EARLY TATSUMI: The Push Man and Other Stories (1969)

Everyone has to start somewhere.

For Yoshihiro Tatsumi and Drawn and Quarterly that beginning was the collection of short stories titled The Push Man and Other Stories, an anthology of stories dating from 1969 which was translated and published by Drawn and Quarterly in 2005 [1].

It comes with a prodigious list of accolades. Chip Kidd calls it a “revelation” which “[peels] away the lacquered layers of Japanese social and sexual surfaces to reveal the elemental heart beneath, and with such fearless depth of feeling.” Paul Gravett proclaims Tatsumi “a master of frank, unsentimental exposés of the human condition”, and Jaime Hernandez suggests that “Tatsumi’s comics are clean and straightforward without pretentious tricks. Storytelling at its best.”

The evidence on the ground is less convincing.

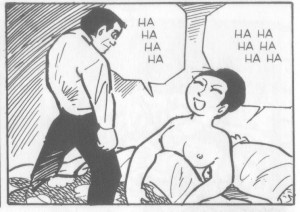

The drawings in this early collection are crude, inexperienced and laid down with the kind of haste which begets mistakes; these problems crystallized in a panel found on the fourth page of a story called, “Black Smoke”. Here an immense buxom woman reclines in bed laughing at her husband, a midget standing in the foreground whose height hardly makes up the upper body length of the naked female.

Not, sadly enough, a modernist meditation on the way the naked feminine looms large in the minds of all men, but a simple lapse in ability and attention to detail by an artist who has come to be known as one of the greatest exponents of the gekiga movement (if only in the West).

This is where it begins, a mixture of not so youthful ambition (Tatsumi was born in 1935) and hackery. Habituation to the author’s unchanging male perspective is the order of the day. The misogyny is laid down thickly with a trowel: a smörgåsbord of whores, unfeeling sluts, and deceitful and hectoring wives. This isn’t particularly surprising or disturbing on a moral level but ultimately deadening from an artistic standpoint, leading to rank predictability. To suggest, as Kidd does, that this brutish view of women is the “elemental heart” of Japanese society is nothing short of ludicrous.

You can understand where all this comes when you consider a book like Black Blizzard (1956), a comic from the prison escape genre created on the commercial treadmill. The arch lack of subtlety, the fixation on melodramatic confrontation and ridiculous coincidence, the barely digested tropes slapped on with a wild disregard for emotional or sensory engagement; all these now transplanted to early gekiga and designated realist stories (or perhaps a kind of comics vérité) on Western shores. They are, of course, nothing of the sort, being little more than a mixture of Tatsumi’s genre habits, his knack for tabloid sensationalism, and simple wish fulfillment. These are stories directed at the entertainment and arousal of boys and men, so tame and predictable in their reach for the extremities of human existence that they fail even in comparison to some of the children’s horror books of the time.

Certainly, it’s a question of interpretation. Deji Olukotun at Dejiridoo has the following to say on these elements:

“…I mentioned that Tatsumi concludes A Drifting Life just as sex enters his life. This makes it all the more striking that the short stories in The Push Man so often hinge upon sexual themes. There are steamy affairs, escort girls, abortions, and even sex slaves. Sex also does not occur without some awful, frequently fatal consequence. Tatsumi the man is creatively exploring a world that he ignored as a boy….That is not to say that the collection is lurid or prurient. The stories are tightly written, often concluding with the kind of ambiguous short story ending that only the best writers can capture.”

It’s not incorrect to suggest that Tatsumi’s stories are tinged with a certain ambiguity. The title story of the collection has a degree of vagueness about it, as does Tatsumi’s slight take on a transgendered love affair in “Make-Up”. Yet a summary of some of the denouements in this collection will serve to illustrate just how misleading Olukotun’s remarks are:

- In “Projectionist”, an exhibitor of pornographic films with a low libido finds that he is more aroused by crude drawings of women scrawled on a bathroom wall. He has marvellous sex with his wife after just such an encounter.

- In “Black Smoke”, an infertile, hen-pecked incinerator worker decides to allows his wife to burn to death in an accident.

- In “Test Tube”, a sperm donor attempts to rape a recipient when his semen is rejected following a lack of success with it.

- In “Pimp”, an ineffectual kept man is apprised of the limitations of his emasculating condition, and abandons his city girlfriend in favor of a country girl. He finds (and the reader is apprised of this in the most obvious of metaphors – the return of a caged bird) that he has simply exchanged one mistress for another.

- In “The Push Man”, an otherwise virtuous train push man finds that he has become a part of the on rushing crowd (a metaphor for a highly sexualized humanity) following a night of group sex.

- In “Traffic Accident”, a car mechanic who is enamored of a television hostess discovers that she has a partner and is of questionable morals. He arranges for her car to crash and kills himself upon the announcement of her death.”

- In Disinfection”, a man who specializes in disinfecting telephones wants to bring his skills to the fallen women of the streets of Tokyo with what I presume to be comic results (it’s difficult to tell since Tatsumi is a horrible comedian). The prostitute he engages refuses to be scrubbed and he placidly returns to his telephone cleaning activities.

That whiff of the EC Crime line (their linear structure, their preoccupation with twist endings) from these comics is quite real. Most of these stories have a firm finality about them which apprises the reader that a conclusion has been reached. Like the craftsmen of old, Tatsumi treasured clarity of narrative, emotion and intention above all else, frequently to the detriment of his shorter stories. Almost all of these follow a familiar narrative arc, from the introduction of the protagonist, to the delineation of his fetish or sexual hang-up, and thence to a conclusion wrapped in sex and death.

Tatsumi’s laundry list of inept metaphors is ever present: in “The Pimp”, the shadow of a bird cage is cast on the protagonist’s face in an effort to signal his entangled state.

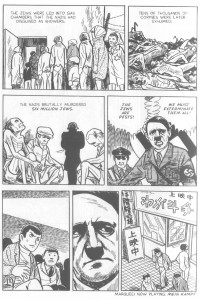

In “The Killer”, Tatsumi’s main recourse for demonstrating the state of mind of an assassin is to insert a page explaining (badly) the Holocaust and Hitler.

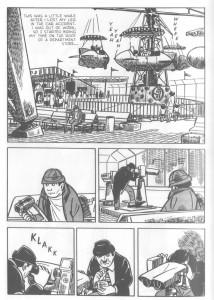

The characters which inhabit these early tales are caricatures, and the plots themselves read like 1 page summaries of The Postman Always Rings Twice. Most egregious of all is the story, “Telescope” which begins at the roof top amusement park of a department store.

The protagonist of the comic is an amputee nursing a crutch in his right armpit. Following the example of an elderly man, he uses one of the park telescopes to spy on a naked woman (who is seen willingly exhibiting herself) in the apartment across from them. He does the same the next day only to find the old man having sex with his young lover. He is relieved to find that the aged gentleman is as impotent as he is.

The young man is discovered in the midst of this indiscretion but, contrary to expectations, is asked by the elderly gentleman to spy on him again when he has another tryst with the woman. He is even paid in advance for his efforts. The old man is invigorated by this communal voyeurism and gives his mistress a royal screwing. When she is in a state of post-coital bliss, the old man looks back out the window to his witness and assistant. His sly look of triumph crushes the spirit of the young man who promptly hurls himself from the roof killing himself.

[One-legged, impotent man throws himself from building after seeing old man have sex]

The loss of limb experienced by the young man is a metaphor for his emasculation, that castration of youth conveyed so frequently in Tatsumi’s stories. One assumes that readers of the time were expected to delight in the kink of scopophilia, revel in the skilful mingling of sex and death, and meditate on that curious blunt anger directed at an older, corrupt generation.

The only correct response to this heavy handed study of despondency and sterility in this day and age is to burst out laughing.

Tatsumi’s “Telescope” is without a doubt one of the most cretinous depictions of humanity ever committed to a paneled page. Its sole worth can be found its central implication: the next time you see an impotent cripple walking past you, please remember to tell him to kill himself; a vastly more practical and beneficent solution than creating this comic in my opinion. This is the kind of story which any self-respecting cartoonist would pay his publisher to destroy.

Tatsumi has called the stories in this collection “only an introduction to [his] work”. We should add to this the considerably more candid disclaimer that these comics are largely of historical interest only.

* * *

LATER TATSUMI: Abandon the Old in Tokyo (1970)

“…these stories from 1969 are only an introduction to my work. The true scope of my work can be understood only after you have read my later stories.”

Yoshihiro Tatsumi in an interview with Adrian Tomine

In his pithy review of Yoshihiro Tatsumi’s Goody-Bye (1971-72), Bill Randall gave his final word on the comics of the noted mangaka:

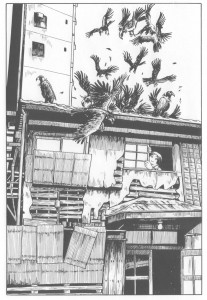

“Few Japanese remember the man who invented gekiga, the “dramatic” version of manga. Just two volumes of his solo works are now in print from Seirinkogeisha, the premiere (and small) avant-garde publisher. The trends in manga have led away from the ponderous, grotty style he pioneered…I once referred to Tatsumi’s stories as “vicious shorthand,” an apt phrase that is not praise…That is not to question their place in history. Tatsumi gave the keys the Garo artists of the 70s, like the Tsuge brothers and the “three retainers” of Shinichi Abe, Ouji Suzuki and Masuzou Furukawa. Their works offer more complexity and range, and have thus been remembered. Tatsumi’s work lacks their virtues; nonetheless, Good-Bye shows exactly why he should not be forgotten….His accomplishment lies in his images, none better than in “Sky Burial.” The story follows a man who, hearing of a Tibetan tradition of sacrificing the dead to vultures, is hounded by birds. The story’s final image, a full page worthy of framing, says more than all the plot and narrative before it.”

Where The Push Man and Other Stories collected the works of a young artist grasping at something unattainable, the collection of stories titled Abandon the Old in Tokyo signal Tatsumi’s development into a more rigorous artist, a development which would find its ultimate distillation in Good-Bye.

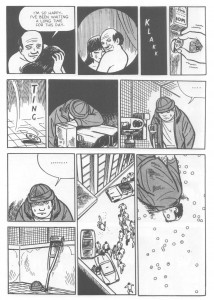

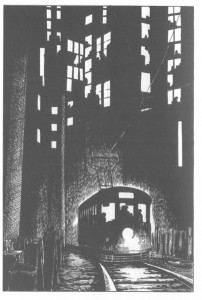

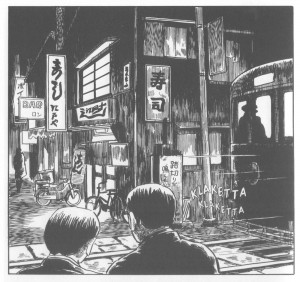

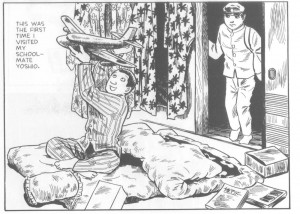

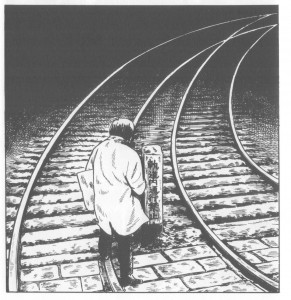

One of the finest expressions of this can be found in his story “Forked Road” which dates from a year earlier than Good-Bye. Here we find skilfully worked scenes of a tram car trundling through the streets of Tokyo, the office silhouettes embedding us in a world both familiar and real.

The city streets are as well defined as ever…

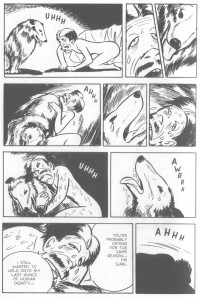

…and Tatsumi frequently shows a deft hand at narrative, pushing his readers through pages of drawn out dialog with skilful shifts in perspective. For once, the gaze is not that of an artist invested in titillation and easy emotional responses, but vigorous and animalistic; everything suggesting movement, grasping, and sweat.

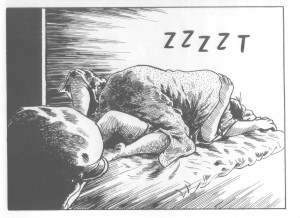

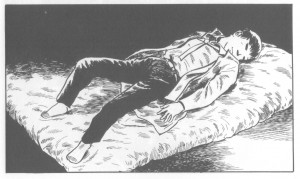

The image of a mattress is reinforced throughout by the author, and is to be compared with an earlier panel showing the protagonist sprawled in a drunken stupor on the same; …

…the fork in the road between childhood…

…. and maturity; between union and solitude.

There’s less of that resort to genre shorthand, less of that imposition of a definitive conclusion or statement so typical of his early work.

The sensationalism also develops a bit more bite. In “Unpaid”, a former company president is forced to act as a dog in front of his creditors and finally seeks solace in the orifices of his pet bitch. Not bad if a bit obvious as a short portrait of degradation, but of little lasting worth compared to a more gentle film like Kurosawa’s Ikiru (which also examines a company man at crossroads).

Not all is well with this collection of stories. Repetition is the unforgiving mold which corrupts many of Tatsumi’s tales. Those tic and habits formed through years of hard graft remain as inescapable as ever. The subjects of voyeurism and lust are reiterated ad nauseum, as are the cumbersome centrally placed metaphors so typical of his work (trams and penetration; the tyranny of the mob as symbolized by a troop of feral monkeys in “Beloved Monkey”).

Nevertheless, the publicity which has followed Tatsumi’s rise has been enough to convert critics of every stripe. “Starkly beautiful…revelatory…fearless” cries The Village Voice. “Marvelously evocative” intones Publishers Weekly. James Defebaugh of The Examiner is quick to praise Tatsumi’s repetitive figure work as a bold artistic move:

“Many of the differently named and circumstanced protagonists, for instance, look more or less the same. There is also a recurring young, beautiful, round-haired female type who appears in many of these stories. While some readers may be willing to dismiss this as artistic laziness, it’s very obvious from Tatsumi’s drawings as a whole that there’s nothing lazy about them.” [2]

An examination of Tatsumi’s comics tells us otherwise. This facet of Tatsumi’s art plagues the majority of mangka who produce work on a factory scale. Tatsumi was no different from those individuals, and there is little need to give him credit where none is due. The familiar figures which recur and populate Tatsumi’s stories are well delineated through years of practice but their repetition is due to the limitations of his creative abilities and imagination; a failure to move beyond what remains totally acceptable in modern day manga.

Tatsumi’s stories are frequently compared favorably to those of his Western counterparts from the same era, yet a comparison to the literature and films preceding his moment in history is not only fair but far more telling.

The title story, “Abandon the Old in Tokyo” corresponds in theme to Ozu’s Tokyo Story but is so enraptured with melodrama, coincidence, and excess that our engagement and empathy is stifled. Tatsumi’s story is about the repulsion and sense of duty attached to the “old” things of his culture; not only the elderly mother who the protagonist has to wash and take care of, and who he sees all too clearly as a neglectful parent, but everything associated with that world. There’s a wrecking ball destroying old tenements to open his story and a spanking new Shinkansen to close it. The intervening symbols are equally tedious and obvious; the insights into a culture seemingly devoted to the concept of filial piety superficial and not worth mentioning. “Metaphors like cudgels” is how Bill Randall puts it in his review of Tatsumi’s later collection, Good-bye and not in a good way.

“The Hole” (a story concerning a man trapped in a hole by his jilted wife and a disfigured misandrist) pales in comparison to Kobo Abe’s The Woman in the Dunes (1962) in imagination, resolution, and daring. Tatsumi’s narrow and poorly conceived views of “fallen women” [3] can only be deeemed an embarrassment if compared to Mikio Naruse’s portrait of Keiko in When A Woman Ascends the Stairs (1960). These tales are neither close enough, true enough, sad enough nor vile enough to shock us from our modern stupor.

Despite the last decade of progress, an excessive investment in the worth of comics has led artists and critics to cling to any straw presented to them however frail. The elevation of the manga of Yoshihiro Tatsumi in the West represents an instance of this useless clutching. These stories simply cannot bear the weight of a truly critical reader’s expectations. To suggest otherwise is to do the art form a disservice.

NOTES

[1] From Adrian Tomine’s introduction:

“…Mr. Tatsumi has produced a mind-bogglingly immense body of work. So this will be a selective survey of his best work, beginning, at Mr. Tatsumi’s request, with the year 1969. Our hope is to release one volume per year, each focusing on a single year in Mr. Tatsumi’s career.”

[2] From an interview with Yoshihiro Tatsumi conducted by Adrian Tomine.

AT: Can you talk a little about this sort of archetypal Tatsumi character? I assume that he’s not supposed to be the same person, but the protagonist in a handful of these stories (for example: “Beloved Monkey”, “Abandon the Old in Tokyo”, ‘Eel”) is drawn in a similar manner. Do you think of him as the same person, or is he, perhaps, simply representative of a certain type?

YT: The character that looks identical throughout my work is, of course, different in each story, but he essentially represents my view. You could say I projected my anger about the discrimination and inequality rampant in our society through him. Do you see why my protagonists couldn’t possibly be handsome?

[3] Dreadful as some of Tatsumi’s early works are, his comics have nothing on a film like Kenji Mizoguchi’s Women of the Night, a hysterical, moralistic potboiler which will leave your jaw on the floor. Kinuyo Tanaka (as the widow-prostitute Fusako) under the direction of Mizoguchi becomes the Chaplin of unintentional, neorealist comedy in this movie. Read the solemn liner notes of the Eclipse edition DVD for yet more laughs.

I couldn’t agree more. The reception of these books in America has been rather disheartening. I mean, they’re so obviously hyperbolic and simplistic that one would think it would be… well, obvious.

A Drifting Life perhaps less so, but that’s one straight-up boring and unenlightening book.

I’ve yet to see a convincing argument for the greatness of Tatsumi’s work. And I agree with Matthias, A Drifting Life was so dull and to me neither succeeded as autobiography nor as comics history.

Gary Groth wasn’t that taken with Tatsumi either, right? And I think Bill Randall’s expressed skepticism as well (unless I’m hallucinating that….)

Suat-

Although I’d agree with you about the crudity (rushed nature?) of the artwork in places, and the one-note effect that reading a lot of these stories in sequence can have, I disagree pretty strongly with your overall conclusions as to the quality of the Push Man. A lot of the material borders on cliche, yes- but it’s cliche wielded like a cudgel. I happen to think this is a good thing- or that it can be, at least.

The stories in the Push Man are almost uniformly bleak, but to me anyway, bleak in a way that speaks really clearly to a certain kind of person that feels untethered from their society, who has no place to turn and no purpose to bury themselves in. Often times in the stories the main character will find that purpose in some unlikely place- on the walls of a urinal, in spending his pension money that he’s gained from mutilating himself- only to find that even that isn’t enough.

I don’t know if it’s just really strong identification or recognition at work for me, but the stories in the Push Man seem very real to me, even in their hyperbole. And the crude rendering serves to heighten that sense of griminess and age.

Also curious what you think of My Hitler, the only story in the book to break the 8 page mark, and the only self-published one in the bunch.

Aah; I see you quoted Bill; that’s what I get for commenting before reading the whole thing closely…

Very definitive, Suat. And congratulations on the new site!

I’ll add that Tatsumi’s story in English is about marketing and a lack of context. D&Q has marketed Tatsumi and “gekiga” very well, though it’s worth noting that the term “gekiga” first appeared in issue 12 (1957) of “Machi,” a rental manga, as a blurb on a Tatsumi title page: “GHOST TAXI” has the title, “Mystery Gekiga” (Encyclopedia of Contemporary Manga, p. 62). It feels closer to “Ghost Taxi Mystery Theater” to me than, say, an equal of any of Kurosawa’s gendai-geki or jidai-geki from the period. Decades later, the gekiga “brand” and an unimpressive body of work have Dwight Garner in the NYTimes saying of Tatsumi’s work, “It’s among this genre’s signal achievements.” (At least Gary Groth, to his credit, never bought it: “I usually only interview artists whose work I like, and I didn’t feel entirely comfortable interviewing Tatsumi. I was troubled by a number of tics that comprised the backbone of Tatsumi’s aesthetic…” TCJ #281, p. 37)

I wanted to add a footnote from a couple Japanese sources: The Encyclopedia of Contemporary Manga, 1945-2005 (Shougakukan), ends its sole entry on Tatsumi with with the fairly tepid, “Recently, his esteem has also grown abroad.” (Just before its publication, in 2003 AX #34 presented an unpublished Tatsumi story with a full-page ad proclaiming his work would be published in the West. AX is from Seirinkogeisha, now the Japanese publisher of his work as well as others in that tradition.)

The rest of the encyclopedia’s entry was a plot summary of the short story “Man-Eating Fish” and a sentence noting how Tatsumi “deeply expressed the dead-end circumstances of men living in society’s lower reaches” (clunky offhand translations mine). A true documentary of those men would be more interesting, but he prefers tidy immorality plays. Even his images, some fine examples of which you selected, no more than equal those of his peers. It’s telling that another Japanese work, the critic Natsume Fusanosuke’s formalist critique “Why Is Manga Interesting,” chooses artists like Nagashima, Tsuge, and Sait? in describing the old gekiga style, but not Tatsumi. Would that D&Q had published five volumes of Shigeru Mizuki and a slim one of Tatsumi. The rest of their gekiga line’s quite strong, but the word’s not very helpful, and the brand even less if it means Tatsumi’s the touchstone for excellent artists like Ouji, Sakabashira, and Mizuki. Mizuki’s a giant; Tatsumi was forgotten until D&Q picked him back up. The result has been a distorted image of his work’s importance more than a valid reassessment, one that even the New York Times repeated uncritically.

Oops. That should be “Saito,” link: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Takao_Saito

Also: would Tatsumi’s stories work better as a one-man show in which the performer yells a title and then kicks the (lone male) audience member in the nuts?

“LIFE IS SO SAD!” kick

“PROGRESS IS WONDERFUL!” kick

“GOOD BYE!” kick

Goddammit. I just did a google search for your name and Tatsumi, Bill, to read your review, and what do I find but an eerily familiar FIRST SENTENCE of your review of Goodbye. “Using ink and metaphor like cudgels…” Sound familiar? It should, as I typed something very similar in a comment today! I feel like an idiot. Obviously your review made an impression on me, even though I didn’t remember having read it. Please accept my embarrassed apology.

Don’t be embarrassed! In medieval Europe scholars would read important works over and over to etch them into memory.

I am honored to be your neurons.

Bill: Thanks for all the information! That second comment is pretty mean. Tatsumi has a a pretty big audience in the West, right? A Drifting Life is a huge seller and it won a Tezuka Award to boot if I remember correctly. Unfortunately, I think his fiction is better than his non-fiction…

Sean: I can definitely see where you’re coming from, but I could only overlook Tatsumi’s cliches and somewhat bland rushed art if the narratives showed a keen grasp of that segment of society and the emotional turmoil of individuals at the end of their tethers The art completely fails to deliver on the latter aspect in my opinion. To do that it would have to be more raw, more angry, more direct, not merely rushed and slipshod. It simply can’t hold its own if placed beside the bleak vision of reality presented in the Dardenne Brothers’ Rosetta, the histrionic yet affecting plot of Yu Hua’s To Live, or even the immediacy of a hundred year old novel like Knut Hamsun’s Hunger. The notes which Tatsumi strikes in The Push Man & Other Stories seem not only repetitive but “false”. The emotions which drove these stories may have been quite real, but the fast paced narratives and the baldly stated passions communicate the excitement of the tabloids rather than the heartfelt anger or depression he desires as an artist. Of course, your mileage may vary but this impression (born of my personal make-up) is all that I have to go on.

I’ll have to reread My Hitler later today. It didn’t really leave any firm impression apart from the plotline. Less fixation on transposing genre tropes to “reality” certainly but I didn’t feel particularly moved by it.

May I conclude, then, that _Rosetta_ (your mag’s title) was an homage to the Dardenne brothers? That’s very cool!…

Eh, sadly no. That would be too presumptuous, and it didn’t even have the right aesthetic for that comparison. No, the title was in reference to the stone (where it was found and the history surrounding it). Anyway, the film is so depressing that I don’t know if I want to rewatch it (probably will at some point though).

Suat, fair enough. How about a two-man show with a huge audience, then? Just a thought on looking back at this cruel nihilism.

On the art, a “more raw, more angry, more direct” art might look like Takashi Nemoto’s chaotic work. Tatsumi’s drawing style seems cautious to me.

>baldly stated passions communicate the excitement of the tabloids rather than the heartfelt anger or depression he desires as an artist.>>

I just took another spin through the first few stories of the volume and I can definitely see your point. I’m pretty sure the (literal) tabloid nature is born out by at least one interview he gave, actually- saying something along the lines of the topics of various stories being influenced by newspaper clippings. I think the difference for me is two-fold- I admire the bleak outlook itself, for how infrequently those kinds of attitudes are portrayed, and so I think I’m willing to forgive more of the failings. This could also be because I’ve been exposed to less of the material from this time period and genre than you and Bill have.

Secondly, the stories that really get to me manage to brings some weight to the less successful ones, possibly because of the similarities in tone and subject matter. I brought up “My Hitler” not only because it’s my favorite in the first book, but also because it has a kind of quirkiness and unexpectedness to it that’s less common in the other stories. The weirdness of the relation to the rat, the rat’s behavior, the analogue between rat and wife. It also benefits from having more pages, and so it feels a little less like a stick of dynamite- not having only eight pages to work with, Tatsumi seems like he doesn’t need to rely on an emotional explosion to bring resolution- the story gets to be smaller because of the increased page size.

Bill- thanks for drawing attention to the upcoming Mizuki release from Drawn and Quarterly- I actually wrote about the single page from that book represented in Manga! Manga! last month, and stated my desire to read the whole thing- little knowing that it had already been announced for release! Really looking forward to it. Now if some brave company will pick up Matsumoto’s “I am a Man”…

Yes, as you indicate, a significant problem with the stories in The Push Man collection is that need for “an emotional explosion to bring resolution”. It’s quite possible that the times didn’t allow for anything else except this kind of narrative, but there’s also the failure on Tatsumi’s part to realize that his stories didn’t need that linear structure, or even any kind of explosion or resolution.

As for “My Hitler”, I’ve had a look again. A synopsis since I didn’t cover it in the article above: a man begins to identify more and more with the form and qualities of a rat that is infesting his apartment: the cooped up living conditions; the oppression of the city and its inhabitants which make him want to seek darkness and seclusion. The rat begins to manifest itself in his life and even begins to act like his wife (cuddling up to him, occupying a seat cushion, and attacking his mistress). The final scene is of him deserting his flirtatious girlfriend (a bar hostess by trade) in favor of the rat who has just given birth.

So a bit like Kafka’s Metamorphosis less the physical changes. More hopeful in its denouement as well (none of the baby rats look like Hitler). Certainly superior to many of the stories in The Push Man anthology but also showing some of the quirks found in that collection and the one from 1970 (I think it’s similar in form and content to “Pimp” and “Abandon the Old in Tokyo” particularly in his tired use of metaphor). I feel it’s less interesting than “Forked Road” and suffers from that lack of subtlety typical of Tatsumi. I think we should remember that the comic was written and drawn in 1969, years after the publication of major novels like The Makioka Sisters, No Longer Human and various short stories by Akutagawa (the list is longer but why bother). There are also a host of fine films by the directors mentioned above. The Tatsumi comic just doesn’t seem like anything special. It’s better than his earlier stories but I don’t see much beneath the central conceit. It seems hollow (emotionally and intellectually) and largely unmemorable to me.

Pingback: New manga considered, Tatsumi reconsidered « MangaBlog

Suat- Thanks for the list of books and movies to check out. Other than Mizoguchi, I’m not familiar with the other artists- looking forward to checking them out.

Sean: Ozu Ozu Ozu.

Also, Ikuru.

Derik- do you mean Ikiru, the Kurosawa movie, or Ikiru the Russian director? I’m very fond of the first, and have no exposure to the second.

Oh, sorry I meant Ikiru.

And while I’m tangenting on Japanese art… the author Kawabata.

Ng Suat Tong – Anyway, the film is so depressing that I don’t know if I want to rewatch it (probably will at some point though).

Rosetta can be seen here. I didn’t find it that depressing. Bleak but not as unpleasant as something like “The Wages of Fear” or “La Strada”

‘La Strada’ wasn’t unpleasant at all: it was touching and beautiful. Nor, really, was ‘Wages of Fear’, a classic adventure story.

I see Ikiru having less in common with “The Push Man” than other Kurosawa films, specifically “Drunken Angel”, which has the griminess and the unrelenting tone without the more obvious (and public) redemption in Ikiru. Anyway, I love them both, and most of the Kurosawa movies up until the 60’s.

If only Tatsumi had been as biting and passionate as Kurosawa was on “Drunken Angel,” which is arguably one of the all-time best Japanese screenplays. Whether Kurosawa was optimistic or not, at least he was always a humanist. One could hardly say the same about Tatsumi and his monotone stories.

i don’t remember drunken angel all that well, but for comparable kurosawa the first that came to mind was high and low. in terms of nihilism i’m also thinking of oshima’s earlier, less experimental films like naked youth and the sun’s burial (especially the latter: oshima’s postmortem on ‘the sun tribe’ depicted in crazed fruit?)

those are all about young nihilists though. when i think of tatsumi i think “dirty old men.” i agree that the differential between push man and its praise is hyperbolic. this essay is a good antidote to that.

Pingback: Links: Is Tatsumi Overrated?

The film comparisons bring up some interesting parallels–

1959-60:

Ozu’s career is winding down, the Japanese New Wave is ramping up, and Kurosawa’s between Hidden Fortress and Yojimbo. The year also saw huge leftist student & labor protests against the Japan-US Mutual Cooperation Treaty, a political event with a long shadow.

Meanwhile, Tatsumi, his brother (Shouichi Sakurai, who drew manga in a gag style), and a few others formed Gekiga Koubou (Gekiga Workshop) in ’59; he’s 23 or 24. It’s a young punks’ jab at Tezuka in a throwaway kids’ medium. Takao Saito joined quickly after, and by ’60 Tatsumi had left and Saito had taken over, renaming it Saito Productions, of course.

1968-73:

By now the Japanese film industry had peaked and begun to decline. Kurosawa’s fruitful period is over, TV has strangled the industry, and Nikkatsu has even given Seijun Suzuki the boot. For the leftists, the Marxist epic Kamui-den winds down in Garo in ’71; in ’68 Touei Douga releases “Hols, Prince of the Sun,” whose production saw labor strikes that included a young Hayao Miyazaki; and best of all in the epic noise band Les Rallizes Denudes, whose bass player helped hijack Japan Airlines Flight 351 to get to Pyongyang in ’70.

Meanwhile Saito Productions has debuted GOLGO 13, which has sold 200 million copies and is still running. Tatsumi’s stuck in Garo, which sells little, doesn’t pay, and lets him do what he wants.

But by October ’73, he’s got a short story (“Woman of Sapporo”) in Garo. It’s drawn from headlines about “coin locker babies” with a clumsy, obvious metaphor at the end. He’s just 38, has lived through a war, poverty, and reconstruction, but even the tumultuous years since coining “gekiga” figure little into his work. All his characters are trapped in their own obsessions, just as he’s trapped in his own artistic rut. Next to his story, Shinichi Abe’s “Tomato” is a humane look at sex and human interaction. Abe’s just 23, but the generational gulf seems huge. I can’t help but see Tatsumi as an artist who got stuck while the world, whether in Saito’s financial success, political turmoil, or younger artists’ creative innovations, passed him by.

Ah yes, the misogyny is blindingly obvious in his work. A big turnoff for me.

Bill- I’m confused by your repeated references to Takao Saito. I realize they were contemporaries, who knew each other and worked together, but are you suggesting that Saito’s artistic legacy or worth is greater than Tatsumi’s, and that is born out by the material? I’ve only read two volumes of Golgo 13 (two of the mid-eighties vanity releases by Saito Productions) , but those two volumes don’t give me any indication of some kind of larger cultural relevance. They seem like real simplistic adventure stories- a colder-hearted James Bond placed into different adventure scenarios in various exotic locales. Would you rather read a volume of Golgo 13 than another collection of Tasumi short stories?

Also, as far as relentless Kurosawa movies, I’d add Stray Dog to the list.

Sean, I don’t want to read either one again, but with the right crowd and some bourbon I might enjoy a Golgo 13 movie. I’m interested in “gekiga” as a term and category. It’s an old if important style in Japan, but right now in English people tend to use it as a stand-in for “graphic novel.”

For the style, gekiga had its boom in the early 60s and began to fade in the 70s. Its influence can be seen in the lurid, “adult” bits in late Tezuka as well as alt-manga like AX. Tellingly, the Japanese Wikipedia article focuses on the gekiga style of drawing. Gekiga artists used the G-pen, but when people saw Katsuhiro Otomo’s thin lines from the maru-pen (a thin crowquill, sold by Nikko in the U.S.), it was all over.

So why harp on Saito? Of Gekiga Koubou’s members, only he and Tatsumi are notable. Does Golgo 13 fit in D&Q’s gekiga line? No! But it defines the genre perhaps more than Tatsumi. Personally, I believe that Tatsumi’s invention of the term and group membership with Saito mean less to the genre than Sanpei Shirato’s work. His Kamui-den is gekiga’s key work, and he began Ninja Bugeicho in 1959.

That said, I don’t blame D&Q’s marketing, though I hope they get past Tatsumi. It was good branding, and it brought Suzuki Ouji, Susumu Katsumata, and Imiri Sakabashira into English– amazing! But some Nouvelle Manga artists and other, newer manga fit their sensibility better than fusty old gekiga. Half their manga line is Tatsumi. Yuck.

There. I wrote a couple of awful articles on gekiga way back before I knew anything about anything, so I hope this absolves any sins within.

PS Does anyone have a table of contents for “A Single Match?” I have four volumes of Ouji, but lack “Tokyo Good-bye” and some other shorts so I’m thinking of ordering it.

PPS Amazon.jp shows Tatsumi has a new book out as of last October– “Gekiga Living.”

Sent you a scan of the Single Match contents page, Bill.

Thanks! No Tokyo Good-Bye, unfortunately. No Motorcycle Girl, either? Hmm.

You’ve made a very solid case here, but you’re arguing a completely different set of priorities of merit. In response to claims of “clean and straightforward without pretentious tricks” and “frank, unsentimental exposés” you’ve pointed out the crude drawings and brutality which are the very foundation of that lack of pretense. They aren’t perfect stories, but that’s not the point. For many fans, that lack of perfection is much of the point. Whether he’s a true blue indie darling or a failed commercial artist, the fact also remains that he did find his niche and worked within it to the best of his abilities and those abilities are par for the indie circuit.

And I’m sorry, but I find it a bit tactless that this article responds to supposed failures in interpretation by attacking the artist himself. Tatsumi holds no illusions about his ability. You chose to question Tomine and the fans by attacking a man who likely agrees with most of your points.

I think it’s quite clear from the progression in Tatsumi’s art over the short period from 1969 to 1970 (and even in Good-Bye from 1971) that he was striving for a kind of technical proficiency. The crude drawings are a result of deadline pressures and, perhaps, unpolished skills. They don’t communicate bristling anger or vitality so much as ineptness. My assumption is that the quotes from Paul Gravett and Jaime Hernandez are proffered in relation to Tatsumi’s storytelling choices and not his drawing abilities. That is, straight narratives depicting the very edges of society and human existence. What I’m suggesting is that neither is the case. The narratives may be uncomplicated but they’re not derived from life (or a lack of pretension) but from genre conventions. The “brutality” is not realistic but proceeds from his naiveté, and an attraction to sensationalism and fantasy rather than “frank, unsentimental exposés”.

Finally, I’ll need to know which particular attacks on the artist you are referring to. Whatever Tatsumi’s feelings about his comics, his actions speak far louder than his words in that he allowed these middling comics to be republished in the first place. Far better to focus on the work from late 1970 to 1971 and , even then, much more selectively. As Bill Randall suggests, a systematic reprinting projecting like that undertaken by D&Q should be reserved for artists of a much higher caliber (granted that it was an excellent commercial decision on their parts).

Hey there.

I have to say I don’t agree with your opinions on Tatsumi.

I don’t think that lacking subtlety is always a shortcoming and in his case it just makes those short stories much more affecting.

To continue with the film comparisons, I enjoy much more Funny Games by Haneke that his later movies, just because it has much more visceral impact (don’t know if that makes much sense…) than stuff like that Caché (Hidden).

I seem to always see that the subtlety/obviousness dichotomy translates in critical lingo as good/bad and frankly that vision of things looks to me like being really cliched.

(This is not directed just to you, it’s an opinion I have on this general trend in criticism. I mean, I can totally accept that some people view things that way, but when you read subtlety always thought as a quality and obviousness always as a fault it really gets boring. Honestly, sometimes it can be a good thing, like in the best horror movies or rock music.)

There’s every reason to believe that you are in the majority as far as your opinion is concerned.

However, it goes beyond a lack of subtlety as I’ve stated in the article above. Even if we choose to concentrate on that point, I would suggest that Tatsumi’s brand of clarity is clumsy and frequently tepid resulting in manga which are dull and flat (and therefore nothing like Haneke’s Funny Games which I don’t find as palatable as you do).

Consider a contemporary of his like Umzeu Kazuo. There’s absolutely nothing subtle about Umezu’s manga and yet there’s that jolt with many of his comics, as if you’re peering into the deeper reaches of a very strange mind. It’s a unique and exciting vision. You don’t get that with Tatsumi who is largely earnest and derivative. This is what I meant when I compared his work with some of the children’s horror manga of the time. It’s pallid by comparison.

Oh, Ok then. When I read your post your opinion seemed a bit more one-sided then now, after reading this answer. Thanks for replying.

It’s funny because I had the opposite response to his comics. I really connected to his storytelling and artwork, but I’ll agree that Tatsumi’s stories got better in the following volumes.

As for what I said about Funny Games I didn’t meant to compare it directly to Tatsumi’s work, it was just to give an example of someone that, in my opinion, got worse with more subtlety added to his work. But yeah, Funny Games and Tatsumi have nothing in common.

“My assumption is that the quotes from Paul Gravett and Jaime Hernandez are proffered in relation to Tatsumi’s storytelling choices and not his drawing abilities.” – Right, the storytelling takes priority over the drawing ability. I don’t disagree with your points, I just think Tatsumi fans enjoy the work despite everything you’ve pointed out here. I don’t think anyone is being tricked, A Drifting Life comes right out and tells you what movies he was watching at the time he wrote which stories.

As for attacks, I’d say “hackery” is pretty strong. If you don’t think D&Q should be publishing Tatsumi, why not call Tomine a hack publisher? You have no problem calling an artist a hack for failing to travel back in time and live up to the hype, but you can sit there and praise Drawn & Quarterly for profiting off it? Randall’s article was a critique of the artist anything he had to say was appropriate. Your article Reconsiders (the popular interpretation of) Tatsumi and blames Tatsumi for failing to live up to those expectations. I’m sorry if that wasn’t your intention, but that was my read of it.

“…but you can sit there and praise Drawn & Quarterly for profiting off it? ”

I assure you, that wasn’t praise. I have no interest in praising publishers for profiting from mediocre manga. That was a mere statement of fact. Publishing Tatsumi has been a wise business decision for D&Q which in this case coincides with their aesthetic preferences.

I don’t know if the description of Tatsumi as a hack is strong, but I think it’s accurate as far as many of the early works in The Push Man collection are concerned. How else would you describe commercial work pushed out at speed to earn bucks? There’s nothing wrong with doing this kind of material to put food on your plate but don’t expect me to glorify it.

“Your article Reconsiders (the popular interpretation of) Tatsumi and blames Tatsumi for failing to live up to those expectations. I’m sorry if that wasn’t your intention, but that was my read of it.”

I’m not blaming Tatsumi for anything expect producing bad to mediocre art. I am blaming the critics for exaggerating the excellence of these comics.

As for attacks, I’d say “hackery” is pretty strong. If you don’t think D&Q should be publishing Tatsumi, why not call Tomine a hack publisher?

D&Q are definitely not hack publishers. But Tomine is definitely a hack artist. He’s a lightweight. The less said about Shortcomings, the better. And his contribution to Kramer’s Ergot 7 was pretty terrible.

Ok, I can see where you’re coming from a bit better now and I think I read an unfair and harsher voice than intended in your article. Sorry about that.

Logically though, I just don’t think the artist’s ability has as much bearing on the problem as marketing and interpretation.

Steven-

>>But Tomine is definitely a hack artist. He’s a lightweight.>>

Well, obviously mileage may vary, but I love to pieces about half the stories collected in “Summer Blond,” but like you, am less than fond of the unfortunately named “Shortcomings”. It’s interesting that the short length of the stories in Summer Blond seem to work for them, in that they suggest a whole host of themes and feelings by implication, whereas the comparatively lengthy Shortcomings feels to me more hollow and less nuanced and suggestive.

I realize I am commenting on a two-month old post, but I just now read it.

I agree with the basic crux of this analysis of Tatsumi. I think it is harsh but fair when it comes to metaphor and sexual values. In that era of Tatsumi’s work every oblong is a phallus and every hole a vagina, no doubt, and the misogyny is unmistakable.

Given this – given that Tatsumi’s work is unsubtle – I have to say your review is about as obvious as Tatsumi’s work. I sympathize with the desire to serve up a corrective to the promotional garbage that fills the press, but you are fighting straw men. I am not sure if you are saying much more than what any of us who have had doubts about Tatsumi’s glory have thought at one time or the other.

You were fairly generous about the menstrual flowers in Tsuge’s Red Flowers. Why is it that clichéd sexual euphemisms are okay in a pastoral “literary” genre but not in pulp? Is the problem that the cicadas and babbling brooks are peeled away?

Also, on what basis are Tatsumi’s drawings “crude” and “inept”? For the most part (some exceptions), they seem pretty finished to me, and work perfectly well for what he was trying to do. “Unpolished skills?” He was a 15-year veteran in 1970.

“A failure to move beyond what remains totally acceptable in modern day manga”? You mean manga then? If so, tell me who was doing stories like Tatsumi’s in 1970, aside from Tsuge. Second, Tatsumi was black-listed by Shonen Magazine, supposedly (according to Tatsumi in “Gekiga kurashi”) after their print-run fell after publishing one of his works) – clearly he was not “totally acceptable.”

Also, “Tatsumi was no different from those individuals (the factory mangaka)”? Just on the basis of a lack of character types? I think you also mention pressing deadlines as a reason for how the work looks the way it does. I doubt it. At this point, he was writing for very few weeklies (this changes in the mid 70s, after the period in question). An artist like him with a 15 year career, having produced hundreds of pages a month for many years, do you think writing one 20 page story per month was rush work? At least be generous enough to assume that the artist knew what he was doing and had complete control over the product. He might not have been a poet or a Kojima Goseki-caliber draftsman, but he was also not an amateur.

Again, I sympathize with your basic distaste. But not with the venting.

Ryan:

Thanks for taking the time to comment. Tom Gill means to reply to your comment on his Tsuge/Tatsumi post but has been tied up.

You ask on what basis are Tatsumi’s drawings “crude” and “inept”. I think a number of the images presented in the article above suggest a rushed quality – the second image from the top and the pretty abominable depiction of the Holocaust to name just two. Surely you can see the arch difference between the work from 1969 and 1970 in terms of technical polish?

As to my preference for the “menstrual flowers” in Tsuge’s Red Flowers, why does any reader prefer one metaphor over another? One could posit a number of personal reasons, but I believe there’s evidence in the text which suggests that the Tsuge story is more subtle and demanding in its imagery. There’s the accumulation of reasonably subtle detail, symbol, and metaphor over the course of the entire story, and these add to the complexity of the image of red flowers. The scene itself is conveyed with a lyrical quality which I find preferable to Tatsumi’s clumsiness. And while I did not touch on this factor in my article on “Red Flowers”, I wouldn’t say the equation of flowers with menstruation in that story tells the entire tale. One could look towards Leviticus (in the KJV) to see an earlier incarnation of this metaphor or even towards traditional botanical cures which suggest that the scene not only communicates pain but also healing.

Concerning Tatsumi’s failure “to move beyond what remains totally acceptable in modern day manga”, I am suggesting that Tatsumi was no better than many of the manga artists who work on a treadmill today in terms of his *stock use of figures and faces*. Now you could argue that this is acceptable because of what is traditional (and acceptable) in manga, but it would be an appeal to a pretty poor tradition as far as I am concerned. It compares poorly with Robert Crumb’s work in Genesis for example.

The comment on the demands of the “commercial treadmill” were in relation to his rushed art in some of the 1969 stories. I believe Tatsumi chose the stock figure of the male protagonist purposefully and included his comment in an interview with Adrian Tomine to highlight this point (see Note 2): “The character that looks identical throughout my work is, of course, different in each story, but he essentially represents my view. You could say I projected my anger about the discrimination and inequality rampant in our society through him. Do you see why my protagonists couldn’t possibly be handsome?” In the article above, I suggested a limitation in Tatsumi’s “creative abilities and imagination”, and a failure to break old habits were just as likely causes. Everything in those late 60s stories communicate this – a resort to the familiar.

Tatsumi also says the following in response to Tomine’s question with regards his “life and circumstances” at the time he drew the eight-page pieces at the front of “The Push Man” collection: “At the time I was a publisher of manga graphic novels for book lending shops. I would publish three to four books per month…We had six in-house artists and five to six freelancers. Of course I was publishing my own work too, but I was so busy running the business, I didn’t have much time to work on my own material. I had a hard enough time getting my checks cleared at the bank, so it was a hard life.”

Finally, I should add that this review isn’t an example of “venting” as far as I’m concerned. It’s a simple negative review of some of Tatsumi’s comics available in English. Apart from Bill Randall’s short review in The Comics Journal (linked to above), I don’t believe there have been very many forthright takes on the sheer mediocrity of Tatsumi’s manga in print and online (in the English language). Don’t you believe in a balance of opinion when it comes to criticism? Are you perhaps suggesting that the long list of notable comics critics who have praised his work are “straw men” (readers are welcome to do a Google search to see which individuals I mean)?

Thanks for the thoughtful response. Your follow-ups have been much more judicious than the original review.

Of course I believe in a balance of opinion when it comes to criticism. And I also understand the importance in voicing an opinion that contrasts to the norm. But clearly Tatsumi`s work is not without its merits, and the artist played a major role in the shape of postwar comics in Japan, so I feel like pissing on the work as lazy, inept, rushed, bad art is pretty gratuitous. Mass print paperback editions of this work existed in the 70s, so it`s not just “over investment in the worth of comics” or gaga-for-gekiga that has brought Tatsumi to where he is today. I also think Tatsumi is overrated, but I say that because of the astronomical heights his reputation has shot, not because I think he is mediocre artist. There should be a middle ground.

The difference in finish between Projectionist and Forked Road is obvious, and as you pointed out it probably has something to do with Tatsumi`s circumstances at the end of the 60s. (Side note: your quote about Tatsumi having a bunch of artists working for him…I think that means artists writing comics for the magazine-anthologies he was publishing, not assistants for his own work…but I will have to check this.) But first of all Projectionist-type crude drawing has a long tradition in kashihon comics in Japan (this is the point where is moving from kashihon to magazines), so I don`t think it can be chalked up to lack of time or skill, and the increase in finish over those two years also has to do with the different standards of the manga monthlies and weeklies, not just a personal aesthetic decision on Tatsumi`s part. That doesnt make the work better or worse, but I think one should, especially when critiquing an artist so harshly, have some consideration for context.

As for straw men, I meant the lines you quoted not the people. Those quotes might be representative of public opinion, but they are also sitting ducks. It`s just too easy to pick apart fluff.

I will reserve for another time full comments on Tsuge. I was just curious as to why you were so patient with his work, but not with Tatsumi`s. I think it has to do with more than complexity or quality. I too am a sucker for what you call Tsuge`s “lyricism,” as have been many Japanese writers over the decades. I think Tatsumi`s circa 1970 work is useful for laying bare what was swaddled in more palatable tropes in Tsuge.

As for film comparisons. How about Imamura Shohei?

Hi Ryan,

I think Tatsumi’s ’69 work is mediocre as is his “A Drifting Life”. As I’ve said above, some of the early 70s work is definitely above average.

I think it’s fair comment to suggest that the crude drawing should have been give better context (re: monthlies and weeklies) in the article above. In the same way, it’s understandable why “Black Blizzard” looks the way it does in the context of how he drew it.

Concerning the straw men and the lines I quoted, are you referring to the 2 blog quotes I used above and commented on? If so, I used them (in part) because most of the other English language writing on Tatsumi online amounted to short, somewhat grandiose comments in favor of his work. Those were the only decent analyses I found online. So if you’re implying (like Noah has in the past) that manga (comics?) criticism in America sucks in general, then I can only say that it is a reasonable opinion.

Tomine’s Tatsumi interview: From the way the sentence is structured, I’m pretty sure the artists Tatsumi cites were producing comics for his publishing ventures. Tatsumi seems to indicate that he was so busy supervising them and managing his publication venture that he didn’t have much time for anything else. If you find a better source explicating his situation, please let your readers here know if you have the time.

As for Tsuge and his resort to familiar tropes (and possible overratedness in view of this), if you would like to write an article outside your usual TCJ gig on this, I’m sure Noah would be *delighted* to give you a space on this website. I think that line of inquiry would be much better served (and highlighted) by a new blog entry than a comment on this old post. Are you reading this Noah?

I’ll have to view the relevant films by Imamura again to come to a proper opinion on his work (I presume you mean his 60s material; released as Pigs, Pimps, & Prostitutes by Criterion). He definitely has his supporters on this blog. What’s your opinion on them?

imamura compared to tatsumi?

i’ve only read the push man stories, i enjoy imamura’s films a lot more (especially profound desire of the gods, vengeance is mine, ei ja nai ka? and the eel.) many of his films definitely seem pretty polished, and even the crude bits (the jarring sequences with bad special effects, like the giantess in profound desire or the flying laundry in one of the early ones — can’t remember which) feel like they’re trying to inhabit some ironic space between lyricism and goofing off, which i don’t think was paralleled in any of tatsumi’s stories that i’ve read.

i can definitely see some similarities (without going into too much depth since i haven’t seen most of imamura’s pre-unagi films since the brooklyn retrospective in 2007, or read tatsumi since push man was published in english): particularly the brutally unappealing male protagonists and they’re amoral female counterparts. same general subject matter in general: murder, sex, and the working class.

some of the earlier ones like the ones in the criterion set suat mentioned feel like the closest match. i think by the mid-sixties he was getting more experimental starting with either the pornographers or a man vanishes (which is really pretty boring). after profound desire of the gods flopped i think the closest match might be his documentary about a sleezy bar owner/madame, the history of postwar japan as told by a bar hostess.

but in general i think theres a stronger lyrical strain (for lack of a better term) in his later films starting with profound desire of the gods.

Just quickly, on Imamura, I haven’t watched these in years, but the Pornographers maybe, Insect Woman, Ningen johatsu (probably not in English). They are much more humorous than Tatsumi, but there is some overlapping setting and gender views. The impact of Nikkatsu films is also big on all of the Gekiga artists, from the Action stuff to the romantic stuff. To me, Tatsumi belongs in that world.

As for Tatsumi’s busy schedule in the late 60s, when he started doing those dirty-men stories. His prose (versus manga) autobiography “Gekiga kurashi,” published last year, has a bit on this period. It says in short, the mid 60s were a difficult time. Then an editor from a second-tier magazine name Gekiga Young commissioned 2 x 8 pages a month from him, which he claims was hard work given his publishing venture. The editor apparently requested lots of revisions, less speech balloons, etc for a tighter more visual product. I would have to check, but these are probably the short works in Pushman. He also thanks the editor for getting him inspired about making manga again.

Later, he talks about how he had a long standing feeling against using assistants, arguing that one’s work should be one’s own. He says that in 1974 he had to swallow his pride and hire two assistants to complete a commission from Shukan Manga Sunday (a weekly). I will have to do more poking around, but the way things are worded here is that this was a turning point in the way he made comics. Maybe at the height of his popularity in the late 50s he had assistants, but given the economic difficulties of kashihon publishing in the mid 60s, I doubt he had them then.

This summer, I will probably write something on Tsuge’s Numa for TCJ, so I agree that that conversation is best saved for another time.

Yes I think most comics criticism is wanting, but so is most film, book, and art criticism. We all know that. I gave this some thought, and I think want bothered me about your piece is that, especially towards the end, your criticism of Tatsumi’s work is mixed up with your criticism of what has been said about Tatsumi. Probably that wasn’t your intention, but I felt that Tatsumi was being made to bear the responsibility for what’s been written about him. In the process, I think the differences you were trying to argue between 1969 and 1971 earlier in the piece was also being lost in a lump reaction to the reputation of the entire body of work.

For what it’s worth, I find Tatsumi very historically interesting, but only really exciting in small spots. After reading several volumes of his work, I began to wonder if the fuss wasn’t simply a result of D&Q and the larger alt-comics community trying too hard to rediscover a forgotten legend where no such greatness existed. That’s not to say that Tatsumi’s talentless – he was a pioneer, and his work certainly has its moments. It’s the sheer ham-fistedness of it that gets to me.

As others have pointed out, subtlety is not necessarily inherently good, nor brutal volume inherently bad. I’m a fan of the brutality of John Zorn’s Naked City and Maruo Suehiro, the size and mass of Sunn O))) and Richard Serra – but there’s a difference between being loud and being obvious. It’s obviousness that separates Gloomcookie from Edward Gorey, Cannibal Corpse from Naked City, run-of-the-mill drum machine goth bands like Nosferatu and London After Midnight from Siouxsie and the Banshees or Christian Death. Hackneyed tropes can be made good use of, and frequently are, but the way in which they’re used has to be interesting; I frequently felt in my reading of Tatsumi that he was not so much deploying obvious tropes for some good reason as simply being uninventive and obvious. I ended up enjoying his work more as historically interesting pulp than previously ignored literary gem – more pink film than Woman in the Dunes.

The trope of the pathetic man victimized by the seductive sexuality of wily women gets old mighty fast, too…

…not that I managed to say anything at all original in the above post – but I did want to add my voice to the fray…

Yeah, Tatsumi has never been shy about his influences (I believe film over literature). I don’t remember him mentioning any Nikkatsu film in particular but even a glance at something like Koreyoshi Kurahara’s “I Am Waiting” suggests some of the settings you find in his later work (not that these are particular to Nikkatsu I suppose): the dusky train stations, the light streaming through grilled windows, the primacy of the masculine viewpoint, the restlessness of the working class man, and the strange mix of East and West. The plotlines are mildly implausible and somewhat melodramatic. I prefer the more theatrical elements in classic American film noir.

Ryan: The final part of the article was firmly directed at American comics critics for their unrestrained promotion of Tatsumi’s comics (your mileage will vary of course). Tatsumi has nothing to do with that. In fact, he seems perfectly sane (?almost diffident) about the level of his achievement.

Anja: Part of it was undoubtedly what you say and the hype machine at work. There’s too little work from that period which has been translated to adequately gauge his achievements hence the resultant adulation. It should be noted again that Adrian Tomine is a huge supporter of Tatsumi’s work, and he’s been a significant force in its promotion.

This makes me want to watch more pinku eiga. I own and have read most of Behind the Pink Curtain, but I’ve only seen a tiny bit of pinku and roman porno. I’d also really like to get into girl gangster and women in prison films… There’s just so much interesting stuff out there that I’ve yet to digest.

I’d love to have Ryan write something here, yep.

And I didn’t say that manga criticism in English sucks in general! Sheesh; way to try to get me in trouble….

“Cannibal Corpse from Naked City”

NO NO NO NO NO! Naked City is great, but what separates the Boredoms from Cannibal Corpse has a lot more to do with form than with obviousness per se. Death metal is tight tight tight; Zorn is all about punk randomness. They’re both loud and confrontational, but the aesthetic is very different.

Sorry…you can all go back to discussing comics now….

Anja, if you’re interest in women in prison films you might want to read this.

Re: the comments comparing Nikkatsu to gekiga.

I haven’t watched very many genre films from the sixties, but I’m curious if there was much influence going the other way as well? gekiga –> film? The only clear example I can think of is Oshima Nagisa’s kamishibai-esque adaptation of Ninja Bugeicho. Are there any others?

Noah – I have read that, actually. :3

I actually think that Cannibal Corpse is trying to sound ultra-dense and megabrewtalle, and failing quite badly – hence the comparison. It’s the tightness that kills them, and that kills other death metal bands that attempt to sound super dense ‘n’ intense. Perhaps I should have made a closer comparison, though? Naked City vs. some uninspired, E.N.T.-derivative grindcore band?

IMO, death metal does best in aesthetic areas in which that tightness really allows an interesting and powerful composition to shine – Death’s album The Sound of Perseverance comes to mind. I can listen to Scavenger of Human Sorrows over and over and over…

Death is great; I agree that they are better than Cannibal Corpse. I still like Cannibal Corpse though.

Oh…and sorry for shamelessly promoting my same articles over and over again…

Heh – you are a shameless article-promoter, it’s true. :D I don’t mind, though.

Thanks for the interesting debate. I was once a Tatsumi fan, then wasn’t at all for a while, but with this conversation I think I have come to appreciate that body of work again, with its flaws.

“ave” asked about gekiga into film. There was TONS of this stuff in the 70s. I think you can get the Lone Wolf and Cub series in North America. The back history: there had been tie-ups between manga magazines, radio (when it was still current), and television at least back into the late 50s. Shonen Magazine and Sunday would not have progressed to where they did without many many TV tie-ins, some TV-first, some manga-first. Some titles were also turned into movies, like Shirato’s Watari (which was re-released recently on DVD, I saw it and it was great, even if it is for gradeschoolers). Come 1970 or so, it seems like pretty much every big Shonen Magazine title was turned into a film, especially if it was written by Kajiwara Ikki. Koike Kazuo followed suit in the 70s. I often walk past this old movie poster dealer in Tokyo, and almost every time see yet another one for some late 60s-70s manga made into a movie.

I think the question was asked at some point whether someone has previously wrote critically about Tatsumi. It’s not much, but there’s a little bit of that in my Garo catalogue last year, where I try to situate it as a general problem of “alternative” comics of that time. I’d write the section differently today, but for what it’s worth, it’s there. I am also mentioning this because I think Center for Book Arts and Picture Box are stuck with leftover copies…..which I imagine they would like to sell.

Hi Ryan, Many of the readers here are familiar with your catalogue and refer to it. I presume there will be a full length book at some point in time following your research. I think the main problem (re: sales) could be the price. They were selling it for $22 or something like that, and it’s quite a slim volume. Picture Box seems to have sold out though so there must be a demand for it.