(Please click on all images — they’re much easier to see in the big versions.)

Over at The Panelists, in the comments to Derik’s really terrific post on Blaise Larmee’s Magic Forest, I’ve been harassing Charles Hatfield a bit about the theoretical status of “sequence” in comics studies. For me, the importance of sequence is always overstated in a way that I think limits what the term “comics” can be appropriately applied to and, even worse, emphasizes one subset of elements within comics – the sequential, narrative ones – at the expense of the metaphorical and structural aspects I find more interesting.

Charles asked me this:

can you remember a comic, or imagine a comic, in which some presumption of sequence did not play a part in your experience of it?

The phrase “some presumption of sequence” is pretty open – Charles clarifies later on that he includes any reading protocol in this category, so in this formulation, I either “read” the comic, in which case it’s sequential, or I don’t read it – in which case why isn’t it just visual art? That’s maybe loading the dice a little.

But all reading protocols aren’t sequential or serial. There are recursive reading protocols. In prose literature, writing that invites those recursive protocols generally accompanies more sequential narrative writing, it rarely stands entirely on its own, but it’s still a different reading protocol from the one we follow when we read sequentially. Metaphorical conceits often come together at the level of recursive reading. I can definitely think of examples of books where my experience of recursion played a stronger role than my experience of sequence. Charles made many useful observations about sequence in the comments that I’m just beginning to think through, but I wanted to offer up the best — and purest — example of recursive reading in comics that I could think of:

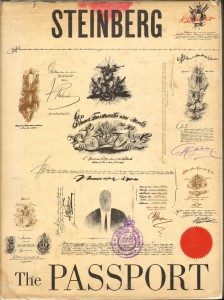

Saul Steinberg’s The Passport is my favorite “graphic novel” although I’m probably the only person who’d ever call it that. Composed in 1954, it is graphically forward looking:

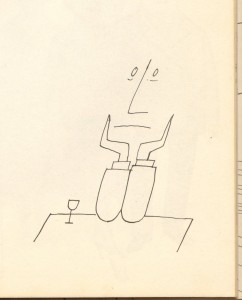

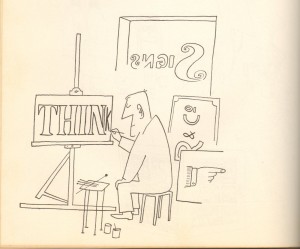

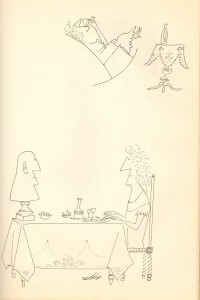

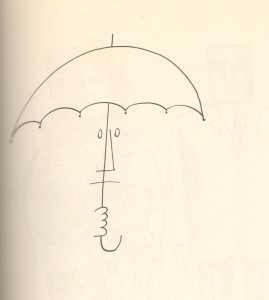

It has inventive drawing – such as this wonderful page exploring how little you need in a cartoon to make sense.

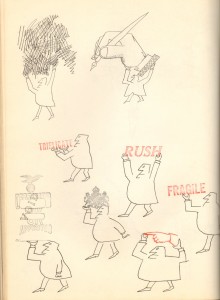

It has rollicking humor:

But most importantly it provides meaningful insight into the emptiness of America’s conformist and self-absorbed middle- and upper-class culture, which he critiques without any trace of schadenfreude and little irony. Those recurring elements work throughout to give structure to that critique; for example, the “blockhead” character in the “Think” panel above also appears as an “empty head”:

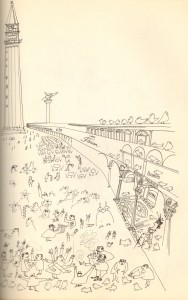

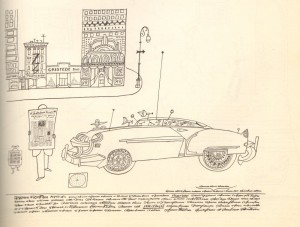

Both signal the manifestation of that self-absorption as lack of wisdom and perspective. This visual trope of emptiness, for example, here appearing on its own, is later combined with other tropes — lavishly decorated urban environments and exotic locales, as well as garish clothing, used to signal the consumptive, conspicuous excess of bourgeois life — to build a representation of the inherent tensions and contradictions of the middle-class routine.

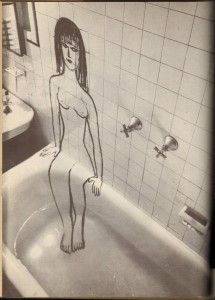

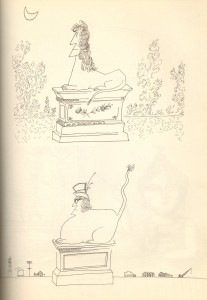

It’s also put together with what passes for “realism” in his scenery as part of his critique of the bourgeois taste for exoticism:

Very few tropes carry only one signification though — the geometric blocked-head also references a “square” character, and when combined with the garish fashions (generally, but not always, for women), signifies a person whose clothes are more expressive than she is. Steinberg’s term “Americanerie” applies here (although his coinage, derived from the French bondieuserie, dates to two decades earlier) but by this volume, he’s entirely cognizant that Americanerie is thoroughly kitsch.

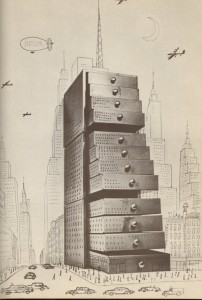

As semiotically rich as it is, though, the book lacks any discernable “narrative arc” – there’s a vague “get the passport, go places” setup in the beginning but it is not sustained for more than a few pages and is tenuous even there. Specific characters rarely reoccur or even congeal into “characters” in the conventional narrative sense, although styles of representing characters, graphical elements recur throughout and form the backbone of the structure. There is an order to the images, but the order itself does not affect the meaning – you could invent a narrative arc for this work, following the order that the images are placed in, but it would be your invention, not Steinberg’s. Steinberg’s order is deliberately, provocatively recursive, and sequence is largely besides the point.

The structure of this book – for it does have structure, just not sequential or serial or narrative structure – is as imaginative and challenging as that found in the prose writing experiments of mid-century, experiments which were beginning, also in New York around the same time, with William Burroughs and the Beats.

Although most lovers of cartoons will express affection for Steinberg, he and his work have been carefully marginalized away from the “center” of comics history. Perhaps the root of the problem is the notion that single-panel cartoons aren’t “comics,” which has always felt specious to me. But there is no question that Steinberg’s experimental sensibility was on par with any literary writer, and the output of his pen is equally important to history. Comics studies and comics theory should definitely have a tent big enough to include him: if for whatever reason it’s important to exclude non-sequential “cartooning” from “comics,” then someone really needs to come up with an umbrella term.

Thanks for reminding me about this book. This was on my “to read” list awhile back, but I never actually got a copy. I’ve seen others mention this in the context of comics/graphic novels, though I can’t now remember where.

It seems like if you did impose a narrative, you’d be really pushing against part of what he’s trying to do — he’s working against travel literature and the idea of travel as a personal journey which can be narrativized….

I entirely agree, Noah.

Derik, you should get yourself a copy as fast as you can! It’s really marvelous.

If you agree though…that opens up a space for Charles to get you. You could argue that it’s consciously eschewing sequence, and is therefore about sequence, thus allowing Charles to keep it as comics while still holding onto the “comics must work with sequence (even if only by negating it)” rule.

I don’t think his definition as written allows for that negative move:

That doubling of “successive in series” just doesn’t describe this book.

I also don’t think that the anti-travelogue “narrative” is powerful enough to be the encapsulation of the entire book. It’s one element of that larger recursive structure, much of which isn’t about sequence at all.

Although I will say that Charles’ definition is the best articulation I’ve read yet of this idea about what comics are.

Well, I think that’s as far as I can play devil’s advocate! If Charles wants to take it further he’ll have to do it himself!

LOL, I think what he said in the original Panelists’ comments thread is pretty good — there’s no doubt that this book is pretty far afield from what most people think of when they think of “comics.”

I’m just looking for a definition that expands the range of experimental possibilities, and Charles is looking for a definition that really gets at the kernel of what comics have meant and still mean to comics readers over time.

What definition has ever expanded the range of possibilities? Contradicting definitions has, of course.

I dunno about that two sphinxes comic. You’ve got the classical one, classic features, great looking decorative flowers, and then the dumpy modern one in the dumpy modern setting, as if to say, life was so much better back when the upper class was REFINED… seems pretty conservative to me.

Charles, I think there are ways of talking about art that have expanded experimental possibilities, although I absolutely take your point that they don’t often look like definitions (neither does what I’ve said about comics) and that the contradictoriness is where the experiment comes in. But I think for experimentalism, it has to be a formal push rather than a materialist one.

Like how Ginsberg talked about poetry or how Delany talked about science fiction, or experimental writing period:

The most experimental position is refusing to allow for any definition at all, I suppose, which is basically your point.

Subdee, I think he’s trying to get at the kitsch there — the way in the ’50s there were all these terrible reproductions of “great European art,” I think it’s not a criticism of modernity because the one on the bottom isn’t actually modern art. It’s not “the old stuff is better than the new stuff”; it’s “the original, appropriate to its time and place is better than the knockoff.” But also a bit about souvenir collecting, and the ways in which travel didn’t quite manage to turn mid-century Americans broad-minded and cosmopolitan — what they brought back, physically and conceptually, was really filtered and Americanized.

At least that’s how I read it…he’s gentle, at least compared with the dominant tone 15 years later, so mileage may vary!

Caro: These are definitely readable and they’re not in sequence: http://dyngraph.free.fr/

But if we’re agreed that definitions don’t expand the range of possibilities, and we’re agreed that expanding the range of possibilities is a good thing — isn’t it maybe not so ideal that comics criticism has been and kind of remains obsessed with definitions?

It just seems like, if as Charles was saying on the other thread — if the social and cultural is the ground for the formal, surely also the formal is to some extent also the ground for the social and cultural. The cultural position of comics and the group of people who read comics creates the boundary for what is formally comics, but the formal limitations of comics also create the cultural position and the group of people who read them. Focusing on sequence and on narrative comics seems like it can have implications for how experimenters are viewed, for what gets thought of as experiments, for where the center is and where the periphery is and who might want to talk about either.

It’s hard to say how much that stuff matters I guess — it’s not like comics artists are necessarily all that influenced by what critics define as comics anyway. But in theory anyway it seems like there’s a question of…is what comics is a culturally defined focus on sequence, with experimenters occasionally moving around the periphery from that more or less stable center? Or is comics a culturally defined space which has various focuses which can shift over time depending on what people do in both the center and the periphery? If you can just dismiss Steinberg as an experiment without having that affect the definition, then there isn’t really any way to move the definition; you just classify things that don’t fit as experiments. In which case the definition is static, and if the definition’s static, aren’t comics static, and is that a good thing?

I don’t necessarily think I agreed that definitions don’t expand the range of possibilities — ossified definitions don’t, but thinking critically about what constitutes some thing is pretty important for experimentation. I think the problem isn’t that criticism is obsessed with definitions so much that it’s obsessed with “definitive” ones. I’m so partial to Delany’s notion of “functional description”…

I think the question of how to move the definition is vital: normally, experimentation IS pulled back into the definition. Experimentation eventually becomes part of the norm. No literary critics anymore would say that novels are defined by linear narrative, although they know that’s still part of what the novel can do or be. Conceptual art (and abstract art and surrealist art, etc. etc.) is widely accepted as part of mainstream visual art culture. Alt and art comics are part of the definition now whereas they wouldn’t have been 25 years ago…I think cartoonists embrace experimentation far more readily than comics critics, but eventually there’s a critical mass of whatever experimentation is going on and the critics catch up. So I don’t think it’s a true stasis situation; I just think that energy has to go into changing it.

On the specific formal issue, I think Charles is trying to say that abstract comics are sequential too, because linear reading and the impulse to linear reading underlie non-linear reading. I think it’s related to your “negative” move above. It’s a very readerly approach.

Except I don’t think it happens here — readerly or formally. I don’t think you start trying to connect Steinberg’s images in sequence and then have the text push back enough that you move into a non-linear mode (which is essentially what happened in Derik’s reading of the Larmee page.) I think instead, here, you read these cartoons individually, as single panels pertaining to a theme, and then as you begin to catch the repeat occurences, that recursive structure emerges.

For a lot of people, (following McCloud I guess?) that makes this not a comic. I think the desire to exclude it is interesting; I think the fact that, historically, it has been excluded is interesting; and I think that trying to craft a definition that does not exclude it but that still captures the other elements of comics that people value and sense and believe in is also interesting — and extremely challenging.

I’m not particularly interested in definitions but one could argue that Steinberg has shifted the definition, possibilities and form of comics through his work.

Steinberg hasn’t been marginalized any more than any other cartoonist of serious intent. He’s influenced contemporary cartoonists (Domingos cites Mazzucchelli), is popular enough that a watercolor “cartoon” from “The Inspector” cost 40-60K (that’s more than a Krazy Kat or Little Nemo btw) and even appears on the TCJ Top 100 Comics list (Charles Hatfield was on that committee). I would say that Steinberg has a pretty big cultural cachet both within and outside comics.

Wouldn’t you say that non-narrative/non-sequential works are deeply unpopular in just about any art form?

Related note: Tom Spurgeon has been promoting Tony Fitzpatrick’s “The Wonder” as a great comic book and he hasn’t made much headway there as well.

Non-narrative, non-sequential works aren’t always unpopular necessarily, depending on what you mean exactly by the terms. Any instrumental music track is going to be non narrative, and sequence doesn’t exactly fit there. Jackson Pollack is a household name, anyway, and his work isn’t narrative or sequential…. Architecture isn’t narrative or sequential ever… Videos can be really non-sequential and weird — and this is bizarre. It seems like it really depends on what folks expect or are looking for or are used to….

Noah: Obviously I meant within largely narrative forms – so movies, theater, opera and novels. I would say that Steinberg (re: comics) is as big as Stan Brakhage (re: film), and probably much more popular.

Caro: Not really a McCloud-UC apologist but…McCloud would probably consider something like “The Passport” a comic. There’s almost no doubt that he would consider “Magic Forest” a comic. It fits like a glove into his “moment-to-moment” transition category (as would “The Passport”). A single line drawing (like the first one on this page) stuck on a wall probably wouldn’t fit his vision, not that this really matters of course.

Sure…but whether comics should or has to be defined as a largely narrative form is kind of the question….

Yes, but I’m not saying it’s definitional. I’m merely pointing to the facts on the ground, that narrative forms dominate literature, movies and comics. There’s nothing particularly strange about the situation in comics. There are quite a number of non-narrative comics out there, they just don’t have large print runs. Andrei listed a whole bunch of them a few months back. A Brakhage DVD probably sells in the low thousands for all we know. The avant garde cartoonists out there don’t give a hoot about McCloud, Groensteen or RC Harvey’s theories. So I fully support your “I know it when I see it” definition of comics (or Caro-Delany’s “functional definition” if you prefer something more systematic yet flexible).

Suat, I largely agree with what you’re saying — especially the limited popularity of non-narrative, non-sequential art in all media. I think it is the peculiar emphasis on narrower-than-necessary definitions, among both fans and critics (although not artists), that’s the strange situation in comics. Given how much variety there is on the ground, as you rightly point out, it’s hard to account for the prevalence of “Sequential Art”-oriented definitions of and approaches to comics, even in academia and art criticism…

In film, both the reality/practice and the definition/concept encompass everybody from Brackage and Cocteau to Lynch and Spielberg. But I have actually had people tell me face-to-face that Anke Feuchtenberger is “not comics” when I name her as a favorite. And that Steinberg is a cartoonist, “not really comics” despite his unarguable influence. There’s just not a terribly flexible and inclusive understanding of what comics means.

There’s a tendency instead to talk about the art form in these exclusive, definition-oriented ways. It’s the strength and pervasiveness of that impulse to define the form in a narrow, highly specific way — often competing highly specific ways — that seems to me to be different in comics than the other arts.

Of course there are lots of people who wouldn’t agree with those assessments of what’s comics and what’s not and there are plenty of people who eschew definitions and would embrace not only the Steinberg but even my Rauschenberg and Pollock examples and the “functional definition” they invite. But I think there’s not consensus even among fans of art comics, and I imagine if we opened up the debate to include the larger genre-loving majority, even more would side against this more liberal definition.

(I don’t think anybody anywhere except a willful curmudgeon would say that Steinberg isn’t a cartoonist, though, or that cartooning hasn’t been influential on comics.)

I guess — an emphasis on sequence in the definitions to me makes comics into a “genre” rather than a medium (just like “narrative film” is a genre). But that begs the question — a genre of what? Literature? Visual art? It’s both — which is why there’s this inclination now to think of it as a medium…and so I think there is a need to theorize the medium in ways that don’t reduce it back to a genre. That’s the ill-fit: in practice, comics has broken out of genre boundaries and become a medium. But in theory, comics are still thought of in very genre-laced terms…

Caro, here’s review of Steingberg’s fine sort-of autobiography I wrote for the Journal in ’04, and a story:

I discovered Steinberg in this bookshop beneath a strip mall. It had The Passport and The Inspector, so I played the used-bookstore game of going back to check on them until I could afford them. They’re in those used-bookstore clear plastic dustcovers. And no one else in Lexington had the same taste, so I got them all.

The man who ran the store had to, because when he retired from IBM he drove his wife crazy pottering about. He also had too many books, so: used bookstore. I had a girlfriend whose allergies prevented her from entering the store– her face puffed up after three minutes on her only visit– so whenever I went it was like a literary locker room by default. We’d chat about graphic design & Proust out of the summer heat. Then he died suddenly of a heart attack, the store closed and his wife moved to Florida.

I still haven’t read Proust.

Steinberg’s books are really special, and I enjoyed your piece. The Passport is so cohesive; I can’t imagine the worth of any definition that doesn’t include it. Amanda Vähämäki & Michelangeo Setola’s “Souvlaki Circus” is similarly a cohesive comic without a narrative or characters, and no text to drag it down. I’m trying to think of some others, but blanking for now…

I think I’d have to see a whole book of his stuff before deciding whether he really has a thing against – not modern art – but modern life. I specifically mean those little track houses and the oil rig and billboard in the background, so crass next to the foliage on the top panel… although maybe you are right, and this is Steinberg saying that any great art brought into such an empty and culture-less country is going to turn into something totally different and much more pedestrian.

I just finished reading V. S. Naipul’s Guerrillas, so I was primed think about people whose view of the present is that is decaying, because they are holding onto some glorious aristocratic past. The little guys carrying stamps around seems like it could also be a dig against modern (fifties) office culture.

Bill: “I still haven’t read Proust.”

What are you waiting for, Bill? If I had to describe Proust I would say: imagine an insight machine capable of producing an insight per sentence and doing that for 3.000 pages. With an average of 10 insights per page it’s 30.000 insights. I’m clearly exaggerating, but you get the idea… I particularly like Swann’s love affair. Only Sapho comes to mind as someone capable of describing jealousy this well. Plus: Proust was a master in describing little nuances in class taste, class behaviour, etc…

As for the discussion at hand, this is what I have to say: http://tinyurl.com/6fnxmug

There’s also a coda: http://tinyurl.com/634naq8

I’d say there’s a certain celebration of brash America there. I think one can make a parallel with Nabokov’s ‘Lolita’ in that respect…

One more thing: I first heard about Saul Steinberg in Peter Kuper’s house. There’s another comics connection, right there.

The most experimental position is refusing to allow for any definition at all, I suppose, which is basically your point.

No, any experiment unaware of the extant order is just as likely (probably more so) to reinvent the wheel as those who slavishly follow the design.

I don’t necessarily think I agreed that definitions don’t expand the range of possibilities — ossified definitions don’t, but thinking critically about what constitutes some thing is pretty important for experimentation. I think the problem isn’t that criticism is obsessed with definitions so much that it’s obsessed with “definitive” ones. I’m so partial to Delany’s notion of “functional description”…

A functional description is going to be concerned with what has worked and hasn’t worked, so Delany’s going to have something like a conceptual prototype (for definitions, he’d definitely call X a comic; in evaluation, he’d say Y is good literature). From that you can either be closed off to changes made to it, or (as Delany is) open to them.

But not having a definition doesn’t have anything to do with being aware or unaware of the extant order. Most people don’t spend a whole lot of time trying to define “film”, but they still know a film when they see one. If you’re doing math, obviously, rigorous definitions are essential. But (as I’ve said before), art isn’t math, and rules of thumb seem like they’d be at least as useful (or actually more useful) in most circumstances.

I wouldn’t call a conceptual prototype a definition, is perhaps where we’re differing. (i.e.; we’re squabbling over the definition of definition. Can’t get more meta than that!)

But not having a definition doesn’t have anything to do with being aware or unaware of the extant order.

Sure it does. A definition, however formalized, is an attempt to capture what concept or family of concepts people are using when they apply a term. If a person is to make any sense to others, then he or she is working within or against some order of things.

By ‘prototype’ I meant an example (token) that could serve as a prime example of the definition (type), thereby giving weight to the definition (sort of like gravity).

Nah, still doesn’t. You don’t need to attempt to capture the concept in order to have a grasp on the concept. You don’t need to have a definition in order to make sense to others (again, unless you’re working in a formally rigorous system like math.)

People work with ad hoc concepts, not rigorous definitions, for almost everything they talk about. You can have a prototype without a definition. And in fact, instead of the prototype giving weight to the definition, the definition can obscure the prototype.

Noah:

“But not having a definition doesn’t have anything to do with being aware or unaware of the extant order. Most people don’t spend a whole lot of time trying to define “film”, but they still know a film when they see one. If you’re doing math, obviously, rigorous definitions are essential. But (as I’ve said before), art isn’t math, and rules of thumb seem like they’d be at least as useful (or actually more useful) in most circumstances.”

Amen!

The weird tyranny of math in today’s society ignores this truth. Everything must be measurable to an ins

Fucking stupid software!

Everything must be measurable to an insane degree, even such imprecise values as intelligence or beauty. We live in a society of robotic Francis Galtons.

In real life, even in domains such as business, we reason not in mathematical terms, but in quantitative ones.

I don’t say that I have 14% excess stock, I say simply that I have too much stock; I don’t think that it’s 3.5 days until optimum launch of winter sales, I think it’s just too soon.

Noah, you’re not making any sense. Unless you have some inkling of how people tend use a term, how would you go about defining the term? Privately? “Tend to use a term” entails an order of some sort.

Of course, people who aren’t attempting to give an explicit definition of a term don’t necessarily have one waiting to be used. I didn’t think we were talking about them. If you’re going to define something, then you have to take such implicit definitions as used in practice into account.

“Tend to use a term” entails an order. That order doesn’t need to be a definition.

As an example; a definition tends to be a formal statement. The way people tend to use a term can involve lots of social and cultural cues that don’t easily reduce to a sentence or a paragraph description.

I’m arguing that in the case of aesthetics, those vague social and cultural (and formal) cues are consequentially more useful and accurate than a formal definition can be.

Art is definitely one realm where you don’t need to know what you’re talking about.

Defining art is the attempt to nail down those vague social and cognitive cues that people use when talking about and creating art. Is it always useful? Of course not.

When the flush of a new-born sun fell first on Eden’s green and gold,

Our father Adam sat under the Tree and scratched with a stick in the mould;

And the first rude sketch that the world had seen was joy to his mighty heart,

Till the Devil whispered behind the leaves, “It’s pretty, but is it Art?”

Wherefore he called to his wife, and fled to fashion his work anew —

The first of his race who cared a fig for the first, most dread review;

And he left his lore to the use of his sons — and that was a glorious gain

When the Devil chuckled “Is it Art?” in the ear of the branded Cain.

They builded a tower to shiver the sky and wrench the stars apart,

Till the Devil grunted behind the bricks: “It’s striking, but is it Art?”

The stone was dropped at the quarry-side and the idle derrick swung,

While each man talked of the aims of Art, and each in an alien tongue.

They fought and they talked in the North and the South, they talked and they fought in the West,

Till the waters rose on the pitiful land, and the poor Red Clay had rest —

Had rest till that dank blank-canvas dawn when the Dove was preened to start,

And the Devil bubbled below the keel: “It’s human, but is it Art?”

The tale is as old as the Eden Tree — and new as the new-cut tooth —

For each man knows ere his lip-thatch grows he is master of Art and Truth;

And each man hears as the twilight nears, to the beat of his dying heart,

The Devil drum on the darkened pane: “You did it, but was it Art?”

We have learned to whittle the Eden Tree to the shape of a surplice-peg,

We have learned to bottle our parents twain in the yelk of an addled egg,

We know that the tail must wag the dog, for the horse is drawn by the cart;

But the Devil whoops, as he whooped of old: “It’s clever, but is it Art?”

When the flicker of London sun falls faint on the Club-room’s green and gold,

The sons of Adam sit them down and scratch with their pens in the mould —

They scratch with their pens in the mould of their graves, and the ink and the anguish start,

For the Devil mutters behind the leaves: “It’s pretty, but is it Art?”

Now, if we could win to the Eden Tree where the Four Great Rivers flow,

And the Wreath of Eve is red on the turf as she left it long ago,

And if we could come when the sentry slept and softly scurry through,

By the favour of God we might know as much — as our father Adam knew!

–Rudyard Kipling

IN THE Neolithic Age savage warfare did I wage

For food and fame and woolly horses’ pelt.

I was singer to my clan in that dim, red Dawn of Man,

And I sang of all we fought and feared and felt.

Yea, I sang as now I sing, when the Prehistoric spring

Made the piled Biscayan ice-pack split and shove;

And the troll and gnome and dwerg, and the Gods of Cliff and Berg

Were about me and beneath me and above.

But a rival, of Solutre, told the tribe my style was outre-

‘Neath a tomahawk, of diorite, he fell

And I left my views on Art, barbed and tanged, below the heart

Of a mammothistic etcher at Grenelle.

Then I stripped them, scalp from skull, and my hunting-dogs fed full,

And their teeth I threaded neatly on a thong;

And I wiped my mouth and said, “It is well that they are dead,

For I know my work is right and theirs was wrong.”

But my Totem saw the shame; from his ridgepole-shrine he came,

And he told me in a vision of the night: –

“There are nine and sixty ways of constructing tribal lays,

“And every single one of them is right!”

* * * *

Then the silence closed upon me till They put new clothing on me

Of whiter, weaker flesh and bone more frail;

. And I stepped beneath Time’s finger, once again a tribal singer,

And a minor poet certified by Traill!

Still they skirmish to and fro, men my messmates on the snow

When we headed off the aurochs turn for turn;

When the rich Allobrogenses never kept amanuenses,

And our only plots were piled in lakes at Berne.

Still a cultured Christian age sees us scuffle, squeak, and rage,

Still we pinch and slap and jabber, scratch and dirk;

Still we let our business slide-as we dropped the half-dressed hide-

To show a fellow-savage how to work.

Still the world is wondrous large,-seven seas from marge to marge-

And it holds a vast of various kinds of man;

And the wildest dreams of Kew are the facts of Khatmandhu

And the crimes of Clapham chaste in Martaban.

Here’s my wisdom for your use, as I learned it when the moose

And the reindeer roamed where Paris roars to-night:-

“There are nine and sixty ways of constructing tribal lays,

“And-every-single-one-of-them-is-right!”

Domingos, that’s a hell of a fine blurb. I know I should read it, it’s staring me down from my bookshelf. But I’m still too lost in wanton dissipation to focus on much more than a Cesar Aira novella…

And Aira wrote a monograph on the Argentine cartoonist Copi. There’s yet another comics connection, right there.

Pingback: Di Saul Steinberg « Guardare e leggere

comment sapelle le premier dessin ?

quel est le nom du premier celui qui attend

comment sapelle le prmier celui qui attend ou sennui

Pingback: It’s Monday what are you reading and Nonfiction Monday: Marcus, Juster, Steinberg, Willems | Gathering Books