Part of the Eddie Campbell-The Years Have Pants Roundtable

This one’s too big to really get a good grasp of. It’s a wizened but lively old cat at 600 pages and 30 years long. You can hold it up by the scruff of its neck with the strength of one hand, but not for any reasonable duration.

Then again, you don’t really need to. There’s a summary provided by the author himself (and who else better to do it) — a pilgrimage to Hugo Pratt’s breakfast table during a comics festival in Sierre, Switzerland. The words are Pratt’s but they weren’t spoken to Campbell during that meeting. Instead, depending on your faith in the narrator, they were taken from an “older interview” with him where he recounts a kind of third person autobiography, which in turn describes everything that we have read up to that point.

“I once wrote a kind of an autobiography where I talked about people, and through them, about myself. Everyone said it was a wonderfully funny autobiography. Whereas I though I’d written a very sad book. Scary, in fact. It was the end of my youth, the evocation of people who have died, who have disappeared. No one noticed the poetic touches.”

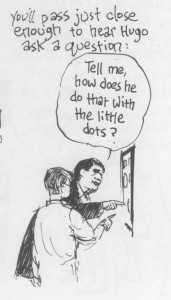

Campbell never finds out (or never records) why Pratt wanted to see him in the first place, but he does get an inkling of this mysterious inquiry when he walks past him at an exhibition, finding him deep in conversation with “The Man at the Crossroads” (Paul Gravett to everyone else). The query is uncomplicated — “Tell me, how does he do that with the little dots?” — and self-referential.

When that consummate practitioner of the brush asks about Campbell’s use of zip-a-tone, we find that he’s been shaded in exactly that fashion just four panels before; that avaricious, narcissistic ouroboros turning back on itself, referring us back to where it all began — the heady and impoverished years of The King Canute Crowd with its greater rigidity of form if not narrative, the mechanical tones offering up a symbol of that enterprise.

Not a moment of direct revelation, but a question asked in the third person, glancing off the surface of the issues like the images on the page; the gris-gris of self-analysis…

…the journey without destination.

People are going to say that it all starts rolling around here (page 200 of the bumper edition), in the pages of How to be an Artist, a personal history of the British Small Press with its pacts with silent Gods, and that man at the crossroads (he’s still there). The cartoonist is now weighed down with nearly 20 years of experience, and settling into a form and structure which anticipates his future direction (The Fate of the Artist and his aborted history of humor). But it’s less reckless; more sensitive to history and the many feet treading around him on that dance floor — filled with a surfeit of good sense. There’s a kind of abandon in the current brushwork wrought through years of practice on From Hell. Campbell’s hand has experienced a kind of liberation, the contemplation slightly less so (art mirroring life).

What I remember is that messiness; that episodic narrative and chronology peppered with drink and sex (all of which made Campbell’s Bacchus all too easy to understand): the “slumber parties” at the local pub; Danny Grey pissing into refrigerators and precious handbags; the persistent bouts of inebriation leading to nights out on the sides of motorways; the jokes; the strange goose taking a stroll behind the author; and a quaintly melancholic denouement.

All fading into indistinct memory now that twenty years have passed since I last read the “complete” Alec (1990). Like Montaigne and the “treachery and weakness” of his memory, I wish I had added notes to the end of each book to rouse my impressions from so many years ago. But the sensations are still there (or just about), and I can sense them on the surface of those early works even if I can’t feel them as acutely as I did once before; one of the absurdities of age, that insatiable yearning for a more primal sensation.

As with any conversation taking in a long involved history, I think the reader should feel free to nod off once in while as he takes in this book. It’s meandering yet crisp; revealing but,with time, much more guarded. One presumes it is maturity and respectability that have brought this about; perhaps the civilizing influence of a wife and children, as well as the business acumen that sometimes comes with that venture (which in this case was followed by the gradual exchange of boozing for bibliomania) .

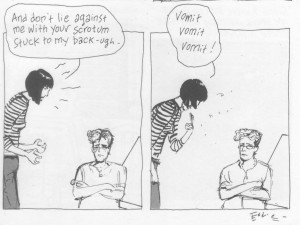

It’s all wine and roses for Campbell now apparently. Age and married life has had its rewards: a creaking front gate secured with a pair of underpants; tampons hurled on to the walls of his accommodation by his daughter, and the licence to lie against his wife with his scrotum stuck to her back.

Someone should tell Campbell that he’s allowed to make a few things up after 27 years of marriage. Maybe he did.

Later on this week: Much better things…love, hate, and anger.

Has cambell been notified about this roundtable? he commented a while back on a Domingos column…it would be cool to have him comment on these articles… as they’re already written, as I understand it, it’ll not be intimidating…

Campbell knows about it.