I would be hard pressed to pick a better mascot for the United States as an imperial hegemon than Mickey Mouse. In Egypt — as with most of the “developing world” — Mr. Mouse is ubiquitous: you can see his big round eyes staring at you on the side of taxi cabs, through the glass windows of clothing stores, and from the cover of popular comic books. In fact, it is in this latter form that many Egyptians have come to know and love Mickey Mouse, or rather have come to know and love “Mîkî.”

In 1959, Egyptian publisher Dar Al-Hilal began printing Mickey Mouse and friends comics geared towards children in the form of a weekly magazine simply called Miki. Through a licensing agreement with Disney, the comics were translated from English into Arabic for an eagerly receptive Arab audience (eager enough to warrant 70,000 to 80,000 weekly copies at the height of Miki’s popularity) with all the original artwork in tact. This arangment continued until 2003 when Disney fees became “exorbitant” according to Dar-Al-HIlal and the publishing house Nahdat Misr took over the duty of giving Mickey to the masses.* What I will examine today is how Dar Al-HIlal altered the comics in translation to effectively localize Mickey Mouse for an Egyptian audience and how this localization made Mickey Mouse a beloved vessel of Western imperialism.

In their seminal historical overview of Middle Eastern comics Arab Comic Strips: Politics of an Emerging Mass Culture, Allen Douglas and Fedwa Malti-Douglas fittingly call Mickey’s transition into Arabic “The Egyptianization of Mickey Mouse.” As they observe, Mickey Mouse’s localization included embedding two pages of indigenous comics before the translated ones, adding non-comic pages with games such as crossword puzzles, renaming the Disney characters with Arab names, and creating new regionally specific covers.** Therefore as Minnie Mouse became Mimi and Uncle Scrooge became Amm Dahab (which literally translates into “Uncle Gold”), Miki marketed itself as a unique Arab product rather than a re-presentation of an already established American product. Perhaps the best way to illustrate just how Egyptian Mickey became in this process is by looking at a sample of covers from Miki magazines I have accumulated from Cairo’s book markets.

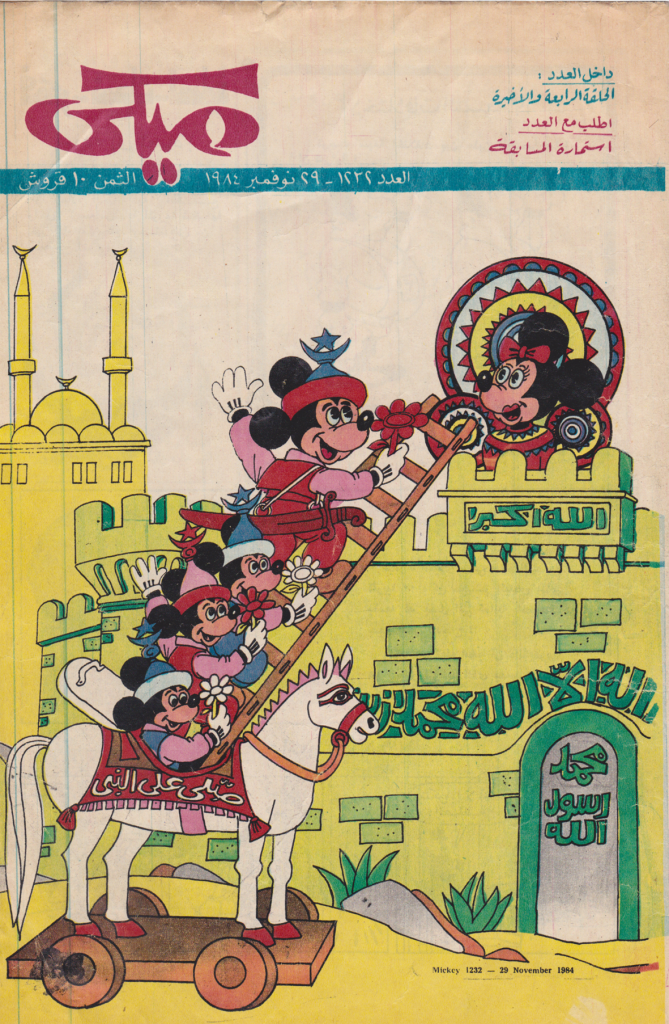

In this first cover Mickey, Minnie, and their illegitimate mice kin are seen celebrating Mawlid, better known to those outside of Egypt as the Prophet Muhammad’s birthday or Islamic Christmas. The illustration depicts Mickey climbing up a ladder to Minnie in front of a mosque and is embedded with a plethora of Mawlid symbology. The circles around Minnie are a reference to the edible treat Arusta-el Mawlid and the other mice are dressed in typical Mawlid dress (including the hat). On the building there is well-known Islamic script that reads “there is no god but Allah, and Muhammad is his messenger,” while on the horse (another Mawlid staple) it states “Bless the Prophet.” In short, Mickey is very much in the spirit of celebrating the Prophet Muhammad’s birthday.

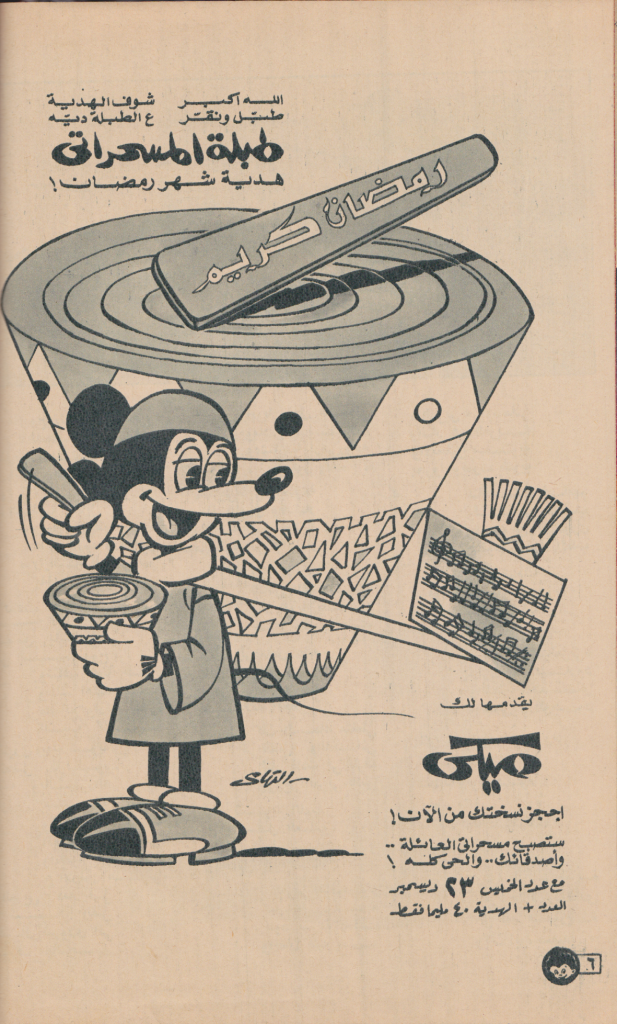

In this second cover, a gravity-defying Mickey is seen making the Ramadan treat kunefe (that is the special dough in his hand) in front of a storefront for “Mickey’s Kunefe.” Furthermore, he is wearing a traditional Egyptian galabia and cap associated with piousness. We can see another example of Mickey ready for Ramadan in this vintage ad for Miki magazine that ran in a 1956 issue of the popular children’s magazine Samir:

Here Mickey is studying the sheet music for his drum, which during Ramadan is played in the streets pre-sunrise to wake people so that they can eat and drink before the day of fasting. Up top the advertisement wishes you “Happy Ramadan.” I could literally continue with examples like this for quite some time (there is, after all, over forty years of Mickey being localized), but I will offer just one more quintessential instance of Mickey’s Egyptification:

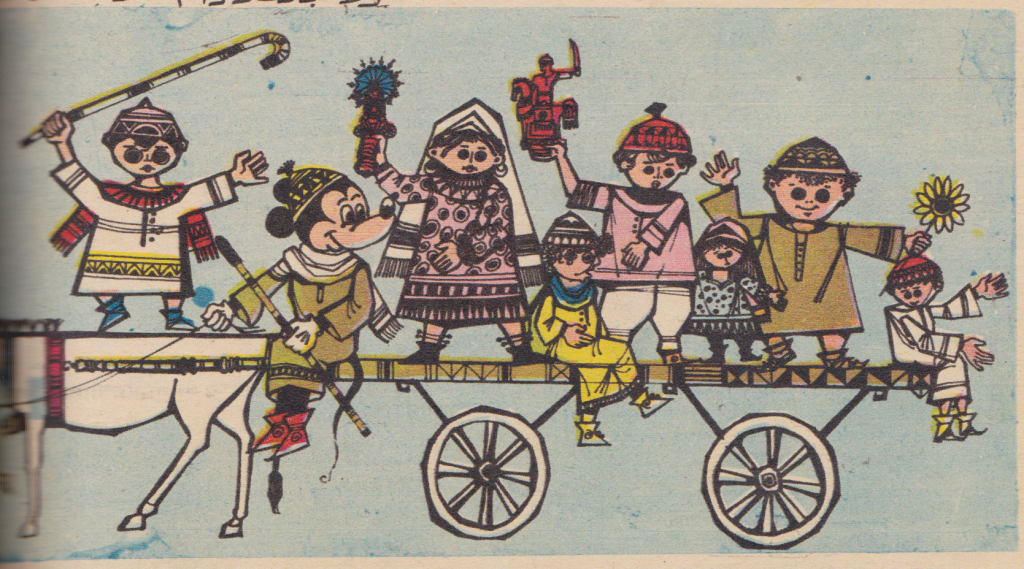

This scene from a 1950’s Miki illustrates the Mouse steering a bunch of children through the streets on a horse drawn cart. If you’ve ever walked the streets of Egypt during Eid than you will instantly get how well this illustration references the culture of which it is trying to assimilate. The takeaway throughout these illustrations is that Mickey is Egyptian: he will make your kunefe, bang your wake up drum, and take your children and his horse around the streets on Eid. Through this localization process, Mickey’s point of origin is obscured even though the majority of the magazine’s content remains distinctly American. Indeed, most Egyptian children may not know what Disneyland is, yet their sense of ownership to Mickey is as strong as any regular park-goers.

As was the case of Superman’s translation into Arabic, the perceived ownership of Mickey Mouse by an Arab audience exemplifies the pervasive reality of American imperialism. I have little doubt that this particular point is made more thoroughly by the remarkably-relevant and sadly out-of-print How to Read Donald Duck: Imperialist Ideology in the Disney Comic (1971), written in Spanish by Ariel Dorfman and Armand Mattelart about how Disney comics spread capitalist ideals throughout Latin America and the rest of the developing world. In their Marxist critique of Mickey and friends, Dorfman and Mattelart specifically observe how the relationship between Uncle Scrooge, Donald Duck, and his nephews is more commercially centered than familial (potently pointing out the conspicuous absence of mothers and fathers among the Disney characters). As Harold Hinds summarizes in his 1978 review of the book:

“[Uncle Scrooge and company] frequently set off on adventurous vacations, trips back to nature where they discover child-like noble savages. These simplistic, caricatured natives of the Third World benevolently enrich the adventurers. The undeveloped peoples innocently do not realize that the treasure or raw materials are valuable and are genuine products of their own labor or of a past culture from which they are descended. These fleeced natives also lack the wisdom of Donald’s nephews, who frequently must assert adult values, since Donald fails to. Incidentally, the nephews thereby internalize adult values, and thus ensure their own ‘colonization,’ while simultaneously colonizing the Third World adults.”

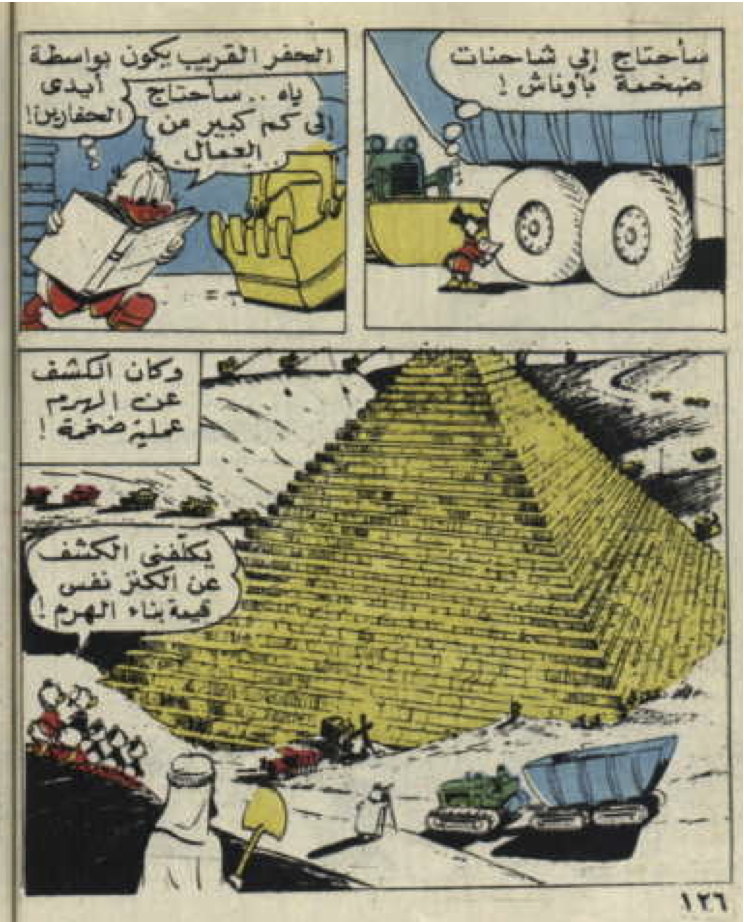

Indeed, this framework is visible throughout many of the adventures in the Arab-translated Miki magazines, including the time when Amm Dahab and the boys decide to vacation in Egypt. In need of rest after waddling through the Giza desert, Uncle Scrooge yelps when he mistakingly sits on a pointy object. Upon further inspection, he realizes that the object is the tip of an undiscovered pyramid buried in the sand.***

Although he initially argues they should abandon their find, Uncle Scrooge soon realizes that the king’s treasure might be sealed away in the pyramid. A few panels later, Amm Dahab (again, Uncle Gold) has hired a full crew of Disney Arabs to dig out his pyramid so he can claim the treasure.

After the pyramid is excavated, Amm Dahab uses a hieroglyphics translation book to find the room where the treasure is kept. Of course, to give the story the sort of comedic finale that the Disney audience had come to expect, there is no treasure, just a note from the King explaining he used all his fortune to build the pyramid. Like all good stories, it ends with Uncle Scrooge chasing Donald with his walking cane.

With Dorfman and Mattelart’s text in mind, this Duck tail reads as a remarkably imperialist narrative. The Western ducks discover a historical landmark that the Disney Arabs were incapable of finding on their own and what naturally follows their act of discovery in a foreign land is their immediate sense of ownership (Christopher Columbus much?). Furthermore, we as readers are lead to believe that the pyramids do not possess inherent value for their historical and cultural significance, but only for their ability to hold potential treasure. You see, without this treasure it wouldn’t have been worth digging out the pyramid, not worth hiring the cheap Arab labor. Lastly, we see the popular trope of Pharaonic culture being used as shorthand for all of Egyptian culture. In other words, traveling to Egypt for the Ducks is traveling into the past, not into a different contemporary culture.

Ultimately, I believe the real harm of this story is that it was tucked within the pages of a comic’s magazine that had Mickey wishing young readers Happy Ramadan or celebrating Mawlad on the cover. Mickey was localized insomuch as he could help Disney sell more comics globally, extending their commercial reach deep in to an emerging comic’s market. To be an avid Miki fans means to be an avid internalizer of the importance of capitalism and hence a way of seeing the world that makes certain countries first and others third. Mickey Mouse certainly has a big place in the history of Arab comics, but I believe it is a history whose depth we must challenge and whose psychological harm may be immeasurable.

—

*A full account of the publishing history can be found in the 2004 Al-Ahram Weekly article “My Favorite Mouse.”

** In the chapter “Mickey in Cairo, Ramsîs in Paris,” Douglas and Malti-Douglas go on to examine the salience of four indigenous strips that ran before the translated Disney pages of Miki in 1972. I would love to explore these strips in greater detail — especially the bizarre “Ramsîs in Paris” which recasts the Pharaonic figure in contemporary times as a living statue who escapes a life of boredom in Egypt for the perceived excitement of Paris, only to find Paris (i.e. the West) isn’t all that great — but that would be too extraneous for the purposes of this post. I instead encourage you to check out Arab Comic Strips or, at very least, look how weird Ramsis looks:

*** The following scans come via this useful site.

Huh. I’m not sure, Nadim, I totally agree with your interpretation– isn’t ‘arabising’ Miki the exact opposite of cultural imperialism?

I think the idea is that it’s a wolf in sheep’s clothing. The covers are Islamic, but the stories are American.

Which would mean that the comics were all made up of American reprints except for covers and pinups. I don’t think Nadim says one way or the other, though. If there were original Egyptian stories, I’d certainly be curious to hear about them.

It’s sort of a tricky question…on the one hand, you could argue that the need to translate a cultural product for another market demonstrates the limitations of imperialism. All cultures don’t become the same; rather, the “invading” culture has to be transformed before it can be accepted, becoming essentially a local product (Carl Wilson makes this argument about Celine Dion’s international success in his book about “Let’s Talk About Love.”)

On the other hand, Nadim is arguing that the alteration of Mickey Mouse is a kind of Trojan horse, making Disney’s racism and capitalism acceptable for an audience that might otherwise reject them.

I’m sort of torn, I guess. I find some of those covers really beautiful and weird — the Mawlid cover and the mickey as fish cover at the link in particular are pretty fabulous. But I can see how it would be really depressing for an Egyptian parent to see his or her kids reading stories that present Egypt in such a casually racist way.

Last paragraph or so, he mentions that there were some original Egyptian stories….

I am not sure about harm or non-harm either.

Here’s the way I see it, you have one culture injecting ideas foreign to a receiving culture. Is that necessarily a bad thing or not depends on what the interjecting culture is trying to achieve and also what is the effect on the receiving culture.

For example, my wife upon coming here (US) thought the whole pink is strictly for girls and blue is strictly for boys thing was weird. But I used to always get weirded out if I saw a toddler boy in pink while visiting India. So what has been interjected by the other culture? Gendered coloring. Again maybe bad or maybe good.

An example from my business classes:

In China, when McD’s went over there they had a policy to always smile and greet your customers. But in China smiling openly at someone is like laughing at them. So instead of changing its policy McDs put up a sign saying, when we smile its not because we are laughing at you but because its our policy and its means that we are happy to see you.

So again, what is the point of the cultural interjection. If it is saying that here is the standard of X (X being gender, pleasure, manners) and the Western/American standard IS the standard to go by (or buy) then there is a harm… its basically saying that the receiving culture’s standards are substandard.

I don’t know if that made sense.

– Seafire

McD’s response is weird. The employees are local, so it would be simpler to let them do what comes naturally and not smile at strangers.

NOAH, where that book says “the ‘invading’ culture has to be transformed before it can be accepted, becoming essentially a local product”

I’d say “transformed” and “essentially” don’t match the Egyptian Mickey examples here. Watching him do Islamic things isn’t that different from watching him play Santa Claus. The arrangement is like Disney’s standard “customs of many lands” approach but with greater authenticity of detail.

I would say the corp. response is not weird if its trying to make its own transition easier into a emerging market. If the country is too foreign or exotic change the culture’s ways to make it more understandable to you the western corp. But of course leave room for the local countries tastes so that the new goods aren’t completely foreign to the foreign country.

Yeah; Carl Wilson was talking in a little more detail about how Celine Dion’s music is used in different cultures, how she has to sing in different languages, etc.

It’s a little hard to tell exactly what’s happening with the Egyptian Micky. But…the art style, for example, seems fairly different from what it would be in the U.S. And Nadim notes that it includes some original comics as well…. It seems like you could argue either way….

One of the things about cultures is that they’re not unitary or fixed. They’re permeable to begin with. There’s a real sense in which Egypt and the U.S. are part of the same culture, for example, even though there’s also a (perhaps more) persuasive case to be made that they’re not. And as an example of how complicated things can get — McDonald’s response could pretty easily be done precisely to emphasize it’s difference/Americanness. Lots of cultures have a cultural interest in appreciating/appropriating other cultures.

Interesting article!

Just wanted to note that the pyramid story is by Carl Barks, from Uncle Scrooge #25 (1959).

I knew it! Beautiful pyramid.

“Lots of cultures have a cultural interest in appreciating/appropriating other cultures.”

Exactly and its this kind of stuff that gets me into fits of laughter!

Is Mickey part of a larger plot of Western cultural imperialism or is he just a symbol of modernization?

Seller: Hey I’m selling this Egyptian made shirt its worth 5 Egyptian pounds

Buyer: Yeah why would I buy that crap

Seller 2: Hey I’m selling this shirt its got a crocodile symbol with the words (mis)spelled LaaCoste on it, made in Amrika

Buyer: yeah give me 10 of those

Westernization = modernization or does it just equal erosion of home values and tastes? Do we hate the west or do we love the west?

I go to India 10 years ago its the same polluted, same shoving and pushing crap going on

I go to India last year and I am going to a grocery store(!) not a street vendor for my fruits and vegetables; I’m standing in line with my brother in law and we look over to something on the side ziiipp there goes the line cutters as usual but wait… to my surprise the cash register lady takes that guy’s goods puts them to the side and takes my goods first

hmmm maybe its just progress.. maybe its not cultural imperialism?

I am of the wait and see approach to see if this is progress or cultural imperialism. I think its still too soon to say what is going on.

“McD’s response is weird. The employees are local, so it would be simpler to let them do what comes naturally and not smile at strangers.”

I’m not even sure if that McDonald’s anecdote is accurate in the first place. If they were smiling like air stewardesses, definitely (I can’t believe that the appreciation of blatant insincerity is uniquely American). On the other hand, you’ll find service staff smiling pleasantly at you often enough when you’re in China. The Chinese are definitely more surly than the Indians though.

Anyway, for the kind of wages McDonald’s pays, you can be sure that not many employees make it a point to smile in the first place (whatever the reasons).

Noah: Re – Celine Dion’s “problems”. Hong Kong singers (who usually record in Cantonese) often record in Mandarin in order to break into the China/Taiwanese market. So the language thing has more to do with commerce/greed than “culture” surely.

I like your point that “lots of cultures have a cultural interest in appreciating/appropriating other cultures.” I don’t know about the appreciating part but I would say that the Chinese have shown a reasonably large tendency to appropriate things over the years (esp. considering they were the dominant culture in the region for hundreds of years).

Well, it has to do with commerce and culture. The two aren’t all that separable. Wilson was responding to the idea that globalization flattens difference — that flattening including an adoption of English. And he was arguing that, no, actually, globalization means not that everyone listens to Celine Dion, but rather than everyone listens to their own Celine Dion. And they listen not by abandoning their language, but by forcing her to abandon hers (though she is originally a French speaker, I think, which Wilson talks about too.)

Appreciating seems like a part of appropriating, though not the only part. The reason it all seems (possibly) ominous or unpleasant is that it often seems so one-way — that is, Egyptians appropriate Mickey Mouse, but what do we get from Egyptian culture (other than possibly some cuisine?) There’s more balance with Japan or even India or China, but when the culture flow is so one way, it does start to seem like imperialism (especially when there is a real history of actual, not just cultural, imperialism to back it up.)

And thanks for calling bullshit on the China McD story. It’s amazing how gullible I can be about stuff like that, even when it’s clear I should know better….

The biz class I took was about 10-15 years ago, so I don’t know how old the anecdote about McDs is itself. But the way it was described in the textbook was that in China smiling at a stranger you don’t know was considered rude. I’ll admit that I don’t know anything about Chinese culture but it sounds like a believable story to me.

American corporations not completely accommodating to the culture that they go into is not such a far fetched idea.

I don’t see how its bullshit just because it sounds strange.

I think the point that’s being made — that American businesses might not just accommodate — makes a lot of sense.

I’m just inclined to believe Suat when he says it’s not right — not because it sounds strange, but because he lives in that part of the world (Singapore) and has (I believe) spent time in mainland China.

If you took the class 15 years ago, the anecdote could be another 10 or 15 years old, which starts putting it back a bit, and things could definitely have changed in that amount of time (especially in China.) On the other hand…textbooks should in general not be trusted. I say this as somebody who used to write them.

Noah: You still write textbook like books, don’t you?

Actually, Seafire could well be right. I meet mainland Chinese virtually every day at work BUT have only been in China for a grand total of < 2 months. So I'm not an authority on the matter.

On the other hand, there's nothing to prevent corporate actions from being totally illogical. All you need is one poll or advisor to get these things running. Everyone has heard the famous story about Oreo cookies with more fillings for the Chinese market as well, right? I bought a pack while in China and they do seem to better filled (not ostentatiously so) than your average Oreos. The question is whether Americans don't like more cream filling in their Oreos, or is it just something Nabisco can get away with in the U.S. So Oreos aren't actually a big cultural weapon but hopefully you get my drift. Survey don't always tell the whole story.

"There’s more balance with Japan or even India or China, but when the culture flow is so one way, it does start to seem like imperialism (especially when there is a real history of actual, not just cultural, imperialism to back it up.)"

Well, a really complex issue which won't be settled in these comments. The balance is important and so is the "strength" of the local culture (which I suppose depends on historical factors and population size).

In general, I think it may be useful to see "appropriations" as a positive thing. No one complains about a trade imbalance in their favor. One might say the same for culture in our present age where wars of conquest are much diminished. I think the constant absorption of foreign "product" can only strengthen an already resilient culture. In general, a one way cultural flow only harms the "exporter" in the long run.

In any case, there are also lessons from history. China has been conquered twice in its history (and for centuries). In the case of the Manchus, it has completely assimilated that culture (the Manchu officials were sinicized over the centuries and the language appears to be kept alive by "Chinese" scholars today). The Manchus for their part probably rid the populace of a weak and ineffectual dynasty. Also, I vaguely remember reading somewhere that we wouldn't have The Secret History of the Mongols without transcriptions from Chinese sources.

I think it is a bit troubling that so many "famous" Indian novelists write primarily in English today (naturally a by-product of colonization). At least, the ones which reach an international audience do. Seafire, do you think Indian culture is resilient enough to overcome "imperialistic" challenges? On balance and on purely anecdotal evidence, I would think so – India still seems very very Indian to me.

In the same way, I see very little chance of Egyptian-Islamic culture being overwhelmed by Western culture imperialism presently, but someone like Nadim (who's on the ground) would know better. It's not a "weak" culture and I wouldn't spend too many brain cells worrying about them.

Pingback: Mickey Mouse in Egypt | ofellabuta

India is a huge exporter of culture regionally I think — Bollywood cinema is kind of a massive deal.

Cultural exports have less to do with country size than with economic size, I think….

It’s all a bit ironic, though– many Arabs resent Egypt’s cultural dominance. Egyptian films, songs, tv shows, and books blanket the Arab world. Even Egyptian Arabic influences other dialects significantly, I’m told.

BTW, if Nadim hasn’t replied yet– I believe it’s because he’s currently in Egypt.

AHEM!

Get out safe if so, Nadim.

Hey everyone! I just got out of Cairo and have Internet for the first time in over a week. I just wanted to say thanks for the spirited discussion (which I will hopefully catch up on soon) and make a note that the post needed some more edits before going up. Anyways, I have a crazy amount of e-mails to respond to and people to let know I’m alive, so I hope to get back to this space soon.

That’s a huge relief. We’ll look forward to hearing from you when things calm down a little. Thanks for taking the time to reassure us!

Whew!

Pingback: Mickey Mouse in Egypt | Robot 6 @ Comic Book Resources – Covering Comic Book News and Entertainment

Pingback: Tweets that mention Made For You and Me: Localizing Disney’s Imperialism for an Egyptian Audience « The Hooded Utilitarian -- Topsy.com

Pingback: Made For You and Me: Localizing Disney's Imperialism for an … | Cartoon World

Pingback: Wonderful things I read in 2011, or thankf******god for bookmarks « The Blog of Disquiet

I am is-hak Barsoumian =born in 1947 Beirut/LEBANON , (living in London since 1979) to ARMENIAN parents, when 1 was 6-7 years old i used to accompany my elders to the Cinema theatres ,to see Arabic /Egyptian movies..as Egypt was the Hollywood of the Middle East..those good old days?? Each theatre used to show ..for a starter 1 or 2 comic cartoon films ,some showed bugs bunny/TOM &JERRY/Popeye the Sailor man /Porky Pig and few others showed : Mickey Mouse/Donald Duck/Goofy/Pluto all depended on theatres contracts with this or that Hollywood Giant Film Companies such as Warner brothers /Metro Goldwyn Mayer etc….etc.. We as kids ,LOVED Mickey a lot , as He was Cool/Cute/Courageous…even though DELL American Comics were on sale in Beirut& even French translated books too, but no Arabic Mickey was available ?? let alone in Armenian , my Mother language? We didn t have to wait ..long as on 17th April 1958 thankfully Egypt s Giant publishing house DAR EL HILAL ..made our dreams ..come true? as a pilot edition of Arabic Mickey was on sale under the title / SAMIR introduces MICKEY /..to its young readers , SAMIR or SAMEER however it s spelled, was published by the same P.House as first kids mag. published on April 1956..and was very popular among the young readers ..then!! MICKEY began monthly then periodically . but always on Thursdays,it became weekly by New Year January1962?! But this didn t mean, we the kids ,abandoned SAMIR for MICKEY, NO!! because Samir s cartoon/heroes were local characters from our daily Eastern environment, As Mickey s Characters were mostly Cats/Dogs/ Pigs (as much as Pigs are cursed animals in the Arab world??) and the story plots were too advanced to sink in a kid growing up in the east? and sometimes considered .. Violent and Harsh and when Arab Kids copied some of it as a joke ,they got hurt or detained by the grown ups! at home or school. but as one wise man claimed : CHANGE MUST COME .. maybe for us long awaiting kids for Arabic MICKEY..this sudden /shocking Change came..TOO EARLY??? best wishes to all from London/G.Britain Is-hak barsoumian