A portion of the following essay was originally posted to this site, in modified form, as part of its Muck-Encrusted Mockery of a Roundtable, on April 15, 2010. Particular thanks go to Robert Stanley Martin for his valuable comments on that prior incarnation.

***

“If I have any real talent at all in comic writing, that talent is probably the talent for collaboration.”

– Alan Moore to George Khoury, The Extraordinary Works of Alan Moore

***

I blame this post on Jesus.

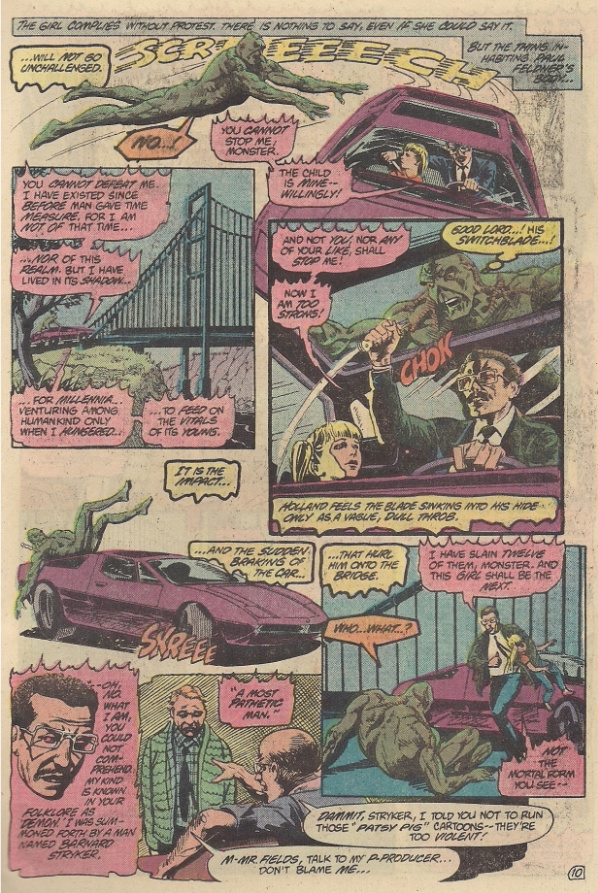

What you’re looking at here is the first picture that ever scared me. I was seven years old, in the second grade; class was taught by a wizened nun who kept the above image safely pressed under glass atop her desk, presumably for contemplative reasons, though it boasted the secondary virtue of creeping into eyesight whenever a child approached her desk. Maybe I was the only fraidy cat, I dunno, but – in the language of the Catechism, it fucked me up.

It was the first time I understood horror in art. I fixated on it, and eventually I found it beautiful: the contrast of colors, the displaced expression on Christ’s face, the implication that such suffering is the prelude to glory, yes, that the signal of violence needn’t mean just realist agony but anticipation of extra-mortal delight: the prospect of heaven causing the flesh to leap and part, insubstantial as residence of the transient soul.

I haven’t submitted any of that to academic review or psychiatric evaluation, but it was my furtive lil’ state of mind as I pretended to master my gerunds; moreover, it was the genesis of a fascination in horror fiction which, through a chain of events far too entertaining and sexy to detail here, prompted me to start writing about comic books on the internet.

This, however, only came after I met Jesus, aka James Caviezel, the commencement speaker at my college graduation, having just then completed principal photography on Mel Gibson’s The Passion of the Christ, which was based in part on the ecstatic play-by-play of a 19th century stigmatic nun, speaking of blood-spattered Brides of Christ and accordant stylized profundity.

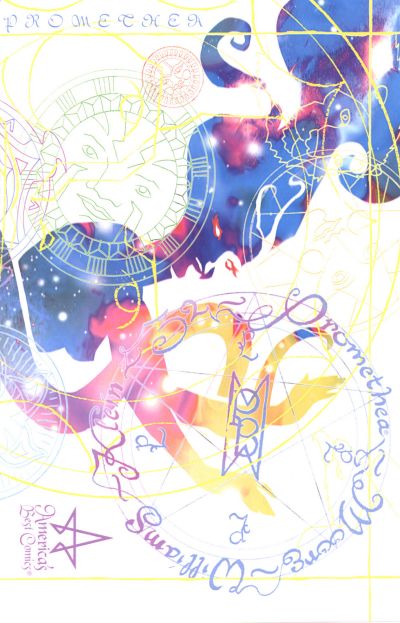

The most recent and interesting time Alan Moore ended the world came in October of 2004, on the occasion of issue #31 of the comic book series Promethea, which had by that time become the lynchpin of America’s Best Comics (“ABC”), an imprint of the comic book studio WildStorm Productions, owned by big scary comic book publisher DC since 1999, around the time the ABC line had begun. Moore, coming off the collapse of the Rob Liefeld-fronted Awesome Comics, with which he had enjoyed some success revamping the derivative superhero character Supreme into a friendly interrogation of the history of Superman, had signed on with WildStorm unaware that DC would quickly be in charge, or that the work-for-hire agreements he’d entered into would inevitably result in DC owning the characters. Nonetheless, purportedly out of concern for the artists he’d recruited to draw the ABC series — artists which would receive more money up front in work-for-hire circumstances — he continued.

As it went, the ABC line gradually became lashed together into a properly superheroic shared universe, in which characters from Series A might meet up with characters in Series B, and then refer to those events back in their own series, time having passed for the fictional superheroes as well as us, the readers. The exception, tellingly, was The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, the only one of the line’s books that was to be owned by the creators, Moore and artist Kevin O’Neill; all of the other series, it was eventually discovered, would fall afoul of the End of the World, in an amusing follow-through on the age-old superhero Event crossover promise that Nothing Will Be the Same following such and such a mighty crisis. With ABC, there would be a real and permanent follow-through on the enticement/threat, albeit as triggered not by an arch-villain but the title character of Promethea, who could access an immaterial plane of ideas through creative acts. A good portion of her series had already been taken up by a tour of said immaterial, a massive crossroads of fiction and ideas mapped into a Kabbalistic scheme. It was a vehicle for Magic.

I wondered at the time if Moore was acting this way as a means of ensuring that others couldn’t use these corporate-owned characters after him. But when issue #31 actually arrived, it became obvious that the End of the World was not meant as a cleansing act of mass violence, but as a shift in consciousness, in that ‘reality’ as experienced by humans is simply a product of their senses. As such, the World could End by reorganizing perception in a manner unstuck from time, so that the dead could appear along with the living and, presumably, people could ascertain other events in time.

Or, to put it in terms of timespace as a superstructure, with every moment in ‘time’ existing simultaneously in spatial relation to one another, Moore’s ABC citizenry could, potentially, stare backward at prior panels or forward at oncoming ones, like Harvey Kurtzman comedy characters living on a gigantic comic book page. They would understand their circumstances. It was humor! They would become realists, for comic book inhabitants, and thereby ascend to the same level as their creators, who so sweated and bled over those pages.

It was unclear how a story could continue like that, and so it did not.

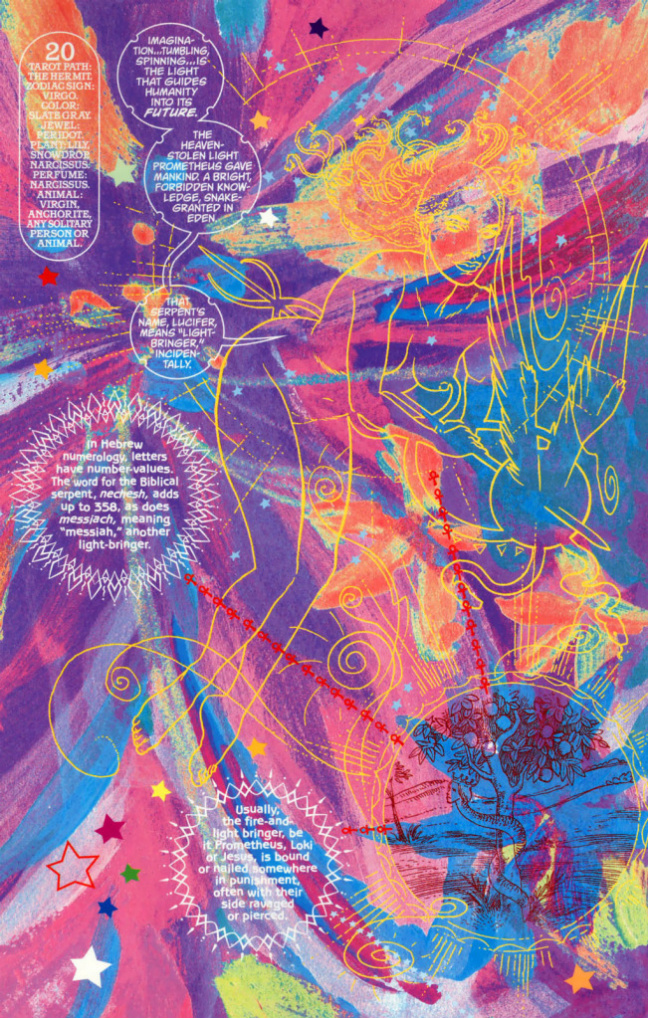

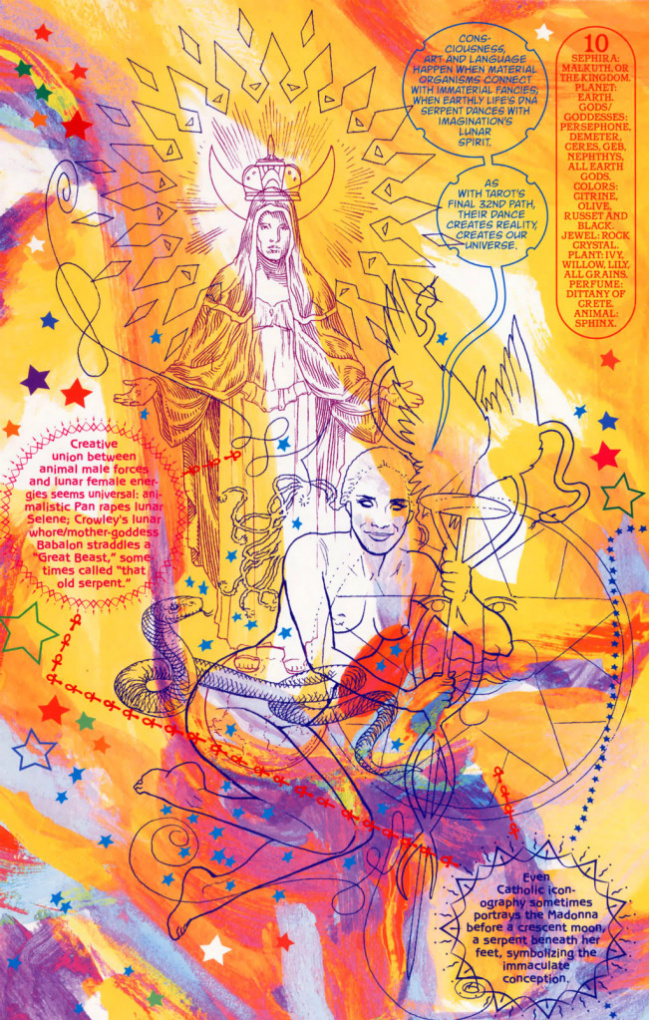

Promethea, however, had another episode to go; issue #32 was released in 2005, and can be taken as both a summary of the series’ themes and a wry continuation of its plot, in that Promethea, the creative superheroine herself, directly addresses the reader as to the nature of magic, all doors of perception having presumably been knocked open by the senses-shattering finale to the story proper.

It is hands-down one of the oddest comics DC has ever published, a crazed mass of searing colors and multiple narrative bubbles, made even more furious in its initial comic book-format release by the printer necessitating the reader to turn certain pages upside-down and navigate right-to-left – a fitting confusion indeed for the still-hot impact of manga in the mid-’00s (and ironically fixed for the collected edition). It was also a major, no doubt convoluted collaboration between writer Moore and designers J.H. Williams III & Todd Klein, their duties roughly divisible in terms of drawings/colors and typography; under the traditional superhero comic book division of labor, i.e. earlier in the series, Williams had served as penciller (gradually taking on other visual duties) with Klein as letterer, although the End of the World collapsed their contributions into a more intensive whole.

It’s a nice enough comic, mapping the many connection between the Tarot and religious traditions and etc. etc., although the great impact for me is in seeing how this shiny mass simulates Moore’s own conception of the Magical experience: it’s a map, allowing the reader to see the joining beams and critical architectural links of the universe. Moreover, you can elect to read it several different ways, following only the speaking title character’s specially-shaped dialogue balloons or reading them in conjunction with free-floating factoid bits. Or, if you prefer, you can literally take the comic apart — as in manually remove the staples from the item you bought — and rearrange the pages to form a double–sided story-poster, which can then be read again, in I’m told as sensibly a manner, by again sequentially following the dialogue.

There is an aspect of ritual to this: asking readers to physically destroy their comic book. Surely Alan Fucking Moore knows how many bags and boards there are in the world, how comics’ resale value as consumer items is based on physical condition. You might think comics are especially susceptible to the wear of reading and age because so much of their impact is visual, but nicks and tears and rips and superficial marks will do the trick of devaluing ‘work’ just fine without impeding the reading experience – to the extent that most comics are ever worth much of anything.

No, what Promethea asked, as the coda to the final event in Moore’s final extended superhero effort in a career that, like it or not, remains acknowledged mainly for its effect on the superhero genre, that you put any taboo concern for destroying a comic aside and obliterate it to make it new, and from that glimpse a little more of the Moore/Williams/Klein simulacrum of being. Grant Morrison can revive every one of these characters in Batman, Inc. next month, if he and his editorial consorts so choose, but Moore, looming above, declares that this act of Magic is complete, and begs your humor of its individuality.

***

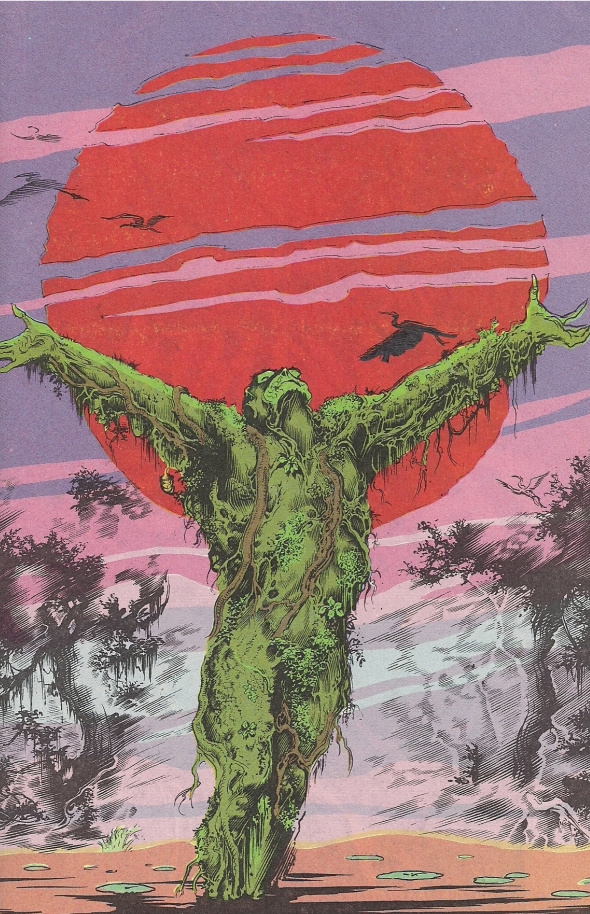

An earlier example of obliteration came in the shambling, leafy form of Swamp Thing, who met Jesus once; it’s just something me and him have in common.

Both of our encounters were unreal. Mine because I, in my cap and gown, was actually being asked to sing happy birthday to the Pope with the rest of my graduating class by the leading man of the 2001 Jennifer Lopez vehicle Angel Eyes — while queuing to march to our seats a fraternity brother asked Caviezel what it was like to sleep with J.Lo and got a look like he’d just dipped his balls in the holy water — whereas Swampy’s was never published, which meant it was not in continuity, which in a superhero universe means it wasn’t real. Rick Veitch, who’d co-pencilled the character’s exit from the tomb in The Anatomy Lesson, Moore’s second issue, had become series writer by that time, because shared-universe characters are generally expected to go on sharing for the good of their readers and, in the case of DC, their multinational corporate masters; he’d planned to cap off an extended time-travel storyline with a quick stopover at the Crucifixion.

It was 1989 then, and it had been said the prior year’s ferocious controversy surrounding another sorrowful motion picture mystery, The Last Temptation of Christ, put the fear of god into publisher DC. The story was squelched and Veitch resigned his position, as did both of his scheduled alternating successor scribes, Jamie Delano & Neil Gaiman, both of whom had started working in North American comics on Swamp Thing-related projects, bearing the massive influence of Alan Moore.

Gaiman wasn’t even one published year into The Sandman at that point; Moore’s issues of Swamp Thing had brought him into reading comics as an adult, or so he relates in the supplementary materials for the 1999 superstar miscellany collection Neil Gaiman’s Midnight Days, noting that his first attempt at a comics script was effectively John Constantine fan-fiction, albeit read and commented upon by Constantine co-creator Moore himself, shortly after the character’s introduction in the pages of Swamp Thing. His second script concerned a 17th century version Swamp Thing; it too was sent to Moore, but also Swamp Thing editor Karen Berger, who took the work under consideration and eventually, in 1987, met with Gaiman and artist Dave McKean to start to devise what became the plant-based miniseries Black Orchid.

By that time, Constantine’s other co-creators, the guys that took his image from Sting and demanded his character from Moore, Stephen R. Bissette & John Totleben, had already left Swamp Thing, at least as the primary penciller and inker they’d respectively served as since before Moore had started. Both would return a few times, the last one being in Midnight Days itself, reuniting with colorist Tatjana Wood and letterer John Costanza to realize that old 17th century manuscript, which may not have existed if it hadn’t been for Alan Moore.

This is the last page. I’ve cropped out the credit box, which I didn’t read very closely the first time I went through the book in 2002. Everyone knows Neil Gaiman, everyone knows Alan Moore. Even in 1993, in junior high, when I was reading mostly Marvel and Image comics, I knew Alan Moore was important. Swamp Thing was important. Er, mostly I’d heard Watchmen was important, to be honest, and I’d never managed to read it because Dave Gibbons’ art looked so old and boring. And how the fuck am I supposed to choke down a comic with crappy art when I could be re-reading Shadowhawk?

Adjacent to the cropped credit box:

I had no idea who that was, or what the hell he could mean.

***

I was born in 1981, exactly 14 days prior to the premiere of Deadly Blessing, a now-obscure Wes Craven film concerning possibly supernatural murders out in the sticks; I’ve never seen it, but the “eastern Pennsylvania” mentioned in the trailer is maybe an hour’s drive out from where I sit right now. Doubling down on remote locales and connections to my everyday life, Craven’s next project would be some damn thing about a swamp monster, which would boast the not inconsiderable virtue of reviving interest in the comic book incarnation of such.

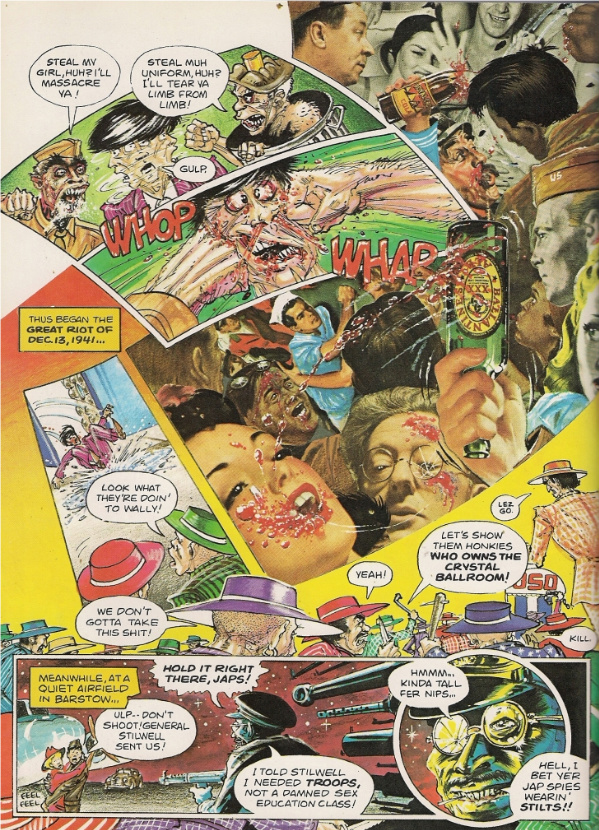

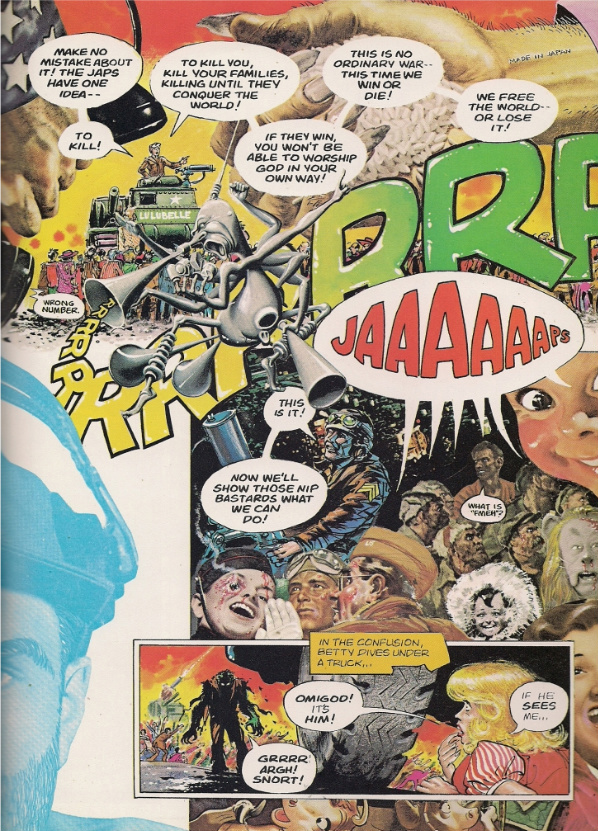

By that time, Bissette and Veitch, of the recent, virgin graduating class of the Joe Kubert School of Cartoon and Graphic Art, were already cover-credited veterans of the motion picture industry as related to comics, via 1941: The Illustrated Story, a splendidly spastic Allan Asherman-written Heavy Metal presentation of 1979, no doubt saddled with high hopes given the smash success of the magazine’s last sponsored movie adaptation, Archie Goodwin’s & Walter Simonson’s Alien: The Illustrated Story.

Two of the duo’s former classmates at the Kubert School, Totleben & one Thomas Yeates, provided assistance, while Irwin Hasen, co-creator of Dondi, illustrated a special introduction depicting filmmaker Stephen Spielberg surrounded by scantly-clad women and showered with money whilst declaring, in his own words, that over half the film’s budget had been spent on prostitutes and drugs, and never at any point indicating that you, reader, were about to experience a comic or an Illustrated Story or a whatever-the-fuck, although the original motion picture screenplay “appeared to have been written by two guys whose only excursions into literature had been classic comics.” Heh.

Following the book’s release — an unsuccessful one, even compared to the famous ‘failure’ of the movie (which actually made money) — Spielberg informed Heavy Metal (in a letter reprinted in Bissette’s SpiderBaby Comix #1, 1996), that he had been “mislead” by the b&w proofs provided to him, that the completed art “does not represent the intentions of myself, the writers or anyone connected with 1941,” and that it all really was “a savage representation of an otherwise light comedy about those times,” in addition to being “off-putting, disgusting and terribly racist.” He did, however, praise Bissette & Veitch as “ruthlessly talented (though demented)” and jokingly noted their recommendation to Francis Ford Coppola for an adaptation of Apocalypse Now, which, as the film buffs among you might know, had initially been scripted by John Milius in the late ’60s as its own brand of comedic assault, informed by pop militarism along the lines of Sgt. Rock, co-created by Joe Kubert, issue #311 of which had, in 1977, featured Bissette’s & Veitch’s first-ever work for DC Comics.

But to the acclimated among what few readers the 1941 comic had, it must have been obvious that Bissette & Veitch (the latter of whom apparently took over the scripting too as time grew tight) possessed an understanding of the classics that went deeper than a lineage of corporate-owned shootings; behaving like Kurtzman & Elder as filtered through a decade’s worth of the underground funnies they’d inspired — though more than a few of the underground talents in fact worshiped in the horror wing of the EC pantheon, among them Veitch’s brother Tom — the artists staggered bloody and determined through wet fields of cut-out, pasted-down period catalog faces and ironic, troubling ethnic caricatures to deliver an acidic point of view that might be clarified by an older Bissette’s 1996 interview with Kim Thompson for The Comics Journal (#185), commenting on high-profile opponents of violent and horrific movies:

And, see, this to me is the hypocrisy of of our culture: that Star Wars is revered [laughs], and Blow Out would be something that would be deigned “reprehensible.” It sounds like I’m out of left field here, but hear me out, Kim. Star Wars is the film that put our culture, here in America, back on the path of being able to entertain the notion of participating in a war again. Prior to Star Wars, even American cinema had gotten to the point where it was not possible to make a pro-war movie…. Star Wars turned it around, because it found a vehicle, through science fiction imagery, and the non-reality of setting it an a galaxy far, far away, of once again allowing an audience to revel in the romanticism of war.

And 1941 certainly reveled — perhaps as vigorously as Milius’ Apocalypse Now, had it been directed by an early interested party, George Lucas — but mainly in ludicrous vulgarity attributed to the Greatest Generation, portrayed as a seething lot prompted to combat not out of any particular yen for duty but a volcanic combination of lust, paranoia and, most of all, overwhelming, all-consuming racism. The visual display was a fantastic mess of human ugliness, borrowed horror comic tropes and funnybook excerpts, marshaled for the purposes of stripping the gloss off idealized combat, of ‘good’ warfare – not an easily glimpsed tactic under today’s Spielbergian gauze.

It was a mean, sneering, SNORT!ing comic, and a politically aggressive one, but also presented as a big movie studio’s tie-in item for a would-be blockbuster, which was not generally the makeup of underground comix-note-the-x as found in the head shops. That’s why publishers and marketers apart from the superhero mainstream were deeming their wares “ground level” comics by ’79, denoting some obvious visibility and accessibility — by way of the growing Direct Market of comics-focused retailers — without foreclosing on the idea of digging up from the underground, like a hungry live corpse wobbling in plain sight… which could also serve as a less flattering metaphor for the ‘mainstream’ comics of the day.

***

In 1978, DC had seen their ranks cut down by over 30 titles. Among the casualties of this capitalist implosion was a planned revival of the Len Wein/Berni[e] Wrightson property Swamp Thing. If you’ll indulge me some shithead poetics, I’d like to posit that leafy lump of green as a carrier of North American comics’ mark of Cain, or possibly Abel.

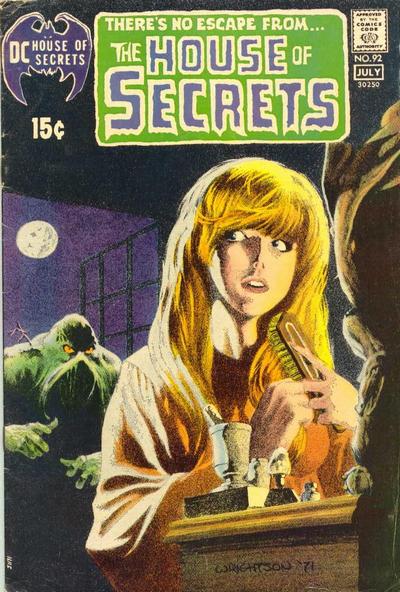

You see, the character Swamp Thing debuted in 1971, in issue #92 of The House of Secrets, a throwback spooky anthology title with an old fashioned horror host, the biblical Abel himself. Naturally, where there’s an Abel there must be a Cain, who served as host of a much longer-lived comic, [The] House of Mystery, which, fitting for its crueler master of ceremonies, actually was an old-timey horror title, est. 1951. The EC comics eventually beloved of the underground were becoming leaders of the American art by then — The Crypt of Terror (later Tales from the Crypt) had debuted in late 1950, inhabiting the form of a no-longer-so-trendy crime comic, Crime Patrol, and the likes of House of Mystery no doubt followed in the wake of this New Trend — and as simplistic and frankly difficult to read as they are today, the best of them, the ugly and ironic SuspenStories, the Kurtzman war comics and the against-the-status-quo assault of Mad, predicted a possibly boisterous post-adolescence, perhaps in the way manga swiftly grew up in Japan around the same time. But then came the Comics Code Authority in ’54, which squelched any nascent maturation as related to comic books as a format.

That would have to wait a decade for the arrival of the undergrounds, creator-owned and uninhibited; they didn’t exactly die out as the ’70s began, but the collapse of viable distribution outlets limited their reach, at least until the Direct Market began to grow. By that time, their own influence could be felt on younger talents dispersed across a funnybook landscape troubled enough that student artists might observe an instructor in tears because her spouse had just been fired from DC, as Bissette related in a 2009 interview with the AV Club. “I wanted to reinvent horror comics,” he said of his goals back then.

As it happened, Len Wein, by then an editor at DC, managed to sell the idea of a revived Swamp Thing to accompany the Craven film; the initial writer was superhero veteran Martin Pasko, and the first artist was Tom Yeates, of the small aforementioned notation in 1941.

By then it was 1982, the year Fantagraphics began publishing Love and Rockets. Occasionally, folks peg that as the beginning of North American “alternative” comics, the definition of which vacillates between qualitative concerns and notions of audience and distribution; some are just as likely to name RAW in 1980, or Cerebus in 1977, or American Splendor in 1976. History is a slippery set of narratives, even just talking about Swamp Thing. If only someone could put everything in its place, sort out the past, isolate the odder growths and degeneration, and lay out the mossy entrails to read the future. An autopsy would do the trick.

***

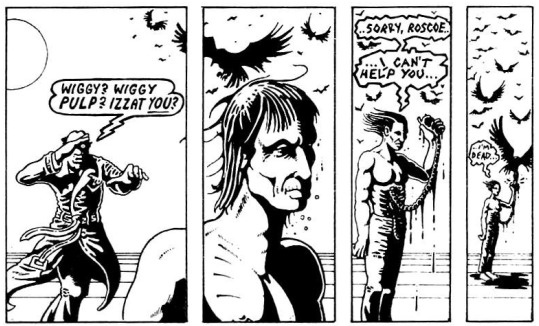

Meanwhile, across the Atlantic, an underground-minded artist of similar and purportedly anxious Kurtzmanian influence had recently elected to pare down his drawing output — including four years of total work for the music magazine Sounds (see above) — to weekly dispatches from the Schulzian world of Maxwell the Magic Cat, the better by which to prolifically script.

For as long as I have been alive, Alan Moore has been writing comics, but even by 1983 his focus had shifted significantly from his satirical, loose-limbed work as a writer/artist to inquisitive adventure works fit for serialization in sympathetic forums, as drawn by collaborators with genre chops. He’d already begun V for Vendetta and the revival of Marvelman and his run on Captain Britain, among other works. Then he got the call from Wein to write for American comics – indeed, shared-universe superhero comics, albeit a tangentially related and low-selling example of such.

This is typically where the Alan Moore Story kicks into high gear, since it’s where his influence on comics becomes evident. Much focus is lavished on issue #21 of The Saga of the Swamp Thing — and what a portentous title, in every conceivable way! — which was neither Moore’s first issue of the title nor the debut of artists Bissette & Totleben, though it was the place where all of these not dissimilar, progressive-minded, underground-informed, genre-tilting folks met, with the added resonance of letterer John Costanza, a former Joe Kubert assistant, and colorist Tatjana Wood, the only one among them to have actually worked (uncredited) on some old EC books, as well as below-the-radar works by her once-husband, the great Wally Wood.

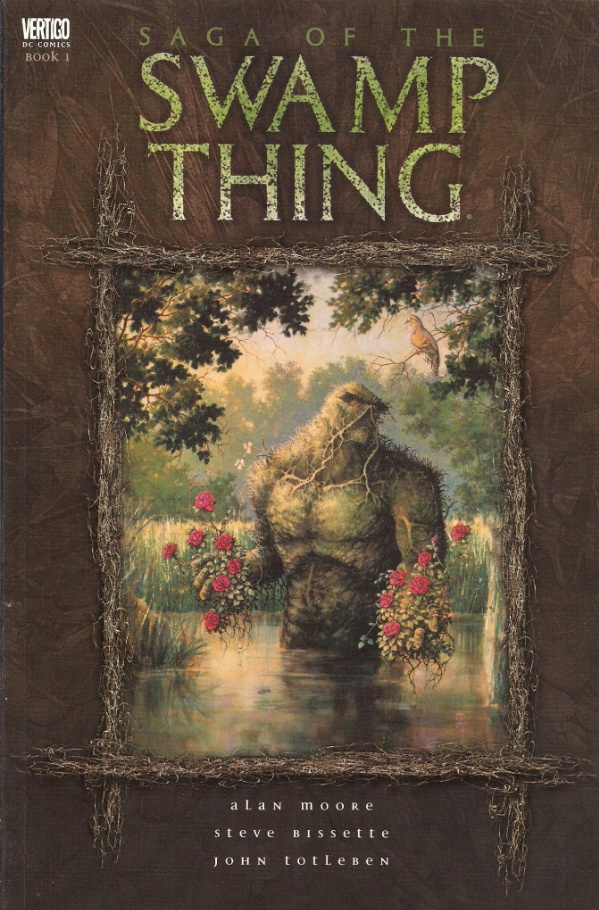

That issue was The Anatomy Lesson, the place where Moore set out his massive rethink of Swamp Thing’s character – it made for a natural kickoff for the old Vertigo softcovers, Vertigo being the Suggested for Mature Readers line Moore basically inspired by his example. That’s where I first read the stuff; I heard it was quintessential Alan Moore. Who drew this stuff again?

This is the only one I still have, the first of six tomes collecting Moore’s tenure as writer, its front cover plastered with a fine Michael Zulli painting that has absolutely fuck-all to do with the visual aesthetic of the interior pages; its back is covered by Moore’s own famous ad copy insisting “You shouldn’t have come here.” Then, as soon as you’re past the table of contents, there’s Ramsey Campbell’s foreword, quoting Moore’s opening narration to The Anatomy Lesson. After that comes a lengthy introduction by Moore himself, who expounds upon the quirks of ‘horror’ writing in a shared-universe superhero comic, as well as its potential:

Imagine for a moment a universe jeweled with alien races ranging from the transcendentally divine to the loathsomely Lovecraftian. Imagine a cosmos where the ancient gods still exist somewhere and where whole dimensions are populated by anthropomorphic funny animals. Where Heaven and Hell are demonstrably real and even accessible, and where angels and demons alike seem to walk the earth with impunity. Imagine a planet where exposure to dangerous radiation granted the gift of super-speed rather than bone cancer, and where the skies were thus filled by flying men and women threatening to blot out the sun. Imagine a place where people were terribly good or terribly bad, with little room for the mediocre in between. No, it certainly wouldn’t look very much like the world we live in, but that doesn’t mean it couldn’t be every bit as glorious, touching, sad or scary. With this kind of perspective, the appearance in these pages of the Justice League of America or vintage DC super-villain Jason Woodrue should be less unnerving than it might otherwise have been to the uninitiated.

The optimism here is startling, and indicative of a certain disconnect between members of the creative team: if Bissette was interested in backing horror into wherever it would fit, Moore sought to blend it with its surroundings. After his mission statement, Moore moves on to a synopsis of the series prior to The Anatomy Lesson, oddly without any indication that he’d written an issue’s worth of it; a seamless result seems to be the intent, as unified as the writer’s vision of a whole DC Universe. “And as we watched Alan’s career skyrocket,” said Bissette, to the AV Club, of problems that later arose, “you know, we were still the lowly Swamp Thing cartoonists. So that was a schism.”

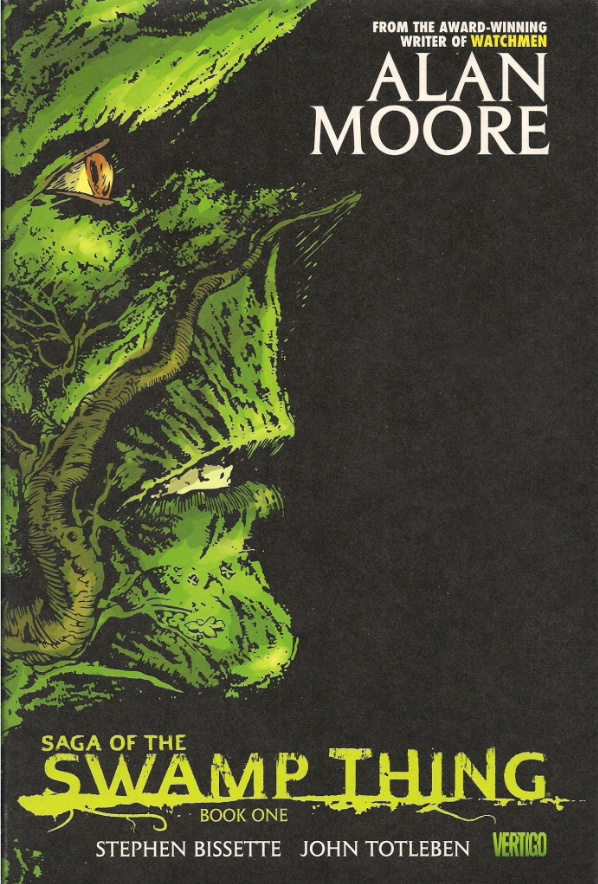

Since the vessel that is Alan Moore’s career at DC still collects considerable amounts of money, reissues are inevitable. This is the first of four currently-released Swamp Thing hardcovers; it seems matched up with vol. 1 of the old softcovers on first glance, and surely appears to be Moore-centered to an even greater degree than before. Yet once you look closer, fascinatingly, there’s actually less. The front cover art is Bissette & Totleben. The back cover is missing Moore’s long narration. Inside, Moore’s introduction is now totally absent, and preceding Campbell’s rather writing-centric foreword is a new introduction by Wein, who serves up some meat ‘n potatoes as to the series’ development, like how Bissette & Totleben assisted original artist Yeates, eventually succeeding him as artists.

Specifically, they began on issue #16, four issues prior to Moore’s arrival. It’s important to realize that they weren’t just looking for craft assignments in particular roles, a ‘penciller’ for drawing and an ‘inker’ for embellishing; it was actually Totleben who devised the ultra-tactile look of the ‘updated’ Swamp Thing character design that would eventually appear during Moore’s tenure as writer, though editorial preferred him as an inker over Bissette’s pencils. Bissette & Totleben — typically credited on-page as “artists” rather than acknowledging a specific division of labor — also wanted to contribute story ideas, and Rick Veitch soon began contributing supplementary pencils, initially without attribution. And if you compare the tables of contents of my old softcover edition and the new hardcover, the former will only give you pertinent co-plotting and co-pencil attribution in an acknowledgments section down bottom, while the latter places them within the chapter information going down the page.

All of this seems keyed to replace seamlessness with completism; there’s even cover reproductions breaking up the placement of each issue. But Moore’s old intro seems to have nonetheless been deleted as a redundancy, because issue #20 is finally included, Bissette sitting it out — by which I mean pencilling an already behind-schedule issue #19 via a beleaguered, departing Pasko dictating page content by telephone, and then putting together issue #21 with then-uncredited aid from Veitch — while Totleben inks fill-in penciller Dan Day, working under serious time constraints.

***

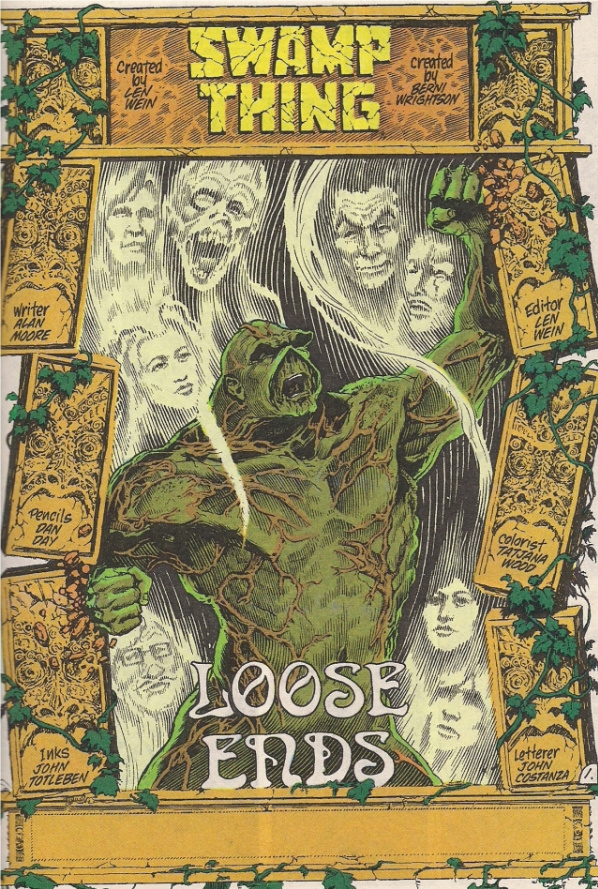

Eh, subtlety isn’t always necessary. This is the first page of the bold new era, and while it may not involve plump, warm summer rain that covers the sidewalk with leopard spots, or Blood? I like to imagine so. Yes, I rather think there will be blood. Lots of blood. Blood in extraordinary quantities, I will note that it also does not have an anatomically inclined chapter title housed in the broken outline of a body. This one’s almost pure image, with ghostly swirling supporting cast members taunting Our Man as he freaks out in classic monster movie style while alluding to the biblical Samson, de-powered and enslaved, making a sudden comeback to destroy the Philistines along with himself.

The simplest metaphorical reading suggests that someone maybe wasn’t 100% delighted with Martin Pasko’s concepts, but look closer – if the supporting cast are ghosts, Swamp Thing isn’t going to crush anything but himself, presumably with the names of his original creators. Also, what does Loose Ends have to do with toppling a pair of pillars? Realize that Swamp Thing isn’t tying anything up; he’s knocking the ends of the page loose, upsetting the symmetry that cages him. He’ll die, but it’ll free him – this is not an idle joke or a petty irony, it’s a statement of purpose, and the start of a visual motif that will run throughout the issue, to varying effect.

That sounds very writerly, very Alan Moore, yet further study suggests the type of collaboration that would come to define the early issues of [The Saga of the] Swamp Thing and leave them still memorable today – something equal parts inspired and improvisatory, and somewhat at odds.

In 2009, Bissette posted a wealth of production materials relating to issue #20 onto his website, including Dan Day’s original pencils for the very first column-smashing image. From even a cursory glance, it’s obvious that inker Totleben engaged in a not inconsiderable amount of wholesale revision of Day’s pages, adding in the ‘ghosts’ of the supporting cast and swapping out a lumpen, Toxic Avenger-looking ‘human’ Swamp Thing with a hulking mass of vegetation in keeping with his own ideas for the character’s look, which would find much purchase as Moore’s tenure continued.

Of course, Totleben had inked several issues of the series before (in addition to his uncredited contributions on various Yeates issues), but Bissette has speculated that Day might not have had time to see any of the Bissette/Totleben content, scheduling being what it is in comics, and based his own rendition off of Wes Craven movie-related materials. Likewise, examination of Moore’s script reveals that this toppling debut splash was not Moore’s intended image, although he did include several (to Bissette’s mind unprecedented) provisos that the artists, colorist Wood and letterer Workman included, were free to add their own input onto the page if so inclined, with Moore’s panel descriptions to serve as pacing guides for the storytelling. This in spite of the fact that Moore was not aware at the time of script’s writing as to who, exactly, would even be drawing the issue. Ah, comic book culture!

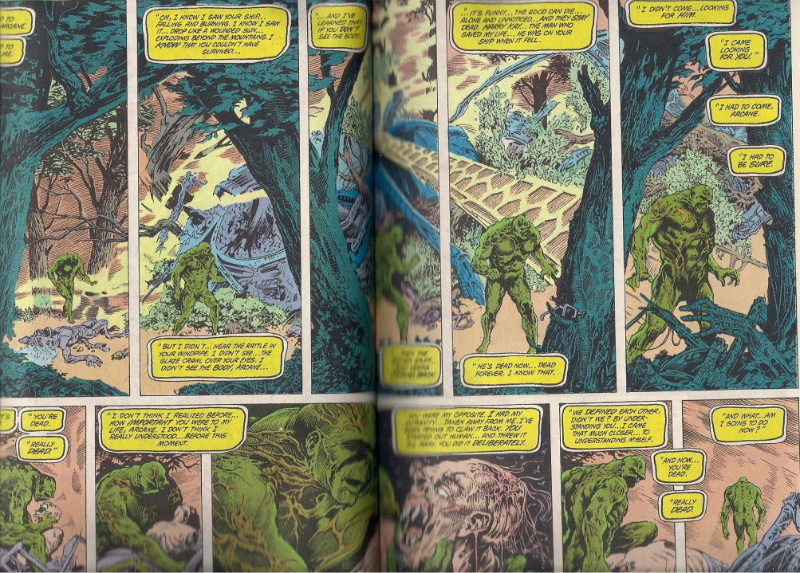

This is what you see next. Excuse the crummy scan, but I think the idea comes across – it’s a symmetrical panel layout, variations of which will appear on all but the last three pages of the issue. Swamp Thing is pontificating at length on the apparent death of arch-fiend Anton Arcane — as Moore mused in a letter to editor Wein at the top of his script, “I suppose my main dissatisfaction comes from [issue #20] having a little more plot than I’d have liked and a lot more copy, despite my intentions to keep the actual verbiage down to a dull roar” — with the bisected center bottom panel helpfully presenting his head on one side and Arcane’s on the other.

I suspect the first thing that will come to mind is the symmetrical issue of Watchmen (#5): Fearful Symmetry. However, going from Moore’s script, Bissette notes that the double-wide layout was, in fact, Day’s invention, apparently as a means of compressing three script pages of information into two, following his own invented opening splash. Departures of this type had a curious effect on the issue, in that Len Wein had gotten so enthusiastic over Moore’s early scripts that Day’s infidelity, understandably time-crunched as it might have been, prompted the editor to encourage Totleben to revise the pencils in inked form. In other words, the finished issue was both unlike Moore’s script yet more in keeping with the series’ established visual style than it likely would have been under a straightforward guest pencilling job, in that the series’ constant inker was impressing a more-than-average amount of his personality onto it.

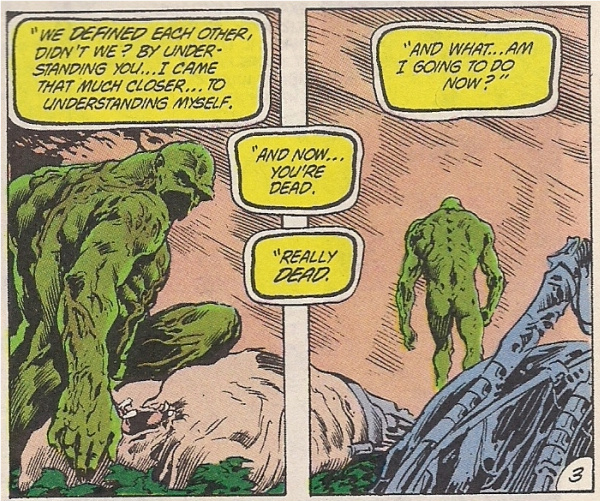

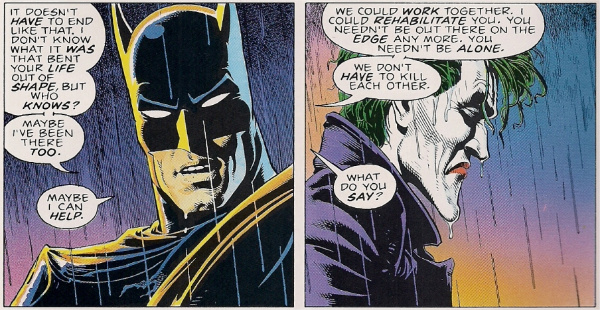

And yet, Moore remains. You can’t make it out above, so here’s the final two panels from this spread:

From this, we can anticipate another, in-continuity descendant.

The Killing Joke is not a symmetrical comic, but it begins with an extreme close-up of rain striking pavement, pulling back onto the top tier of a nine-panel grid as headlights cut across the splashing surface of the water. At the end of the book, with Batman and the Joker merrily laughing at how insane they both are, the bottom tier of a final nine-panel grid zooms into splashing rain, headlights killed, then an identical extreme close-up on the last page. It captures the duo, silently assuring us that they can’t change, that these stories will probably continue forever.

Moore has often expressed dissatisfaction over the work, insisting that it’s just a story about Batman and the Joker and unfortunately nothing deeper, but I wonder if he’s really upset with the futility inherent to his structural conceit. Symmetry, in Moore’s work, tends to denote a cosmic or infernal loop; the accidental symmetry of Swamp Thing operates in much the same way, but as prelude; anticipation of revisions to the character and his world.

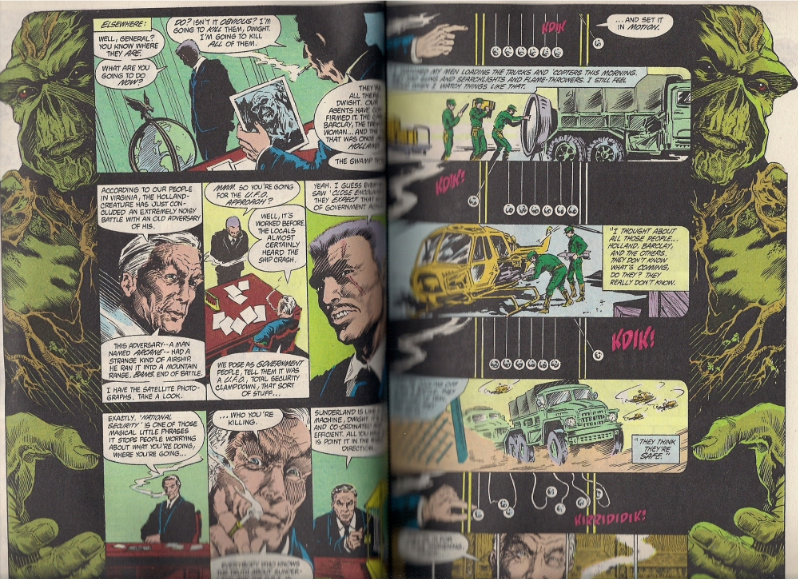

Here are some villains, their decidedly non-symmetrical conversation nonetheless dominated on both ends by its topic; a faux-symmetry. Without further script pages to examine, we might wonder if the layout here is a means of harried penciller Day attempting to get all of his narrative ducks in a row, imposing some visual ‘organization’ on Moore’s 43-page script. Yet, this conflicted effort is oddly rational; a scene with no good guys needn’t convey a sense of entrapment, just preoccupation, and anyway the bit with the clicking balls — itself a representation of perfect action and reaction, upset at the end — will recur when the whole thing breaks down later. That last part at least was Moore’s idea, as shown by Bissette’s posting of the final two pages of Moore’s script.

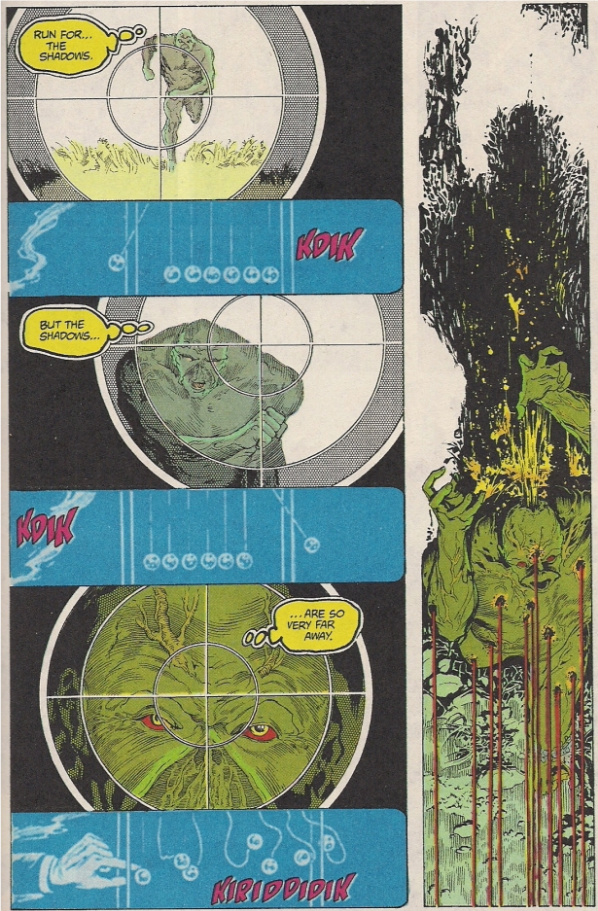

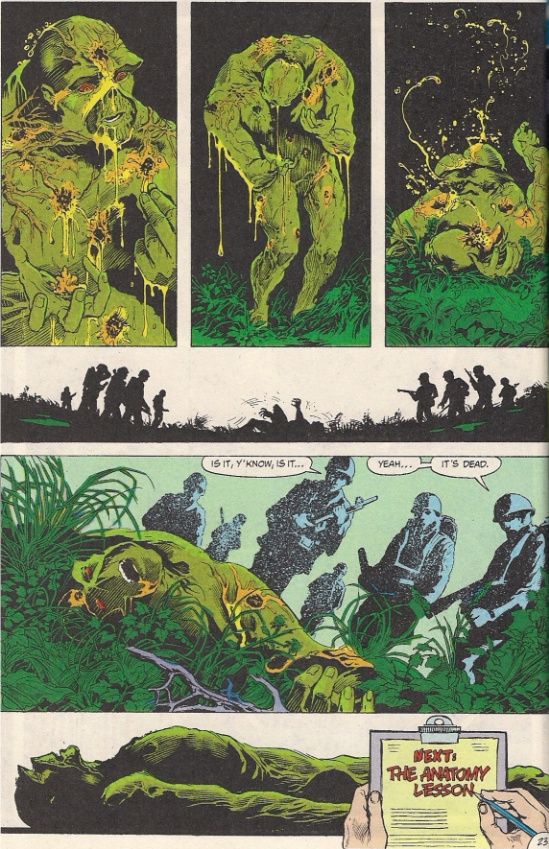

And here’s the printed next-to-last page; Bissette notes that at this point Totleben was completely redrawing Day’s images. Fittingly, the (faux-)symmetry breaks down as Swamp Thing is shot, with a prominent member of the series’ primary art team taking over from the guest penciller, driving him right out of the book, and in the process maybe exercising more authority than he’d enjoyed before. The death of a character, and a way of making corporate comics, labor divided and communication at a minimum. A revolution by mishap.

Literarily, though, it does all form an interesting and subtle type of branding. Swamp Thing muses at length on how forms of light are driving away the shadows, the places to hide – he’s talking about modernity, casting back the weird mysteries and their small conflicts. “Aren’t they… going to leave any darkness… for us, Arcane?” From his surroundings, we can tell that Swamp Thing cannot escape this incursion. From the first page, we know that he will have to die to escape the confinement. This is a modern comic, says Moore, says Day & Totleben, this is the last stand of the old hero-villain dichotomies, which cannot stand up to the light of scrutiny. It’s 1983, and as the bullets that are blasting open the title character’s head point to, the shadows, the mysteries come from within, not outside.

Look at the thought balloons. This is the last you’ll see of them for a while; their proliferation is partially a flaunting of old-school comics techniques, which will be traded in for ‘sophisticated’ captions starting next issue. Not that Moore hates them or wants them to vanish forever – they’ll reappear in Annual #2, when Swamp Thing visits the land of the dead, and then in issue #33, when devoted love interest Abby Arcane witnesses the occurrence of the Swamp Thing character’s 1971 first appearance. They’ll have their place. Everything, everything will be put in its place.

All part of the corpus, all fit for dissection. You don’t need me to tell you how The Anatomy Lesson acts as its own freestanding metaphor for revamping a comic book character, picking it apart and seeing how it stopped working, and how it might miraculously work again. It’s referential to what’s primarily a writer’s task, and it’s Moore’s writing that has always dominated the discussion of this series. It needn’t, though in some ways it must.

Aaaand since I didn’t make it explicit in the body of the post itself, note that this is part one of two.

Pingback: Best Action Figures of 2009 - Linkarama@Newsarama

This is a really compelling essay- you’ve actually made me want to read Swamp Thing (you can use your own judgment as to whether or not this is a good thing). As to that image of Jesus- good lord! That really is a horrific and strangely attractive painting. Those background colors…

You’ve never read those old Swamp Things, Sean? They’re really pretty great. I mean, uneven, but many many enjoyable bits, and the art is consistently good….

Well, as an adult I’ve managed to avoid entering into any new corporate-owned, endlessly spooling serial narratives, and so unless one was grandfathered in by my interest in earlier years, I’m unlucky to have the exposure. It’s just really hard for me to go in knowing that, no matter what, the status quo won’t be overturned- no one will die, nothing will change, nothing will never have any consequences. But it seems like these issues will be worth making an exception. Glancing at my shelf now, I see I’ve also made exceptions for Ditko Spiderman, some Wonder Woman (thanks to you, Noah, and a library sale), some 50s era Superman reprints, some scattered Kirby comics, none of which I have any childhood associations with, all of which go on forever without any danger, and yet I’ve somehow brought myself to read them anyway… insert non-yellow emoticon here.

(the thing about excepting things associated with my childhood is really problematic for me- it’s also the explanation for why I have volumes of “X-Men Essentials” and boxes of New Mutants and GI Joe comics at my house!)

Oh, other notable exception- a volume of 70’s era Ghost Rider reprints. Cause, you know- the guy rides a motorcycle, and has a flaming skull for a head. It’s also very charming (and simultaneously alarming) to read a comic in which Satanic rituals are enacted and invoked constantly, but which can’t mention the name “Satan.” Delightful! If only my childhood had some Ghost Rider in it…

The Swamp Thing run as a whole is fairly self-contained; beginning, middle, end. It wander somewhat, but there’s definitely character progression and people dying and those things mattering.

The key is just to stop when Moore does. The character drones on, but you don’t have to….

yeah, as a teenager “Swamp Thing” was just something I just went back to over and over. Right when you needed something “meatier” to read. It was either that or nothing as far as the mainstream went. Rick Veitch’s run on it might not have been too bad, actually. My sub ended a few months into his run. I remember liking the scene where one character (Constantine?) is in Arkham, asking why the Joker is laughing at a book. Look closer, and you see he’s reading Kant’s “Critique of Pure Reason.” That was a nice touch.

I always suspected The Joker was a die-hard Spinozist at heart.