Welcome to “Can The Subaltern Draw?,” a new monthly column by Nadim Damluji that will explore what comics look like in the in-between space of cultures. Two things: Column title should be pronounced with tongue in your cheek and the author really agrees with Anne McClintock, especially when she writes: “I believe that it can be safely said that no social category should remain invisible with respect to an analysis of empire.”

One of the main reasons I embarked on a year of comics-related travel was to find historical proof that non-Western alternatives to Tintin existed. One of the stops in this journey was Egypt, where I was looking specifically for a regional comic book hero that children from all over the Middle East idolized, learned from, and escaped through. Where was the Syrian version of Astro Boy hiding? Why doesn’t the Arab World have a Superman?

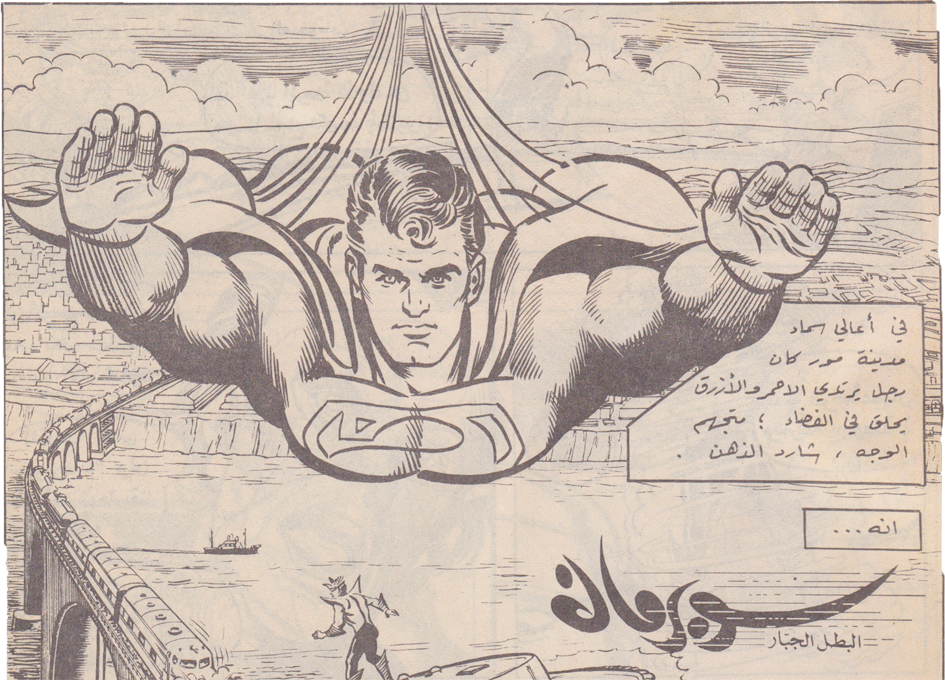

In 1964, an editor at Lebanese publisher Illustrated Publications (IP) seemingly answered this very question in the form of mild-mannered Nabil Fawzi. As catalogued in an excellent 1970 article from ARAMCO Magazine, IP reasoned the Middle East contained a potentially viable market for the same adventure comics that had become popular (and profitable) in the United States; comics like The Adventures of Superman. But instead of creating a Superman-like hero for an Arab audience, IP decided to teach the man of steel himself how to speak Arabic through translating the already abundant English editions of the comic. With these translations we bear witness to the the birth of Nabil Fawzi:

“The first comic strip to be issued in Arabic by IP was Superman. In the guise of Nabil Fawzi, a reporter for ‘Al-Kawkab Al Yawmi’ he swooped into the Middle East from distant Krypton on February 4, 1964, to the instantaneous delight of thousands of young Arab children.”

Translation: Superman IS Nabil Fawzi

Translation: Superman IS Nabil Fawzi

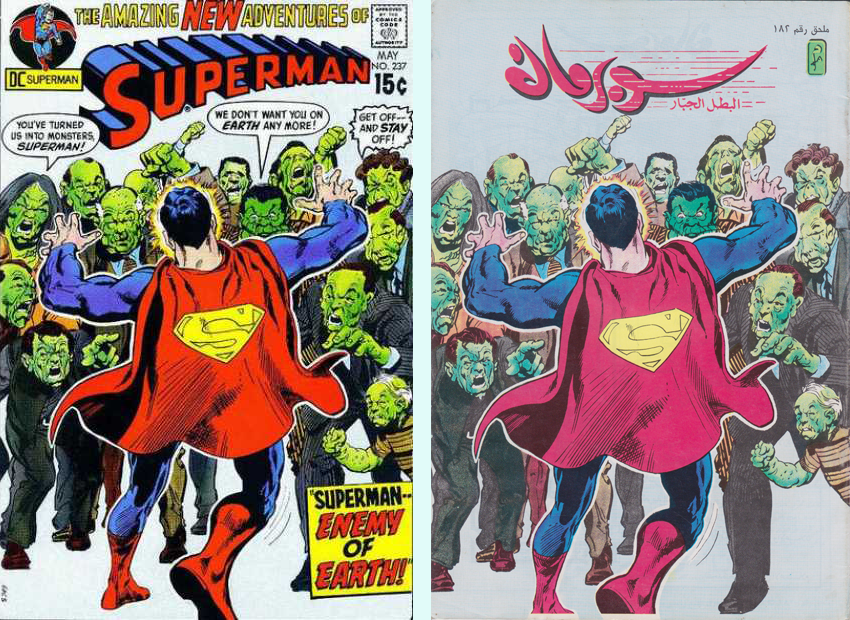

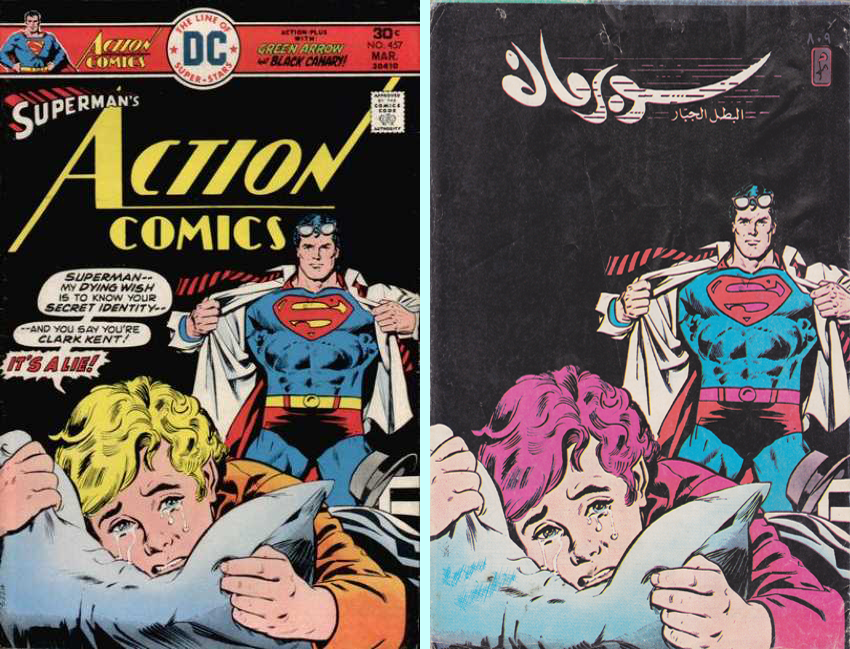

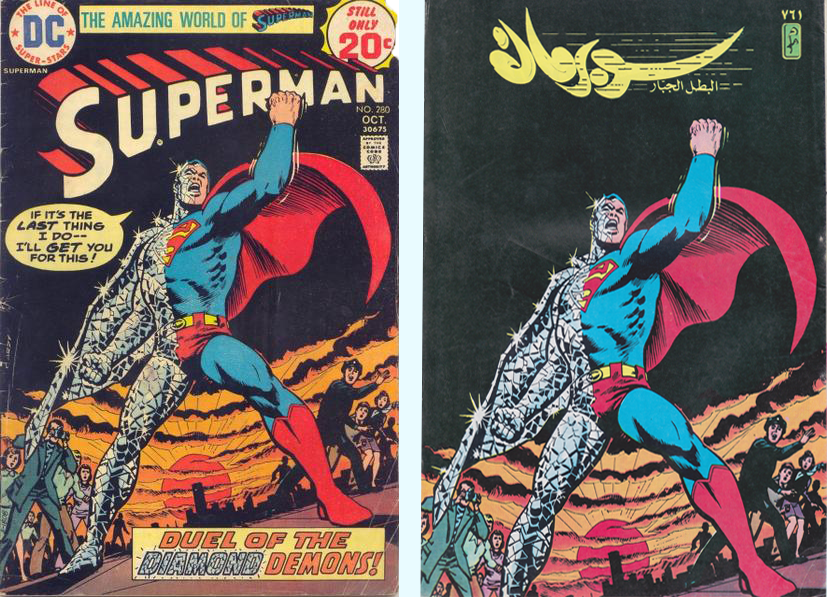

Indeed, while it has been exciting to find plenty editions of the Arabic Superman (technically pronounced “Suberman”) in my Egyptian book market excursions, it is very weird to see the well known hero recast with the name Nabil in a presumably Arab Metropolis. I say “weird” because all that has changed is the name. Essentially a big eraser was taken to the English text and the editors at Illustrated Publications (after convincing Western publishers to license the material) retold the story of arguably the most famous American superhero to a captivated Arab audience. In order to give you a sense of what exactly these alterations look like, I’ll pause here for a bit of show and tell. First let’s look at how some covers changed:

English covers via the archive at Cover Browser.

English covers via the archive at Cover Browser.

Before I found their English counterparts, I was confounded by these Arabic covers. As you can see, the most noticeable difference is that most of the text — sometimes known as “context” — is removed. I found both scenes so confusing that my best guesses were up top the artists were depicting a Zombie invasion and below they were illustrating that one time Nabil mistook a weeping child’s room for a phone booth. Another noticeable difference is the color palette, which takes on a different shade in the Arabic versions. The blond crying boy turns into a red head, and Superman’s signature “S” gets a less iconic red and pink treatment. Beyond the covers, the “S” on the chest represents the most glaring difference throughout the Arabic translations:

Since Arabic moves right to left, the “S” was inverted along with the rest of the art before being translated. For me that backwards “S” serves as a visual cue throughout the entire translated series of how misplaced “Nabil” is in his Arabic surroundings. In fact, I find the whole translation of Superman to be a somewhat problematic venture, insomuch as it deferred the creation of a uniquely Arab superhero in favor of re-presenting a clearly American icon. You can change his name, place of employment, and hair color hue, but at the end of the day Nabil Fawzi still looks like American-bred Clark Kent. This new idol for Arab children — and a lot of them considering IP publishing 2,600,000 translated copies annually — was identical to the long established idol of American children: a superhero living in a big Chicago-like city but raised and moralized on a small Kansas farm. Ultimately, the name “Nabil Fawzi” does as good a job at disguising this true identity as Clark Kent’s glasses do at obscuring his identity as Superman.

Back in 1964 (especially in 1964), other Arabs shared this concern. As the ARAMCO article recounts, there was a real objection to importing a Western product instead of generating a new superhero out of the rich Arab history and artistic talent. Unfortunately, the article brings up this criticism as steadily as it dismisses it as “impractical” based on the testimony of Leila Shaheen da Cruz, then publisher of Illustrated Publications. As she states in 1970 on the reality of creating an Arab superhero instead of translating an American one:

“That kind of art work, story continuity and long-range planning, is still unfamiliar to most local artists or is too expensive. The adventures of Sinbad, the Sailor, for example, would be a natural out here, and we know that there would be a rich market for an adventure strip based on the exploits of Arab commandos. But so far we haven’t found a local cartoonist who is not either inexperienced or overpriced.”

The main reason I contest Mrs. da Cruz’s assessment is because I have in my possession Arab comics dating back to the 1950s which refute her claim that local cartoonists were “inexperienced,” and bearing in mind the original retail value of these issues I doubt their talent was “overpriced” either. Indeed, creating Nabil may have been a good business decision, but it is deeply unfair to claim that a profitable business choice was creating a cultural product that Arabs could not.

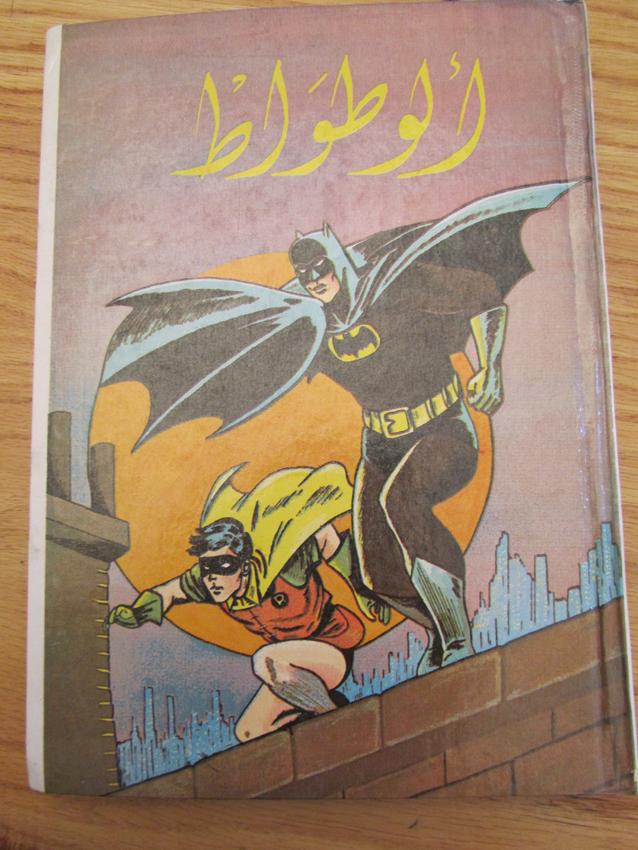

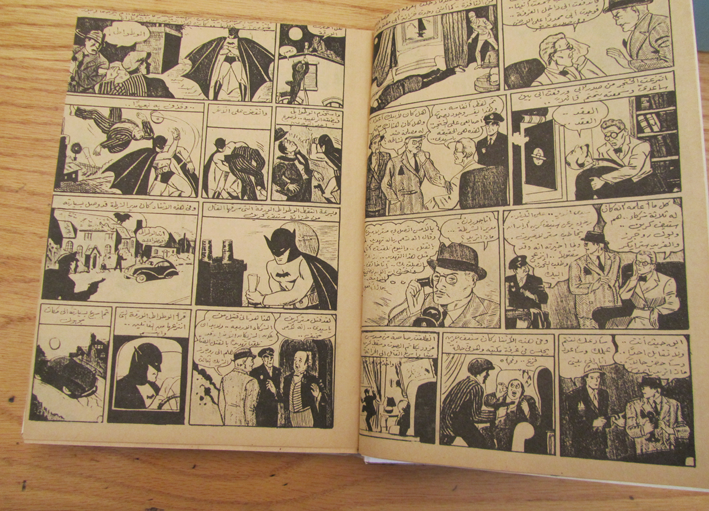

Now for a moment of contrapuntality: I don’t think that translating Superman was a completely deplorable endeavor. For one, his success ushered in a string of other well-known comic book heros. Superman was soon followed by Arabic versions of Batman and Robin (renamed “Sobhi and Zakhour”), Little Lulu, Tarzan, and The Flash. These are comics that I grew up reading in Lebanon, and I concede that on some level a child escaping through comics is a child escaping through comics no matter where that child happens to read them.

In retrospect, Superman’s presence in the Middle East served as an integral chapter in the history of Arab Comics as a whole. One can argue that without Nabil Fawzi fighting evil from the 60s onwards, we wouldn’t have many of the talented regional artists we have creating comics today. In fact, many of the generations who read Nabil as kids later grew up to challenge his faux-Arabness. Take for example The 99, an extremely popular Arab superhero comic created by Dr. Naif Al-Mutawa. These comics feature the same tropes found in issues of Superman, with the chief difference being they are actually Muslim heros (with powers based on the 99 attributes of Allah) for a new generation of children to look up to. Bringing it full circle in a way, a recent crossover event featured members of The 99 fighting crime alongside DC’s Justice League (of which Superman holds a membership card). In an interview I conducted with Dr. Al-Mutawa in Abu Dhabi, he explained that The 99 was created precisely to form new positive associations with Islam among children globally. Just as Superman was being Arabized in the 1960s, today The 99 is being translated for an English speaking audience. Encouragingly, this time around characters like Dr. Ramzi aren’t being recast as Dr. John in translation.

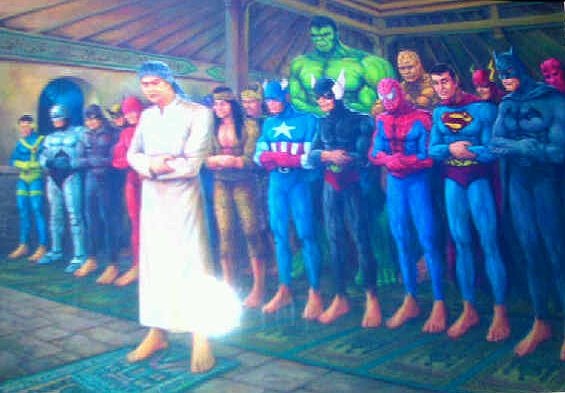

I’ll leave you with a subversive contemporary take on Nabil Fawzi and his famous friends that was recently spotted in Indonesia — the country with the highest population of Muslims — and subsequently made the blog rounds. Isn’t it strange to see Mr. Fawzi putting his actions where his name is?

—–

Another link to that indispensable ARAMCO Article that this post heavily relies on is here. I also highly recommend checking out these scans of the same article that some kind soul put on the web. Those certainly are some wonderful accompanying graphics.

Speaking of, here is one more cover comparison that I didn’t want to clunk up the body with:

Nadim, I notice that on the translated covers, it still says ‘suberman’, forgive me if I missed something, but is Nabil Fawzi then the Arab Clark Kent and Superman remains Superman? Was this a legal thing or a free decision? Seems interesting.

I’m massively interested in whether you feel all of this made a difference to your reading of the comics as a child, I mean, were you aware when reading that these were foreign stories with foreign characters, or did you just fit them into what you knew and see aspects of Lebanese culture in what you were reading?

I mean, I just wonder how true it is that Nabil Fawzi was the same idol to Arab children that Superman was to American kids, isn’t there some way in which the readings of the comic differed? Great article though!

Those covers are great! I love the sparse design and the logo. Interesting how streamlined and graphic they seem compared to their cluttered American counterparts.

@Ben Thanks for your comment! If you read that article I link to you get the sense that it was a free decision (since the legal rights had been secured) to keep the name “Superman.” Maybe it was because of the global name recognition they didn’t translate “Superman” while still changing Clark to Nabil. Then again, as I state later, Batman and Robin became “Sobhi and Zakhour.” It is curious.

As for my personal experience, the distinctions weren’t so clear cut for me because I grew up mainly in the US and only partly in Lebanon. I remember Superman movies, TV, and comics from the States well before I had any Arabic editions (which by then were mostly out of print). It is hard to access the slice of people I am directing my point about idolization at because they were children comics fans from the Middle East in 1964. I am, ahem, quite a bit younger than that, so I can’t really speak to what the experience must have been like to confront Nabil with Clark later on for that generation. Basically, since it’s near impossible to fully understand the particular lenses through which the Arab versions were read, the best I can do it criticize the way in which the product was made and presented.

@Sean You betcha. I certainly plan on framing a couple of issues when I make it back to the US.

Hmm…to those with dirty minds (count me, alas, in their number), that Arabic version of an Action Comics cover where Superman undresses, behind a weeping boy…ahem.

Nadim, this is interesting as a general tendency in Arabic- language comics to adapt superficially to the culture, creating faux Supermen and Mickey Mice. Was this standard practice?

I’ve seen the same phenomenon at work in American and British kid’s literature transposed into French. For example, the American girl detective Nancy Drew becomes the French Alice in translation…

Works the other way, too.

As you know, Tintin has been thoroughly internationalised, to the point of blandness. Much the same could be said about the Disney crew…and when Steven Spielberg was solicited to adapt the Harry Potter books, he would assent only if the books’ kids were made American.

Brrr! Dodged a bullet, there.

And you can add some art credits.

1) Curt Swan and Murphy Anderson

2) Neal Adams

3) Ernie Chan and Dick Giordano

4) Curt Swan and Bob Oksner

5) Carmine Infantino and Murphy Anderson

6) Bob Kane

7) unknown muralist

8) Nick Cardy

“And if you listen, you can hear

A mumbling sound in your ear,

But it’s all right, Ma– I’m only nerding.”

–not Dylan

Pingback: Didactic or Dynamic? Superheroes from the Middle East | Sacred and Sequential