A new crop of comics artists are merging their craft with the journalistic process to create stunning works of reportage that depict everything from war torn countries to wineries. They work in ink, watercolors, and Wacom, telling stories that might not make the front page, but offer a level of nuance and meditative depth often reserved for the best investigative reporting. They are “graphic journalists,” and their work is a little-known facet of the infographic revolution that is sweeping the journalism world.

In two weeks, I’ll be at the National Conference for Media Reform in Boston, presenting on the role that comics play in the future of journalism as part of a panel I’m co-organizing with Sarah Jaffe. Since HU is dedicated to comics analysis and scholarship, I’d like to give you all a sneak peak at the ideas we’ll be grappling with. I’d also like to give a special thanks to Sarah, Susie Cagle, and Matt Bors for working with me to develop our working criteria for graphic journalism.

What is it?

Graphic journalism is an emerging form with a colorful mishmash of influences that include comix, infographics, film, and autobiography. There are multiple ways to categorize and analyze this work. From AlterNet to the Awl; The Rumpus to the Oregonian, graphic journalism offers a powerful opportunity for news organizations to reach out to new readers and experiment with new ways of storytelling without compromising journalistic integrity.

Here’s a short overview of the different forms that comics journalism can take. As this is an emerging field that we’re working to define and develop, I’d love to hear your recommendations and thoughts in the comments.

Travelogues

Since the underground comix revolution of the 1970s, comics have been used as an autobiographical medium. The late Harvey Pekar used comics to tell the stories of everyday people and everyday life in an accessible manner. Today’s travelogues are direct descendants of early diary comics. These works are often meditative explorations of a foreign landscape in which the reader unpacks their cultural baggage with the author, exploring a strange land with them. The key here is in viewer identification: The comics creator has a strong voice leading the narrative, and we trust them to impart facts and dissect stereotypes for us.

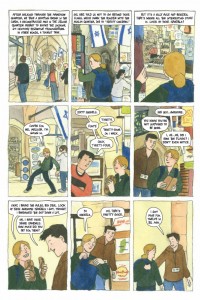

Sarah Glidden’s How to Understand Israel in 60 Days or Less is a near flawless example of the travelogue. Glidden isn’t going for an objective non-fiction work here, which can seem counter-intuitive to journalists. Rather, she’s looking to use her experiences as a lens for dissecting her own cultural (mis)perceptions and takes the reader along for the ride.

At Cartoon Movement, Matt Bors is publishing pages from his experiences in Afghanistan last summer. While the narrative has yet to fully unfold, so far Matt is taking a more ethnographic/documentary approach, focusing less on how the travel impacted him and more on documenting the landscape around him.

Portraits

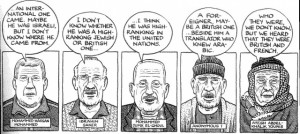

The portrait style of grpahic journalism is even more immersive than travelogues, though the two forms often overlap. In a portrait comic, the creator steps back and lets the facts or individuals speak for themselves. Joe Sacco, a pioneering graphic journalist, often lets his subjects tell their stories, letting their words tumble out around portraits of his subjects speaking. By focusing in on facial expressions, the reader is effectively looking over Sacco’s shoulder and engaging in a dialog with the subject. The same principles apply to an “over the shoulder” style of interviewing common in documentary films and video journalism. By removing the interviewer from the panel, Sacco is able to increase the readers identification with the subject at hand.

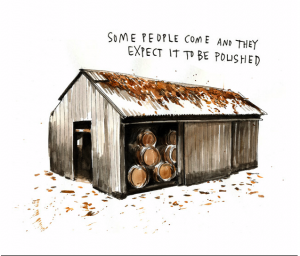

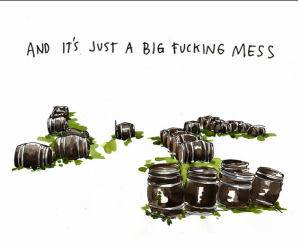

There are many ways to increase identification via portraiture. While Sacco tends to focus on faces, Wendy MacNaughton takes a much more experimental approach in her works for The Rumpus. Through her innovative use of white/negative space, MacNaughton presents comics that are free of an overbearing narrative presence. She often pairs words with snapshots of objects and landscapes to create an experiential identification with her subjects. In MacNaughton’s work, the reader is encouraged to focus on and identify with the forms on the page, absorbing the places and things that pepper her subjects lives as a meditation. This approach encourages internal identification from the reader. Instead of presenting her subjects as an interview, she wants us to experience life through their eyes.

Choosing Your Own Adventures

While Susie Cagle creates great non-fiction narrative work, she also experiments with how to make infographics more interactive by introducing comics techniques. Here’s a short “choose your own adventure” comicgraphic that Susie did for the SF Public Press. When I interviewed Susie a few months ago for a separate article, she said that infographics and comics have “got a lot of the same things going for them. … [But] my problem with comics journalism is that most comics journalists come to it from an art school background and the writing and research isn’t there.” Infographics and expository illustrations like the image below are helping fill that gap.

Merging Multimedia

Dan Archer has been experimenting with integrating comics and journalism for years. As a Knight Journalism Fellow at Stanford, Dan is creating annotated comics that source back to videos, audio, and other data that supports his reporting. Readers experience journalistic stories as digital, interactive landscapes. Each click of the mouse–or swipe of the finger–allows the reader to dive further into Archer’s reported world. Archer and developer Chris DeLeon recently released an iPhone app comic on the Honduras Coup.

What’s next?

This is just a short overview of a few archetypes I’ve been able to identify in the last few months of studying graphic journalism. These definitions are sure to evolve as additional organizations and journalists begin to experiment with illustrated narratives as a means for telling stories and creating experimental works of journalism. I’m looking forward to identifying new artists and connecting the dots as the field moves forward.

Not sure how much you want to go into this Erin, but…one of the things I wonder about journalism like Sacco’s is what the pictures add. Do you really feel that there’s an important element of identification there? It seems like you could get a very similar experience with just text…and just text is cheaper, which seems relevant if the point is to get the word out….

David Lasky told me once that, when he did comics-based reporting for a college paper, the people in the room virtually ignored him at student government meetings- he didn’t have a microphone, or a camera. But that after the first one was printed, and they actually saw the things they had said emanating from representations of themselves, that it changed the way they conducted business in the counsel room. They were a lot more reserved, more careful about it. David was of the opinion that the immediacy of a comic is radically different from a transcript, and that the immediacy made that kind of reporting accessible to a different kind of audience. Not to put too many words in his mouth, but interesting points…

Seems like fumetti would be more efficacious. Paste some balloons on some photos…

Eric: Thanks for the link to that MacNaughton piece. It’s really lovely and evocative in a way that text or photos would not.

Sean, love that story. A lot of the comics journalists I’ve talked to deal with that attitude–and a lot of publications don’t know what to do with journalistic comics, even online. But as the journalism industry struggles, I think there’s a lot to be said for experimenting with new ways of telling stories.

But, going back to Noah’s comment, I think that identification and reader immersion are key. Comics can address really awful things in a palatable manner. Sacco’s use of headshots and portraits allow us to fundamentally connect with individuals who have been through very hard times. Palestine has some particularly beautiful narrative pages that really humanize an awful situation, just because you’re looking at a person narrating their experiences.

Derik-

Then you’re back to being a reporter that people perceive as such. A person in front of a camera acts in a different manner than a person sitting in the room with a quiet man doodling in a notebook.

I’m interested personally in the question of whether comics reporting can ever truly be objective. I’d suspect that most frequent commentators on this site believe that no reporting is ever really neutral, but it definitely adds another layer of judgment to draw/caricature the people involved in a situation. Although, perhaps because the reader can see this kind of characterization and spin very easily, it matters less…

Just to be the grinch, I guess…I also wonder whether humanizing is really an ideal goal for journalism in general. Who benefits from increased empathy exactly (presuming increased empathy is the goal)?

That’s a question I have about investigative journalism in general, but it seems like it might even be more pointed for some graphic journalism….

Oh, and Derik, Erin’s name is Erin, not Eric….

I almost did the same thing when I wrote my twitter blurb; had to erase the first try. Stupid fingers….

Sean, count me in the camp of those who believe that journalism is never truly objective. I think the best way to counter that is, in fact, by making it clear who the filter is, embracing the bias, and graphic journalism does that in a beautiful way.

Noah, increased empathy is not really my goal. My goal is more eyeballs; making information more palatable to new audiences. Who benefits from increased empathy? Well, journalists I guess. We use individuals to represent larger issues across all mediums, because readers don’t want to sift through spreadsheets of data. Still, I can’t think of any reason why getting people to care is really a bad thing.

Well…empathy can be leveraged in various ways which are arguably bad. Empathy for the victims of the 9/11 attacks ended up generating the political will for a couple of wars, various human rights abuses, etc. The war in Libya is a war of empathy, and that may very well have really unfortunate consequences.

I think in general the world would be better off with less of our empathy and more of our absence.

I second Susie’s point about accessibility to mountains of information or unglamorous but important news stories vying for the attention of the ADD-addled online reader. But I disagree with Noah’s point about empathy being a bad thing across the board. To me, it’s key to showing the reader that the key to understanding an issue lies just as much in the micro (real voices, human perspectives and the empathy generated for those involved), as the macro (statistics, official reports, etc). I think Sacco does the same thing in his work – breaking down the grand narratives of the bosnian war or the conflict in the middle-east into the fragmented, individual voices of their victims whose suffering constitute the bedrock of (and human interest in) those stories. Frankly, the worst thing we could do as an educated, well-informed readership is take pride in our apathy. There’s a gulf between generating empathy and forging a need for retribution.

I think comics journalism functions best as a sort of feature writing, where a balanced subjectivity is assumed.

Erin, good piece. Here in France comics journalism is vigorous and plentiful, and I’ll be posting about it next month.

Anf Noah, your misanthropy is showing! Tsk!

A healthy does of misanthropy is a good antidote to the inevitable cruelties of optimism.

Dan…it’s easy to say that there’s a clear line between empathy and imperialism. The fact remains, though, that from Kipling on down, imperial adventures have always been justified through the claim that we’re helping others.

Empathy becomes part of an ideology of control; you think you understand other people and so have a right/duty to adjust their lives for them.

But that’s not true empathy– it’s an illusion of empathy.

Right; you’re claiming it’s a bug, not a feature. Which is what people always claim. And then we go and bomb someone else in the name of empathy.

Another example of comics-as-journalism might be Emmanuel Guibert and Didier Lefèvre’s The Photographer, which used comics to provide a narrative context for the photographer’s work. The book didn’t integrate the photographs and the comics as well as it could have–it was also trying to be a comprehensive album of Lefèvre’s work in Afghanistan, and went about it in some ill-considered ways–but it was pretty impressive nevertheless.

This discussion of empathy eerily echoes the debate at the confirmation hearings of Justice Sotomayor…

Sean: “Then you’re back to being a reporter that people perceive as such. A person in front of a camera acts in a different manner than a person sitting in the room with a quiet man doodling in a notebook.”

But with camera phones and the like, aren’t we always in front of a camera. One can be pretty discrete with cameras.

I think graphic journalism, does allow for a greater manipulation of events than photojournalism would (not to say photos aren’t manipulated). But on the other hand, I’d imagine most people will take drawings of events less literally than photos.

Noah/Erin: Sorry, I meant Erin (I even looked at the byline to make sure), that was just a typo…

I was talking about identification, not empathy–though I don’t disagree with the utility of empathy in graphic journalism.

There’s a crucial difference: empathy implies pity for a person in a situation; identification is more akin to in-depth comprehension. In my mind, graphic journalism serves a similar role as deeply investigative reporting. It untangles and unboxes complicated concepts so that they are easier to navigate and comprehend. And ease of comprehension is key to increasing understanding and engagement with content.

I think empathy is often used in the sense of comprehension…and in any case journalism often seems intended to evoke pity….

So the point of graphic journalism is simplifying? Charles Hatfield would not be pleased….(his book Alternative Comics argues strongly against the idea that comics are an inherently simpler form than writing….)

Not simplifying–making accessible. Big Difference.

And, of course, not all stories are easy to read. I’m saying that graphic journalism provides a better, clearer entry into complicated issues and reporting. Think about some of the reporting on the financial crisis–without smart visualization, a lot of that data would have been lost on even the most astute news consumer. Or, alternatively, think about the graphic adaptation of the 9/11 report, which visualized hundreds of pages of dense text. It didn’t simplify, but rather added smart visual context, which helps the reader connect the dots faster.

The key here is providing readers with a key to unlocking data. I’m not saying everyone shouldn’t be able to do the work and read a long text article. I love long form journalism. But I do think graphic journalism makes it possible for more people to engage in a nuanced conversation.

Just wanted to throw Guy Delisle into the conversation. His books vary as to the amount of reportage versus memoir, but I found Pyongyang, his chronicle of his time in North Korea’s show capitol, incredibly rich and rewarding. Very “surface”, but still very rich in implication (and virtually impossible to replicate through film and photography, due to restrictions by the government. Although there have been exceptions granted, like the BBC documentary re: the annual games ceremony)

I’m glad that this conversation is happening. As someone who is only now wading into the world of journalism comics (and I mean, I dont think my first book was journalism, it was memoir/travelogue and I’m glad that Erin makes that distinction in this piece) I find myself facing a lot of choices that are hard to navigate because there are not yet specific journalistic standards for comics that I know of. The standards for print journalism and documentary are pretty straightforward. But with comics its still fuzzy.

I do think all journalism is subjective in one way or another, but its true that comics add another level to this. Clearly I’m pro journo-comics (otherwise why would I be making them?) but I feel like there needs to be some sort of agreed upon set of standards set up by the creators and these are important things to think about.

I don’t want to get too far into how-your-journalism-sausage-is-made, but I don’t think the standards governing print and broadcast are as strict as we might think they are or like them to be (and I don’t think that drawing as a medium is inherently any less true than photography, which can also be manipulated in any number of ways). Quotes are routinely spliced together, “shaped” to fit the narrative, taken out of context and reordered by the top writers at the top publications and programs — to me, this is as subjective as the way someone’s facial expression is rendered in a comic. Editing is necessary; we can’t show everything, and there will always be a human hand involved. But there is a presumed level of trust with print and broadcast reporters — that they aren’t lying to or misleading us, that they are seeking the truth, more or less — that I think graphic journalists should be able to earn as well.

Well, it’s interesting to consider that, as I suggested before, maybe the biases inherent in a drawing are just so naked and obvious that someone is unlikely to attempt to use those biases in a tricky way. Maybe I’m naive in this, but the editorial control someone has with a comics page is just as great as with prose, and with film- the areas of potential manipulation just fall into different arenas. So if you’re left with, essentially, how you draw/depict/stylize people and events as the primarily new way a graphic journalist can spin something, maybe that’s okay with me. After all, if Sacco had depicted all of the Israeli soldiers a certain way and all of the Palestinians with another slant, that would be pretty obvious to the viewer (unlike, say, sketches and paintings coming back from the New World in the 1400s, when the idea of an entirely new continent was so fanciful and individually unverifiable that any graphic slander committed upon the people living there could be accepted in good faith). Actually, that might be interesting to take up at some point- if there’s a connection with modern comics and graphic reporting, and the map making and reportage done my the European explorers in the New World….

Cross posts :)

This discussion is, I believe, actually about someting larger than comics journalism__ it’s about non-fiction comics; a vast, VAST subject that has received practically no study– HU can help correct that!

Personally, I think the non-fiction form comics are best suited to express is the essay– see Crumb’s “Where has it gone, the Beautiful music of our Grandparents?” for a superb example; or Harvey Pekar (with Val Mayerick) on “Violence”.

Glad to see people talking about comics and journalism in the same breath. Also glad to see people I admire and respect (Susie, Dan, Sarah esp.) getting involved.

On questions of objectivity: Personally I think all journalists benefit from having humility and being honest about their own take on any given story. I love the Kim Deitch story “Ready to Die!” because you can see on his face how completely uncomfortable he is. For me, what’s truly excellent about doing journalism in comics is having people relate to your reporting at the level they relate to fiction comics. I think that if I’ve done my job and it’s real journalism, then this passion—this empathy—is probably a great thing.

Also, Sarah: I agree, let’s make those standards! It wouldn’t hurt to talk it out a bit. I’m trying to do that a little here: http://www.cartoonpicayune.com/?page_id=2

Pingback: Monday Tally: Graphic Journalism and Moby-Duck

Pingback: A Refuge for Graphic Journalism « Nonfiction Comics

Pingback: Graphic Journalism | JoanHilty.net

Pingback: Comics Journalism Reading List | Kenan'?n Akademik Penceresi

Pingback: Graphic Journalism: Insightful or Subjective? | Journalisticampus

Pingback: Drawing a crisis: how journalists are illustrating the plight of refugees | chloe d'costa