A little while back, Anja Flower wrote about gender identity in Ghost in the Shell. At the conclusion of zir essay, Anja argues that Ghost in the Shell, in its multiple marketing iterations and incoherence, can be read as undermining the idea of an essential gender.

Even laboring under the assumption that Motoko Kusanagi is bound by an underlying essence, we must admit that this binding essence is fictional – that in fact “Essential Motoko” is a construct we amalgamate out of images and ideas accumulated from consuming the Ghost in the Shell franchise in its various forms. Abandoning this idea, we are free to focus on the Major as she in fact is: a series of images and text snippets juxtaposed. Seen this way, gender can be read into just about everything: into the whole book, into whole characters to be sure, but also into scenes, pages, panel sequences, environments, color/tone palettes and individual colors/tones, outfits and items of clothing, poses, facial expressions, speed lines, patterns and symbols, inking techniques, even single lines. The changes in gendered expression from line to line, color to color, face to face, panel to panel are often tiny, but they are important because they provide an entirely different image of gender in comics. This image is not one of an immutable essence limited to characters and rarely or never changing, but as an everpresent jumble of tiny shards of signification, only semi-coherent at best and only even pushed into appearing as constant (if fluid) by the reader’s ability to imagine the gaps in information between panels – the device of “closure” described in Scott McCloud’s Understanding Comics. Gender overgrows in every direction, abundant shards of it popping up wherever the particular reader’s subjectivity allows it; it is subjective, certainly, and also cumulative and temporal, agglutinating and morphing as the reader reads and re-reads, consumes new additions to the franchise, looks at new pieces of fan art, comes to greater understanding of plot points, digests criticism. Each of these experiences provides an abundance of these shards of gendering for the reader to plug into their gender-concept of the entire franchise, the individual story or character, the individual page. The reader is selective in doing this, and the shards from which they select appear different as the reader acquires different sets of eyes.

I hadn’t ever read Ghost in the Shell, but Anja’s essay intrigured me. My wife happened to have bought the manga, so I thought I’d read it and see what I thought.

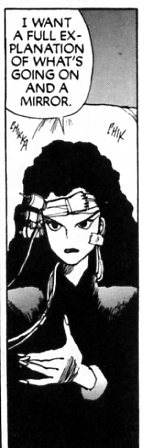

And what I thought was…well, to be honest, I kind of felt weird thinking anything about it. Here’s an example of why.

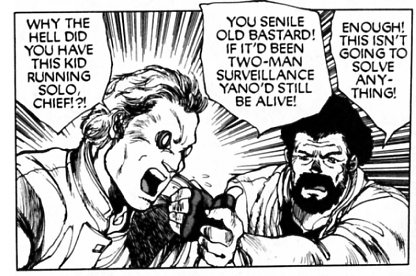

And here’s another:

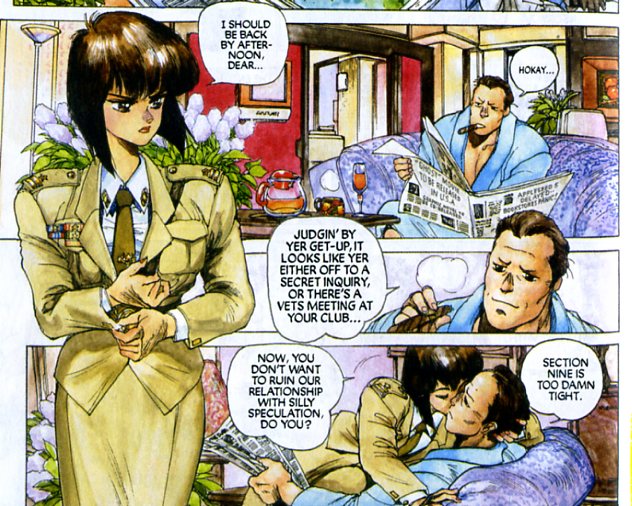

Or here’s one more:

Just looking at those panels, you might conclude that they were utterly anonymous genre fodder. The crusty but tough team leader fulminating hard-assedly; the ultra-competent fighter grieving through bluster hard-assedly; the sexy-tough couple bantering sexily but hard-assedly. You might think that there is nothing going on in this manga that you haven’t seen before; that character, plot, and atmosphere are little more than a half-hearted scrambling of tediously familiar topes.

You might think that. And you would, in fact, be right. Ghost in the Shell is, from beginning to end, an uninspired, barely stirred sludge of half-digested clichés. The plot is complicated, twisting, and aggressively irrelevant, bearing the characters along in a rush of technobabble from one uninvolving violent set-piece to another. The hyper-competent Major Motoko Kusanagi is a medical miracle, managing to fight, wise-crack, switch brains, and flash cheesecake without ever acquiring even the hint of a discernible idiosyncratic personality. When the mysterious, artificially generated Puppeteer merges with Kusanagi’s consciousness at the end of the volume, you wonder how on earth anyone is supposed to tell the difference. I guess Puppeteer/Kusanagi makes more speeches than Kusanagi alone did? That’s something I guess.

Kusanagi/Puppeteer — Still talking tough, still saying nothing.

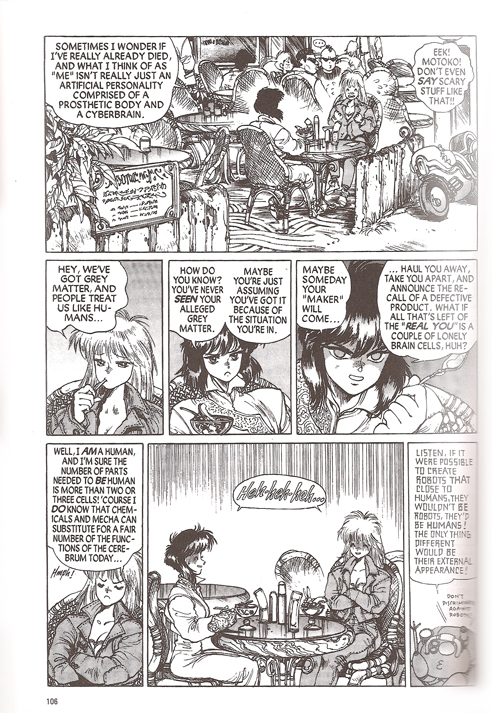

The thing is, the fact that Ghost in the Shell is kind of lousy doesn’t necessarily undermine the points Anja makes. In fact, it’s lameness can in some ways be seen as thematic. The book, as Anja notes, is about the fracturing and fluidity of human identity; the characters are a mix of human, robot, cyborg, and combinations thereof. The page below from the manga (reprinted by Anja) lays out the theme — how can you tell whether you’re human or not? What does it mean to be human, anyway?

“what if all that’s left of the real you is a couple of lonely brain cells, huh?” Kusanagi asks.

The irony is that there aren’t even a couple of lonely brain cells here. No brain activity at all appears to have been expended on creating these characters. They speak and interact, but they have no real history or personality; they’re just sci-fi cyberpunk cyphers, mechanically running through their tropes. They wonder whether they’re real in the most artificial manner possible. Are they pasteboard cliches dreaming that they’re robots, or robots dreaming that they’re pasteboard cliches?

Genre’s inherent emptiness can often be an excellent way to look at the way the world doesn’t work. This happens in Gantz, where the incoherence of the genre elements fits into a supposedly cynical, but arguably terrified nihilism. It happens in Moto Hagio’s story A Drunken Dream, where the standard narrative warps and fractures before an underlying trauma.

For Anja, I think something analogous happens with Ghost in the Shell. The fact that Kusanagi is a blank slate emphasizes the narrative’s half-denied intimations of open identities. The book claims that inside every body, of whatever sort, there is a ghost or essence. But despite this, Kusanagi is, for practical purposes, no one — the Puppeteer takes over an empty puppet. The self is not a fixed core nailed to a single gender; it’s a series of shards that come together in this way and that. For Anja, that lack of essence is (at least potentially) freeing.

For me, though — I mostly find the implications of Ghost in the Shell depressing. I don’t have anything in principle against fluid identities…but in Ghost in the Shell, those fluid identities seem to be not so much liberating as claustrophobic. You can be anyone you want…as long as the person you want to be is a stereotypical tough-talking government agent, scrambling blandly through some bone-headed plot. To give up your essence in this context doesn’t open up infinite possibilities. It just makes you generic. Abandoning your self doesn’t let you escape social conventions and expectations; on the contrary, it means you have no choice but to embody them.

You have to watch the movie and TV series. Especially the movie. From wikipedia: “The film adaptation presents the story’s themes in a more serious, atmospheric and slow-paced manner than the manga.” You should at least watch the film’s opening sequence. Major Kusinagi uses her nude body as a weapon, but NOT a sexual weapon – as a functional piece of machinery. She doesn’t flirt. The guys in her division don’t hit on her. The character is still a cipher in some ways, but the movie actually explores what that means. Major Kusinagi, even while being all-business-all-the-time, still manages to have a personality, if only through her interactions with others, and the expectations they project onto her.

Also, it’s set in Hong Kong, which my friend from Hong Kong likes to say is the ACTUAL city of the future, not Tokyo, which has a lot of crumbling older infrastructure.

I’d like to point out that “parts of my brain are synthetic! What if I’m not reeeeeeeeeeal” is an extremely normative concern to voice. You’re assuming that the default is an able-bodied, all-original-parts-in-working-order human being and that it’s wrong to alter the body in ways that improve functionality. I don’t explain it very well, but lightreads has a take-down of this attitude here.

The movie takes a very different approach. Major Kusinagi is different, but she is effective, and the people around her adapt to her difference and in some ways assume she is more like them than she really is. There’s tension in the Puppet Master storyline because Kusinagi and the Puppet Master are similar, but the Puppet Master is the villain. But is he/she really a villain? Is difference automatically bad? Etc.

So yeah, you should watch the movie. With subtitles, preferably, since the technobabble is way less annoying to read than to listen to (such is my opinion at least). The movie is also much more visually interesting than the manga, a the visuals do a lot more of the thematic heavy lifting.

Noah, I agree with everything you say here, but while I haven’t seen the movie in about a decade my recollection is that it uses the comic as little more than a jumping-off point. I’m not the movie’s biggest fan, but I enjoyed some of the eye candy. Director Oshii is kind of an otaku Antonioni; if that sounds godawful then you might wanna give the film a pass, but at the very least it demonstrates one approach to reworking dry nerdy source material into something idiosyncratic.

The movie is a real chore to get through, but I recommend getting the score. It’s really good.

the movie is basically three episodes each with a conspiracy plot, action scene and disconnected philosophical monologue (pretty similar to the comic, actually), and with a long passage of staring at pictures of decaying buildings, rain, mannequins and soulful dogs, with some interesting music. the main thing it adds over the book (other than, as subdee says the urban Chinese setting) is that it looks more arty and tactile, and the fan-service is a little weirder (still lots of guns and tits, but now everyone has a sort of corpse-ish waxiness rather than being perky and super-kawaii). you might like it better than the manga. I didn’t get that much out of either.

I’ve always preferred Shirow’s earlier series Appleseed, which he unfortunately left unfinished. Though perhaps my preference is nostalgic since it was one of the first manga series I read. Ghost in the Shell seems so cold and too invested in the technobabble. Appleseed felt more human.

The two movies are better than the comic and the two TV series are better than the movies.

None of the versions says anything much that hadn’t already been said better by cyberpunk novelists but I found the TV show to be quite entertaining despite generally having a pretty low tolerance for anime series.

I’ve read most of Shirow’s works and the only one I don’t regret wasting time on is Dominion, which is much lighter (and funnier) than anything else of his that’s come out in English.

I did see the film many years ago…I have basically not memory or impression of it though, so looking at it again might be worth a shot….

I wasn’t impressed with the film when I saw it a few years ago. Kusanagi was such a blank slate, it didn’t seem like such a big deal when she merged with the Puppeteer. Add two nonexistent personalities together, and you still get nothing.

Animation was pretty good though.

Got it, Anja says gender identity is liberated in Ghost in the Shell when a woman can act like a man and you say that such a hard ass character is nothing more than a trope. It would be interesting to see if a more appealing character is possible that doesn’t fit into the mold of preconceived stereotypes.

Incidentally, I don’t like the comic very much at all. It *is* basically cyberpunk violence porn featuring a fairly obvious masturbation-fodder badass woman character. She’s built to relatively idiosyncratic specifications, which I enjoy, but she’s still just a relatively unusual version of an archetype that in the end is more or less just hetero-male-gaze wank-fodder. She’s yet another woman who’s badass because her straight male creators and (presumed) audience find badassedness hot – like the tough women of a women-in-prison or rape-revenge film. Not to say that I hate the porniness of it – I do enjoy applying my own queer gaze to Shirow and company’s sexy-tough-woman creation. Her ultimate status as a fetish object, though, is one of the many ways in which Ghost is ultimately reactionary. It sees the fluid and fractured quality of identity becoming more and more apparent, and tries to reassert an essentialist framework; it sees women stepping outside of traditionally gendered roles and claiming space for themselves, and tries to reclaim male control by sexually fetishizing the new (post?-)woman for a hetero male gaze. What Ghost is doing feels a bit like the capitalist habit of gobbling, packaging and selling subcultures (hippie, punk, goth, grunge, you name it). Resist capitalism – purchase a Capitalist Casualties shirt at your local Hot Topic!

I’m not sure, in the end, that Ghost succeeds in its reactionary project, or that it could do so without killing itself. Ghost is a dialectic: essence and anti-essence. Kusanagi is a battleground for that conflict, and of course as a good queer radical I want the forces of anti-essence to win out. The franchise’s identity conflict *is* its identity. That’s how we get all this stuff that feels a lot like queerish, feminist-ish cyber post-identity politics (even a cameo by Donna Haraway!) in a franchise that posits the existence of human souls.

That’s how we end up with a weird, beguiling mess of a character like the Major, right? She’s either an anti-essence trying to be an essence, or an essence trying to be an anti-essence: a cliched archetype, but not, but yeah then again maybe she really is… The Ghost creators want an anti-essence to fetishize, but heterosexist fetishization is nothing if not an essentialist project, so they end up building up an essence-trope-thing to do a strip-tease for them. She flashes enough queer post-identity wildness to keep them beguiled and excited, but not so much that they feel themselves getting sucked into the polymorphous perversity of a queerness from which their heteronormativity might not be able to recover. Is she really essence or anti-essence inside that shell? Is the queerness a sexy piece of lingerie, or is the hetnorm fetish object thing just a disguise? Who knows?

I was arguing that gendering in comics in general, not just in Ghost, is only pretending to be essential – the “every speed line, every color” bit. That *is* true. I certainly don’ think that it’s true for the characters in the story, though.

Aren’t fluid (post-)identities kind of definitionally non-trope? They can spend time in trope spaces, sure, but there’s so much space outside of the tropes that they’re unlikely to spend all their time simply jumping from trope to trope. I don’t think that’s generally how such things work.

So yeah, the Ghost manga sucks. Everything I find interesting about Ghost is better articulated in the rest of the franchise than in the manga – and Shirow does better at his tough-cop-woman superbabe routine, and his sci fi themes generally, in Appleseed than in Ghost.

Shirow is quite into his essences and souls, incidentally – in the extensive notes he likes to write for his manga and various world-building and book projects, he returns repeatedly to theological and supernatural subjects, including his belief in (the possibility, at least, of) ESP.

Noah, I guess you could say that my love for Ghost in the Shell is a bit like your love for Wonder Woman?

Whoa, that was quite a post. Sorry about that.

It was probably ill-timed, too, given that it was written as a way of procrastinating on an art deadline. :-/

So yeah, I wrote this big post and now people will probably respond and I won’t have time to engage in discussion, but I’ll really want to, which is bad because I’ve got to be drawing, and arrgggh. =_=

Hey Anja. Thanks for the extended reply!

I don’t think my interest in the Marston/Peter WW is quite the same as your interest in Ghost in the Shell. In the first place, from what you say here, I like Marston/Peter a *lot* more than you like GIS. For another, Marston’s feminism and queer-positivity are a lot more conscious, clear-cut, and avowed, I think.

“Aren’t fluid (post-)identities kind of definitionally non-trope?”

I’m iffy on this. I think the gay/queer utopia is itself familiar enough at this point to possibly be its own trope in some circumstances….

Noah,

Could you clarify what you mean by Ghost in the Shell being cliche ridden? The work is almost 30 years old. Many people have stolen from it over the years. Are you taking it’s age into consideration?

I think I am? Hard-boiled detective/spy nonsense is pretty old. It’s action/adventure cliches in a cyberpunk setting…and even cyberpunk preceded GIS, I’m pretty sure.

Okay, I see what you’re saying.

While cyberpunk preceded GitS, I feel Shirow really explored the implications of technology and the way it could reshape our lives in new ways. I would argue he predicted the internet and its ubiquitous presence in our daily life.

Granted, Shirow isn’t the best storyteller. There’s lots of techno and political babble. But he’s a genius world builder. He asks a lot of philosophical questions about the relationship between humanity and technology and how each form and change the other. There’s a reason Production IG keeps coming back to GitS. That well won’t run drive for a long time.

Yeah; he just strikes me as really obvious and dunder-headed on those issues compared to Philip K. Dick or Samuel Delany or any number of other sci-fi writers. And the failure of characterization and plot are real failures that undermine the ideas he’s trying to get across. IMO.

Noah,

Fair enough. I still find it a thought provoking work. This was my first “anti-Pinocchio’ story where no wants to be human. That probably taints my opinion.

For all the people recommended the movie and TV series, I’m quite sure Noah would still hate them. The kind of genre stuff that aspires to be bigger what it actually is–I think that’s still evident in the movie and TV series, and would probably turn him off. It also helps that they have a decent critical following, which probably adds fuel to the fire. ;)

I haven’t given a decent reading of the manga yet. I liked the anime TV series, was lukewarm on the first movie, and surprisingly enjoyed the second movie, but I feel like those are the type of anime Noah would hate, based on my assessment of them above. ;)