by James Romberger

François Truffaut’s films are most often analyzed in terms of their cinematic structure and the interpersonal relationships of their stories, and these qualities do account for a good part of their appeal. His films are not considered particularly political in the context of his contemporaries of the French New Wave. However, Truffaut does critique the forces that shaped his world: the destructive nationalism and militarism that crush people and culture in their wake, and the patriarchal structures that keep women the longest-suffering victims of oppression on the planet. Since women do not share equal rights with men, gender relations are political. Truffaut made some sincere efforts to explore those dynamics.

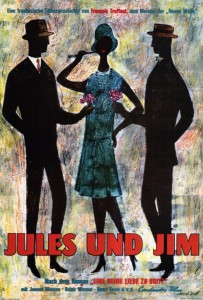

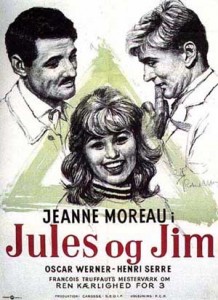

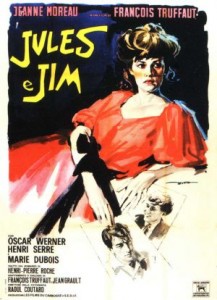

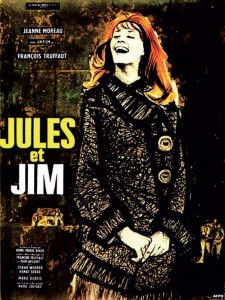

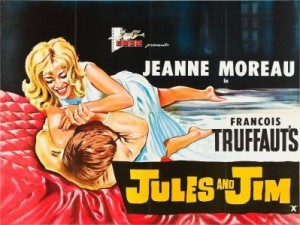

Truffaut’s 1962 film Jules and Jim bears reexamination in this light. In his adaptation of Henri-Pierre Roché’s semi-autobiographical novel Jules et Jim, the director compresses the whole to fit within the confines of a movie that is an hour and three quarters long. Truffaut chooses passages from the book and recombines them to create new meanings unique to his production. He alters the real people and events that inspired the original text, to construct a new narrative about female autonomy and fidelity in love, and affords key correspondences between the early pivotal scene on the bridge and the ending. Truffaut also extends beyond the WWI scenes of the book to incorporate his more personal references in the form of veiled and overt references to WWII: he “post-actively” incorporates his memories of his childhood in occupied Paris and his perception of the deep repercussions in France from the collaboration of some of the country’s citizens with fascism.

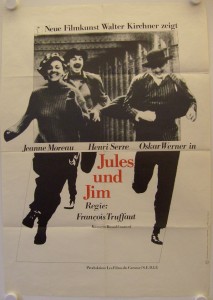

The credit sequence immediately foreshadows Truffaut’s intent. It recontextualizes an incidental dart game played in the book to become a metaphor of sexualized violence: a competition to penetrate a target. The title characters of Jules and Jim are young artists of bohemian Paris before World War I, who compete for the love of their lives. They and their relationships mirror Roché’s own experience. Jim is meant to represent Roché, an extremely influential high cultural connector who, among other networking flourishes, introduced Picasso to Gertrude Stein. But Roché’s acute sophistication and legendary promiscuity are not so present in Jim, in the film portrayed as a man without the courage of his convictions and underplayed by the tall, hesitant Henri Serre.

Jules in reality was Franz Hessel, a German-Jewish writer whose work was banned by the Nazis and who, when he belatedly left Germany for France, was imprisoned by the Vichy government, only to die soon after his release. In Truffaut’s version, Jules is played by Oskar Werner, another reserved actor. Werner has a pronounced Germanic accent, but his character is divested of Hessel’s faith and seems instead intended to obliquely represent fascism. Catherine is Truffaut’s renaming of the book’s Kate, who in turn is a fictional version of Helen Hessel, the writer’s wife and with him equally as socially and sexually dynamic as Roché in intellectual German, Parisian and New York spheres. Truffaut eliminates Kate’s intellectual and social qualifications and changes her name and nationality to be French, but for the part brilliantly cast Jeanne Moreau, who delivered a memorably nuanced and appealing performance.

In the course of their adventures together in Paris, Jules and Jim become obsessed with a projected slide image they are shown of a sculpture of a female head, in a scene that alludes to the power an enlarged, projected image has over on a passive, immobilized viewer, obviously a preoccupation of Truffaut and his fellow New Wave auteurs. Jules and Jim are so taken by the sculpture’s image that they travel to see the object itself, then seek and find its likeness personified in the enigmatic Catherine. The two men commence what appears to be an intimate friendship with the “object” of their desire. In the book and in reality, the three had much more of an overtly sexual relationship together than is seen in the relatively chaste version Truffaut offers.

Intimations of bisexuality and homoeroticism are contained in the scene wherein Jules and Jim dress Catherine as “Thomas” and draw a mustache on her, then let her beat them in a race. The narration says that they are “moved, as if by some symbol they didn’t understand.” These words are transposed from their context in the original text, which give the same significance to the witnessing by Jules and Jim of the flight of a flock of crows.

Truffaut in this scene means to point to the performative nature of sexual identity. Years later, Judith Butler elaborates on the performance of gender to define the symbolism that so mysteriously moves the two men:

“Drag may well be used in the service of both the denaturalization and reidealization of hyperbolic heterosexual gender norms…To suggest that all gender is like drag, or is drag, is to suggest that “imitation” is at the heart of…gender binarisms, that drag is not a secondary imitation that presupposes a prior and original gender, but that hegemonic heterosexuality is itself a constant and repeated effort to imitate its own idealizations. That it must repeat this imitation, that it sets up pathologizing practices and normalizing sciences in order to produce and consecrate its own claim on originality and propriety, suggest that heterosexual performativity is beset by an anxiety that it can never fully overcome, that its efforts to become its own idealizations can never be finally or fully achieved, and that it is consistently haunted by that domain of sexual possibility that must be excluded for heterosexualized gender to produce itself” (Butler, 125).

Truffaut has Catherine allow the men to impose androgyny on her; it even seems to “work” when a passerby asks “Thomas” for a light, but Catherine is indulging the men’s fantasies, or perhaps, teaching them another lesson. She does not want to be a man, she is a woman who wants the rights of a man, she claims autonomy as a woman.

Catherine is an amalgam of many different characters from Roché’s book, but in Truffaut’s version she represents a free person, free to be with who she wants, or not. She seems open to the possibility of a relationship with either man, but by her rules, and she is wary: in front of Jim she burns old letters, saying she “burns lies.” The fire spreads to catch her dress; she nearly immolates herself before Jim extinguishes it. She packs acid into her luggage to “throw into the eyes of men who tell lies” but Jim has her pour the bottle down the sink so it won’t ruin her clothes. Her violence is a defensive threat, or is self-directed. Moreau’s charisma dominates the scenes where all are together and so Jules and Jim apparently “follow” Catherine and indulge her as if she were the leader of a cult. But while Jules is put forth in the narration as gentle and lighthearted, it is he who is manipulative: he is jealous and he is able to control Jim. The initial idyllic phase of their relationship is broken when the two men make their own arrangement in terms of who has “dibs” on Catherine. Jules lays claim, proposing to her and saying to his friend, “Not this one, okay, Jim?” emphasized with a subtitle by the director. It is not a request. Catherine’s power of choice is subverted. Jim acquiesces, thus placing his friendship with Jules over any feelings he might have for her, without considering her wishes. The voiceover says, “Jim thought of Catherine as belonging to Jules.” Roché was not anywhere near as inclined to restraint as Jim is, according to Stam the promiscuous writer considered his penis to be “an unruly creature of independent will” (Stam, 122). Nor was Jules’s counterpart in reality; Stam says that “Jules’ prohibition to Jim in the film—‘Not this one, Jim’–is often read as a demand that Jim not ‘steal’ Jules’ girlfriend, but seen in historical and autobiographical terms, it means they will not ‘share’ this one.” (Stam, 113).

In the scene of the film that most crucially informs Truffaut’s ending, they leave a theatre after attending an unnamed play and as they cross a bridge, Catherine identifies with the heroine who “wants to be free. She invents herself every moment.”

Jules exposes an ugly side of his personality as he speculates about the virginity of the heroine and says, ” the most important factor in any relationship is the fidelity of the woman. The man’s is of secondary importance.” He then cites Baudelaire’s “magnificent…admirable” description of women “in general” as depraved imbeciles who shouldn’t be “allowed in churches. What can they have to say to God?” Jules is saying that women are soulless, something he will repeat later in a letter to Catherine. Jim says he “doesn’t necessarily agree” with Jules’ misogynistic comments. When she says, “Then protest!” Jim weakly says, “I protest.” In a seemingly impulsive action, Catherine jumps off the bridge. She can swim, but it is a dangerous gesture. For his part, Jim is aware that he failed her and he will be haunted by this incident. Jules is in shock; perhaps he realizes that in what he said, in some essential way he has lost her. Words are weapons that wound.

This scene provides the rationale for the ending of the film when Jim and Catherine drive off a broken bridge. The sequences linked by the bridges, by the acts of jumping (as a gesture, an escape or “suicide,” or an “actual” double suicide) as a response to intolerable words, in theatre or film or in an intolerable reality, and in the similarly multiple-view editing of both bridge scenes. The first bridge scene is the crucial lynchpin of the film; however, the body of Truffaut criticism indicates otherwise. Annette Insdorf indicates that Catherine embodies Jules’ assessment of women “in general,” that she is manipulative and negatively capricious: “…Catherine becomes the goddess who is, by definition, a destroyer of men.” Insdorf says that she “jumps into the Seine (because Jules and Jim are not paying enough attention to her)…” (Insdorf, 112). Other critics ignore the meaning of Jules’ comments and the point of Catherine’s gesture similarly: “…she jumps into the Seine in anger at being excluded from the men’s conversation” (Holmes & Ingram, 65). Don Allen also ignores Jules’ words to say that the men “become absorbed in their own discussion.” Catherine’s gesture is diminished to a “…characteristic response…a melodramatic jump into the Seine, accompanied by increasingly sinister music, which frightens and silences him (with reason, as the film’s penultimate sequence makes clear)” (Allen, 97). Allen sees the connection between the bridge scene and the ending, but not its significance. Robert Stam at least recognizes that “Kate’s leap into the Seine is triggered by Jules’ misogynistic reaction to the Scandinavian play, which he interprets as an indictment of women in general.” He notes the pronounced visual correspondences of the two scenes but neglects that the significance of Catherine’s gesture must affect the meaning of the ending.

Despite Jules’ obvious issues with women, Catherine accepts his proposal of marriage, although her reasons are left ambiguous—perhaps it is because she sees Jim as a coward; at least, Jules says what he believes, even if abhorrent. The next Jim hears from them, they are together. Jules barks a crude German-accented version of the Marseillaise to Jim over the phone. Catherine’s choice of Jules as her companion is thusly given more than a hint of collaboration. Both men are subsequently drafted into WWI on opposite sides and spend the whole war worrying that they will kill the other. The men’s allegiance to their nations is greater than their bond of friendship, or their love for her. They are deindividualized, now distinguishable only by their uniforms. Real war footage is used for the trench sequences, as if to say that the war is an overwhelming reality that they must abide beyond their interpersonal constructs.

As with so many of Truffaut’s films, in Jules and Jim there are layers upon layers of references to writing and reading books and letters. Catherine mocks Jules when she describes an absurd theory she just read in “a book by a man, of course, a German, who dares to say out loud all the things I’ve thought quietly.” Jules’ implication on the bridge that Catherine is soulless is restated in a letter he writes to her from the front: “My love, I think of you ceaselessly, not of your soul, for I no longer believe in it…but of your body, your thighs, your hips. I think of your belly, and of our son who is inside it. As I have no more envelopes, I don’t know how to get this letter to you.” She is to him an envelope, an empty, sexualized container, an object for filling. This objectified concept of a woman is echoed elsewhere in the film when Jim is introduced to an affectless woman in Paris, who is dehumanized by her companion as “empty…just a thing.”

After the war ends Jim visits Jules and Catherine, who now have a child together. She only is with him for his outwardly “indulgent and leisurely ways.” She asserts her own freedom by having overt affairs and even leaves him and her child for months. Jules asks Jim to be with Catherine because he is afraid someone else will take her away and she will be lost to him forever. Love is a paradox, though. While Jules apparently will do anything, accept any infidelity rather than lose contact with Catherine, Jim never seems to show enough passion for her that it overrides his other romantic relationship, or even his friendship with Jules. But the integrity of that masculine bonding is in question as well, since Jules laid claim without regard for Jim, and although Jim allowed Jules to “claim” her, he resents it. Jim does not truly respect Jules’ feelings, because before his friends’ marriage, he had taken the chance to meet Catherine at a café on his own. In that scene, the narration says that “with his usual optimism, Jim had arrived late at the cafe.” But when she is not there, he does not wait unduly past a certain point —he is impatient; he has a few drinks and then gives up and leaves, right before she arrives. She had just been to the hairdresser, to enhance her appearance for his benefit. One could say that he fails the test again. After Jules begs Jim to stay with Catherine, she takes him as her lover, however, he is not so amenable to her percieved changability as Jules. She tries an experiment, going back to Jules one night and Jim is consumed by jealousy. This scene is enough to make him reconsider the arrangement.

Catherine will not accept less than full commitment from Jim, but he vacillates in his attentions to Catherine with his affections for his fiancée Gilberte. When separated, Catherine and Jim both write letters to each other that seem written to imaginary ideals. He treats the patient Gilberte badly by expecting her to endure his indecision. He is unable to fulfill a relationship with Catherine that because of his inaction over years has become conflated in their imaginations. When Catherine and Jim are unable to conceive together, he says he will be able to have children with Gilberte, and so he gives up on their relationship. Perhaps it was always Jim she wanted, but he has no courage in love and he tells lies, firstly to her in denying his love for her by conceding her to Jules, then to her now and even to Gilberte, by making them think he loves her, when actually he is only another man like Jules, who wants an envelope/receptacle.

Significantly, the enraged Catherine this time forces him to jump, out of a window after she threatens him with a gun. Jim goes back to Gilberte and Catherine goes back to Jules. One night Jim wakes to see Catherine driving madly in erratic spirals in the plaza below his apartment, echoing with her vehicle the words of her song, Le Tourbillon. Years pass.

Click to watch the final 4 minutes of Jules and Jim

In the final meeting of the three, they are coincidentally all in a theatre watching a newsreel of Nazis burning books, again hyperrealized with documentary footage. They drive to a cafe and Jules says, “Now they are beginning to burn books.” Catherine’s only remaining connection to Jim is bound up in text; as she said in a letter to him, “This paper is your skin, this ink is my blood.” The Germans burning books will soon be burning people. She knows the two men might be forced into service for their countries again, they surely went last time. She asks Jim to take a ride with her. She tells Jules to “watch us carefully” and together Catherine and Jim calmly drive off a broken bridge to their deaths.

They both end consigned to the incinerator by Jules, detailed at the end of the film as an methodical process that can be seen as a metaphor for the concentration camps of WWII. Since he cannot have things the way he wants them and could not control Catherine, Jules is selfishly happy now that she and his friend are dead; he is relieved of the weight of loving them. But it is Catherine who is usually described in critical essays as the destroyer, a murderess who rips friends apart and drags Jim down to his death in a pointless display of caprice. However, she clearly offers Jim a choice and he has no affect of fear as they drive to the precipice. The way this is shown in the film is that the camera becomes a view through Jim’s eyes. Catherine turns and smiles at us and as they reach the precipice, the camera jiggling and from the same viewpoint, Jim’s eyes are reflected in a mirror on the sunguard. He is expressionless. As with her earlier jump from the bridge, this is meant by her as a lesson, this time intended for Jules, since she directs him to pay attention. He does not comprehend the reason for their act, he is simply now free from the weight of his jealousy.

Genevieve Sellier notes that Alexandre Astruc, the filmmaker who articulated the malleable-in-process camera stylo methodology which the New Wave auteurs used, also initiated “the dominant reign of a male annunciator that reduces the female character to a fantasmic projection” in his first film, the 1952 Le Rideau cramoisi (Sellier, 83). Astruc’s films put forth a narrator, an “insistent masculine presence that functions as the auteur’s point of view” (84). Truffaut’s use of a male “narrator-witness” in Jules and Jim represents a “male gaze,” but Truffaut subverts the narration which is taken primarily from the text source by empowering Catherine through his own imposed plotting and Moreau’s sympathetic interpretation to put the lie to the spoken text. The narration directs the viewer, but is not always in synch with what the viewer is seeing. Something said with authority does not necessarily have to be taken as fact. The viewer is asked to sympathize with Jim, but instead empathizes with Catherine, and oddly, Jules, more than with Jim, who yet provides the focus of the male narration, as it is done in Roché’s authorial voice.

The narration from the very start of the film tips Truffaut’s hand as to his motivations. The viewer hears Catherine’s voice saying, “You said to me: ‘I love you.’ I said to you: ‘Wait.’ I was going to say: take me.’ You said to me: ‘Go away.'” This serves as an epigram, a quote presented at the beginning that lays out a way of reading the subsequent story, in which Jim makes Catherine wait for him, but in the end abandons her. Her first leap from the bridge was her “going away” at his request by his complicity with the denial of her human status when Jules claimed her to be a soulless monster. After the credits roll and a scene of Jules and Jim playing dominos that is shot to look like a Cezanne painting, they have a bonding epiphany which occurs in a costuming shop. The narration says,

“It was about 1912. Jules, a stranger to Paris, had asked Jim, who he hardly knew, to get him into the Quatres Arts Ball. Jim had gotten him an invitation and had taken him to the outfitters. It was as Jules was rummaging in his gentle way among the materials, choosing for himself a simple slave’s costume, that the friendship of Jules and Jim was born. This feeling grew during the ball itelf, where Jules looked on quietly, his large round eyes full of gentleness and good humor” (Jules and Jim, 11, 12)

In four sentences the viewer is told not only that they are supposed to sympathize with Jules because he is “quiet” and has “large round eyes,” it is told twice how gentle he is. However, his appearance is as deceptive as is that of the other characters. Jules here is immediately shown in his performative mode, “choosing” to represent himself as a “simple slave,” as he does to Jim later when he fears he is losing Catherine.

If one undermines Truffaut’s plot by applying a male-centric “gaze” to it, one might take the narration at face value. An early review attributed by Sellier* to Claude Mauriac of Le Figaro littérraire set a misogynist tone for the “reading” of Truffaut’s film:

“Jeanne Moreau has an overwhelming presence. She has upset the equilibrium. Out of a film about friendship, she has made a film about love. And more seriously, out of an auteur film, an actress’s film…It’s too bad, because what draws us to the story is not this pretty, egotistical girl, …but the two boys: modest, discrete, generous” (Sellier, 194).

A critical stance that celebrates male bonding at the expense of the objectified female the men feel free to pass between them, might also serve to make subsequent viewers and critics predisposed to form an opinion on the purpose of the film based on the idea that Catherine is shallow enough to jump from a bridge simply because the two great friends are ignoring her.

Sellier herself misreads Catherine and confuses the character with the actress who portrays her:

“…despite the impression of authenticity and liberty created by Moreau’s acting and her physical appearance, the image of the woman constructed…seems to be located at a great distance from any social modernity, in order that the feminine be associated entirely with amorous passion, out of space and time. The figure of the modern woman chosen by the cultivated classes, Moreau at the beginning of the 1960s, embodies an image of the feminine that associates sexual freedom with death” (198).

This not only exhibits a form of reverse classism, it objectifies the actress and negates Catherine’s interiority and any of her other qualities that do not have to do with her sexuality.

The film was released at the dawn of the sexual revolution and its characters have been taken as icons of sexual liberation, but this is partly because in the response to the film, the director’s intent has been ignored and the story’s symbols have been critically divested of feminist intent. The film is popularly seen as representing a simultaneous three-way sexual relationship. It was that in Roché’s book and in his experience. However, in Truffaut’s relatively chaste movie, the relationships shift in alignments, but never meld. Instead, in a way that wouldn’t be controversial if Catherine was a man, she claims autonomy and the ability to choose a companion for herself. Although it appears that she expects allegiance from both notwithstanding her shifting attentions, if anything she uses Jules to try to elicit the desired response from Jim, to get him to admit his love for her. But he is not there for her and war might take them both again to become dehumanized killing robots for their countries. Catherine’s last gesture is informed by Truffaut, who alters the ending so that she responds to militarism and nationalism, to the holocaust to come that will be carried out by men like the “gentle” Jules. She opts to stop “collaborating” with Jules. Jim backed away when Jules told him to, and did not defend her against Jules’ sexism, but he finally stands with Catherine and proves himself by joining her in her final protest.

The issue of collaboration imprinted on Truffaut because he grew up in occupied Paris. Neighbors were set against each other in an atmosphere of real danger that paradoxically was made to appear as if it was normal. Truffaut and his contemporaries interacted with their environment with the innocence of youth, but later learned the Nazis’ purpose when the concentration camp footage came out. The revelations, told through the means of cinema, produced a sickening disjunction between their perceived reality and an incomprehensible nightmare. An awareness dawned that people who commit and support unspeakable acts can seem as if they are unremarkable.

In Paris, the Nazis kept up the appearance of business as usual. Truffaut touched on this elsewhere, as in The Last Metro, when in the opening scene set on a Paris street in the Occupation, a strolling Nazi soldier gently ruffles the hair of a passing French boy. Perhaps in the end Catherine takes the side with Jim of France. After the essentially glad-to-be-rid-of-them Jules disposes of their ashes in oblong, peaked urns that resemble the faceless buildings of the concentration camps.

The camera then tracks Jules’ figure as he marches jauntily away down a hill, his steps synchronized to the strains of Le Tourbillon, now at a tempo to become sentimentally militarized. One almost expects him to jump and click his heels. Truffaut takes a lot of artistic license with a character based on a man who suffered at the hands of the Nazis, and as a result died long before his two dear friends.

If there is a courageous experiment in Jules and Jim, it is in the creation by Truffaut and Moreau of the character of Catherine, who tries to transcend the limitations that men impose on women. Throughout the film, both Jules and Jim treat Catherine as an object of desire. For her part, Catherine constructs an ideal of Jim, one that he doesn’t reflect until the very end. Jules harbors jealousy and resentment and learns nothing, but Jim tries to make amends for his complicity with Jules against her, by giving his life to stand with her. Truffaut’s version of a Jim who can sacrifice himself for one woman is far removed from Roche, who was the embodiment of “Don Juan,” who Stam says engaged in “amourous imperialism” and who opined on theology: “I can concieve only of a God, who, in his own way, does with the world what we do with the women he has given us” (Stam, 28). Catherine’s gestures are formed as expressions of Truffaut’s realization of how close one can be to utmost evil and not recognize it. Faced with a male-dominated world that crushes love, whether embodied by the resentments and complicities of Jules and Jim, or by their states that wage war without end, Catherine literally drops out.

In 1962, Jean Renoir wrote a letter to Truffaut about Jules and Jim:

“In a few years we’ve gone from one civilization to another. The leap is more formidable than the one made by our forefathers between the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. For the Knight of the Round Table, sentimental adventures were the subject of great fun, for the Romantics, the pretext for a flood of tears. For the characters in Jules and Jim it is something else again, and your film contributes to making us understand what this ‘something else’ might be. It is very important for us men to know where we stand with women, and equally important for women to know where they stand with men. You help dissipate the fog that envelopes the essence of this question.” (Quoted in De Baecque and Toubiana, P 181).

Renoir understood Truffaut’s effort to empathize with Catherine while allowing the audience to distinguish the actuality of his message from their more prurient expectations. Taking as a starting point “the most scandalous situation there can be,” Truffaut said he tried to “bring off a film about love that would be as ‘pure’ as possible, and to do that through the innocence of the three characters, their moral integrity, their tenderness, and above all their sense of decency” (Truffaut by Truffaut, 75). In the context of Jules and Jim and in the real world, mustard gas and genocide are violations of decency, not the private lives of a few individuals. The pureness Truffaut sought transmuted into something else through his auteur process, but as he said, “when at times fiction takes us far from real life, all of a sudden we say what we think, we rescue ourselves by sincerity” (76).

The triadic relationship is illusory in the film, as such relationships often are in reality, although this may be because we have not evolved to the point that we can transcend socialized prejudices based on our superficial physicality. Alas, deeply-imbedded male-centric prejudices also informed the promotion of the film and most of its critical response, which continues to inform subsequent perceptions, to the extent that no one else but Renoir has seemed to get the point. The fog is dissipated but the essence remains. The suppression of women is the longest-standing inequity, and we are always only a few steps away from World War III.

_______________________________________

My thanks to Philip C. Watts and Marguerite Van Cook for their invaluable advice on this piece.

_______________________________________

* Appendix Two in Masculine Singular lists Claude Mauriac, an supporter of Truffaut’s own criticism and his earliest directorial efforts, as the cinema columnist for Le Figaro littérraire, but gives the time of his tenure there as “(1946-1957)” (Sellier, 228). Jules and Jim was “first shown in Paris, 23 January 1962” (Allen, 226).

_____________________________________

Bibliography

Allen, Don. Finally Truffaut. New York: Beaufort Books, 1985.

Butler, Judith. Gender is Burning: Questions of Appropriation and Subversion. Bodies That Matter: On the Discursive Limits of “Sex.” New York: Routledge Inc.,1993, pp. 121-140.

Holmes, Diana and Robert Ingram. François Truffaut. Manchester U. Press, 1998.

Insdorf, Annette. François Truffaut. New York: Touchstone, 1989.

Sellier, Genevieve Sellier. Masculine Singular. Trans. Kristin Ross. London: Duke U. Press, 2008.

Stam, Robert. François Truffaut and Friends. N.J.: Rutgers U. Press, 2006.

Toubiana, Serge and Antoine De Baecque. Truffaut. Trans. Catherine Temerson. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1999.

Truffaut, Françoise. Jules et Jim (screenplay). Trans. Nicholas Fry. London: Faber and Faber, 1968.

–Truffaut by Truffaut. Ed. Dominique Rabourdin. Trans. Robert Erich Wolf. New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1985.

I have quite a few issues with James’ interpretation here, but I must acknowledge his insight and intelligence.

I incinerated my father at the selfsame cemetary, Père Lachaise, in 2007. Does that make me a metaphoric Nazi?

Speaking of book-burning…this came back in a very overt way, of course, in truffaut’s version of Bradbury’s ‘Fahrenheit’. Truffaut did something rather clever there– in the book bonfire scene, he made sure a wide diversity of controversial books were thrown on the blaze, rightist, leftist, religious, atheist…he stated that he wanted the spectator to think, “Well, that one deserved to be burnt!” Thus making him an accomplice…

The idea of book-burnings leading to people-burnings is most famously expressed by the German-Jewish romantic poet Heinrich Heine:

“Das war ein Vorspiel nur, dort wo man Bücher

verbrennt, verbrennt man auch am Ende Menschen.”

(1821)

Gee, Alex, if you had manipulated the hell out of him and denied his humanity, then whilst consigning him to the flames you were relieved and happy to be rid of him and nearly danced a jig on your way out, I would say…maybe?

But since it’s unlikely that you felt that way, then no.

In a typical example of the cross-referencing that is seen across Truffaut’s films (and after a few false starts with other actors), Truffaut used the same actor who played Jules, Oskar Werner, to play the book-burning fireman Montag in Fahrenheit 451, his Germanic accent again emphasized. In that film Werner again is part of a triangular relationship, this time with Julie Christie playing a dual role.

And yes, in that film one can see a copy of Mein Kampf burning along with all the great works of literature.

Julius doesn’t march jauntily away, though. He just walks away.

Sorry, Alex, my first response must have read as insensitive. Of course, not every cremation has that association. The film sets up characters in specific circumstances that lead me to make that connection.

To write that piece, I did not read anything about the film before I saw it recently. I made notes on my initial observations, then read up on the film (although I couldn’t read the French literature about it). I then cross-referenced my own, relatively objective take with the other information at my disposal. I could be misreading the finale but then, the “sentimentally militarized” lilt of the music and Jules’ lightened step are pretty subtle. At any rate, in this case his words speak clearly to his relief at the deaths of his friends.

James, no insensitivity was shown on your part; I’m the one who brought it up!

More bizarre, to me, is why I called Jules ‘Julius’…I was probably thinking of groucho…

Thanks for this great essay James — makes me want to go back and watch this brilliant film right now. I think it’s been over a decade…

Thank you for a well written critique of the film. I found myself disliking Jules and Jim because Catherine was being objectified during the film, as were other women.

I guess she showed them.