There’s a strange phenomenon that sometimes happens in later seasons of television shows, where the weight of all of those previous years occasionally produces moments of metadialogue. It frequently appears as part of an effort to cope with the sheer unlikelihood of seven seasons of drama, the typical string of intensely emotional events which is unpunctuated by moments of normal, boring, every day life. A few weeks ago on Grey’s Anatomy, for example, a newer doctor asked sort-of protagonist Meredith Grey why Alex Kharev, one of the other remaining original characters, seems like such a jerk. “He’s been through a lot,” answers Meredith. “He had a girl go crazy on him, his wife almost died and then she walked out on him. And then he was shot and almost bled to death in an elevator.” It’s a weird moment; not only does it puncture the shoe’s admittedly-thin veil of plausibility (no one has that level of wackadoo tragedy happen to them in such a short span of time), but Meredith’s wryly explanatory list just draws attention to the oddity of Alex’s excessively eventful life. Grey’s Anatomy seems to be doing its best to brush over this bit of patent fictionality by hiding it in plain sight, but it’s hard to imagine writing or hearing the line without immediately recognizing the show’s artifice. Once you start looking for this kind of dialogue, you see it everywhere – detectives on cop shows grouse about how many dead bodies they see in a year, characters joke about that one time a few years ago when they were buried alive, long lasting characters look around and comment on the number of new hospital staff members after a particularly disruptive cast turnover. One of the characters on another Shonda Rhimes show, a therapist named Violet, frequently bemoans her bad luck, and at one point even asks – “Why does this sort of thing keep happening to us?” Because you’re on a primetime soap opera, Violet. Happiness does not make for good plot.

There was a particularly good example of this kind of metadialogue on the J.J. Abrams show Fringe a few months ago. (*Ahem*: Major Fringe spoilers ahead, if you’re concerned about that sort of thing). Fringe has undergone a pretty monumental transformation from the show that first appeared to the show currently airing on Friday nights. Initially, Fringe followed a formula made familiar by The X-Files, a police procedural with added supernatural elements – monsters and the unexplained spring out of the woodwork, and an eccentric, intrepid team of curious investigators searches for the reasons why (and the ways to stop it). Most new episodes came packaged with a new supernatural event which was handily dispatched by the hour’s end, and although some characters and plotlines hinted at a deep, dark secret in the background, that secret functioned asymptotically. Stories seemed to continually approach the point of uncovering the series’ organizing mystery, but they drew closer and closer without ever arriving at the mystery’s content.

Nothing says procedural like a cop in a doorframe holding up a badge

At some point during its second season, though, Fringe took a sharp right turn into the weird (and arguably, the better). Olivia and Peter, investigators of “fringe science,” along with Peter’s fabulously off-kilter mad scientist father Walter, discover and then travel to a parallel universe (the existence of which provides the underlying explanation for many of the previous season’s strange phenomena). The other universe, or “Over There,” is home to many doppelgänger versions of Fringe‘s original characters, including a much more fun-loving and freewheeling Olivia (who Peter dubs Faux-livia) and a powerful, sane version of Walter (Walternate). As it turns out, the rules of Over There are different from our own, and the course of history has shifted slightly, leading to the complete quarantine of Boston and much of the Midwest, a militarized society, a gold rather than green Statue of Liberty, and the continued use of zeppelins. (Zeppelins!)

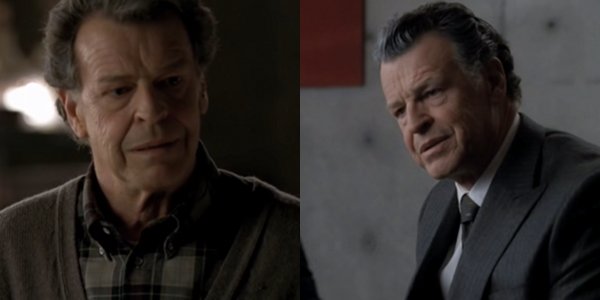

Walter vs. Walternate

The great thing about Fringe‘s Over There is that its entertaining, superficial differences also come with a new set of narratological paradigms. As Peter and Olivia discover, the breach between universes has led to the alternate universe’s gradual disintegration, and Walternate’s method of holding his world together frequently involves trapping thousands of unfortunate, innocent citizens in a timeless, motionless state – literally frozen in amber – in order to prevent the universe from unraveling. The stakes are much higher, and those simple Monster of the Week plotlines are no longer sufficient to represent or address the other universe’s terrifyingly fragile state. In their own universe, Peter and Olivia encountered and dispatched isolated pockets of oddity, leading to the show’s episodic and frustratingly static structure, but Over There, a monster is never just a single event. Any deviation from the standard laws of physics is a potential site of total, universal dissolution, and unless it can be stopped, hundreds or thousands of people could die in order to keep the world from simply falling apart. As a result, the show has drifted away from its initially episodic structure into something more serialized, allowing plots to expand beyond the boundaries of an hour to keep pace with the long-term goals of the main characters Over There, who have plans to save their universe that necessarily exist outside the moment of an individual bizarre occurrence.

I should mention that although the other universe introduced an entirely different set of narrative possibilities for the show, Fringe has not abandoned its episodic format. Instead, in a lovely convergence of form and content, the troublesome fictional breach between universes has been accompanied by blended narratological structures. Serialized plot lines often come packaged inside a particular, episode-length conflict, and those smaller procedural story lines no longer produce the same infuriating fictional stasis that plagued Fringe during its first season. In fact, Fringe has done a great job of using some of the often-ignored paratextual possibilities of the episodic structure to provide landmarks and signals inside its new multiverse. The show’s opening credits, previously a uniform blue, remain blue when the episode takes place in the show’s original universe, but turn red when the episode takes place Over There. (There’s also a third possibility, which allows episodes that take place in the past to begin with an awesome retro-themed credit sequence). In other words, it’s not just that the new universe changed Fringe from an episodic into a serialized show, but rather, both serialized and episodic elements became far more meaningful inside a multiverse where significant plot events might remain meaningful outside the space of a single episode.

All of which brings me back around to my initial point – that wonderful, weird moment of metadialogue that sparked this whole thing in the first place. At one point during a recent episode, Peter pauses in a serious discussion with Olivia about their troubled romantic relationship (he falls in love with Faux-livia, life gets very complicated) and asks, “does it ever feel like every time we get close to getting the answers, someone changes the question?” It does feel that way, and Peter’s right, of course. The questions have to keep changing, because otherwise, the search for answers would grow tedious, and once every question has an answer, the show has no purpose. But the line is particularly apt because Fringe stopped merely changing the content of the questions, and began to change the nature of the questions as well. It went from, “why does this man have a mechanical heart?” and, “how do we stop this mysterious virus?” to, “who has a stronger ethical code, Walter or Walternate?” and, “which universe deserves to be saved?”

I don’t want to suggest that Fringe is now perfect, or that purely episodic shows are necessarily inferior, or that any struggling scifi show should throw in a parallel universe and cross its fingers. But that line from Peter highlights the thing that’s helped move Fringe from an easily forgettable show into something effective and watchable – the questions change. Maybe it’s because Fringe has been under the threat of near-cancellation from its beginning, or because the voices involved in its production changed, or because it just took a season and a half to figure itself out, but Fringe’s malleability has kept it from succumbing to inertia. As a result, the monsters are scarier, and that moment of metadialogue which elicits such groaning on a show like Grey’s Anatomy, yields a wry smile instead.

_________

Update by Noah: You can read more of Kathryn’s writing at her blog.

I’ve never even heard of Fringe, though this kind of makes me want to see it.

I love the insight into the escalating ridiculousness of serial fiction though. I don’t know how familiar you are with comics…but I think it’s even more of a problem/clusterfuck in super-hero titles than it is in TV (except possibly for actual soap-operas?)

Most super-heroes have 40+ years of backstory, complete with compulsive retconning and alternative versions. And of course super-hero plots are even more improbable than your average sci-fi tv show, where at least no one wears their underwear on the outside….

Not sure this is of interest Kathryn…but here’s an essay I wrote about the problems of extended narratives for superheroes.

You must lead a really hermetic existence to not even have heard of Fringe. I’ll say that the above is a pretty accurate description of the flow of the series with the first season being not much more than an X-Files rip off, the actors flailing around like non-entities. It’s main failings are recurring factors in most other JJ Abrams related product: the tedious MacGuffins, the plethora of somewhat interesting plotlines without truly ingenious resolutions (the reverse of something like Deathnote for example) etc..

One problem with serialized fiction must be the numbers game. The second and third seasons of Fringe have shown dropping viewership figures as its audience gets alienated from its season long story arcs. On the other hand, episodic TV trash like NCIS continues to win big in the ratings.

i haven’t seen fringe, but anything long-running is fairly susceptible to major narrative problems. to the extent the plot remains episodic it spirals into endless repetition and attempts to up the ante become gimmicky (let’s blow up the enterprise! again!)

to the extent that they try to build an overarching world/story it either comes together and the show ends, or it keeps sprouting twists until you forget who anyone is or how the knot of causal threads turns into a compacted hairball (20th Century Boys, X-Men). the alternative universe twist in fringe sounds like a new ones but off the top of my head it could still become episodic, just with longer “saga-like” episodes, which kind of reminds me of the manga hunterxhunter. except in hunter x hunter it’s a bit like starting over from scratch each time and makes it hard to maintain cohesion throughout the overarching story. it sounds like you’re saying fringe does a good job of that?

i think the the solution of a lot of manga is pretty interesting. the goal seems to be to fit everything into an overarching sports-narrative where eternal forward-motion and unpredictable twists (who wins?) has some sort of plausible excuse, and leaves room for character development in the off season. it has a couple major problems as well. for one thing it kind of homogenizes all themes (not just sports and fighting but baking, rock’n’roll, politics, magic, ninja-espionage) to fit a spectator tournament where someone wins and someone loses. For another there’s the problem that in order to have some over-all rising action the “bad guys” often have to get tougher and tougher, which kind of deflates the action and stakes of any given fight when you know there’s an endless (or at least as long as the manga is popular) supply of guys who are even tougher than “the toughest guy I’ve ever faced” waiting their turn.

Fringe certainly has suffered from decreased viewers, but that drop off was happening even before it began playing around with longer story lines, and although I think serialized stories do often alienate an audience, in the case of Fringe, they actually helped hold on to what little audience the show still had. FOX recently moved Fringe to Friday nights, which is generally considered a programming death slot, but for the most part, the numbers haven’t suffered – it even got renewed for a fourth season, which is like some kind of television miracle.

I do want to leap to defend the concept of episodic serial stories – sure, they’re often crap, and NCIS is pabulum meant to induce comforting mindlessness. But a good standalone episode of television can also be fantastically entertaining, and thoughtful, and serious, and all the things we’re quick to assume comes only from more complicated, long arc storytelling. (Take, for instance, some of the episodic parts of the recently departed show Terriers, while I wipe away a tear in remembrance.)

To ave and Noah – my knowledge about comics fits comfortably onto half of one shelf of an ikea billy bookcase, so I have to bow to your much more informed thoughts on that area.

Yes, long running television series do run into huge narrative obstacles, but where you might say problems, I say opportunity for playfulness. (An opportunity that often isn’t employed, or if it is, fails miserably, but an opportunity nevertheless). Fringe is one example of a decision that kept the show moving forward in an interesting way, but successful long running shows have lots of these. Buffy survived the move out of high school, The West Wing went from great to terrible and then back to pretty good again (before being cancelled), Friday Night Lights managed to be completely awesome even after losing half its main cast, and Doctor Who! Doctor Who has been been around for decades, and the most recent series, which began several years ago, is some of the best scifi television out there right now.

In other words, just because long-running series often run into trouble doesn’t mean they have to, and it certainly doesn’t mean they can’t recover.

“Buffy survived the move out of high school,”

No, there I disagree. Losing its central metaphor was a disaster that the show never managed to overcome. Not that it was perfect to begin with, but those last seasons were godawful.

Angel, on the other hand, got better as it went along.

To each his own – some of my favorite Buffy eps are in the post-high school years. (Hush, The Body, and yes, I’ll admit it, Once More With Feeling).

Kathryn, the sort of “meta” you cite in the opening paragraphs has a long and honorable ancestry in popular culture.

For example, in Conan Doyle’s ‘Sherlock Holmes’ tales, there would often be tantalising references to cases never narrated, such as the ‘Canary trainer’ or, wonderfully, the case of “the giant rat of Sumatra– a tale for which the world is not prepared”.

This was a winking acknowledgement of the deliberate grotesqueness of the Holmes tales.

Closer to us HUmanoids, in comics, Superman in his Fortress of Solitude kept a zoo of weird and dangerous alien beasts…we kids would speculate over what unwritten adventures Superman had, bringing these monsters into captivity! It was a sort of game between the editors and the readers.

“Yes, long running television series do run into huge narrative obstacles, but where you might say problems, I say opportunity for playfulness.”

i don’t think the endless length = bad storytelling is an unbreakable rule or anything. i just say it’s a problem because i find so few long-running serial narratives to be exceptional, compared to novels and movies. by “long-running”, I mean say, greater than 10-15 volumes of manga or however many episodes that would translate into. i only have one or two exceptions in tv or comicdom that outlive that limit. i guess i’m in the camp that thinks buffy went downhill too.

Though I have not read any of the books of George R. R. Martin’s “A Song of Ice and Fire” series of novels, this article (which astonishingly fails to mention his “Fevre Dream,” the Second Best Vampire Novel Ever Written) in the latest “New Yorker” mentions some of the narrative challenges involved in this kind of complex, serialized long-term creation:

—————————

…there are already more than a thousand named characters in “A Song of Ice and Fire,” although many of them are mentioned only in passing…

The serial nature of “A Song of Ice and Fire” is key to the involvement it elicits. Although story lines conclude in each of the novels, the larger narrative arc remains unresolved, encouraging readers to speculate about what might ultimately happen. Online forums are an ideal place to debate rival theories, allowing participants to forge the emotional bonds that define contemporary fandom…

The proliferation of plot elements is a major reason that Martin’s writing pace has slowed. “A Song of Ice and Fire” primarily takes place over several years on a continent about the size of South America. Each chapter is narrated in the third person, from the point of view of a single character. The first book had eight major viewpoint characters, but by “A Feast for Crows” the total for the series had grown to seventeen, each in a different location and enmeshed in a complex plot—fighting in wars, journeying through arduous terrain, scheming to steal a throne.

Making sure that the chronologies of the different stories line up has particularly bedevilled Martin. He said, “I have to ask myself, ‘How long is it going to take this character to get from point A to point B by ship? Meanwhile, what’s happened in the other book? If it’s going to take him this long, but in the other book I said that he’d already arrived there, then I’m in trouble. So I have to have him leave earlier.’ That kind of stuff has driven me crazy.”…

Martin is in the unusual position of being a writer whose work is attended to even more closely by his readers than by himself. And, as the panorama of “A Song of Ice and Fire” has grown ever more expansive, Martin has become increasingly afraid that he’ll make mistakes. He has already made some tiny ones: “My fans point them out to me. I have a horse that changes sex between books. He was a mare in one book and a stallion in the next, or something like that.” The eyes of one supporting character are described as green in one passage and blue in another. As Martin puts it, “People are analyzing every goddam line in these books, and if I make a mistake they’re going to nail me on it.”…

—————————

http://www.newyorker.com/reporting/2011/04/11/110411fa_fact_miller

On another related vein, the article mentions…

—————————-

Martin knows what it’s like to be provoked by a serial entertainment. He experienced it himself as a faithful viewer of “Lost,” the ABC adventure series about a group of castaways trapped on a mysterious island. “I kept watching it and I was fascinated,” he recalls. “They’d introduce these things and I thought that I knew where it was going. Then they’d introduce some other thing and I’d rethink it.”

Like many “Lost” fans, Martin resented the series’s mystical ending, which left dozens of narrative threads dangling. “We watched it every week trying to figure it out, and as it got deeper and deeper I kept saying, ‘They better have something good in mind for the end. This end better pay off here.’ And then I felt so cheated when we got to the conclusion.”

——————————-

Yet, while “Lost” was going on, I wondered how the creators likely had their future narrative choices or planned revelations circumscribed by some fans guessing what they were planning to do, then — thanks to the Internet — broadcasting what (if the writers continued the plots they had in mind) would have been “spoilers” to millions of devoted audience members.

(BTW, we’re big fans of “Fringe” in this household. Fine write-up, Kathryn VanArendonk…)

To Alex –

Yes, Sherlock Holmes! So much great TV owes its form and tropes to Conan Doyle. What fascinates me most about this kind of writing, whether it happens in TV, comics, or the Sherlock Holmes semi-serialized short story sequence, is the way that a serial gap produces extra-textual thinking. You could imagine Watson writing about untold Sherlock Holmes stories in a mystery produced only in volume form, but the joke works so much better when there are literal spaces between fictional pieces for those missing stories to fill. In a slightly different sense, the dilated time frame taken up by serial narrative in television often creates audience amnesia, making it difficult to remember exactly what all has happened to any given character. In this case, the metacommentary functions by compressing that expanded serial time rather than pointing to its lacunae.

To Mike –

Thanks, and thanks for pointing out that New Yorker piece. I am pretty excited for the premiere of the GRRM Game of Thrones adaptation on HBO this weekend, and was entertained by Damon Lindelof’s quasi-indignation on twitter over Martin’s coinage of writing a dissatisfying end to a long serial narrative as “pulling a LOST.”

I watch this damn show every week then ask myself “why?” One gets a sense that the powers that be can hardly keep their focus, because then they might have to figure out where it’s going. I think it will probably end annoyingly disappointing like Lost, and I will have no one to blame but myself for taking the time.

As with “Lost,” my Significant Other and I enjoy the hell out of the individual “Fringe” episodes, twists and turns, and don’t fret over the big picture, much less are expecting to have All the Questions answered. (Hell, we didn’t even keep track of all the “questions” in “Lost”!)

Do others think all their years of excitement and delight in watching “Lost” were wasted, or end up tainted with disappointment because All the Questions were not answered in the end?

There’s a nasty surprise awaiting: when you’re dying, All the Questions of Life aren’t going to be answered, either. Was there a purpose to all this? What would’ve happened if you’d married ________ instead? Why do good people suffer and evil assholes thrive? Will the Average American ever realize that the Republican Party is not their friend? You’ll never know…

(Come to think of it, doesn’t much conspiracy thinking derive its force from the wish to have messy, complicated reality simplified and explained by the International Jewish Conspiracy or whatever pulling strings behind the scenes? Note how in troubled times, reactionary churches with their simplistic messages thrive, while liberal ones continue to dwindle.)

Wondering if somebody did one, I Google’d “lost tv plot chart”:

http://images4.wikia.nocookie.net/lostpedia/images/6/6c/Lostconnections.gif

(Alas, it’s actually just a character chart…)

…and also found this Harry Potter plot chart:

http://geektoplasm.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/11/harry-potter-plot-chart-1.jpg

Freytag’s [plot] Triangle:

http://www2.cnr.edu/home/bmcmanus/freytag.jpg

(From http://www.cherylklein.com/id12.html )

—————————-

TV Explained : Lost

TV Explained is a brand new, innovative solution for understanding what is going on in your favorite TV show. In this Lost edition you’ll never get confused by what point in time Sawyer, Kate, Jack and the rest of the gang are again.

TV Explained: Lost has been written and developed by a team of experts and fanatics of Lost. The app explains scene by scene what is going on, what is a flashback, what point of time the scene is set in and who on the island (and off it!) each character is. If you thought you knew all the secrets of the island, I’d check this app out first.

All you have to do is enter the Season and the Episode you are watching, followed by the time (hours, minutes, seconds) that has elapsed in that episode (eg Season 4, Episode 8, Time 00:15:16). You are then given a synopsis of that exact moment in the scene, including the plot, the characters, HIDDEN MEANINGS and anything else that you may have missed. You can also scroll back and forth between scenes to ensure you didn’t lose the plot at a different time.

As well as all this, there is a Character List with a photo and profile of the most pivotal characters in the show to help you further identify the ‘others’ from the crash victims.

TV Explained: Lost is the ultimate TV viewing aid!

TV EXPLAINED OTHER TITLES:

TV Explained: The Wire

TV Explained: Gossip Girl

————————

http://www.srelease.com/tv-explained-lost

It’s a widely accepted dictum among fiction authors that a short story can achieve aesthetic perfection far more easily than a novel, because it’s simpler.

So, imagine how much more messy and complicated things get in a series of books, or worse yet, a TV series, the latter employing many writers.

J.K. Rowling achieved a satisfying overall narrative arc in her Harry Potter books because she said she had in mind all along how the series would play out and end. The earlier noted “New Yorker” article mentions how George R.R. Martin’s vastly more complex series is likely hampered by the fact that “He thinks of himself as a ‘gardener’—he has a rough idea where he’s going but improvises along the way.”

I’d mentioned earlier how, while “Lost” was going on, I wondered how the creators likely had their future narrative choices or planned revelations circumscribed by some fans guessing what they were planning to do, then — thanks to the Internet — broadcasting what (if the writers continued the plots they had in mind) would have been “spoilers” to millions of devoted audience members.

If fanatic Dickens fans would’ve had the Victorian equivalent of an Internet, wouldn’t one in his blog predict that “A Tale of Two Cities” – published in 32 weekly installments – would end with (SPOILER ALERT) Sydney Carton sacrificing himself on the guillotine to save the life of his lookalike, Charles Darnay? This prediction then “going viral,” and forcing Dickens to feel he must then concoct another ending, which couldn’t help but be less dramatically satisfying and moving?

A messy, tangled, inconsistent Victorian serial:

——————-

Varney the Vampire; or, the Feast of Blood was a mid-Victorian era serialized gothic horror story…It first appeared in 1845–47 as a series of cheap pamphlets of the kind then referred to as “penny dreadfuls”… It is of epic length: the original edition ran to 868 double columned pages divided into 220 chapters. Altogether it totals nearly 667,000 words. Despite its inconsistencies, Varney the Vampire is more or less a cohesive whole…

Though the earliest chapters give the standard motives of blood sustenance for Varney’s actions toward the family, later ones suggest that Varney is motivated by pecuniary interests. The story is at times confusing, as if the author did not know whether to make Varney a literal vampire or a human who acts like one. Varney bears a strong resemblance to a portrait in Bannerworth Hall, and the implication is that he is one Marmaduke Bannerworth (a.k.a. Runnergate Bannerworth in a classic naming confusion), but that connection is never cleared up. He is portrayed as loathing his condition, but at one point he turns Clara Crofton, a member of another family he terrorizes, into a vampire for revenge.

Over the course of the book, Varney is presented with increasing sympathy as a victim of circumstances. He tries to save himself, but is unable to do so. He ultimately commits suicide by throwing himself into Mount Vesuvius, after having left a written account of his origin with a sympathetic priest. According to Varney, he was cursed with vampirism after he had betrayed a royalist to Oliver Cromwell and accidentally killed his own son afterwards in a fit of anger, although he “dies” and is revived several times in the course of his career. This afforded the author a variety of origin stories. In one of these, a medical student named Dr. Chillingworth applies galvanism to Varney’s hanged corpse and revives him…

———————-

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Varney_the_Vampire

Lost too went into the “close to but not the same alternative world” land that Fringe seems preoccupied with. It seemed like a clever and enjoyable spin on theoretical physics….but ended up being banal pablum about the afterlife. So…yes…this final “revelation” did, in some ways, “ruin” the end of Lost. It was a story with a beginning, middle, and end….and the end invalidated much of the middle. That’s why it sucked. Most murder mysteries DO reveal the murderer at the end. If they don’t (and some don’t), they’re usually “about” something else altogether (as in Auster’s New York Trilogy)…. Lost made itself out to be “about” a number of things and then didn’t fulfill its own premises. So…lots of Lost WAS super-enjoyable. That first season kicks virtually all other television’s ass (no, I haven’t seen The Wire)—and there are several “returns to form” over the life of the series— but part of the enjoyment is in the introduction of mysteries and the series’ implication that those mysteries have answers. It’s kind of a letdown to realize they had no idea what the fuck they were doing from the outset.

It’s a recurring problem in today’s episodic fiction. ‘Lost’, once it unravels its central mystery– whether lamely or masterfully– is DONE. ‘X-Files’, once the fate of the sister is explained, is done. Same for Alias. heck, go back to the ’60s and ‘The Fugitive’: once Kimball catches the one-armed man and clears his name, the series is over.

Networks don’t like that.

So the viewer is constantly subject to the deferred orgasm…

But narrative itself is largely about the deferred orgasm…Narrative “ends” tend to attempt to give satisfaction and to satisfy readerly “desire.” The narrative “middle”‘s job is to defer that desire, making you keep reading for the end. The overly prolonged middle (as in several years of episodes) can make one lose one’s sexual interest. There’s the real problem. In texts that promise no end from the outset (like “ongoing series” in comics—or soap operas), there may be alternative pleasures (or multiple orgasms)…”Mysteries” though…they’re basically all about the ending—so it better satisfy. There’s lots of “narrative theory” on this topic. Peter Brooks’ _Reading for the Plot_ is the classic “narrative works like (straight male) sex” position–but other theorists counter with discussions of soap operas among other things. Mysteries/detective fiction are the Platonic form of Brooks’ model of narrative though…

Seriously, it is getting really hard to tolerate watching the actress pretend to be Leonard Nimoy. Now they are taking acid….arrrghhh, with this crew it would have to be a bad trip, looks like a beat deal though.

It wouldn’t be so bad if she actually managed to pull it off. So far it just looks like bad acting.

Wait…are you guys live-blogging the current episode of Fringe?

Arrrrghhh. Well, at least we’ll never see that bit of hamming again.

Anyway, yes, I was kind of put out about wasting a lot of time on Lost when they completed it with a lot of twaddle. It proved they had no real story in the first place, not so bad of itself but unfortunately the ending they chose is what sticks in my head and would make me change the channel if a rerun ever comes on.