This is an exploration of how Kouga’s inks and composition show character and mood in the first volume of Loveless. The art style shifts with point of view and interactions, building into a powerful visual language.

I have mixed feelings about Loveless. It’s a hot mess in a lot of ways. The story contains horrible child abuse of various kinds, including some that is institutionalized and some that is family, various reprehensible relationships, some seriously broken people, a couple of sociopaths, BDSM themes (both consensual and not), dubious portayals of motives of people who ought to be villains but might not be, amnesia, innapropriate information about sexuality, and some of the most heartbreaking and beautiful characters I’ve ever read.

All this in a cat boy story about preteens. Oh, manga.

In the world of Loveless, everyone has cat ears and cat tails. They lose them when they have sex, consensual or not, so you can tell the virgins by their ears.

Ritsuka, the main character, has lost his memory of the last two years under some kind of trauma involving his older brother’s murder. He’s entering a new school, after some mysterious and upsetting thing happened at his last school. We meet him on the first day at his new school.

Despite his young age and his helpless position in society, Kouga portrays Ritsuka as wise and thoughtful, if full of self-hatred. She introduces Ritsuka with clear, simple inks. Against the chaos of a new school, Ritsuka is stark and straightforward, heavier lines in his outline and smoothly positioned in the frame:

Ristuka hates lies. He’s very grounded in the world and he’s painfully present. His portrayal in the inks changes when he feels different emotions, as we’ll see, and when other people view him. But overall, he is portrayed with smooth, dark, clear inks and a classic, unobtrusive style as a default.

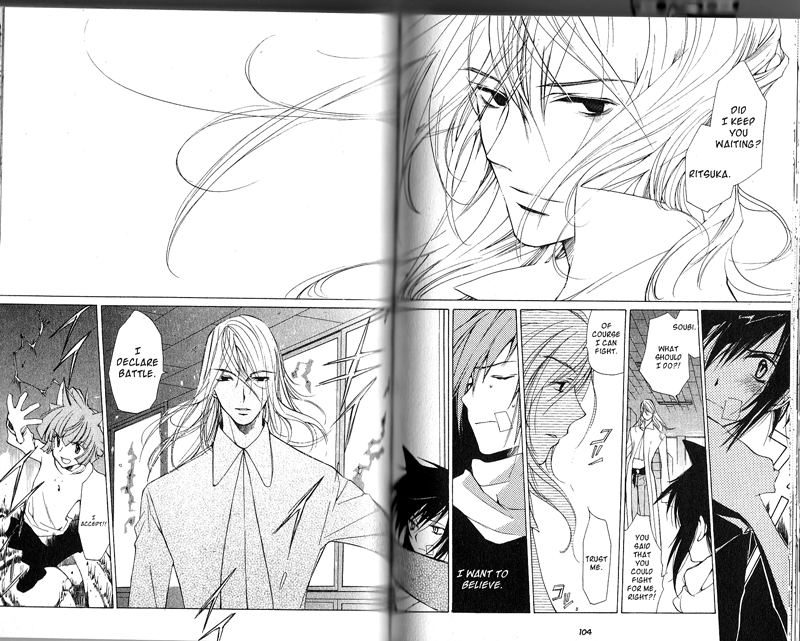

The next major character is Soubi, who belonged to Ritsuka’s older brother and who was given to Ritsuka in his will. Soubi is a ‘fighter’, one half of a mystical pair that make up a name. Soubi is a difficult character–much older than Ritsuka, just as broken, and very troubled. Here is his introduction:

As you can see, Soubi’s body is elongated, warped, somewhat strange, but beautiful in an abstract way. He wears bandages around his throat. He’s literally one of the walking wounded. As the story progresses, we find out that Soubi has been stretched, molded, broken into being something specific. There is a constant tension in the story between what other people want to make Soubi into and what Soubi tries to be. See Soubi’s hair at the top? It’s waving and a bit wild, and smoothes down in the second panel. Keep an eye on the hair.

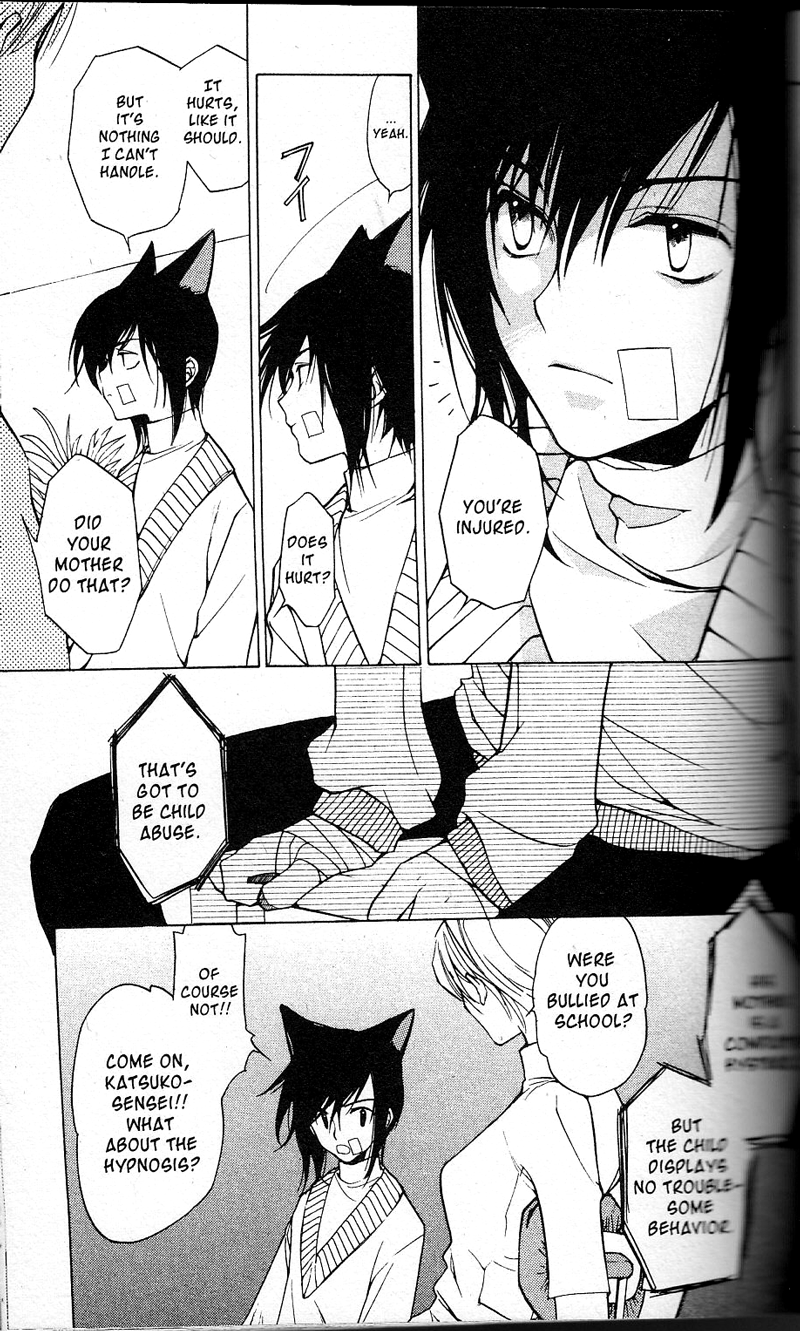

Here’s another scene with Ristuka, this one with his therapist. Here we see Ritsuka has bandages on his face and hands–he is visually tied back to Soubi by their mutual wounds. Ritsuka has been hurt by his mother, who beats him. Like the first picture of him, in this page Ritsuka is firmly in the frame, situated in the environment, and drawn with smooth, straightforward inks.

Compare that to this picture of Soubi:

Soubi is completely disconnected from any environment, and his hair is beautiful chaos, spreading out in tendrils. This is where Soubi begins to drag Ritsuka into the fantasy world of fighters. It’s a world where Soubi is very competent (as a fighter) but especially broken emotionally. His hair tends to be portrayed in ways that are otherworldy and wild, and he sometimes becomes more distorted. The jagged shapes in the panels below help portray confusion. Soubi is drawn very lightly, without the weighted lines that Ristuka has above.

Soubi is completely disconnected from any environment, and his hair is beautiful chaos, spreading out in tendrils. This is where Soubi begins to drag Ritsuka into the fantasy world of fighters. It’s a world where Soubi is very competent (as a fighter) but especially broken emotionally. His hair tends to be portrayed in ways that are otherworldy and wild, and he sometimes becomes more distorted. The jagged shapes in the panels below help portray confusion. Soubi is drawn very lightly, without the weighted lines that Ristuka has above.

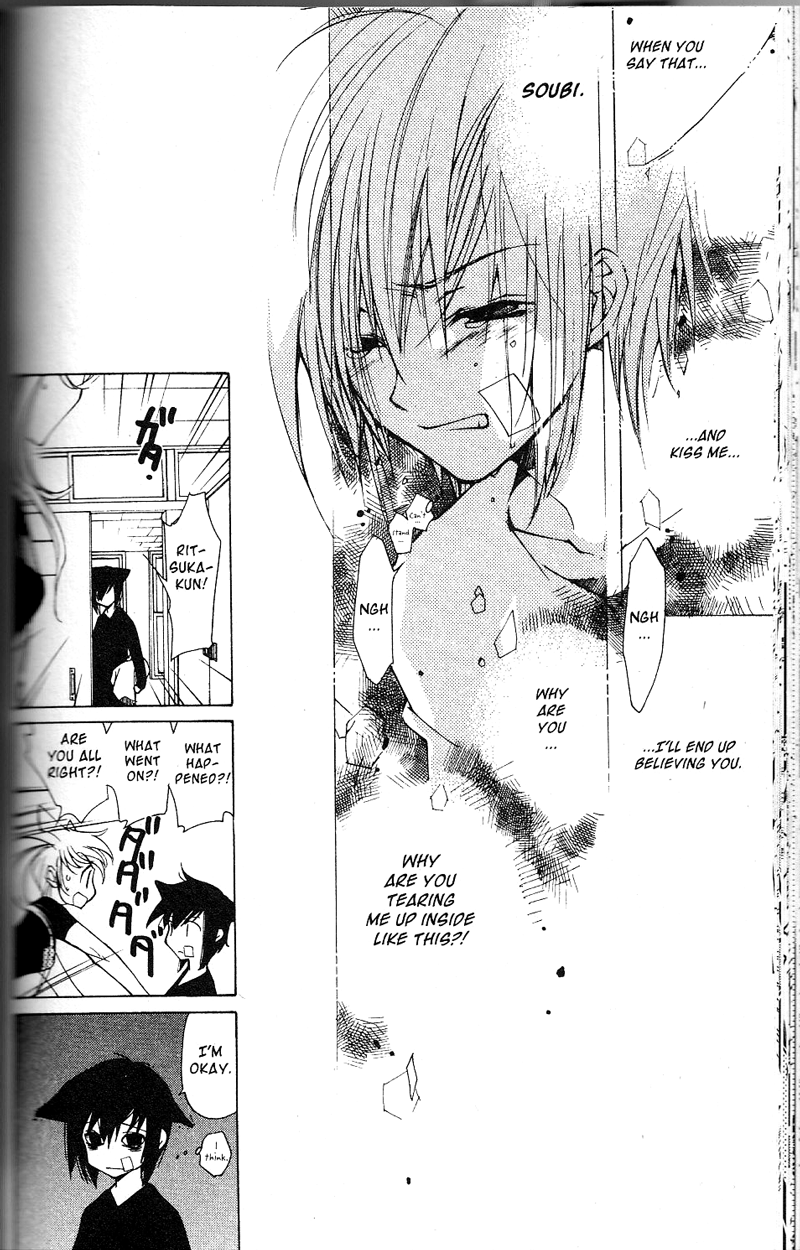

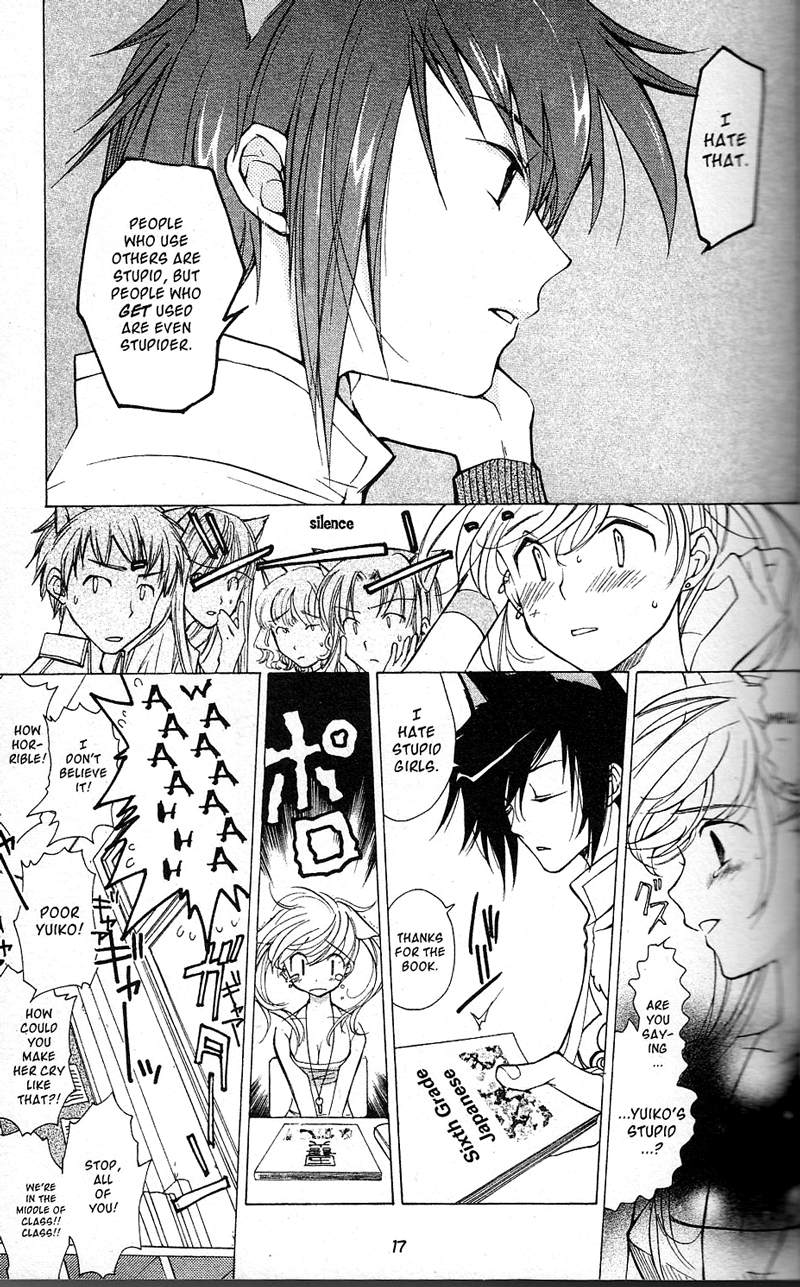

One of the most painful, but most effective and beautiful, parts of this manga is the visual portrayal of the characters effects on one another. Above is Ritsuka, practically shattered by tones and ink, shaking, thinking about how he feels when Soubi says he loves him. Ristuka in the lower left panels is now tiny but even more heavily inked than before–he’s becoming more real. The lines of strain are still there on his chibi-like figure, but he’s very grounded in the space, the door is present, the hallway, his friend Yuko, he’s real.

One of the most painful, but most effective and beautiful, parts of this manga is the visual portrayal of the characters effects on one another. Above is Ritsuka, practically shattered by tones and ink, shaking, thinking about how he feels when Soubi says he loves him. Ristuka in the lower left panels is now tiny but even more heavily inked than before–he’s becoming more real. The lines of strain are still there on his chibi-like figure, but he’s very grounded in the space, the door is present, the hallway, his friend Yuko, he’s real.

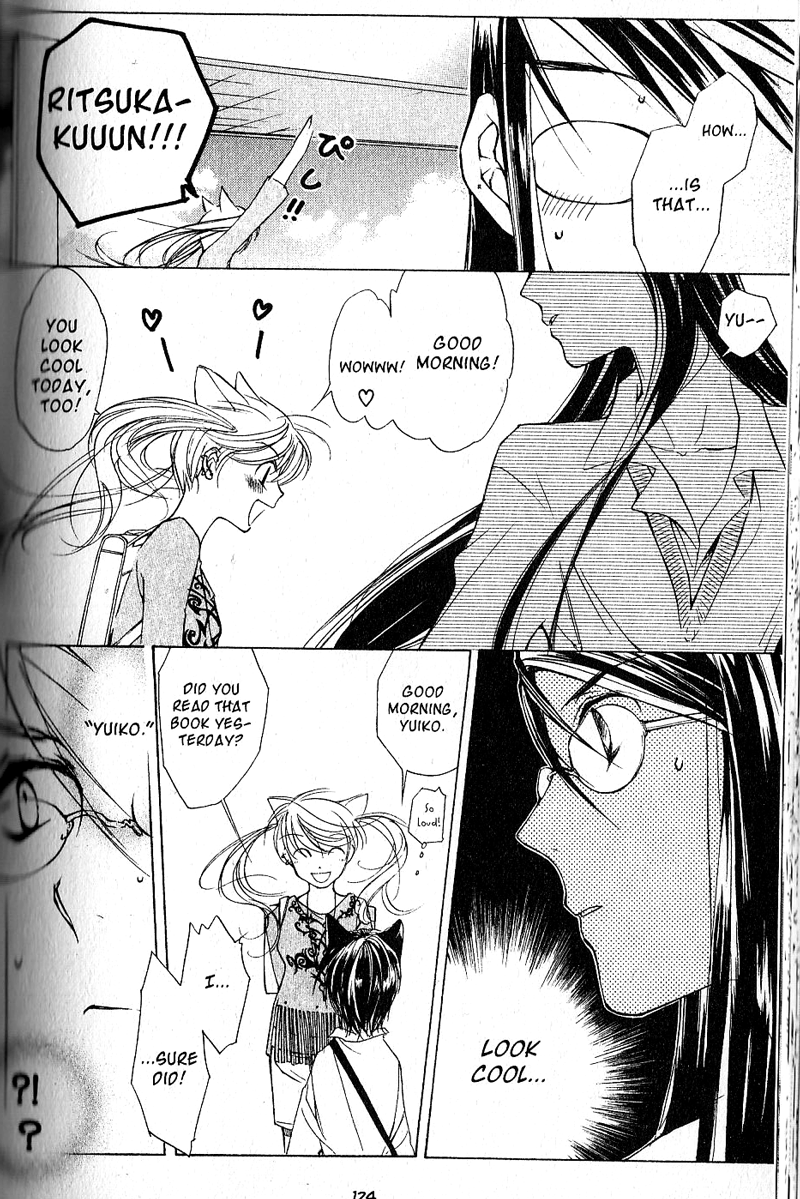

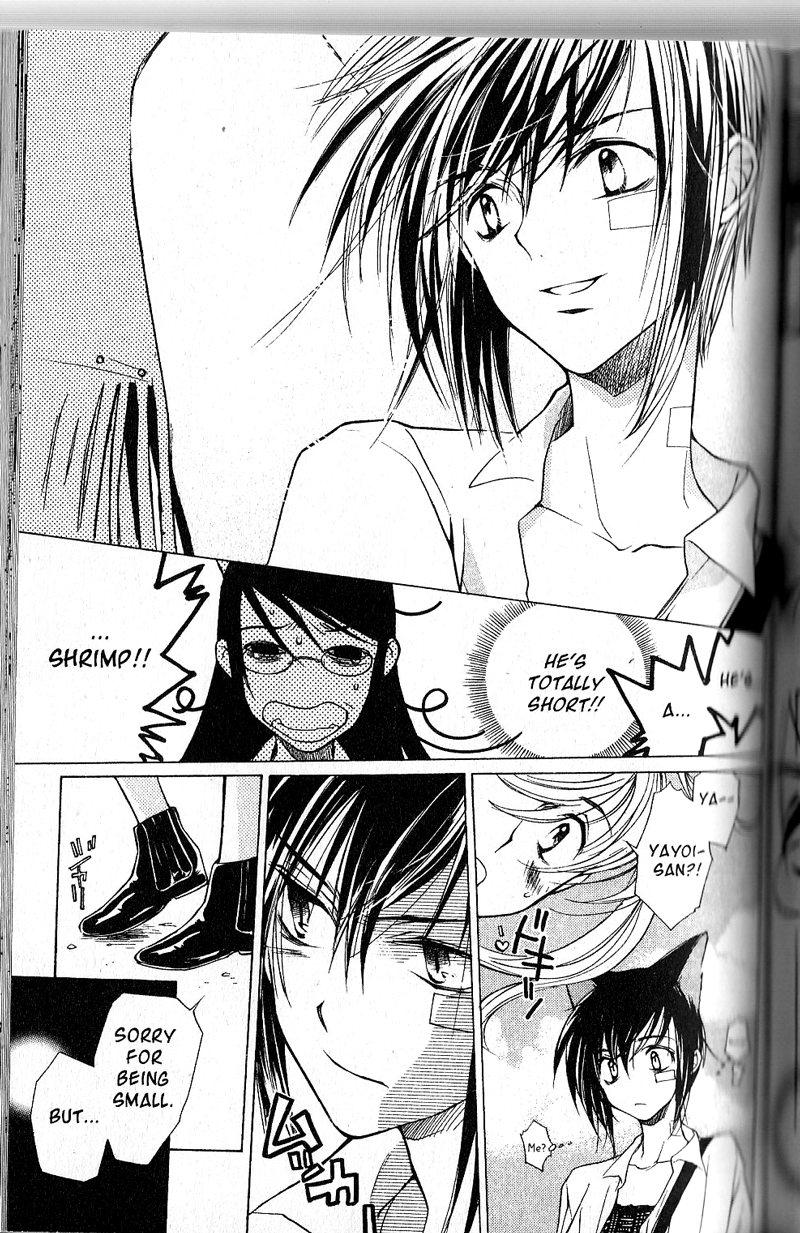

But Loveless is not a meet Ritsuka and become happy love fest. (Ahahaha, yeah, no.) Here’s another portrayal of Ritsuka, this time from Yuko’s friend (who has a crush on Yuko):

See how we’re on his eye glasses and stripey hair, that clues us into the viewpoint, and then we focus on Ritsuka, who….

See how we’re on his eye glasses and stripey hair, that clues us into the viewpoint, and then we focus on Ritsuka, who…. suddenly has stripey rockstar hair. Isn’t that hilarious? I love it. And Yuiko’s buddy Yayoi is so put out and jealous. I love it. Kouga doesn’t just use this style-change technique with Yayoi (so far he’s a pretty minor character). Let’s look at Soubi’s best friend, Kio.

suddenly has stripey rockstar hair. Isn’t that hilarious? I love it. And Yuiko’s buddy Yayoi is so put out and jealous. I love it. Kouga doesn’t just use this style-change technique with Yayoi (so far he’s a pretty minor character). Let’s look at Soubi’s best friend, Kio.

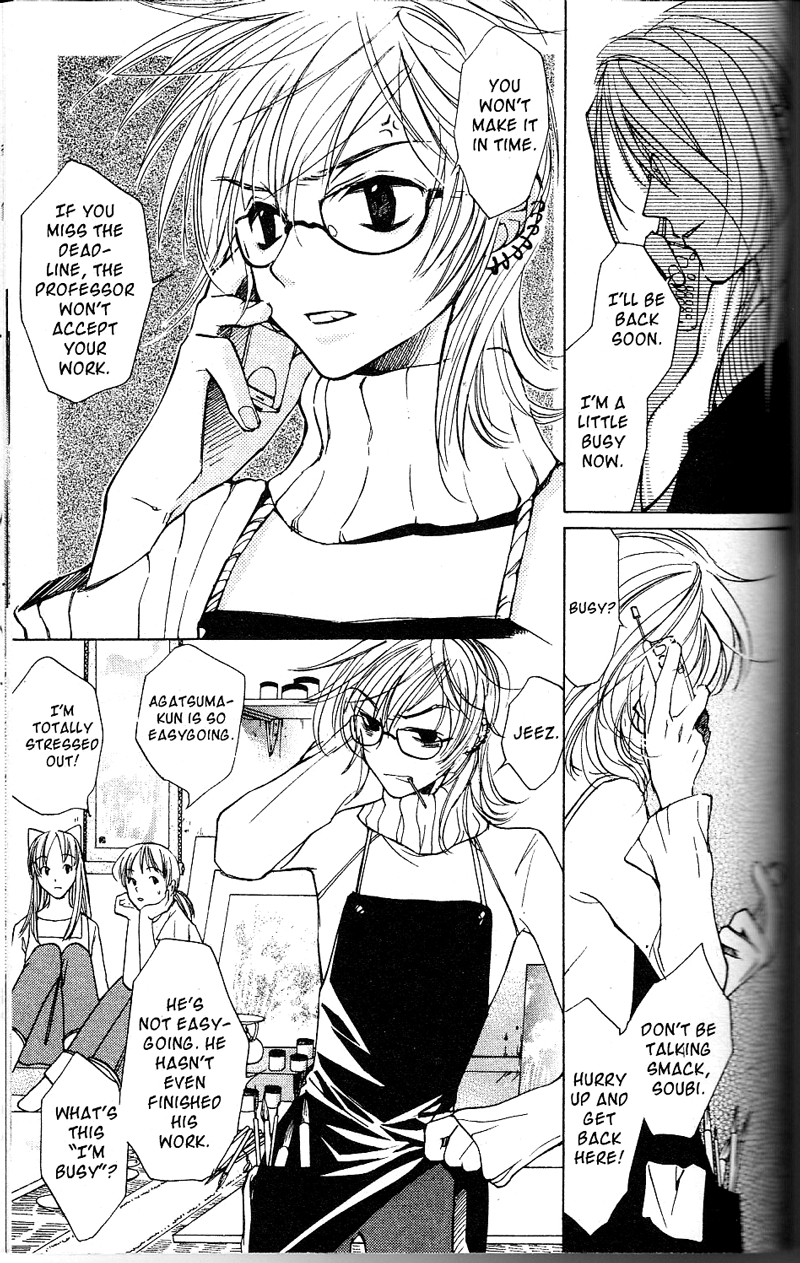

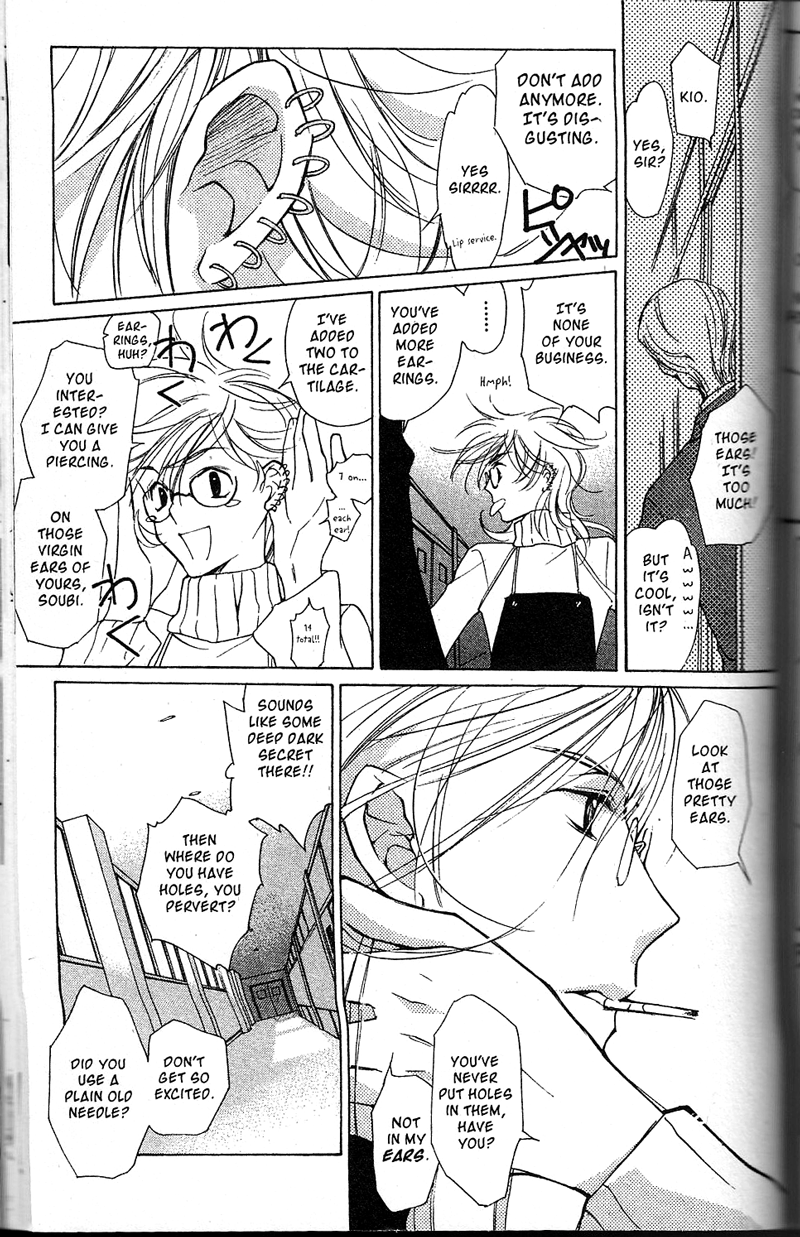

Unlike Soubi, Ritsuka, and practically everyone else in the whole manga, Kio is fairly healthy. He claims to be a bit of a pervert, but he’s mostly practical, warm, upbeat, and happy. His art depiction is light, joyful, playful. He’s an art student and he favors stylish clothes and earrings, but he often gives Soubi sensible advice and he’s something of a voice of reason in the manga. Caring, thoughtful, and kind.

The panel is very grounded, with some of the same dark-line in the body lines that grounds Ritsuka, but it’s also airy and open, with fluffy lines creating a lot of movement around him.

The panel is very grounded, with some of the same dark-line in the body lines that grounds Ritsuka, but it’s also airy and open, with fluffy lines creating a lot of movement around him.

Like other characters above, when he interacts with Soubi, Soubi reacts, and the art changes.

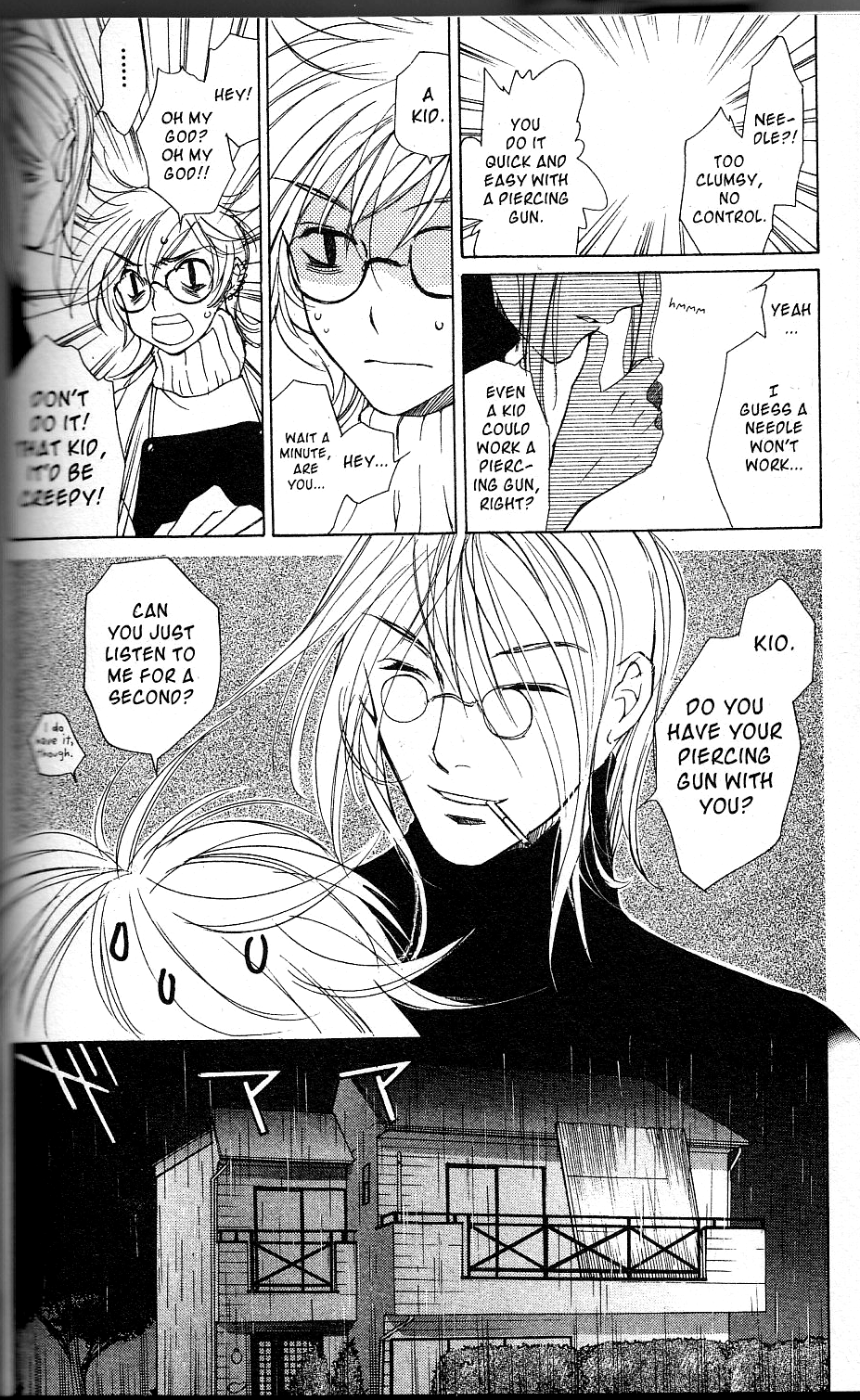

These two pages are a discussion between Soubi and Kio, where Kio shows off his earrings, tries to talk sense into Soubi, and Soubi reacts. You can see that Soubi’s hair is reflects a more Kio look as the panels progress. Here, Soubi has the standard Soubi hair.

Here, at the very last panel, Soubi’s hair has a perky fluff to it.

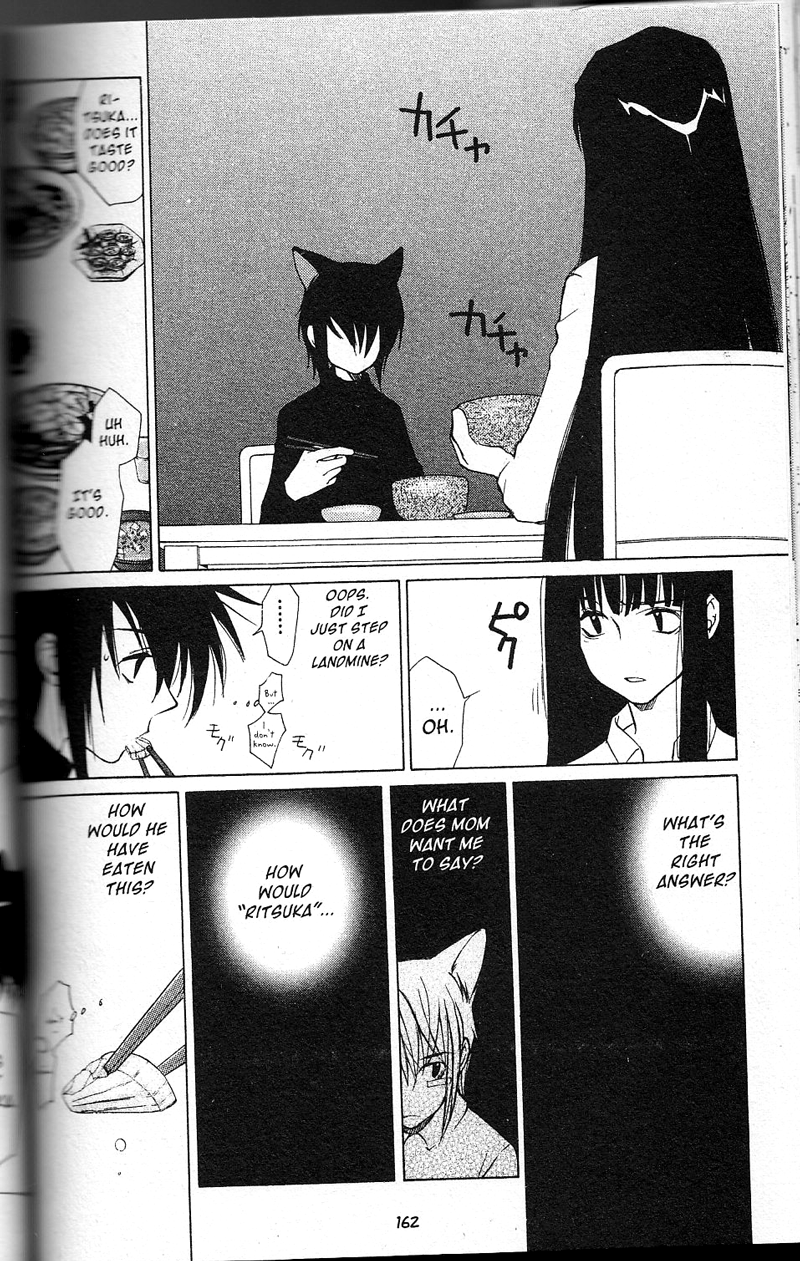

While Soubi is getting ideas, Ritsuka’s mother, who abuses Ritsuka and is crazy, has a very dark, black and white view of the world:

In the top panel, Ritsuka doesn’t even have a face. Her view is black over everything–nothingness and horrible blankness. It’s a viewpoint that Kouga returns to in later volumes as well, and is both effective and at times difficult to read.

In the top panel, Ritsuka doesn’t even have a face. Her view is black over everything–nothingness and horrible blankness. It’s a viewpoint that Kouga returns to in later volumes as well, and is both effective and at times difficult to read.

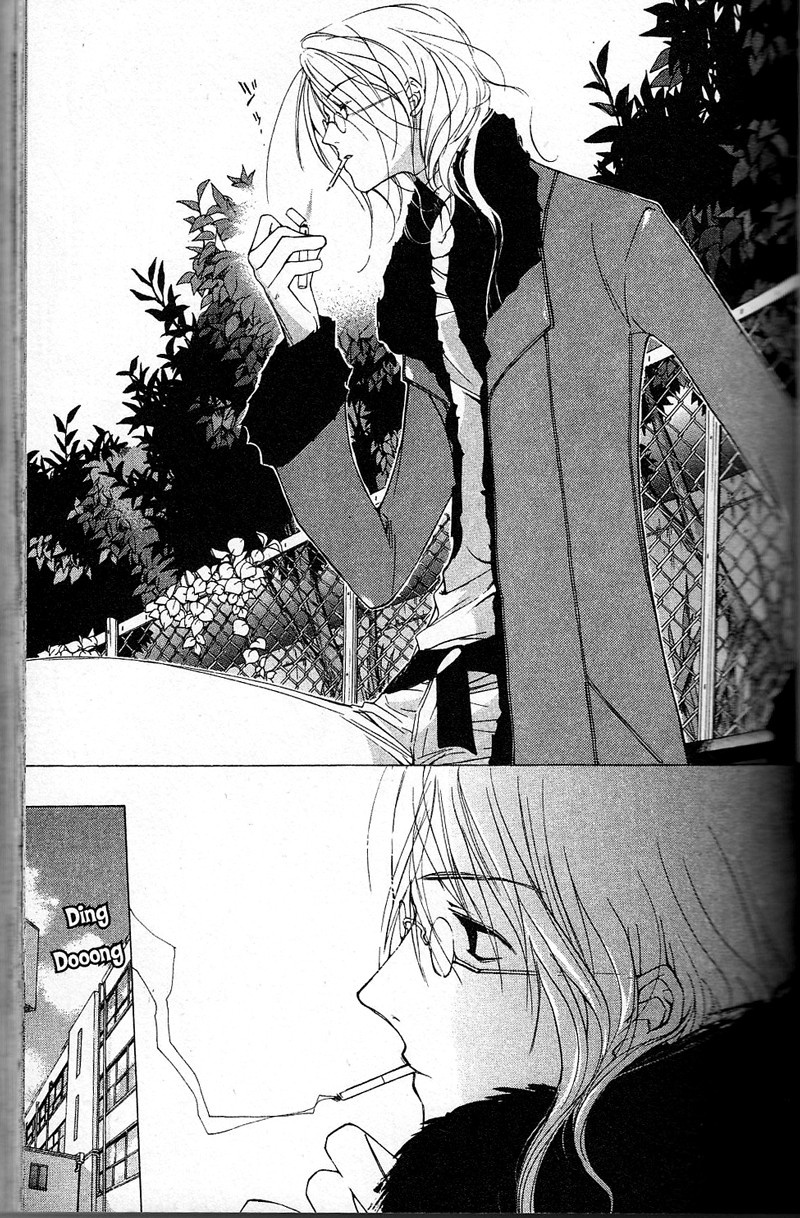

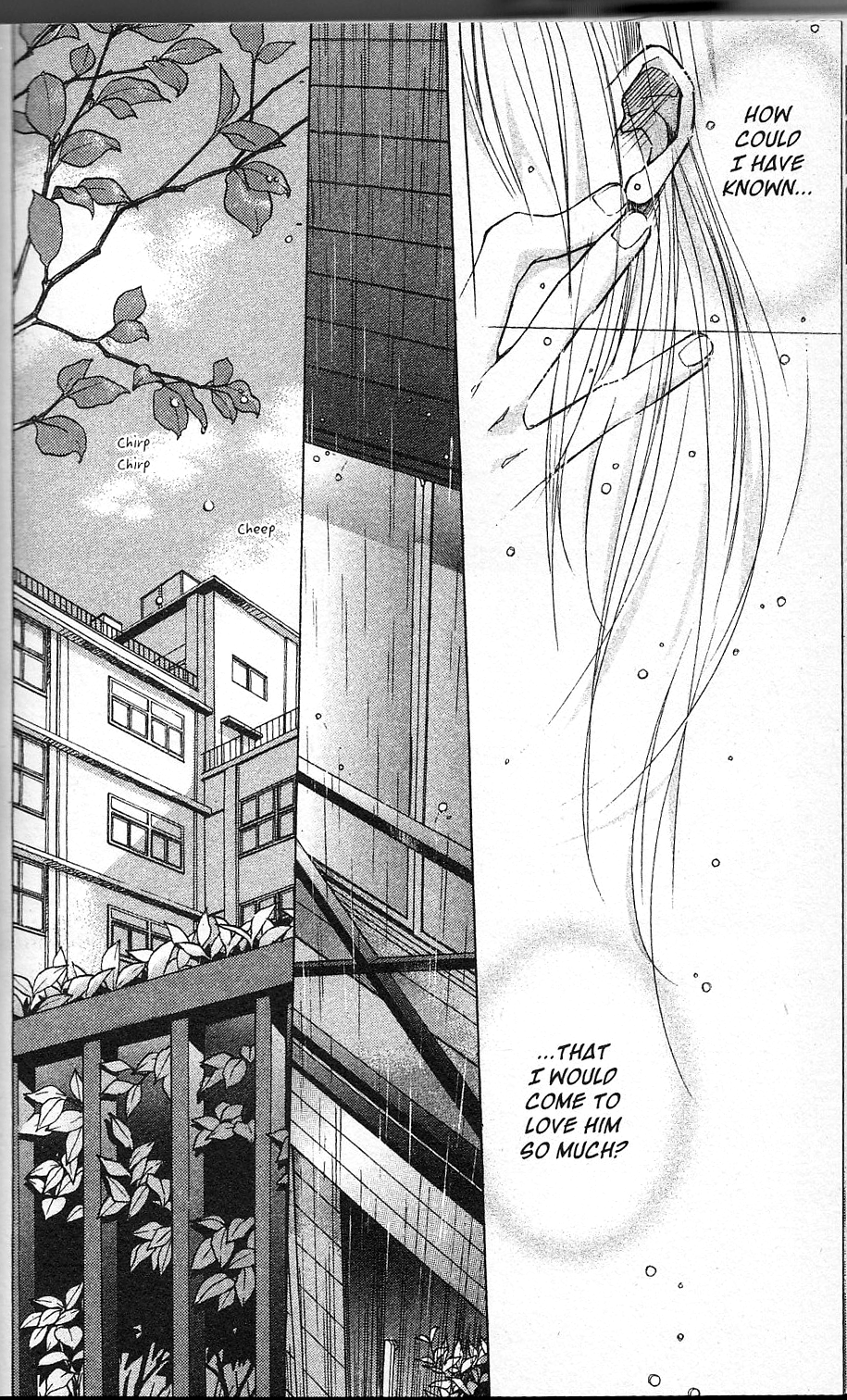

I’m going to end with a page that sums up what I think is the visual language that Kouga is building. Soubi and Ritsuka have just talked, and Ritsuka has pierced Soubi’s ear with Kio’s earring gun to mark him. It’s a link they now have, Ritsuka and Soubi against the world. (I told you the manga was problematic.) For Soubi, it is a move from a dark and ugly existence towards one that is cleaner. This last page shows that theme. We get a shot of their tie, the earring, and Soubi’s hair. Unlike earlier times, Soubi isn’t distorted; his ear is realistic and lovely, his hand not pulled out of shape. The hair strands echo the smooth, soft movement the story has taken–it’s calmer, too. The page shifts from Soubi’s hair to the rain, washing down from the sky, very natural and supposedly dark, to the next panel, which shows a new day, clean and bright, with spring greenery and bird song.

Loveless!!!

This is a great essay. Thank you so much for pointing out the way the art style shifts to reflect character POV, this is one of the things that subtly affects your understanding of the story, but is less obvious (at least to a verbally oriented person like me) than the characters’ own exposition of the story’s themes.

About Loveless being problematic: I think this is actually addressed as the story goes on. Have you read Yun Kouga’s other famous work, Earthian? Earthian also has parent-child abuse themes, but they are secondary to and in some ways equated with the forbidden homosexual love themes.

…Basically, Earthian starts out with a status quo and then you find out that it’s wrong and evil and messed up and you should break the rules and act transgressively. Chihaya ends up defending his homosexual love in court and the Angels’ “point” system is revealed to be a totally self-interested charade. Plus, Chihaya is discriminated against because he has dark hair, which readers (esp. in Japan) can recognize is totally arbitrary. So then he manga is about realizing that the system you grew up with isn’t perfect and might not even be right. The solution is to throw off the shackles of your oppressive society.

Loveless, on the other hand, starts out really transgressively – BDSM themes, incest themes, shota themes, cat boys, child abuse, you name it. But the story goes in the opposite direction: Ritsuka believes in loving people no matter what, but the manga kind of questions whether that’s really a good idea – whether there are circumstances under which you should NOT love other people, when they are only going to hurt you. Also, Soubi in the beginning seems to be okay with being messed up, but you find out eventually that it’s not really okay for him to be that way.

In short this is a deep manga, and the dark themes are not just there to appeal to the readers’ prurient sensibilities. Although there is some of that too. ^^ The BDSM shota catboy angle /totally/ makes it onto the covers, which makes Loveless kind of a difficult manga to buy at the bookstore. But, you know, got to hook the readers in somehow.

I’m so glad you enjoyed it subdee! I love watching the way the inks change from character to character–Kouga is such a powerful storyteller.

I admit I couldn’t get into Earthian, but that was years and years ago. I had a harder time with her style of art back then.

That’s a great point about the two series going in different directions, transgressively. I have read the later volumes of Loveless. I think the power of the story is how you say, that Soubi slowly realizes it’s not how he was supposed to be, and that Ritsuka loves blindly, and how dangerous that is. What I’m worried about is whether the wounds that Soubi carries won’t turn to be what wins the battle with SekritVillain (in case anyone who hasn’t read up to the most recent stuff is reading). If that’s what happens, I think it might push the weight of the story too far into saying that what Soubi’s trainer did was justified. That this is the way to make the ultimate fighter. But OTOH, I don’t know, I want Soubi to win and to have overcome his trauma.

But mostly I just miss Loveless. *sigh* I wish it would come out again.

I hear you on not wanting to see any justification for Soubi’s training. I am hoping that it will be one of those things that is good at low-to-mid levels of fighting, but turns out to be a big weakness at the highest level. After all, high level fights are conducted with words that are designed to wound emotionally, so if you have emotional weaknesses, that seems like it would be a big, well, weakness. ALTHOUGH, Soubi is the offense, and Ritsuka is the defense, so perhaps Ritsuka’s emotional toughness is what matters here.

Perhaps he will pull through with Ritsuka’s support, although that then raises questions of whether it’s right for Soubi, who was raised with conditional love, to benefit from Ritsuka’s can’t-help-but-be-unconditional love.

Usually I just conclude that Ritsuka and Soubi are about on the same level emotionally, and that they are a good fit for each other. Which says some pretty bad things about Soubi, considering that Ritsuka is in sixth grade :p

(And then you get into the whole sadism/masochism thing…)

You could also spin this as a Darren Aronofsky-like story about how high-performing individuals can have personal problems related to their professional excellence.

Pingback: Style and substance « MangaBlog

Ha ha, it’s a pretty late comment but your post just reminded me just how MUCH I love Loveless and Kouga Yun’s storytelling. Besides, I have never bothered analyzing inking style so it’s certainly something that I will pay more attention during a next rereading session! (On a side note, the first scene you analyze feature a cigarette and we learn later than Soubi only lits those in moments of extreme distress or suffering, physical suffering as in the aftermath of the nailed hand scene or emotional distress as during his first meeting with Ritsu in Goura after all those years).

About Soubi training “being right”, I should quote none but the author herself from an interview in a Japanese magazine done back in May 2005:

“Q: And that applies especially to Soubi.

K: Yes. The reason why people can’t understand Soubi easily is–despite the fact that he shows up so much he even has monologues–because they can’t see who he really loves, who he’s listening to, and who he’s rejecting. You probably can’t glimpse his true feelings until about volume 5.

A: Is that because Soubi himself doesn’t know either?

K: Yes yes, that’s it. I plan on making the moment when the fog-like something blanketing Soubi’s mind is completely lifted and he realizes what it is he seeks and what he wants to do the climax of the story. He’s given up. He’s despaired and abandoned [everything]. He doesn’t care about himself or about others, though he is swayed by liking Ritsuka a bit or feeling like he should listen to Seimei. The feeling that “It does matter!” will well up from within him, and that will be the climax.

Q: Is that the focal point of the theme?

K: Yes, that’s right. Most people live their everyday lives with an attitude of “Oh well, it doesn’t matter.” But I want to do a story where it does matter, with the idea of “being reborn” in mind…People are born as babies. But their birth isn’t from their own volition. Their lives start regardless of them. Ritsuka and Soubi have both failed somewhere. It wasn’t supposed to be this way…They weren’t able to proceed towards the ideal that they want to be, and ended up going in a different direction. I think there are a lot of real people who wonder what they should do in that situation, because they don’t like how they are now very much. What can they do then? They can say “This time I’m going to remake myself.” That can be triggered when they feel that “It does matter!” That life isn’t trivial, that they want to start over, that they want to change…But Ritsuka and Soubi are both lacking the internal strength to do that. And so they have to change little by little as they interact with others and as the situation changes. When someone is trapped in a shell, unable to escape even though they want to, one can be deeply moved when a crack is formed for some reason and that person can emerge [from that shell]. That’s why this is not a story of someone who dies while still an egg. Even as they receive assistance, they break the shell from the inside and make themselves over once again. I want to make that the climax of the story.”

So definitely, Soubi will recreate himself and win by his own power rather some borrowed power (Seimei’s name) or a power squeezed out of him by fear and coercion (Ritsu’s “training”).

I’d like also to point out that much of what is unsightly dubbed “consensual BDSM” in the fandom is in fact sequels of child abuse, pictured with a perfect accuracy at that; it shouldn’t come as a surprise that people with troubled emotional pasts and low self-esteem/nonexistent boundaries can be easily manipulated by strong-willed people, place acceptance over bodily integrity and can’t recognize red flags.

Last but not least, Tokyopop’s translation was not that good of a job as it got over the top with sexual innuendos in some places where they were mere double entendre in Japanese or weren’t there at all, and botched Soubi’s lines in some scenes that were character establishing and made him more of a coherent and suffering character.