A few weeks ago Noah posted a link to an essay by Bert Stabler slamming the medium of art photography. Rankled by the dismissal of a fascinatingly diverse medium I agreed to write a rebuttal. However, rather than address the essay point by point, I’m addressing what I see as the fundamental flaw at the heart of Stabler’s essay, that the small, highly commercial subset of art photography that Stabler critiques is at all representative of the varied artistic power of photography by focusing on the work of several engaging contemporary artists who use photography in their practice.

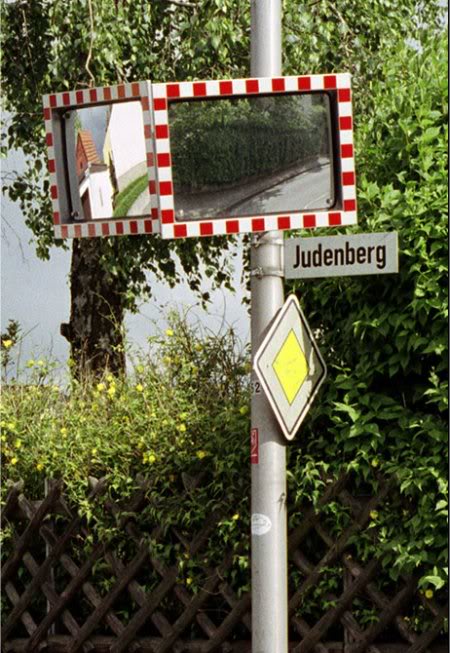

Susan Hiller’s work often focuses on the poetic systems behind the act of collecting, archiving and organising, perhaps the most striking of her ‘collection’ works is The J. Street Project. Encompassing three years of research, travel and photography, The J. Street Project is a massive collection of 303 photos documenting every street sign in Germany that contains the prefix Juden (Jew). Shot in a workmanlike fashion, the series is displayed in three formats; As a 606 page photo book of sequential photographs, as a 67 minute slide film, or as a monumental installation piece, pictured below.

While the individual photographs would appear as nothing more than a quirk, an oddity, it is the insistent mass and repetition of subject that gives this piece its incredible effect. Over and over, these mundane objects throw in to stark relief the dissonance between these German streets and the historical context of the country. Presented without comment, without drama, the audience is forced to fill the void of absence created by the work, projecting their cultural experiences in to the insistent work.

In the face of a modernity that demands constant efficiency and production, Alys’s Sleepers series forms a documentary of passive resistance. The work, comprised of 80 colour projector slides, depicts sleeper, both animal and human, engaging in an unusual relation to the urban construction.

Alys takes care to address the issue of the camera’s gaze in Sleepers as well, the subjects are always shot from low to the ground, or (or level with them in the case of bench sleepers), by joining his sleepers in such a way, Alys avoids what could have been a carousel of condescending ‘poverty porn’. Alys does not pity his sleepers, doesn’t look down on his subjects but lies with them, praising them for their ingenuity and their willingness to break with the social systems and rules of the modernised urban space.

Alys’s photographic vision in his other work cannot be ignored either. His photographic records of his performative and conceptual pieces is of particular note, here Alys excels at capturing and distilling the ‘defining image’ of a brief, ephemeral event. In ‘Turista’ we see this talent exemplified.

Here Alys strikes a comical figure, lanky, pale and absurd as he tries unsuccessfully to blend in to the line of trade workers in Mexico City. The picture poses a question and a humorous barb at the notion of the nomad artist, travelling between countries, gifting the people with their insights in to foreign cultures. Embodied and mocked by Alys, the notion becomes ridiculous, and we’re forced to ask ourselves, is the artist-nomad really a chameleonic nomad, able to fit in to any society and privy to mystic truths, or are they nothing more than a glorified tourist?

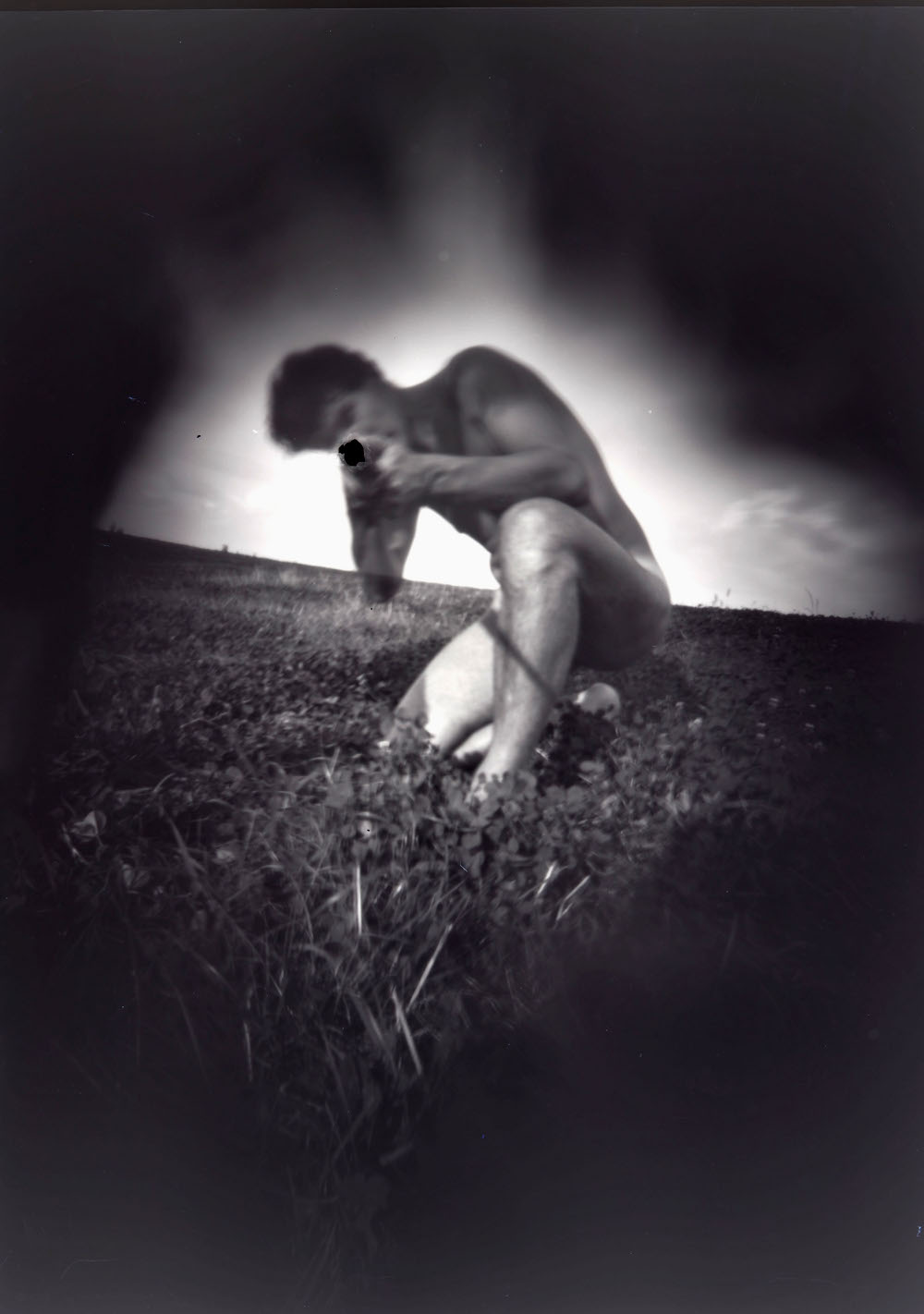

The camera has often been compared to a phallus, a weapon wielded by the photographer against subject. In the work of Jean Francois Lecourt that idea is taken to a delightfully absurd extreme.

The artist wields his camera as a gun and a gun as a camera, all targeted at his own nude body in an act of simultaneous destruction and creation.

Lecourt was inspired by old fairground games that still occasionally pop up around mainland Europe. In the game the participant is given a rifle and must shoot at a target mounted in the fairground stand, if they hit the bullseye, a camera automatically shoots a picture of them shooting the target.

Lecourt created a large, lightproof box to house a sheet of photosensitive paper, a kind of pinhole camera without the pinhole. He then stripped naked and fired a shot at his home made camera, simultaneously piercing the camera and the paper behind.

The resultant picture is a beautifully hazy, moody thing, recalling the dramatic light of a Noir film,. Lecourt’s pictures capture your eye, drawing you in with their strangeness. The eye’s registering of the depth of the photo is constantly baffled by the literal punctum of the gunshot hole, which seems to overlay the image like an abstract supernova, pulling the viewer’s eye constantly to the surface and reminding them of the object hood of the photograph.

The wit of Lecourt’s technique is wonderful to me as well, the idea of the nude male artist wielding the phallus of the gun against the phallus of the camera in an act of symbolic suicide that mocks the narcissistic romance of the self destructive artist, the artist shooting himself in both senses of the word and ending not with oblivion, but with another image of his own body.

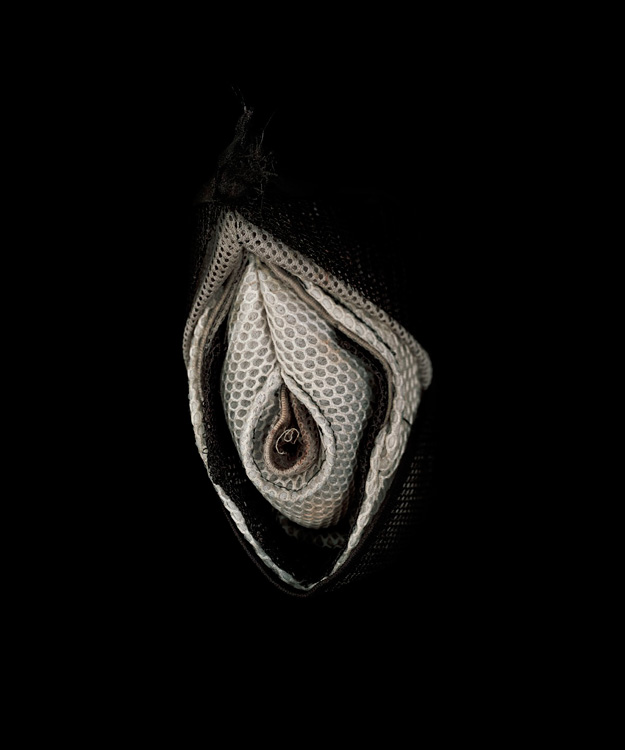

Danny Treacy’s work addresses the things we leave behind, travelling to out of the way or marginalised areas, the kind of places where people go to be alone and unseen together. Treacy collects trophies of abandoned clothing found in these areas, turning them in to sculptural subjects for his photographs that harness the suggestive, intimate untold histories behind the abandoned clothes to create a haunting mood that is as sensual and beautiful as it is haunting and inexplicably frightening.

In ‘Those’, Treacy’s first series, the artist created a series of organically suggestive sculptures using found fabric. These sculptures are all what Danny calls ‘protuberances’, the things that stick out from us, that enter the world and, through their orifice like openings, invite the world to enter them, to gaze in to the soft folds of their innards. Named as Those, they become empty, out of place things, without noun, signs awaiting an object, as alien as they are enticing.

The bizarre, erotically charged organs are shot intimately, close up against a plain black background, leaving the eye to wander over the sensual surfaces of the soft fabrics that Treacy employs. Through the forensic eye of Treacy’s camera, the erotically charged sculptures discharge their intimate history and morph in to a proxy of the human flesh they once covered. One wishes they could reach out, to touch the sculptures, to reach inside and feel them.

Treacy’s other series, ‘Them’, continues the artist’s obsession with the discarded skins of our clothes, the ‘Them’ are different however, the name itself recalls horror movies of bygone eras, and the ‘Them’ indeed are a kind of monster. Constructed from mended and sewn together pieces of clothing, the Them become sad, tragic figures, haunting and frightening as they loom from the darkness, filled with the body of the artist himself, who claims to feel a kind of protection and comfort from within the shambolic, anonymous suits he constructs, a connection with an intimate history of the abandoned garments in to which he has breathed a new and unnatural life. To us on the outside though, the figures are threatening presences, each unnameable stain evoking the hidden histories of the things we carelessly abandon, reminding us that every piece of clothing was witness to the fate of their owners, whatever that may be.

Fine article, Thomas O’Shea! Though it looks like links to both the Stabler essay and “Proximity” magazine are out of whack. (At least this ‘un is currently working: http://proximitymagazine.blogspot.com/ )

I did run across “Some remarks about Bert Stabler’s ‘I Don’t Like Photography’”: http://jmcolberg.com/weblog/2009/10/some_remarks_about_bert_stablers_i_dont_like_photography/

Being pretty damn intimately aware of the history of photography as art, though unaware of most going on there for the last few decades (aside from awareness of brilliant talents like Joel-Peter Witkin), the fragments from Stabler’s essay come across as dubious, to put it kindly. That brattish title, “I Don’t Like Photography” (or eating your veggies, probably) hardly adds to the intellectual cachet.

——————

Stabler’s third ‘P’, “‘Pentax’ denotes the fetishization of equipment, techniques, and software, everything from pinhole cameras and photograms to clever Polaroid processes to high-end old-timey analog large-format film cameras to elaborate exposures to messing with reality in Photoshop…

—————–

Clearly Stabler hasn’t spent much time among the painting crowd; I’ve dozens of magazines and books where the virtues of Kolinsky over regular sable bristles are extolled, where the minimal array of brushes a painter needs are delineated; with much discussion of primers, oil vs. acrylics, endless attempts to rediscover and resuscitate Old Master painting formulas, analyze Titian’s underpainting approach, the lighting of de La Tour, debate alla prima versus glazing, types of varnishes, wood vs. Masonite for painting on panel, and so forth.

Is this “fetishization” or a fascination with tools for achieving desired ends?

—————–

Maybe trying to re-affirm his credentials, the author resorts to quoting the usual suspects (Lacan, Foucault, Adorno). If one needed proof that inserting postmodern philosophy into discussions about art does little (if anything) to further our understanding of art all that much, here is one.

—————–

Jeez, another “theory-head”! I should’a known…

—————–

Collecting fine art remains a duty for a dwindling aristocracy, and a trophy hunt for the money-laundering nouveau-riche, but its larger purpose in the culture has come to be formed in an arena fenced in by the professional discourses of academia, the taste-crafting marketing elite, and the reputation economics of semi-public cultural cathedrals—where bits of art trickle down into the assessment machines and mission statements of nonprofits and educational institutions. These competing agendas have drowned out any clear extrinsic purpose for fine art…

—————–

http://bertstabler.com/home.html

Somebody hit this man in the face with a pie, please…

Proximity does seem to be down; here’s a cache of Bert’s article though.

Edit: and I can’t get the cache to show up. Sorry….

I don’t not like pie. Hurl away!

Mike, you’ve sen my deluded attempts to think using books in the threads with Caro and Franklin. I’m sure you remember my churlish blatherspouts.

I like the German street sign series. I don’t have any major problem with documentary photography when it’s not being used to, say, document homeless people (the “poverty” p), as Alys does. Documenting street signs and documenting sculptures or performances or whatever is fine- that’s what normal people do with photography (not performance art or sculpture, but just documenting things they care about).

Just a note Bert, Alys’s sleepers series isn’t just documenting homeless people, it’s documenting anyone (and some dogs) asleep in public, tourists, street sellers, workers on their break etc. There’s definitely some homeless people in there but it’s more about the strange relation Mexico City has with things that we take for granted as normal codes of modern urban life.

Alys’s beggars series is more what you’re talking about, I’m not a fan of that series at all though for the same reason.

I’m really not a fan of that Alys stuff. Even if it’s not all homeless people, it just seems really half-assed, I guess, formally and conceptually. The Hiller seems pretty boring too, honestly. The Lecourt is pretty great; that first image especially is beautiful and disturbing. And I’m mixed on the Treacy….

It’s all sort of about where it comes from as an art project. The sign documenting is sort of a Fluxus thing– like writing down what you had for breakfast every day for ten years, or the performer who took a picture of himself every hour for a year. The shooting penis thing is completely Chris Burden performance, and the Treacy sculptural things are Mike Kelley pieces, just photographed.

It’s fine if people like the Alys shots, but I totally find it exploitive and smug, and thoroughly in keeping with my objections against art photography (sort of dreadful just in its anxious qualification– like “literary fiction,” or “alternative comics.”). Like that Turista shot.. you know there are light-skinned Mexicans. Which, as everywhere, implies a caste system, but the guy isn’t necessarily a tourist. Certainly no more than Alys.

‘Like that Turista shot.. you know there are light-skinned Mexicans. Which, as everywhere, implies a caste system, but the guy isn’t necessarily a tourist. Certainly no more than Alys.’

That IS Alys in the photo, it’s a document of a performance he did.

Fair enough. That’s big of him.

——————-

Bert Stabler says:

I don’t not like pie. Hurl away!

——————–

Even though a cake man myself, I’d much rather eat the pie…!

——————–

…I don’t have any major problem with documentary photography when it’s not being used to, say, document homeless people (the “poverty” p), as Alys does…

———————

That earlier bit:

———————

Thomas O’Shea says:

Alys takes care to address the issue of the camera’s gaze in Sleepers as well, the subjects are always shot from low to the ground, or (or level with them in the case of bench sleepers), by joining his sleepers in such a way, Alys avoids what could have been a carousel of condescending ‘poverty porn’. Alys does not pity his sleepers, doesn’t look down on his subjects but lies with them, praising them for their ingenuity and their willingness to break with the social systems and rules of the modernised urban space…

———————-

What, is expressing sympathy for those who are worse off than we are, trying to call attention to their plight via photojournalism, thus unavoidably tainted as being “condescending”? (In the same fashion many irate feminists would chuck all nude paintings in the trash as expressions of that oppressive “male gaze”; no matter how compassionate or nonexploitative they might be.)

Is it better to not give a shit, or somehow depict the sorry condition of what are surely mostly homeless folks as heroic, “praising them for their ingenuity and their willingness to break with the social systems and rules of the modernised urban space”? Might as well describe dumpster-diving in the same fashion.

I’ll never forget some townhall meeting-type occasion where George W. Bush fielded questions from “reg’lar folks.” This lady told him of how she was having to work 3+ jobs to make ends meet; having to rush and feed her kids before taking off for the next one. George W. enthusiastically said, “Isn’t that great? You sure are doing a fantastic job!” and the audience – manipulated with absurd ease – applauded this “admiring salute” to the woman’s ingenuity and hard-working drive.

From someone who should be sympathized with, deserving of being offered help, George W.’s words turned her into a hero to be admired; for whose plight (oh, let’s call it a “challenge”; sounds ore pseudoheroic) we need not lift one finger.

The greatest American photojournalist, W. Eugene Smith, in “Minamata” documented the situation of Japanese villagers exposed to toxic wastes from an industrial plant; their fishing poisoned, children afflicted with birth defects.

Industrial waste being dumped into their water: http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/en/9/93/Minamata_Chisso_Industrial_Waste.jpg

A mother bathes her deformed child: http://www.smashboxstudios.com/yello/wp-content/uploads/2010/10/smith_minimata.jpeg

“Tomoko’s hand”: http://rgsbio09.wikispaces.com/file/view/Tomokos_hand.gif/84689941/Tomokos_hand.gif

———————

Minamata disease was first discovered in Minamata city in Kumamoto prefecture, Japan in 1956. It was caused by the release of methylmercury in the industrial wastewater from the Chisso Corporation’s chemical factory, which continued from 1932 to 1968. This highly toxic chemical bioaccumulated in shellfish and fish in Minamata Bay and the Shiranui Sea, which when eaten by the local populace resulted in mercury poisoning. While cat, dog, pig, and human deaths continued over more than 30 years, the government and company did little to prevent the pollution…

Photographic documentation of Minamata started in the early 1960s. One photographer who arrived in 1960 was Shisei Kuwabara, straight from university and photo school. The first exhibition of his work in Minamata was held in the Fuji Photo Salon in Tokyo in 1962, and the first of his book-length anthologies Minamata was published in Japan in 1965. He has returned to Minamata many times since.

However, it was a dramatic photographic essay by W. Eugene Smith that brought world attention to Minamata disease. He and his Japanese wife lived in Minamata from 1971 to 1973. The most famous and striking photo of the essay, Tomoko Uemura in Her Bath, (1972) shows Ryoko Uemura, holding her severely deformed daughter, Tomoko, in a Japanese bath chamber. Tomoko was poisoned by methylmercury while still in the womb. The photo was very widely published…Smith and his wife were extremely dedicated to the cause of the victims of Minamata disease, closely documenting their struggle for recognition and right to compensation. Smith was himself attacked and seriously injured by Chisso employees…in an attempt to stop the photographer from further revealing the issue to the world.] The 54 year-old Smith survived the attack, but his sight in one eye deteriorated and his health never fully recovered before his death in 1978.

————————

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Minamata_disease

What a jerk, that Smith, with his condescending “disability porn”!

An array of photojournalism from the Vietnam War: http://www.tampabay.com/blogs/alleyes/content/vietnam-war-ended-april-30-1975-23-images . Most – if you’re of a mind to – liable to be rejected as “condescending,” “exploitative,” “manipulating our emotions”…

————————

Bert Stabler says:

Documenting street signs and documenting sculptures or performances or whatever is fine- that’s what normal people do with photography (not performance art or sculpture, but just documenting things they care about).

————————

So what “normal people do with photography” is OK, then? Thus, photos of moronically drooling babies or their dogs doing something cute — “normal people…just documenting things they care about” — rise triumphant over the work of Edward Weston, Lartigue, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Paul Strand, Walker Evans…

You too, Les Stone! “Untitled” (Haiti, Voodoo), 1996: http://www.likeyou.com/files/fullimages/les_stone2_pierogi_08.jpg (More info at http://www.likeyou.com/en/node/6680 )

Ironic how right-wingers likewise sneer at attempts by photographers to elicit concern for the suffering and downtrodden; the organizers of the “entartete Kunst” exhibit would surely praise volksfotografie over degenerate arty stuff…

(No, I don’t remotely think anyone here’s a right-winger; but it’s ironic how viewpoints sometimes coincide, though. As when feminists joined with the far right in attacking porn…)

Mike, your expressions of concern for the downtrodden juxtaposed with your sneering elitism nicely encapsulate the problems with art photography’s poverty porn.

I’m not saying there’s no room for photography helping call attention to atrocities or the plight of people in need, but there’s also a very large subset of documentary photography that pretends at this but instead simply exists to reaffirm people’s classist or colonialist beliefs of another group, to make them feel better because they can say ‘poor them, aren’t we much more developed?’ and then continue on their merry way, reassured of their false, condescending ideas of this ‘other’ group.

Mexico (and other areas of Latin America) especially has a long and troubled history with this kind of photography and with their agency as a culture being overshadowed by colonialist ideas of the country as a third world or developing nation. Alys’s work often addresses these assumptions of the outsider about Mexican culture. When you sit down and spend longer watching the carousel slide projection of the series you start to notice the details that challenge your original assumptions of the people in the pictures as objects of pity. For example, look closer at the two people in the photos, the first man’s beard is trimmed, he’s wearing what looks to be a spotless tailored suit jacket, the second’s more ambiguous, but the changes of clothing, the clean brightly coloured towel and the odd cleanliness of the blanket all suggest something more’s going on. In other photos, several of the sleepers are better dressed than I am day-to-day (funnily enough I’ve both slept in public and been mistaken for homeless before, despite being comfortably middle class for most of my life).

P.S. Dumpster diving rules and helps offset the hideous wastage of our food industry, I know a lot of people who’d be incredibly pissed off at you if you for assuming they need pity because they do it.

———————–

Noah Berlatsky says:

Mike, your expressions of concern for the downtrodden juxtaposed with your sneering elitism nicely encapsulate the problems with art photography’s poverty porn.

———————-

Who’s the target of my “sneering elitism”? University-educated, jargon-spouting “theory-heads”? Those who argue that documentary photography depicting the homeless is automatically exploitative, morally dubious? And, in what way is that elitist?

If there’s any sneering elitism here, it’s of the type of the woman on the right, in Weegee’s famed “The Critic”: http://museum.icp.org/museum/collections/special/weegee/images/wg1-64.jpg

(Though I’m all for elitism, provided the qualifications are rightful rather than dubious.)

…And you use “art photography’s poverty porn” as if it were a fact, rather than a perception from a specific point of view.

————————-

Marcus says:

I’m not saying there’s no room for photography helping call attention to atrocities or the plight of people in need, but there’s also a very large subset of documentary photography that pretends at this but instead simply exists to reaffirm people’s classist or colonialist beliefs of another group, to make them feel better because they can say ‘poor them, aren’t we much more developed?’ and then continue on their merry way, reassured of their false, condescending ideas of this ‘other’ group.

—————————

Examples, please.

And, couldn’t the photojournalism examples I posted links to be likewise smeared as pretending to show concern for victims of war and industrial pollution, and only reinforce their liberal audiences’ smug beliefs that they’re so much enlightened and environmentally-concerned?

How are the photographers to prove they’re not guilty of cynically cranking out “war is Hell porn,” “disability porn”? And that all their work is therefore to be smugly dismissed?

—————————-

P.S. Dumpster diving rules and helps offset the hideous wastage of our food industry, I know a lot of people who’d be incredibly pissed off at you if you for assuming they need pity because they do it.

—————————-

As a face-saving attitude, they may feel they don’t need pity, but those forced to resort to dig among rotting food, rats, roaches, and broken glass for sustenance certainly deserve it.

And pity — as evoked by “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” or the works of Dickens — can be a powerful motivator to change unjust, inhuman situations.

Alas, nowadays, we have the Right attacking the impoverished as totally to blame for their condition, ’cause they’re lazy and immoral; and others saying that we shouldn’t “condescend” to them.

Let’s see how the poor would appreciate hearing, “We’re going to cut off your welfare checks and food stamps, because we’ve been told it’s condescending and paternalistic.”

In your last comment, you mocked the suggestion that the photography of ordinary people could possibly be interesting.

“Thus, photos of moronically drooling babies or their dogs doing something cute — “normal people…just documenting things they care about” — rise triumphant over the work of Edward Weston, Lartigue, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Paul Strand, Walker Evans…”

In short, the people who Walker Evans photographs are interesting because he photographed them. Their own interests (their dogs, their kids) are moronic.

Oh…and that link to Bert’s article in the essay is functional again, so people should click through and read it if they haven’t.

‘As a face-saving attitude, they may feel they don’t need pity, but those forced to resort to dig among rotting food, rats, roaches, and broken glass for sustenance certainly deserve it.’

Here’s a good example of the kind of attitude I mentioned actually. Dumpster diving is not like this at all, food shops throw away food, especially baked goods and vegetables fresh and edible (because otherwise they can’t say things like ‘baked fresh every day/ picked fresh this morning’), in their own sealed plastic bags, you don’t eat rotting food, you don’t have to dig through garbage and broken glass, I’ve sat down at Vegan sharehouses to dinners nicer than what you could get from a fancy restaurant made almost entirely out of dumpster dived ingredients.

‘Examples, please.’

Well, just for a start, there’s the numerous complaints Detroit residents have been making about the photojournalism of their city and how unhelpful, sensationalized and inaccurate it is.

You get worn down trying to show them all the different sides of the city, then watching them go back and write the same story as everyone else. The photographers are the worst. Basically the only thing they’re interested in shooting is ruin porn. – James Griffioen, Detroit based artist.

See also the introduction to this article which points out how the ruin porn of the abandoned central station completely ignores the incredible artistic rejuvenation projects going on just across the street.

http://blog.art21.org/2011/03/30/living-in-the-present/#more-38228

———————–

Noah Berlatsky says:

In your last comment, you mocked the suggestion that the photography of ordinary people could possibly be interesting.

————————

Ah!

————————-

“Thus, photos of moronically drooling babies or their dogs doing something cute — “normal people…just documenting things they care about” — rise triumphant over the work of Edward Weston, Lartigue, Henri Cartier-Bresson, Paul Strand, Walker Evans…”

In short, the people who Walker Evans photographs are interesting because he photographed them. Their own interests (their dogs, their kids) are moronic.

————————-

Now, nobody better say that our cats are moronic!

The subjects of a work of art pretty much remain the same, whatever the talent or lack of same of whoever photographs them. It’s the work, the approach, which ends up making a subject look interesting. Thus, some Diane Arbus photos of a kid’s birthday party would be more aesthetically worthy than those taken by their parents, or a simply technically-skilled pro photographer, who definitely would know better than to try and capture any creepy expressions or unsettling moments, as Ms. Arbus would.

I’m “elitist” in believing that great artists are infinitely more likely to produce fine work than Joe and Jane Average. (How undemocratic…!)

Occasionally some “normal people” – to use Bert’s phrase – might come up with a striking photo. But, as shown by the near-universal mediocrity of “Sunday painter” art, it’s more a happy bit of luck – “one-time glory,” as one great photog called it – than the result of creative talent.

(I enjoy picking up old family photos in antique shops. Nothing of substantial artistry there, but the different “look” of old-time faces, clothing, toys; guessing at the personalities half-exposed in those formal settings, etc., have their own appeal.)

—————————–

Oh…and that link to Bert’s article in the essay is functional again, so people should click through and read it if they haven’t.

——————————

Hoo boy! Just when I was about to say, I didn’t want to go and replicate at HU the endless back-and-forth arguments that many found so off-putting at the TCJ message board…

But as it turns out, Stabler’s whole essay turns out to be beautifully written, rich in food for thought — indeed, too damn dense with ideas to mentally digest with ease — with some delish touches of wit, and refreshingly light on jargon.

(Sure makes me feel old when, aside from Cindy Sherman, I never heard of any of these new photographers…!)

——————————

Bert Stabler says:

“Poverty” describes a voyeuristic urge to claim that the same authenticity that is projected on to the anguish of a suffering face applies reciprocally to the image, its maker, and its viewer…

——————————

Wonder if Woody Allen had mocking that attitude in mind when one of his characters sported a huge print of that “suspected Viet Cong being shot” photo in his apartment? (Good Lord, it was even bigger than I remembered! http://blogs.suntimes.com/scanners/2007/10/blood_rights.html )

There certainly was an interesting effect at work when Irving Penn — who “began his career taking photographs for the covers of American Vogue in 1943 and became one of the most influential photographers of the post-war period” — went from shooting models and fashions, glamor work which wasn’t taken seriously as art, to doing “…a whole series of pictures of cigarette butts found on the street…printed 24×36 using platinum/palladium printing…”*, and all of a sudden got critical “respect”…

http://nicholasspyer.wordpress.com/2010/09/30/the-fashion-of-cigarette-butts-irving-penn/

——————————

“Despite working at Vogue magazine since 1943, Penn did not have an exhibition at MoMA until the mid-Seventies show of the cigarette butt series that, to me at least, must be seen in their monumental original size to be fully appreciated…But there was another sort of ambiguity or tension regarding the exhibition as well. John Szarkowski in his wall essay acknowledged in passing Penn’s commercial work in the world of ‘haute couture or cuisine’ and said, with what appeared to be almost an apologetic sense of embarrassed dismissal, that ‘one might guess that he [Penn] has only rarely enjoyed more than a cursory interest in the nominal subject of his [fashion] pictures.’

“At the same time, it is hard to escape the sense that Penn was not being sardonic himself about this issue of his primary home being located in the ghetto of commercial photography. He had to be smiling to himself and at himself that, after three decades at the top of the profession, cigarette butts became his key to the pantheon. It’s not that Penn pulled a fast one, per se. The cigarette butt work reflects keen intellect and craft, but it is interesting to contemplate all the subtle elements of the wit and schmaltz that Penn also brought to that particular proceeding.”

————————————-

Emphasis added; from http://theonlinephotographer.typepad.com/the_online_photographer/2009/10/irving-penn-fashion-photographer.html

* Second quote from http://forums.dpreview.com/forums/read.asp?forum=1007&message=5233130

Thanks for the dumpster-diving correctives, Marcus; your post came in while I was preparing and posting my last one.

As it turns out, I had to for the first time climb into a dumpster at my storage facility a few weeks ago, to retrieve some boxes of papers which I’d finally tossed. Then, naturally, needed them the very next day! And though it was mostly empty and had little food moldering away, few bugs and no rats, it was dangerously difficult to get in and out of (even if I brought two short stepladders), slippery, and fairly gross.

You must have nicer dumpsters in your part of the country!

————————–

Marcus says:

Well, just for a start, there’s the numerous complaints Detroit residents have been making about the photojournalism of their city and how unhelpful, sensationalized and inaccurate it is.

You get worn down trying to show them all the different sides of the city, then watching them go back and write the same story as everyone else. The photographers are the worst. Basically the only thing they’re interested in shooting is ruin porn. – James Griffioen, Detroit based artist.

—————————

I can understand the frustration; but, what makes a more interesting photo subject, a tidy suburban neighborhood or some burned-out hulks?

Am reminded of the Chinese government’s frustration when foreign tourists were more interested in shooting “backward” old pagodas and temples instead of the new hydroelectric plants the officials were so proud of…

I can understand the frustration; but, what makes a more interesting photo subject, a tidy suburban neighborhood or some burned-out hulks?

You tell me

http://blog.art21.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/04/photo3.jpg

http://blog.art21.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/04/heidelberg1.jpg

http://badatsports.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2011/04/wire-car-cruise.jpg

http://badatsports.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2011/04/oscar.jpg

personally I’d take these (well, the first one without that awful filter effect for preference) over abandoned buildings any day.

Mike: No problem on the dumpster diving thing, the good food tends to be the last thing thrown out on a business’s day, so it’s usually just sitting in a bag at the top of everything, nothing more needed than the occasional crate or a friend to boost you up for an especially large dumpster.

That Detroit series on Art 21 is great. There’s so much good stuff going on in Detroit. I might be writing about it for the Chicago Reader, but I am a bit of an ignoramus– I just know about the blog and a few cool curatorial projects.

I hate to flog my prose, but here’s a thing I wrote on this video artist Renzo Martens who’s doing incredible stuff with midery voyeurism in war zones: http://proximitymagazine.com/2008/12/circus-of-suffering/

“misery voyeurism.” My bad.

Bert: The artist I quoted might be a good place to get some info on Detroit projects, he’s got a website with his email address, it sounds like he might welcome someone actually interested in the non ruin stuff going on there.

http://www.jamesgriffioen.net

looking over his website he’s got some beautiful stuff on there too, really makes Detroit look gorgeous.

Oh! And thank you for your kind words, Mike. Sorry for the afterthought.

And Marcus, thanks II!

————————-

Marcus says:

[Mike quote] “I can understand the frustration; but, what makes a more interesting photo subject, a tidy suburban neighborhood or some burned-out hulks?”

You tell me

http://blog.art21.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/04/photo3.jpg

http://blog.art21.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/04/heidelberg1.jpg

http://badatsports.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2011/04/wire-car-cruise.jpg

http://badatsports.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2011/04/oscar.jpg

—————————-

Damn; your idea of what makes for a “tidy suburban neighborhood” sure is a lot different than mine.

I Google’d “tidy suburban neighborhood” and got a batch of images like…

http://www.soldonklamath.com/images/SOLD59225-3941KELLEY.jpg

http://tinyurl.com/3umrenj

http://tinyurl.com/3jkezma

I remember I was teaching an art class in an impoverished area of Chicago’s west side about a decade ago now, an area full of lush overgrown lots like the ones James Griffioen photographs, and one day I had a painter friend visit while taking the kids out to do some watercolor landscape painting in their neighborhood. My friend got completely pissed off that I was romanticizing their poverty, and forcing them to participate in it (the kids seemed perfectly happy to be outside, and made some nice sketches, with various levels of enthusiasm).

I admit it would be sort of more fun to have them do paintings of the tidy suburban homes Mike found, but it’s sort of a Renzo Martens thing (the guy I wrote about)– if misery is their only viable industry, why should privileged artists or journalists be the only ones getting paid for it?

Pingback: ? This Sunday, while cleaning up my bookmarks ? | Nihilsentimentalgia