“When the critic has no delicacy, he judges without any distinction, and is only affected by the grosser and more palpable qualities of the object: The finer touches pass unnoticed and disregarded. Where he is not aided by practice, his verdict is attended with confusion and hesitation. Where no comparison has been employed, the most frivolous beauties, such as rather merit the name of defects, are the object of his admiration. Where he lies under the influence of prejudice, all his natural sentiments are perverted…Strong sense, united to delicate sentiment, improved by practice, perfected by comparison, and cleared of all prejudice, can alone entitle critics to this valuable character; and the joint verdict of such, wherever they are to be found, is the true standard of taste and beauty.”

“Of the Standard of Taste”, David Hume

Over the past few weeks, several eyes will have been directed to a much praised article by Gary Panter on the ineffable skills of Jack Kirby. It will, undoubtedly, be in the running for one of the best pieces of comic criticism written this year.

It is a short piece with a specific intent, namely to highlight the nuts and bolts of Kirby’s (and Mike Royer’s) craft: his use of lighting; the quality of his forms; the application of the inker’s brush. A common enough critical approach in artist monographs, but one strangely lacking in the discussion of comics. It is, perhaps, a gentle effort to investigate the essence — that distinctness, that aura — of Kirby’s art.

Panter is, of course, an artist, and Alex Buchet offered the following observation in relation to such encounters :

“There’s a well-known saying about the military: ‘Amateurs talk strategy. Professionals talk logistics.’ By analogy, in art I’d say: ‘Amateurs talk art, professionals talk craft’. The painter/sculptor/installer Soto told me that art consisted of solving problems. Artists are all deeply involved in detail.”

But comics are more than mere pictures. One might equally ask why writers so often neglect (perhaps purposefully) to address the basics of the writer’s craft. Why don’t critics (writers by trade) address the grammar of comics writing, or the structure and flow of sentences with any degree of frequency? Why don’t critics discuss the vocabulary of the writer with any semblance of depth or persistence?

This may have something to do with the realization that artistic worth cannot be adequately described or conveyed by this cleaving to craft and engineering, fascinating as these cogs and wheels may be. In writing his famous biography of J.S. Bach, the organist and music scholar, Albert Schweitzer, was similarly concerned with the qualities of the composer’s craft: the structure of his preludes and fugues; the nature of his counterpoint and ornamentation. Yet his central thesis — addressed right from the outset — is somewhat divorced from these proceedings (and to this he keeps returning):

“Some artists are subject, some objective. The art of the former has its source in their personality; their work is almost independent of the epoch in which they live. A law unto themselves, they place themselves in opposition to their epoch and originate new forms for expression of their ideas. Of this type was Richard Wagner. Bach belongs to the order of objective artists. These are wholly of their own time, and work only with the forms and the ideas that their time proffers them. They exercise no criticism upon the media of artistic expression that they find lying ready to their hand, and feel no inner compulsion to open out new paths.”

Now many scholars and critics will be of the opinion that Kirby fits the mold of the “subjective” artist, but to my mind, Kirby is of the latter class. He did not originate the action-adventure form in comics (an honor which might be accorded to Hal Foster or some other) and was happy to mete out his days in the tried and true formulas of the superhero genre. His stories could never be considered innovative in form by the measure of all narrative art, and his myths were cribbed from the popular legends and detritus of the times. As with Bach, this classification does not automatically denote a lesser artistic achievement on his part.

Schweitzer addresses Bach’s greatness from within these boundaries; here in his description of Bach’s cantatas and Passions:

“Out of the motet, under the influence of Italian and French instrumental music, came the cantata. from Schutz onwards, for a whole century, the sacred concert struggles for its free and independent place in the church…It forces itself further and further out of the frame and service, aiming at becoming an independent religious drama, and aspiring towards a form like that of opera. The oratorio is being prepared. At this juncture Bach appears, and creates cantatas that endure… As regards their form, his cantatas do not differ from the hundreds upon hundreds of others written at that time, and now forgotten. They have the same external defects; they live, however, by their spirit.”

“At the end of the seventeenth century the musical Passion-drama demands admission into the church. The contest rages, for and against. Bach puts an end to it by writing two Passions which, on their poetical and formal sides, derive wholly from the typical works of that time, but are transfigured and made immortal by the spirit that breathes through them.”

This “spirit” is indefinable. It may in fact be supported by prejudice (as later writers have accused Schweitzer of in relation to his somewhat lower opinion of Telemann). It has little or nothing to do with trills, mordents and cadences. And despite reams of erudition discussing the play of word and tone in Bach, and the musical language of his chorales and cantatas, Schweitzer professes a loss for words when faced with The Art of Fugue:

“The contrapuntal art that it reveals is so perfect that no description can give any idea of it.”

The same may be said of the art of Kirby; his art not reducible to lines and lighting nor any kind of esoteric phrasing or lack thereof. Panter’s article is an act of detection which starts at the point of first impression, and yet never departs from it; not an exercise in futility but one with a more practical intent than a judicial one, for the latter can never be accounted by this approach.

Yup: if a critic describes a work of art s/he describes a work of art. In other words: s/he says absolutely nothing about it.

This sort of speaks to the Spiegelman thread, doesn’t it?

As usual (and kind of to my sorrow) I can’t be quite as hard core as Domingos; I think description is a legitimate critical function…even an important part of criticism. So not nothing (at least to my mind.) But I do agree that confusing description with evaluation, or thinking the first can substitute for the second, leads to unfortunate places.

I feel a bit uneasy reading this, Suat, as I’ve just posted a review of a page of Winsor McCay’s that, apart from some perfunctory waffle, is a nuts-and-bolts examination of craft– treating the art as a piece of engineering.

At one point I was going to run the article by you, but perhaps it’s better that I didn’t– I might have given up.

Excellent post, btw. Great art has this numinous mystery about it that can’t be dissected…

Alex: I would never have discouraged you from doing that piece! I felt entitled to write this down because I do this kind of nuts-and-bolts examination all the time. But it’s good to stand back and consider what you’ve done once in a while.

Noah: Yes, it does relate to the Spiegelman discussion but, as you know, I generally try to avoid discussing Maus whenever possible.

One might also ask in relation to this where theory and theoretical analysis leads to; and when Caro says that “…the theoretical question isn’t whether a comic makes a meaningful formal or aesthetic achievement. The theoretical question is whether the forms of comics conform to or challenge the theoretical concept,” are we to assume that theory is an end itself (a kind of wavering truth), or purely a logical-philosophical system to wring dry life and art?

Let’s see if I understand the program being offered: biography is not criticism, description is not criticism, historical context is not criticism, academic theory is not criticism. What is criticism? Making a short list of who belongs on the island and who doesn’t. Survivor is the model of criticism.

Let me offer a counter argument: the act of exact description doesn’t just happen naturally: it’s a skill and approach that developed over time as a result of theories like empiricism and the rise of the scientific method. Every act of description carries within it an implicit judgement, since it’s saying that this is something worth paying attention to. The judicial mode of criticism is for people who want the authority of being judges without doing the hard work of description (or historical analysis or theoretical analysis).

The great descriptive critics — I’m thinking here of Ruskin, Pater or John Updike — are in fact doing something very difficult: using words to describe images so as to educated the reader’s eye. You look at paintings differently after reading Ruskin, Pater or Updike. In his own small way Panter was doing the same with Kirby (with all allowances made for the fact that he was writing very briefly about one panel). To dimiss this approach is myopic in more ways than one.

“the act of exact description”

This doesn’t exist.

” it’s a skill and approach that developed over time as a result of theories like empiricism and the rise of the scientific method. ”

But empiricism and the scientific method really don’t work especially well when applied to art. Making aesthetics into some kind of poor stepchild of science seems like a pretty depressing gambit in any case — and opposed to the last more-than-a-century of aesthetic theory as well.

” Every act of description carries within it an implicit judgement, since it’s saying that this is something worth paying attention to.”

But it doesn’t say why it’s worth paying attention to. It could be worth paying attention to because it’s pernicious and needs to be crushed. It could be worth paying attention to it because other people are paying attention to it. It could be worth paying attention to because it fell on your head this morning. It could be worth paying attention to because that’s a way to get tenure. Or because you’re in an argument and somebody cited it. Or whatever. If you don’t say where you’re coming from, the mere fact that you’re talking about something won’t fill the gap. Or…it will fill the gap with unexamined prejudices and easy hagiography.

“Let’s see if I understand the program being offered: biography is not criticism, description is not criticism, historical context is not criticism, academic theory is not criticism. ”

I’d prefer to think of it in terms of good or bad criticism rather than in terms of what is or isn’t, at least usually.

But don’t forget interviews! They’re not criticism, damn it.

“‘the act of exact description’

This doesn’t exist.”

So Ruskin doens’t exist. Pater doesn’t exist. Updike doesn’t exist. Only this blog exists. A solipsistic universe if ever there was one.

Of course no desription is perfectly exact, but that doesn’t mean that some critics aren’t more skillful at description than others. In his book A Homemade World, Hugh Kenner has a few interesting paragraphs outlining the history of visually descriptive writing, focusing on Ruskin. Worth tracking down.

Jeet, I’m not sure who you are responding to but it doesn’t appear to be me (maybe Domingos and Noah?). As such I find it somewhat difficult to respond to your points. This blog entry was not an effort to exclude any piece of writing from the hallowed halls of “criticism”. In fact, my second line clearly states that the Panter piece will undoubtedly “be in the running for one of the best pieces of comic criticism written this year.”

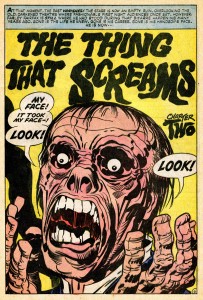

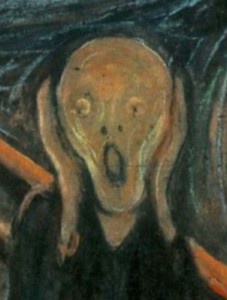

I was merely trying to affirm the limitations of the purely “descriptive” approach. Can it, for example, allow us to determine which of the three images above is of the most lasting value without recourse to something less than objective? Would Panter’s approach (interesting though brief as it is) allow us to do this?

The authors exist (more or less; without bringing Foucault into it). What they’re doing isn’t exact description.

Some description may be more exact than others. But that’s an evaluative distinction, not an objective truth.

And, yes, only this blog exists. That’s why your writing here is so much more entertaining than anywhere else!

“Can it, for example, allow us to determine which of the three images above is of the most lasting value without recourse to something less than objective?”

I don’t think it makes any sense at all to judge these three images by the criteria of “the most lasting value” since they have different functions: a comics panel, a movie still and a painting. The painting is meant to be viewed as a single image, the movie still and panel are part of a larger work. The type of picture production that Kirby and other cartoonists do (prolific and sequential) is different is different in intent from the picture production of painters (slow and as a single unit), and is seen differently by viewers. The reading protocals or viewing protocals are different. The whole question really seems meaningless to me; it’s another way of asking who is stronger, Superman or Jesus?

What makes Panter valuable is that even though he’s focusing in on a panel, he’s aware of the context of the image as part of a comic book and Kirby’s work; Panter’s comments illuminate both the panel and Kirby’s wider artistic practices.

Well, Panter would have to be pretty dim not to realize that he was pulling an image out of a comic book. But if you read the second to third paragraphs of Panter’s piece you will find that he doesn’t address the panel’s place within the comic to any great extent (though for one brief moment, he does try to connect the flaking flesh to Kirby’s possible emotional state at that point in time).

If anything, Panter is looking at the panel as a single image, bringing in references from contemporary fine art (“pop art and super-realist painting)’), and then film noir and expressionistic German film. His intention is clearly to emphasize Kirby’s qualities as an artist of the single image. In fact, that may be the chief virtue of Panter’s article, his insight into the technical aspects of Kirby and Royer’s drawing without recourse to the narrative power of the comic.

“it’s another way of asking who is stronger, Superman or Jesus”

But this is a hugely important question! Far more consequential and fraught than the question of which of the works above have lasting value (though not unrelated in its evaluative aspects.)

Comparing Superman to Jesus touches on questions of modernity, ethics, spirituality, pacifism, the place of human beings in the world, the nature of God.

I think it’s a very astute point on your part to use that as the metaphor for why it’s not interesting to discuss evaluative criteria. If you start talking about evaluative criteria, you do have to move to questions of ethics, spirituality, the place of human beings in the world, the nature of God. Those things are subjective, but they’re the most important parts of us too. They’re much more interesting conversations, to me, than reading protocols…but obviously different strokes….

For me, what an artist does with earlier art (the way he or she learns from and refashions inherited traditions) is more interesting than the question of an artists stature within some imaginary canon. What makes Panters piece strong is that he emphasize Kirby’s artistic practices, what Kirby is doing with images. It’s notable that there are many active verbs in Panter’s piece: “making crazy comics … uses the compositional strategy … Kirby puts us so close to the monster’s point of view… [t]he face is constructed of a tangle of highly orchestrated thick and thin calligraphic brush marks … Kirby also does an interesting thing with his thick and thin outlining….etc.”

Panter emphasizes artistic practice, on art as an activity, a form of making and doing. This approach is a very useful as a corrective to the dominant tendency to see art as a fixed and static thing, a set of images on the wall that we are supposed to evaluate and grade by some abstract category (“lasting value”).

For Panter, art is a verb; for the critics here at HU art is a noun (or perhaps a sheepish and dull-witted student that needs to be corrected). That’s a crucial difference.

“For Panter, art is a verb; for the critics here at HU art is a noun (or perhaps a sheepish and dull-witted student that needs to be corrected). That’s a crucial difference.”

See? Evaluation! You keep doing it when you’re not looking!

According to your own lights, you shouldn’t be comparing us to Panter in order to denigrate us. Instead you should be providing exact descriptions of our practice, reveling in specificity — like, for example, teasing apart which critic is which (perhaps by referring to the handy names at the top of each comment.)

But I think your approach in this comment is actually more valuable. I like the emphasis on making and doing and the forthright evaluative rejection of abstraction. Not new, but presented with verve.

Jeet: What Panter is doing is adding his voice to those who put Kirby in the canon. To him a great formalist is automatically a great artist. That’s what you find so boring and fascinating at the same time.

Forget everything else… Forget even the fact that he wasn’t the only author of the image.

My favorite part in Panter’s text is, obviously, the one in which Panter puts some emotional melodramatic feeling in the image.

Suat:

“[…]when Caro says that “…the theoretical question isn’t whether a comic makes a meaningful formal or aesthetic achievement. The theoretical question is whether the forms of comics conform to or challenge the theoretical concept,” are we to assume that theory is an end itself (a kind of wavering truth), or purely a logical-philosophical system to wring dry life and art?”

Both, alas.

The delusion that art exists solely as a food to be gorged upon by theory has swept all before it.

To iterate a parallel I’d made before: just as Man was not made for the Sabbath, but the Sabbath for Man — Art was not made for Theory, but Theory for Art.

It is grotesque that art– even bad art — should be strapped to this bed of Procrustes merely to accomodate the dreams of tenure of basically parasitic aesthetic drones.

But such are the times we live in.

Kids today…tsk, tsk…

But theory’s art too! Much of it isn’t even parasitic in the sense Alex means; it’s philosophy, and not necessarily even attempting to explicate a particular aesthetic object.

I did sort of respond to Suat’s question here.

I honestly think the question makes sense mostly because of the disciplinary situation right now, with literature in particular so blurred into philosophy. There’ve always been philosophers, and there’ve always been philosophers who have written about art. Less counterintuitively and politically than the ones that fall under the rubric of “theory”, absolutely, but still writing about art. And their writing tended to be philosophy more than it was criticism. Theory’s just the latest incarnation of that.

But as I mentioned previously, the philosophy that falls under the rubric “theory” tends to be pretty anti-humanist, suspicious of the politics and power dynamics of any aesthetics. That makes it less cozy bedfellows with art than most of the older philosophical approaches to art.

So I don’t think theory is either an end in itself or a logical-philosophical system to wring life and art dry. I think it’s intended to turn life and art inside out and show their seams, though, and that close lens can and probably does destroy a lot of the conventional ways of getting pleasure from a work of art.

That’s why there’s this sense that it wrings the art dry, and that’s why it’s important that people think specifically about that consequence, as Suat invites us to do. But I don’t think that effect means there’s no pleasure left — the pleasures post-theory are just different. And different works appear maximally pleasurable when viewed through that lens. That’s the pluralistic effect that’s so important to theory’s political stance.

=========

Noah, Alex, clearly just has no idea what “theory” is. I have no idea what he’s imagining — it appears to be just bad academic writing — but it’s clearly something different from what theory actually is (which is, very specifically, Continental philosophy after WWII.)

If early poststructuralism, for example, is parasitic on anything it’s on Plato, Hegel, Husserl, Levinas, and Saussure. Their works are the primary texts for Derrida’s first 4-5 significant works. With the exception of Levinas, who is mid-century, and Saussure, who is a linguist, those writers are all plain old canonical philosophers. Now, indeed, they all wrote directly about art, theorized how art made sense, how it affected us, how it shaped our reality. So maybe he means they are the parasites? Hegel, whose Aesthetics is generally considered to be as important as Aristotle’s Poetics; Levinas, who claimed that art “expresses the very obscurity of the real”; Saussure, who gave us a theory of semiotics as an alternative to aesthetics; and Plato, for whom beauty was the most exemplary of the forms.

If Alex were actually talking about Theory rather than some apparition he thinks is theory, he’d be saying that these writers, who are as significant to Western thought as Shakespeare or Nabokov are to Western writing, are “parasitic aesthetic drones.”

Um, whatever.

Or perhaps he means Derrida — who wrote about those writers, challenged their logic and their place in our culture, turned a hybrid protocol combining the techniques of literary close reading with the proof models of formal logic against them to formulate the theory of the Supplement, thereby synthesizing them into each other in an absolutely exemplary Hegelian dialectical move — perhaps he is then the parasite on Art. On art, really? Not on philosophy itself?

If that’s what Alex means, then all disciplinary debate and discussion, all close reading, all critical engagement and the evolution of scholarly thought is parasitism too.

Um, WHATEVER.

Theory does not “gorge” on art at all. It’s not a parasite – it’s a plant, rich with intellectual chlorophyll, that makes its own food from light.

Alex, if you want to see all that as parasitism, yeah, whatever.

Caro:

“Noah, Alex, clearly just has no idea what “theory” is. I have no idea what he’s imagining — it appears to be just bad academic writing — but it’s clearly something different from what theory actually is (which is, very specifically, Continental philosophy after WWII.)”

No, that’s just an arbitrary tag used by practitioners of certain academic disciplines to appropriate a word that properly belongs out of their exclusionary hands, and back in the intellectual commons of humanity.

I find it amusing that there’s no parallel usage of “theory” among French academics, given how Anglophone practitioners of “theory” draw so extensively on French thinkers.

Of course, what you describe as “theory” doesn’t begin to include all post-war continental philosophy. Where is Sartre in the mix, for instance?

As I mentioned before, you’re welcome to suggest another word.

But your semantic arguments are pointless unless you actually acknowledge they’re about semantics. You want it called something else, say what you want it called instead. But you’re just not powerful enough to single-handedly change what it means in academia by fiat, nor to render the concept of professional jargon non-operative. Sorry.

Plus, if you were actually paying attention to your continental philosophers, you’d know that all words are “arbitrary tags,” and that pretending you can assert anything else is entirely missing the point.

As for Sartre, I gave you one illustrative example of possibly hundreds. I also didn’t mention Deleuze or Foucault or Merleau-Ponty or Levi-Strauss or Marcel Mauss or Cornelius Castoriadis or Antonio Gramsci or the any feminist philosophers or myriad myriad others — including any of the Germans in the Frankfurt School and Hannah Arendt and Jurgen Habermas. I am most versed in poststructuralism so it’s the example that came most easily to mind. But “theory” does not mean just poststructuralism as you are implying. The term does in fact emcompass, with varying degrees of practical application, all post-war Contintental philosophy.

Sartre was, however, as much a literary writer as he was a philosopher. Although this makes him solidly a predecessor to writers like Irigaray, to no small extent it, along with the critiques of his work by Foucault and Derrida during their lifetimes, has put him on the edges of the conversation. There has been a good bit of scholarly effort recently to resituate him with regards to Derrida and Foucault’s critique and draw the more resonant connections. A google scholar search for the names in concert should pull up enough to answer your question, if you actually care.

Ng, I was as impressed by “Short Thought for the Day: What Art Will Last?” as I was, alas, underwhelmed by the Panter piece. That “will, undoubtedly, be in the running for one of the best pieces of comic criticism written this year”? Oy!

———————

Noah Berlatsky says:

“the act of exact description”

This doesn’t exist.

———————–

Certainly not in a Platonic sense of über-exactitude. Can’t help but be reminded of the Borges fable of an ultra-precise map, every bit as large as the terrain it delineated.

Back in the real world, though… Sure, one can’t describe every single facet of an object, situation, or work of art. But, can’t one be precise when dealing with certain details? I.e., “the bolt is six centimeters long,” “the alleged thief was seen standing close to the jewel-case,” “there was broken glass spread across the street.”

————————

Jeet Heer says:

Every act of description carries within it an implicit judgement, since it’s saying that this is something worth paying attention to.

————————-

A pretty minimally puny judgment, though. (A pet peeve: those critics – some in fairly reputable publications – who merely synopsize the plot of a movie or novel. Leaving some of us plebeians, at the end, frustratedly wondering whether they thought it was any good or not.)

How easy to shade a description so that an opinion is expressed, though:

With “The face is constructed of a tangle of highly orchestrated thick and thin calligraphic brush marks,” Panter’s “highly orchestrated” and “calligraphic” indicate the “thick and thin … brush marks” come from a skilled, thinking artist.

If “the alleged thief was seen skulking close to the jewel-case,” how more sinister was the action! Even “broken glass glitteringly spread across the street” adds some beauty to litter which is a dangerous nuisance…

————————

“Can it, for example, allow us to determine which of the three images above is of the most lasting value without recourse to something less than objective?”

I don’t think it makes any sense at all to judge these three images by the criteria of “the most lasting value” since they have different functions: a comics panel, a movie still and a painting. The painting is meant to be viewed as a single image, the movie still and panel are part of a larger work.

————————

But the Kirby is a splash page: much more to be read as a single, isolated static moment, rather than part of a sequence. (As were many other Kirby splash pages which simply featured big ol’ “talking heads.”) And the image from “The Scream” is a detail of the entire painting, which misses a great deal from loss of context.

Not to mention the Kirby panel also features words spoken, an expressively rendered title, the explanatory caption-box at top, with more narrative substance than some modern short stories. Though Ng asserts that “comics are more than mere pictures,” and that “[Kirby’s] stories could never be considered innovative in form by the measure of all narrative art,” interesting how Panter’s praise and other comments here ignore the writerly aspect of the work. Which adds a huge amount of context, which with other factors in my estimation bumps it up above the “scene from Lon Chaney’s Phantom of the Opera” and “low-res detail from Munch’s The Scream” for total aesthetic worth.

Mike: Just to be clear, that statement concerning Panter’s article was not a personal evaluation, but put forward in view of the high praise it has received in several quarters of the internet. That said, I do think it has some useful insights.

Hey Caro,

Isn’t Theory more appropriately used to refer to the usage of certain post-post-war philosophers (and psychoanalysis) in the service of analyzing stuff outside of philosophy proper, where the philosophical theorizing is more important than the stuff? Derrida isn’t a Theorist, but a philosopher. American lit-crits who consider themselves Derrideans are Theorists.

Hey Charles — it’s a little slipperier than that, at least in my experience. Think about what you would study in a “theory” seminar. You’d read the philosophers, not the secondary sources that use them. And you’d talk about ways to apply them to theoretically informed criticism. But in my experience you don’t read the applied work in those true “theory” classes — that work is your secondary material for the actual literature seminars.

So when you study theory, you aren’t studying literary critics who use Continental philosophy; you’re studying the insights and frameworks of continental philosophy that those critics use.

To be honest, I don’t recall hearing the word “theorist” used very often. Theory was the thing, not the practitioners. I think it is used to refer to Continental philosophy read in the interdisciplinary context, but it still designates the philosophy itself.

Also, remember that philosophers, especially in the US, tend to disown Derrida and the like. You’d get into some trouble calling Derrida and Lacan “philosophers” in a heavily Analytic department. Those people would probably call them “critical theorists” (which is term used for the German Frankfurt school: http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/critical-theory/)

I’m sure that’s the source of the term “theory,” but “critical theory” has such strong Marxist and sociological overtones it’s just not really appropriate for the poststructuralists and the psychoanalysts.

Caro:

“But your semantic arguments are pointless unless you actually acknowledge they’re about semantics. You want it called something else, say what you want it called instead. But you’re just not powerful enough to single-handedly change what it means in academia by fiat, nor to render the concept of professional jargon non-operative. Sorry.”

It’s not about power, Caro. You seem unable to understand that. If it were, your little coterie of academics’ microminority usage would be swept away by the sheer tsunami of everyday English usage.

Really, you are defending a bit of obscure, cultish jargon as depressingly autistic as a Scientologist’s appropriation of the adjective ‘clear’.

And, as I’ve pointed out– your peculiar use of ‘theory’ has no currency in French academic discourse.

I understand that you have “invested” enormously– in every sense of the word– in the worth of Theory (no article, capital initial, as you like)– but it’s an investment that, seen from without, seems scarcely worth the candle.

Alex, since we’re talking in English, it’s unclear what difference it makes what the things are called in French. If you want to explain what the distinctions are in French, and how the different groups are broken down, that would be helpful and interesting. Though since you’re not actually interested in the distinctions, it’s not entirely clear to me that you’d necessarily be the one to ask…but be that as it may.

She’s using a technical term in a technical way. You don’t like the group that uses the technical term. Okay. But the group is still there; they use the term the way they use it. Whether it’s worthless or worth something is a point to be argued on the merits, not on whether or not you like the way the terms are or are not used.

The point originally was that you’re accusing theory (or what you will) of being something that it isn’t. You refuse to name your adversary,and are thus in the odd position of attacking your own ability to define what it is you even think you’re talking about.

I mean…I actually don’t know what it is you think you’re talking about. I’m presuming you don’t like Derrida and Lacan and poststructuralists and/or post-Freudians and/or post-Marxists, but that’s really just an educated guess. You want critics who will privilege the text, right? You want humanistic readings? Or are you against evaluative readings in general (which I think would include a lot of humanist criticism) and want the formalist criticism Jeet is talking about?

Like I said, Alex, for I think the third time, if you want me to use another word for the Thing-I-Am-Talking-About besides the shorthand academics use (“theory”), then tell me what word you think I should use.

I vote for aardvark.

Either that or Nyarlathhotep.

Mike Hunter, can you please email me?

[my full name as one word] [at] gmail.com

by which I mean my actual name, as seen above, not myfullnameasoneword…

Sorry to hijack this thread, but since the TCJMB closed down I don’t know how to contact Mike.

I’d comment on the subject at hand, too, but I dreadfully dread getting into another tangle with Caro… :)

Noah, Caro– it’s not just a question of terminology. It’s trying to impose the perceived existence of something non-existent simply by an agressive appropriation of names. That’s why I compared the use of ‘theory’ by that lot to the jargon of Scientologists.

‘Theory’ doesn’t exist as a discipline. ‘Theories’ do exist. The theory of the leisure class, the theory of evolution, quantum theory, music theory, etc, etc.

Caro’s definition of ‘theory’ as being Continental philosophy post–WWII is so vague as to be positively gaseous. And, as I’ve pointed out, this only works by excluding rafts of philosophers, including giants such as Sartre, or recent guys like Bernard Henri-Lévy and Alain Finkelkraut.

Really, “theory” is a hodge-podge of numerous approaches awkwardly cobbled together into an ideology.

Noah, if I refer to French it is for 2 reasons:

1) because the fountainheads of Caro’s ‘theory’ are overwhelmingly French or Francophone. Derrida, Barthes, Foucault, Lacan, De Beauvoir, Irigaray… the list stretches on and on. And yet, ironically, nowhere do you find in French academia this usage of ‘theory’ to denote a discipline on a par with, say, ‘ethics’ or ‘ontology’. Academia is supposed to be cosmopolitan; thus,usage in another tongue is certainly relevant.

2) Caro notes that I am discussing semantics; well, yes, that’s my field. The contrast with French is illuminating because the anglophone ‘theorists’ have effected a subtle semantic shift impossible in French or in most other European languages: they eliminated the article.

Thus ‘a theory’ or ‘the theory’ becomes ‘theory’. A countable noun– by its nature as such limited in scope– becomes an uncountable noun, spreading out through the cosmos!

So in English, one can say “If we apply theory to…” with ‘theory’ understood as a universal, like ‘metaphysics’. In French, the same phrase gives us: “Si nous appliquons la théorie à…”– and invites the immediate question: which theory?

Noah: of the list you cited I have a strong aversion only to Lacan. To my mind, a dangerous charlatan. remember that he was a psychiatrist, with a following of hundreds in the psychiatric community. He was harmful.

I admit the thought of being treated by a Lacanian is pretty terrifying. However, there’s little evidence that any therapeutic method is better or worse than any other. That’s why Freudianism is still around. Check out John Horgan’s The Undiscovered Mind. He suggests basically that therapeutic success is all due to placebo effect. In any case, there’s no scientific evidence for arguing that Lacanian therapy is particularly harmful, I don’t think. (Jones may show up and refute me, though.)

That’s a much more helpful response on theory. Thanks.

Does this include psychiatric medication? Just curious about the book.

It pretty much does include psychiatric drugs…which I have trouble believing. He’s pretty convincing though….

His basic thesis is that we don’t know how mind works and are very unlikely to ever figure it out. Certainly he feels we have made little or no progress.

It’s a really good book, I think.

Alex: If you want it qualified to say “in the American academy, ‘theory’ refers to Continental Philosophy since WWII as understood in the interdisciplinary context”, fine, but I’m not going to type that every time I say it. I’m going to use the shorthand “theory” like everybody else in the American academy and point you back to this post. Since it was acknowledged as both jargon and shorthand, the context should have been obvious. But perhaps since your field is semantics you are incapable of intuitively grasping pragmatics.

That said, the grammatical incommensurability between French and English here is not relevant. Theory in the US academy is discussed in the context of praxis, pedagogy, and methodology, (and here at HU almost always in terms of methodology) and as our academic environment is quite different from the French one, our praxis will be different too.

You are just being factually incorrect and sloppy when you extrapolate from the fact that “theory” cannot be translated into French to the statement that it “doesn’t exist” in America. It is not a “discipline” (which is an institutional structure) but it is a field.

Here’s a book often used as a textbook for undergrads: http://www.amazon.com/Beginning-Theory-Introduction-Literary-Cultural/dp/0719062683

Your head will explode, I’m sure, at the title of the first section “Theory before ‘Theory'”.

It is not dissimilar from something like “women’s studies.” When I was last aware, in the ’90s, the term “women’s studies” wasn’t in currency in the French academy: it was still “Le féminisme” and it still lacked meaningful institutional recognition. The idea that academic institutional practice is international, that no language needs terms to refer to phenomena that only exist in the specific context is palpably ridiculous. (You might want to consider reading some Derrida on translation.)

One of the main reasons is that the disciplines don’t match up. For comparison, very few Universities in the United States have Departments of Semantics. It’s almost entirely a European discipline, as is Semiotics. Linguistics is the parent department for semantics, which was (at least in the ’90s) generally taught exclusively alongside pragmatics as companion approaches to the study of meaning. Semiotics, with a couple of notable exceptions at schools which were very involved in the linguistic turn here, is completely subsumed into theory, and is therefore studied and practiced only in interdisciplinary contexts.

And, as I pointed out previously, theory does not exclude Sartre. It CERTAINLY doesn’t exclude Levy who was at one time a student of Althusser; Barbarism with a Human Face was on the syllabus for the class in Marxist theory as one of the more significant critiques. Again, you seem to be misunderstanding this “thing.” Which shouldn’t surprise me since you keep maintaining it doesn’t exist.

Since usage determines denotation, I’ll have to accept the term as stated above, but I don’t have to like it.

I did not say that because it can’t be translated into French it doesn’t exist. As a bilingual from infancy, I know that’s ridiculous. French has no word for ‘mind’, either, but the concept is known and discussed.

The language I was discussing was English, and the French was cited in contrast. This dropping of the article has subtle (I was going to say sneaky) appropriative effects. One of which is, yes, suggesting it is a discipline rather than a field.

That academies’ don’t always “map” is true, though they do in the case of this field to a great degree.

Alex, how does the dropping of the article suggest it’s a discipline?

I’m not entirely sure I’m understanding the difference between discipline and field in your usage: I was using discipline there to refer to discrete institutional standing, which the article wouldn’t really effect (as it’s based on things like administrative positions, offering degrees, and exploiting TAs.)

Oh, I missed this: I don’t think the academies map in this field at all.

I think the study of theory in the United States would be immensely helped by the establishment of Departments of Semiotics, or at least Institutes of Semiotics. The rigor with which theory (any theory!) is studied, due to its full interdisciplinarity, is definitely lacking, and the biggest culprit behind this, I think, is the fact that although theory is grounded as much in linguistics and semiotics as classical philosophy, very few literature or “studies” majors study linguistics and semiotics except through secondary souces. I wasn’t even required to take an undergrad survey in linguistics or grammar. I did take grammar, ’cause I LOVE grammar, but it wasn’t REQUIRED. And I did independent studies in semiotics with European professors.

But the lack of institutional specificity for theory in the US academy makes its pedagogy very ad hoc, as I think that textbook shows.

The problem is that because there are no departments, there are no jobs, and because there are no jobs, there’s no need to specialize in it. Academia is very self-referential.

Well, they don’t map, but they overlap…we could do a nifty Venn diagram to illustrate this!