This was first published on Splice Today. I thought I’d reprint it since I talked about Stanley Hauerwas here earlier in the week.

_________________________

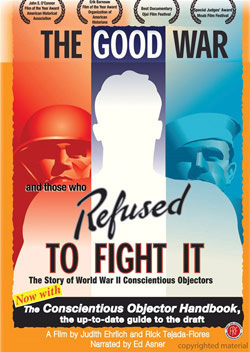

When I first thought to write about The Good War and Those Who Refused to Fight In It, a 2000 PBS documentary recently released on DVD, the U.S. was only involved in two wars. In the time between pitching the idea and receiving the documentary, the U.S. picked up a third. So now we’re fighting in Afghanistan, Iraq, and Libya. Possibly by the time this is published, we’ll have taken on a fourth. Obama hasn’t shown much desire to invade Iran, but maybe he’ll get a sudden inspiration. Who can tell?

When I first thought to write about The Good War and Those Who Refused to Fight In It, a 2000 PBS documentary recently released on DVD, the U.S. was only involved in two wars. In the time between pitching the idea and receiving the documentary, the U.S. picked up a third. So now we’re fighting in Afghanistan, Iraq, and Libya. Possibly by the time this is published, we’ll have taken on a fourth. Obama hasn’t shown much desire to invade Iran, but maybe he’ll get a sudden inspiration. Who can tell?

“The Good War” of the DVD title refers, of course, to World War II. But it could refer to Libya too…or either Iraq war, or the Civil War or World War I. All wars are good wars. Who would fight in them if they were bad?

Oddly, given the title, the question of good wars and bad wars doesn’t really come up much in this documentary. A couple of COs do note that, given Hitler and Pearl Harbor, WW II was an extremely difficult war to opt out of. One objector says that, when asked what should be done about Hitler, he had no response. Another suggests that the U.S. was not willing to try the program of peace — but the interviewer doesn’t ask what exactly that program might have been, and so it remains a mystery.

Instead the documentary mostly focuses less on sweeping ethical dilemmas, and more on the individual histories of the COs. The result is a typical PBS experience. Lots of people are interviewed in front of bookshelves. Lots of period footage rolls by as obtrusive music tells you how to feel about, for example, the insane asylums where many COs worked. Lots of earnest narration is delivered in a voice similar to Ed Asner’s (said narration provided, in this case, by Ed Asner himself.)

There’s nothing especially wrong with any of that. For those already familiar with the story of COs in WWII, I’d imagine that this would offer little new — but for people, like me, who haven’t studied the period, there’s plenty of interesting detail. Perhaps the most intriguing section, for me, was the discussion of how many COs volunteered for medical experimentation. Stung by charges of cowardice, a number of COs allowed themselves to be starved nearly to death or to be injected with hepatitis and typhus. Some died. The documentary doesn’t mention what, if any, useful knowledge was gained from these endeavors. I presume if life-saving drugs had been developed, they would have told us. It seems likely, therefore, that these men, out of a mixture of personal pride and societal pressure, sacrificed their health and risked their lives for nothing but the career advancement of bureaucrats. They might as well have been in the army. Except, of course that they didn’t have to kill anyone.

It’s nice to see evidence that pacifists can be as foolishly macho as anyone…though you have to tease that insight out from the general tone of benevolent hagiography. Admittedly, if you’re going to idolize someone, these folks seem like a decent bunch. Bill Sutherland, longtime advocate for African-American rights and a committed pacifist, talks with admirable equanimity about how his four years in prison was not an interruption of his activism, but an extension of it — he spent his time inside fighting prison segregation. Sam Yoder, a Mennonite CO, comments with rueful humor that when he returned home after the war, “no band was there to welcome me back” — and then proudly announces that his own two sons have obtained CO status.

What’s for the most part missing from these tales of individual heroism, though, is a sense of how they connect to a wider picture of war, peace, and community. The logic of war isn’t built on individual heroics. That is, people see service in war as heroic, but war isn’t usually justified on the basis of that heroism. It’s justified on the basis of its effectiveness. You defeat the German hordes by bombing them. You defeat the evil Libyans (in aid of the good Libyans) by bombing the first (and, ideally, not the second.) Heroism is nice, and will be celebrated, but it’s not exactly the point.

There’s no similarly utilitarian argument voiced here on behalf of pacifism — at least not with any consistency. Instead, everyone agrees you should stay true to your conscience. In one of many mini-bonus-documentaries included on the disc, for example, Daniel Ellsburg argues that he was truer to himself and to his patriotism when he released the Pentagon Papers than when he enlisted. And he’s both moving and convincing when he says it. But…what if your conscience tells you to go off and kill Japs? What if your conscience tells you to bomb Libya in order to prevent a genocide? Does that mean that some people are right to go shoot each other and others are wrong? Are there different ethics for different people depending on what conscience God happened to hand them?

It’s clear that many of the people here don’t believe that. Kevin Bederman, an Iraq war CO interviewed for another mini-doc, characterizes war (in an engaging Southern drawl) as “the most base thing human beings can do to each other.” Other COs note the importance of love. Some reference Ghandi’s ethic of peace.

What the documentary never does, though, is to actually castigate people who fight. There is no denunciation of warmakers. And without that denunciation, it’s difficult to see the ethical choice for peace as the only ethical choice. The COs are right…but the warmakers aren’t wrong.

I’m sure that this is not the attitude of many of the people interviewed here. George Houser, for example, publicly refused to register for the draft in order to protest the possible U.S. entry into World War II. That was undoubtedly based on his feeling that preparations for war were wrong. But the documentary dwells on his heroism at the expense of the critique — not quite realizing that without the critique, the heroism loses its point.

Theologian Stanley Hauerwas in his book Dispatches from the Front argues that for Christians, non-violence is not an ethic or a theory, but a way of life which is “unintelligible apart from theological and ecclesiological presumptions.” Pacifism doesn’t arise from an inward-turning confrontation with conscience; it comes out of a particular kind of communal faith. He adds, in reference to the first Gulf War

Surely, the saddest aspect of the war for Christians should have been its celebration as a victory and of those who fought it as heroes. No doubt many fought bravely and even heroically, but the orgy of crusading patriotism that this war unleashed surely should have been resisted by Christians. The flags and yellow ribbons on churches are testimony to how little Christians in America realize that our loyalty to God is incompatible with those who would war in the name of an abstract justice. Christians should have recognized that such “justice” is but another form of idolatry to just the degree it asked us to kill. I pray that God will judge us accordingly.

Hauerwas, in short, is able to do exactly what the documentary will not : he is willing to say that if the path of nonviolence is right, and those who follow it are heroes, then the path of violence is wrong, and those who follow it are…at the least, not heroes. His non-violence is not about his personal conscience and what’s right for him. It’s about what’s right for him, and for his community, and for his God, and by extension, for his nation and the world.

Though the documentary has a lot of practical advice on avoiding the draft and obtaining CO status, it’s all offered very much for those who might want it; there’s little in the way of evangelical fervor. Nobody here says, damn it! You…yes you, watching this! It’s your moral duty to become a CO! Which is a shame because, inspiring as many of these personal stories are, if we’re ever going to get to a place where we’re waging, say less than two wars at a time, I think we’re going to need a pacifism with a bit more fight to it.

Just a quick reaction to the (maybe ironic, I’m French so I may have missed it) admission that “All wars are good wars.”

WWII is very specific in the history of wars because there was a real danger, a terrible force invading and annexing all countries around it, with the intention to implement terrifyingly inhuman laws. This is why it has remained such a popular war in pop culture.

Most wars have much less legitimity. WWI is a great example. Austria invades Serbia because the Archduke was killed there by what you’d now call a terrorist. Russia has a historic tie to Yougoslavian countries and declares war on Austria. Russia’s allies, France and Great Britain, do the same. Germany, allied to Austria, declares war to the others. A few more dominos fall and you have a World War that killed a insane number of people for ludicrous reasons.

And of course, all those wars to depose dictators are so hypocritical ! In Lybia, Irak & Afganistan, we destroy planes, tanks and weaponry we sold to them very, very recently.

Nice article, as someone who’s never seen anything written (or filmed) on COs before I loved the suggestions of macho posturing on all sides.

It makes sense to me that you cant see the CO’s heroism without understanding their anti-war ethics, but does the film have to take a stance on that? I mean, if the criticism is that they dont explain the anti-war ethics sufficiently then I suppose thats legitimate, but it seems as if you’re suggesting that only an anti-war film can accurately portray the COs, that the ethics of the film should match the ethics of the subject?

That just strikes a wrong ‘un with me, it just seems to sharpen a dichotomy between those who fought and those who didnt, while what I like most about what you’ve said about the film is the points of macho similarity between all the people involved. I’m not American, I dont really know what PBS is like, but it sounds as it they’ve attempted to take a neutral, middle ground perspective. Maybe they did that badly, but I find that a more laudable journalistic aim than taking a strong, exclusionist stance.

P.S seems a bit odd in that respect to compare the journalism of the film with Hauerwas’ personal ethical statement

The strangest thing here is the revelation that Ed Asner sounds like himself. What are the odds?

Hey Josselin and Ben. Thanks for your comments.

Josselin, I was being ironic. I agree that WWII is a lot more defensible than most wars. My point, though, was that all wars are defended on ethical grounds (pretty much.)

Ben, PBS is the public television station in the U.S. I’m very skeptical of the idea of journalistic objectivity in general. In this case, the film was very supportive of the COs…but tended to emphasize their personal heroism and the importance of conscience rather than a broader ethical stand. So they weren’t being neutral…just (ahem) nonconfrontational.

There’s an article on pacifism during WWII in the new issue of Harpers. It’s by Nicholson Baker, and argues that WWII was in many respects a hostage crisis, and that US intervention escalated the violence and pretty much turned the Holocaust into a foregone conclusion. I couldn’t quite buy into a what at points reads like a causal argument about historical contingency, but I appreciated it for its willingness to think otherwise about “the good war.” In any event, the article is worth reading.

Nice article, with an appropriately gentle jab at “a typical PBS experience. Lots of people are interviewed in front of bookshelves. Lots of period footage rolls by as obtrusive music tells you how to feel…”

The problem with pacifism, as with most “ism”s, is that it offers a “one size fits all” approach to a messy, complicated, ever-mutating world.

As the saying goes, “the perfect is the enemy of the good,” and in the same way those Floridians who voted for Ralph Nader because Kerry wasn’t liberal enough eased the way for George W. to steal the Presidency, a pacifist response to the Nazis and Imperial Japanese would have resulted in those two great evils taking over the world.

Pacifism can be an effective tactic when dealing with an opponent which has a free press, a significant quantity of liberal-minded people. This worked for Gandhi and Martin Luther King.

But when dealing with dictatorships, pacifism only gets its proponents imprisoned or slaughtered.

In this transcript of a TV interview, the Dalai Lama was asked, “Is violence ever justified?”

———————-

No. In theoretically, yes. You can say in certain– under certain circumstances. Provided your motivation is good. Your goal is larger interest for larger people and a just cause. Theoretically, a violent method can be permissible, but in practical level, I feel always better avoid using violence…. In our case, Tibet case, violent method is almost like suicide. Not only against our principle, but also practically. Suicide. No use. …

———————–

http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/24073087/ns/nightly_news/

Alas, pacifism has only meant that instead of being slaughtered outright, Tibetan culture and ways are being squeezed out of existence; swallowed up in the Chinese mass.

The Nader thing happened when Bush was running against Gore, not Kerry. And there’s reason to suspect there was more at work in Florida than Nader… ballots went missing, certain populations were turned away at the polls.

That said, I think you have a good point so far as “isms” are concerned, though it’s important to remember that within any “ism” there’s usually a plurality of views and approaches.

The big question for me w/r/t WWII is whether it’s useful to think in terms of intervention vs. non-intervention, where the latter is the counter-factual that justifies the former. If you take the type and timing of intervention as your counter factual, say an earlier military intervention, aggressive sanctions and less collusion with and fewer birthday cards for Hitler in the years leading up to Pearl Harbor, then the calculus gets more complex.

In terms of the Holocaust as hostage crisis; the reasons ww ii was (and is) justified most directly is not by the holocaust, but by pearl harbor.

In terms of isms…this sort of dovetails with the discussion on the other thread about transcendent truth. For Hauerwas, pacifism is a witness; the expression of faith of a particular christian community. Shifting the ground to questions about what government should or should not do is somewhat besides the point for him; the question is where christians should stand when called upon to support violence. That is, it’s not up to christians to behave as responsible citizens who hold the fate of the world in their hands (following niebuhr) because God holds the fate of the world in his hands. Christians are called on to testify to the corrosive effects of violence, and to stand against the logic that justifies bombs in the name of revenge, or pragmatism.

Tibet is sort of an interesting example. It’s true that the outcome there is bad…but would it be better if there were armed resistance, most likely unsuccessful, resulting in huge bloodletting and slaughter?

Baker doesn’t suggest that the Holocaust was the reason for WWII, just that it’s been retroactively held up as a justification for intervention. His point about it being a hostage crisis was that that’s what it was prior to Pearl Harbor, and that the way to deal with it was to treat as such (i.e. by not denying visa’s to Jews, refusing to supply steel to Hitler.

Of course…there are plenty of pacifists, even in WWII…who are not Christian and who are willing to make impassioned stands for pacifism. Even now (esp. now?), however, there is a widespread glorification of war and violence that is likely to make pacifists a minority…Christian or not. Feminism is another ideology with a strong pacificist tradition. It doesn’t seem to be working though…

Yeah; it’s hard to know what Hauerwas thinks about Gandhi. There’s one offhand remark where he seems to be arguing that Gandhi’s pacifism was instrumental rather than based in a religious commitment…which I’m hoping I misunderstood or am misremembering, because I think that’s really wrong, and kind of insulting.

U.S. refusal to deny visas to Jews in the Holocaust was obviously not ideal.

So one good thing came out of watching A-Team (which is the dumbest fucking movie I’ve seen in quite awhile). B.A. Baracus (the Mr. T character) adopts nonviolence while in prison, which makes his role on the A-Team somewhat contradictory. And this leads to dueling Ghandi quotes:

B.A.’s Ghandi Quote:

“Victory attained by violence is tantamount to a defeat, for it is momentary.”

Hannibal’s Ghandi Quote:

“It is better to be violent, if there is violence in our hearts, than to put on the cloak of nonviolence to cover impotence.”

That sounds pretty great, that they made BA a pacifist. Now I’m tempted to see it….

————————–

Nate says:

The Nader thing happened when Bush was running against Gore, not Kerry…

————————–

Thanks for the correction; this Tim Kreider cartoon gets the credit for my “misremembering”: http://i1123.photobucket.com/albums/l542/Mike_59_Hunter/DipwadVoteMarch24-2004.jpg

————————–

And there’s reason to suspect there was more at work in Florida than Nader… ballots went missing, certain populations were turned away at the polls.

—————————

Indeed, there was a gigantic mass of chicanery going on. But the Naderites sapped enough Gore votes to make the election “stealable,” with the aid of those right-wingers in the Supreme Court who just happened to set aside their strict-constructionism long enough to crown Bush Prez.

—————————

Noah Berlatsky says:

…Tibet is sort of an interesting example. It’s true that the outcome there is bad…but would it be better if there were armed resistance, most likely unsuccessful, resulting in huge bloodletting and slaughter?

—————————

As the Dalai Lama correctly noted in that interview, armed resistance would be suicide for the Tibetans. (Ah, if only Tibet had oil; then the USA would’ve all of a sudden found it a morally compelling cause…)

—————————-

Richard Cook says:

…B.A. Baracus (the Mr. T character) adopts nonviolence while in prison, which makes his role on the A-Team somewhat contradictory…

—————————-

But, surely he doesn’t stay nonviolent, right? The Wikipedia entry on the movies just says he “refuses to kill anyone,” which hardly removes the possibility of non-lethal mayhem.

Am reminded of this film, with its “there are times to set aside pacifism” argument:

—————————–

Sergeant York is a 1941 biographical film about the life of Alvin York, the most-decorated American soldier of World War I….

Alvin York (Gary Cooper), a poor Tennessee hillbilly, is an exceptional marksman, but a ne’er-do-well prone to drinking and fighting…He undergoes a religious awakening…and turns his life around…York vows never to get angry at anyone ever again…

York tries to avoid induction into the Army for World War I as a conscientious objector due to his religious beliefs but gets drafted into the Army nonetheless…

York still wants nothing to do with the Army and killing. Major Buxton, his sympathetic commanding officer, lectures York about history from a U.S. history book. He gives York temporary leave to go home and think about fighting to save lives…

His unit is shipped out to Europe…Pinned down by German fire and seeing his friends being shot down all around him, his self-doubt disappears. Owing to the large number of casualties, York suddenly finds himself the last remaining Non-Commissioned Officer (NCO) and thus placed in charge. He works his way around behind German lines and shoots with such deadly effect that the Germans surrender. Then, York forces a captured German officer…at gunpoint to order the Germans still fighting to surrender. He and the handful of other survivors end up with 132 prisoners. York becomes a national hero and is awarded the Medal of Honor.

York later explains that he did what he did to hasten the end of the war and minimize the killing…

——————————–

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sergeant_York

You’re right Tom, BA eventually abandons strict nonviolence for a wimpy “violence is okay, as long as I don’t have to shoot anyone” rule.

“Violence Lite”?

Um, sorry Mike, I don’t why I called you Tom.

Someone just sent me the link to this piece. I read your essay with interest, and am writing to try to shed some light on some of the issues that you raised.

The phrase The Good War doesn’t really apply to Libya, Vietnam, Bosnia, Iraq, or any other conflict. It only applies to WW II. Why? There is a collective memory from that generation that it was a moment where the country was unified and that that feeling was what made it good. The phrase is not a comment on the morality of war, but on the unity of the country. When Judith Ehrlich and I asked Studs Terkel why he called his book The Good War, he replied that that was not the title. He took out a copy, pointed to the title, and said, “The title is not the good war. It is Quote The Good War Unquote, because no war is good.”

I have never met a pacifist who could be described as macho, or who criticized the soldiers who fought. The COs all felt that their moral decisions were personal ones, and that they did not have the right to impose them on anyone else. If they weren’t willing to “castigate those who fight,” it wasn’t our job as filmmakers to do so. I also have never met anyone who served in the army during World War II who had anything negative to say about conscientious objectors.

On the subject of COs volunteering for dangerous experiments, it seems mean-spirited to attribute their sacrifice to personal pride and societal pressures. I had no reason to disbelieve them when they told me that they were patriots, and willing to risk their own lives, but not willing to take the lives of others. The hepatitis trials contributed to the development of effective vaccines and the starvation experiments helped formulate policies for refugee rehabilitation after the war.

Even though a pacifist at the beginning of the film admitted that when confronted by the menace of Hitler he didn’t have an answer; the majority of World War II conscientious objectors agreed that something had to be done. That is why 25,000 of the 42,000 World War II conscientious objectors served in the army. They were so eager to help on the front lines as medics and ambulance drivers that the army said they couldn’t use all of them. It is clear though, that all who served in the army, including the COs, contributed to the war effort.

Obviously the WW II COs didn’t change the conduct of the war, but they did help transform our society after the war. It was Bayard Rustin, a World War II war resister, who taught Martin Luther King how to use non-violence as a tool for social change, and organized the 1963 March on Washington. WW II COs started the anti-nuclear movement and taught my generation how to fight war during the Vietnam years. Whether you agree with what they did or not, they made a difference.

PS In the interests of full disclosure, I was a conscientious objector during the Vietnam War.

Thanks for your thoughts, Rick. I appreciate you taking the time to come by.