reduces that meat to a repetitive rhythm. It’s a subversion of story, taking what would normally be the most important element of a narrative and making it a steady, reliable bass line, over top of which all manner of solo-ing might occur. It is the ancillary elements — visceral aesthetic pleasures, intellectal subtexts, smaller moments or stories residing within the master narrative — rather than the story itself, which provide the artistic meat.

In Face/Off, it’s the visceral pleasure of the acting I respond to first and foremost. Travolta and Cage take every piece of scenery that’s not nailed down, shove it in their mouths, and masticate furiously. If the story required me to react to either of them as real people, the performances wouldn’t work. They’d get in the way of me internalizing the conflict and feeling the impact of the choices made by each player. But because their relationship is established and locked by the beginning of the film, and can only end one way, it frees both the actors and the audience to go crazy with the moments inbetween. So we get Travolta embracing contempt and sleaze as he manipulates everyone around him for his own amusement, and we get Cage pinballing all over the emotional spectrum in the way that only he and his thoroughly crazy eyes can. David Lynch once called Cage the “jazz musician of actors,” and when the story beats are pushed to the background and locked into an immutable groove, Cage can truly let loose and skronk in the foreground. In the space of one film, we get Cage as hyper-sexualized glam-villain, wild-eyed prison rioter, drug-addled maniac, vengeance-driven rage monster, and hysterically emotional wrong man — and for all but the first of those, he’s the good guy.

There are other pleasures in the film. John Woo’s action set pieces are excellent, and the script by Mike Werb and Michael Colleary is pretty inventively weird and unapologetically pulpy and over-the-top. From the practically-silly but mythically-resonant concept of swapping faces, to dystopic SF flourishes — like a high-tech secret prison for the world’s most cartoonish apolitical terrorists, where everyone is locked down by heavy magnetic boots and mood-controlled by 40-foot nature videos and electric shock therapy — there’s more smarts to the script than would be assumed on first glance.

But for all I admire in the film, there’s a converse, which is that I fear it can never be more than the sum of its parts. How a story ends is, obviously, a crucial choice on the part of the storyteller. With the predetermined structure of hero fiction, that element of the story — the end — is off the table. The crafting of a hero story becomes an exercise in filling up the space between obligatory elements as interestingly as possible — which can be incredibly rewarding and entertaining, but can it ever fully cohere when anything subversive or innovative in the story is subservient to the overall structure?

Take the pleasure of Nic Cage’s acting. The comfortable heroic structure gives him the space to run rampant without the audience fretting about the ultimate destination. This can be seen as both a freeing opportunity for Cage and those who wish to watch him work, or it can be seen as an overly safe, cowardly choice by the filmmakers to indulge in Cage’s insanity but with a safety valve in place, preventing us from seeing where his lunacy might lead when taken off the leash. Werner Herzog, in contrast, is much riskier in his use of Cage’s mad energy in Bad Lieutenant: Port of Call New Orleans. There is no sense in the film of a predestined end, of a way the story must go, and so Cage’s acting choices become much more dangerous for the audience, as we do not know where they will end us up. As much as I would never give up Cage’s performance in Face/Off, his performance for Herzog is just as unhinged, but is also in service to a more cohesive artistic whole, being unhampered by the inevitability of the heroic narrative.*

It seems that the only hope for a piece of hero fiction to be an artistically cohesive piece is to acknowledge and work with the inherent limitations of its form. The worst thing that a creator of hero fiction can do is presume that the story beats of the hero’s struggle and triumph are important at all beyond the immediate visceral pleasures they can provide. This was the mistake George Lucas made with the first Star Wars film, in my opinion. For the original 1977 movie, Lucas painstakingly plotted out Joseph Campbell’s hero’s journey, and then adorned it with stunning visuals and sound work. It’s a dazzling aesthetic experience, but there isn’t much else to it. All of the dialogue and character traits are geared around the elements of the heroic struggle, rather than being interesting on their own and existing within the comfortable structure. Lucas’s quotes from Triumph of the Will at the end of the picture are apropos, because like Riefenstahl’s film, Lucas’s technical and structural wizardry is vacuous and empty triumphalism, existing to imbue glory to the subject at hand without any consideration of the subject beyond that limited goal.

The second and third Star Wars films bring more to the table, though how much more is certainly debatable. The second, Empire Strikes Back, in particular, having at least some character development as opposed to the first film, and culminating in an impressively grandiose stab at the time-worn theme of the conflict between fathers and sons, ignores the heroic structure in favor of more rewarding moments. If you take the Star Wars trilogy as one three-part piece of heroic fiction, it’s the non-formula middle chapter that provides the meat. If those films are worth revisiting (and I think there’s a valid argument either way) it’s because of Empire, not because the Death Star blows up twice. “May the Force Be With You” and “Let the Wookie Win” may have been the first lines to end up on a t-shirt, but I’ve heard enough random people from every walk of life casually quote “Luke, I Am Your Father” to convince me that it’s the non-hero story beats that provide the series’ lasting resonance.

The most constant and regular dispensers of hero fiction are the mainstream super-hero publishers, and for decades now they’ve been stuck in a mindset that it matters what happens to their heroes — who dies, who lives, whether or not they triumph, when of course eventually they will all live, and all triumph, so long as you wait around long enough. The grand-daddy of all dumb superhero event comics is 1992’s The Death of Superman, and it is a master class in misconceiving what is important in hero fiction. The story beats of Superman’s struggle against a deadly foe, his apparent death, and his friends mourning him take up vast amounts of space in the story, and all ring hollow — because the reader knows the story is just going through the motions, waiting for Superman’s inevitable return. There were dumb events before Death of Superman, but ever since then comics seem locked into nothing but as their chief storytelling strategy. And I suppose they have enough people who do care about such mechanical exercises in inevitability that for their bottom line, such story beats do matter. But I’ve always thought that the most artistically successsful super-hero stories were the ones that took the superhero’s inevitable triumph for granted and just made the most of the middle.

The Silver Age Superman stories edited by Mort Wesinger stand as a perfect example to me. When those stories worked (and they were of course wildly uneven) they had the flavor of real myth to them. Not the kind of myth Kirby self-consciously tried to create, with epic heroes and villains slamming into each other at full speed, but the kinds of stories you really find in myth — immortal gods acting like fools, finding themselves transformed or in strange situations.

Superman has a lion’s head! Superman feels overshadowed by a tiny homonuculus of himself! Superman’s powers are operating in reverse! The stories would always resolve back to the status quo, of course, and often the resolution would take place in an off-hand, last-panel manner. I believe that’s because the writers and artists understood, either subconsciously or consciously, that the ends of their Superman stories didn’t matter. They would always be the same at the finish, so why not have as much fun as possible before the curtain call, when all the actors resume their places.

* Though Herzog is deferential to screenwriter Billy Finkelstein in interviews, he also admits to adding and altering elements of the story of Bad Lieutenant: Port of Call New Orleans, some based on improvisations by Cage, and in fact the end of the film — if memory serves, I don’t have the interview in front of me — has been claimed as a Herzog/Cage invention. Therefore, while BL: POCNO actually contains quite a bit of material that directly mocks the traditions of a heroic narrative (which would take a whole other essay to go into), it also serves structurally as a direct opposite, in that its end was determined through the process of making the film, rather than dictated by a structural formula.

** The Death of Superman actually did have one element which harkened back to the strange Weisinger days — after the death and the funeral, but before the inevitable resurrection, the storyline concerned itself with four random alternate variations on Superman who all claimed some sort of right to the throne. For a moment, the biggest of dumb stories obsessed with the wrong end of the hero reveled in a chaotic weirdness that was the only innovative or interesting part of the whole ordeal. Superman is a cloned teenager! Superman is a black man in a steel suit! Superman is a gun-toting cyborg! It was all short-lived, of course, but certainly worth noting in the context of the discussion.

“Lucas painstakingly plotted out Joseph Campbell’s hero’s journey…”; actually there are HUGE gaps in his interpretation. See Kal Bashir’s 510+ stage hero’s journey at http://www.clickok.co.uk/index4.html

i c we’re dealin w/ heroes here

no reason to rewrite the Iliad dear

more to Star Wars than meets ‘the eye’

lots of subtext, give it a try

tl;dr

:D

I would be perfectly happy if anyone else who commented wanted to also do so in rhyme.

Not in rhyme…but what on earth is that title a reference to?

I took the heroic cycle into the shop/

cause the wheels were bent and the seat was lost/

i was in despair till they recommended repair/

and I knew I would do it despite all the costs

One thing I was sort of wondering…this isn’t confined to hero narratives, is it? Romance is maybe even more formulaic in some ways. As are detective novels…it seems like it’s maybe an issue of genre….

In which case the predictability is probably a feature not a bug, right? (Not that that contradicts what you’re saying….)

Noah: No one is answering your question. You weren’t asking about the Fred Astaire screen test remark, were you: “Can’t act. Can’t sing. Balding. Can dance a little.”

And…I agree with some of the article but I prefer Hard Boiled to Face/Off.

Aha! It’s a Fred Astaire reference! Thank you!

I just saw Face/Off on Jason’s recommendation actually. I’d agree that Hard Boiled is better; I left that movie actually shaking — it’s over the top violence is just way, way more over the top, the exploitive use of children as props for the blood bath much more exploitive, etc. All in all a purer vision.

Face/Off definitely has its points, though. I think Jason captures them quite well; Nicholas Cage and John Travolta are both clearly having the time of their lives. I don’t like it as much as Jason does, but I was glad to watch it.

Not to mention the fun, slightly sloppy handheld (?) shot in Hard Boiled.

Detective fiction seems less predictable than your standard superhero series like Superman and Batman. At least, the “hero” can die.

I guess it depends on the detective fiction. Sherlock Holmes couldn’t die (despite Doyle’s best efforts!)

Hey Noah,

Sorry, was out most of the evening, so I didn’t get to answer the Fred Astaire question — I thought it might be a little obscure as a title, but it made me laugh, so I went with it.

I actually mention other genres in the piece. “Yet we — and that’s not a rhetorical we, I mean me too — continue to ingest story after story of heroes and villains, not just in the action/adventure genre, but in romantic comedies, mysteries, even biographies.”

I agree that romance and detective fiction are all subject to the same predictability, but I think the core of the predictability is in the use of a central character as a right and true hero. For example, you can have a romance that ends in tragedy, or that ends in complicated circumstances, but it’s rare that you have a romance with a clear, signposted hero in which the the hero doesn’t win the girl at the end. (Genders are obviously malleable, I’m just using the masculine as shorthand).

Straight detective fiction is usually a subset of hero fiction, with a central hero (like Holmes, or Poirot) solving the crime. I’d say Holmes’ resurrection is a clear sign of his stories ultimately being more about a hero winning than about a depiction of crime or detection — those are the ancillary elements to the heroic narrative that make the stories worthwhile. Stickier detective fiction without clear heroes and villains I’d more likely classify as crime fiction rather than straight detective fiction…although I honestly wouldn’t want to get too far into labeling things, as I don’t think it’s always productive when taken to extremes.

Also, as much as I have an insatiable love for Face/Off, Hard Boiled is obviously the better movie. I’d be a fool to try and argue that. I’ve always said the primary thing Face/Off is missing is Chow Yun-Fat…

Sean Michael Robinson: Thank you for rhyming.

And of course there’s a completely separate issues of the tradition of the Noble Heroic Sacrifice, though I suppose that can be integrated as a sort of heroic victory somehow, if I contort wildly enough.

black swan.

Pingback: Linkblogging For 17/01/11 « Sci-Ence! Justice Leak!