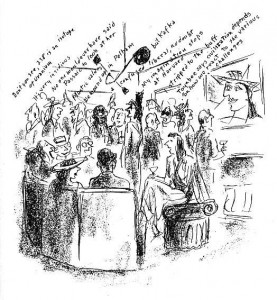

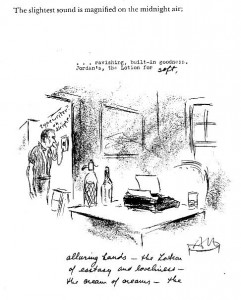

East of Fifth by Alan Dunn

Fredrik Strömberg wrote Black Images in the Comics (Fantagraphics Books, 2003). In the foreword of said book Charles Johnson stated:

[…] while the cartoonist and comics scholar in me coolly and objectively appreciated the impressive archeology of images assembled in Black Images in the Comics, as a black American reader my visceral reaction to this barrage of racist drawings from the 1840s to the 1940s was revulsion and a profound sadness.

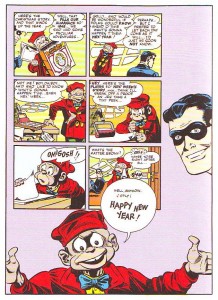

Jumping to page 86 we can find the inevitable Ebony White (the family name has to be a joke) accompanied by Will Eisner’s (the character’s creator) comment:

I realize that Ebony was a stereotype because I drew him in caricature – but how else could I have treated a black boy in that era, at that time?

Well… Eisner could have asked East of Fifth ‘s author Alan Dunn

Title page of East of Fifth.

“Will Eisner’s Almanack of the Year” [December 26, 1948] as published in DC Comics’ Will Eisner’s Spirit Archives Vol. 17 (July 4 to December 26 1948), 2005.

As you can see above both “Will Eisner’s Almanack of the Year” and East of Fifth were published in 1948. Sacred cow defenders usually utter the same excuse that Will Eisner used above. Basically: he’s not to blame, he lived in less enlightened times, etc… On the other hand the Eisner (or McCay or Barks, etc…) critics say something like: that’s true, nevertheless other creators didn’t fall into the trap of racist imagery. The latter’s problem is that they never give any example… Until now: clearly belonging to the second group I believe that great art gives us a complex view of the world, hence: it has no place whatsoever for the simplistic and offensive imagery of racists. See below how Alan Dunn portrayed black people in East of Fifth and compare the depiction with Will Eisner’s pickaninny.

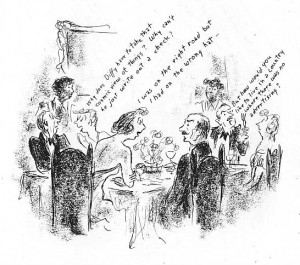

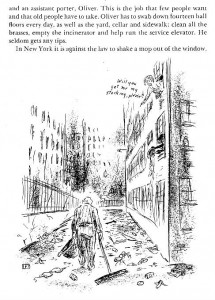

East of Fifth, page 95.

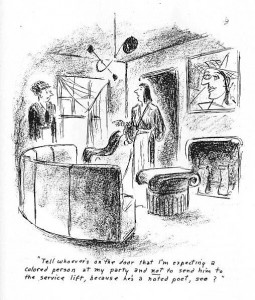

As we can see above, it’s not that difficult. Alan Dunn just needed to caricature black people in the same way as he caricatured everybody else. What he couldn’t change was black people’s role in society. In this image, as housemaids in a party. Even so, he didn’t resort to job stereotyping either. In the second image below the fourth character in the background row (counting from the left) is a middle class black person (a poet) attending a white people’s party. In this sequence racism is clearly viewed as embedded in 1940s society (also: on page 92 an employee says: “Cab for Mrs. Eelpuss – white driver”). (Even if they appear here together the two images are 30 pages apart. Braiding is the formal device that links East of Fifth the most with comics. The book is also an example of what I call a locus .)

East of Fifth, page 59.

East of Fifth, page 89.

Some cartoonists praise stereotypes because, according to them, it’s an immediate way of conveying ideas. Looking at the image above I can see why: not that it really matters, of course, but without the usual short cuts (and forgetting page 59) it’s not immediately obvious that the gentleman depicted is indeed black. My question is: is this offensive immediacy really worth it? I don’t believe that Will Eisner was a racist. As Robert Crumb famously put it on the backcover of his comic book Despair (1970): “It’s just lines on paper, folks!” (before that Crumb depicted a character named Nutsboy tearing apart a woman and saying “it’s only a comic book, so I can do anything I want” – see below).

Robert Crumb, “Nutsboy”, Bogeyman # 2, 1969, as published in The Complete Crumb Comics # 5, Fantagraphics Books, July 1990.

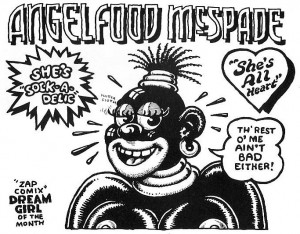

I’m not denying Robert Crumb or any other artist, for that matter, the right to draw “anything [s/he/they] want,” but drawings have consequences as we have seen at the beginning of this post. In the story “Angelfood McSpade” (see below) Robert Crumb shows his camp tendencies exploiting a racist imagery that, I suppose, Crumb sees as his cultural trash heritage. As I see it Angelfood is marijuana (the character is an allegory), but that’s irrelevant for this post. The point is that kitsch or no kitsch, camp or no camp, it’s a racist depiction and I can’t decide who to blame more: Will Eisner who uncritically swallowed his times’ imagery or Robert Crumb who reveled in it.

“Angelfood McSpade”, Zap # 2, June 1968, as published in The Complete Crumb Comics # 5, Fantagraphics Books, July 1990.

John Crosby (1912 – 1991) was a media critic. In one of those happy circumstances that happen once in a blue moon one of his columns “Radio in Review” fell in my hands. It was published in the New York Herald Tribune (July, 1948) and it’s about East of Fifth. Sharp as a knife Crosby understood (with Göethe, looking at Töpffer’s drawings, many years before) that this book had an unnamed form: the graphic novel. Here’s what he said in his column “Radio in Review: East of Fifth, West of Superman” (New York Herald Tribune, July, 1948):

[…] “East of Fifth,” by Alan Dunn, a cartoonist who is also a subtle and polished writer, is the story of twenty-four hours in the life of a large, fashionable Manhattan apartment house and, of course, of its occupants, told in cartoons with an accompanying text.

I bring it up here because Mr. Dunn’s book may well be a brand new art form, a sort of sophisticated, literate extension of the comic books, rather horrifying in its implications to writers unable to draw. This isn’t the first book in which cartoons and text tell a complete story but, to my knowledge, it’s the first time anyone has attempted serious literature in this field. In this unreading age, when all the arts and much of journalism tend towards pictures, Mr. Dunn’s comic book for adults is certainly significant, just a little distressing and thoroughly captivating.

Alan Dunn juggled with three forms: literature, comics, but above all, cartoons (he was a New Yorker cartoonist). While printed words carry the load of the narrative cartoons are lively comments on the little events that occur in the building (see below).

Alan Dunn was an architecture cartoonist. He was as interested in the machinery of the building and the personnel running things as in bourgeois life inside it. The tone is a bit too breezy (it reminds Ben Katchor’s cool and detached, if poetical, remarks, sometimes). A suicide occurs, in a masterful ellipse, nevertheless. It barely disrupts the hustle and bustle of city life though… and, maybe, that’s the whole point: the book ends with a drawing and a phrase alluding to “the cold metropolis of the north.”

East of Fifth, page 38.

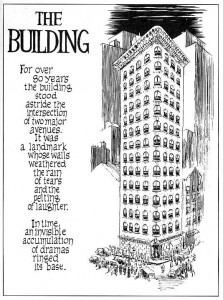

Going back to Will Eisner it seems to me that, at least in the 1970s, he was influenced by Alan Dunn’s work. It’s a shame that, by then, it was too late to avoid Ebony…

East of Fifth, page 5.

Will Eisner, The Building, Kitchen Sink, 1987, as published in The Will Eisner Companion by N. C. Christopher Crouch and Stephen Weiner, DC Comics, 2004.

I end this post with page 134 of East of Fifth. It’s now the wee hours and someone complained about the noise of a character’s typewriter. He then switches to handwriting in a great visual device that will be used, years later, by Charles Schulz.

East of Fifth, page 134.

__________

Update by Noah: This post inspired a roundtable on R. Crumb and race, all of which can be read here.

Coming up next on the Hooded Utilitarian, Domingos Isabelinho explains that Jonathan Swift was a monster who wanted to eat Irish babies, that Orwell loved Big Brother, and that Mark Twain thought that Huckleberry Finn was going to Hell for trying to free Jim from slavery.

Hey Jeet. Crumb’s relationship to his racist iconography is a lot less clear than Swift’s position in A Modest Proposal. Swift’s clearly writing out of rage at injustice and suffering. Crumb seems more to just want to shock or to play with funny/outrageous imagery. That especially seems the case because he will occasionally use blackface iconography in contexts where it isn’t satirical (as on the Janis Joplin album cover he did.)

Sort of going along with that…Swift, Orwell, and Twain were all artists who cared very much about ideas, and who had very thoughtful social critiques. Crumb’s much more of a from-the-hip, instinctual artist. His use of outrageous subject matter is much less controlled than Swift’s. His political subject matter is much less fully developed than Twain’s or Orwell’s.

I think Crumb’s also considerably less of an artist than any of those folks, and the reason why is not unrelated to his lack of thoughtfulness and his ambivalent relationship to his own sexism and racism. But I presume you disagree with that as well….

Anyone who can’t see the satirical (indeed outlandishly satirical) element of Angelfood McSpade has no business being a comics critic. And the use of racial stereotypes on the cover to Joplin’s Cheap Thrills album makes sense: the history of American popular music is deeply permeated by blackface, minstrelsy, and whites appropriating (and parodying) African-American musical stylings (as Joplin herself did). I think it is to Crumb is willing to implicate himself in his satires on racism — that he doesn’t see racism as cultural phenomenon outside of himself that needs to be condemned but as cultural legacies that pervasively shape his own sensibility and need to be confronted internally. Crumb’s delving into racism is a mark of his greatness as an artist. Crumb’s sexism is a more complicated matter for another discussion.

Another point: I appreciate what Domingos Isabelinho is saying about Alan Dunn but I don’t think that the stylistic choices an artists makes can be divorced from history. Dunn was working in the late 1940s, when images like Ebony White (although starting to be criticized) were still common place. So Dunn’s respectful depictions of African-Americans was a progressive act in the 1940s context. Crumb started drawing his blackface images in the late 1960s when American culture was trying to whitewash its racist past by supressing even the memory of those images: Crumb’s act of reviving those images was radical in that context: it was reminding people of a horrible history that they were too quickly trying to repress (in the name of moving on). A lack of historical consciousness is the bigget problem with this discussion.

Sorry, that should be “I think it is to Crumb’s credit that he is willing to implicate himself in his satires on racism — that he doesn’t see racism as cultural phenomenon outside of himself that needs to be condemned but as cultural legacies that pervasively shape his own sensibility and need to be confronted internally.”

A literal minded inability to understand satire and irony is fatal to the task of criticism.

For the record, I acknowledged Crumb’s comics as camp. If you don’t believe me read what I wrote (and I say “read” instead of “reread” for a reason). But I’ll let someone else answer for me. Here’s what Trina Robbins has to say (and sorry for the crosspost – I asked for Trina’s permission, in case you’re wondering…):

“I think most of us have racist and sexist views left over from our cultural backgrounds (I know that *I* do), but we recognize them for what they are and try not to disseminate them. Personally, I have too often heard outrageous misogyny in underground comics dismissed as parody. As far as I’m concerned, rape isn’t funny, torture isn’t funny, depicting black people as gorillas isn’t funny. Maybe one way of thinking of it is, if it hurts people it shouldn’t be simply dismissed as harmless parody, but at least should be explored and questioned. We no longer accept bullying in schools (and a common bully’s excuse is that they were just kidding), should we accept it in comics?”

Jeet, you’re so funny. Everything’s always “if you think this, you shouldn’t be a comics critic!” Because comics critic is such an exalted status that having a gatekeeper puff himself up and draw lines in the sand is supposed to make us all genuflect? Come on, now. Are you bravely defending freedom of speech or are you punctiliously shutting down dissident voices for the greater glory of the ivory tower? Shouldn’t you pick one or the other, at least in the context of a single comment?

“And the use of racial stereotypes on the cover to Joplin’s Cheap Thrills album makes sense: the history of American popular music is deeply permeated by blackface, minstrelsy, and whites appropriating (and parodying) African-American musical stylings (as Joplin herself did)”

So because there’s a history of white appropriation and racist caricature, it makes sense for Crumb to continue the tradition of racist caricature? In the name of what is he continuing it exactly? Is he criticizing it? How so, exactly? Or is he just putting himself in that tradition because he thinks minstrelsy and racist blackface caricature is kind of cool and he wants to be associated with it? If the latter, how is that not simply participating in racism because you think it’s kind of cool? Surely just using racist images isn’t a courageous thumb in the eye of complacent, race-blind America anymore than using rape images is a courageous thumb in the eye of complacent, PC America. If you use racist images because there’s a tradition of racist images and you like that tradition…then you’re perpetuating a racist tradition. If you think there’s something more going on on that Joplin cover, please explicate, but right now it just looks like you’re saying, well, it makes sense because other people did it in the past. And it does make sense — I know why Crumb did it. But just because his reasons are explicable doesn’t make them un-racist.

Someone like Kara Walker is clearly using racist images to critique them. So’s Spike Lee in Bamboozled. Crumb…it’s just really, really not clear, especially if you look at the range of ways in which he’s treated black people in his work. Crumb’s racism is like his misogyny — it’s ambivalently critiqued, embraced, and sometimes fetishized as a sign of his daringness and honesty.

The problem here is not a lack of historical consciousness. It’s fan worship.

I think Swift, Orwell, and Mark Twain would NEVER have said “It’s only lines on paper,” because they didn’t believe that.

@Domingos Isabelinho. “Camp” is not the same thing as satire. Camp is largely apolitical and implies a kind of indulgent affection for older styles. That’s why it makes sense to describe the 1960s Batman show as “campy”. Satire, by contrast, has a political point to it. Crumb’s blackface images take a once-pervasive-but-now-taboo style and not only revives it, but intensifies it to the point that it becomes uncomfortable. The point being that America has a hideous racial history which still shapes the present but which has been suppressed from memory. In the case of the Joplin cover, Crumb was making the very obvious point that the white-person-sings-the-blues music of Joplin is part of this non-denied racial history. It’s a very powerful and shocking cover for that reason, that it contains a pointed critique of Joplin.

@Noah. My point that “Anyone who can’t see the satirical (indeed outlandishly satirical) element of Angelfood McSpade has no business being a comics critic” wasn’t meant to set up gatekeeping rules but was a mildly ironic comment about the fact that it doesn’t take much cultural sophistication to be a comics critic, but the Hooded Utilitarian crew still can’t manage even the few rudimentary reading skills required.

To see what I mean by a lack of historical consciousness, consider this passage from Noah: “Surely just using racist images isn’t a courageous thumb in the eye of complacent, race-blind America anymore than using rape images is a courageous thumb in the eye of complacent, PC America.” Noah is here using the language of 2011 (“complacent, race-blind America” PC). But I was trying to situate Angelfood McSpade in the context of the late 1960s, when America wasn’t complacent, race-blind or PC but rather a racist society experiencing massive racial turmoil but in historical denial about the roots of its racial problems. That’s the America Crumb was addressing with his art. I myself would never use the term PC, unless perhaps ironically, because I think it carries with it the odour of right-wing propaganda.

Intentions matter in art. When a Tea Party cartoonist draws Obama as ape, that’s clearly a racist use of freighted imagery. What Crumb’s doing in his racially-themed strips (which are in any case drawn in a variety of styles) is radically different from that in terms of intent and effect. To not see the difference of intent and interpretive richness is to miss what’s going on.

@Trina Robbins. Well, if Swift and company had to consistently deal with a segment of the readership consistently misunderstanding their art, then maybe they would have fallen back to saying that “it’s only lines on paper”. And in fact didn’t Twain fall back into the role of a performing clown (complete with fancy white suit and southern drawl) whenever people challenged him on the politics of his work?

But actually, since you’ve joined the conversation, I’ll expand what I hinted at before about the difference between Crumb’s alleged racism and his genuine sexism. Trina Robbins, as people should know, has often and eloquently decried the often violent sexism in Crumbs work. I agree with the thrust of this critique, differing perhaps in a few details about how I interpret some stories. But there is a crucial difference between Crumb’s racial imagery (which parodies a once-pervasive style) and his sexism, which manifests itself in a highly personal animosity in the way women are constantly humiliated. There is a small element of self-reflection and self-criticism in some of the sexist stuff, but all too often Crumb indulging in sexist attitudes rather than placing them under critical scrutiny. That’s a crucial difference. (I should add that even the sexist stuff becomes more complicated if one looks at his art from the late 1970s onwards, rather than just focusing on the late 1960s and early 1970s material).

Crumb’s a very complicated artist. His work over many decades has an interpretive richness which demands careful reading – among cartoonists there are only a handful of figures of comparable complexity (Herriman, Gilbert Hernandez, Lynda Barry). To airily dismiss his work is to diminish your experience of comics.

Jeet, I think I’m going to stop insulting you. It’s fun, but I think there are pretty interesting issues here, and I’d rather focus on those at least for the moment (maybe I’ll get back to the troll-battle if you take another swing at me!)

Okay, so first, the Joplin cover. It is possible to see it as a sneer at Joplin. The problem is, it’s equally possible to see it as Domingos says — as a nostalgic use of blackface caricature that is intended not to undermine Joplin, but to humorously confirm her “black” roots. That it’s the second, not the first, is strongly suggested to me by the fact that he uses another blackface caricature elsewhere on the page.

Be that as it may — part of the issue here comes down to this:

“Crumb’s blackface images take a once-pervasive-but-now-taboo style and not only revives it, but intensifies it to the point that it becomes uncomfortable.”

First, it’s worth questioning how taboo blackface caricature was in 60s. Surely it was taboo in some of the circles Crumb moved in. I bet it was not taboo in many communities, however. As Jeet says, overt racism was still widely accepted in many places in the ’60s. I bet there were many people throughout the U.S. who wouldn’t even have blinked at Crumb’s drawing. (And, indeed, I don’t believe that cover caused any particular controversy. It’s widely considered one of the greatest album covers of all time, but I haven’t seen any reports of anger or protests over the imagery at the time — which there should have been if Crumb was actually violating taboos.)

More importantly, it’s worth pointing out that on the Joplin cover, the blackface caricatures are not intensified in any way that I can see. Is Crumb’s drawing more reprehensible than McCay’s Imp? Than Eisner’s Ebony White? It doesn’t seem so to me. In fact, it’s not clear to me that even Angelfood McSpade is more intensely racist than McCay’s mute, animalistic Jungle Imp. I mean, the Imp is really, really, really racist.

And I think that shows up a real problem with Crumb’s method of trying to deal with racist imagery. Racism is not realistic. It’s not something that is grounded at all in any kind of actual fact. As a result, there is no reductio ad absurdum of racist iconography. Racism does not have a point to which you can intensify it and make it ridiculous. Crumb isn’t going to be more intense than the Holocaust. He’s not going to be more intense than generations of slavery. It’s really not clear that he can even be more intense than Winsor McCay’s Imp. Racism and racist imagery— these are not things you can parody just by exaggerating them. They’re extremely exaggerated already, and always eager to be more so. You make it more exaggerated, you just make it more racist. You don’t undercut it.

In that sense, racists who have embraced some of Crumb’s imagery aren’t confused; they’re not stupidly getting it wrong. They’re reacting instead to a failure of his art. Even when his intentions are definitely anti-racist, he hasn’t thought through the issue of racism, or the use of racist iconography, sufficiently for him to communicate those intentions effectively. He isn’t smart about the way racism, or racist imagery works. As a result, he often duplicates the thing that he is (arguably) attempting to critique.

I think it is instructive to look at writers like Faulkner or Crane, or someone like Spike Lee or Aaron McGruder, all of whom confront racism not by intensifying it, but rather by really carefully thinking through how racist tropes work, and demonstrating not only how they diverge from reality, but also how they *affect* and distort reality. There’s a lot of work and thought and genius in dealing effectively with those issues, and I’m not saying I love all those artists all the time, or even that they’re all always anti-racist (Faulkner was avowedly racist at times). But they all seem just a ton more thoughtful, and a ton more committed to understanding how race works, than Crumb does. To me, Crumb (on the most charitable reading) really seems to just hope that throwing unpleasant racial iconography at the wall will somehow be a critique of that iconography.

So, to your historical argument — I don’t think there’s ever been a point in American history where reproducing racist iconography was either especially brave or especially likely to contribute to anti-racism. Crumb’s satire (when it is satire) is neither subtle nor thoughtful…and as a result, his motives and intentions really do come into question. If he’s not willing to think through these issues, why the attraction to the racist iconography in the first place? Does he really want to talk about racism? Or does he just want to reproduce the iconography because he likes it? The way he obsesses over the authenticity of black people in his blues biographies, for example, just makes those questions more pointed. He’s clearly got a fascination with the black culture of the early 20th century — but that can sometimes bleed into a fetishization and even a nostalgia for the oppression of black people.

So…yes, intentions matter. But avowed intentions aren’t the only intentions, and execution matters a lot too. It just seems to me that Crumb’s relationship to racism is a lot more complicated than you’re acknowledging.

Jeet,

I agree that the A.S. strip is satire, but I don’t think it’s very good as satire, and I think it fails in large part because of Crumb’s sexism. Whatever critical edge it might have had is blunted by the fact that the main character is so typical of the women Crumb portrays in his strips. The gestures toward social critique and race relations basically look like set dressing for a self-indulgent romp.

Note that I think Crumb’s satirical intentions could very well have been pure. But I don’t think it’s boneheaded to argue that he missed his mark, and created camp instead.

Further along the lines I was discussing above…I just googled Angelfood McSpade. One of the first sites that came up (I am not linking there) is what appears to be a vicious, avowedly racist site which used the image because it fit with their general sense of humor (and no, I’m not providing any other examples of that sense of humor either). Again, even though such a use was not Crumb’s intent, I think it’s a failure of his art and of his imagination that his supposedly anti-racist work can be so seamlessly co-opted.

Jeet what in the hell are you talking about. Crumb’s use of racist caricatre is…zzzzzfuck dude, I’m half asleep. Maybe you have no business being a comic critic and cultural analyst, ever think about that?

Black power, goddamnit. Fuck Crumb.

Also: I have a pitchfork and a noose for every jerk who casts aside obvious racism in order to say “the REAL problem is sexism/misogyny.”

Fuck you.

Black people can see right through your compassionlessness when you say that. Why can’t we say that Crumb’s misogyny AND racism is problematic?

Why do you feel compelled to change the subject from the scary “racism,” topic to the more palpable sexism topic? Black people in general have seen the anti-racism movement drowned out and co-opted by uncomfortable people for decades. It’s scary to talk about racism if you are white, I know; there’s the danger of self-implication. But everybody is a woman or has a mom. Much easier to get behind. But damn that. YOU //WILL// TALK ABOUT RACISM, no weaseling out of it!

First of all I must say that I don’t know if I can answer to Jeet’s objections being incompetent and all… Secondly it’s very interesting that Jeet, from the top of his towering reading skills and in all seriousness, denies me the right to be a comics critic to add later that he was being “mildly ironic.” Maybe he’s as good an ironist as Robert Crumb is a satirist… who knows?…

Camp and satire may not be the exact same thing (two different words being out there and all…), but both imply (or some camp does) the same kind of detachment, the same irony. And, you know what? When Crumb drew Angelfood McSpade he didn’t caricature Lyndon Johnson or whoever. It’s you who ahistorically and retrospectively view Crumb’s wench as political. But everything is political in the broad sense that you call Angelfood McSpade political. So, no camp can really escape that, right?…

It’s also interesting that you didn’t address one of Trina Robbins’ points above. Not one! Maybe you should be a bit more careful the next time that you feel the urge to throw the incompetent stigma so liberally at anyone…

@Darryl Ayo. I don’t think I can accused of weaselling out of talking about racism since I’ve written thousands of words and several essays on racism and the history comics dealing with a wide range of cartoonists running from Winsor McCay to Roy Crane to Will Eisner to George Herriman. I just don’t think Crumb’s work is racist, for reasons I’ve outlined.

“It’s scary to talk about racism if you are white, I know.” I’m not white.

@Nate. Well, its an open question as to whether Crumb’s satire is effective or not, and that’s worth debating. But we have to start from the premise that there is a satirical intent there. The unwillingness of Crumb’s hostile critics to see the satirical intent leads to problematic readings.

@Noah. Sigh. This is really a subject for a whole essay, not a blog post, but briefly: I’ve sketched out some of the history of blackface imagery in comics on TCJ.com (see here: http://www.tcj.com/racism-as-a-stylistic-choice-and-other-notes/ and here: http://www.tcj.com/black-readers-white-comics/ . The basic story is that blackface was pervasive from the beginning of comics till about the mid-1940s. At that point, thanks largely to pressure from civil rights groups who were able to argue in the context of World War II that such racist images were anti-American, newspaper syndicates started clamping down on blackface images. Thus Ebony White disappears from the Spirit in the late 1940s. An unfortunate side-effect of this otherwise wholly admirable development was that the cartoonists stopped drawing blacks in general. The comics sections (and to a lesser degree comic books) became whitewashed. Aside from Tarzan, there were few blacks in the comics of the 1950s and 1960s. Emblematic of this is the fact that there were no black kids in Peanuts from the start till 1968 when Franklin was introduced. So Crumb was working in a context where images like McCay’s Imp or Eisner’s Ebony White had disappeared for about 20 years and people weren’t even used to seeing blacks of any sort in the comics (except in jungle comics like Tarzan). That’s why Anglefood McSpade was so shocking, in addition to the fact that he threw in every conceivable racial stereotype and did so in curvy cute cartooning style (making the disjunction between the racism of the images and the style even more blatant). That’s why the character, and Crumb’s other racial cartoons of the period, have to be seen as having a satirical intent. They were salutary reminders of a racial history that was then in the process of being whitewashed from history.

It’s true that white supremacists sometimes appropriate Crumb’s comics. There’s aloso the case of the neo-Nazis reprinting his Swiftian stories “When the N—–s Take Over America” and “When the Goddamn Jews Take Over”. But in my experience racists and neo-Nazis aren’t very smart and are certainly not alive to irony and satire (which is one reason they are racists and neo-Nazis). Certainly the writers at Hooded Utilitarian should be capable of more complex critical responses than those formulated by the Arayan Brotherhood.

I don’t think you’re actually talking to Nate, Darryl, but…I just want to say that I don’t think he’s changing the subject to sexism from racism. I think his point is that Crumb’s misogyny and sexism are intertwined in the A M caricature…which I think is right. He’s not just parodying that caricature; he’s getting off on that caricature. And I think the getting off is about racial fetishization as well as gendered fetishization. All of which is…really problematic.

Jeet *is* willing to talk about racism in some contexts, like here.

Jeet: I really shouldn’t be talking to you since I really feel offended by what you said. Your arrogance and condescension are simply unacceptable in a civilized discussion.

Anyway, you base your assumptions in some newswpapers’ and comic books’ editors’ warning their artists against black stereotypes because of, let’s face it, economical reasons. Another matter altogether is what were the prevailing views of race in America in 1968. To know if Angelfood McSpade was offensive or not you need to ask the 1968 readers of _Zap_ comics # 2 if they felt offended. If your way of writing history is by guess work, I can see that you are a great historian (that’s irony, by the way)!

One more thing: images are polysemic and you are not the owner of meaning.

Still no answer to Trina! I’m patiently waiting!

[Edit: This is in response to Jeet’s last.]

The problem with racists is that they are racist, not that they are dumb. Racism is not an intellectual error. Lots of very smart people have been racist.

Your whole last paragraph is simply hand-waving. The issue isn’t whether people here or there are smart or dumb. The issue is, what is it about Crumb’s iconography that makes it so easy for racists to appropriate it? Presumably the point of his satire is to make racists uncomfortable; to show that racism and racist iconography is ridiculous and wrong. Instead, his iconography makes them happy, and they adopt it as their own. That seems like a failure of his art to me, Jeet. If his anti-racist art is giving aid and comfort to racists, in what sense is it an effective satire? And how does it mitigate their enjoyment of the material to tell them, “ha, ha, you’re dumb, you don’t get it!” It’s really not clear to me that you, with your smarts and your anti-racist credentials, are really getting anything like the last laugh there.

Your history of blackface is interesting, but I don’t think it necessarily does the work you’re hoping for in terms of defending Crumb. In some ways it does the opposite. If blackface was not especially prevalent, what exactly was the point of mocking it? If there were not many representations of blacks in comics, was the best anti-racist response to that a return to blackface imagery? Doesn’t that suggest a failure of imagination, whatever the satiric purpose may have been? And isn’t it a problem that on the Joplin cover, his reuse of the iconography is largely indistinguishable from earlier uses — that, whatever his intent, the result does little to distinguish itself from the source material?

You also haven’t responded at all to my suggestion that intensifying racist caricature does not undermine the caricature, no matter the intent of the creator. I’m actually curious to hear what you think about that.

Jeet…sorry, I just wanted to say a little bit more about your dismissal of the responses of racists to Crumb’s work.

I think it’s actually really important when critiquing racism, or talking about racism, to understand how racists think. Of course “racists” aren’t just neo-Nazis; racism is institutional and affects lots of people. But the point is, how racists (avowed and otherwise) react is what racism is. It’s what you’re talking about when you’re talking about racism. The fact that Crumb’s satires of racism so often misfire suggests to me that he doesn’t in fact understand very well how racism works and hasn’t managed to deal with racism effectively in his art.

Noah:

You seem to assume that Angelfood McSpade is satire. I continue to think that it is not. His later attempt with the Jews and black people taking over America, on the other hand…

Nate: “The gestures toward social critique and [fill in the blank] basically look like set dressing for a self-indulgent romp.”

For me, that pretty much sums up Crumb. I think he’s given way too much slack on oh-so-many levels. The notion that Crumb is a brilliant satirist is a fantasy dreamed up by his most ardent admirers.

Noah: “He’s not just parodying that caricature; he’s getting off on that caricature. And I think the getting off is about racial fetishization as well as gendered fetishization. All of which is…really problematic.”

Precisely. What Crumb did was masturbate publicly. He was an exhibitionist whose biggest turn-on seems to have been exposing all of his darkest fetishes and then watching the reaction. He didn’t even need to defend or rationalize his work, because there have always been fans like Jeet there to do it for him, contriving elaborate interpretations of The Maestro’s work, like geocentrists doggedly adding new epicycles and equants, determined to prove that the Earth really is the center of the universe. And if you dare to suggest that sometimes a horrific racial stereotype is just a horrific racial stereotype, they will ultimately resort, as Jeet has, to insulting your intelligence and imagination. Yada yada yada.

Happily, as “R. Crumb’s Heroes of Blues, Jazz and Country” demonstrates so well, Crumb himself seems to have moved on.

Crumb’s said it’s satire I think, more or less. I’ve seen him use the character in various places, but I haven’t read all the strips with her in them, so I’m giving him the benefit of the doubt.

I think this page for example…I don’t see how that’s not celebrating/fetishizing the stereotype, especially given Crumb’s general attitudes towards women. It doesn’t seem like a pointed statement against racism or blackface caricature. It is crude, but the crudity seems in the interest of titillation, not disgust (or of disgust as titillation, perhaps.)

I have to say, I get little enjoyment out of that strip either. It doesn’t seem funny or insightful or clever. It’s just a retailing of really vicious racism and misogyny, presented as a kind of horny chuckling fantasy. Do you really think that’s comparable to Swift, Jeet?

@Matt Thorn. “Precisely. What Crumb did was masturbate publicly. He was an exhibitionist whose biggest turn-on seems to have been exposing all of his darkest fetishes and then watching the reaction.” I think that’s true of some of Crumb’s work but by no means all, and I’d specifically don’t think that’s true of the Angelfood McSpade stuff because Crumb isn’t developing his own private iconography there but rather using visual tropes that were very common in American popular culture in the early 20th century. Why are people who try to engage with the actually complexity of Crumb’s racially charged strips – including grappling with the iconographic origins of his imagery – to be dismissed as fans, whereas people who have a one-dimensional knee-jerk reaction to that work (that it contains “horrific racial stereotype” and therefore should be dismissed outright, case closed) seen as astute critics? In general, the more nuanced and historically grounded reading is the more rewarding one. Even saying that “What Crumb did was masturbate publicly” (although partially accurate) seems too dismissive because its part of Crumb’s great achievement that he showed that it was possible for a cartoonist to put his raw id on the page, something that hadn’t really done before. That act of making cartooning an intensely private obsession aligned Crumb with the major tradition of modern art – the tradition of Lawrence, Joyce, Henry Miller, Piccaso, etc. As far as I know, no cartoonist before Crumb had taken on the mantle of candour that defines modern art. That’s why Crumb was such a revolutionary figure in the late sixties, influencing countless cartoonists in North America and Europe.

@Domingos Isabelinho. I think my general response — that I see Crumb’s work as a satire on racism rather than as racist art — does answer Trina Robbins’s objection. It’s true that “images are polysemic” but that actually undercuts your point, since the richer and more polysemic reading of Crumb’s work is that he’s satirizing racist images (which means that the images are reflexively engaged with the history of comics). By contrast, just saying the images are racist seems like a remarkably monosemic reading, the opposite of polysemic. I’m sorry that you found my response to your posting to be insulting but really my language was very mild compared to the usual discourse found in the Hooded Utilitarian (and on other sites where HU writers can be found). Noah, for example, has referred to Crumb as a “shithead.” That’s far harsher language than anything I’ve ever used. When Noah did that, I didn’t see you dismiss him for “arrogance and condescension” that is “simply unacceptable in a civilized discussion.”

@Noah. I’m not sure how to answer this since my reaction to the Angelfood McSpade strip you linked to is the opposite of yours. I think it is 1) hilarious and 2) a very puissant satire that takes standard figure from Western mythology (the hyper-sexualized African native, as seen in National Geographics and countless jungle pulps) and presents this stereotype in such an absurd and over-the-top manner that its very ridiculousness is impossible to ignore. Is it the equal to Swift? Well, no (because such comparisons are absurd given the difference of eras and genres), but it is Swiftian. “Racism is not an intellectual error. Lots of very smart people have been racist.” Well, let me modify my position and say that racists, at least in my experience, however smart they might otherwise be, aren’t alive to satire and irony. At best, they can understand sarcasm but not more refined types of humour, especially those that involve a measure of self-awareness. So it doesn’t surprise me that racists don’t understand the point of Crumbs work. “If blackface was not especially prevalent, what exactly was the point of mocking it?” Crumb’s work was a comment on the way blacface had been suppressed which led to a more general whitewashing of comics. To put it another way, the comic strips of the 1920s were much more racist than the comics of the 1950s and 1960s, but in the 1920s there were many black characters (and Jewish characters and Italian characters and characters from many races and ethnicities). By the 1950s and 1960s, almost everyone in comics was generically white. Crumb’s revival of blackface was a comment on that situation, the whitewashing of American culture which was the ironic side-effect of a genuine move to social progress. That’s the historical complexity that Crumb was addressing which his hostile critics aren’t willing to consider.

Noah: in that story, as I say above, she’s an allegory for marijuana or LSD or whatever… (It’s the same thing as the meatballs in another story.) But this reading doesn’t invalidate what you say. On the contrary: the wench is seen as naive and willing to serve uptight white executives, and savage… it’s like a sexual counterpart to Al Capp’s shmoos. Maybe I’ll stumble on Angelfood again next month, who knows?…

In the IJOCA Vol. 12 No. 2/3 there are two great essays about these topics in Eisner’s and Yolanda Vargas’ and Walt Kelly’s comics. I highly recommend them (especially the last one).

The arguments wandering a bit here so let’s try and rephrase this one a more fundamental level.

As I understand it, what Noah Berlatsky and Domingos Isabelinho are saying is this: that there is no difference between Winsor McCay drawing the Jungle Imp in 1906 and Robert Crumb drawing Angelfood McSpade in 1969. Both are “horrific racial stereotype” (to use Matt Thorn’s words).

My argument is that there are huge differences in the contexts out of which these images emerged and that because of these different contexts they have to be interpreted differently. The different contexts include 1) the historical changes from 1906 to 1969 2) the pervasiveness of the blackface image in 1906 as against the way it had become taboo in 1969 3) the differences between a newspaper comic aimed at a general “family” audience and a sexually charged underground comic book that was aimed, explicitly, at an adult audience and 4) the intent (as far as we can know it) of the artists. Because of all these differences in contexts, I’m pretty confident in saying that McCay’s Jungle Imp was a racist stereotype and Crumb’s Angelfood McSpade was a satire on racism.

What I find puzzling is the argument that historical context doesn’t matter.

Jeet:

How can *one* opinion, whatever it is, be polysemic? It’s my reading and your reading and other peoples’ readings that proves that the image is polysemic and no one is the owner of the right reading.

And no, you haven’t addressed any of Trina’s objections. To Trina if it is satire or not isn’t the point. The point is that such imagery may hurt people. Let me remind you: “depicting black people as gorillas isn’t funny. Maybe one way of thinking of it is, if it hurts people it shouldn’t be simply dismissed as harmless parody.”

Jeet:

I’m baffled! Are you serious? How can you misread with such accuracy? You’re a master misreader, let me tell you!…

Um, hey, I didn’t realize that my comment would result in my mailbox getting flooded with never-ending commentary, some of it from a person who has no business on any civilized blog. I think I’m accustomed to more genteel commentary. May I be excused, please? Is there a way of removing me?

Thank you.

I have never seen Angelfood McSpade described as a legitimate satire or social commentary. EVER. This is is literally the first time that has ever been suggested in my presence.

That can be YOUR read, but as a black person who grew up highly cognizant of this imagery, I don’t see it, disagree that it’s there, and if it IS there, it’s not smart enough commentary to speak to me.

I maintain that Crumb’s blackface strips such as the Angelfood are racist AND bullshit. Just as hostile and repugnant as his general violence against women.

You need to come harder to the table if you’re going to convince anybody. I’m hardly deaf to satire. It just looks like you’re making stuff up.

“I’d specifically don’t think that’s true of the Angelfood McSpade stuff because Crumb isn’t developing his own private iconography there but rather using visual tropes that were very common in American popular culture in the early 20th century.”

Don’t have time to go into this all…but I think this is really confused, Jeet, and perhaps at the root of some of our differences. If you’re drawing a bright line between private iconography and visual tropes, I think you’re very much missing what Crumb is doing. He’s (personally) fetishizing the public tropes. That is, the tropes of racism are treated as nostalgic and as fetish objects. This is not at all unusual. Indeed, visual tropes have power because they click with individuals. You appear to think that because Crumb is using tropes that were no longer in vogue, he must be satirically commenting on them — he must not be invested in them. But that’s not the only option. He could be nostalgic for them. He could think they’re funny and worth reviving. He could find them titillating. He could think it’s cool to shock the squares by indulging in racism. I think all of these are in fact present, as well as (perhaps) satire.

History is useful, but history isn’t theory. You’ve assuming that anyone taking history into account has to come to the conclusions you do. That simply isn’t the case. Nobody is saying the historical context doesn’t matter. People are saying that the historical context doesn’t absolve Crumb in the way you want it to.

Exactly. I also think that there is satire in the Angelfood McSpade story, but it’s Crumb’s usual satire of the uptight white man. Not of the white man’s racism.

Ha! The “shithead” thing — you’ve brought that up multiple times! It’s herein case people want to see it.

I can’t take it back; I think that Cheap Thrills cover is heinous, and calling Crumb a shithead for that is pretty mild. Which isn’t to say he hasn’t done worthwhile work in other contexts, or that he’s a shithead always.

Anyway…I have to say, the idea that Crumb is particularly critiquing the disappearance of black figures in comics strips seems kind of nutty to me. Maybe there’s an interview or something where he says that, but it just seems like a stretch. I can certainly see a reading where he’s satirizing the imagery itself, but where do you see in the work a critique of absence, or a concern with the under-representation of black people in media?

You’re comments on racists failing to get Crumb don’t really address any of my points. If Crumb’s point is anti-racist, the fact that he has been embraced by racists is a problem for his art. Claiming that it’s the racists’ fault for lack of irony or subtlety just seems like a case of blaming the victors. You laugh at them for being dumb and they laugh at you for not recognizing a racist image when it’s put in front of your nose. Why does that make you smarter than them exactly?

As for finding that A.S. strip hilarious or Swiftian…it just seems really dumb and obvious to me. And…if you’re willing to see the sexism in Crumb’s work, how do you separate that particular strip from the sexism exactly? I mean, it seems like a big part of the point there is the fusing of racist iconography with his own particular sexual fetishes; he’s using the racist iconography the better to turn a woman into an animalistic thing; a hypersexualized body. Or is the racial satire so brilliant it negates the sexism in your opinion? So Crumb’s only being sexist when he objectifies white women?

Drat, Trina; I’m sorry. I’m not actually positive how to remove you…I will ask for help though. Apologies again.

::So Crumb’s only being sexist when he objectifies white women?::

Cough cough. Nice shot, Noah.

In one sentence, wraps up what usually disturbs me about the majority of commentaries about Crumb and his work. Particularly the appreciative commentary.

And I insist that I don’t want to take Crumb away from people. I just think that it’s a severe mistake to hand-wave his more extreme indulgences. These are conversations that many people interested in Crumb are afraid to have for whatever reasons.

You use racially charged imagery, prepare to be challenged. You discuss racially volatile work, prepare to listen to people being represented by that work and be prepare to be wrong.

Daryl,

In case I wasn’t clear, and, like Noah, I’m not sure you were including me in your statement, I did not mean to suggest that the strip doesn’t come off as racist. Quite the opposite, it comes off as racist because it’s sexist, which given the long history of white gaze/black body, makes it doubly problematic.

@Domingos Isabelinho. “The point is that such imagery may hurt people.” The idea that artists should refrain from making images (or more broadly art) because they might hurt people is a really dangerously illiberal one because almost art of any potency has the power to offend. Famously, some Christians have been offended by images of Christ (going back to at least the iconoclasts of the middle ages to Savonarola’s bonfire of the vanity to the Protestant iconoclasts to those offended by The Passion of the Christ). And there is a long history of some Muslims being offended by images of Mohammed, a history that predates the controversy over the Danish cartoons. If you look at books that get challenged or censored in school libraries, you’ll see how art much milder than Crumb causes offense and hurt. Not just Twain’s Huckleberry Finn (for the n-word) but even Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird (which has been at times declared objectionable to white readers because of its portrayal of racism), the various works of James Baldwin (also objectionable to whites who don’t want to think about racism), and William Steig’s Sylvester and the Magic Pebble (offensive to police because it portrays them, literally, as pigs – a similar compliant to those who object to the portrayal of Poles in Maus). For that matter, I’ve heard men take offence at the brilliant science fiction satires of the late Joanna Russ and Israeli nationalists take offence at Joe Sacco’s Palestine. And since Swift’s name has come up a couple of times, it is worth recalling that he published almost all his satires (including A Modest Proposal and Gulliver’s Travels) anonymously, because they hurt the feelings of all sorts of groups, including both the English and the Irish. If we really wanted to avoid hurting people’s feelings the simplest solution might be to ban the production of all art outright.

“I also think that there is satire in the Angelfood McSpade story, but it’s Crumb’s usual satire of the uptight white man. Not of the white man’s racism.” This is half-true: the satire of the uptight white man is part of the satire of racism. It’s because the deeby white man is so sexually repressed that he fantasizes about the supposedly natural and untamed body of Angelfood McSpade.

@Darryl Ayo says: “I have never seen Angelfood McSpade described as a legitimate satire or social commentary. EVER.” Um, there is a long history of people talking about Crumb as a satirist and his racial work as satire (Matt Thorn alluded to this fact in his post). R. Fiore, for example, had a good article about this in the Comics Journal at the time of the Crumb documentary. The arguments I’m making aren’t novel to me.

“You use racially charged imagery, prepare to be challenged.” I agree that Crumb’s use of racially charged imagery should be discussed and challenged. I just happen to find most of the discussions here one-dimensional and simple-mind, largely because they ignore the evident (and even blatant and heavy-handed) satiric intent of the art and also the historical context out of which it emerged. By all means, let’s talk about these images, but let’s not do so in a reductive way.

“You discuss racially volatile work, prepare to listen to people being represented by that work and be prepare to be wrong.” I’m not sure if there is a “right” or “wrong” interpretation to any really complicated work of art. Such art is always, to use Domingos Isabelinho word, “polysemic” – i.e. open to different and radically conflicting interpretations. I happen to prefer interpretations that are historically-grounded and that engage with the complexity of the art but I obviously such material will always be polorizing. What’s troubling about this debate is that people seem to want to foreclose debate by simply saying these images are racist and there is nothing more to be said about them. But there is in fact much to be said about them.

@ Noah Berlatsky says: “If you’re drawing a bright line between private iconography and visual tropes, I think you’re very much missing what Crumb is doing. He’s (personally) fetishizing the public tropes. That is, the tropes of racism are treated as nostalgic and as fetish objects. This is not at all unusual. Indeed, visual tropes have power because they click with individuals. You appear to think that because Crumb is using tropes that were no longer in vogue, he must be satirically commenting on them — he must not be invested in them. But that’s not the only option. He could be nostalgic for them. He could think they’re funny and worth reviving. He could find them titillating. He could think it’s cool to shock the squares by indulging in racism. I think all of these are in fact present, as well as (perhaps) satire.” Again, half-true, half-true. The fact that Crumb implicates himself (and his own nostalgia and fetishes) in his critique of racism makes that critique more potent, not less. It is easy enough to denounce racism in others (see the collected writings of N. Berlatsky); what’s harder is to examine the racist impulses in your own brain. Collecting old blues records, for example, is clearly important to Crumb but he’s never shied away from looking at the exploitive or pathetic aspect of anaemic and dorky white guys trying to find “authenticity” in the vibrant culture of long-dead black artists. For me, Crumb’s reflexive and self-aware explorations of racism are part of his greatness as an artist. It’s hard for me to think of another white artist who has really mapped out with such radical thoroughness all the crazy ideas that white people have about blacks (and other non-white races). I would think much less of Crumb as an artist if he had never touched the subject of race.

“If Crumb’s point is anti-racist, the fact that he has been embraced by racists is a problem for his art. Claiming that it’s the racists’ fault for lack of irony or subtlety just seems like a case of blaming the victors” Um, have you actually read “When the Goddamn Jews Take Over”? (Probably not, since you have a habit of talking about comics you haven’t read). It ends with white Christians blowing up the planet in a nuclear holocaust in order to prevent the horrors of Jewish domination. The fact that white supremacists have celebrated this comic strip – which shows that the logical outcome of their thinking is the destruction of all humanity – is a pretty searing indictment of racism. It shows exactly how bonkers these people are. In that sense, Crumb has one-upped even Swift: its as if the English started taking “A Modest Proposal” seriously and started making cookbooks for how to roast Irish babies.

“If you’re willing to see the sexism in Crumb’s work, how do you separate that particular strip from the sexism exactly?” The sexualization of Angelfood McSpade makes narrative sense because these ooga-booga images of African “native” women are often been sexualized (not just in comics but also in the more genteel anthropological precincts of National Geographics magazine). The violent sexualization of women in the other works feels very different because Crumb isn’t referring back to a shared visual vocabulary but rather is coming up with intense and novel ways to express revulsion (I think the bird-women strips are a good example of this). The focus of the Angelfood McSpade story is how messed up white attitudes to race and sex are (and how fused they are). The focus of the bird-women strips is how scary powerful women are (although also, Crumb being Crumb, how sexually fascinating they are).

To clarify a point: Savonarola didn’t burn images of Christ but rather other types of art that he found immoral. But the point stands: people can be offended by art of all sorts.

In Crumb’s case it’s because there IS nothing more to be said about the images. You’ve made your case, but I don’t believe you. I’m not some mealy mouthed, spineless liberal who wrings his hands and pats his brow all day. I appreciate work that uses racially charged ideas to CHALLENGE racism. But I’m telling you, you’re too in love. That is not the case with Crumb. He’s a bonafide racist.

I don’t know how they do it on your block, but where I’m from, people can TELL when they are being mocked and derided. I don’t need to second-guess an insult. If there was a satire there, perhaps it’s the kind that only white folks get. Which is pointless.

Again, I’m not personally offended by Crumb. But his work is offensIVE. And if the prime argument is that Crumb is using this imagery to speak a point about white people’s consumerism or consumption or whatever the point–THEN MORE IS THE SHAME.

Black people are not objects. We are not accents or punctuations in the conversations of white people. We are not symbols here to teach anybody else a lesson. We are also NOT STUPID.

@ Darryl Ayo. I’m tempted to give you the last word since we’re just going to keep repeating ourselves and we’ve both made our points of view clear. And in fact I think I’ll make this my last post but I wanted to emphasize once again that I think dismissing Crumb’s work is a mistake for those of us who struggle to fight racism (which I try to do in my work as a historian and journalist).

Racism has all sorts of dimensions: political, social, economic. But one major reason why racism is a powerful force in the world because it is based on twisted psychological and sexual feelings. For me, the value of Crumb’s incendiary racial strips is that they really explore in a deep and persuasive way the psycho-sexual dimensions of racism, the way racists both fear blacks and desire/envy black bodies. The point might seem obvious but Crumb really has, through his unparallel drawing skills, made it so blatantly obvious that it is impossible to ignore.

I don’t think we can fight racism without understanding how racists think (and it is often thinking of a very twisted kind). Because Crumb has delved deeper into the psychology of racism than virtually anyone I know (at least in the comics world but I can’t think of too many others in art and literature that come close), I find his work really valuable. The struggle against racism would be diminished if, out of a too-quick disgust at shocking images, we refuse to learn from Crumb’s work. And I’m not writing as an uncritical fan of Crumb’s work because I actually think his large oeuvre is very uneven, and there is much in there to criticize.

“The violent sexualization of women in the other works feels very different because Crumb isn’t referring back to a shared visual vocabulary but rather is coming up with intense and novel ways to express revulsion (I think the bird-women strips are a good example of this). The focus of the Angelfood McSpade story is how messed up white attitudes to race and sex are (and how fused they are). The focus of the bird-women strips is how scary powerful women are (although also, Crumb being Crumb, how sexually fascinating they are).”

Again, you seem to think that because Crumb is using racist imagery that others have used first, he can’t himself find the imagery exciting or provocative or fun. The A.M. imagery is about the exciting animality of women. You say it’s different from other Crumb imagery because it’s not as personal. But Crumb’s obsession with the titillation of blackness is a very personal aspect of his work. It just so happens that it’s a personal aspect of his work that’s a commonplace kink in our society rather than a more idiosyncratic one. That seems to me to make him more culpable if anything, not less.

Given your analysis, it’s not really clear how it would be possible for Crumb to create a sexist strip focusing on black women. If it’s white women, it’s personal animus; if it’s black women, he’s brilliantly deconstructing the connection between race and sexuality. It really seems like a double standard.

The argument that it’s all Crumb self-reflexively critiquing his own problems with race and sex seems like a cop out to me too. Why couldn’t he just be reveling in them? How would that look any different? I think there is in his work at times a measure of self-critique…but I think there’s also an excitement or a boasting about his willingness to make these things public and tell it like it really is. Indulging in racist imagery becomes a sign of his freedom from the kind of uptight whiteness he portrays in the strip. He’s not just criticizing the white men for wanting A.M.; he’s criticizing them for not having her; for not being as kinky and funky and open as Crumb himself.

I mean, I agree (I don’t think I’ve ever disagreed?) that Crumb’s investment in these issues is complicated — but one of the reasons it’s really complicated is because it’s far from clear that his anti-racism (which you admit) wins out over his racism (which you also kind of admit to, right? There must be racism there if he’s critiquing his own racism.) The question isn’t whose reading is more complex; the question is what the balance of those two things are. You’re claim that reasonable people can’t even dare to suggest that the racism might win out seems odd to me.

I haven’t read “When the Goddamn Jews Take Over” — but genocidal fantasies, even annihilating the human race to protect it from infection, are hardly an intensification or brilliant critique of racism. That’s just racism; it’s not at all odd to me that racists would find that congenial. If it’s odd to you, or if you think it really undermines the logic of racism, I can only conclude that you don’t have a very clear understanding of how racism works — which seems of a piece with your claim that Crumb is our greatest analyst of racism.

Again, Crumb’s satirical tactic when he’s satirical is intensification, and intensification doesn’t work very well with racism, which can’t be undercut by intensification. You need to find a way to go outside of or rework the metaphors (as Swift does, turning racism into cannabalism) or you risk being coopted.

Sigh. I wasn’t going to comment more but since you’ve asked some questions here goes: “Given your analysis, it’s not really clear how it would be possible for Crumb to create a sexist strip focusing on black women. If it’s white women, it’s personal animus; if it’s black women, he’s brilliantly deconstructing the connection between race and sexuality. It really seems like a double standard.” No, I think if Crumb had done something like the bird-women strip with black women – i.e. a strip whose dominant tone is a kind of paranoid animosity towards black women, shown to be demented harpies – then such a strip would be both racist and sexist. But the tone and narrative of Angelfood McSpade is very different.

“I mean, I agree (I don’t think I’ve ever disagreed?) that Crumb’s investment in these issues is complicated — but one of the reasons it’s really complicated is because it’s far from clear that his anti-racism (which you admit) wins out over his racism (which you also kind of admit to, right? There must be racism there if he’s critiquing his own racism.)” Its odd to me to talk about anti-racism and racism in Crumb’s in terms of “admit to” – as if this were a criminal trial rather than a discussion about art. Crumb, like every other white person of his generation, grew up in a racist culture. In an interview Crumb talks about an experience he had as a teenager bringing a black friend to his home and then being shocked when his grandmother started berating the friend with the n-word. Every white anti-racist of Crumb’s generation – aside maybe from a few kids who grew up in very radical households — is also a recovering racist or former racist. Which is another way of saying that in psychological and personal terms you can’t so easily demarcate the difference between racism and anti-racism. Becoming an anti-racist is a process, rather than a matter of signing up to an agreed upon party-line.

Crumb’s way of grappling with his racist cultural background was historical in nature: he returned to the iconography of his grandmother’s generation (the early 20th century) and revived it so that it was possible to see a connection between the blatant racism of the past and the more latent (but still pervasive and powerful) racism of the present. That might not be an artistic strategy you like or find rewarding, but it is one way to deal with these issues.

Swift is probably a much greater figure (although as always I don’t think these types of comparisons make sense. But there is also something cold and cerebral about Swift: he distances himself from the evils he denounces (as I mentioned above, he very rarely signed his name to any of his satires, including A Tale of the Tub, Gulliver’s Travels and A Modest Proposal). By contrast, I very much admire the way Crumb implicates himself in his critique of racism. And he always signs his name to his work. (Of course, there is also the difference of eras: the 18th century was a time of masks and personas whereas Crumb lives in a period that celebrates autobiography and tell-all confessions).

I’m glad to see, finally, Jeet siding with the racists. Are black people offended by Crumb’s racist imagery? Tough titty!… Crumb’s an ahtiist, a genius who can do whatever he pleases!… Plus: there’s no difference at all between a black person offended by Angelfood McSpade and Muslims wanting to kill Kurt Westergaard. Besides, your reading skills continue stellar, no doubt about it. Here’s what I wrote (and I quote myself): “I’m not denying Robert Crumb or any other artist, for that matter, the right to draw “anything [s/he/they] want[.]”

Unfortunately I’ve been here many many times (it’s pretty much the story of my relationship with comics fandom, as a matter of fact). Fanatics (I’m not kidding, they call themselves “fans”) saying that I’m too dogmatic because I attack their sacred cows. Strangely enough they’re not too dogmatic in return because they defend the herd with claws and teeth.

White people are too sexually repressed? The only thing that they have to do is go to the jungle where there’s this yummy apelike wench gladly waiting for them. Jeez! If you don’t see that as offensive I would like to see what you do find offensive. I’m sure that it is quite a sight to behold!

Jeet:

“Crumb’s way of grappling with his racist cultural background was historical in nature: he returned to the iconography of his grandmother’s generation (the early 20th century) and revived it[…]”

Yup, that’s camp.

“[…]so that it was possible to see a connection between the blatant racism of the past and the more latent (but still pervasive and powerful) racism of the present.”

No, that’s what you say. That’s your interpretation. I, for one, don’t see it at all.

@Domingos Isabelinho. I realize you wrote “I’m not denying Robert Crumb or any other artist, for that matter, the right to draw ‘anything [s/he/they] want,'” but this principal seems to be in tension (to say the least) with the idea that artists should be careful not to hurt people’s feelings. I was being ironic (in a Swiftian way) when I wrote: “If we really wanted to avoid hurting people’s feelings the simplest solution might be to ban the production of all art outright.”

If you find the Muslim example too far off, where do you stand on Huckleberry Finn. There have been plenty of people (both black and white, actually) who have taken offence at that book. Should we also be prepared to condemn Twain along with Crumb? The idea that the production and criticism of art should take into account hurt feelings and potential offensiveness is really very odd and unworkable. If Crumb’s work is racist, it should be condemned as racist even if it hurts no one’s feelings. But as I said before, it’s an open question as to whether the work is racist or not.

I didn’t say Crumb should get a free pass because he’s “an ahtiist, a genius who can do whatever he please!” I said that his allegedly racist work is in fact a very valuable satire on racism.

To say that I’m siding with the racists because I don’t find arguments from hurt feelings or offensiveness convincing is like saying that you are siding with the European far right when you so airily dismiss the concerns of Muslims over the Danish cartoons. This is a very loose type of “guilt by association” and not very convincing. Also, in the context of a discussion of racism, it’s a not a good idea to lump in all Muslims who objected to those cartoons with the minority of fanatics who want wanting “to kill Kurt Westergaard.”

The idea that sexual repression goes hand in hand with eroticizing the exotic (in a racially charged way) makes perfect sense to me. I’m not sure why you find it so odd. I suppose there is the question of to what degree Crumb is indulging in the fantasy of white man rather than just exploring it, but I’m not sure if that’s the best question to ask since, as I indicated above, Crumb’s value comes from his acute portrayal of the psychology of racism and his willingness to implicate himself in the fantasies he portrays.

@Domingos Isabelinho. No, the camp label doesn’t work at all. I can’t think of another work of camp that has the power to disturb or challenge the way Crumb’s racial strips do. Camp implies something that is colder and less unsettling.

I agree with Domingos here, as I guess I’ve said. I think the use of camp to describe what Crumb’s doing is really interesting; I hadn’t thought of it in that context exactly, but it makes a lot of sense. It also kind of fits into what might be seen as Crumb’s queer sexuality….

I do see where you’re coming from too, Jeet. I don’t find it as convincing (and I think your effort to separate the racism and sexism in A.M. is extremely strained), but it’s not a crazy interpretation or anything. I think there are elements of anti-racism and satire in Crumb’s work, or, at least, I can see that reading.

So…truce?

Sure, a truce is fine.

On “camp”. it might help me if Domingos can clarify what he means by camp. I keep picturing the items Susan Sontag discussed in her famous essay, and Crumb seem incongruous.

It’s somewhat weird to think of him as camp, because his queer sexuality (if you can call it that) is really very much a straight male sexuality too.

But…something like Twin Peaks, which I’ve just been watching is absolutely camp, and is pretty thoroughly disturbing and outrageous. So is much of Jack Hill’s work. I don’t think the outrageous imagery necessarily is a bar to camp at all (whether or not one agrees that Crumb’s imagery is effectively satirical or not.)

Jeet:

“No, the camp label doesn’t work at all. I can’t think of another work of camp that has the power to disturb or challenge the way Crumb’s racial strips do. Camp implies something that is colder and less unsettling.”

It’s unsettling to you, maybe not to Crumb’s readers in 1968. I don’t know for sure what they thought because I didn’t ask them, but you don’t know either, do you? It’s funny how you accuse others of being ahistorical when you do a retro reading using today’s values. But you’re an expert seeing specks on other people’s eyes while failing to see trunks in your own eyes, aren’t you?

And don’t expect me to give you a free lesson on camp. It would be a lesson from an incompetent person, anyway…

On the Jyllands Posten cartoons. As I said in my post: I’m not denying Robert Crumb or any other artist, for that matter, the right to draw “anything [s/he/they] want,” but drawings have consequences. In this case 140 people died because of the damn things. I guess that those drawings aren’t worth even one of those lives.

@Domingos Isabelinho “It’s unsettling to you, maybe not to Crumb’s readers in 1968. I don’t know for sure what they thought because I didn’t ask them, but you don’t know either, do you?” Well, it is possible to figure out, however incompletely, what some of Crumb’s original readers thought because we have articles about Crumb and interviews with other cartoonists, pretty much dating to the publication of the first Zap comics. From these sources, we know that Crumb’s use of blackface images were controversial right from the start — people were challenging him on it from early on. So I’m pretty confident in saying that these images, which are unsettling now, were also unsettling in 1968 and not experienced as reassuring, happy nostalgia.

Like all other forms of historical scholarship, this can be debated, but the debate has to take place on the field of evidence, not on surmises about what might have happened.

@Domingos Isabelinho. “And don’t expect me to give you a free lesson on camp. It would be a lesson from an incompetent person, anyway…” I don’t think you are an incompetent critic; I just think that you often make very abrupt judgements about works that would benefit from being expanded upon or clarified. In this case, if I knew what you thought camp means or other examples of works you consider camp, I’d have a better sense of why you think Crumb is camp. It’s an intriguing concept — and it fits nicely with the historical period Crumb emerged from, when camp was first being theorized — but it would help to have a more fleshed out account of camp. I do think that S. Clay Wilson’s work — particularly the pirate strips — overlaps with camp.

Am I supposed to believe in you? You give no primary sources whatsoever. Besides, some vocal critics are hardly the totality of _Zap_ comics # 2’s readers. According to Robert Beerbohm the print run was 20.000, but I don’t know how many items were actually sold.

Who’s doing abrupt judgments, now?…

I’d like to express my solidarity with Daryl Ayo and Domingos Isabelinho. I have been there. For some reason, Crumb’s fans feel more strongly about him than any other fans of cartoonists, will defend him to the death and find all sorts of excuses for what he draws and says. To them, he is god, and woe to those of us who dare criticize him. I have been on the receiving end of a lot of hatred and anger by fans who do not understand that the First Amendment gives me the right to criticize. I’m happy to see that I am not alone in my feelings. That said, I really would like to be removed from this list. At this point I feel we are beating a dead horse, and the comments are boiling down to “Is not,” “Is so.”

Thanks, Trina!

Two final comments:

1) Alan Dunn created a fine book; if you never read it it’s worth your scheckels, that’s for sure (try Abebooks);

2) Wait for Angelfood McSpade part II in a month or so. Since she stole this columns comments it seems to me that she deserves her own post.

@Domingos Isabelinho says: “Am I supposed to believe in you? You give no primary sources whatsoever. Besides, some vocal critics are hardly the totality of _Zap_ comics # 2?s readers.” This is an excellent argument against doing reader-response analysis (since the written response to any work is always a minority opinion) and indeed against any sort of historical research into public opinion. But the fact is that all historical scholarship relies on imperfect evidence but we have to make use of what sources exist. What do we find if we look at the printed responses to Crumb (there is a fine listing of them in the R. Crumb checklist that was assembled by Donald Fiene many years ago, and I would also suggest reading Patrick Rosenkranz’s Rebel Visions: The Underground Comix Revolution 1963-1975 and Mark James Estren’s A History of Underground Comics)? Well, Crumb has been controversial since nearly his earliest published work with some readers decrying the alleged racism of the work which other readers claim is satirical in intent. So basically the same argument we’ve been having here has been going on for 40 years. Both groups find Angelfood McSpade unsettling but they draw different conclusions from their response to the character. Are there readers who didn’t find Angelfood McSpade unsettling? Maybe such readers exist but I haven’t seen any evidence of that from the written sources, which are the only sources we have. Again, I prefer to debate this on the field of evidence, not on the field of surmise (acknowledging of course, the imperfections of the evidence.)

I must say, I find it dispiriting that any attempt to a have an intelligent discussion of Crumb’s work is dismissed as fannish special pleading. When people try to grapple with the difficult work of a Joyce, a Flannery O’Connor, a Piccaso or a Balthus they aren’t talked about as fans but rather as critics or analysts. The idea that the only people who can see merit in Crumbs work are fans is an attempt to keep comics in a cultural ghetto. It’s a foolish attempt since Crumb now has an audience that is far larger than the comics ghetto (an audience found in the world of galleries, museums and mainstream publishers). To pretend that Crumb only belongs to the world of comics is to ignore the major changes in the audience for his work that has occurred in recent decades.

I can understand people not liking Crumb’s work – it is thorny and abrasive. What I can’t understand is the anachronistic idea that his audience still consists largely of comics fans.

I suppose we should call a close to this argument and wait for Domingos Isabelinho next magnum opus on Angelfood McSpade.

Not that this proves anything in particular, but I think it’s worth noting that the racist website I found which was using Crumb imagery didn’t find it offensive or prickly or difficult. On the contrary.