The traffic moved swiftly on the West Side Highway past the busy shipping lanes of the Hudson River on a bright day in November 2009. The memory of commerce and trade once dependent on the port traffic, hangs on in the refurbished warehouses and lofts, which now house the Chelsea Galleries and remind one of New York’s vital history. The Bill Viola exhibition “Bodies of Light” on display at the James Cohan Gallery in the heart of the Chelsea gallery district included a collection of works from different periods during the previous eight years. I went to the exhibition on a recommendation from a professor friend, charged to evaluate the exhibition in the light of the critical acclaim that Viola enjoys. Much of what is written about his work is positive and Viola is often interviewed with the caveat that his work is assumed to be worthy of his postscriptive comments. The wide range of works presented offered an opportunity to view his recent corpus and perhaps gather insights about the reasons for Viola’s favorable notices from the art world, the public and even religious intuitions. I entered the gallery unfamiliar with his work, but not unfamiliar with the realm of the Chelsea galleries, or so I thought. I offer here my thoughts and experiences as I recorded them subsequent to that first visit when I stepped into the gallery from the cold brightness of a winter day.

The installations are exhibited in darkened rooms where the only light to illuminate the space comes from the medium of the objects, that of various types of projection from video films and architectural video installations to flat screen pieces. The installation has a sound element that is either ambient or residual as it frees itself from the mooring of the artwork to which it belongs. The illuminations connect as points of visual stimulus throughout the rooms to draw the viewer from one piece to the next. As one becomes accustomed to the disorientation of the dark and the rushing indeterminate sounds, the works seem to deal with emotions and the human condition, but then move on to otherworldly matters as the figures emit and are bathed with brilliant and searing lights.

Many of the works come from the series “Transfigurations”; they are flatscreen projections that appear like moving pictures since they are hung as traditional paintings, flush to the wall. The three dimensional images produce an unsettling depth of field. White noise accompanies the images, which begin in the black and white static of a 1970’s surveillance camera, from which the human actors in the images emerge. As they come forward, they apparently cross through a wall of water where they assume human colors. Once in the foreground, they display both emotions and lack of emotion, but typically gaze out of the two dimensional screen with a three dimensional presence. The titles of the works bear titles such as Acceptance (2008), Incarnation (2008), The Innocents (2008) and Small Saints (2008). Viola writes:

The transformation of the Self, usually provoked by a profound inner revelation or an overwhelming sensation of clarity and fathomless emotion, overcomes the individual until literally a ‘new light’ dawns on him or her… Some of the most profound human experiences occur at times like these, arising at the outer limits of conscious awareness (cited in gallery press release).

Viola also acknowledges the religious reference in his works and has made works explicitly to be shown in Christian settings[i], although his works are not limited by a Judaeo/Christian approach. Rather as made clear in the press release, they “have roots in Eastern and Western art as well as spiritual traditions.” So for the moment, let it be conceded that Viola embraces a kind of theism and accept this fact as perhaps rupturing the notion of the function of a “modern art” gallery.[ii] The spiritual possibilities in certain of the series require recognition.

In the piece farthest away from the entrance, Incarnation[iii], a naked couple emerges from the white noise and a coalescence of static moving specks on the (approximately) five foot high screen. Viola juxtaposes a variety of signs and signifiers, and structuralist tropes of media, such as the self-referential white noise, aural and visual sonic blizzards and distressed image surfaces, in the invocation of narrative[iv] passages. Structuralist cinematic tropes typically used to fracture the illusion of truth are conversely used to create the illusion of truth. The distress and use of the media which one might expect to see in a structuralist film, to be self-referential to the medium of film (video), here is used to suggest that everything is not real. They are used to delineate a para-unreality or meta-reality. Further, Viola uses actors in the works, who assume the role of artist’s model beyond the presentation of timeless everyman, and Viola anticipates an audience in the production of the work. The technical aspects that allow for the dazzling light displays as the figures cross the sheet of water is masterfully controlled and lit. The water is invisible until the human form intersects with it and then the water becomes visible against the dark backgrounds, covering the body in veils and sheaths of white. His work is not accidental; it is a considered construction. It is deliberate and skillful in its choices.

As I watch the exaggerated facial expressions of the Asian man as he emerges in Incarnation, I think of Roland Barthes’ early essay “All in Wrestling” from Mythologies that points to western readiness to engage in any spectacle, particularly those that portray stereotypes and grossly exaggerated gestures and affects with predictable outcomes. In wrestling, the anticipation is rewarded by a variety of signifiers and symbolic gestures that allow for a distancing in the spectacle of others’ battle with good and evil. Barthes writes, “The public is completely uninterested in knowing whether the contest is rigged or not, and rightly so; it abandons itself to the primary virtue of the spectacle,” the wrestlers/actors know how to “play up to the capacity of indignation” (15. 21. Barthes). Kathleen Marie Higgins quotes Danto who picks up the notion of moral indignation by, “ours is an age of moral indignation,” as she elucidates the point that “to find beauty in images of suffering, to seek aesthetic satisfaction where moral injustice prevails is, in his view a moral failing” (qtd. in Beech 31). Viola side-steps this issue by deftly inserting the cohort of beauty, the sublime, into the negative space and by claiming the redemptive power of the transformative experience. He sutures the spiritual experience to the sublime experience. Even as the show’s title, “Bodies of Light,” encompasses the human form, it also implies both the option of a photo-centric and a supernatural reading. However, Viola is no less adept with his semiological manipulations than any other producer of spectacle, whether a wrestling match or a Broadway extravaganza designed to produce a good show. And rather than deconstruct, he constructs a mythology in which he assumes a quasi-religious stature of artist as divine intermediary.

Yet, if we are such willing participants in spectacles, where the viewer might agree to engage in the mysticism and otherworldly qualities of a revelatory, transformative, interactive medium, perhaps the sophisticated series might point slyly to our post-medieval longing to experience the sublime of the gothic cathedral, and to reclaim the uncanny of gothic sublimity in the terms of the post-post modern technology. Viola created various works, the first of which was Ocean Without a Shore, for a religious setting in Venice at the San Gallo chapel, and in this show perhaps references the spiritual light displays of Bernini’s artfully constructed Ecstasy of St. Teresa for Venetian Cardinal Federico Cornaro (1579–1673). As a part of the counter-reformation’s effort to reclaim the lost Protestants, Bernini was employed to create a display that would be so dazzling as to bring them back to the fold. He created the sculpture of St. Teresa with her ecstatic expression of suffering and the shards of golden light shooting out of her body as she floats transcendentally above the earthly plane. The point here is that the same skillful deployment of light techniques and affect that were employed in the Renaissance are employed by Viola.

Of course, the Bernini sculpture is staggering in its sublimity, but at the same time it is a sales ploy for the Catholic Church, who felt its power on the wane. However, the function of the art was made explicit by its location in a church, not so obvious in the setting of the New York gallery. The competence of the series’ production values troubles me inasmuch as nothing is left to chance. I feel as though I am being shepherded into a religious experience. What happens if I do not want to buy? Still, the images are compelling.

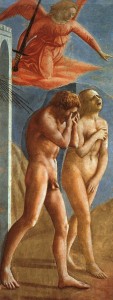

Almost immediately, in Viola’s production, the body gestures of the couple bring to mind the Masaccio painting of Adam and Eve’s expulsion from the Garden of Eden. The gothic reference makes its presence felt by replicating the medieval cathedral’s environment, with the darkened rooms and the stained glass windows of the images theatrically lighting the mysterious spaces. More gothic than humanist, the expressions on the faces of the couple that emerge from the water are not ecstatic. Once in full color and spectacularly naked, the Asian man and Caucasian woman gaze out at the viewer with shame and horror to bring the work past the primary transformation narrative and into a more complicated sphere of affect.[v] They don’t seem ecstatic as they emerge from the other interior space and one wonders if their experience in this alternate imaginary is more akin to purgatory. It is surprising to me that post-modern people would so readily embrace the mythologies of a pre-humanist culture as his almost-universally positive reception from the press would imply. In a church one anticipates a religious manifestation, but in a gallery there is a different social contract especially since a Chelsea gallery is not an historic repository.

Within the narrative of the picture box/flatscreen, the figures come and go at will. The viewer has no control of the figures. The actors do not present themselves for viewing; rather they come in on their own terms slowly, as if great effort is required to escape another realm’s pull. Also, by the slowing down of the actors’ movements who seem to move out of time, the heimlichkeit of the known presented by the naked human form is also made unheimlichkeit by the unfamiliarity of the timing. The uncanny is already at play, as the gallery has altered its function from a place where one can see works of art in bright light, to a disturbing one where the images appear from occluded and hidden spaces. The images are not what we expect to see in a gallery. There is uncertainty about the social nature of the space. I use the German term for the uncanny, because I want to think about “unhomeliness.” Television and video (momentarily I grant) are as yet still personal, still in our homes and in our domestic lives. We usually go out to the cinema to experience film, unless it is in DVD, video or on the TV. Some of the most successful horror films draw on the idea of video and television as portals through which wicked creatures enter our homes, for example “The Ring” and the “Poltergeist” series. Viola creates the illusion that we are looking at familiar forms, i.e. humans, but coming from unfamiliar realms, i.e. the immaterial realm of the undefined. It is not the first time I have seen special effects manipulate my emotions. Yet certainly, the images Viola presents are arresting. They are mesmerizing.

Disturbingly, the couple invokes the repetition of trauma as they loop in their action over and over. From our position as viewer, we try to understand the affects of the persons who gaze on us from the frame of the image space. Time seems to have slowed down in their world and this allows us to examine their expressions in a way that is typically denied in everyday life. The Asian man seems horrified to see the viewer. His appalled gaze is particularly disturbing, because it comes without vocalization and one imagines that there is something of the “Real” as in Lacanian terms, it again renders the couple primal. The Asian man, who seems to be in distress, returns over and over if one waits. The viewer may change, what the viewer sees will change with the perception of the viewer, but the repetition continues. As Lacan says, the real always returns and while “it,” the object of repetition may be slightly different, the pattern is the same. In some way, we are witnessing a traumatic representation, but the apparently transfiguring event of the purging of identity, as the water covers the individuals in sheaths of water, recalls both the caul of birth and the shroud of death. Even if one sets aside the symbolism of water as a cleansing agent, the visual erasure of all expressions appears to wipe away their identity. One asks as he emerges troubled, not reborn or free of his past, why is his affect not empty? As they penetrate the wall of water his mean is startled and horrified by the world beyond and most disturbingly by the vision of me? Perhaps lured by the symbolism one asks, why did the rite of purification not leave him free from pain?

Instead, his face is a mirror to remind me of my own desire to exist. Perhaps this takes me back to the mirror stage when I am separated from my “real” self for the first time. I imagine he sees himself in me. I witness the first moment of separation from the “real” and I am separated from myself again, because I see his horror and recognize it. But, I am merely a voyeur and I do nothing. I split myself in two so that I can remain viewer and participant in a non-affective relationship and yet, the proximity the of the naked man’s anguished face still stirs a response as one anticipates the transformative interaction. One hopes to learn something from his experience of this meta-mystical space.

We experience the people in the representations as protagonists of ontogeny in our narcissistic fashion, but they are disturbing because they remind us of our own lack. They are divided from the Symbolic order by which the viewer operates, except that the intrusion of religion into the equation allows for a moment when the imaginary can suture stereotype figures, here as Adam and Eve, or even the unknowable feminine infinity, as embodied in the framed religious ecstasy/agony.[vi]

In a moebius strip of topology, the repression of the images returns time after time after … The anguish of the actors is eternal, but because this is a gallery, the sufferers are locked into the picture frame and the viewer is at liberty to leave. Unlike Barthes’ comments about the full light of the wrestling match, this assumption of privileged gaze and delectation of guilt is purely for consumption. It is far beyond the Kantian sublimity that lets us watch in safe horror from our seats. The sublime here follows more closely the Lacanian understanding of the sublime, but language do we use to reify the sublime wow? We are in the dark, literally and metaphorically, so that we can enjoy our responses and jouissance in an anonymous, unseen setting.

In The Imaginary Signifier, Christian Metz describes the relationship of the viewer to cinema as one in which the viewer is instrumental:

There are two cones in the auditorium: one ending on the screen and starting both in the projection box and in the spectator’s vision insofar as it is projective, and one starting from the screen and ‘deposited’ in the spectator’s perception insofar as it is introjective (on the retina, a second screen). When I say that ‘I see’ the film, I mean thereby a unique mixture of two contrary currents: the film is what I receive, and it is also what I release, since it does not pre-exist my entering the auditorium and I only need close my eyes to suppress it. Releasing it, I am the projector, receiving it, I am the screen; in both these figures together, I am the camera, which points and yet which records ( 51).

The video screen is not a film screen, but it is coterminous. However, the configuration of back-projected video no longer needs over-the-shoulder projection, or the transferred projection- from-self. Metz’s claim, which gives power to the viewer (in what might even be seen as a political gesture) is not sufficient in the gallery setting with the back-lit flatscreens. Video can be experienced from the side and the front; the viewer is not restricted to his or her seat. Metz’s claim for the viewer as source of projection and the reassurance provided by the presence of cinematic light, which conveys the Lacanian “symbolic” onto the screen is void. They are absent. Metz notes that “the cinema is already on the side of the symbolic (which is only to be expected)” because “without this presence there would be no intelligible unfolding of the film,” and I suggest this alignment of self-production makes the cinema a sanctioned and protected site from which to experience film (46). In contrast, the absence of the symbolic beaming eye contributes to make Viola’s work more unsettling. The viewer no longer occupies the instrumental role so familiar in the older technology of film, but instead the images technologically generate themselves. On the most fundamental level, light emits from the screen. And while I hesitate to return to the earlier reference of unheimlichness, which I noted in relation to the narrative content, one must again observe that the familiar is rendered unfamiliar in and by the technology. Video is neither fish nor fowl; not television or film. The technology disconcerts, at least for the moment, because the varied scale of the screens, their abundance and the setting all conspire to challenge the familiar interaction of video as domestic tool. Again my use of unheimlich is specific, because as I previously noted, the realm of video has been (until recent cinematic uses) in the home. It is the method we use to record our familial rituals; birthdays and weddings. Here it appears to record arcane human experiences of realms only imagined. Viola’s images portray the world of the dead and this is a taboo.

Viola capitalizes on the effect. He utilizes the two dimensional surface of the screen in a gallery setting to articulate the limits of the newer medium. The hidden projection presses film and television as it chaffs the apparently narrow technological differences, which are close in terms of the human experience, as can be understood if one remembers Metz’s conception of human interaction with the projected image. In speaking of film he says:

…Thus the constitution of the signifier in the cinema depends on a series of mirror-effects organized in a chain, and not on a single reduplication. In this the cinema as a topography resembles that other ‘space’, the technical equipment (camera, projector, filmstrip, screen, etc.), the objective precondition of the whole institution: as we know, the apparatuses too contain a series of mirrors, lenses, apertures and shutters, ground glasses, through which the cone of light passes: a further reduplication in which the equipment becomes a metaphor (as well as the real source) for the mental process instituted. Further on we shall see that it is also its fetish(51).

It should not surprise that cinema and its paraphernalia should become fetishized, any more than should the gratification derived from the immersive nature of the emergent technologies for themselves tout court. The viewer maps personally and metaphorically onto video technology. The engagement feels historical, which is to say that we are willing to watch a looped sequence in the same way that that our great-grandparents watched a zoetrope or nickelodeon. At times the content becomes secondary to the experience of the technology. The difference results in a complex distention and retraction of temporality.

The technology captures the sensation of spectacle and of a strange funhouse. In the gallery at Viola’s exhibition, the temporal is brought into a self-conscious immanence. In one work, an indistinct sound of a child’s voice is heard and one is reminded of childhood, but the resonance is experienced more properly in the novelty of the video event. It returns one to the place where all things are at the edge of anticipation. It exceeds the quotidian. It agitates the body. The images of humanity close to transcendence, which line the walls, are at the other end of temporal immanence and the distance that Viola creates in the proscenium stage of the image, if one may now see the images as theatrical events, forces the viewer into a consideration of representation and reception. Yet video, like film and theatre resists easy analysis.

Metz’ attempt is further to discern cinema’s signifier, as “perceptual the visual and the auditory” (42). He separates the visual and auditory to better understand their temporal and spatial relationships and attempts to categorize the various “axis of perception” with respect first to theatre and then to cinema (43). He enumerates the registers of perception and concludes that compared to theatre “…this as it were, numerical ‘superiority’ disappears if the cinema is compared to theatre” (43). The yield for him is to admit the presence of the real in theatre where everything, the actors, the props and the audience are actually present and to acknowledge the absence of the real in cinema. He concedes, “… the activity of perception which it involves is real (the cinema is not a phantasy), but the perceived is not really the object, it is a shade, its phantom, its double, its replica in a new kind of mirror” (45). In representations of mysticism, the medium maps perfectly onto esoteric representations, which is perhaps why the surrealists were so immediately drawn to film, because it allowed fantasy to take form through phantasy. For Viola, the same holds true. The illusion of the supernatural is perfectly represented in the unreality of video. Metz finally announces: “Every film is fiction film” (44). The unreality of the objects makes film unreal, and the same may be said of video. The actors are not present in physical form, nor are the props. Nothing but the play of light through a system of electronic pulses informs the viewer’s episteme, so that when in Incarnation the two figures emerge through the invisible sheet of water, they are as insubstantial as if they were nothing more than shades. The water which sprays from them in white shards and encases them almost as shrouds might, is nothing more or less than light and its absence. It is perhaps this mapping of what we desire to see, the image of the unreal, represented in the unreal that forms a double negative to make it credible to us. Metz elaborates the notion of the duality of absence and presence:

What is characteristic of the cinema is not the imaginary that it may happen to represent, but the imaginary that it is from the start, the imaginary that constitutes it as a signifier (the two are not unrelated; it is so well able to represent it because it is it; however it is it even when it no longer represents it). The (possible) reduplication inaugurating the intention of fiction is preceded in the cinema by a first reduplication, always-already achieved, which inaugurates the signifier. The imaginary, by definition, combines within it a certain presence and a certain absence. In the cinema it is not just the fictional signified, if there is one, that is thus made present in the mode of absence, it is from the outset the signifier(54).

The cinema and video overlap in this regard and Metz gives to this vein of commonality, more to complicate the reception of the image in the viewer. He writes in a passage relevant to both media:

The unique position of the cinema (video)[vii] lies in this dual character of its signifier: unaccustomed perceptual wealth, but at the same time stamped with unreality to an unusual degree, and from the very outset. More than any other arts, or in a more unique way, the cinema involves us in the imaginary: it drums up all perception, but to switch it over into its own absence, which is none the less the only signifier present (45).

In Viola’s work this abundant richness presents the viewer with immensely realistic–looking images. The human form in his work is seen with all its flaws, its humanity is available for close inspection, except that it is absent. This allows for the space in the imagination to take over and supply the additional narrative to make the move into the metaphysical realm. Yet all of this metaphysicality is only the product of high level photography and spectacle. Viola adds thrashing sound of torrents of water to the images and this adds to the sense of terror, awe and premonition so that in his video he creates a mise en scene that spills from the contained images on the walls into the larger free space of the gallery.

The people depicted in Incarnation do not speak. They do not cry out, they simply move their mouths in preparation to speak, but then turn away as if they know they will not be heard. The expression is caught in mid-gesture. One might at this point follow the thoughts of Mark Hansen who sees in the slow and the almost imperceptible gestures of affect seen elsewhere in Viola’s work a chance to experience the interstitial moments that one is typically denied in normal life. He is speaking of another work in a series that show human faces that change expression in slow motion[viii]. Hansen expresses his surprise:

It slowly dawns on you that what you are standing in front of are images portraying the vicissitudes of life that, paradoxically, remain imperceptible to your eye…So what you have in fact encountered in this work is the rich texture of the microstages in between recognizable or discreet emotional stages. Normally imperceptible because they happen too fast for the eye to register (at least with any capacity of cognitive reflection), here these interstitial microstages of affectivity are imperceptible because they happen too slowly; in these effectively static images, you simply cannot perceive the incremental series of changes filling the unmarked continuum between discreet emotional states as anything like a continuity (587).

Hansen, who writes at length about the temporality of this work, in fact notes in passing the particular quality of video that allows this type of minutiae of representation to become observable. He remarks in passing “the rich texture” that technically allows this to happen. It reiterates Metz’s thought about cinema’s “unaccustomed perceptual wealth,” which I would suggest is amplified in video. It is exponentially richer, because video is not made up of a number of frames to the minute but is almost seamless in its physical composition. The interstitial spaces are imperceptible to the eye, not contingent upon the imaginary work done by the brain to constitute the experience of film. It is this digitally generated imagery that allows for the sustained detail on screen, which introduces such evenly rich mimetic representations. So detailed is the information presented in the digital medium that it surpasses the ability of the human eye in its normal function, to provide hyper real images with a plethora of details and epistemological rewards. This is perhaps the source of pleasure. It remains tied to Aristotle’s analysis.[ix] For him the human being takes pleasure in learning by mimesis or representation and thus as a result all forms of the arts are pleasurable to us as they are mimetic, (but especially theatre which causes the most pleasure). In common parlance, this is eye-candy.

Hansen invokes, a plethora of renowned critics to respond to (what he names) the time-image and this is germane to the Incarnation piece, which slowly moves to show the strong affect in the two figures:

Contrasted with Deleuze’s conception, Gordon’s work thus relocates the time-image from a purely mental space contained, as it were, within or between the formal linkages of a film to an embodied negotiation with the interstice or between-two of images that necessarily takes place through the affective experience of each specific viewer-participant. For this reason, Gordon’s work exposes the fundamental limitation of Deleuze’s conception of the cinema of the brain: the isomorphism between the cinema of the time-image and the contemporary brain. To understand how cinema has changed, Deleuze has argued, one must look to the modern revolution in brain science: “Intellectual cinema has changed, not because it has become more concrete (it was so from the outset), but because there has been a simultaneous change in our conception of the brain and our relationship with the brain. Whereas Eisenstein’s intellectual cinema, focused as it is on the sensorimotor production of dialectical concepts, correlates with an understanding of the brain in terms of integration and association, that of Alain Resnais cannot be understood apart from new orientations in cerebral processes, what Deleuze elsewhere calls the indeterminate brain. Yet, in the end, Deleuze’s postulation of isomorphism between cinema and brain remains disturbingly one-sided; despite its crucial role in opening new possibilities for cinema, the brain on this account comprises nothing more than the passive object of a cinematic inscription ( Hansen 593).

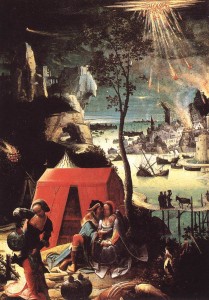

I include this long quote because it alerts the reader to the problem that Hansen experiences in gathering support for his argument about time in relation to video, HD or otherwise. Video is not the same as film and yet the dialogue remains framed in the discourse of film. The argument returns to several older discussions. The anxiety reflected here in which the insufficiency of transmission between the viewer and cinematic production and in the interstitial space between the viewed and the audience is essentially a more tempered rational attempt at a direct interface with the episteme. Strangely, it is one that was rehearsed by Antonin Artaud in his essays on the Theatre of Cruelty, particularly Metaphysics and the Mise en Scene, in which he attempts to find the limits of representation through textually unmediated mimesis. It is relevant here in Viola’s piece because the figures in Incarnation, do not speak and we are forced to deal simultaneously with the technological transmission of information and the presence of human representations. Artaud begins by discussing the dramatic sensorial elements of the painting “Lot’s Daughters’ by Lucas van den Leyden” to show how the mise en scene is able to exorcise the need for language through direct connection with the senses. Artaud dismisses classical theatre and abhors the psychological. He famously suggests that in an actor’s gesture of physical agony a type of transmission of affect will occur between him or her and the viewer, who in Artaud’s conception must be central to the action. The theatrical lineage is clear in the silent grimaces of Viola’s actors.

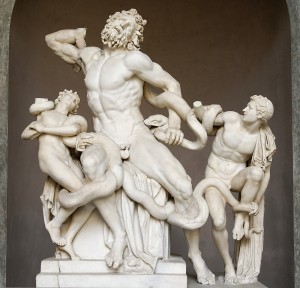

In respect to the duration of time in an image and even more appropriately the representation of human affect in time, one might as fruitfully turn to the discourse between Herr Winckelman and Gotthold Ephriam Lessing in his Laocoon: An Essay on the Limits of Painting and Poetry (1766). These gentlemen of the Enlightenment concern themselves with theatrical appropriateness of the representation, its degree, and the value of affect, in the Laocoon and this comes extremely close to Viola’s earlier work. In Viola’s Silent Mountain, 2001 , a man screams in modulations and then the video ends.

Winckelman is quoted with:

Such a soul is depicted in Laocoön’s face—and not only in his face—under the most violent suffering. The pain is revealed in every muscle and sinew of his body, and one can almost feel it oneself in the painful contraction of the abdomen without looking at the face or other parts of the body at all. However, this pain expresses itself without any sign of rage either in his face or in his posture. He does not raise his voice in a terrible scream, which Virgil describes his Laocoön as doing; the way in which his mouth is open does not permit it. Rather he emits the anxious and subdued sigh described by Sadolet. The pain of body and the nobility of soul are distributed and weighed out, as it were, over the entire figure with equal intensity. Laocoön suffers, but he suffers like the Philoctetes of Sophocles; his anguish pierces our very soul, but at the same time we wish that we were able to endure our suffering as well as this great man does” (7).

Winckelman might easily be contemplating a figure in Viola’s Incarnation, and this passage confirms a rationalist position in respect to the Laocoon, in that it is not excessive and alerts us to affect transmitted through sympathetic comprehension of a work of art, all of which apply to Viola’s depictions of trauma. Lessing draws pause:

…we would still have to consider, quite independently of these ideas, why the artist must nevertheless set certain restraints upon expression and never present an action at its climax (Lessing 19).

Lessing proposes that some representations are too extreme and must be reined in. There is a limit. Yet notwithstanding, in his disavowal of the propriety of full expression Lessing acknowledges that it is possible to show the climax of action.

Lessing’s essay attempts to discover the limits of painting and poetry in respect to the theatrical realm. Lessing breaks the elements of theatre into component pieces, speech is represented by poetry and the painting represents the sets, the appearance of the actors (without dialogue) and all the other visual constituents of eighteenth century German theatre. In this configuration a painting can stand in for a proscenium stage to offer Lessing the ability to examine the duration of perceptual time in a single image. The painting operates as a captured image, understood in the broadest sense as a snapshot, which both allows consideration of the time that precedes and informs the meaning of the image and the time that begins anterior to the depicted moment in relation to the viewer. The viewer in this relationship can also be understood to represent an audience member, who is an integral part of any theatrical process as there can be no spectacle without spectator. Lessing isolates the elements of text and visual to argue that a painting exists in temporal simultaneity:

I reason as follows; If it is true that Painting employs in its imitations entirely different means or symbols than those adopted by poetry –i.e. the former using forms and colors in space, the latter on the other hand, articulate sounds in time-if it is admitted that these symbols must be in suitable relation to the thing symbolized, then symbols placed in juxtaposition; and consecutive symbols can only express subjects of which the wholes or parts of which are consecutive.

Subjects, the wholes or parts of which exist in juxtaposition, are termed bodies. Consequently bodies with their visible properties, are the special subjects of painting.

Subjects, the wholes or parts of which are consecutive are generally termed actions. Consequently actions are the special subjects of poetry.

Yet all bodies do not exist in space only, but also in time. They continue to exist, and may at each moment of their duration, assume a different appearance of stand in a different combination. Each of the momentary appearances and combinations is the effect of the preceding one, and may be the cause of a subsequent one, thus forming as it were the central point of an action…(A Painter) can only make use of a single moment in the course of an action, and must therefore choose the one which is the most suggestive and which serves most clearly to explain what has preceded and what follows (78).

In his comparison between painting and poetry, Lessing suggests that figures depicted on a flat surface exist in relationship to time as happening in the moment of perception. Action, he suggests, belongs to the realm of poetry (language), because actions happen through time and language can accommodate the sequential claims of happening. Action happening through time might be seen as the way that video can interface with time to take over the role of speech. The consecutive nature of the moving image might be seen as doing the work of speech by providing the actions, to which the viewer supplies the language. Lessing’s exercise is only at the service of finding the theatrical limits of how a theatrical climax is perceived in relation to affect and catharsis. And this points back to the work of Viola, which in Incarnation’s repetitious loops enacts a climatic moment over and over. It is a circumstance fraught with linguistic challenges as Artaud recognizes and makes the claim for direct action and unmediated affect to connect with the audience:

I say that the stage is a concrete physical place which asks to be filled, and to be given its own concrete language to speak. I say this concrete language, intended for the senses and independent of speech, has first to satisfy the senses, there is a poetry in the senses as there is a poetry of language and that this concrete physical sense to which I refer is truly theatrical only to the degree that the thoughts expressed are the beyond the reach of the spoken language (37).

Metz understands this inherently in his observation about the real and the unreal, the material and the immaterial and how absence is doubled in film.

Thus far, I have only attended to the work entitled Incarnation and now I want to return to the gallery armed with these ideas, to revisit the pieces, because the show is diverse and draws from different periods. Immediately upon entry, one enters a full room installation, Pneuma.[x]

Amorphous images fill the walls, memory is evoked and an indistinct sound track implies sounds in the distance. The noise is neither diegetic nor non-diegetic, it ties and unties to the images, but one can never be sure because the images themselves, a house perhaps, a child maybe, never coalesce into concrete forms. The images operate in absence. They lack the real. The effect is pure theatre, unadulterated mise en scene. Again the structuralist elements are harnessed to the service of, in this case, a vague narrative. Apparently, in Viola’s view, the human condition is fuzzy around the edges and memory is weak, grey and out of focus. A guilty thought drifts into my consciousness; that his is not the romantic version of memory which improves the past in recollection, or draws the world into sharper focus and that in contrast with the other images in the gallery with their hyper clear imagery, this represents an attempt that didn’t quite come together as it should. I suspect that the artist’s intention and success are at odds and that the imaginative space left for the viewer in fact fills a vacuum in the artist’s conception. However, I am shortly vindicated in reaching for romanticism in the modern space of the gallery, when I find in the next room a smaller piece entitle simply Old Oak (Study),[xi] which shows a large tree and the play of a sunset as the light filters through the branches.

Web title, The Darker Side of Dawn, titled in exhibit Old Oak, (Study), Bill Viola, 2005. Color video projection on wall in dark room 128 1/4 X 228 inches, edition of 3. Photo: Kira Perov

It is quite lovely. It raises issues of nature and temporality and is surely romantically intentioned, since it was made for the operatic set of Tristan and Isolde in the project in which Viola collaborated with director Peter Sellers at the Metropolitan Opera in New York. It was not eventually used in the Wagner opera’s mise en scene. In the background lurks an anxiety about the easy admission of this “set piece” in to a show which makes claims for spiritual content. It is interesting to imagine that the tree was intended to fill the entire vast backdrop of the stage at the Met and this speaks to the developing potential of the video medium and its ability to transfer into the commercial realm. I have since learned that two giant-screen installations of Viola’s Mary and the Martyrs are planned for London’s St. Paul’s Cathedral later in 2011. Ruiz and D’Arcy tell, “Canon Martin Warner, Treasurer of St Paul’s Cathedral, says the new videos should attract some of the five million tourists who visit Tate Modern every year. ‘Art today captures people’s imagination in a way that perhaps narrative discourse doesn’t,’ he says. ‘The huge numbers of people that visit Tate on the opposite side of the Millennium Bridge from us are an indication of that fascination with…how you can express what is intangible but real and that comes very close to what Christian faith is all about.’ ”

In some ways this commentary clarifies my concerns about Viola’s use of video. It alerts one to a failure to grasp the potential of the medium. While I have my concerns about the content, they are my personal concerns and may reflect my tastes, biases and personal issues about trade and commerce in the arts in relation to religious imagery, but the deeper issue for those interested in media is the missed opportunity to advance the medium of video, which is as yet far from understood or fruitfully exploited. One might compare Viola’s use of video with the work of Joseph Nechvatal (who I disclose is my friend) and his attempts to penetrate the potential of the medium. Though his work is often politically charged and for the moment I reserve the right to set aside issues of content, his interaction with video attempts to understand the technology in relation to human life and therefore repels glib usage.

Other pieces in the Viola exhibition include more video images of figures who are passing back and forth through water in the fuzzy, white noise of the surveillance camera footage, or belong to another series in which slightly amorphous figures are formed and dissolve in points of light. These are the works for which the show is named. One such piece is therefore named Bodies of Light.[xii] The latter images are all ideally suited to the notion of the double negative, the unreal, the absent, because they are all images that speak of metaphysical passing, of dissolution, of dissipating light. This is possibly what is at issue in this use of video. Viola taps the inherent ability of the medium to fall apart. For as much as it can show profuse detail which is immanent in its digital mechanics, so too is it the most easily dissolved. The individual points of color and light eviscerate and nothing is left. Viola gives no language; the diegetic sound produced by the transmission, if you will, provides the soundtrack, reminding one of the absence of articulated sound. Water comes and goes from the passings, but the undecipherable sound that never coalesces into anything beyond a sensory experience, finally disappoints. The uses of video and high-definition digital technology in such a self-referential way that utilizes the aspects of the uncanny that are proper to the medium to invoke the uncanny seems somehow duplicitous. To restate Metz,

The imaginary, by definition, combines within it a certain presence and a certain absence. In the cinema it is not just the fictional signified, if there is one, that is thus made present in the mode of absence, it is from the outset the signifier (54).

Undoubtedly, the same may be said of video and that even more than film, this simultaneous presence and absence, together with the ability of video to show the world in durations that match, if not exceed, the amazement first elicited by Eadweard Muybridge’s revelatory photography.

Muybridge was known for his scientific clarifications of motion, and the chance to see what we do not know about ourselves and our world is undeniably useful, but the overlay of spirituality onto those images would be laughable. Why does the addition of water and light turn the Viola images into something that commands reverence and awe?

I recall public excitement when Stanley Kubrick succeeded in filming his candlelight scenes in Barry Lyndon due to his ability to press the medium of film and light further in the service of narrative. His achievement was to press the limits, rather than to exploit film’s natural qualities. Viola’s historical references and his historical usages are referential not only in content, but in cinematic usages and as I noted previously, when he taps the inherent qualities of video the results though startling and disturbing might depend rather too heavily on the titles and what the viewer is told is on display.

The limits of Video and the new media remain untested. For me, Viola does not press the limits of what might be done with these new potentials. In the gallery in the heart of the Chelsea art market, video remains simply a fetish object in limited editions.

[i] Venice Bienniale Bill Viola – Ocean Without a Shore – Venice Biennale 2007 Interview

[ii] While the problem of subjective versus objective viewing of art is forever problematic and deserves a nod at this juncture, let it not hijack the specifics of this discussion. Questions of textual support and “extra” information also raise another set of issues concerning the interpretation and discreet nature of an art work, or its tendency to slip into a maelstrom of possibilities.

[iii] Incarnation, 2008, Color High-Definition video on plasma display mounted on wall; two channels amplified sound 61.2 x 36.4 x 5 in (155.5 x 92.5 x 12.7 cm). 8:55 minutes

[iv] I use italics to alert the reader to its specific theoretical usage in reference to cinema and video.

[v] I uncomfortably note apparent race, only to point to the perhaps intended availability of universality.

[vi] Lacan discusses St. Teresa specifically and makes her the case to explain the infinite incomprehensibility of feminine non-phallic jouissance. Viola utilizes that feminine infinitude to draw in the viewer to theorize about God’s “unopenable box.” In other words, Lacan suggests one knows the box exists, but one can never understand it, unless one become a mystic too.

[vii] My insertion.

[viii] Hansen responds to a work entitled Anima (2000). The images are slowed so that the playback of one minute of footage extends for 81 minutes.

[ix] Aristotle’s Poetics Bk. V.

[x] Pneuma, 1994/2009, 14 x 20 x 20 feet (4.3 x 6.7 x 8.3 meters) room dimensions, Three channels black-and-white High-Definition video projected into three corners of a darkened, square space; three channels amplified sound. Continuous running.

[xi] Old Oak (Study), 2005, Color High-Definition video on LCD flat panel mounted on wall,14 x 24.8 x 3.5 in (35.5 x 63 x 8.9 cm), 30:16 minutes. Edition of 12.

[xii] Bodies of Light, 2006, Black-and-white video diptych on plasma displays mounted on wall 40.2 x 48 x 3 ½ inches (102 x 122 x 9 cm) 21:27 minutes, Edition of 7

Bibliography.

Artaud, Antonin. The Theater and Its Double. Trans. Mary Caroline Richards. New York: Grove Press. 1958.

Barthes, Roland. Mythologies. Trans. Annette Lavers. New York: Hill and Wang 1972.

Lacan, Jacques. The Four Fundamental Concepts of Psycho-Analysis. Trans. Alan Sheridan. Ed. Jacques-Alain Miller. New York: Norton, 1977.

Hansen, Mark. The Time of Affect, or Bearing Witness to Life, Critical Inquiry: Spring 2004; 30, 3: Proquest Direct Complete pg.584

Higgins, Kathleen Marie. Whatever Happened to Beauty ? A Response to Danto//1996 in Documents of Contemporary Art , ed Beech, Dave. Mit Press: USA 2009.

Lessing, Gotthold Ephriam. “Laocoon: an essay on the limits of painting and poetry.” Trans. Edward Allen McCormick. London: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1962.

Metz, Christian. The Imaginary Signifier, Psychoanalysis and the Cinema. Trans. Ben Brewster. Indianna: Indianna University Press. 1977.

Viola, Bill. Bill Viola: Bodies of Light, Press Release. New York: James Cohan Gallery, 2009.

Ruiz, Christina and Dave D’Arcy, “St Paul’s Cathedral hopes for Tate visitors with Bill Viola plasma screen altarpieces.” The Art Newspaper. Feb 10. 2011. <http://www.theartnewspaper.com/articles/St-Paul-s-Cathedral-hopes-for-Tate-visitors-with-Bill-Viola-plasma-screen-altarpieces/17814>